Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

William Blake is a private detective. When he is asked by an eccentric scientist to investigate the where-abouts of his amnesiac missing wife, Louise, Will finds himself entangled in layers of deceptions and disappearances that lead him inexorably back to an unsolved mystery in his own past: the loss of his young daughter Emily. The case takes Will to brothels, nightclubs and amusement arcades in the Scottish seaside resort of Portobello. Identities become con-fused as his sexual obsession with a nightclub singer becomes entwined with sightings of Louise, his own torturous memories, and new visions of the lost Emily. The Existential Detective is a surreal, dreamlike story of loss, incest and what it means to remember.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 210

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Existential Detective

William Blake is a private detective. When he is asked by an eccentric scientist to investigate the where-abouts of his amnesiac missing wife, Louise, Will finds himself entangled in layers of deceptions and disappearances that lead him inexorably back to an unsolved mystery in his own past: the loss of his young daughter Emily.

The case takes Will to brothels, nightclubs and amusement arcades in the Scottish seaside resort of Portobello. Identities become con-fused as his sexual obsession with a nightclub singer becomes entwined with sightings of Louise, his own torturous memories, and new visions of the lost Emily.

The Existential Detective is a surreal, dreamlike story of loss, incest and what it means to remember.

Praise for Alice Thompson

“If you can have degrees of uncanniness, The Existential Detective is Thompson’s uncanniest – and best – novel yet. Private detective William Blake is hired by an eccentric scientist to find his missing wife, Louise, who may have lost her memory. Just as Freud’s theory of the Uncanny insists that a man wandering around lost will repeatedly fetch up in the red-light district, Will’s search takes him to a brothel and to a nightclub, where he develops a sexual obsession with a singer.” —NICHOLAS ROYLE, The Independent

“The Existential Detective is a deeply moving and compelling read, packed with mysterious goings-on and bloodcurdling shocks, all counterbalanced by the author’s trademark subtle and elegant prose. The story is intricately woven and Thompson wastes no time in conjuring up an eerie atmosphere that makes even a simple act seem loaded with meaning. Of course, it’s a departure of sorts for Thompson too, and she subverts the crime fiction genre with aplomb, breaking new ground while still retaining her distinctive voice. Remarkable.” —CAMILLA PIA, The List

By the same author

NOVELS

Justine(1996)

Pandora’s Box(1998)

Pharos: A Ghost Story(2002)

The Falconer(2008)

The Existential Detective(2010)

Burnt Island(2013)

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Alice Thompson, 2014

The right of Alice Thompson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

First published by Two Ravens Press 2010

Second edition published by Salt 2014

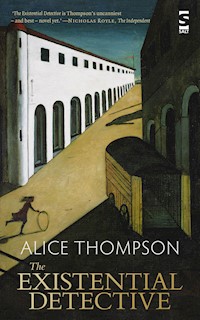

Cover art:The Mystery and Melancholy of a Street, 1914 (oil on canvas) by Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978).

Private collection | The Bridgeman Art Library.

© DACS 2009

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-012-6 electronic

To Chris and Jen

Mister Sandman, bring me a dream

Make him the cutest that I’ve ever seen

Give him two lips like roses and clover

Then tell him that his lonesome nights are over

Sandman, I’m so alone

Don’t have nobody to call my own

Please turn on your magic beam

Mister Sandman, bring me a dream

Mister Sandman

PAT BALLARD

Theimage of the cruelsandman now assumed hideous detail within me, and when Iheard the sound of clumping coming up the stairs in the evening I trembled with fear and terror. My mother could get nothing outof me but the cry ‘The sandman! the sandman!’ stammeredout in tears. I was the first to run intothe bedroom on the nights he was coming, and hisfearsome apparition tormented me till dawn. I was already oldenough to realize that the tale the old woman hadtold me of the children’s nest in the moon couldnot be true; nevertheless, the sandman himself remained a dreadfulspectre; and I was seized with especial horror whenever Iheard him not merely come up the stairs but wrenchopen the door of my father’s study and go intoit. There were times when he stayed away for many nights;then he would come all the more frequently, night after night.

The Sandman

E.T.A. Hoffmann

1

PORTOBELLO WAS A place where you could find anonymity, and Will enjoyed the faded seaside resort’s genteel seediness because it demanded nothing from him. The pale deserted promenade that ran along the edge of the flat sea, the mishmash of small Georgian cottages and red stone tenements and the amusement arcade seemed to represent to Will his own pleasurable disillusionment. Of medium height, he appeared inconspicuous – he liked to blend into whatever landscape he was walking into and his ashen skin made him look as if he slept under rocks. Dark curly hair overshadowed a strong face which was slightly concave but detachedly handsome, as if the world had given him a few punches over the years and then stepped back to admire its handiwork.

It was a typical autumn day as Will walked along the promenade. The seagulls were as clamorous as ever. The rain of the night before had been heavy and he could hear the water rushing down the huge pipe that ran beneath the promenade and led directly into the sea. There was no wind. The sea was still. He loved the windless days.

Shrugging off his raincoat, Will climbed the stairs to the small office, above the fish-and-chip café, where he worked and lived. The sign on the door read William Blake, PrivateInvestigator. Over time it made him smile, for he investigated the most secret and sordid matters, generally involving infidelity or fraud, until the word private had become blurred with his knowledge of other peoples’ lives.

He quickly glanced around the room to check nothing had been disturbed. A few days earlier he had been broken into. A few papers had been rearranged and some old family photos he hadn’t looked at in years had been scattered across the floor, but nothing had been taken as far as he could see. In fact, something had been added: he had found the packaging of a disposable camera in his wastepaper bin.

Today was a boring day. A few phone calls about forged cheques, filial deception and a missing cat. That evening, he retired to his living room which lay at the back of the flat and looked not over the sea but over another row of tenement blocks behind. He always entered it with a sense of relief; it was a sanctuary from the chaos.

He bent down to pick up a parcel just behind the door that had been hand-delivered that morning; only his name was typed on the front. He shook it. Bits inside rattled. He tore off the brown paper – inside there was a box with no accompanying note or letter.

He opened it up to find a jigsaw. It must have been sent by someone who knew he liked puzzles. The pieces inside were tiny; it looked fiendishly difficult, he noted with delight. They were mostly greys and flesh tones with the odd flash of colour. Will stared at it until he grew so tired he leant his head on the table and fell asleep. He woke up after midnight, his head aching, and collapsed into bed without bothering to undress.

The next morning it was raining again, but even harder. It rained so hard as he worked at his desk that it seemed as if his thoughts had turned to a relentless patter of water on stone. Outside his window, the sky and sea merged in a seamless grey. The seagulls were fighting for sodden bread left on the sand by the little Chinese girl, Lily. She generally fed them old fish from the café below every morning. He could hear the gulls squabbling. It annoyed him, the way she kept feeding them. The birds’ noise was such a distraction, but he couldn’t be bothered to ask her to stop.

There was a knock on the open door of his office. Will looked up. Standing in the doorway was a tall man wearing a shabby brown corduroy suit. He slumped down in the chair opposite Will’s desk, gazing at him with benign, appraising eyes.

It was faces that Will liked to read most. Faces that told their stories. He could read lives in their lines, the shape of their jaw. Youth was a good disguise: its puppy fat and smooth skin were like blank pages. But age, yes; age marked people.

Will, on the other hand, like to keep his own face impassive. He knew one of the rules of detecting, one of the cardinal rules, was not to be read first. Preferably not to be read at all. For the detective was not part of the story but the outsider looking in: the reader, not the book. Will was there to solve cases – if his presence affected events, clues would be disturbed, ripples made in the water.

The client took from his pocket a small photograph and laid it on his desk. Will looked down at the photo. It was a picture of a young woman, about twenty years old. She had an extremely smooth, moulded face, like a mask, with a straightly chiselled nose and almond-shaped dark eyes.

‘I’d like you to find my wife.’

Of course she was his wife, Will thought. This client would have been the sort of man attracted to an immutable girl like that. He had an almost feminine face and large green eyes that made Will think he must operate in instinctive, clever ways. His presence was dynamic: not dominating or overbearing but closed-off and intense, as if all his thoughts had trapped his emotions within him and they were now clamouring inside like small wild birds. Why had he at first thought the client was her father? He judged his client to be about forty years old, old enough to be her father.

‘You’ve lost her?’

‘Four days ago. I came back home from work and she’d gone.’

‘She’s normally at home waiting for you?’

He shrugged his shoulders noncommittally. ‘And you haven’t seen her since?’

‘No.’

‘And you are?’

‘Adam Verver. Dr Adam Verver.’

‘When was this photo taken?’

‘About a year ago.’ He had a quiet voice. ‘She still looks the same.’

Verver paused, about to say something, and Will waited for him to continue. He was good at hearing the rhythm and patterns of conversation, the tiny heartbeats of silence.

‘She suffers from amnesia,’ Adam finally said.

He seemed reluctant to elucidate. Will knew better than to go further than a client wanted on a first meeting. His job was not only to solve a case, it was to let the client see that he could be trusted. That way, he could generally get more information in the end. This man was the touchstone to the solution. The one closest to the disappeared generally was.

‘I see. But she knows who she is?’

‘She can remember everything of the past four years. But no memories before then.’

Will tried a different tack.

‘What about a friend she may have visited?’

‘She didn’t have friends.’ Dr Verver managed to make “friends” sound like the name of an infectious disease.

‘Who was the last to see her?’

‘My parents, Lord and Lady Verver. And their staff.’ Dr Verver spoke of his parents very neutrally. Will couldn’t detect any antagonism.

‘And you haven’t contacted the police?’

‘I’d rather not. It’s a personal matter.’

‘I understand. I’ll need to question everyone in the house.’ Dr Verver gave him the address of his parents.

‘I’ll come round this afternoon.’

‘I’ll let my father know.’

‘I will also search your wife’s room. And look around your house.’

‘Of course. It’s not a house, actually. It’s a flat.’

‘Do you and your wife live there alone?’

He was careful to use the present tense; not to put her in the past tense. Adam nodded.

‘And your work is?’

‘I’m a scientist.’

‘Ah.’ It explained a kind of subtle arrogance about him. Will couldn’t resist looking at his client’s hands, long fine fingers. This man in front of him, he thought, was only interested in what Will could do for him. But for money, so Will didn’t mind that.

‘I work long hours. It’s my life.’

Will nodded. He knew what he meant.

Will belonged to the Association of Private Investigators. A lot of his cases involved marital betrayal, which involved working night and day. He spent a lot of time examining theatre tickets and drink receipts. Infidelity meant business to him. It was usually married women who came to him. If only women knew, he thought, what infidelity meant to some men. How little it meant.

He had learnt never to get involved in a case, to always remain one step removed. On the whole he was helping the victims. It was the betrayers, those who deceived, that he traced. He was once told by a jealous wife that she would like to take out a contract on her husband’s mistress. He said no. Will believed in unconventional justice but he drew the line at contract killing.

Technology hadn’t made much of a difference to detecting. Nothing in the end could replace the efficacy of following someone. Following the traces, standing in doorways, looking at what was behind you in the reflection of shop windows. Following someone who did not know they were being followed, didn’t even know of his existence.

2

LILY WAS FEEDING seagulls again on the beach. The seagulls fluttered violently around her, above her head. Her oriental face was still and placid, as if her emotions had flown into the birds around her.

‘Hi, Lily,’ he said.

She turned round and looked at him. She never smiled. Always gave him the same serious look of recognition when she saw his face.

‘You don’t think you may be overfeeding them? They’re beginning to look a bit fat.’

‘You just don’t like me feeding them.’

‘What’s wrong with them catching fish?’

‘It’s hard for them to get the flies on the hooks.’

‘Lily, facetiousness isn’t attractive.’

‘Well, then you should try something else.’ She then turned to feeding the gulls again.

They were a close family in the fish-and-chip shop. Extended family with that detached sense of happiness only real intimacy can bring and Will looked upon it with fear. The Chinese family chattered amongst themselves but mostly he would see them working hard in the café. He often saw Lily cleaning the tables and sweeping the floor after school, the smell of the frying fish accompanying her out into the sea air.

At the east end of the Promenade was a row of Gothic houses. With their turrets and towers they reminded Will of a stage set out of A Hammer House of Horror. Designed in the mid-nineteenth century, they had been built originally for rich merchants who wanted to show off their wealth. The gardens were larger and set further back from the promenade than the other houses and clearly still had moneyed owners.

The garden of Lord and Lady Verver was fronted by a large wall and an iron gate, shutting it off from the rest of the world. Stuck on a lamppost outside their house was a ‘missing person’ poster for Louise Verver – in mint condition, it reminded Will of a poster for a missing cat. Above her picture were the words:

MISSING

Louise Verver

5’4”. Darkbrown eyes, brunette, medium build

Suffers from amnesia

He looked at her face again. The expression in her eyes had a quality he couldn’t fathom. It wasn’t sadness, he thought, nor was it fear. He flickered over her long brown hair, her cheekbones, her narrow nose. He realized, as he took a step back, looking at the whole face, what it was. It was a lack of any emotion at all; it was an absence of character.

He went up the path and rang the doorbell. He waited a while before the housekeeper opened the door. She was an unfriendly looking woman with short greying hair and an unmade-up face. She tried to smile.

‘Good afternoon. I’m William Blake.’ He showed her his card. ‘I’ve come to ask Lord Verver about the disappearance of his daughter-in-law.’

The housekeeper’s fixed smile at once vanished.

‘Ah yes, of course. It’s all worrying. Very worrying. Come in. I’m Mrs Elliot. They call me Mary.’

She ushered him into the grand entrance hall. His footsteps echoed on the black and white tiles. For a moment, the housekeeper scuttled about rearranging letters on a side-table. He noticed her distracted manner. As duplicity was part of his work, it made it easy for him to recognize it in others.

A moose’s head hung above a heavy stone fireplace that was carved with gargoyles, and a large staircase wound its way up to the first floor. There was money in the Ververs’ house. The painting, the Persian carpets, the thin coldness of the air, all whispered wealth.

The atmosphere was not ostentatious, just pervasive. But strangely, there was also a faded careworn feel to the house: the carpets were threadbare. A powerful smell of lilies from the hall table mingled with a smell of must, reminding him of a funeral parlour.

‘Your staircase bannisters are looking very shiny, Mary,’ Will said.

As she turned to admire them herself, Will quickly glanced down at the side-table where she had slipped a letter under a pile of documents as he had come into the hall. He pulled it our from under the pile.

It was a half-opened brown envelope addressed in clumsy misspelling to Adam Verver. The edges of some photographs were peeping out. He wondered if Mary had taken a surreptitious look at them and was now protecting the son of her employer.

‘What did you think of Louise?’ he asked as she turned around again.

‘Oh, a very nice lady,’ but her lower lip went down slightly, in a kind of grimace.

On the first floor she crossed the landing to a large oak door and opened it. Will entered a large living room and Mary quietly shut the door behind him. The view of the sea was breathtaking, stretching out to an empty horizon. Because of the perspective, the promenade and beach were out of view – it was as if the house was protruding out of the sea.

‘Hello, Mr Blake. You’re the detective who’s come about Adam’s disappearing wife, I suppose. My son told me to expect a visit from you.’

The large booming voice startled Will: a resonant, centuries-old voice, as if pulled tightly over Stradivarius wood. In one of the dark corners of the room sat an old man in a wheelchair, his legs covered by a tweed blanket.

As he wheeled himself slowly and deliberately out of the shadows into the light, his shrunken persona contrasted with his deep dominant voice. His voice was far larger than the real man, reminding Will of the wizard of Oz. The rug slipped off to reveal two withered and lifeless legs and William bent down and placed the rug back over him.

‘That’s very kind of you, young man. If you ask me, she’s just wandered off. Forgotten where she is. Someone will find her and bring her back in, I’m sure.’

He sounded as if he were talking about a stray dog, William thought: one without a pedigree.

‘Has she done this before? Wandered off like this?’

‘Women nowadays are a dissatisfied lot. Always bemoaning their fate. My wife is just the same. As if we all didn’t have a fate to bemoan.’

He looked down at his legs.

His face still was handsome, in spite of the drawn skin – ancient and wrinkled like parchment written over many times in ink. He looked chivalrous. He had a strong jawline and high forehead that made him seem incisive, analytical, not prone to emotion or self-knowledge. Hardly sexual now, but once would have been, very. But there was also something about his face that was self-centred, a sense that things were his due.

‘So she has gone missing before?’

Lord Verver hesitated. He took out a cigarette from a silver lighter case and lit it. He inhaled, all the while keeping his gaze on Will. He had a piercing glare. He was under no illusions, Will thought. He knew all about human nature, what men and women were like.

‘How can I put this tactfully, Mr Blake?’

‘In my line of work, Lord Verver, tact just tends to delay things.’

‘Indeed. Indeed. A few months ago she started going down to the amusement arcade. Hours she would spend there. To play on those damned machines.’ He smiled dryly. ‘She seems to have an affinity with them.’

‘She likes to gamble?’

Lord Verver snorted. ‘It seems so.’

So what kind of person did Louise Verver’s gambling make her? Someone who wanted to escape from reality. Someone who liked to think they could control the outcome of their gambling. Gamblers didn’t believe in luck. They believed in the power of mind over matter.

‘Did Adam argue with her? Try to stop her?’

Adam’s father wheeled his wheelchair into the adjacent conservatory, picked up a watering can, and began to water the tomatoes.

‘Of course. Isn’t that what the spouses of gamblers do? It becomes a way of life to try and stop them.’

‘But it never got violent?’

‘Of course not. I never saw him raise a finger to her. Or heard anything to that effect.’

‘You never saw her with a black eye? Anything of that kind?’

‘No.’ He held Will’s gaze.

The Ververs were very wealthy, he thought. They had a sense of privilege that was ingrained in their character. He wondered what Adam thought of his wife haunting the amusement arcade.

As if reading his mind, Lord Verver said quickly, ‘Adam indulges her. Will do anything for her. Besotted by her. The kind of infatuation that certain intense men hold for their wives, that excludes everything else.’

Why was Will getting the impression that Lord Verver was lying?

‘When would she gamble?’

‘Any time, day or night. Very odd girl.’ There was latent anger in his voice now. It was the first time he had showed emotion. In Will’s line of work anger was often the first emotion you saw in people. Anger seemed to be the default emotion. People fell into it, as if the other emotions were too much hard work, but anger was a walk in the park.

‘She had amnesia when Adam met her?’

‘Yes. He brought her into our lives like a magician pulling a rabbit out of a hat. She was a young rabbit at that – just sixteen. He seemed to conjure her up out of the air. No memories at all as far as I could tell. But she was eager to please, in full possession of her faculties and all that. Ironically, recently she seemed to be getting some memories back.’

Will wondered if “ironically” was the right word. Perhaps there was a connection between her memory coming back and her disappearance.

‘Her childhood memories?’ he asked.

‘Yes. Just in the weeks that led up to her going missing. She was becoming very confused.’

‘Well, thank you, Lord Verver. You’ve been very helpful.’

‘Glad to have been of help. Puzzling case. Most puzzling. You must understand, my Adam is a very unusual person. Just because he’s eccentric doesn’t mean he’s violent. He may be erratic and so on. That’s why people tend to misunderstand him. They get the wrong end of the stick. You know the kind of thing, I’m sure.’

‘I do. For some people the wrong end of the stick can be like a magnet.’

Lord Verver gave a chuckle. ‘I’m glad you understand.’

He wheeled himself vigorously forward and shook Will’s hands. As Will was leaving the conservatory, he turned round to see Lord Verver picking some dead leaves off the tomatoes. He looked pale and anxious. The stern autocratic face had become vulnerable and frightened. And Will guessed it probably didn’t have anything to do with the mildew on the Little Napoleon fruit.

William left the house. The father and son were an odd pair. One bluffly masculine, in spite of paralysis, the other introverted but passionate. And this strange missing woman at the centre of the case, connecting the father reluctantly with his son. Will wondered if the real tension was not between Louise and her father-in-law, but between father and son. Louise fulfilled a useful function, as scapegoats often did in a family. They made everyone else in the family feel normal. He still felt that he didn’t really have an idea what she was like. Her behaviour, yes, but not how she was.