Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Honno Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

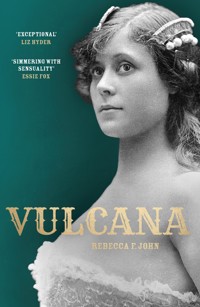

1815. Life is hard for Fannie, working at the factory with only sweet memories of her 'gentleman' and daughter to sustain her. But when she is revealed to be an unmarried mother and dismissed, she is forced to take greater and greater risks to provide for her child. A story of desperation, but also of love and the soaring power of hope. A haunting reimagining of Les Misérables' Fantine.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 132

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

FANNIE

Rebecca F. John

HONNO MODERN FICTION

To all the women who have been silenced

Contents

Prologue

Abandonment

The walk to and from the factory takes her twice daily by the docks: firstly, in the flat, murky pre-dawn, when she dashes towards her half-past-six start, her head low and her ears straining past the groan of incoming ships and their thrown ropes for any sign of danger; and latterly in the approaching clutch of night, when the ladies who holler and moan from the city’s darkest corners sneak around the boatyards and along the jetties to begin shifts of their own.

This morning, the air is cold and Fannie pulls her long coat tightly around her. It is threadbare and mended with two different styles of button: one brass, the other silver. It embarrasses her, but it is the only one she owns, and she has no means of replacing it. She hopes at least to become invisible inside it. In this city, she has learnt, staying unseen is the most reliable way of keeping from trouble.

Winter mists draw the day’s first cargo ships in from the salt-black sea like beckoning hands and Fannie pauses for a moment to watch two vessels drift into view, silvered hulls, then masts, then sails seeming to settle into existence before her eyes. A pair of ghost ships made tangible. The briny stink of shallow tides, just swallowing the mudflats where, come midday, city children will trudge out and lark for treasures. She rests her elbows on the stone balustrade of the narrow bridge, where sometimes her curiosity tempts her to stop, and exhales.

Her breath rises before her in two smoky pillars. Another pair: to match the ships, and their sails, and the two gulls squabbling over a shed feather some steps away. Everywhere she looks, she is confronted by pairs. It causes envy to swell in Fannie. She, too, constitutes one half of an unbreakable pair − at least, so long as the foreman doesn’t find out − but it is not the coupling she had imagined. She had thought they would be three, not two.

One of the ships thuds against the wooden jetty and the sound sets off a scurrying. From every darkened doorway, from the shadows of the ships’ skeletons, from between the sand-held stilts at the dry end of the jetty, the rats come: claws scritching, tails ribboning, fur glistening. They are followed almost immediately by the women. The women have painted over their sicknesses with powder and rouge. They have fastened feathers of mauve and fuchsia and indigo over the thinning patches on their scalps. They have hoisted up their skirts and pulled down their lace-topped camisoles. They are clowns with plumped breasts and poised legs. Their perfume plumes around them, and Fannie turns her head slightly from the cloying, flowery scent which catches on the wind and, stealing between her lips, stings her throat. But still she watches them, parading down the jetty like a chorus of showgirls.

‘Oi, oi, sailors!’ one bellows. Her voice is vulgar and harsh in the early quiet. It matches the heavy clunk of her boots over the wooden slats. She walks with her legs set at a hospitable distance, as though she herself has been to sea and not regained her balance. ‘Come on, chaps. We’ve been waiting on you. Nice to have a friendly welcome, isn’t it, ay?’

On the decks of the ships, the blackened shapes of men, made larger by thick, belted coats and stiff hats, cluster at the bulwarks, haloed by their steaming breath. Leaning over the railings, they whoop and holler as though they are at a racetrack, tickets held in their clenched fists and certain of a winner. To Fannie, they might just as well be leering down at a pack of animals, for all the kindness they will show. She knows too well what cruelty men are capable of.

She watches the women wave their handkerchiefs and tussle with each other for the best position along the jetty, laughing too loudly as they shove and thrust in a manner which persuades their breasts to tremble. Can I interest you in my jellied fruits, sir? Fannie permits herself a gentle smile. Pickled whelks, more like. There is no sweetness to be found under those bodices. And good enough! She thinks it doubtful any of their customers would deserve the taste of sugar.

As the men begin to disembark, she turns and continues her walk. Overhead, the moon is the curve of a swan’s neck, waning into invisibility. Leaving the water at her back, Fannie steps towards the rows of merchants’ buildings she must pass between and, quite by accident, begins trailing a plush blue-grey cat as it struts through slants of shade. She watches it slink and dart, at ease in this imposing place. Set into the columns of the grandest establishments, the moulded heads of lions and horses stare down at passers-by, rendering the buildings as magnificent as the ships and galleons which finance them. They are mostly dark at this hour, save for the occasional lit window behind which some young apprentice labours over his figures. Today, Fannie counts three. She feels a swell of affection for them, these industrious young men she imagines. She, too, prefers to begin the day before the rest of the city. She, too, thrives on the quiet stillness of possibility. She hopes that when each new day dawns, it will be less lonely than the one before. That is all the ambition she holds for herself now. Her every other thought is for another.

The buildings grow smaller as she travels further from the docks. Two streets on, she is stealing past the three-storey townhouses of wealthy families, trying to hold herself so delicately that she moves in silence. Always, she imitates the ballerinas she saw, and was instantly captivated by, on her sole visit to the theatre. When she rose from the dense velvet of her seat, she concentrated on the direction of her every muscle and sinew: first she stretched out her back and found that she had been neglecting perhaps two inches of height; then, after pulling on her coat, she focused on furling her fingers back into a pleasingly dainty position. It was her way of taking control of the body which was beginning to feel so strange to her that dark winter, with its new poking hairs and the bulging flesh she could not seem to strap flat beneath her clothes. She has held to it since. And perhaps it makes a flat, papery creature of her, to stand so straight, to move so carefully, but it is the only way Fannie knows to face the world.

On the doorsteps of each greyed house, the morning newspapers wait, curled neatly inside tied string. Behind their gleaming windowpanes, candlelight gutters as servants lay fires and nursemaids scoop babies from their white, cotton sheets.

One wooden pane has been slid up a little and, through the opened wedge, an infant’s cry blares. Fannie stops, to quiet the even click-click of her boots and to breathe away the sudden clench at her stomach. Still, she responds to that wail for the breast. Even after all this time.

The cat, recognising its home, makes an abrupt right turn, flows up the front steps, and disappears. Fannie straightens up and continues.

Less than ten minutes later, she arrives at the factory. The doors are black and hulking and perhaps fifteen feet high. Fannie pauses under a burning lamp, searching for some excuse to delay taking the last breath of clean air she will enjoy for twelve hours. Her hair has dampened in the mists, and the waves which hang below her bonnet are straggly and dull. She catches a limp ringlet between her fingers and marvels again at how exactly its golden shade had matched her love’s. How surprised she’d been – having supposed they would create a child exactly in their like – to find their new-born daughter’s hair that tone darker. As she climbs the factory steps, Fannie slips off her coat. The formerly royal-blue material has paled unevenly, and she does not want the other women to see its map-like patches. She folds it over her arm, inside out, and, moving purposefully, fails to notice a neat letter slip from her torn interior pocket and glide to the ground.

Her hand is on the door handle when a call issues from behind her.

‘Miss.’ A man’s voice.

She spins around to find one of the delivery men crouched in the gloom the factory casts over the pavements.

‘Yours?’ he asks, proffering an envelope which is pinched between his forefinger and thumb.

Fannie trips back down the steps and, snatching up the envelope, clutches it to her chest. She is suddenly breathless.

The man rises slowly. The smile he had been wearing falls away. He is at least two years younger than Fannie: perhaps nineteen. His light-brown moustache hairs are sparser than those concentrated around his chin. In bending to retrieve her letter, he has wetted one leg of his trousers at the knee. He brushes at it absently.

‘Thank you,’ Fannie manages to say, showing the man a quick smile. ‘I’m sorry. That’s kind of you. I just…’

‘It’s an important letter,’ the man finishes, relaxing again and finally assuming his full height.

‘Yes.’ Fannie nods. ‘It’s an important letter.’

The man extends his hand a second time – for an introductory shake – and opens his mouth, ready to share his name. Fannie does not want to hear it. She does not want to exchange pleasantries with any man. Since her abandonment, she has remained entirely chaste. The factory girls tease her about it, her landlady questions the fact with crossed arms and a raised eyebrow, but Fannie will not be swayed. She has a different purpose now from the one she envisaged before she met her gentleman, when the city was her own whirring carousel, and she has dedicated every ounce of herself to it. She is glad to. It is for love that she works six twelve-hour days a week in the factory, sewing garments for women whose circumstances have fallen more favourably than her own. For love that she eats only a meagre supper before tucking her wages into her pillowcase and, at the end of each week, posting them to the innkeepers she must pay. For love that she rushes to curl into her bedsheets each night and – the portière always drawn back now, for she does not wish to remember how it felt to vanish behind it – dream her way into the shining countryside, where her daughter plays in the fields, and sings, and waits for her.

Needlework

The workroom has always put Fannie in mind of a galley ship. Eight narrow wooden tables run along its considerable length. To one side of each, there is a straight wooden bench, on which the girls might be fortunate to sit undisturbed for an hour before the foreman skulks behind them and questions whether they are working hard enough. The tables are set four feet apart – distant enough so that the girls are not tempted to speak to the rows in front or behind them, but close enough so that the foreman, strutting between them like a full-bellied fox, can reach out his filthy, black-nailed hands to the girls on his left or his right with equal facility. Though the fires are lit on those days when a visit from the mayor is expected, more often the foreman insists that they work with only their lamps to warm them. Through the winter, the girls remain in their coats and bonnets all day and the factory walls run with damp. Drips of condensation drop from the ceiling beams and extinguish the flames of their candles. The girls make fists and try to breathe the feeling back into their red and swollen knuckles. The mayor, who owns the factory, is well-intentioned – they all agree on that, in whispers – but he is too busy to notice that the foreman takes pleasure in their discomfort. The promise of its easing is a commodity he attempts to trade – ‘for the right price,’ he suggests, leering. The gaps between his teeth are grouted with yellowed tobacco residue; his words are met with winces. Fannie does not know how many of the girls have submitted to his advances, but judging by the angry glances which pass between the foreman and the jet-haired supervisor, she suspects that at least one has, and that the outcome was at best disappointing.

As she unfolds the first garment she will work on and flattens it over the table, Fannie plans the sentences she will dictate to the letter-writer later that evening, ready to be sent into the countryside, to the couple she has trusted with her whole heart.

I can pay. Anything, so that you might purchase the medicine she needs. I just need a little time. A week, if you please. Withina week, I will find the money. I beg you: do not stopadministering the medicine…