0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

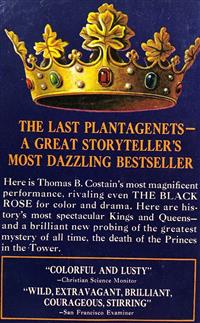

Thomas B. Costain's four-volume history of the Plantagenets begins with THE CONQUERING FAMILY and the conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066, closing with the reign of John in 1216.

The troubled period after the Norman Conquest, when the foundations of government were hammered out between monarch and people, comes to life through Costain's storytelling skill and historical imagination.

"Brilliant, swift-moving, full of action, rich in color." (B-O-M-C News)

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Conquering Family

by Thomas B. Costain

First published in 1949

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

The Conquering Family

by

Thomas B. Costain

AN EXPLANATION

I BEGAN these books of English history with the hope of carrying the series forward, under the general title of The Pageant of England to a much later period than the last of the Plantagenet kings. Pressure of other work made it impossible, however, to produce them at the gait I had hoped to achieve. And now the factor of time has intruded itself also. Realizing that my earlier objective cannot be reached, I have decided to conclude with the death of Richard III and to change the covering title to A History of the Plantagenets.

This has made necessary some revision in getting the four volumes ready for publication. The first five chapters in the initial book, which began with the Norman Conquest and covered the reigns of William the Conqueror, William (Rufus) the Second, and Henry the First, had to be dropped. The first volume in this complete edition of the four begins with the final scenes in the reign of Henry the First whose daughter married Geoffrey of Anjou and whose son succeeded in due course to the throne of England as Henry the Second, thus beginning the brilliant Plantagenet dynasty. The title of the first volume has been changed to The Conquering Family. In addition to the deletion of the early chapters, a few slight cuts and minor revisions have been made throughout the series. Otherwise the four books are the same as those published separately under the titles, The Conquerors, The Magnificent Century, The Three Edwards, and The Last Plantagenets.

THOMAS B. COSTAIN

CHAPTER I

Where the Planta Genesta Grows

THE Angevin country begins between Normandy and Brittany and continues down through Maine and Anjou. In the Middle Ages this fair and romantic land was dotted with towns and castles of great interest and importance. Here were the castles of Chinon, stretching like a walled city along a high ridge, here was Angers with its many-towered and impregnable castle, here also the famed abbey of Fontevrault where many great figures of English history are buried. Here in the spring and early summer the hedges and fields were yellow with a species of gorse (it still grows in profusion) called the planta genesta. It was in an early year of the twelfth century that a handsome young man named Geoffrey, son of the Count of Anjou, fell into the habit of wearing a sprig of the yellow bloom in his helmet. This may be called the first stage in the history of the conquering family who came to govern England, and who are called the Plantagenets.

The Angevin country had been ruled through the Dark Ages by a turbulent, ambitious, violent, and brave family. Strange stories are told about these ancestors of the English kings. The men were warriors who held the belief that forgiveness could be bought for all their wicked deeds, with the result that they were active Crusaders (one of them becoming King of Jerusalem) and they donated many beautiful chapels and shrines to the Church. Some of the women were quite as violent as their husbands but all of them seem to have been beautiful. There was, for example, the forest maiden Melusine who married Raymond de Lusignan, the head of one of the great Angevin families, after getting his promise that he would never see her on Saturdays. It was a happy marriage until the husband’s curiosity led him to hide himself in her boudoir. He found then, to his horror, that from the waist down she had taken on the form of a blue and white serpent. The wife died as a result of this revelation but her spirit continued to haunt the Lusignan castle, causing much fear by the sound of her swishing tail. There was another called the witch-countess who was forced to go to mass by four of her husband’s knights and who vanished into thin air at the Consecration, leaving them all holding corners of her outer robe, from which came a strong odor of brimstone. Finally there was Bertrade, the supremely beautiful but disdainfully wicked countess who ran away to live with the French king in what was called, even in those dissolute days, a life of sin.

The Counts of Anjou and their lovely but wicked wives gained such an unsavory reputation over the centuries that the people of England were appalled when they found that one of them was to become King of England. This was young Henry, the grandson of England’s Henry I and of the Count of Anjou, and there was much angry muttering and shaking of heads. But the half of young Henry which was English predominated over the half which was Angevin. He proved a strong and able king and, although some who followed him displayed more of the wild and picturesque half of their blood inheritance, the days of their rule in England were fruitful and spectacular. The men were kingly and their women were lovely. They created an empire and they fought long and terrible wars and enriched the island with the booty they brought back. The English people were so proud of them that they often forgave their wickednesses and their peccadilloes.

2

It was low country, much of it lying in the valley of the imposing Loire, and the land was fertile. It followed that the natives devoted themselves largely to agriculture. They raised crops of wheat and rye and oats, and on all the little streams running in all directions the stones of the millers ground out fine flour. The fields where the planta genesta grew were good for pasture, and the cattle which browsed there were fat and the horses had good bones and glossy coats. The knights of France depended much on the Angevin fields for the chargers they rode into battle. Some vineyards covered the hillsides and excellent light wines were produced.

While the nobility wrangled and fought and led forays into each other’s territory, and committed all manner of barbarities, the stolid peasants went on plowing their land and tending their stock, and paid as little attention as possible to the menacing activities of the gentry. Ironically enough, it was not until the Counts of Anjou removed themselves to England to reign there as the Plantagenets that the stout peasantry found their land torn by family strife and the march of conquering armies.

In the Angevin provinces of France today there is little memory left of those stirring days. The name Plantagenet does not stir any recognition, although a nod can sometimes be won with the mention of Richard Coeur-de-Lion. The long stretch of Chinon’s walls is still to be seen and it is sometimes possible to find a guide who will lead the way to a spot in a tiny chapel where great Henry II died. The merest glimpse may be had because of the ruined walls and the high weeds, in which might lurk serpents with blue and white tails. Mirabeau is a rather quiet town with nothing left of the castle where that wise old harridan, Eleanor of Aquitaine, held out against Arthur and his Breton forces until her blackavised and black-hearted son John came to her rescue. It was at Mirabeau that the unfortunate Arthur was captured and carried off into the dark captivity from which he never emerged. Chaluz is too far away for any recollection to continue of the random arrow which took the life of the lion-hearted Richard. Poitiers is so far south, and the victory that the Black Prince won there was so humiliating to the French, that all memories of it have gone with the fleeting winds.

But every mile of this rather humid and pleasant countryside, and every twist of the narrow roads where horse-drawn carts are still more often seen than touring motor cars, invoke memories for those who want to refresh their knowledge of the first years of that fascinating family known as the Plantagenets.

CHAPTER II

The Long Years of Civil War

HENRY I of England, the youngest son of William the Conqueror, became a saddened man when his only son was drowned in the wreck of La Blanche Nef off the Norman coast. He had no appetite, he sat alone and stared at nothing, his temper was so fitful that the people of the court tried to keep out of his way, he did not pay any attention even to affairs of state, which was the surest indication of the mental condition into which this most painstaking of rulers had fallen. His chief minister, Roger of Salisbury, began to take it upon himself to govern and to issue writs “on the King’s part and my own.” This was too much for the rest of the royal entourage, who, of course, hated Roger. A concerted effort was made to bring the sorrowing man back to an interest in life, and he was finally persuaded, much against his will, to marry again in the hope of having a male heir to take the place of his lost William.

The wife selected for him was Adelicia, daughter of the Count of Louvain, an eighteen-year-old girl of such beauty that she was called the Fair Maid of Brabant. Rhyming Robert of Gloucester said of her, “no woman so fair as she was seen on middle earth.” Adelicia was gentle and understanding and she strove to be a good wife to the melancholy Henry, but she failed in the most important respect: she did not bear him children. The situation looked hopeless until the King’s last remaining legitimate child, the Empress Matilda, was left a widow by her aged husband and returned to England.

Henry’s interest in affairs of state revived in earnest with the arrival of his daughter. He proceeded with the vigor of his younger days to insure her succession to the throne, calling another parliament and demanding that her right be acknowledged by all. He had one precedent to quote in support of his claims. Serburge, die wife of Cenwalch, King of the West Saxons, had been chosen to succeed that monarch. This had happened a long time before, and Queen Serburge had reigned for one year only, after which the nobility had expelled her, not being able to stand any longer the humiliation of taking orders from a woman. If he had wanted to go back to Celtic days he could, of course, have mentioned Boadicea of immortal memory, but it is doubtful if he had ever heard of that spirited ruler. Support of this kind was not needed, however, for the assembled nobility decided unanimously in favor of Matilda. The first to take the oath was Stephen of Blois, son of Adele, the Conqueror’s fourth daughter.

Stephen was said to be the handsomest man in Europe. He was, at any rate, tall and striking-looking and debonair. There must have been tension in the air when he knelt before the young woman of twenty-four who had been an empress and pressed on her white hand the kiss of fealty.

The old Lion of Justice (this name for Henry came from some garbled nonsense of Merlin’s) lived for fifteen years after he married the Fair Maid of Brabant. He became less active and developed a liking for the mild pleasure of processionals about his domain. His radiantly lovely wife was always by his side, but the royal countenance remained as unsmiling as in the days following the death of his son and the end of all his hopes. He won another, and final, campaign in France and allowed himself an act of retaliation which seems more in keeping with the character of his father. A bard named Luke de Barré, who had once been on friendly terms with the English King, fought on the French side and was indiscreet enough to sing some ballads which held Henry up to ridicule. The unfortunate bard was captured, and Henry ordered that his eyes be burned out. The victim, who had always been a gay fellow with a great zest for life, struggled with the executioner when he was led out at Rouen and sustained such bad internal burns that he died of them. Perhaps the monarch felt some remorse, for he began after that to complain of bad dreams. In his sleep angry peasants swarmed about him, and sometimes knights who threatened his life. These nightmares became so bad that he would spring out of bed, seize a sword, and slash about him in the darkness, shouting at the top of his voice.

2

Matilda brought back three things from Germany: the richly jeweled crown she had worn, the sword of Tristan, and the most imperious temper that ever plunged a nation into conflict. Picture the long White-Hall at Westminster crowded with the people of the court waiting to see her, the men in their most be-banded and embroidered tunics; the ladies, with their hair hanging down over each shoulder in front in tight silk cases, and their sleeves so long that the tips almost swept the floor; the old King in his short black tunic and tight-fitting black hose over legs which were showing a tendency to shrivel, a massive gold chain around his neck at the end of which dangled a ruby worth a king’s ransom, sitting on his low throne chair and staring straight ahead of him with unseeing eyes and causing one of the long and intensely uncomfortable spells of complete silence which his courtiers had to suffer through. The first glimpse of her was most enticing: a fine-looking woman, truly regal, rather tall and graceful and with a way of carrying her head up which was an indication of her character, eyes dark and with a light in them, skin white.

She was displaying a garment which had come into an amazing popularity on the Continent but which was still new to English eyes, a silken sort of coat worn over her rich ceremonial gown. It had short sleeves and fell almost to the knees. Drawn in tightly at the waist, it flared out with such a gay effect that every woman there possessed one of them as soon as the nimble fingers of a lady’s maid could cut and snip and sew it together. This new garment was a pelisse, and it was perhaps the first important style departure of those early days. Matilda’s would be in one of the new colors she introduced to a country which had used only reds and blues and greens; violet, perhaps, or gold or rose madder; whichever it was, a shade to set off best her fine dark hair.

She met at White-Hall, of course, and for the first time, Stephen of Blois. How well he looked, this tall cousin, in his wine-colored cloak over tunic of silver cloth, his gray leather shoes fitting him tightly to the rounded portion of his handsome calves and then turning over to show lining of the same rich red of the cloak!

In the weeks which followed, the Empress saw many things which did not please her at all. The first glimpses of her father’s household had been disillusioning to the proud widow who had presided over the most brilliant court in the known world and in the Eternal City itself. She was puzzled to see groups of men standing about in the anterooms, common men who wore dull-colored tunics and some of whom had even allowed their yellow hair to grow so long that it hung down over their shoulders like an untidy woman’s. These ill-bred clods surrounded the King whenever he appeared and actually seemed to dispute with him. Were these uncouth fellows Saxons? Could this be the race from which her own lovely mother had come?

She was puzzled also that no commotion was created when that silent man, her father, entered or strolled down one of the royal corridors. When she, the Empress Matilda, had walked into or out of a room there had been court functionaries to carry four high-arched iron candlesticks in front of her, the lights flaring and flickering with the motion and the drafts, and a seneschal in the lead intoning, “Her Supreme and Excellent Lady and Most Royal Highness!”

Particularly disconcerting was the fact that the aging but still impatient Henry wanted church services hurried so he would not have to spend much time in chapel. His daughter remembered how this had hurt her devout mother and what talk there had been when the King had made a certain Roger le Poer his own royal chaplain because that clever rogue knew enough to keep his exhortations short. Could it be that the aging and corpulent ecclesiastic who was now jumbling the Latin phrases and wheezing in his haste was the selfsame Roger? She was horrified to find that it was and that he now filled as well the high post of chancellor. She thought of the great cathedrals of Germany and Rome where the Gregorian chants, intoned by hidden choirs of trained singers, made her flesh tingle with delight, and of mighty chords crashing about her ears from the bronze pipes of the organs.

It was not long before London was dumfounded to learn that the Empress, after this triumphant return to her father’s court, had retired from the public eye. She had withdrawn herself into the household of Queen Adelicia in the Cotton-Hall at Westminster and was not seeing anyone. Tongues clacked furiously, and a score of reasons were advanced for this strange state of affairs. It is doubtful if anyone guessed the exact truth.

The real reason was that the ex-Empress was refusing, emphatically and passionately, to concur in the marriage with Geoffrey of Anjou on which Henry had decided, the young man who had fallen into the habit of wearing the planta genesta in his hat. She had many good reasons for objecting to this match. She had been an empress and for eleven years had outranked all the queens of Europe. Must she now marry a mere count, a descendant, moreover, of some wild creature of the woods called Tortulf? Geoffrey, apart from his comparatively humble station, was thoroughly unsuitable in her eyes. He was a youth of fifteen years, and it could be assumed that his interests had not yet risen much above the horse and dog and brawling stage. What kind of husband would this adolescent ignoramus make for an accomplished woman of twenty-five?

She remained in seclusion for several months, and during that time there were many violent discussions between father and daughter, and much raising of voices and protesting of vows and stamping of feet. The Empress seems to have continued, however, on the friendliest of terms with Adelicia, although it would have been hard to find two natures more diverse. The beautiful and gentle Queen entertained a real affection for her dark and willful stepdaughter, who was practically her own age. How the Empress occupied herself during the long days and interminable weeks is difficult to guess. Adelicia was given to fine needlework, and it was the custom of her ladies to gather about her each day in the sunniest apartment of Cotton-Hall and assist her in this work. This was an activity in which the restless Empress could not have played much part.

How the artful King succeeded in winning her over is not known. Behind the gloomy eye an agile and crafty mind was still at work. He was hard to resist long, this devious tactician who had found means of getting his own way all the years of his life. Somehow the daughter was persuaded to consent. Certainly her father employed the argument that she was to be Queen of England and that they were selecting nothing but a consort. At any rate, give in she did, emerging from her retirement with a smoldering air of resignation. Henry went to Normandy himself and saw to it that the nuptials were solemnized by the Archbishop of Rouen on August 26 in the year 1127.

That the marriage had been a mistake was apparent from the first. Even Henry, the matchmaker, must have realized it. Three times the Empress left her husband and her dark eyes flamed mutinously as she explained her reasons to her rapidly aging father, and three times the smooth tongue of the consummate diplomat encouraged her to go back to Geoffrey. Finally, after more than five years without issue, she raged back to England and declared that this time the separation was final. She was able to convince Henry of the iniquities of her still adolescent spouse, and he allowed her a long stay before exerting any pressure on her to return.

When Henry finally told the Empress she must return to Anjou, she seems to have agreed without much protest. England was at peace after that, and there was little for the King to do but sign the writs which Roger the Treasurer laid before him. A disastrous fire swept London, cutting black swathes on both sides of the Thames. Henry thought of going to his new palace at Woodstock, where he had collected a menagerie and which he liked to visit, but the pleasure to be anticipated did not seem to justify the rigors of the journey. Time, of which he had never had enough, seemed at last to be standing still; waiting, perhaps, for younger and more active participants. And then one day he received news which sent him skurrying to the Cotton-Hall, his feet recapturing some of the spring of youth. His eyes had lighted up and the message they conveyed to Adelicia was easy to interpret: “At last, sweet child, it can be forgiven you that I have no son.”

Matilda’s son Henry had been born. Historians say that the nation rejoiced, but that statement has a spurious ring. The arrival of an heir made it certain that one day a scion of the much feared Angevin family would sit on the throne. Certainly there could not have been any rejoicing in London, where English opinion was cradled. It is impossible to conceive of these independent thinking burghers throwing their hats in the air because a man-child had come into the world who might someday try to trample on their hard-earned rights.

Events followed rapidly thereafter. The King went to Normandy to see his grandson, his cook put too much oil in a dish of lampreys, and the end came to a long and in some respects a memorable reign. And back in England all men paused in dire apprehension and wondered what would happen now.

3

Stephen was at the bedside of Henry, and he heard the dying King give instructions to Robert of Gloucester, who stood on the other side of the couch, for his burial. He heard also the low tones in which Henry asserted that he bequeathed all his dominions to his daughter.

Could any intimation of coming events, of the struggle they would wage between them, have communicated itself to these two men who saw the old King breathe his last? Stephen would have been more likely to sense what was ahead than the other. Robert of Gloucester was one of Henry’s score of natural children, the best of the lot, his mother a Welsh princess named Nesta who had been made a prisoner during some fighting along the Marches. He was a man of lofty ideals, of great courage and compassion, a capable leader and soldier. It would not occur to one of his high honor that the wishes of the dead monarch might be set aside, and it is unlikely that he entertained any suspicions when Stephen disappeared abruptly.

Stephen made a night crossing from Wissant, and it was dawn when he landed near Dover. A sleet was falling which turned the roads into sheets of ice. The warders at Dover had been expecting arrivals of this kind, and they refused to allow Stephen and his small party of knights inside the gates. Stephen knew only too well his great need for haste, so he did not linger to dispute the matter. In addition to the Empress, who would have heavy support in view of all the oaths which had been sworn, there was his own older brother Theobald, who also had an eye on the diadem of Henry.

The repulse at Dover sent the first of the claimants galloping over the road to the north. The icy surface struck sparks from the hoofs of the horses, and some of the riders had falls. Reluctantly, then, the ambitious earl turned off the road and led his supporters over the fields to London.

Although his intentions had been known to some and he had even gone to the extent of forming a secret party pledged to his elevation, not one man joined the bedraggled group as they rode in dismal spirits from mark to mark and town to town. It was a disappointed lot who saw finally the smoke and the roofs of the great city on the horizon ahead of them.

How different it was here! London was for Stephen, and London did not fear to proclaim the fact to the whole world. No skulking behind high walls for these stout makers of cloaks and sellers of corn! They rushed out in excited droves to meet him, and Stephen found himself surrounded by vehement friends who tossed a dry cloak over his shoulders and placed a flagon of hot wine in his hand and who fairly hung to his stirrups as he slowly finished the last stage of his dangerous ride. “Stephen is King!” was the cry he heard on every side.

Stephen was King. The stouthearted citizens had settled the issue. They called together their folkmote and agreed on him unanimously as the new ruler. There was not a nobleman present, but the mere fact of his selection seems to have carried the necessary weight. Members of the nobility began then to come in and give their submissions. This was not due to any feeling against the Empress but rather to the fact that every man realized the need for a strong hand at the helm. No stage of history was less propitious for an experiment in female rule. In addition, Matilda was in Anjou with her well-hated husband, and Stephen was on hand, ruddy and smiling, his arms stretched out in friendship for all men. In a very short time the popular earl was able to ride to Winchester with a substantial train of backers, including some of the best known of the Norman aristocracy. Here he made his formal demand for the crown.

He was reluctantly received by the archbishop, but the ministers of the late King went over in a body to the winning side. The seneschal went still further by swearing that Henry, with his last breath, had passed over his daughter and selected Stephen as his successor. This was a palpable falsehood but the kind of thing, nevertheless, which carries weight. The upshot of it all was that Stephen was allowed to break the seals on the stores at Winchester, finding that the old King had accumulated savings of more than one hundred thousand pounds as well as a great collection of plate and jewelry. With this in his possession he was free of all competition.

The reign of Stephen is important for this one thing only, that a truly revolutionary precedent had been set. Common men had chosen a king!

Stephen was crowned on Christmas Eve. Queen Matilda was on hand, of course, hardly daring to look at her beloved husband in his new glory, and their young son Eustace, who would become King of England himself in God’s good time, or so it seemed. The new ruler made fair promises (and meant to keep them), confirming the laws of Henry and agreeing in addition to relax the royal control of the forests.

The Empress had made no move. What she thought of Stephen’s treachery (not too strong a term in view of his public pledges and the personal avowals which most certainly had been made between them) can be imagined. She was shackled at the moment by the incompetence of her unsatisfactory husband, whose misrule of his own dominions had caused an uprising. When Geoffrey found himself in a position to do something for his wife’s cause, he led some troops into Normandy, expecting that the people of the duchy would rise to accept their rightful ruler. What the Normans did was to shove him back into his own territory with such angry vigor that he lost his appetite for further efforts along that line. All the Empress could do, therefore, was wait.

She did not have to wait long. Stephen proved a very poor administrator. Fully conscious that his personal popularity had won him his crown, he felt he could hold it on the same basis. He was prone to smile and say “Yes” to suggestions which should have been met with a frown and an emphatic “No.” Having thrown the kingdom into serious disorder with his ill-advised leniency, he then reversed himself, as weak men always do, and became unduly harsh. He proceeded to throw his nobles and his bishops, including Henry’s old ministers, into prison on the most insufficient of pretexts. The country, accustomed to the even and just, though stern, rule of Henry, became uneasy. What kind of king was this?

Robert of Gloucester, that wise and honest man, had been waiting and watching. Convinced that the hour had struck, he raised his sister’s standard in Normandy and soon had a full half of the duchy in his possession. At the same time King David of Scotland came swooping down on the northern counties with an army of Highland clansmen and imported Galway levies. The result here was favorable to Stephen. The savagery of the invaders, who wasted the country as they advanced, rallied the people against them, and the English won a most bloody encounter at Northallerton. It has come down in history as the Battle of the Standards because the northern bishops combined their banners on a single pole which was elevated above the ranks. This setback, however, did not alter the plans of the Empress and her half brother. They landed the following year at Portsmouth with a party of only one hundred and forty men, firm in the conviction that the nation would rise against the inept usurper. They had in their pockets, in fact, the promises of many of the nobles to join them.

The Dowager Queen Adelicia had remarried in the meantime, her second husband being William d’Aubigny, son of William the Conqueror’s cupbearer. This new husband was a handsome, brave, and honorable knight, and it had been in every sense a love match. They were living at Arundel Castle, which Henry had bestowed on his wife, and so the saying, did not apply to this particular juncture, Adelicia’s husband not being awarded the title until the next reign. The great castle stood close to the coast of Sussex, and the Empress and her party stopped there, asking shelter of the ex-Queen. The dowager very wisely had taken no part in national affairs and had held aloof from support of, or opposition to, the incumbent. Now, however, she threw open the gates of the castle and received her weary stepdaughter with warmth and affection. Realizing the need for quick action in raising the country, Robert of Gloucester rode away to Bristol, leaving his sister at Arundel.

Since William rose and Harold fell,There have been earls of Arundel,

The chatelaine of Arundel had grown still lovelier with the passing of time, although she was probably a shade more matronly in figure. By her side when she welcomed the Empress was a young son, William, who showed signs of inheriting from his father the fine physique which had won the latter the name of Strong Arm. In a cradle close at hand was a second son, Reyner. Adelicia had borne Henry no children, but she was to go on bringing sons and daughters into the world for her second husband: Henry, Godfrey, Alice, Olivia, and Agatha.

To this late blooming of the fair dowager, the Empress presented a rather sad contrast. The frustrations and disappointments to which she had been subjected had taken an inevitable toll. Her dark eyes had lost all trace of softness. As she had not had any opportunity since setting out to make use of the contents of the dye-beck she carried in her saddlebags, there were streaks of gray in her once lustrous black hair. She was thin and showing every indication of nervous strain, and her voice would sometimes rise to a shrill note.

Stephen acted in this crisis with dispatch. He appeared before Arundel Castle and demanded that the Empress be delivered into his hands. This put Adelicia and her husband in a most difficult position. The castle was strong, but at this juncture they had only the peacetime complement of men there, a few squires and a handful of men-at-arms, and a drove of servants who would not be of much use. Stephen, on the other hand, had with him a sufficient force to carry the castle by storm.

The situation which had arisen in England was of a nature to bring out in the main participants their real characteristics. Stephen was showing himself brave and chivalrous but also as an insufficient opportunist. The Empress was to throw away a kingdom through sheer arrogance and an uncontrollable desire for revenge. Queen Matilda was to become later a national heroine and to perform prodigies of daring and faith for her unfaithful husband. Adelicia, more than the rest, was to come out in a new light.

This gentle lady, who had sat so unobtrusively and so decoratively by Henry’s side, sent out word to Stephen that she would protect her stepdaughter and friend to the last extremity!

And now Stephen proceeded to do one of the most generous but decidedly one of the most stupid acts of his life. He sent in a safe-conduct for the Empress to join Robert of Gloucester at Bristol, appointing his brother, the Bishop of Winchester, and the Earl of Mellent to escort her. Then he waved jauntily up at the battlements and rode away with his troops! By this he proved that he had an honorable side to him and that he could respect a memory. But by the same act he unleashed the forces of civil war and condemned the English people to fourteen years of the most abject misery. Chivalrous gestures often produced results such as this.

4

The presence of the Empress in England roused to armed action the enmities Stephen had created. The barons, pretending a sudden uneasiness of conscience on the score of their vows, came out in large numbers for the daughter of Henry-Talbot, Fitz-Alan, Randulph of Chester, Mohun, Roumara, Lovell, Fitz-John. “They chose me King!” cried Stephen, unable to understand these defections. “Why are they deserting mer Like all weak men, he did not see that the fault was in himself. He tried to prepare for what was coming by bringing in mercenaries from Flanders under the command of a very capable soldier named William of Ypres. This was a serious mistake because the people of England resented these hired troops bitterly and tended more and more to favor the cause of the Empress. In the meantime Queen Matilda took her youthful son Eustace to France and negotiated a marriage between the boy and the Princess Constance, sister of Louis VII, in the hope of cementing an alliance.

The war which now broke over England with full fury fell into a certain pattern. The west was for the Empress; London and the eastern counties remained loyal to Stephen. In some parts of the country the barons found themselves divided in their allegiance and so tinder the necessity of making war on each other. Everywhere was heard the clash of arms, the tumult of armed forays, the grim echo of sieges. All attempt at national maintenance of law and order, the goal which Henry had achieved with such effort, had ceased. What remained was the justice of the overlords and the sheriffs, or viscounts as they were called then; and judgment of this kind was cruel, sharp, and summary.

The first important victory was won by the forces of the Empress. Stephen had taken a small army of his Brabançon mercenaries to oust the other faction from the city of Lincoln. While he was about the tedious and bloody business of ferreting them out of reinforced corners, Robert of Gloucester appeared suddenly on the scene with a much larger army. It was Candlemas Day and very cold, and Stephen was taken completely by surprise when they swam the icy waters of the River Trent and came in behind him on the other side. The wisest course for the King would have been to get away as fast as he could and with as little loss as possible. Stephen, however, elected to fight it out, a decision in which his followers did not concur, a small part of them only remaining to stand behind him. It is a favorite device of the chronicles, in fact, to depict the handsome King as holding the hostile forces at bay singlehanded. Matthew Paris, who has been responsible for introducing much high-flown fiction into English annals, describes Stephen as “grinding his teeth and foaming like a furious wild boar” as he fought on alone. There can be no doubt that the King gave a good account of himself, laying about him with his battle-ax. When this was broken he resorted to his heavy two-handed sword with which he did great execution also. In the end he went down, and a common soldier, coming across him as he lay unconscious among the dead, cried, “I have found the King!”

He was taken to Gloucester, where the Empress was in residence, and shoved into one of the tiny and almost airless rooms scooped out from the thick walls of the castle. The records make no mention of a meeting between the two rivals, but it is certain that Matilda had Stephen summoned to her presence. Not sufficient for her that he was now her prisoner and that the crown was within her grasp; the proofs she gave later of a hunger to taste to the fullest the sweets of triumph and retaliation make it clear she would not send him off to the imprisonment she had arranged for him at Bristol without a single chance to vent her feelings. There was at least one meeting, of that we may be sure, and it is equally certain that Matilda heaped him with reproaches.

Despite the briefness of the time he was kept at Gloucester, however, Stephen succeeded in aggravating the temper of the Empress to an even more bitter ferment. One of the chronicles thinks this was due to an attempt at escape. Whatever the cause, he was heavily loaded with chains and taken to Bristol. No safe-conducts to Bristol this time! People crowded the roads and filled trees and church steeples when he passed, as indeed they might, for this was an unusual spectacle, the King of England shackled to his saddle.

In the meantime the Empress made a triumphal entry into Winchester and was met at the gate by the bishop, who was Stephen’s brother but who knew when a change of coat was advisable. She followed the usual procedure of scooping in whatever was there in the way of royal treasure. A court of nobles and bishops was invoked and a quick decision reached. Robert of Winchester announced it. “Having first, as is fit, invoked the aid of Almighty God, we elect as Lady of England and Normandy the daughter of the glorious, the rich, the good, the peaceful King Henry; and to her we promise fealty and support.”

The new Lady of England might well have thought that a somewhat unnecessary emphasis was thus laid on the merits of the deceased King and that too little was said about her. If she felt that way, she undoubtedly let them know it. Victory was not sitting well on her shoulders. She was becoming more arrogant by the hour, more determined on retaliation, less prone to listen to reason, even when reason spoke to her in the tones of her sagacious brother, to whom she owed her elevation.

5

Stephen’s Queen Matilda returned from France to find her husband’s cause in complete eclipse and his person in the hands of his unrelenting adversary. It is clear that Matilda’s regrets were for the plight of her lord and not at all for the honors he had lost. This is made evident by the appeals she addressed to the Empress, all with one purpose, his release. She had dreadful visions, this faithful wife, of her husband immured deep under the earth and left there to rot in misery and rags. Perhaps she feared even more violent measures, the barbarous tortures to which prisoners were too often subjected.

At any rate, she took it upon herself to make promises. Stephen would relinquish all claim to the throne and leave England, she declared. This having no effect, Matilda went much further and made an offer which proves she had been aware all along of the attachment of the Empress for Stephen and of his response. She promised in his name that he would not only renounce all pretensions to royalty but would leave England and devote himself to religious observance and that she herself would engage never to see him again, the only stipulation being that their son Eustace was to retain the earlship of Boulogne, which had been hers, and of Mortagne, a special grant from Henry to his favorite nephew.

Perhaps never before had a woman so humbled herself to a triumphant rival. Matilda was stating her readiness to spend the balance of her life in loneliness if there would be enough satisfaction in that for the Empress to strike the shackles from Stephen’s wrists. In that savage era the figure of Stephen’s Queen stands out in sharp and grateful contrast, a bright gleam of light in the prevailing dark.

The Empress rejected this last appeal with scorn. It was assumed that she objected to allowing them Boulogne and Mortagne and wanted to reduce the whole family to penury. This had nothing to do with it. The Empress had no intention of releasing Stephen on any conditions which might be conceived. Nothing she had ever experienced in life had given her as much satisfaction as the knowledge that he was chained in a dungeon, that he was in her power, that she could turn him over to the rack or the boot or bring about his death with a movement of her hand. No, the Empress did not intend to give up Stephen so long as there was breath in either of their bodies.

Failing in her efforts to secure Stephen’s release, Matilda decided to fight. With the assistance of William of Ypres, she roused the men of Kent and Suffolk, who had always been for Stephen, and created the nucleus of another army to contest the kingdom. Some historians say she rode in armor at the head of these eager volunteers, but there is no mention of it in the records. Certainly it would have required the most careful use of the armorer’s hammer and chisel to create casque and hauberk to the delicate proportions of the Queen. It was not unusual at that time, however, for ladies to take the field and to ride and fight, and even swear the oaths of their husbands and fathers. A troubadour named Rambaud de Vaqueiras has written of seeing through a half-opened door a lady of great beauty and apparent delicacy drop her skirts to the floor, take a sword from the wall, toss it in the air like Taillefer at Hastings, and then go through a series of sword exercises which left him dizzy.

In the meantime, while Matilda organized forces to go on with the struggle, the victorious Empress, fresh from her election as Lady of England, came to London; for not until London acquiesced could the crown and ermine be properly bestowed.

Unfortunately for the prosperity of her cause, the Empress arrived in the full glow of victory and with the intention of imposing her will. The citizens of the great town, believing the struggle over and conscious of the fact, as one of the chronicles says, “that the daughter of Mold, their good Queen, claimed their allegiance,” were prepared to accept her. When a deputation appeared before her at Westminster, it was at once clear, however, that the lady who received them with haughty reserve and frown was no true daughter of their gentle Queen Mold. Norman to her fingertips, to the inmost recesses of heart and mind, the Empress was not ready to reason with them.

Nevertheless, these men of London, who still called themselves by such Saxon titles as chapman and burgess and butsecarl, spoke up stoutly for a renewal of their charter. The answer of the Empress was a sharp demand for the immediate imposition of a heavy tax called a taillage.

“The King has left us nothing,” declared the chief spokesman.

The Empress looked at these men who had put Stephen on the throne in the first place and who now stood before her, with caps in hands, it is true, but with no bending of knees, no cringing for her forgiveness and favor. She could hardly contain the rage created in her by the sight of them.

“You have given all to my enemy!” she cried. “You have made him strong against me. You have conspired for my ruin, and yet you expect me to spare you!”

The Londoners now understood the situation they faced, but they showed no signs of giving in. They demanded instead an assurance that she would rule by the laws of Edward the Confessor and not by the exacting methods of her father, who had been oppressive as well as just.

Robert of Gloucester stood at his sister’s shoulder and it is certain that he whispered to her to be calm, to weigh her words, to dissemble if she could not agree. If she heard him, she ignored his wise counsel. Instead she raged at the deputation, calling them rebels and base dogs of low degree, finally driving them from her presence with threats of what she meant to do.

When the Londoners left it was plain to Robert of Gloucester and the rest of the group about the Lady of England that a serious mistake had been made. They had been disturbed by the unbending attitude of the merchants, the independence shown as they withdrew in a silent body.

That same evening their fears were confirmed. The Empress was entering the White-Hall where supper was to be served, preceded perhaps by four tall iron candlesticks in the hands of court servants, when the bells of London began to ring. London had many churches, and when the bells joined in together, the clamor could either heat or chill the blood. It meant news of disaster, a summons to arms, or a wild paean of triumph. This time it was a summons to arms, the leaders having taken counsel among themselves and deciding to resist the exactions of the Norman woman. In a trice the streets were filled with armed men shouting defiance and converging by preconceived plan on the precincts of Westminster.

Robert now gave a piece of advice which was heeded, “To horse!” Without waiting to change her clothes, the Lady of England mounted and rode at top speed from the city with her brother and a party of her closest adherents. They did not realize it then, but as soon as those bells started to toll she had ceased to be Lady of England.

The fleeing party rode hard and fast, allowing themselves few stops for rest, until they reached Oxford, where they finally came to a halt. It is said that after each stop several faces were missed from the ranks. Doubts had entered the minds of the barons. They were no longer sure they wanted as ruler a lady of such haughty temper.

6

Now the struggle was on again. The Londoners swelled the ranks of the men from Kent and Suffolk, and under the lead of Matilda and William of Ypres they advanced to the siege of Winchester. The forces of the Empress, led by Robert of Gloucester and her uncle, King David of Scotland, decided to make this a test of strength by marching to the relief of the city. Stephen’s bishop brother had changed back and had ensconced himself in his strong episcopal palace which lay outside the walls and from which he rained fireballs into that storied city of high church spires. In the course of the struggle, which lasted nine weeks, a score of the fine churches were destroyed and whole sections were laid waste. The army of the Empress was finally compelled to retreat. Robert of Gloucester, fighting a rear-guard action to cover the escape of his sister, was made a prisoner.

Now the situation was much improved from that desperate phase when Matilda had made her pathetic proffer to her stern rival. Being scrupulously careful to have the new captive comfortably housed and kindly treated, the Queen offered to trade the brother of the Empress for Stephen, who was still, from all reports, shackled to the wall of his Bristol cell. The refusal of the Empress was as short and sharp and peremptory as ever. Her brother was so completely the soul and brain of her cause that his absence might very well bring her to disaster; knowing this, she still held out. Twelve captive earls she would give and even throw in a sum of gold, which was getting scarce in both camps, but not Stephen.

Then the Queen went direct to the Lady Amabel, who acted as keeper of the person of the King. The Lady Amabel did not stand on ceremony, nor did she consult the Empress in the matter. She had heard that Robert was to be sent to one of the massive Norman keeps in Boulogne where, presumably, he would find captivity as hard as Stephen. Before the Empress knew what was in the wind, the two wives had agreed to trade even. Stephen, a free man, rode in to Winchester to be greeted by his victorious Matilda, a sadder, certainly, but not much wiser man.

The war dragged on for several years, the one dramatic occurrence being the siege of Oxford Castle into which the Empress had withdrawn while her brother went to Anjou for her young son Henry, it being thought that the presence of the princeling would inject new enthusiasm into a waning cause. The attack was pressed by Stephen with such vigor that it soon became apparent the defenders could not long hold out. When things reached this desperate pass, the Empress and four of her supporters garbed themselves in white robes and ventured out from a postern which opened on the river. It was in the dead of winter, the ground was covered with deep snow, and a blinding storm was sweeping down from the north. The sentries posted along the river did not see the five ghostly figures fighting their way through the lines. After as grueling a struggle with the elements as any woman ever endured, the party reached a village to the west where horses were obtained.

While the rival claimants continued the contest with siege and countersiege and foray and skirmish, merrie England became the least merrie country in the known world. As no attempt at administration was made in a land given over to factional strife, the barons became the rulers. Each was now a petty king. They did as they pleased, seized everything they wanted, from the lands of a freeman to the pretty daughter of a villein, turned their tall castles into headquarters for an iron oppression, and built new ones at points which made possible the extension of their operations. In the dungeons of these castles the instruments of torture were installed: the rack, the thumbscrew, the boot, the chambre à crucit (a chest lined with sharp stones into which bodies were forced until muscles were torn and bones broken), and iron chains on which men were suspended by heels or thumbs over slow fires. A favorite device seems to have been a knotted rope which was bound over the temples and tightened by degrees until the knots cut into the brain. If a baron needed labor for the building of a castle or a dam or the laying of new roads, he rounded up everyone he could find, women as well as men, and set them to work with guards over them, like the chain gangs of later years. A special tax, which all the baronage seems to have adopted and which was completely illegal, was imposed on towns and villages and called tanserie.

Thus, while the matter of the succession was disputed, England suffered and starved. Few crops were put in because the barons were likely to take the harvest for themselves or destroy it in sheer wantonness. One chronicle says the people became afraid that God and all His saints were asleep.

As an added stimulus to confusion and struggle and hate, the two rivals were bidding contentiously for the support of such of the nobility as remained neutral or undecided. Lands were granted lavishly, titles were distributed wholesale, every kind of inducement was offered to bring the laggards into camp. The result of this bribery was that many properties and honors had two claimants, so that private wars were fought at the same time that the armies of Stephen and the Empress advanced and retreated and struck here and struck there in the strategic conception of the day, which was to avoid battle and concentrate on siege. Stephen went so far as to create batches of titular earls to please the vanity of his lieutenants. An earl had been an officer of the Crown with the supervision of a county. As Stephen’s course was followed by later kings, the title ceased in time to have any official significance and became instead a badge of aristocracy.

Robert of Gloucester died on October 31, 1147, and, realizing that it would be useless to fight on without the aid of that strongest prop of her cause, the Empress followed her son to Anjou, and the struggle ceased for a time. Certain that the threat to his royal tenure had now been removed, Stephen tried to have his son Eustace accepted as his successor. A few of the nobility took the oath of fealty, but the majority held aloof, a sign that the peace was on the surface only.

Four years later Stephen suffered his greatest loss in the death of his Queen. This admirable lady had been so worn out by anxiety and the stress of war that she had little strength left to enjoy the peace she had done so much to bring about. She passed away at Heningham Castle in Kent on May 3, 1151, and was buried in the abbey of Feversham, which she and Stephen had founded in their gratitude for victory.

But the war was not over. Henry Fitz-Empress was growing up and showing already the decision of character and sagacity of mind which later were to make him an able king. Geoffrey, his father, the handsome youth who had become such a futile man, was now dead and Henry had assumed the government of Normandy. When Eustace appeared at the French court and was invested with the duchy by Louis, the young Henry realized that the time had come to settle the issue once and for all. He organized a small force and landed in England in January 1153, setting up his mother’s standard and summoning her supporters to take up arms again in her behalf. Enough of them responded to swell his ranks to formidable size, and he marched toward Wallingford in readiness to do battle. Stephen’s men held the northern bank of the Thames in equal readiness.

The stage was now set for the first pitched battle of the war, which would also be, without a doubt, the decisive one. Most of the dramatic moments of this internecine strife had come in the dead of winter, and this was no exception. The banks of the river were heaped high with snow, and there was ice on the surface of the water. A fierce wind tossed and tore Stephen’s banner, with its leopards, and did the same for the Angevin banners on the other shore.

And then, as the knights tested the edges of their swords and the squires greased harness with avid fingers, a gleam of great good sense came to one of the combatants. This was William d’Aubigny, a widower two years and still disconsolate over the loss of his fair Adelicia. He seems to have been on the King’s side of the river. At any rate, he went to Stephen and protested that the peace of the country should not be disturbed further when an amicable arrangement should be possible to arrive at. Some historians credit Archbishop Theobald with being the agent of peace, but it is not important who was responsible for the urgent suggestion that the stage of the olive branch had arrived. The important thing is that Stephen rode down to the river on his side and young Henry Fitz-Empress came up on the south and a conference was held from bank to bank. The result was peace at last, a solution of the differences which had reduced England to such desolation.

Stephen was to be King for the balance of his life and Henry was to succeed him. The Treaty of Wallingford, as it was called, provided, moreover, that Stephen was to disband his mercenaries and send them out of the country, the new castles were to be razed, and new sheriffs were to be appointed to proceed with the restoration of law and order.

At this point Matthew Paris peers once more around the backdrop of history and prompts the chief actors with words of his own. The Empress, he declares, was at Wallingford and the settlement was due to her efforts. “The Empress,” he writes, “who would rather have been Stephen’s paramour than his foe, they say, caused King Stephen to be called aside, and coming boldly up to him, said, ‘What mischievous and unnatural thing go ye about to do? Is it meet the father should destroy the son, or the son kill the sire? etc., etc.’ ”

This, of course, has no roots in truth. The Empress was not in England when these events occurred, and had she been there, her last thought would have been to counsel peace. Not that resolute lady whose whole life had been dedicated to the winning of the crown! There are certain pieces of evidence on this point, however, which make the possibility of Henry being the son of Stephen a little more than mere surmise. The Empress was in England the year before the birth of the prince and swore at first furiously and definitely that she would not go back to Geoffrey, then changed her mind hurriedly. In some sources it is said that Henry called Stephen his father during the cross-water negotiations, a statement which seems to carry the hallmark of invention on the face of it.