Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Drama Classi

- Sprache: Englisch

Drama Classics: The World's Great Plays at a Great Little Price A classic satire of provincial bureaucracy, which only saw the stage after the personal intervention of Tsar Nicholas I. A small, corrupt Russian town receives a letter informing them of the imminent visit of a government inspector travelling incognito. When a passing civil servant is mistaken for the inspector, panic soon sets in. This English version of Nikolai Gogol's play The Government Inspector, in the Nick Hern Books Drama Classics series, is translated and introduced by Stephen Mulrine.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 172

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DRAMA CLASSICS

THEGOVERNMENTINSPECTOR

byNikolai Gogol

edited and with an introduction byStephen Mulrine

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

For Further Reading

Gogol: Key Dates

Dramatis Personae

Act One

Act Two

Act Three

Act Four

Act Five

Appendix: Pronounciation

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Introduction

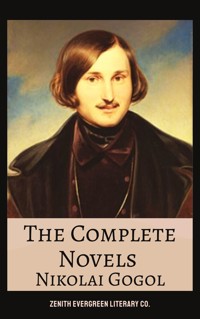

Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol (1809 – 1852)

Gogol was born on March 20th, 1809, at Sorochintsy in the Ukraine. Gogol’s family belonged to the minor Russian-speaking nobility, and his father had some literary pretensions, writing plays based on Ukrainian folk-tales. The young Gogol is said to have shown considerable acting talent at the local high school, from which he graduated in 1828, at the age of nineteen. Intent on a career in the government service, Gogol moved to St. Petersburg, but failed to find employment, either as a civil servant or as an actor.

In July 1829, he attempted to launch a literary career with a sentimental idyll, Hans Küchelgarten, published under a pseudonym, but the work attracted such unfavourable reviews that Gogol bought up all the unsold copies and made a bonfire of them, before leaving for Germany, where he remained until September. On his return to Russia, Gogol’s fortunes took a turn for the better, and in 1831 he succeeded in obtaining a post as a teacher of history in a young women’s college.

In September of that year, Gogol published a collection of tales of Ukrainian village life, Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka, which met with immediate critical acclaim, including that of the great Pushkin himself, and with the appearance of a second volume, in March 1832, Gogol was established as an important new voice.

A career in education still beckoned, however, and although he began work on a comedy, Vladimir Third Class, his pedagogic ambitions were perhaps over-fulfilled with his appointment as assistant professor of history at the University of St Petersburg in July 1834. At any rate, Gogol continued to write, and the following year saw the publication of Arabesques, essays and stories of life in the capital, including Nevsky Prospect, The Portrait, and the extraordinary Diary of a Madman, in addition to another collection centred on his native Ukraine, Mirgorod.

Gogol soon tired of academic life, and his departure from the university in December was crowned by the completion of The Government Inspector, which was given its first performance on April 19th, 1836, at the Aleksandrinsky Theatre in St Petersburg. The play was an instant hit, but Gogol became alarmed at attempts by both left and right-wing critics to turn it into a cause célèbre, and again left the country, settling eventually in Rome, where he remained for the next eleven years, returning to his homeland only twice, to oversee publication of his books.

In 1843, a four-volume collection of his works appeared, which consolidated his fame, and it was during these years of voluntary exile that Gogol’s prose masterpieces were completed: Taras Bulba, Dead Souls, and perhaps his most influential short story, The Overcoat, which would later prompt Dostoevsky to observe: ‘We have all emerged from under Gogol’s overcoat.’

Gogol himself, however, continued to agonize, morally and spiritually, over the purpose of his fiction, and in the summer of 1845 he burned the manuscript of the second volume of Dead Souls, destroying five years’ work. And the following year, the erstwhile hero of the liberals published his notorious Selected Passages from Correspondence with Friends, a reactionary defence of the Tsarist autocracy and serfdom. Again, Gogol was taken aback by the hostility it encountered, including a ferocious diatribe from the radical critic Belinsky, his former champion, and in 1848 he embarked on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, in a vain search for spiritual solace.

In his latter years, after his return to Russia in 1848, Gogol fell prey to religious mania, aggravated by the influence of a fanatical Orthodox priest, Father Matvei, and became chronically ill through dangerous ascetic practices. Towards the end of his life, Gogol was so emaciated that his vertebrae could be felt through his stomach. On February 11th, 1852, in a final act of creative self-immolation, he burned the rewritten second volume of Dead Souls, and died ten days later, from exhaustion and malnutrition, at the age of forty-two.

The Government Inspector: What Happens in the Play

In all essentials, Gogol’s ‘case of mistaken identity’ is a comic warhorse of some pedigree, reaching back to classical times and forward to our own day in seemingly inexhaustible variation. A penniless stranger arrives in a small provincial town, is mistaken for a VIP, treated like royalty by all and sundry, and eventually exposed – making his hosts look extremely foolish. Gogol’s vari ation, on his own evidence, came from Pushkin, in response to a letter he sent to the great poet, seeking a subject for a comedy. Pushkin obliged with an anecdote from his own experience, having himself been mistaken for an important government official, on a trip to the Volga region a few years previously. However, Gogol was also influenced by Corneille and Molière, and perhaps by a Russian comedy on a similar theme by Kvitka, written in 1827, and titled A Visitor From the Capital.

Detail is all-important in Gogol’s work, and The Government Inspector is no exception. Almost the whole of Act One, for example, is devoted to painting a picture of his nameless provincial mudhole, and its corrupt and self-serving administrators, long before the play’s eponymous ‘hero’ makes his entrance, in the squalid inn which is the setting for Act Two.

Khlestakov, the bogus inspector, is in fact a low-grade civil servant, travelling from St Petersburg to his family home – a young man living beyond his means, a follower of fashion, and inveterate card-player, temporarily holed up at the local inn, and unable to pay his bill. However, while Khlestakov and his manservant Osip debate where their next meal is to come from, the town mayor is at that moment reading out the contents of a letter to an urgently convened assembly of local officials and dignitaries.

The letter warns of an impending visit by a government inspector, travelling incognito, and the anxious officials attempt to plan a strategy for keeping their various swindles under wraps, at least for the duration of the visit. The mayor himself might be described as bribe-taker in chief, preying on the local traders; the judge, obsessed with riding to hounds, treats his court as an extension of his tack-room; the postmaster diligently unseals the mail, and retails its contents as gossip; the charities warden, and a compliant workhouse physician maintain their charges on a régime of strict discipline and no expensive medicaments. Embezzlement is routine, the town is run for private profit, and the officials are further panicked when two local landowners, Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky, burst in to announce that the government inspector, in the person of Khlestakov, is in their very midst!

The mayor promptly leads a delegation to Khlestakov’s inn, settles the latter’s unpaid account, and arranges for his removal to more comfortable quarters, i.e., his own mansion, where Khlestakov, the sophisticated St Petersburg dandy, instantly becomes a focus for the amorous yearnings not only of the mayor’s daughter, but also of his wife. While Khlestakov is enjoying life at the mayor’s house, he receives a series of visits from the guilt-ridden officials, each more eager than the last to purchase his favour, with extravagant ‘loans’.

Word of the inspector’s presence has filtered down to the long-suffering citizenry, however, and a deputation of traders and artisans also arrives with a catalogue of grievances for Khlestakov, accusing the mayor. Siberian exile, at the very least, appears to beckon, but in a neat twist, Khlestakov is inveigled into proposing marriage to the mayor’s daughter. Overcome with relief, now that his position is secure, the mayor envisages a glittering career in St Petersburg. Khlestakov, meanwhile, has yielded to the urgings of his manservant Osip to quit while ahead, and is already miles away by the time the post master unseals his letter to a St Petersburg journalist crony, revealing all.

Finally, just as it seems the nadir has been reached, with the townsfolk’s realisation that they have been willing dupes, a policeman enters with the news that a genuine government inspector has arrived, and is waiting for them at the inn. The mayor and his officials, his wife and daughter, their various guests, all freeze in a dumb show precisely described by Gogol, a literal monument to human greed and folly.

The Government Inspector

Gogol began writing The Government Inspector in the autumn of 1835, and the fact that it received its first performance a mere six months later is itself worthy of note, given the rigours of the Tsarist censorship. (Pushkin, for example, died without ever seeing Boris Godunov performed, and Ostrovsky waited nine years for the first public staging of his satire A Family Affair, with a rewritten ‘moral’ ending, moreover, supplied by the censor.) By good fortune, however, Gogol showed his latest creation to the poet Zhukovsky, who was also tutor to the young Crown Prince, and the play thus came under the Tsar’s personal scrutiny. In a magnanimous gesture of the kind he occasionally permitted himself, Nicholas ordered The Government Inspector to be perfor med at the Aleksandrinsky Imperial Theatre in St Petersburg, and the première duly took place on April 19th, 1836. The Tsar himself was in the audience, expressed his delight, and added: ‘Everyone has received his due, myself most of all.’

Gogol’s brilliant comedy, however, attracted praise and condemnation in equal measure: to the radical intelligentsia, it was a welcome indictment of the corrupt and inefficient Tsarist regime; to the conservatives, it was unpatriotic and subversive. Not for the last time, Gogol was driven to explain his intention, and in a letter to Zhukovsky, he expressed his annoyance that both wings of Russian opinion appeared to see the play as offering a challenge to the established order, whereas his satire was directed only at individuals who took the law into their own hands, in defiance of that order.

In this respect, it is significant that the play’s action, as distinct from its final tableau, concludes with the off-stage arrival of the genuine inspector, who will presumably call the miscreants to heel and re-establish good government. No doubt if Gogol had followed Molière’s example in Le Tartuffe, and furnished his audience with a lengthy disclaimer, he might have spared himself some heartache, but while the play benefits immensely from its steel-trap ending, Gogol was still rationalising his intention some ten years later, when he even proposed an allegorical interpretation. In an essay written in 1846, Gogol claimed that his provincial town in fact symbolised the human spirit, and its various characters represented our ungoverned passions. Khlestakov acted as its conscience, but one itself corrupted by society, while the real inspector stood for the true conscience of man, awakened only at the point of death. This is at some remove from the ‘authentic Russian anecdote’ he begged from Pushkin in 1835, and arguably even further removed from an audience’s actual experience of the play.

However, while we may believe that Gogol’s astonishment at how its first audience interpreted the work was a little naive, he was also angered, with more justice perhaps, by the manner of its performance. Gogol’s characters are embroiled in a farcical siuation, but they are not mere caricatures; they are recognizable human types, their vices exaggerated as dominant character traits, overlaid with a rich patina of detail. Coarse acting, playing to the gallery, can dehumanize them, and that appears to have been the case at its première in 1836, when the key role of Khlestakov, taken by an actor called Dür, was self-consciously played for laughs.

At any rate, Gogol was eventually compelled to write a set of instructions, which are still relevant today. The actor, he says, must first find the ‘common humanity’ of his role, and identify what drives the character. At all costs he must avoid overstatement, and should instead appear almost oblivious of the audience, entirely wrapped up in his own concerns. Essentially, The Government Inspector will take its tone in performance from Khlestakov and the Mayor, and Gogol is at pains to stress that Khlestakov is not a simple impostor, but a virtuoso fantasist, who deludes himself as enthusiastically as he does his provincial hosts. Nor is the Mayor, venal and self-seeking as he may be, a mere scoundrel. Rather, he regards the use of power for personal gain as entirely natural, blind to everything but the main chance.

Gogol accordingly argues for a three-dimensional reading, and this is also clear in his detailed notes on the characters and their costumes:

The Mayor: a man grown old in the service, and in his own way extremely shrewd. Despite his bribe-taking, he conducts himself with dignity; grave in demeanour, even rather sententious; speaks neither loudly or softly, neither too much nor too little. His every word is significant. His features are coarse and hard, someone who has worked his way up from the ranks. Rapid transitions from fear to joy, from servility to arrogance, reveal a man of crudely developed instincts. Routinely dressed in official uniform, with braided facings, top-boots and spurs. Short grizzled hair.

Anna Andreevna: his wife, a provincial coquette of a certain age, educated partly out of romantic novels and album verse, and partly from bustling around, overseeing the pantry and the maids’ room. She is extremely inquisitive, and displays her vanity at every turn. Occasionally has the upper hand over her husband, but only when he is stuck for a reply, and her dominance extends no further than trivial matters, expressed in nagging and mockery. She has four complete changes of costume in the course of the play.

Khlestakov: a young man of about twenty-three, slim-built, almost skinny; a little scatterbrained, with, as they say, not a great deal upstairs; one of those people in government service referred to as ‘nitwits’. Speaks and acts without a thought. Quite incapable of concentrating on any particular idea. His delivery is rather staccato, and he says the first thing that comes into his head. The more naivety and simplicity the actor brings to this role, the more successful he will be. Dressed in the height of fashion.

Osip: his manservant, like the generality of servants who are getting on in years: sober-sided, eyes downcast most of the time; something of a moraliser, fond of repeating little maxims to himself, but for the benefit of his master. His voice is almost always level, but in conversation with Khlestakov occasionally takes on a harsh, abrupt tone, to the point of rudeness. He is more intelligent than his master, and thus quicker on the uptake, but doesn’t say much, and craftily keeps his own counsel. Wears a shabby grey or dark blue coat.

Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky: both men are short and squat and intensely inquisitive; their resemblance to one another is quite extraordinary; both have little pot-bellies, both gabble at high speed, helped along by gestures and hand-waving. Dobchinsky is slightly taller and more sedate than Bobchinsky, but the latter is jollier and more animated.

Lyapkin-Tyapkin: the Judge, a man who has read five or six books and fancies himself a freethinker. Much given to conjecture, he weighs carefully his every word. The actor playing him must maintain a portentous expression at all times. Speaks in a deep bass voice, with a drawling delivery, and a throaty wheeze, like one of those antique clocks that hiss before they strike.

Zemlyanika: the Charities Warden, a rather fat, sluggish and cumbersome person, but a sly rogue nonetheless. Extremely servile and officious.

Postmaster: simpleminded to the point of naivety.

The other roles need no explanation. Their originals can be seen almost everywhere.

The actors should pay close attention to the concluding tableau. The final lines should produce an immediate electrifying effect on all present, and the entire cast mustadopt its new position instantly. A cry of astonishment must erupt from all the women simultaneously, as if from a single pair of lungs. Failure to observe these notes may ruin the whole effect.

One can imagine Gogol’s chagrin at seeing the Khlestakov described above travestied by Dür as a professional confidence trickster, and even though the play was staged the following month in Moscow, with a new cast which included the great Mikhail Shchepkin as the Mayor, the Maly Theatre actors, soon to become skilled interpreters of Ostrovsky, were still too broad for Gogol’s taste. Nonetheless, The Government Inspector speedily entered the permanent repertoire, where it has remained ever since. In 1921, for example, in a key production by the Moscow Art Theatre, directed by Stanislavsky, Mikhail Chekhov (the nephew of Anton) is said to have played Khlestakov as a pathological liar, perhaps closer to Gogol’s ideal.

Other notable Khlestakovs include the American comedian Danny Kaye, in a Hollywood musical adaptation of 1949, and Paul Scofield in a 1966 RSC production, directed by Peter Hall. Ian Richardson recreated the role at the Old Vic in 1979, and more recently, the television comic Rik Mayall played Khlestakov in a National Theatre production, directed by Richard Eyre in 1985.

Since its first staging, however, arguably the most striking production was that of Vsevolod Meyerhold in 1926, using a text enlarged by extracts from Gogol’s prose works, and which lasted four hours. Against a semi-circular array of imposing double doors, Meyerhold divided The Government Inspector up into fifteen episodes, with specially commissioned music, and not only re in forced the play’s pantomime elements, but also its darker satire. For Meyerhold, Gogol’s real target was not an isolated abuse of power in some remote outpost of Nicholas I’s empire, but the entire réxgime. Controversial as the production was, not least because of the liberties taken with Gogol’s text, it remained a fixture in the repertoire until 1938, when Stalin ordered the liqui d ation first of Meyerhold’s theatre, then of the director himself.

In his own lifetime, Gogol was never reconciled to his creation, and the allegorical dénouement, which he proposed staging as a sort of epilogue in 1846, was quite properly dismissed by his friends as an aberration. Like all great fiction, Gogol’s masterpiece exhausts interpretation, even that of its creator. Near the end of his life, the author morosely offered his own assessment of what he had achieved:

In The Government Inspector I resolved to gather into one heap everything that was bad in Russia, which I was aware of at that time, all the injustices being perpetrated in those places, and in those circumstances that especially cried out for justice, and tried to hold them all up to ridicule, at one fell swoop. However, as is well known, that produced a tremendous effect. Through the laughter, which I had never before vented with such force, the reader could feel my deep sorrow...

Gogol’s sombre reflections, however, tell us little about the workings of this superbly crafted comedy, which continues to delight audiences everywhere, transcending the limitations of its own period and culture. Nabokov describes it as the greatest play ever written in Russian, and the key to its success perhaps lies in the ‘common humanity’ Gogol attempted to urge on its first clumsy interpreters. In the words of the Mayor, traditionally spoken facing the audience:

‘So what are you laughing at, eh? You’re laughing at yourselves, that’s what!’

The Translation

The American poet William Carlos Williams once observed that: ‘the only true universal resides in the local and particular’, and Gogol’s great universal comedy is intensely specific to its own culture. This is nowhere more obvious than in the complex administrative arrangements of his provincial town, and the translator is thus faced with the problem of finding English equivalents for uniquely Russian institutions.

Among the most important of these is the so-called Table of Ranks. This was a system introduced by Peter the Great in 1722, which classified civil servants into fourteen grades, on a par with commissioned ranks in the military, and virtually everyone, save petty traders and serfs, was positioned on this social ladder. Much of the piquancy of relationships in 19th-century Russian fiction derives from it, and it is interesting to note that Gogol himself, on his arrival in St Petersburg, held the rank of ‘collegiate registrar’, i.e., the 14th grade, equivalent to a cornet or ensign. In The Government Inspector, this is Khlestakov’s rank.

Furthermore, while all ranks were regarded as belonging to the nobility, only the first eight were hereditary, and superiors were addressed in accordance with the precise position they occupied in the hierarchy. In Act III of The Government Inspector, the characters formally introduce themselves by name, post and rank: thus, the Judge is a collegiate assessor, 8th grade, equivalent to a major; the Postmaster is a court councillor, 7th grade, equivalent to a lieutenant-colonel; the Mayor himself, the town’s leading citizen, holds the rank of collegiate councillor, 6th grade, equivalent to a colonel.

In translation, I have generally left these intact, with the occasional exception, and one such occurs in Osip’s Act II