Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Honno Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

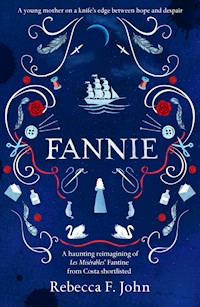

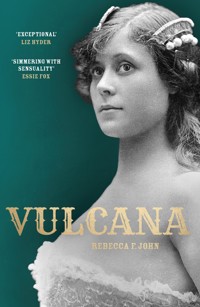

'Telling the frankly jaw-dropping story of real life Victorian strongwoman Vulcana, it held me spellbound. A master storyteller at her absolute peak.' Liz Hyder On a winter's night in 1892, Kate Williams, the daughter of a Baptist Minister, leaves Abergavenny and sets out for London with a wild plan: she is going to become a strongwoman. But it is not only her ambition she is chasing. William Roberts, the leader of a music hall troupe, has captured her imagination and her heart. In London, William reinvents Kate as 'Vulcana – Most Beautiful Woman on Earth', and himself 'Atlas'. Soon they are performing in Britain, France, Australia and Algiers. But as Vulcana's star rises, Altas' fades, and Kate finds herself holding together a troupe of performers and a family. Kate is a woman driven by love – for William, her children, performing and for life. Can she find a way to be a voice for women and true to herself? 'Beautifully written, thought-provoking & a touching love story.' Tracy Rees 'All the glamour and grit of music halls. A truly empathetic portrayal of a brave, independent young woman.' Essie Fox

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 564

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

VULCANA

A Novel

Rebecca F. John

HONNO MODERN FICTION

To Kate Williams, strongwoman, whose story inspired me.

For Jane Vanderstay Hunt, who shared Vulcana with me.

In memory of Andrew Bullock, a strong man.

Contents

Opening Act

Abergavenny, Wales 1892FLIGHT

The rain is a scuttling creature – moody and glancing and out to do harm. From the scant shelter of a locked and darkened doorway, Kate Williams watches it cross at a quick diagonal under the street lamps, then hasten away down Tudor Street on the wind like a murmuration of silver starlings. Where it gathers into puddles, their surfaces flecked and rippled by the insistent downpour, it soon spills over and escapes to the runnels to rush away. Even the rain does not wish to stay in Abergavenny.

Above Kate’s head, a stream of raindrops collects in the broken end of a drainpipe, and proceeds to drip, with percussive regularity, onto the dome of her cranium. She has come to know herself in these terms since meeting William. Not scientifically, exactly, but … specifically. Intimately. Cranium – twenty-one inches. Neck – twelve inches and one eighth. Neck, flexed – fourteen inches. Her body means something now. She is learning what it might be capable of.

Across the street, the gymnasium hunches in the darkness. The windows, black, reflect only the movement of the storm. Kate knows that the door is bolted, and she resists the urge to run through the rain and put her hand to the stubborn catch of the handle and try to twist it free. She does not want to know what it feels like – the fact that William has gone. William, Mabel, Seth, Anna. Gone, without her. She takes a deep, shuddering in-breath, then exhales through her nose and watches her fury rise into fog. The air tastes of dampened woodsmoke, battered down from the chimney stacks by the weather to linger over the pavements. It is cigar-bitter. Choking. It tastes like home.

She tightens her arms around her waist – trim but sturdy at twenty-five inches – in a feeble effort to counter the cold. Her father will be sitting before the fire in their living room now, ankles crossed on the footstool, pipe clamped between his lips as he scribbles his next sermon on the back of an old hymn sheet. Her mother will be knitting without needing to count the stitches, and watching her husband as intently as he, in turn, squints over his penmanship. She will be talking about some friend or other – Aneira will arrange the flowers, and Nerys will offer the tea – and her husband will be grunting in response. The reverend’s wife’s voice is the soothing background noise to which he works, but does not listen.

Kate supposes neither one of them will miss her until morning. Neither would dare open their daughter’s closed bedroom door. They are far too frightened of the mysteries that thick wooden divide conceals.

This Kate – who, at sixteen, has hips and an ample bust and ideas – is not the rose-cheeked baby they had thought to bring into the world. This Kate, who wraps her slender hands around barbells more successfully than she ever has a fiddly needle and cotton… This Kate, who already men grin at and posture for… This Kate, who has felt her pulse quicken and the unexplored place between her legs throb at the sight of William Roberts straining under two-hundred-and-fifty cast-iron pounds of bar and weights… This Kate is entirely unknown to Robert and Eleanor Williams.

And so, Kate reasons, she is at liberty to do exactly as she pleases, whatever Reverend Williams might have to say about appearing before the judgement seat of Christ. If her parents have no knowledge of her, no understanding of her desires, no interest in her talents whatsoever, why should she stay here and disappear under their indifference? Particularly when they have Margaret and young Eleanor and little William – who are all far more obedient than she – to find pleasure in.

When Kate’s William – as she has secretly come to think of him – looks at her, she is brighter than she ever has been under God’s gaze. Through his eyes, she is a pearl, gleaming from the cupped bed of an oyster shell. And she cannot give that up.

It has not escaped her attention that his name is an inversion of her father’s: William Roberts; Robert Williams. Indeed, the fact has only served to persuade her that what she is doing is right. Everything she has in Abergavenny is the exact opposite of what she needs. She cannot tolerate another morning of sitting to a tea-and-brown-bread breakfast around their long oak dining table and watching her mother, her brother, her sisters simpering over her father’s pronouncements. She cannot bear to see him peacocking around before his congregation, as though he is treading the London boards rather than creaking over the rotting floor of a dank old church in the Welsh hills. If Reverend Williams had wanted to be a star, she thinks, he should have gone out into the world and made it happen.

In less frustrated moments, Kate feels sorry for him. Her father is a great speaker. He might have made a name for himself somewhere, if only he’d been braver.

But tonight, Kate’s frustration is a live thing. She can feel it in her stomach – a coiled rope, braided from strands of hurt and desperation and ambition and lust, and cast into a wild sea to thrash and dance. It is as though there is a rough-handed fisherman at one end and a writhing finned creature at the other, and she, the rope, is being pulled in both directions. It is the creature that will win out, she knows, eager as it is to break free and go chasing after William without the first inkling of a plan. And in truth, she does not want to stop it. She only hopes to slow it long enough to make the proper arrangements.

Though she has never acted on any such impulse before – never felt it for anyone other – she is wise enough to recognise it for what it is. She wants William Roberts as much as she covets the life he leads with the troupe. She wants him to hold her too hard; she wants to learn how his lips taste; she wants to feel herself pinned under his muscled weight; she wants to bite into him until she draws blood and can swallow the pulsing red heat of him. The remembered scent of his skin as he stood over her supporting the bar – cigarette smoke, iron, sweet talcum, sweat – is enough to thrust her into action, and, for want of anything better to do, she marches across the street and pounds a fist against the gymnasium door. She needs the indulgence of exerting her force against something solid, and the satisfaction of hearing its empty thud. She needs William.

Held in her left hand is the travelling case she had packed in preparation. She’d been planning to leave with him for weeks. It was going to be a surprise. She has timed it badly.

She hammers the door until she is breathless, then she spins about and strides away, a lone silhouette in the sleeping streets, her falling heels echoing off the mountains which sulk over the little town.

Kate Williams and William Roberts, she resolves, pushing her chin higher in defiance, though there is no one to see her, no one to counter her intentions. That’s how it will be. The two of them. She is going to convince that man to show her the world.

Intermission

London, 1939

A low, insistent hum bothers her ear as she takes the long way – she has to keep her fitness up somehow through these slow days – across her city towards the letterbox. A bee, perhaps, she thinks, though the weather is wrong for it. She swats a knotted hand at the close, dank air; the noise does not subside. She swats again, for good measure, but she refuses to be irritated by it. London is as flat and grey as a bad mood today, and she is not inclined to join in with it. She is not about to start submitting to despondency now. What a waste that would be, after so much fighting for this life she wanted.

She looks across the street for the bright red pillar of the letterbox and, spotting its happy colour through the smog, pats the pocket containing the letter for Nora. Safe. The hum grows louder and she swats at the air for a third time. Indeed, she swats at it twice more before she recognises the sound: not the flight of an insect at all, but the grumble of an engine. A cab. Oh, how she had preferred them with horses. Where, she wonders, have all the horses gone? That such an elegant creature could be replaced by a bloody Austin High Lot… Beastly vehicles. So square and graceless. And always travelling too fast, like so much else these days. The declaration of another ugly war seems to have ground the country into a new gear, and she wants none of it. She has only just managed to slow down.

But she needs to slow down further, it seems, because she is breathless. There is a tightness in her chest that she would have thought impossible once. To be left breathless by a simple walk! And yet, here is the evidence of it – she is wheezing. Without checking her surroundings, she stops and closes her eyes, to concentrate not on the pain in her lungs or the fading blur of the world around her, but on the sounds, the smells. Clutches of delphiniums are pushing through the park railings to her right, and she is just able to catch their sweet, unobtrusive scent against the dirt and smut of London. Beautiful, she thinks. The small things. Slow down… But the cab does not. And she is not looking.

1892

Act One

1.

London, England 1892THE FOG

London, she soon discovers, is filthy. She steps out of Paddington Station near mid-day, creased and smoky and itchy with tiredness, thinking to escape the blackened smut of the steam engines and breathe again, only to find that the air without is thicker than the air within. The city is a pale blear of fog.

Here and there, if she squints hard enough, the dark squares of window frames or doorways become visible. She discerns an uneven row of brown chimney pots, thrusting into the stone-pale sky, only when a raucous pair of corvids flap down to settle on them. She seeks out the curves and edges of nearby buildings, in hopes of studying the enormity of this place through its smallest parts, and eventually, after much concentration, a pitch of black slate roof is revealed, faded to grey; a pane of glass glints and then is lost; a line of rain gutter runs across nothingness like a railway track to the clouds. But these are only abstractions. They have the spiritless effect of a badly executed watercolour rather than the bold pride of an oil painting – which is closer to what she had expected of the city.

Kate can barely view the opposite side of the street from where she stands, her nostrils already blackened, her travelling case clutched between the aching fingers of her right hand, and the brim of the small felt sailor hat she borrowed from Margaret’s closet pinched between the trembling fingers of her left. She has to hold firm to something. Though she hasn’t stepped properly into it yet, she is already breathless with London.

‘It’s a bad one today,’ says a plump lady who has stopped alongside Kate to set down her bags and rearrange the ribbons of her bonnet. The lady grimaces as she feels about for the bow, unloops it, and begins again, tipping the bonnet backwards and forwards half an inch until it sits comfortably. She gives off the soft scent of flour, and her blue eyes are small and kind, and suddenly Kate wants to hug her. She bites her lip against the temptation.

‘Excuse me,’ she says, ‘but a bad what?’

‘The fog,’ says the lady, giving her head a little shake to ensure that the bonnet is properly secured. Satisfied, she bends to gather her bags. ‘I’d keep that case close if I were you. You know what it’s like in the fog – unwelcome hands all about. Here. Bring it up in front of you, like this…’ She hoists her own bags up against her chest, as one might a swaddled baby. ‘Wrap your arms tight around it, and keep your head up as you go. It’s always worked for me.’ The lady gives a friendly wink and walks away. Kate hardly knows what she is protecting – the travelling case or her own body – but, all the same, she does as she has been told as she prepares to set off. She does not yet know how to move through this strange new city, and she is grateful for the instruction.

With both hands occupied, however, she soon finds herself in want of a third – so that she might hold a freshly laundered kerchief to her nose, for the smell is brutal. Though she clamps her lips tightly shut, she can already taste it. Smoke, yes – gritty with coal dust, even here. And beneath that, a stench like wet wool drying over a fire. And beneath that again, passing traces of manure, stale beer, and something as full and briny as a caught fish.

She pictures the neat white kerchief she has folded into her travelling case, regrets not placing it in a pocket, and begins to stride away from the station. She has only one destination in mind. She has kept it on her tongue all the way from Abergavenny, so that she might ask the way.

York Road, please, she will say. Battersea.

She believes that the straightness of her posture and the breadth of her shoulders will dissuade anyone with funny ideas from misdirecting her. Though she stands only averagely tall at five feet and four inches, and appears nothing more than shapely in her blouse, hooped skirt, and jacket, she knows herself to be strong. Exceptionally so. She had been only fourteen when William had invited her to appear at the Pontypool fete as a strongwoman. A year younger still when she had taken hold of that runaway horse’s rope and bodily hauled the skittish mare to a stop in the street – they wrote about that in the papers. She is of the steady opinion that, should any person with unwelcome hands sneak up on her in the fog, she will be more than able to fight them off.

Summoning up a pinch more bravery, she lowers her travelling case back to her side, where it can swing more conveniently, steps into the white mystery of Praed Street, and begins the walk towards Battersea, where she will find her new life.

That afternoon, Kate wanders for miles. She thinks that perhaps she has never encountered so many different kinds of people. For a time, she walks through a large park – Hyde Park, the signs tell her – kept in gentle company by swaying sweet chestnuts and whispering hornbeams. But even amongst the trees, she does not find silence. Walkers pass in urgent conversation, and carriage drivers murmur comfort to already placid horses, and geese gabble like washerwomen at the water’s edge. London has not yet revealed its bold strokes of oily colour, but it is growing brighter. On the countless streets she turns into and out of and into again, she dodges apple women and flower sellers and match hawkers; a fish porter, with a basket balanced expertly on his bowler-hatted head; plagues of little urchins, scrabbling shoeless and frozen for the congealed scraps fallen from the fishmonger’s table; barrow boys cupping their hands over their mouths and blowing their blue hands pink again; a frightened horse, with rolling eyes and high hooves, being trotted through the crowds on a tat of rope; men in black top hats and frock coats lifting their feet to the quick rags of the hunchbacked shoe shiners; university smarts with good clothes worn purposely grubby and lofty airs; scoundrels leaning against lamp posts awaiting an easy theft; a young girl flogging a stack of magazines higher than herself. And all of them cough-coughing against the gag of the insistent smog.

At breathless intervals, she catches sight of her father, striding through the crowd towards her, his cassock flapping wildly. She hears his voice, intoning the lessons of Matthew 25:46: Then they will go away to eternal punishment, but the righteous to eternal life. Words which ran through their home like stitches through fabric echo in her mind. Each apparition resolves itself, eventually, into a passing stranger.

Kate wants to stop and ask them questions, to strike up conversations as she would at home, to learn more about these people’s lives. Each one of them intrigues her, whether on account of the tone of their skin, or the contents of their barrow, or the unfamiliar sounds which flick from their tongues. But all she says is, ‘York Road, please? Battersea?’

Until, some time near dusk, she finds herself standing on Battersea Bridge, her palms to the cold, cast-iron balustrade, staring down into the dark murk and lap of the Thames.

At her back, carriages rattle from one bank of the river to the other. The gas lamps which dot the length of the bridge have been lit and leave little orbs of luminosity on the water. Cold mists churn around the submerged granite piers. It would be beautiful, were it not for the inescapable stink of mouldering seaweed and shit. Kate thinks that perhaps all the sewage in the city is dumped into the river, to slosh away into the sea. Not wishing to watch it go, she continues across into Battersea. She had left Abergavenny with nothing much more than the name and location of the theatre where William and his troupe are due to perform their first London show: The Washington Music Hall and Theatre of Varieties.

It had sounded so impossibly romantic that she had known she must see it. She longed to stand on its grand stage, to drink in its hubbub and glamour, to listen to its stories without being able to begin imagining what they might consist of. She is sorry now – as she coaxes her aching feet through yet another cobbled mile – that she hadn’t simply told William she would come with him. Perhaps some small part of her had feared that he would not allow it. Your parents, he would have argued. Your father. His gentlemanly ways would not have permitted him to say otherwise. Better perhaps, then, that she has denied him the choice. He’ll be happy when she gets there. He will – whether he can show it or not. But there is a tight pulsing sensation worrying her neck and jaw which reminds her that she still doesn’t feel sure he will not turn her away.

She plays through the nightmare of it, to prepare herself. Go home, you silly girl, he’ll say. Why would we want you here? And then he’ll slam a door in her panicked face and, with a muted laugh, shatter her heart.

Mercifully, these are not the words he does choose when, a couple of hours later, he finds her sitting on top of her travelling case on the pavement outside The Washington Music Hall and Theatre of Varieties, bone-cold and exhausted.

All he says is, ‘Kate,’ and Kate, her forehead resting on her knees, does not need to lift her head to know that it is him. She has never before heard her name spoken with equal measures of tenderness and excitement. The sound causes her stomach to clench, and she knows then that she will have him. She must. She cannot do without him. When the woman saw the fruit of the tree she took some and ate it… And when at length she looks up and sees his expression, caught somewhere between worry and joy, and his eyes, soft but sparking, and his hand, already reaching tentatively out for her, she thinks that perhaps, just perhaps, he cannot do without her either.

‘It’s bitter,’ William says, stepping nearer and offering Kate his hand more firmly. She takes it, though she does not need the assistance, and pulls herself up. His warm skin causes hers to rise into gooseflesh, and she draws herself as close to him as she dares, yearning to catch a hint of cigarette-smoke breath through the oiled whiskers of his moustache, or to feel the shifting of his muscles beneath his swarthy skin. William is not tall – he stands only a hand’s span taller than Kate – but he is powerful. His chest is forever expanded. His forearms bulge under his shirtsleeves. His thighs bow outwards, strengthened into the shape of a chimpanzee’s. William bristles with an alertness that Kate senses but cannot define. He might always be ready to defend himself; he might always be ready to attack.

‘How did you get here?’ As he says the words, he glances about himself as though seeing the theatre, the street, the city for the first time. Kate, too, is able to consider her surroundings in closer detail, now that William is here, and she is safe, and she can begin to unclench. The theatre’s upper two storeys have a clean brick façade, crowned by a row of stone parapets; the entire ground floor boasts a colonnaded entrance way, with hanging gas lamps and shuttered doors. Posters positioned beneath the gas lamps inform her that performances at The Washington proceed ‘twice nightly’. She does not know, and does not question, why the building is closed now. Everything seems closed up tonight: the theatre, the row of black-windowed shops opposite, her own good sense.

‘Kate?’ he says again.

She remembers herself and engages her stomach muscles, straightening up from her core, as she has been taught. She lengthens her neck and lifts her chin.

‘By train, of course,’ she says, allowing herself a small smile. ‘I knew you would come to scout the place out.’ Then, after a short pause. ‘Do you think I’m so useless that I can’t step onto a train by myself?’

William laughs – a short, surprised sound. ‘No, I don’t. I think you’re capable of just about anything, Kate Williams.’

‘Good.’ She is growing haughty now. Her confidence always swells when she is in William’s presence. She cocks her head in what she considers to be a playful but determined way. ‘Because I have come to be your strongwoman. Star act only, mind. I won’t be second on the bill.’

William’s eyebrows rise above his brilliant green eyes. ‘Is that so?’

‘It is very much so.’ Kate brushes down her skirts, which already feel grimy to the touch, then bends to lift her travelling case. It has grown heavier by the hour, as though her fear had crept in through the seams to weigh it down. ‘Now, where are our rooms? It’s been a long day.’

She imagines how it might be, if she and William were to share a room to themselves, and her stomach jumps at the thought.

William hooks his arm and offers it to Kate. ‘I’ll show you to the rooms,’ he says, ‘on one condition.’

‘I’m sure I’ll agree to it.’

‘Wonderful. I’ll find some papers and an envelope and you can write straight away to your parents.’

A whine rises in Kate’s throat, but she manages to quell it.

‘All right,’ she agrees. ‘But just a short note.’ She turns her eyes on him, all flutter and lashes. Her eyes – large and round and a startling rich cinnamon brown – are her greatest beauty. She does not know how to bargain with them yet, not flawlessly, but she is learning.

‘All right,’ William agrees, and finally she loops her arm through his and their steps fall together and Kate knows without doubt that walking down a strange London street with a man as wise and sophisticated as William Roberts is exactly where she ought to be. He really is going to show her the world, and she wants to explore it all.

‘I can’t see where we’re going,’ Kate says, pressing herself closer to William, inhaling the clean cotton scent of his pressed grey suit. Ahead, the ashy fog waits to enshroud them.

‘No. Neither can I,’ he replies. ‘It’s exciting, isn’t it?’

Kate’s face opens into a wide, silly smile, but she does not lower her head to hide it. She is quite happy for William to see her exactly as she is.

‘Yes,’ she says. ‘It is exciting.’

2.

London, England 1892AWAKENING

The next day dawns cold and splendent, and Kate wakes between clean white bedsheets, her lids heavy and a deep ache spreading across her lower back. She opens her eyes a dash, is confronted by stark morning light, and closes them again to shut out the sting of it. She straightens her legs over the cotton undersheet, then arches her spine. She is stripped to her petticoat, but feels warm enough, snugged in as she is. Pulling her arms free, she stretches them above her head until she feels something inside her pop, then slackens again in relief, her exposed skin already beginning to turn chill. Somewhere nearby, voices converse at a murmur, but she does not reach for the words: she does not want them yet. There is a drifting scent of coffee, and perhaps, though less pungent, sugared tea. Kate feels she might be in Paris. Or Vienna. Or on the other side of the globe entirely, waking to breakfast she will take on a balcony overlooking cliffs and the crashing sea. She sees herself opening a book as she bites daintily into a croissant fresh from the oven, and smiles at the presumption of the idea. Kate Williams, from Abergavenny! But, how beautifully foreign it feels, to be here and not staring out of her parents’ kitchen window at a rainy rampart of fields and trees and flocked sheep.

Escape, she thinks, feels opulent.

Opulence was not permitted under Reverend Williams’ roof. Prayer, charity, and study left no space for indulgences, however much she might have begged for a Sunday in the sunshine instead of watching it through a stained-glass panel. Her father’s voice chimes through her mind again: do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return, and your reward will be great, and you will be sons of the Most High, Luke 6:35.

She stretches again, gives a groan. The sons of the Most High. What, then, of the daughters? Outside the hotel window, the city is a muted collection of unfamiliar sounds: the grind and clop of horse-drawn omnibuses; the thud and clatter of carts being loaded or unloaded; the prattling of so many people along the pavements; the shouts of disgruntlement or greeting; the ringing of bells above shop doors as customers swing through. In Abergavenny, she would wake only to the pot-and-steam sounds of her mother at the stove.

Finally, she opens her eyes again, slanting her hand over her eyebrows to shield them from the glare, and lifts her head and shoulders slightly. When William had snuck her into the room last night, she had seen nothing of it but shadows. Now, she discerns that the walls and ceiling are painted white. At the window, a pair of mustard-yellow flowered curtains hang, already pulled open and smartly pleated into their tiebacks. There are two more single-width beds, a heavy mahogany wardrobe, and, on the far side of the room, a small round table at which two women sit drinking tea from small china cups.

‘You’re finally awake, then?’ says the woman on the right. She is already neat in a high-necked cream shirtwaist and blue tweed skirt. She has not yet laced on her boots, and a stockinged toe peeps from under her hem. Her deep auburn hair falls loose over her shoulders. She is half put together and easy with it: Mabel. In the other chair – shorter, plumper, and fair-haired – Anna plucks purple grapes from a stalk and sucks them between lips pursed with amusement.

Mabel grins into another sip of her tea, swallows it slowly. ‘We said you’d come, you know.’

‘You did?’ Kate asks, and her voice is rough with thirst. She longs to share the tea, but it feels rude to go over and help herself when she has descended on Mabel and Anna’s room unannounced.

Mabel indicates the furniture with a sweep of her head. ‘Three beds and two of us to share. I think William was expecting you to leave home with us.’

‘I intended to,’ Kate answers, sitting up fully and arranging the sheets modestly at her hips. ‘I must have just missed you.’

‘Well,’ Anna puts in. ‘You’re here now.’

‘Is that all right?’

In response, Anna pours from the teapot into a third china cup, adds a splash of milk, then brings it across to Kate, who accepts it from her sitting position as if she is a grand lady. Part of her flushes for the shame of allowing Anna to wait on her; another part of her enjoys it.

‘Of course. Why shouldn’t it be?’

Kate can conjure a thousand reasons: because she couldn’t imagine two women in their middle twenties would want a sixteen-year-old trailing around the country after them like an annoying younger sister; because Kate has made it known that she intends to install herself as the troupe’s star act; because she has already proven herself stronger than both Mabel and Anna in weightlifting contests across Wales, Bath, and Bristol; because she represents, doesn’t she, a threat to how much of William’s attentions they might receive. But then again, perhaps they do not crave his attentions as she does. Kate has never known them to flirt or fuss over him. It would seem that theirs is the business relationship it ought to be. After all, Mabel, Anna, each of the women who has passed through the troupe, know as well as Kate does that William is married.

Kate drains her tea to avoid offering Anna an answer. It is tepid and sweet and a godsend.

‘That’s that, then,’ Mabel announces. ‘Now get dressed. We’re going out.’

‘Won’t you be wanted at rehearsals?’ She is careful not to say ‘we’.

‘Later,’ Anna confirms. ‘First, we have to go to the river.’

‘Why?’

Anna’s face lights with child-like excitement. Her smooth round cheeks pink. ‘They say it’s freezing over.’

‘It’s not cold enough,’ Kate says.

‘Open the window,’ Mabel replies. ‘You might disagree. They say it’s always warmer when the fog is down, but now that it’s cleared…’

Kate needs no further persuasion. Throwing back the sheets, she rushes over to the window. Without a thought for who might look in and see her exposed in her slip, she grasps the handle and pulls the thin-framed pane back into the room. The cold thumps her straight in the stomach and causes her to gasp. Laughing, she turns back to Mabel and Anna.

‘Do you think it will snow?’

‘No,’ Mabel replies. ‘We’re too close to the water. But hurry and get dressed and you can check for yourself. Don’t forget your gloves.’

Kate skips over to the wardrobe, beside which she had abandoned her travelling case in the dark hours before, and flips open the clasps. As she rifles through it for her gloves, she tosses blouses, petties, and stockings over her head to alight in heaps on her unmade bed.

‘Gloves, gloves, gloves,’ she mutters to herself as she searches.

‘The Thames isn’t going anywhere,’ Anna laughs, eyeing the mounting pile of clothes. ‘No need to wreck the place.’

Kate pays her no heed. Delight – at finding herself here, at the memory of William’s hand over hers as they walked back from the theatre last night, at the brilliantly cold air swooping in through the window – is welling up inside her and she needs to be outside, under the sky, where she can run or spin or dance. Now that she has found the bravery to walk away from home, she feels that she might never stop moving.

‘Gloves!’ she squeals, lifting them above her head like a trophy.

Within fifteen minutes, Kate has gathered her hair up into its pins, pressed on her sailor hat, and the three women are laughing down the hotel stairs towards the start of the day.

They reach the river before nine o’clock. Though the sun is still low over the city, it throws out its light in sturdy beams, hitting the water at a shallow diagonal and illuminating the cold mists which steal over its surface. Kate can hardly believe how far the temperature has plunged. Inside her gloves, her knuckles are stiff with it. The three women’s exhaled breath makes steam engines of them. The ground beneath their boots glints with frost, and Kate chooses not to look from the pavement and into the street itself, where mud gathers into furrows and skets off the wheels of passing carts and bicycles. Perhaps making the most of London, she thinks, will mean deciding where best to place one’s eyes.

With no real direction in mind, the three friends gravitate towards the busiest stretch of the river. There, a troop of industrial ships – imposing black funnels and empty slicked decks – brood silently. Around their hulls, the water has already thickened and stilled to ice. Further out, in the middle of the river, a darker stream continues to flow, and along this narrow passageway, smaller wooden boats manoeuvre, though it is evident from the warning shouts of the sailors that the going is not easy.

‘How can it have happened so quickly?’ Kate wonders.

In answer, Anna and Mabel only stare down at the unmoving whiteness. None of them knows the patterns and peculiarities of this place yet, least of all Kate, and she is as thrilled by the lack of knowledge as she is scared.

‘Look over there,’ Mabel says, pointing across the river, to where three dark figures sit crouched on the bank, lacing themselves into three pairs of large black boots. ‘They’re going to try skating on it.’

‘They’re not!’ Anna breathes.

‘They are!’ Mabel laughs. ‘It’s going to be disastrous, surely.’

The women lean as far over the stone balustrade as they dare to watch. The three small figures help each other to rise, then wobble tentatively onto the ice. They take a moment to gain their balance, heads bent in concentration as they test the blades of their skates with small forward pushes. They slow to a stop, adjust their coats, begin again. And it is a matter of minutes only before they are gliding over the river, hands tucked behind their backs as though they are champions of the pursuit.

As they come nearer, Mabel pushes her head forward further still and squints.

‘They’re police!’ she shrieks.

‘No,’ Kate says.

‘They bloody are,’ Mabel laughs. ‘Look at their helmets, and their matching coats. They’re skating police. What a thing.’

‘They must be going out to check on the ships,’ Anna suggests.

‘They’re having a good time doing it, too,’ Mabel replies, as the three men reach the last of the established ice and, gathering speed, skirt along the edge of the few feet of lapping water which still separates one solid bank of the river from the other. They speed out of sight like an arrow of black birds, launching themselves into flight.

‘I want to try it,’ Kate says. Never in her life has she skated over ice.

‘We don’t have any blades,’ Anna replies.

‘Not today. But one day.’ She closes her eyes and pictures what it would be like, to rush along with only water to hold you up, and feel yourself so very, very free.

She opens her eyes again when there comes a disturbance to her right side: clutches of small children are clambering over the balustrades and dropping down onto the ice below with hard thuds.

‘You’ll fall through,’ Mabel calls, ‘thumping down like that.’

But the children only glance back and smile toothlessly, then take off running and sliding, their tatty clothes hardly sufficient to keep them warm even on a balmy day. Some wear flat caps; others go bare-headed. Some possess coats – either too big or too small and never just right – while others have on only dresses and shawls. Inside her thick coat and woollen gloves, Kate shivers for them. Their fun will keep them warm, she supposes, as they scatter over the ice, skipping with arms linked, or shoving each other over, or lowering themselves onto their bottoms to skid along all the faster. Based on their stature, Kate would suppose them no more than six years of age, but the flint look in their eyes persuades her that some might be closer to ten or twelve. Their whoops and cackles ring out, clear as chapel hymns on the calm air.

Two smaller children remain on the pavement beside Kate, staring wistfully out through the balustrades they cannot reach to climb over. They are perhaps four years old. They retain the round-bellied look of toddlers. Their eyes are big with sadness at missing out, and yet Kate cannot bring herself to lift them up and drop them down to join the others; it really is too dangerous. Instead, she invents a game.

‘Come,’ she says, beckoning to the grubby pair. They shuffle closer to her with the willingness of hungry kittens. ‘Let’s play trains.’ And angling her arms at her sides like rods and using her elbows as crankpins, she begins to chug along the pavement, jerking her hands through a rough oval arc and pouting her lips to push out breathy white puffs. Choo-choo-choo-choo, she goes. Choo-choo-choo-choo. And the children, giggling, join in behind – the carriages to her engine.

Anna and Mabel, backs leaning against the balustrade, watch as Kate and her orphan playmates mark a wide turn around a nearby fruit hawker before chugging back in their direction. Kate sends them a wink as she woo-woos past and deposits the children on the spot where she found them.

‘Your friends will be back soon, I’m sure,’ she says. ‘Now why don’t you carry on down that way, to keep warm.’

The children, grinning, keep up their choo-chooing and continue the train’s imaginary journey along the pavement. Kate laughs to see them go – arms orbiting, breath steaming – and ignores the stab of guilt she feels at having left her brother and sisters behind. As a small girl, she had enjoyed having siblings in a way her school friends had not. They had laughed and teased together, the Williams children. They had bent their heads over secrets that must be kept from their parents. They had invented games with rules they vowed not to share, purely for the joy of possessing something which was only theirs. And when they had grown too old for such simple pleasures and carelessly discarded them, Kate had told herself that she would one day have children of her own, and that with them she could recreate what had been lost.

Soon, the train-engine pair are lost amongst the crowds which assemble to watch the skating policemen, and the frolicking children, and the locked-in ships, and the little boats which cluster to clog the last moving rivulet of the Thames. People line the river and point out this sailor or that struggling vessel. Herring gulls swoop and caw overhead. Pigeons flap around ankles, pecking up dropped nuts and bits of detritus without distinction. Passing dogs prance, exhilarated and confused by the chill at their paws. Of a sudden, it feels as though the entire city is celebrating, and so different is this from the impression Kate had yesterday that she could roar with relief.

This is it. This is the place she imagined. Here, with a stage and an audience, she might reinvent herself. Here, she might be seen.

‘I was wondering…’ she says, turning back to Mabel and Anna. ‘Would you show me inside the theatre?’

3.

London, England 1892THE TROUPE

Gathered as they are by twelve noon under the high ceiling of The Washington Music Hall, William Roberts’ troupe of strongpersons seems a diminutive group indeed.

In their day clothes, Kate, Anna, and even Mabel – despite her height – appear as might any group of women out for a day about the city. William, who stands on stage speaking to the theatre manager, seems no more impressive, dressed in the same grey suit he wore the night before and standing a head shorter than the man to his right. There are two more men engaged in the troupe: Abraham, ‘Named for the president,’ he says, winking and clicking his fingers into a point, though Kate is convinced the accent is affected for its exoticism and the name an invention; and Seth, a farmer’s son, who, by comparison to Abraham, is lean and spare. None cuts a particularly exciting figure on this bitter November day.

As they wait for William to finish his conversation, Seth stands with his hands linked behind his back and rocks on his heels, like an old man awaiting the appearance of a tardy grandchild or a fussing spouse, and occasionally tips his head back to peer up at the enormous gold sun-burner suspended above them. Each time he does this, Kate stares at the bulge of his Adam’s apple and wonders why she can summon no romantic feelings for this man, who is tall, and wears the broad shoulders of a boxer, and who, at twenty-one, is much closer to her own age than is William, at nearer thirty. She knows it to be an impossibility, so frequently has she tried to distract herself from William with thoughts of Seth, but still, she can’t help but wonder at it. No blushing. No churning. Nothing. The wiser option holds no appeal for Kate.

‘Can you feel the heat off that thing?’ he says now, though of course they all can. The sun-burner has been lit for some hours and, in contrast to the temperatures outdoors, it feels as intense as a blistering hearth fire.

The others lift their heads dutifully to the embellished gold crown the burner has been fashioned into. It looks to Kate as though it must have cost a year of her father’s wages. She cannot see the need for such a piece of ornamentation when the entertainment will surely be onstage, and ought to be sufficient to keep any audience member’s eyes from drifting upwards. She says as much, and is met with grins from the women and a serious glance from Abraham.

‘But the girl is right,’ he drawls. He has called Kate ‘the girl’ since their first meeting; it does not rankle her any less with repetition. ‘We’ll have to be more than spectacular just to compete with the walls in this joint.’

‘If you don’t imagine yourself any more interesting than the walls, Abe,’ Kate replies, ‘then I don’t suppose there’s much hope at all for your performance.’

At this, Abraham laughs a little too loudly and the others snigger. Secretly, they appreciate his fears. The Washington is by far the grandest venue they have yet performed at. The seating – they have lately overheard the theatre manager boast – can accommodate over nine hundred persons. The furnishings, from the wood-panelled ceiling all the way down to the boards, are complementary shades of cream and ivory. The balconies are decorated with papier-mâché mouldings, accentuated with gold to match not only the enormous sunburner but also the intricately cast Wenham lamps positioned under the galleries.

The impression is of fire and stars and the gods.

Though they are poking fun at Abraham, William’s troupe know they will have to shine here.

‘We’ve got two days,’ Mabel says. ‘And William says there’s a rehearsal space near the hotel. The bloody walls will have nothing on us come Saturday.’

‘Right enough, too,’ Anna nods, crossing her arms over her bust.

Onstage, William is shaking hands with the theatre manager, who does not stand straight enough to take possession of his gangling frame, but instead slumps over his own pot belly like a man defeated. William could teach him something about posture, Kate thinks; and strength; and grace. It seems to her that William knows everything there is to know. After all, it was he who had noticed her potential, encouraged her to visit the gymnasium, first held a weight bar over her head and lowered it into her open palms. He alone has taught her what she might be.

And that, she decides, is why she really will write to her parents as he has asked.

She will say, I am come to London to make my way in the music halls. I shan’t return home except to visit, if you will have me. I am safe with William Roberts’ troupe, and assure you that there is nothing shameful in this life.

Even as she designs the letter, her mind wanders to the page torn from the Pall Mall Gazette which Mabel had pinned up on the wall of the Tudor Street gymnasium a year or two before. It flutters there still, faded into blankness – or had, the day before they left. Mabel had taken a pencil and circled a sentence which claimed that ‘no girl ever kept her virtue more than three months’ in some London theatre or other – Kate recalls the phrase perfectly, if not the location. But what does that matter? Kate will not lump herself in with all those other girls. She is to be her own woman, whatever the cost to her soul.

My mind is made up, the letter will end. I am to be a strongwoman.

The troupe takes to the rehearsal room almost immediately, pausing only to change into their leotards, tights, and belts. They find it decked out with all the dumb-bells, barbells, kettlebells, and Indian clubs they could need. On one side, the room has three large, high windows, through which they can see only the roof slates of the building opposite and the jackdaws which congregate around its single chimney stack. On the other hangs a wide mirror, slightly misted, in which they watch each other’s distorted reflections. Within the hour, the room smells of sweat and talcum powder. By that evening, the air is heavy with their exhaled breaths. At nine o’clock, William disappears to fetch sandwiches and, on his return, they sit on the dusty floor, tired and sticky, and chew through thick cuts of bread filled with cheese or egg or salmon paste. Or, in Seth’s case, sliced apple and pickles. They curse him for that choice when they arrive back early the next morning and begin again – talcing up, lifting, spotting, adjusting.

And all the while Kate watches William, and William watches Kate, and something – something she does not know how to name – begins to shift.

By dusk on their second rehearsal day, they are, all six, wet-haired and spent. Their chatter has sunk into silence. They listen to each other’s joints creak as they brace and lift.

‘All right,’ William announces, setting down the barbell he had been overhead pressing. Kate watches a trickle of sweat meander down his temple and swallows the urge to lick it away. ‘That’s enough.’

There follows a murmur of dissent, but it is half-hearted, and Anna, Seth, Abraham, and Kate are lowering their weights to the floor even as they make it. Only Mabel holds firm, staring into the mirror and curling a dumb-bell with inhuman regularity: she has always been the most disciplined.

‘We’ve got all evening,’ she pants between curls. ‘Tomorrow morning, too.’

‘We’re ready, Mabel,’ William replies. ‘Overdo it and the performance will suffer.’

‘What do you intend instead?’

‘Drinks!’ Abe suggests.

‘An early night and a good breakfast,’ William counters, laughing and reaching out to slap at Abraham, who dodges him. ‘Besides, I can’t stand to look at your scowling mugs for a minute longer. Go back to the hotel, take a hot bath, sleep, and I’ll see you all tomorrow morning. Thank you for your hard work. Now get out of my sight.’

When the others start to wander out, Mabel finally relinquishes the dumb-bell, raises her arms into a cursory stretch, then moves after them.

‘Any help tidying up?’ she asks from the door.

William, who is collecting the Indian clubs up in one spread hand, keeps his eyes to the floor as he answers. ‘Kate offered,’ he says, and at the words, the implication of them, Kate’s head starts to pound. She has done no such thing. Colour floods her cheeks and she angles her face away from Mabel, so that the older woman does not see and question it. Ridiculously, tears are welling along Kate’s lower lids. Don’t be stupid, she tells herself. He could need you to stay behind for a hundred different reasons. And yet, the way he had looked at her…

‘We’ll manage between the two of us,’ he says.

‘If you’re sure,’ Mabel replies and, giving her customary wink, she swings around the door frame and is gone.

Kate does not know whether it is Mabel’s retreating footsteps or her own heartbeat she can hear as she watches William set five Indian clubs down on the middle shelf of the iron storage rack positioned in a far corner. The wooden clubs bump against each other, making a dulled thunking sound. William straightens up and moves across to the kettlebells. Lifting one in each fist, he positions them on the shelf below the clubs. He moves calmly and methodically, as though there is no one else in the room. He does not glance up to meet Kate’s scrutiny. In fact, he seems to avoid it. He is nervous, Kate realises. And she knows it is her heart she can hear then, for it is louder than a marching band, and, to her mortification, there is nothing she can do to silence it, because she knows suddenly that William is going to kiss her. He is going to clear up the mess – perhaps he needs the time, the distraction, to ready himself – and then he is going to stride across the room and claim her. She knows it. She does not move to help him to slide the bars into the rack or roll away the mats. She only stands, and waits.

She has been kissed before. After her first weightlifting appearance, at the Pontypool fete, she had sat around in the bandstand with a group of school friends – all of them laughing at nothing and clumsily touching each other’s legs or backs or shoulders to see what would happen. It seemed they had been hunkered there for hours before a quick black cloud scudded over, bringing with it a heavy downpour. The rain was cacophonous on the bandstand roof, and they had stood and shrieked about the noise, until a boy in the class above Kate’s grasped her hand, dragged her down the bandstand steps, and started her running across the field towards the shelter of the trees. Beneath their slick green canopy, they soon discovered an old sweet chestnut, hollowed out, and ducked inside, where they could stand straight up in the emptied chamber of the trunk. The kiss itself was forgettable. Kate had found herself uninspired and eager to have it over with. But the sweet chestnut she remembers vividly: the dark, wet weight of it surrounding her; the tapping of the rain against its long leaves; the damp stench of the litterfall beneath her boots against the salty tang of the catkins. She had felt herself somewhere other, unfamiliar. And that was far more exciting than the fumbling boy at her lips. The world and all its beautiful possibilities had stolen in and ruined that kiss.

But with William, she is certain, it will be quite the opposite. When William kisses her, the rest of the world will cease to exist.

To signal that he has finished his task, William brushes his hands across his thighs, leaving two smears of white talc in the cotton: the imprint of his fingers makes them look like wings, feathering into flight. Then he balls his fists, rests them against his hips, and finally turns to look at Kate.

Kate is a statue. She has not moved an inch since Mabel descended the stairs and left the exterior door to slam behind her. She wonders now if she can move, or if perhaps she really has hardened to stone. She cannot think of a word to furl over her tongue, or how to impel her limbs into movement, or whether she ought really to be standing alone in an empty room in an unknown city with a man of twenty-eight, however much she might want to. Perhaps she is not ready for what might follow. She knows something of it – rumours and imaginings and the occasional stifled sound through her parents’ bedroom wall – but not enough. She is not experienced. She is not quite a woman. She is not William’s wife.

And yet, the longer he looks at her, the bolder she feels herself becoming. In her leotard and tights, every line of her body is visible to him, but she experiences no urge to cover herself up. Instead, she pushes back her shoulders and stands straight – not a statue after all – and wonders, unexpectedly, if the dark points of her nipples are evident through the black pull of the cotton. She hopes vaguely that they are. The idea that William might put his eyes on any bared part of her sets her stomach fluttering. What she wants – so physically that she trembles against the urge – is to tear the fabric open and reveal herself to him. It doesn’t matter that she is unsure of what comes after. She wants to open herself to William. Only William. A scenario enters her mind, whereby ripping the leotard isn’t nearly enough, and she begins to peel away her skin, and then her muscle, until he can peer into her chest cavity and watch her heart throbbing and tremoring.

‘William,’ she manages to say, finally. The word is sugar and vinegar on her tongue.

‘I’m glad you stayed,’ he replies. His bunched fists remain at his hips. His stance is wide, business-like. The small leather ballet slippers they all wear to train are an absurdity over his thick, knotted feet.

‘Yes…’

Still, neither of them has moved. From the chimney top at her back, a jackdaw croaks out a sermon of its own – about sin, probably.

‘There’s something I wanted to show you,’ William continues. ‘It’s a surprise, of sorts, but I hope you won’t mind it.’

‘Should I?’ Kate asks. ‘Mind it?’

William shakes his head, smiles just a little. ‘I should hope you’ll be impressed. Come.’

He indicates the door of the rehearsal room, and Kate moves towards it blindly. In the hallway, she waits for him to lock the door, then makes to descend the stairs. Back to the hotel, she thinks. Where else would they be going? But William stops her with a raised arm.

‘This way,’ he says, tipping his head towards another door. This one has no glass panel and she can discern no chink of light around the frame. William grabs the handle and turns it; it is not locked. Within is only darkness and the acrid smell of stale air. Kate looks confusion at William, who smiles wider.

‘You don’t expect me to get inside?’ she asks. The disappointment she would feel at another fumble in the darkness. With William, she has already decided, it will be all light and clarity.

William laughs and shakes his head.

‘Wait,’ he says. He moves into the darkness and begins shuffling about. A moment or two later, he emerges, carrying a large board – perhaps four feet in height. He holds it side on, so that only its three-inch width is visible.

‘Close your eyes,’ he instructs.

Kate hesitates. Already, her anticipation is sinking into disenchantment. This cannot be the beginning of what she had intended. This is … what, then? A game? She narrows her bright round eyes into dashes of doubt. Her temper is brewing. When stirred to, Kate gathers and breaks like a storm.

William twists his mouth, challenging her as a father might a tantruming child. That he is a father is a fact Kate can barely take hold of. In some dark fold of her mind, she knows that William and his wife share three peachy babies: the eldest just five; the youngest but a year old. But she knows it in the same way as she knows that there are parts of the Earth forever deep in snow, or that, whatever her father preaches, there is no being called God. William’s family is a distant thing – a story almost – and it is not her concern. If it were, William would speak to her of them. The fact that he does not persuades her that William is building two separate lives for himself. One with Alice; another with his troupe. The second, she might be a part of.

‘Close your eyes,’ William says again.

This time, Kate acquiesces. She listens as he scrapes the board out into the hallway. Behind her lids is William’s squared silhouette.

‘All right. Open them now.’

She does, and finds that William has made a sandwich-board boy of himself. His disembodied head grins madly.

‘Read it, then,’ he says.

Kate scans the board. In tall, sharp letters is written, Atlas and Vulcana: the World-Famous Brother and Sister Strongperson Act.

‘Who are Atlas and Vulcana?’ she asks, frowning.

‘We are!’

Her frown deepens.

‘Or we will be. We’re going to reinvent ourselves, play the characters. Star act only, you said. I thought we could share it. You and I, Kate. Atlas and Vulcana.’

‘Brother and sister…’ she reads slowly, swallowing an odd clag of deflation.

William shrugs. ‘It’s a good hook.’

‘But…’ She shakes her head, trying to find the direction of the conversation. ‘You can’t have had this made up in two days.’

‘No,’ he admits. ‘I made an order in advance.’

‘And what if I hadn’t come?’