10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Aderyn Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

When Francis House enlists in the British Army in 1907, at the tender age of fifteen years and three months, he is not thinking about war. He imagines he simply wants to earn his stripes – to ease his traumatised father's Boer War memories, or perhaps to please his favourite sister, Lily, with whom he has always dreamt of adventure. But he soon discovers that simply becoming a soldier is not enough and, against the advice of his sergeant, he determines to seek out a real fight. Wading ashore at Gallipoli seven years later, Francis thinks he might just have found the site of his greatest opportunity. Here, he thinks, he might finally prove himself a man. First, though, he must find his missing friend Berto. He needs to say sorry. He cannot yet imagine the ghosts that might stand in his way.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THE EMPTY GREATCOAT

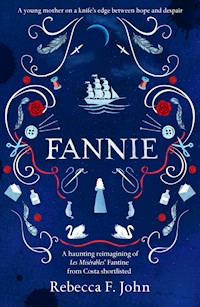

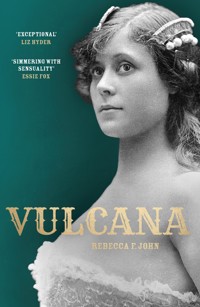

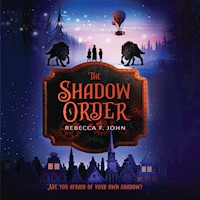

Also by Rebecca F. John

Clown’s ShoesThe Haunting of Henry Twist

To Sergeant Francis Albert House, for all he did.And to the millions whose names I do not know.

One

‘Listen!’

A low, muted moon striates Captain Burrows’ face as he leans in to whisper to the men. Beneath, the water flutters and gasps. Listen. Hush. Corporal Francis House concentrates on the orb of spittle which glints from the corner of his Captain’s ruckled lips and waits for it to drop.

‘Listen,’ he hisses again. ‘When we’re within six yards of land, we’re to step into the shallows and wade ashore.’

The men strain to hear him over the tattling waves. They hunch, fidget, sniff. Burrows adjusts his position, props his elbow on a muscled knee and continues, splaying his fingers with each word until his knuckles are tight and pale.

‘Be cautious. Men have drowned under their kits in these waters, but whatever happens you must – not – make – a – sound. Do you understand? Here are your orders. If you are drowning, drown – quietly.’ The fingers stretch further in the black air, as if reaching for something they cannot find. ‘If you are shot, bleed – quietly. You will not touch that beach if you utter a single sound, I can promise you that. Bill will hear you. Silence is your only hope.’

At this, the men sit back, withdrawing as far as the crowded barge will allow them from Burrows’ blunt words. Francis bites down on the inside of his cheek and braces himself against the movement: he will not shrink with them.

All around is darkness and stifled silence. Francis swallows the urge to cough. In his throat, the scratch of that morning’s square of kommissbrot and sea salt.

‘Do you understand?’ Burrows asks.

The men have been warned against speaking, and so they wait, shuffling on the spot, while Burrows shifts his attention from one pair of gleaming eyes to the next and extracts their nod of confirmation. Yes, Sir, their juddering chins reply. Yes, Sir, say their gathering tears. But the claggy stench rising from their underarms claims otherwise. They can feel war on the stagnant air now. Ashore, the glimpsed flare of guns and spit of rifles mount to a pip-pipping firework display, and their mouths fish open as they realise, man by man, that they are at last under fire.

Francis tastes someone else’s stale breath thrusting over his tongue and clamps his mouth shut. He is nauseated. He hadn’t known, until now, that dread could melt your innards.

A few gasps go up as a Turkish bullet, two, dent the tramp’s funnel and, with a dissonant clang, arc away. Francis peacocks his broad chest, keen to demonstrate control of his nerves: he is Corporal House now, for Christ’s sake; he has been entrusted to lead these men in Captain Burrows’ stead; he must slough away that idiot who’d spotted an orange box floating off the Maltese coast last summer and, thinking it a submarine, brought hell down on its splintered slats; he must inhabit his bravest self again.

A second cluster of bullets pings into the funnel just above their heads and, this time, Francis cannot help but duck. Despite the heat, gooseflesh rises along his neck. This really is it. They are under attack. And how different it is to the imagining. There is no room for bravery or heroism here. They must simply teeter together, forty-two men trapped on a round-topped barge, attempting to hold on to their kit and their rations and their balance. They cannot lift their guns. They cannot strike the enemy in close combat. They are jammed between the six-inch howitzers and their fear and, try as he might, Francis cannot even sight the beach. They are drifting slowly towards Anzac Cove. Helpless. And Francis had wanted this. Begged for it even.

Six months earlier, chin to the ceiling in the coffee and pipe tobacco fug of Lieutenant Cruikshank’s office at St Elmo, he’d demanded to be taken off that great, weather-beaten star fort. He wanted off Malta. He wanted action. Whatever far-flung post Berto Murley and Busty Leonard were destined for, Francis House was determined to follow. He was puffed up with bravado and ignorance.

‘You don’t know what you’re asking,’ Cruikshank said evenly. ‘And I won’t hear you ask it again. Now go, hmm.’

Hmm. Always that hmm with Cruikshank. Francis wanted to shake him: for the way it signified that he was mulling you over; for the pretension. Had Francis been told then that someday he would take comfort from that repeated hmm, that someday he would miss it, the disbelief would have led him to laughter.

And yet, as the men await Captain Burrows’ next command, Francis finds himself listening for it. He understands now that Cruikshank was correct: he hadn’t known what he’d been asking. He could not have foreseen any of this. He and the forty men he cajoled off Malta with his grins and promises are about to stumble into unknown silt, in deepest black, without the slightest idea of the conditions they’ll be under, and their sole objective is silence. They are not to disturb Bill. But none of them knows who Bill is. Francis cannot begin to guess, and it makes him feel a clown, and that is no way to proceed into battle. He cannot write to his father of confusion and cowardice. He is under his own orders to make Frederick House proud.

He is under his own orders, more importantly, to find Berto.

Fear drops through Francis’ chest, heavy as an iron bullet. He needs to move – to drag off his kit and dive into the waves and swim until his every muscle hurts. After all, he belongs to the sea. He always has. He marvels, even now, that only Lily ever understood that.

The last time they went to the beach together, just the two of them, it was fallen-leaf brown and disappointingly flat under a wet grey slick of afternoon sky, but Francis didn’t mind a jot. He was not yet ten. He was a sea child, a salt sprite.

‘I don’t think you’re a House at all,’ Lily called, laughing, as he swooped around her. ‘I think you’re a sea urchin.’

Oft, Lily told him stories of how some quick-finned creature had stolen in through the window one moony night while the true Francis House lay asleep in his cot and replaced her little brother with a swaddled merchild. She had no better explanation, she said, for the way he seemed to transform when the coast winds battered him, until he was composed of feathers or scales or spindrift. When he tore off his shoes and raced across the sand, he was a herring gull, complete with hungry beak and ready wings. When he dove into the waves, he was a glimmering bream.

He aches suddenly for the sister he has not seen these past four years. He aches to show her the actuality of all that adventure they had dreamt of; to stand alongside her again and peer outwards instead of in; to kick and overarm himself all the way back to Plymouth and say, ‘Wasn’t I foolish, thinking myself capable of so much.’

But Burrows’ warning has wormed too effectually into his thoughts to allow him to move. He mustn’t wake Bill. Whatever else happens, he must not wake Bill. He opens his mouth wider and drags at the dark, aware that already the volume of his hauling breath is countering Captain Burrows’ orders, but he cannot persuade the muggy Turkish air into his lungs.

Silence, he reminds himself. Hush. Listen. Hush. The water purls and plashes.

Soon, the steam pinnace towing them towards the enemy slows to a bobbing halt, and the men begin lowering themselves charily into the water: first Edwards, with his always-startled eyes; then Henley, the only one amongst them who stands taller and broader than Francis; next, Farrelly and Whitman, so similar in stance and slight build that they might well be twins; then Hodgson, with his bandy legs and turned-out elbows; followed by Carson, the oldest amongst them, sporting a badger’s streak in his slicked-back hair; and finally Goskirk, who Francis discerns by his woolly farmer’s scent.

The water is not cold. It would feel pleasant, were it not for the fact that it is pouring over the cuffs of their boots, swirling into their bags. It ruffles around their waists and chests, and immediately Francis is aware of the pull of his sodden kit. Burrows was spot on: should a man panic, it would prove all too easy to go under. Francis attributes each inhalation a three beat and concentrates on counting through the unexpected syncopation of his breathing. In, two, three. Out! In, two, three. Out, out! The exhalation he hasn’t yet garnered control of. His lips are trembling. But he is surrounded by water, at least, and it is familiar and soothing and he knows, somewhere beneath his terror, that he is strong when he is held by the tides. That he is the sea urchin his sister named him. That he is pearl oyster and starfish and wolf eel and pinniped and grey reef shark.

Though the guns have stopped now, he senses movement on the beach. He trudges slower, hoping to gain more time to assess whatever aberrant situation he is approaching, and, none wanting to be first ashore, the others slow with him. Now and then, there comes a faint knocking against his shin bones, and Francis grits his teeth and hopes to God there are no skeletons swilling around in the shallows. At their head, Captain Burrows presses on through the softening silt. Occasionally, he snaps around to call them forward with a glare, but the bulge-eyed instruction does little to hurry the men. They are gathering all the information they can. Knowledge, Francis has taught them during their training hikes and their target practice, is as important a weapon as any.

To his surprise, he soon discerns that the beach is only five yards or so deep. Though it arcs some way down the coast, its depth is diminutive indeed. A man might take only ten or twelve strides in one direction before finding himself trapped up against the sheer scrubby hill which rises from the sand into Turk territory. Surely, Francis thinks, Johnnie Turk is defending that hill. He’s heard rumour that the British haven’t yet made it off the beaches at Gallipoli. As such, he had expected them to be vast affairs, freckled with soldiers, not these curled white fingernails, gripping at the lapping sea as they sink under the weight of overcrowding.

Reluctantly, they drip onto dry sand, a clump of deliquescing men. All around are piles of ration boxes, arranged in neat cubes so that Francis feels he has been dropped at the entrance to a labyrinth. And into the maze, Aussies move their ammunition, and barges unload their stores, and bodies are wrapped up and carried into the afterlife. The moon greys the hair of a passing boy who bites an unlit cigarette possessively between his teeth. By fine, cloud-roaming light, Francis contemplates the shroud of a thin figure, laid out in slanting shadow; the white tented roofs of the rowed and mismatched huts; the curved lip of a rowing boat sitting, tilted and abandoned, on the shoreline; the rounded helmets of the men already installed at Gallipoli; the spokes of five enormous gun-wheels, leant against each other and in need of repair; and, further away, the slatted stretch of a narrow jetty into the sea. Everyone is busy. Everything is practised motion. Yet, there is never a noise. Perhaps these soldiers have simply learned to stop opening their mouths to the gruesome tang of decaying flesh and disinfectant. Francis tries clamping his lips closed and relying on his nose, but the effect is not much lessened; his tongue is already ripe with it.

So, this is Anzac, he thinks. It tastes of death.

Down the line, one of the men bends double and vomits over his own boots. Burrows arrives before him forthwith to grasp his shoulders, straighten him up, and nod his head in encouragement.

‘Stand tall,’ he mutters. ‘You’ll get used to it.’

I enlisted in the Royal Garrison Artillery on the 12thDec 1907, being then of the tender age of 15 yearsand 3 months. By mistake the latter was officiallyrecorded as 15 years, 1 month. My rank was ‘boy’, a fretwhich caused me much annoyance since, being a soldier,I considered I was very much a man.

Two

Francis drops on to one knee and, rummaging around in his sodden kit bag, locates and removes his rolled Witney blanket. Likely, the grey wool was gentle over its first owner’s skin, but it has since grown flat and stiff and faded. He bumps a forefinger over its frayed edge. Someone, he supposes, has been boiled out of it. He imagines a courageous lad, a few years his junior perhaps, with a very ordinary name like William – no, Joe – clenching his teeth and wrapping the blanket around a severed foot or a bleeding head in silent determination.

This Joe would have been able to fashion a bandage from just about anything, he decides, having always wanted to be a doctor, and practised earnestly on the knotted legs of his father’s herd of sad-eyed cattle. Or perhaps Joe had wanted to be a veterinary surgeon. Or perhaps wrapping cows’ legs in linen was simply a means of liberating all the kindnesses he possessed but felt he ought to hide.

Francis need not decide now. Thus far, his experience of soldiering has taught him that there will plenty of time for imagining ahead.

In deference to his invented ghost, he spreads the blanket over the gritty sand carefully, to ensure it does not snag on the jaggy shrubs or stones which mark the boundary of the invading forces’ progress – a pitifully narrow curve which lies but nine of Francis’ leggy strides distant from the glimmering shoreline.

It was the measuring of it which had caused him to lose track of Captain Burrows and the others in the writhing darkness. On the off chance, he had stopped and listened for Burrows’ familiar whistle – it was always a snippet of Mozart – but, in truth, he knew the Captain would not be careless enough to break the order for quiet. Francis was a stranger on Anzac Cove, and, since he could not yet think how to make himself useful, he reasoned it was best to grab some sleep and wake rested, ready for action, on the morrow. He felt his way towards a crudely erected hut and propped himself against its facade, thinking to enjoy the last gusts of salt air the retreating tide had to offer.

Some thirty minutes later, he had been disturbed by the combined and hasty movement of those men already dirtied into Gallipoli: towards the huts; towards the cliff face. They were taking cover.

Though he ached from the soles of his feet to the ends of his hair, Francis forced himself mutely upright and followed suit, shouldering his way along the moon-tipped foreshore until he discovered a deep cleft already scooped out of the scrubby cliffside.

Before it now on his hands and knees, he crawls forwards into shadow, stores his kit bag at the back of the narrow cave, then wriggles inside, rolling into his damp blanket as he goes. Within, it is darker yet, and Francis’ eyes dilate desperately, as though in widening they might find something solid to fix on. From his makeshift pillow, he can sight no other living body but the sea, shone under the stout, marled moon. He closes his eyes and hopes that Henley and the others have managed to find similar shelter, for he is certain trouble is approaching. Why else should the beach have emptied so uniformly? Why else would they have been ordered to Gallipoli in the first? Scores of men – Berto and Busty included – have been posted here before him.

It seems that mere moments have passed since that slow falling, ginger-spiced June eve, when he and Henley sat in the shadow of the ship’s funnel to observe the five-hundred Maoris aboard the S.S. Massilia go about their war dance, their teeth gnashing and their tongues thrusting and their eyes popping as they let out their snorts and yells and stamped their feet against the quivering deck. Though it was as exhilarating as watching a streak of tigers snarl together for a hunt, Francis expected Henley – who had proved himself such a bloody consistent fool on Malta – to grow sated and wander away, but he remained as stock still as Francis, fascinated by the foreigners’ rippling chants.

‘Well,’ he said finally, slapping Francis’ thigh with an enormous paw. ‘Haven’t we got something to live up to.’ And the words convinced Francis that, yes, in the absence of Berto or Busty, this was the fellow he’d have beside him when they waded ashore at the Dardanelles.

But now Henley is lost, Francis thinks as he finally submits to sleep. Great, square, burly Henley, with his booming voice and his soft eyes and his reddened knuckles. Gone. As easily as that. Francis had kept him close in the water: closer than young Whitman or poor Drowning Edwards. But he’d discarded him on the sand, like a vest dragged off and thrown to the sky in readiness for a midnight swim. Like the women he had shoved aside at the slightest inducement. Like the sister he had so readily abandoned. Like the friend he had failed and has come here to find.

Anzac, Cruikshank had confirmed when Francis had rushed into his office and demanded he check, had been Berto’s posting. There was no reason to believe he hadn’t made it on ship.

It is only right, though, that Francis approach his first morning in action amongst strangers. It is precisely what he deserves, given how selfishly he has behaved.

In his restless sleep, he touches the place where the damnable lifebelt he was sworn to wear all the way across from Malta smarted his skin: the sore extends above his navel like a hyphen reaching for the second part of himself; the missing component which will make sense of the man Francis Albert House must become.

He starts at the clap of a flattened palm against a proud chest. The hollow thwap of skin against skin is chased by a second, then a third. Pap-pap-pap, goes the beat. Pap-pap-pap. They sound in quick succession. It is not like the Maoris to rush into their dance. It is not like them, Francis realises slowly, because it is not them. The Maoris were bound for Cape Helles, not Anzac.

Francis’ eyelids peel open at the sudden flare of a shell shattering the sky. He jolts upright to the illuminated sight of heels disappearing behind ration boxes; of, further away, the glinting breakers being dulled by the whirring infiltration; then, close to, of the toes of his boots, which stretch beyond the protection of his shallow cave, glowing as if freshly polished for parade; and, when he finally works up the courage to acknowledge them, only a foot apart from his boot soles and looming in towards him, their faces obscured by the inquisitive angle at which they protrude from their necks – two men, waiting, with shovels held aloft.

In the next shell flash, he glimpses the black holes of their eyes.

Francis lifts his arms to display his palms. ‘Hello, fellows,’ he says. ‘What can I do for you?’

But neither man answers him. The shorter of the two simply lifts an erect finger to his invisible lips and exhales.

‘Shush.’

Three

Bill reveals himself with the slanting sweep of first light. From his elevated position, he takes a deep breath, aims his one eye down over the beach, and peppers every inch of the exposed shore with shells.

None moves on Anzac Cove but those grains of sand flung up into a thousand spitting eruptions by Bill’s relentless battering.

Knees tucked up to his chin, Francis stares out from his cave and attempts to tally them. He cannot keep track, and he soon grows frustrated and gives it up, but he knows that if he is to keep his limbs from twitching into movement, he needs to occupy his brain, so he begins instead to plan his letters to Lily, to Ethel, to Ivy, to his mother, to his father.

It ought to be raining, he begins.

How Frederick would scoff at such a sentence. ‘It is or it isn’t, lad,’ he would chide, in his more lucid moments. ‘Speculation is enough to get a man killed.’

It ought to be raining, but…

And there Francis stalls. He cannot get past the opening line. He cannot reconcile the idyllic view with the violent onslaught of shells, for though he is not sheltering from the grey assault of cold sleet on the Plymouth front, it is raining on sun-softened Anzac Cove. It is raining pig iron.

‘Well, there’s your Bill,’ says Farmer, who is hunched now against Francis’ right side, smelling sweetly of damp. His rusted shovel is tucked behind him. To Francis’ left sits Farmer’s companion, who has rested his head against the inside wall of the cave and now snores steadily into the dawn.

‘He’s a measure more forward than I’d imagined,’ Francis replies.

The corners of Farmer’s mouth flirt with a smile.

Already, Francis likes Farmer. Hours previous, when he had woken to find two men looming over him with weapons raised, Francis had supposed himself about to be murdered. But while he’d shuffled desperately around inside his blanket, attempting to extricate his limbs in preparation for lunging forwards and throwing punches for all his worth, Farmer had calmly thrust his shovel into the sand, extended both arms, and said, ‘Won’t you shake a fella’s hand?’

Looking up, Francis saw that he was grinning and, obliging, felt his hand enveloped by two firm, stony palms.

‘Look about you, princess,’ the Australian said.

The near view showed Francis that the Anzacs had dug a trench right up to his blanket and, apparently loathe to disturb him, continued on the other side of his crossed ankles. Evidently, they needed to lay a wire. These two had arrived to complete the portion he was sleeping on.

‘I’m so sorry,’ Francis said, rushing to disentangle himself from his blanket and remove the obstacle. ‘I didn’t realise. Why didn’t somebody wake me?’

The Australian hocked back a glob of catarrh and, putting a finger to one nostril, ejected it from the other with a sudden snort. ‘Didn’t see the need,’ he replied. ‘Who am I to keep a man from his rest?’

Throughout this exchange, the second man remained silent. Francis studied him momentarily.

‘I don’t know what language he speaks,’ the Australian said, thrusting a thumb over his shoulder at his companion, ‘but it ain’t English, we’ve established that much.’

Having now righted himself and dusted the sand from the seat of his shorts, Francis offered his hand again. ‘Francis House,’ he said.

‘Bill Farmer,’ the Australian replied, pumping his arm heartily.

‘Not the Bill?’

Bill Farmer smiled. ‘The Bill?’

Francis shrugged stupidly. ‘Our Captain said we weren’t to wake Bill.’

‘Ah! I should say so!’ Bill Farmer answered. ‘Regardless, you’ll meet him in the morning.’

And already, Francis thinks, he wishes he could rescind the acquaintance.

‘How long will it continue?’ he asks. Jammed as he is between Bill Farmer and his unnamed friend, he is growing stiff and prickly. He longs to walk down to the sea and plunge in. It might loosen his muscles. It might make him feel cleaner. Since the moment he clambered off the Massilia, he has yearned for nothing so much as a good thorough soak in a tin tub. Morning is clawing at the waves now, wild as a hunting cat, made splendid by that same pale gold glint of movement, and Francis wants to revel in the swelling heat of it. Partly, he had joined up for this. He never did deal well with small spaces, and the army had promised him the freedom of mountains or fields, deserts or oceans. As a boy, he’d hungered for all that was open. On those weekends before the House family settled in Plymouth, when they were still gypsying along the coast, his parents would take Francis and his sisters to the beaches and immediately his feet hit new sand, so he would tear off his shoes and run and run until his chest flamed. There was no better sensation than charging away from his family and feeling that gap open up between himself and the deckchairs and the picnic blanket, than savouring the rush of air around his straining body, than hearing the desperate drumming of Lily and Ethel and Ivy’s paces as they tried to catch up to him.

Inevitably, hysterics followed when Ethel or Ivy stumbled and gave up. But Lily never was one to be beaten. Whatever the terrain, however great the distance, Lily would run until she reached him.

He’d played the same game with Berto at Woodlands. It was, he supposed, a test of loyalty. At midnight or just before dawn, he would sneak out of number three room and into the streets, to run between the flares of the streetlamps. Then he would pause in the shadows, listen for the footsteps of the ferocious lad thundering along in his wake, and leap out at him as he passed. Rarely they managed to silence their laughter afterwards, those two innocent boys. They would shove and scuffle the whole way back to their bunks and, when they rolled into their blankets, their stomachs would ache with the simple effort of calming down.

Francis always had felt he needed a brother to cover him in the silent war he and his father were engaged in. In brash little Berto, he knew he’d found one. Though he never could have imagined how much he would ask of him before they even passed out of Woodlands.

‘All day?’ Francis asks, because he has not been listening properly to Bill Farmer and he thinks he must have misheard.

‘On and off,’ Farmer confirms. ‘There’s no work on Anzac Cove after daybreak, that’s for certain. Bill’s a grumpy old fella.’

Francis estimates that he has slept for only a few hours. Likely, Burrows won’t be too angry if he returns now, with the light. He scans the fan of beach visible from inside his cave, but he can pick out no sign of Captain Burrows and the others through the morning’s misty exsufflation. All is achingly unfamiliar. Though it is, at least, more equable than the view he encountered when he arrived those few drenched hours previous. Where men had shifted between the rows of ration boxes, lifting and carrying and depositing, now Francis can see only two pals, cupped in the sand, legs spread before them, their heads lowered as they share out pinches of tobacco.

One is half a foot shorter than the other. Berto and I, he thinks, with a smirk.

‘And don’t imagine you can outfox him,’ Bill Farmer continues. ‘The bastard’ll take your head clean off if he catches you in his sights.’

Francis does not admit to his intention to trudge through the spilling sand, searching any one of the cobbled-together company he dragged off Malta. He is boot-heavy and glad of a reason not to follow it through. He does not want, either, to sit in wait for the rowdy scattering of Bill’s next round – that would do nothing to improve a man’s nerves. What he wants is to retrieve the letter in his breast pocket, unfold the rumpled paper, and let his eyes trail the words down the page again to the scrawled Mrs Lily Carter at its bottom.

But his letter is not for sharing, and he will not open it while there are ready eyes so close by. He resorts to counting, and plods through a three-minute silent spell before realising what is missing.

‘There’s no birdcall,’ he says. On Malta – whether masked by the hissing expulsion of the steam ships, or the unrelenting hubbub of the harbour men, or, at night, the gentle song of the dghaisa men as they sprawled pot-bellied in their vessels, pulled their straw hats down over their faces, and hummed their way into a refrain which rose to haunt the stars – the choked yodelling of the gulls was a constant.

‘Nope,’ Bill Farmer replies. ‘Seems everything can find a way off Anzac Cove but the men.’

Francis wonders if Berto or Busty have managed it.

Last time he’d seen Berto Murley and Busty Leonard together, weeks back now, they were sitting on the harbour wall at Valletta, picking from a leftover plate of cold pastizzi and mussels, and flapping their hands at the swooping gulls. Over the water, dusk skulked, mauve and magenta and minatory. Francis and Berto were teasing Busty about the photograph of his girl he had tacked above his pillow: ‘To watch over us,’ he always said. Jenny-Jane herself was too sweet, too owl-eyed and plum-cheeked, to subject to mockery. But it was imperative they hide the fact that they all took comfort from her motherly plumpness, her honest smile – twenty-year-old Jenny-Jane became their guardian angel long before any of them knew they needed one – and so instead they ribbed Busty. Francis admired Busty’s ability to brush it off. Beyond the quietening quay, and the loafing dghaisa men, and beneath strands of cloud the colour of watermelon flesh which blew across the sky like ribbons, a great, hulking trooper sat, marring the ruffling waves with her dark, cumbrous body and awaiting his dearest pals.

The lucky devils. He’d made jibes at them so that there was laughter to hide his jealousy behind, when what he should have done was stop teasing and insist that they stay there all night and watch the new day begin together. What he should have done was throw his arms around them and hold tight as they said goodbye.

But they were only lads, drunk on weak Maltese lagers and goading each other into a race they knew Busty, with his too-tight belt and puffed cheeks, would lose. They had not yet been to war. When they stood to retire, they left a forgotten plate of pastizzi crumbs and mussel shells on the harbour wall, to await those persistent gulls.

‘How long have you been here, Farmer?’ Francis asks. Rather than look into Bill Farmer’s weather-mapped face, Francis concentrates his attention on the other man’s wrist and the wisps of shining blond hair which curl out from under his sleeve. His boots, Francis has noted, are scuffed and encrusted with lumps of some sort of clay: the lace of one has snapped; the sole of the other is working open. The knees of his trousers are faded. He smells, most pungently, of cigarette smoke and sweat. Francis has already studied Bill Farmer and decided that the man is coming loose. What he needs to know is how long it has taken for Gallipoli to unpick him.

Farmer shrugs. ‘Three, or maybe four… Four weeks.’

Francis turns back to the pair who sit perhaps thirty yards distant, sharing their tobacco. He expects to see two shimmies of smoke rising away from them now, as though from a couple of chimney stacks in the early light, but their heads remain bent over their task, their shoulders slumped.

‘Those two…’ he begins.

Farmer shakes his head. ‘We’ll get them buried after dark.’

‘They’re…’

‘Christ knows what it is that takes them,’ Bill Farmer replies, hardly noticing Francis’ shock. ‘There’s disease here, though, House – that’s for sure. You’ll see as many go without bullet holes in them as with.’

But again, Francis is hardly listening, because he had not realised, and it is worse than seeing a shape wound tight inside a shroud, this… This… The mistake churns his stomach. He’d thought they were pinching tobacco. He’d thought they would share a cigarette then stand, pull up their trousers, and wander away, shoving at each other and joking just as he and Berto had done the morning they arrived at Malta, almost four years since now. He’d thought he would hear their voices, carried on the quiet. It is such a simple thing to expect that to be denied it unbalances Francis, and he pitches a few degrees forwards over his knees, a retch rising in his throat.

Bill Farmer’s arm halts the movement. ‘Not yet,’ he warns.

Francis swallows hard, tasting the bitterness of bile being forced back towards his roiling gut, and when he looks to Bill Farmer again, he finds the corners of the older man’s eyes crinkled in sympathy. His irises are slender loops of sapphire rimming his dilated pupils. They tell Francis of sights he does not want to see.

‘Our orders will arrive with the moon,’ he says, removing his arm by slow degrees. ‘Sit back, House, and look out for the moon. Until then, we wait.’

‘For what?’ Francis asks.

And Bill Farmer, who has hitherto been so garrulous, replies with only a glance of silence.

At 4am on 12th Sept ’11 we marched to Butts Headbehind the 1st Welch Band and boarded the ‘Alligator’,which took us to Hayland across the harbour. Here wewere locked in a 1st class carriage – 10 men and noconveniences – and there we stopped for 12 hours,arriving at Southampton at 6pm. I had again writtento my sister to say at what time I would be passingthrough Britton Ferry, but our special was travellingfast as we approached the station so I got a man tohang on to my heels while I leaned far out of thewindow and waved my handkerchief. The station is ona bend in the line and is flanked by a bridge.Consequently, I only caught a glimpse of my sister andthen had to duck to save my head. The poor girl waswaving at every uniform until she saw me and then shecollapsed. Little did I think of the events that were totake place before I saw her again. It was my birthday(12th Sept ’11) when I waved farewell. Suffice it to sayI was very happy, for I was a full-blown soldier andwas off to see the world. In those days I only asked foraction and excitement, and if wars were to be fought,well, I would be one of the first to volunteer.

Four

Fresh orders arrive with the moon, just as Farmer predicted. Captain Burrows, a Sergeant Patterson, and Corporal House are to gather twenty-five men and take a gun behind the Australians. With Bill satiated by the long day’s shelling, and the moon revealing itself like a sky lantern above the dissolving clouds, Francis has had no difficulty in locating the rest of his company on his second night on Anzac. Indeed, and against Farmer’s best advice, he has taken the opportunity to comb the cove like a fortune hunter, asking after Berto. This high, he has said, holding a flattened hand out in line with his chest. This slim, pointing one erect finger at the heavens. Blue-eyed. Sharp-jawed. Thick-knuckled. Quick-tongued. But, as desperate as he soon becomes, there is little worth in offering more detail. No man here will recognise Berto by his loyalty or his sarcasm. No man will meet the intensity of Francis’ gripped hand as they shake and say, ‘I know him. Saw him yesterday. The dependability was just seeping out of him.’ So many of the things Francis knows about Berto cannot be seen.

At the passing of a third hour, Francis finds himself face-to-face with a lumbering bear of a fellow he has already approached twice, and is forced to give it up. Berto is not on the beach. Unless Francis is able to leave this sorry place at his back, he will have no luck in finding his friend. He returns to his counting, and tallies the minutes he must wait before he discovers where, exactly, they are to follow the Australians.

By true nightfall, the assembled party and two hundred assisting Australians stand braced to begin their labours. They have gathered in a semi-circle, like a rugby team awaiting their match talk, and Francis, positioned before them alongside the Sergeant and the Captain, feels the clammy heat of their bodies as a hand, pushing hard against his chest. They are looking to him and their stare has reduced him to boyhood.

‘The position,’ Captain Burrows announces, ‘is within one hundred and fifty yards of Johnnie Turk. It is not – too – safe.’

And that is all the information they are given before they are hitched up like mules and instructed to sweat and grunt their way forwards. It is soon let slip that they are to drag the cumbrous gun three hundred yards along exposed beach, around a Dead Man’s Corner, and thence uphill until they are able to drop the trail in a gun pit on the cliff edge. Off the beach, then, Francis thinks, nodding encouragement to himself. Off the beach and towards hope. But naturally it is not so easy. The men have barely budged ten yards before they are cursing loudly enough to call every last Turk from his sleep, and Francis cannot blame them. The sand shifts impossibly under their boots. Better the clumpy items were removed so that they could easier grip the ground beneath their feet, but the British Army would not have its men barefooting across Anzac Cove, whatever the benefit – the lessons Francis learnt on Malta assure him of that much.

What ease the steam-engine marches Cruikshank and Dad Rymills forced them through seem in comparison to this. Francis always enjoyed the twenty-milers. They were hot and smoky and difficult. They made his evening sea plunges all the more pleasurable.

Every night from their first in Sliema, Francis had taken to the sea. Often, Berto came with him, but he swam further and faster without his friend, hauling arm over arm in an even front crawl until his lungs were fit to rupture. It was by watery moonlight that he learnt the country, the waves barging at his chin when he stopped to tread water and gather his bearings. He wanted to know the jut and ebb of the coast in the darkness. It would benefit him, he considered, if it came to a fight. He couldn’t understand why that thought hadn’t occurred to the other men, why he wasn’t swimming about in a discovery fleet of pale limbs, but he was glad of it. Offshore, with everything silenced but the deep whirling charge of the Mediterranean Sea and the dull thump of his heart, Francis was nearer home than he ever could be in barracks or out on a march or even practising with his guns.

But the Turkish waters which gleam now to the peripheral left of his vision, he does not know. He has not had the opportunity to explore them. He has not had a chance even to eat since he stepped off the Massilia and, at the thought, he finally recognises the gnawing which has started in his stomach. Scritch-scratch, it seems to go. Scritch-scratch. He must be starving.

‘We could sing our way to the top,’ Francis suggests, as they stand in the shadow of the cliff, fists on hips, and peer questioningly upwards.

‘And what of our orders for quiet?’ an obscured face asks.

Francis speaks in the man’s general direction. ‘We can speak at a whisper,’ he replies. ‘Why can’t we sing at one?’

‘It’s an idea,’ says Farmer. ‘The rhythm would help.’

‘What about ‘Who Were You With Last Night?’’