14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

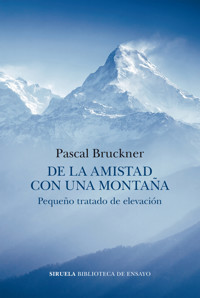

Why are we fascinated by mountains? These outcrops of rock were once considered unsightly, something to be avoided at all costs, but, since Rousseau, they have been contrasted with our corrupt cities and viewed as serene enclaves of beauty and relaxation. But why climb to the summit only to come back down again? Why does the toil of climbing convert into joy? What metaphysics of the absolute is playing out here - what challenge does climbing pose to time and ageing, to fearful panic, to the brush with danger which leads to conquest? It's not faith that elevates mountains - it's mountains that elevate our faith in challenging us to overcome them. These hooded majesties crush some people while exalting others. For the latter, climbing means being born again, reaching a state of exhilaration. Being seized by exhaustion upon arriving at the summit is akin to casting your eyes upon paradise. Is it the stinging cold, the wind so strong that it almost knocks you down, or is it higher powers that speak to us in this mixture of terror and beauty? A child of the mountains who spent his youth in Austria and Switzerland, Pascal Bruckner has special ties to the subject of this book: the further he climbs, the more he reconnects to his past. In sparkling and sensual prose, Bruckner's paean to the majesty of mountains weaves together things seen and things read, childhood memories, literature and philosophy, interlaced with reflections on life, ageing and the unrivalled beauty of an ecosystem that we are in danger of destroying.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 233

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Quote

Preamble: The Test of the Coconut Tree

Notes

1 Where Goes the White When Melts the Snow?

Notes

2 Why Climb?

Notes

3 Our Universal Mother

Notes

4 The Mesmerizing Confederation

Notes

5 The Show-Offs and the Yokels

Notes

6 Lived Experiences

Notes

7 The Aesthetics of the Adventurer: Princes and Peasants

Notes

8 The Two Faces of the Abyss

Notes

9 Reynard and Isengrim

Notes

10 Loving What Terrifies Us

Notes

11 Death in Chains?

Notes

12 Protecting the Great Stone Books

Notes

13 Sublime Chaos

Notes

Epilogue: Once You’ve Reached the Summit, Keep Climbing

Notes

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

vi

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

The Friendship of a Mountain

PASCAL BRUCKNER

A Brief Treatise on Elevation

Translated by Cory Stockwell

polity

Copyright Page

Originally published in French as Dans l’amitié d’une montagne. Petit traité d’élévation © Éditions Grasset & Fasquelle, 2022

This English edition © Polity Press, 2023

Excerpt from Michel Tournier, Célébrations © Mercure de France, 1999. Included with permission of the publisher.

Excerpt from L’Os à Moelle, by Pierre Dac © Presses de la Cité, 2007, 2020 for the current edition. Included with permission of the publisher.

Excerpt from Sid Marty, ‘Abbot’, Headwaters, © McClelland and Stewart, Toronto 1973. Included with permission of the author.

Excerpt from Mountains of the Mind: A History of a Fascination, by Robert MacFarlane © Granta Books, 2003. Used with permission of the publisher.

Excerpt from Mountains of the Mind: How Desolate and Forbidding Heights Were Transformed into Experiences of Indomitable Spirit, copyright © 2003 by Robert Macfarlane. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

111 River Street

Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5553-6 – hardback

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022948504

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Dedication

To the memory of my friend Laurent Aublin (1949–2009), who introduced me to Asia and to climbing at high elevations. His benevolent spirit continues to accompany me on every path, at every summit.

For Anne, in memory of the ascent of the Aiguille du Tour.

Acknowledgements

The expression The Friendship of a Mountain is taken from a novel by Jean Giono.

First and foremost, I’d like to thank Jean-Pierre Aublin and his brother Norbert, who hosted me for many years in Boucher, near L’Argentière in the Hautes-Alpes, for all the unforgettable moments.

I’d also like to thank Françoise and Hugues Dewavrin, whose gourmet hospitality in their chalet in Megève brightens our winters and our summers.

A huge and friendly nod to François Leray for his sense of pedagogy, his patience, and his true guide’s loyalty.

A special nod to Frédéric Martinez in remembrance of the Écrins and the Pointe Percée.

A warm nod to Brieuc Olivier, the hermit of Bettex who every day clinks glasses with Mont Blanc.

A nod also to my faithful climbing companions Manuel Carcassonne, Serge Michel, and Pierre Flavian.

Finally – last but not least – a tender thought for my daughter Anna, who has been trudging about with her papa for so many years.

Quote

He who is not capable of admiration is contemptible. No friendship is possible with him, for there is only friendship in the sharing of common admiration. Our limits, our shortcomings, and our small-mindedness are all healed when the sublime bursts forth before our eyes.

Michel Tournier

Preamble: The Test of the Coconut Tree

Some time ago, I undertook, alongside a climbing companion, Serge Michel, the short ascent of Mount Thabor, which peaks at 3,171 metres. Thabor, which means pious in Aramaic, is also a site of pilgrimage on the French–Italian border, in the Hautes-Alpes. The chapel of Notre-Dame des Sept Douleurs, a solidly built if rather dilapidated building, stands at the summit, and embodies, for the believers, a distinctive site that is linked to the passion of the Christ. When you go there, you come across Buddhists in the lotus position, sitting right in the wind, seeking communion with the cosmos. Having left at about 11 o’clock from the Névache valley, we climbed across firns and screes, a task made all the more difficult by the August heat, which scorched us until we got above 2,500 metres. When we arrived at our destination late in the afternoon, and stood on the knoll at the summit that is covered in Tibetan flags, Serge said to me: ‘You’ve done it. You’ve passed the test of the coconut tree.’

‘The test of the coconut tree?’

‘In certain tribes, the elderly are forced to take a test each year. They have to climb to the top of a coconut tree that the others shake vigorously. Whoever falls is driven out of the village, and goes off to die alone in the jungle. Whoever makes it to the top is allowed to remain in the community.’

Ever since I heard these words, I’ve subjected myself to this test every year, so as to prove that I’m still in the game. There are two mountains I never stop climbing: an internal mountain that fluctuates, in my daily life, between joy and disarray, and an external mountain that confirms or belies the first one.

The descent of Mount Thabor was dangerous: lost on the wrong path, we came upon a herd of sheep, and were attacked by several aggressive sheepdogs. These dogs, which weigh between 90 and 100 kilograms, and which protect sheep and goats from wolves and bears, are extremely dangerous for walkers. It is recommended to avoid looking them in the eye so that the dogs, strong but touchy, don’t think you’re challenging them. Keep a low profile, don’t brandish your walking sticks, look at the ground. We only escaped thanks to a mischievous groundhog who, from the other side of the river, whistled at the beasts, which scampered off after the rodent, determined to tear it to pieces. I recall now that the coconut tree, in Simenon’s work, plays a different role. In a short book in which he sketches the lifestyle of colonizers who went overseas in the 1930s to escape the mediocrity of their home country, he mentions a peculiar use of this tropical tree: on certain Pacific islands, when a woman wants to show a man – above all a foreigner – that she consents to his advances, she climbs to the top of a coconut tree, exposing to her suitor everything he’ll obtain – the sun and the moon – if he makes the effort to follow her up the tree.1 It’s a tradition that demands an effort, and we should reinstate it in our more temperate climates: it would encourage our municipalities to plant more trees in our stifling cities. It would at once prevent harassment and the laying of ever more concrete. Since that day, I’ve thought about the gracefully inclined coconut tree whenever I begin a climb, summoning this exotic tree to accompany me in the heart of the Alps or the Pyrenees.

Why climb when you’re long past the summit of life, when you’re already hurtling down the other side of the mountain? Why force yourself to undergo such ordeals, if not to take from them a joy verging on beatitude? It’s not faith that raises mountains – it’s mountains that elevate our faith in challenging us to overcome them. These hooded majesties crush some people while exalting others. For the latter, climbing means being born again, reaching a state of effervescence. Being seized by exhaustion upon arriving at the summit is akin to casting your eyes upon paradise. The density of the moment draws us in. Is it the stinging cold, the wind so strong that it smacks you and almost knocks you down – or is it higher powers that speak to us in this mixture of terror and beauty?

Notes

1

Georges Simenon,

La Mauvaise Étoile

, Folio-Gallimard, 1938, p. 87.

CHAPTER 1Where Goes the White When Melts the Snow?

The smallest snowstorm on record took place an hour ago in my back yard. It was approximately two flakes. I waited for more to fall, but that was it.

Richard Brautigan, Tokyo Mountain Express1

Do you hear the snow against the window-panes, Kitty? How nice and soft it sounds! Just as if some one was kissing the window all over outside. I wonder if the snow loves the trees and fields, that it kisses them so gently?

Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There2

I was born into life in the continuous haze of flakes that summons forgetting and blissful sleep. Placed in a sanatorium at the age of two, a Kinderheim in the Vorarlberg region of Austria, because I was in the early stages of tuberculosis, I first came into contact with the world in the Alps, more specifically in the Kleinwalsertal, a high-altitude valley that, while officially part of Austria, is in fact an exclave located in Bavaria. Its summits rarely pass 2,500 metres – you have to go to Tyrol for the mountains that approach 4,000 metres. The cold, however, was intense: the winter temperatures of my childhood often plummeted to minus 20 or minus 25 for weeks on end. In the middle of January, the animals – stags, deer, chamois – would come down to lower elevations to visit houses where people would feed them hay. Seeing snow today brings me back to when I wore shorts, or rather Lederhosen (leather pants), and suspenders in the Bavarian style, and a strange little hat reminiscent of a kippa. Now that snow is growing rarer, I’m always very moved when this blessed powder honours us with its presence: I see in it the contours of my past. I spent my childhood in the centre of Europe for the worst possible reasons. My father, a passionate anti-Semite who adulated the Third Reich until his dying day in August 2012, wanted to make me a true Aryan. An engineer who chose to work for Siemens from 1941 until 1945, first in Berlin and then in Vienna, he fled the arrival of the Red Army, which arrived at the gates of the city in April 1945, and took refuge, along with his mistress, in the Vorarlberg, which was under French administration. He would send me there seven years later. Having escaped the pursuit of justice upon his return to Paris in November 1945 thanks to a bureaucratic error, he sought to avenge Germany’s defeat by way of his offspring. My timely illness would allow me to settle his score. Unfortunately for him, I didn’t fulfil his wishes. With my Teutonic family name, I was immediately Judaized in France and considered a Jewish intellectual, to his great despair. As someone who seemed to be resisting his own heritage – playing at being a goy – I entered, in spite of myself and in spite of my father, into the great Mosaic family that he would have liked to wipe out. No sooner did I protest that my background was Catholic than my borrowed identity was thrust back upon me. ‘It’s not a problem if you don’t want to admit it!’ I wonder if my father isn’t laughing at this turn of events from beyond the grave.

Snow is inseparable from the pine tree, that zealous, unbending servant who barely moves, except when it relieves its branches by allowing its surplus of snow to fall. It’s a discreet type of conifer: a green column loaded with thorns that keep us from approaching. It huddles together with its fellow pines, and when it bends in the assaults of the wind or a storm, it holds its boughs tight to its body, focused on its trunk like a greedy man on his treasure. Parsimonious and rustic, it groans as though it were inhabited by a crowd of ghosts who might at any moment arise from the undergrowth. This conifer truly appears to be a worker, carrying its parcels of snow like so many packages – a lackey of great height. It’s a pencil covered in feathers, willing to be martyred every year to become a Christmas tree. We place candles on its branches, and we adorn it with tinsel, ornaments, roasted nuts, and flashing lights. We place piles of multi-coloured, useless gifts at its feet. It is destined to be sacrificed: we chop it down in the hundreds of thousands so it can play a bit part for a few days in apartments or houses. It smells nice at first, but ends up slumping on the sidewalk, before being cut up into pieces and taken to the dump. A massacre, all for the joy of children, whether young or old. A sped-up allegory of human existence. We’ve seen enough of you – now scram. This thrifty resinous tree, austere guardian of mountains, always appears apologetic, wondering what it’s doing there. And as though it hadn’t been sufficiently taken advantage of by humans, today some in France judge it to be too phallic, and want to replace the pine tree – sapin in French, a masculine word – by what they call the sapine, an accessory of ‘Mother Christmas’ that is laid down horizontally rather than erected vertically. The French word, however, lends itself to inappropriate jokes, and highlights what it had sought to obfuscate.3

As soon as I get above 1,000 metres, I breathe better, and I feel a very particular euphoria: the ether intoxicates me, clears my mind, liberates endorphins. Something lifts me above myself. The mountain streams that bellow and overflow their banks invigorate me. I feel like I’m home. Without thinking about it, I divide the world in two: on the one hand, low valleys, and on the other, sparkling heights that lead me to a process of purification. The snow is first and foremost an eraser that wipes away the ugliness of the world, even if ugliness ends up triumphing in the end. Freshly fallen slow is miraculous: it buries the landscape, takes the edge off fences and posts, darkens contours, raises roofs and cornices above their normal levels. It has a very indiscreet way of infiltrating all the places it’s not invited and taking up residence there. The structure of the flake, round, thin, angled, embodies the richness of what is infinitely small. If the sun rises after a night of snowfall, we’re witness to the marvel of the first morning, one that shines and sparkles as though the landscape had been lacquered. Whirlwinds of white dust in shining fantasy worlds burn the eyes and dissolve in halos of light. It’s a finely coated universe that squeaks beneath one’s feet, immobile in the iron fist of the cold. The trees are donned in a thick fur of powder; sombre whispers course through the immense forest that suddenly seems neutralized. The mountains are draped as if for a great procession. The ice is at once a painter and a weaver: it sprinkles the trees with powder and traces a web of frost on the stones and the vegetation. The fields undulate and become expanses of meringue. The blanket of silk calls out to skis, asking them to profane it with their lovely looping traces. As we glide along, we believe ourselves capable of dancing at the surface of things, of transforming slopes into long, smooth ribbons. Falls are weightless, blunted by the thickness of the layer of snow. We come across the hieroglyphs of a chamois or a fox. We take ourselves for elves who are able to scale walls, and for whom the laws of gravity cease to exist. In our weightless state, we liquefy matter; our only soundtrack is the rustle of the tips of our skis.

If we go a little higher, the mountains seem to be coated in candied sugar, like the mountain hut at the dome of the Goûter that a telescope image taken in February 2021 showed literally embossed with several layers of crystals. The lace of such summits, with its cones, pyramids, and puffs, gives forth an entire pâtisserie of cold. The white landscape blinds the one who contemplates it; the light carves the peaks with all the details of a sculpture. So strong are the ultraviolet rays and the glare above 3,000 metres that the snow becomes incandescent. The telephone poles appear varnished, and bristle with little fingers of ice. It’s an entire jewellery store that must be grasped the moment it appears, for it will soon be gone. Window panes, streaked with ice, trace geometrical enigmas. The snow is a shroud – a glorious shroud that enchants what it hides. But scarcely has this fleeting miracle come about than the warmth of the day returns, and the beautiful mounds melt, deflating like soufflés; the fragile porcelain of the landscape cracks, the stalactites drip as though they had a cold, and rivulets stream from the roofs. The sun shines upon the frozen shell, and what was pure and immaculate vanishes.

I remember my excitement the first time I was caught in a snowstorm, on the border between Germany and Austria. I was seven or eight years old, and we were travelling from Lyon, where my parents had settled, to the Kleinwalsertal, where we would spend Christmas. Several vehicles had slid into the ditch, and our little 4CVwas having trouble on the steep climb. It was impossible to distinguish the road from the fields: a single white covering erased the borders between them. We had to undertake the long ascent to get from the city of Oberstdorf, in Bavaria, to the village of Riezlern, in Austria. The 4CV was sliding all over the road, and wound up in a snowdrift as high as a wall, along with other vehicles that were sideways on the highway. My panicked mother pleaded with my father to turn back toward Lake Constance. I should say that I was my mother’s little treasure, and that her love gave me a feeling of indestructible strength, even if she did tend to coddle me. The most difficult thing for an only child is to wean himself from the maternal embrace; the most difficult thing for a mother is to let her child go: both undergo a feeling of being wrenched away, but it’s more difficult for the one who remains and who will never again have this unique feeling of fusion, while the little cherub goes off to wander and frolic. The car refused to go forwards or backwards. We had all been marooned, and we’d have to wait in the cold until morning, when the heaven-sent snowplough and tractor would come to drag us up to the border post. In the meantime, I’d fallen asleep on my mother’s lap, my visions of the discontinuous curtain of flakes having on me the effect of a drug. I swore to myself that one day I’d live under this element’s majestic reign.

Snow doesn’t really fall. It sometimes seems to gush forth from the ground, defying the laws of gravity, scrambling our sense of direction, inverting high and low. Like a waterfall that, with the wind’s effect, seems to climb back up toward its source and push the river back to its origin. This downy substance unfolds in curls, climbing toward the sky in an effort to coat it. It’s breath-taking, and makes us feel as though we’ll be swept away like a wisp of straw. A blizzard can annihilate the landscape in the blink of an eye, rendering it unrecognizable and disorienting its inhabitants. Every time I’m blocked in by snow, which sometimes happens in the Alps or in North America, I’m seized by a peculiar euphoria, almost a trance. I remember long January walks beneath gusts of wind in Montreal, Moscow, and New York: it was as though a furious hand was forcing icy seeds into my throat and eyes. I was coated by flakes as if by flour, suffocating with a clown’s makeup on my face, my eyebrows pressed down by ice, my lips blue, my nose mottled, my nostrils blocked. The snow is an eruption of sharp projectiles that rush toward you horizontally, forcing a path through your lips, working their way into your mouth like sand. Granules of buckshot at point-blank range. You swim in an ocean of white that devours streets and avenues, attacks buildings, piles up in drifts, and sculpts tormented figures on telephone poles. Even though I’ve never been in desperate situations at 3,000 or 4,000 metres, where my mouth begins to freeze and I stop being able to feel my extremities, it seems to me that the howling of a snowstorm is less dangerous than that of a thunderstorm. In a snowstorm, you have the marvellous sensation of being cut off from the world, lost in a bubble far from human concerns. Passers-by are like ghosts in the mist; daylight fades away in a pallid dusk. In the distance you hear the melancholy cry of a groomer or a snowplough, with their multi-coloured blinking lights. As a rule, everything that disturbs the everyday reality of mortals delights me: polar temperatures, the sharpness of the cold, and ice that forms on sidewalks in slippery, viscous trails, forcing people into the delicate movements of a tightrope walker.

The whole charm of winter comes from the muted, hushed sensation that the snow brings about, and that gives rise to cosiness. Snow generally falls in a very gentle way: it’s a noiseless noise made up of a thousand indistinct murmurs. The crystals crackle as they land. Falling snow is like the pallid whispering of words sent down to us from the sky. It adds to the feeling we already get in the mountains, that of being sequestered, and makes climbing all the more impracticable. A new land arises from this welcome storm: the sunken land. While we watch the snow fall, we think of the novel written by the German-Moldavian writer, Stefan Heyder Pontescu, entitled The Little Dead Language. In a high-elevation principality in the heart of Europe, in the middle of a remote and impenetrable mountain range, cut off from the world by the snow for six months of the year, a young princess is dying. A magician assures her father that she will be healed if she is able to see the sea when she gets out of bed. ‘These horrible protuberances weigh on her soul and make her ill.’ But her condition makes travel difficult, if not impossible. So the prince decides to have all the peaks separating his kingdom from the distant sea razed, for hundreds of kilometres. Thus begins the considerable task, one that mobilizes the entire lifeblood of the kingdom. They blow up the first few summits of the range separating the country from its neighbours to the south. In their haste, they overlook safety measures: workers die by the dozen in rock slides, as mountains take their revenge by falling on men. The entire population comes together to save the child, joining in to bring down the cursed mountains. All that can be heard is the noise of pickaxes, bulldozers, dynamite. The debris is piled hurriedly on the only plain of the country, forming a large hill in its own right. Night and day, people live in a cloud of dust that blocks the nasal passages of children, who cough and cry to bring life back to the little princess. When, at the end of five months, the peaks that blocked the view of the sea have all been razed, the workers see an immense lake in the distance whose vast size makes it seem like an ocean, and on which sailboats move about gracefully. Only a single rocky rise still blocks the horizon. Time is short: the princess’s condition is worsening. Everyone gets to work: the king promises huge bonuses to whoever is the first to destroy the obstacle. The last forests are brought down; trenches are dug in the fields of snow; glaciers are cleared; peaks are transformed into hills, hills into rises, and rises into bumps, which are then flattened. Finally, one night, the last proud mound of the chain crumbles in a horrific din. In the morning, the landscape is unrecognizable, and in the distance, beyond the still-smoking ruins, shining like an eye on the earth, appears the shimmering surface of a great expanse of water. The child is brought to the top of the castle’s highest tower, and with an astronomer’s telescope she is shown the sea, its beaches, its boats. She smiles in ecstasy, lets out a sob, and dies.