Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Award-winning writer Alice Thompson's compelling new novel is a story of transformation; an exploration of the shifting borderlands between imagination and reality. It is 1936. Iris Tennant has applied, under a pseudonym, to become personal assistant to Lord Melfort, the Under-Secretary of War, at his estate in the Scottish Highlands. Her plan is to find out why her younger sister Daphne committed suicide there a year previously. As Iris gradually falls under the spell of Glen Almain, she starts to see the apparition of Daphne haunting its glades and begins to wonder about the manner of her death. Is there really a beast that inhabits the woods? Who is the mysterious falconer? What actually happened to Daphne, and is Iris destined for the same fate? A backdrop of impending war and the spectre of Nazi Germany loom over this strange, dark tale. What ensues is a battle between instinct and reason, fantasy and history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 201

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Falconer

Award-winning writer Alice Thompson’s compelling new novel is a story of transformation; an exploration of the shifting borderlands between imagination and reality.

It is 1936. Iris Tennant has applied, under a pseudonym, to become personal assistant to Lord Melfort, the Under-Secretary of War, at his estate in the Scottish Highlands. Her plan is to find out why her younger sister Daphne committed suicide there a year previously. As Iris gradually falls under the spell of Glen Almain, she starts to see the apparition of Daphne haunting its glades and begins to wonder about the manner of her death. Is there really a beast that inhabits the woods? Who is the mysterious falconer? What actually happened to Daphne, and is Iris destined for the same fate?

A backdrop of impending war and the spectre of Nazi Germany loom over this strange, dark tale. What ensues is a battle between instinct and reason, fantasy and history.

Praise for Alice Thompson

“Thompson’s writing is, as ever, the kind that demands full attention – important details are embedded in lyrical description or insinuated into an apparently innocuous observation. This is not a book that is kind to readers – you have to buy into the world its author has created, accept its own very special laws – and that requires effort. But it’s effort that is ultimately rewarded: I doubt you’ll read another book quite like it this year.” — The Scotsman

“The world she creates is claustrophobic and hypnotic, recognisably a dream but also rational on its own, admittedly skewed, terms . . . Many novelists bore readers to sleep. Wake up to The Falconer.” —The Sunday Herald

By the same author

NOVELS

Justine(1996)

Pandora’s Box(1998)

Pharos: A Ghost Story(2002)

The Falconer(2008)

The Existential Detective(2010)

Burnt Island(2013)

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Alice Thompson, 2014

The right of Alice Thompson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

First published by Two Ravens Press 2008

Second edition published by Salt 2014

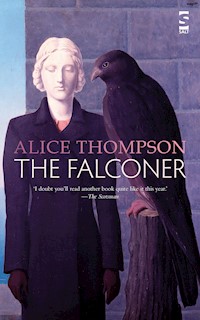

Cover Illustration:Les Eaux Profondes1941 by René Magritte, Private Collection, courtesy of Fondation Magritte and The Menil Collection © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2008

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-010-2 electronic

To A.D.T. and M.A.

Thank you

Full fathom five thy father lies.

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes;

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:

Ding-dong.

Hark, now I hear them.

Ding-dong, bell.

The Tempest

1

THE LONG TRAIN journey began to take on the form of a monotonous dream. However, the landscape continued to mutate outside beyond the window. Cities turned to grass and then fields rose up in the shape of mountains. Light was fading in the carriage where the solitary passenger was sitting but she didn’t notice the shadows falling over her. Iris Tennant was going where she would find space and solitude. She would be leaving behind the city full of strangers.

One by one, the gas lamps of the remote cottages outside were being lit. These cottages looked self-contained, so enticing out there in the dusk. She wanted the train to stop for her so that she could get off and walk across the fields to one of them. To disappear into one of those little glowing homes with low slung roofs and rough patches of field sloping down to the river.

From outside her door, the train guard switched on the compartment light. Iris turned from the window and pulled out a novel from her handbag. She had just completed the first page when there was a sudden screeching of brakes. The train was approaching the next station. It came to a stop, billows of steam obscuring her view of the platform. A few moments later the whistle blew and the train started up again, juddering so much that the words of her book began to dance about on the page. As she tried to focus on the print, she became aware that a man had entered her carriage.

The passenger stopped just inside the carriage door and removed his trilby to reveal a finely drawn face with guarded eyes. He seemed slightly abstract, as if his face was an idealized version of a more primitive self. The tailoring of his pale suit had an understated finish. He lifted up a suitcase onto the overhanging shelf – the tan leather lid was smattered with peeling labels – and sat down on the wooden seat diagonally across from her. Iris wondered what this well-dressed man was doing in the third-class compartment.

She returned to her novel, but she became conscious that the stranger was staring at her. She looked up and met his eyes: they looked at her levelly. The irises were a very pale grey, like mist.

‘Forgive me,’ he said softly, ‘I saw you as I walked past your compartment. I had to come in.’

He spoke perfectly enunciated English – too perfect, she thought; she could hear the faint trace of a German accent.

‘Haven’t we met before?’ he asked.

‘I’m afraid you must be mistaken,’ she replied, keeping her voice flat. A tie-pin in the shape of an eagle glinted between the lapels of his suit.

Outside, the landscape was growing ever more desolate. The darkness of the wide-open countryside stretched out into the dusk for miles. The train rumbled on as if under its own momentum and she felt as if they were now flying, like witches, through the night air. The light of the train was throwing a peculiar glow on the man, making him appear more exact.

‘Now I look at you more closely, it’s obvious you are not her,’ he said. ‘The likeness has gone. I’m sorry; it must have been the odd light.’

A few moments later he stood up, took his suitcase down from the shelf and left the carriage. She crossed her bare legs. She could feel the line of sweat being drawn between her thighs, damp and hot. She looked down at her unpainted toes peeping out from between the soft, red-kid leather of her sandals. The faint trace of her lavender perfume was merging with the oily smell of the train.

The train gently swayed from side to side, as if trying to rock her to sleep. Suddenly it went pitch-black outside – the train had gone into a tunnel and the loudness of the roaring train was deafening. The light in the carriage now seemed insanely bright, the brash luminosity of an asylum.

Her reflection in the window was thrown into heightened relief. Iris saw her dark eyes looking back with their usual air of objectivity, her lips fixed in an unforgiving line. There was no aura of emotion in her long, indifferent face. Her face was in stasis; it was like looking at a portrait of someone who had died years ago. But then, just for a moment, the eyes became paler, more expressive, the nose narrower and shorter, the mouth more sensual; her sister’s face looked back at her, the backdrop of the reflected train carriage behind her.

And Iris felt for a certain moment that a parallel train was running beside her in the tunnel with Daphne sitting inside it. Daphne was giving Iris her direct, vivacious look with just the flicker of a smile at her lips, as definite and tinily specific as the quiver of a bird’s wing.

Alighting at her destination, Iris was surprised to see the man in the trilby get off the train, a few carriages down. A Bentley was waiting for him, which drove off into the darkness.

Iris stayed that night in the nearest village inn, and at noon the following day a hired car with a shaky undercarriage dropped her off at the bottom of Glen Almain. It was a hot day in early August, with the kind of heat that seemed to make the pale blue petals of the harebells tremble. The only signs of life were the flies hovering in the still air.

Carrying her suitcase, she began to walk up the glen’s road. She passed an old school-house, and noticed a small boy staring at her through the window. He was unnaturally pale, with hair as white as the seeds of a dandelion clock. Two dead falcons were pinned to the front door.

Almain Lodge house stood at the far end of the glen where the road turned into an avenue of trees. The lodge-house was situated almost at the foot of the mountains, and its roof and two large chimneys were visible just above the branches of surrounding fir trees. It had a small, well-kept garden of lawn and rhododendrons.

A woman stood at the door like the little wooden figure of a weather-house – out, because of the sun. She swept back her dark hair from her small, rosy-cheeked face with a calloused hand.

‘Miss Drummond, is it?’

Iris nodded.

‘I’m the housekeeper, Mrs. Elliot. I’m to take you up to the castle.’

The two women walked up the straight avenue, lined by huge beech trees whose heavy silver limbs reached out over their heads. A small loch lay to one side where the field dipped down, a rough causeway of stones leading to an isle at the centre of the loch. They walked for ten minutes along the avenue before reaching a huge cliff of red rock. The avenue turned sharply right into a cobblestoned courtyard. Veering up in front of them was a huge nineteenth-century castle made of red stone. Ornately turreted, the castle’s small paned windows looked feeble in the thick walls of red sandstone. They gave the baronial castle a secret, introverted look.

Down below the courtyard, towards the mountains, stretched the most beautiful formal gardens Iris had ever seen. Borders which ran along each terrace were filled with blocks of azure blue. Dahlias and hollyhocks of pink and white added a careful incoherence. Pale lemon roses, royal purple lavender and low box-hedges, laid out in different shapes, formed interweaving patterns. Ancient yew trees crouched along the edge of the lawns. Stone statues of men and women, mottled by age, stood elegantly positioned about the gardens as if in a petrified dance.

Suddenly there was a piercing shriek. Iris heard the rustle of wings and a tall, shining peacock strutted by her feet across the courtyard, dragging its train of feathers. It fanned out its tail in a brilliant display of emerald finery.

‘Miss Drummond? We’re waiting for you!’ called Mrs Elliot, who was lingering impatiently for her at the main door to the castle. Iris ran up to join her and followed her into the cold entrance hall. The darkness after the bright light of the gardens momentarily blinded her. As Iris adjusted to the gloom she could make out shields of faded heraldry hanging on the walls. The bare flagstones gave off a sweet and dusty smell. For a moment, Iris wondered what on earth she was doing here.

‘Lord Melfort had to leave suddenly on urgent business last night, for the Western Isles. It will be Lady Melfort who will see you tomorrow morning,’ Mrs Elliot said, and disappeared down the shadowy corridor as a girl not much older than fourteen, but with an overworked, whippet’s face, took Iris’ suitcase.

The housemaid led Iris up the servants’ stairs to an unassuming room on the first floor. An oak bed covered in a thick patchwork quilt lay next to a simple table and armchair. A chest of drawers stood in the corner and a threadbare rug covered the floor. That evening, as Iris prepared for bed, she wondered in which of the castle’s rooms Daphne had slept and what had been her dreams.

2

THE TABLE HAD been set when Iris came down to breakfast the next morning. A bowl of blowsy red roses filled a vase on the sideboard, and the breakfast was set out in silver platters below. She opened the lids to reveal creamy scrambled eggs, kippers shiny with butter and slices of hot toast. She was the first one down to breakfast and for a while she ate cautiously, in silence. She heard male voices outside in the hall and the sound of laughter and her heart beat slightly faster, but no-one else came in, and she heard the castle door shut behind them as they went outside.

A few minutes later a girl of about fifteen, wearing trousers and an open-necked white shirt, skipped into the room, helped herself to some toast and then turned round to see Iris for the first time. In the morning light she reminded Iris – with her wide open eyes, small mouth and triangular face – of a sylph. Pretty, in a sense – her skin as white as parchment, her eyes a dark black-blue – her elfin body looked as if it could contort in any way. Her choice of ill-fitting clothes accentuated her awkward movements. She looked as if, at the slightest confrontation, she would run away out of wilfulness.

‘I’m Muriel. You must be Daddy’s new private secretary. They don’t last long here,’ the girl said peremptorily.

‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ Iris replied.

‘But you mustn’t be afraid to ask for anything you want,’ Muriel continued in her bird-like voice. ‘There will always be someone to help you.’ But she said this in such a carefree way that Iris felt she meant the opposite.

Iris was due to meet Lady Melfort after breakfast. She knocked on the door of the drawing room at ten o’clock promptly. As she entered, Lady Melfort was already waiting for her, sitting on a sofa in the centre of a daffodil-coloured room, wearing a shot-silk dress of aquamarine that reminded Iris of the lustrous feathers of the peacock. Although about sixty years old, there was an energy to Lady Melfort’s angular features that caught the beauty of her youth. She gaily motioned Iris to sit down beside her. As she did so, Iris noticed her own plain dress was slightly frayed at the hem.

‘We don’t stand on ceremony here, Iris. Would you mind pouring?’ Iris leant over the small table bearing the teapot, picked it up and poured pale tea into two cups, delicately sprigged in forget-me-nots.

‘Your secretarial qualifications and references are very impressive, Miss Drummond. When we received them by post, we made the decision to hire you on the spot. And now that I see you in the flesh’ – Lady Melfort looked Iris up and down, proprietarily – ‘I see that we were absolutely right.’

Iris had grown used to the condescension of her employers. Her ability to detach, she thought, was her one source of strength.

‘You look much younger than thirty-five years old,’ Lady Melfort continued. ‘That’s what it said on your curriculum vitae, wasn’t it? Thirty-five years old. And unmarried.’

‘Yes, your Ladyship. ’

At her age, Iris thought, she was supposed to have been married by now; she was supposed to have had children. Sometimes she felt like King Midas. Everything she touched turned to gold. Her inability to love transformed everything it touched into metal. But it meant, she thought, that she remained undistracted from what she needed to do. And that she was often surrounded by beautiful, brazen things.

‘We thought, because of your age, that you would have sufficient maturity to do the job well. The last one was a bit younger. Emotionally unstable. Apparently it ran in her family. And it is difficult to find good people to come out this far into the wilds. Do have a biscuit.’

Daphne’s capriciousness, Iris thought, had been part of her allure. Her younger sister had fallen in love easily, passionately, and fallen out of love again with the same lightness. Love had seemed to Daphne arbitrary; something that swept over her and was gone, or drunk like the nectar of the gods, a temporary madness.

Iris took a piece of crumbly shortbread from the proffered plate.

‘Of course, you will find Glen Almain a place where people keep to themselves. And as you will be working for the Under-Secretary for War, it would be advisable for you to keep to yourself, too.’

Margaret Melfort gave a very direct and charming smile and, as the older woman leant forward, Iris caught the delicate scent of lily of the valley.

Iris glanced around the room. A painting hanging above the mantelpiece attracted her attention. An oil painting of Lady Melfort’s family, it depicted Lord and Lady Melfort and, presumably, their two sons, standing amongst classical ruins in a desert landscape. All their expressions seemed lifeless, their figures painted in muted tones.

Lady Melfort noticed Iris looking at the painting.

‘My son Edward is the artist. Do you like it, Miss Drummond?’

‘It’s interesting,’ Iris said doubtfully, for the painting seemed too surreal for her logical mind. ‘Did he paint it recently?’

‘Last year.’

‘I wondered, because Muriel isn’t in it.’

‘He found Muriel difficult to pin down. Everyone does.’

‘Why are there broken pillars?’ Iris asked.

‘Edward tells me they symbolize loyalty.’

‘I see.’

‘We are a very loyal family, you know, Miss Drummond. It’s important in these uncertain times for blood to be thicker than water.’ Suddenly Margaret Melfort asked abruptly, ‘How did you hear of the job?’

‘I saw it advertised in The Times.’

A parlour-maid entered and began to clear away the plates.

‘My husband has left clear instructions for you in the library,’ Lady Melfort said. Then she added distractedly, ‘Please don’t let Xavier give you anything extracurricular.’

‘I’ll try not to,’ Iris replied, puzzled.

Lady Melfort stood up and Iris realized she had been dismissed.

‘Just before you go,’ Lady Melfort continued, ‘I’m afraid there was some kind of misunderstanding over breakfast. The people who work for my husband tend to eat in the kitchen with the other servants. Or you can eat alone in your room, if you prefer.’

Iris left the bright drawing room to find herself in one of the dark corridors of the castle, and bumped into a figure who had been standing just behind the door. She looked up to see a man in his mid-thirties smiling down at her. He was thin and tall – he looked as if his face had been sculpted away. There was something old-fashioned and poetic about him, and that undefinable quality, charm, hung about him like musk. He moved in a feline way, yet without appearing to be in any way sensual. His pale brown hair was swept back from his face and his eyes seemed large and luminous in the dark.

‘Hello. I don’t think we have been introduced. I’m Louis.’ He had the same languorous phrasing as his mother, but she noticed that his long white fingers were twitching nervously.

‘I’m Miss Drummond, your father’s new secretary.’

‘Ah yes. There have been rumours about you.’

‘Good ones, I hope.’

‘I couldn’t say . . . Anyway, I don’t think there’s going to be much for you to do. My father is hardly ever here.’ He didn’t meet her eyes. There was something about Louis that gave Iris the odd feeling that he wasn’t quite there, as if his old character had left him and this thin cut-out was all that remained. Nor, since she had entered the castle, had the unreality of her situation quite left her.

‘If you’ll excuse me, could you tell me the way to the library?’

Louis simply pointed down the hallway to the door at the end.

The library was a pleasant room lined with mahogany panelling, and overlooked the avenue to the lodge rather than the courtyard and the gardens. There were two desks facing each other, the larger one clearly belonging to Lord Melfort, the other – on which her instructions for the next week or so lay – for his private secretary. She spent the day typing letters and filing various documents. It was only when she worked, Iris thought, that she felt at one with the world around her.

3

OVER THE FOLLOWING weeks, Iris gradually relaxed into the daily routine of the castle. It was a kind of Eden here: Eden before the fall; a paradise, with its extensive gardens and its enclosed formality within the wildness of the surrounding countryside. The castle seemed to offer culture and civilization whereas what had happened to Daphne, Iris thought, must have had a wild and primitive source. There had been a fall here: a terrible fall.

Iris chose to eat alone in her room, rather than with the other servants. The food at the castle was always of the highest quality. There was no need for rationing, as the estate was largely self-sufficient. The family lived on the deer, pheasant and hare they shot, as well as the fresh salmon and trout they caught from the river. The choicest fresh vegetables were plucked from the ground, the sweetest fruit picked from the vines or orchards. Freshly-baked bread came straight out of the kitchen’s ovens. Even chocolate and coffee were smuggled in, in plentiful supply. The servants either shared in the bounty, or enjoyed the various remains.

During a rainstorm that drenched the skies, Lord Melfort returned to Glen Almain. Iris was summoned to the library where she found an elderly man, lost in thought at his desk. He was like the large oak tree outside his window, she decided: sturdy and definite. Its branches and leaves were clearly-defined, reaching outwards and upwards, a powerful emblem of duty and responsibility.

Having introduced himself, he spoke slowly and carefully while she took the dictation of some rather dull ministerial letters. He then instructed her on how to fend off the press and protect him from people he did not want to deal with.

That afternoon, after being dismissed for the day, Iris looked out of the window to see that the sky had lightened and the rain had stopped. She hurriedly put on her raincoat and stepped outside into the fresh air with a sense of relief. She walked along the avenue until she reached the road that ran along the top of the glen. A rough grassy path led off it, down to the river which threaded through the bottom of the glen. As she skirted a steep cliff on her left, a distant roar like the sound of anger began to fill her head. It was the sound of a waterfall which, as she approached, seemed to replace all of her thoughts with its noise.

She entered a glade and gazed up at the waterfall. The sound flooded out of the glade with a thunderous rushing. Swollen with the deluge of rain, the waterfall tumbled down with ferocity into a large pool below, seeming to crush everything beneath its force. Amidst a morass of swirling foam, the pool was churned up into a fury of water.