8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Capstone Classics

- Sprache: Englisch

DISCOVER THE INDIGNITIES AND REALITIES OF SLAVERY FROM A CAPTIVATING FIRST-HAND NARRATIVE

Olaudah Equiano’s interesting narrative is an astonishing first-hand account of kidnapping, enslavement and eventual emancipation that has horrified and enlightened readers for over 200 years. The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano is a seminal work in a genre that seeks to help us better shape the present by understanding our violent past.

An insightful Introduction from Atlantic slave trade expert Michael Taylor sheds light on Equiano’s life, including his spiritual conversion, his wide travels, and the impact of his writing on the eventual abolition of slavery.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 451

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

INTRODUCTION

ENSLAVEMENT

WITNESS OF HISTORY

BUSINESS VENTURES AND FREEDOM

EMERGING ABOLITIONIST

THE

NARRATIVE

EQUIANO THE CHRISTIAN

EQUIANO AND ECONOMICS

THE

NARRATIVE'S

IMPACT

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

FURTHER READING

NOTE ON THE TEXT

NOTE

ABOUT MICHAEL TAYLOR

ABOUT TOM BUTLER-BOWDON

LIST OF SUBSCRIBERS

VOLUME I

I

NOTES

II

III

IV

NOTES

V

NOTES

VI

VOLUME II

VII

NOTE

VIII

IX

X

NOTES

XI

XII

NOTES

EXPLANATORY NOTES

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover Page

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

ii

iii

v

vi

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

xxi

xxii

xxiii

xxiv

xxv

xxvi

xxvii

xxix

xxxi

xxxv

xxxvii

xxxviii

xxxix

xl

xli

xlii

xliii

xliv

xlv

xlvi

xlvii

xlviii

xlix

l

1

3

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

33

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

63

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

191

192

193

195

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

221

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

313

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

353

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

Also available in the same series:

Beyond Good and Evil: The Philosophy Classicby Friedrich Nietzsche (ISBN: 978-0-857-08848-2)

Meditations: The Philosophy Classicby Marcus Aurelius (ISBN 978-0-857-08846-8)

On the Origin of Species: The Science Classicby Charles Darwin (ISBN: 978-0-857-08847-5)

Tao Te Ching: The Ancient Classicby Lao Tzu (ISBN: 978-0-857-08311-1)

The Art of War: The Ancient Classicby Sun Tzu (ISBN: 978-0-857-08009-7)

The Game of Life and How to Play It: The Self-Help Classicby Florence Scovel Shinn (ISBN: 978-0-857-08840-6)

The Interpretation of Dreams: The Psychology Classicby Sigmund Freud (ISBN: 978-0-857-08844-4)

The Prince: The Original Classicby Niccolo Machiavelli (ISBN: 978-0-857-08078-3)

The Republic: The Influential Classicby Plato (ISBN: 978-0-857-08313-5)

The Science of Getting Rich: The Original Classicby Wallace Wattles (ISBN: 978-0-857-08008-0)

The Wealth of Nations: The Economics Classicby Adam Smith (ISBN: 978-0-857-08077-6)

Think and Grow Rich: The Original Classicby Napoleon Hill (ISBN: 978-1-906-46559-9)

The Prophet: The Spiritual Classicby Kahlil Gibran (ISBN: 978-0-857-08855-0)

Utopia: The Influential Classicby Thomas More (ISBN: 978-1-119-75438-1)

The Communist Manifesto: The Political Classicby Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (ISBN: 978-0-857-08876-5)

Letters from a Stoic: The Ancient Classicby Seneca (ISBN: 978-1-119-75135-9)

A Room of One's Own: The Feminist Classicby Virginia Woolf (ISBN: 978-0-857-08882-6)

Twelve Years a Slave: The Black History Classicby Solomon Northup (ISBN: 978-0-857-08906-9)

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: The Black History Classicby Frederick Douglass (ISBN: 978-0-857-08910-6)

THE INTERESTING NARRATIVE OF OLAUDAH EQUIANO

The Black History Classic

OLAUDAH EQUIANO

With an Introduction byMICHAEL TAYLOR

This edition first published 2021

Introduction copyright © 2021 Michael Taylor

The material for the Interesting Narrative is drawn from the first edition, published in London in 1789, and in the public domain.

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is Available:

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9780857089137 (hardback)

ISBN 9780857089151 (ePDF)

ISBN 9780857089144 (epub)

INTRODUCTION

By Michael Taylor

In the opening paragraph of his 1789 memoir, the black British abolitionist Olaudah Equiano presents himself as an everyman. ‘I offer here the history of neither a saint, a hero, nor a tyrant’, he tells his readers. ‘I believe there are few events in my life which have not happened to many.’

This is entirely wrong. From his earliest years in ‘a charming fruitful vale’ in what is now Nigeria to his retirement as a gentleman, Equiano lived a life of uncommon drama. His story is reminiscent of the eighteenth century's most imaginative picaresque adventures. If The Interesting Narrative were fiction, it might sit alongside Fielding's Tom Jones or Smollett's Roderick Random as an archetype of the genre – and so it was prescient that Equiano's parents named him ‘Olaudah’ (pronounced Oh-lah-oo-dah), which means ‘vicissitudes or fortunate’.

ENSLAVEMENT

When Spanish and Portuguese merchant-adventurers annexed swathes of the Americas in the sixteenth century, they found that white colonists were unwilling to undertake the back-breaking work needed to cultivate tropical crops. Enslaved African labour became the grotesque lifeblood of the New World economy. By the 1750s, with the French and the British having built their own slave empires, some 50,000 Africans were being enslaved and trafficked across the Atlantic every year.

It was Equiano's misfortune that he was born in the mid-1740s in what was then the kingdom of Benin, a prime hunting ground for European slave traders.1 At the age of 11, a rival nation kidnapped Equiano before selling him to British merchants for the price of 172 ‘little white shells’. When this was paid, he endured ‘six or seven months’ of captivity before arriving at the coast. There he saw the sea for the first time, and a slave ship anchored and awaiting its cargo. Equiano records in the Narrative that these scenes ‘filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror when I was carried on board … I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me’. It is also the first time that Equiano has seen Europeans, and even their appearance alarms him.

Few people have described the horrors of the Middle Passage – that is, the ocean voyage from the African coast to the American colonies – with as much colour and clarity as Equiano. ‘When I looked round the ship and saw a large furnace of copper boiling’, he recounts, ‘and a multitude of black people of every description chained together, every one of their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate’. After weeks on the ocean in the sultry sailing season, with the enslaved crammed every which way into the bowels of the ship, ‘the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victim to the improvident avarice … of their purchasers’. And there were other indignities on such voyages: Equiano would later witness sailors ‘gratify[ing] their brutal passions with females not yet ten years old’.

Unloaded but apparently ‘unsaleable’ in Barbados, Equiano's captors took him to Virginia, where he witnessed plantation slavery for the first time. Weeding plants and gathering stones, loneliness crippled him: he shared no language with the other enslaved Africans, let alone the colonists. Even indoors, where enslaved people could expect a less gruesome life, he was shocked at how black women were clapped in iron muzzles while cooking dinner for the planters. Here, Equiano was called Jacob; during the Middle Passage, he had been called Michael. Yet when he was purchased by the British naval officer Michael Henry Pascal, and bundled onto a vessel laden with tobacco bound for England, Equiano received yet another name. Gustav Vasa was the sixteenth-century king of Sweden who led his nation to independence from Denmark and, following the success of a London play based on his life, the Swedish monarch had acquired a cult following in Britain. Accordingly, Pascal renamed Equiano in honour of Vasa (misspelling the original name to make him ‘Gustavas Vassa’). It took time for Equiano to assent: ‘When I refused to answer my new name’, he recalled, ‘which at first I did, it gained me many a cuff’.

WITNESS OF HISTORY

In the years that followed, Equiano's story shadows the major events of British history. Upon the outbreak of the Seven Years War, he hunts French ships in the English Channel. He docks at Portsmouth during the court-martial of Admiral Byng, whom the authorities famously executed for failing to defend Minorca from the French. Equiano's ship then ferries the Duke of Cumberland – the Butcher of Culloden – from the Netherlands to London, and in 1758 he and his master Michael Pascal convey General James Wolfe to death and glory in French Canada. Soon afterwards, Equiano sees the British fleet at Gibraltar capture the first fighting Temeraire, the third of which Turner would paint so brilliantly in the 1830s. During all of this, Equiano found the time to convert to Christianity, receiving his baptism at St Margaret's Church in the shadow of Westminster Abbey.

Even after the turmoil of the first truly global war, which ended with the British making enormous gains in Canada and India, the young Equiano continued to collide with the actors and places of the age. He claims to have heard George Whitefield, the Methodist who roused American Christians during the Great Awakening, preach at Philadelphia, although this probably happened at Savannah. Equiano also did business on St Eustatius, the tiny Dutch island in the Caribbean which would prove so pivotal in the American Revolutionary War. There, the riches of its warehouses so distracted the plundering British admiral George Rodney that he could not prevent the French navy from surrounding the British forces so decisively at Yorktown.

BUSINESS VENTURES AND FREEDOM

Despite what Equiano represents as faithful service to Pascal, they did not part on good terms. Equiano had won considerable prize money by boxing against other boys on the decks of ships, but when Pascal sold Equiano to another British officer in Gravesend, he refused to pay up. Indeed, when they chanced upon each other in later years, Pascal told Equiano that he would not have yielded a penny even if Equiano had won £10,000 by fighting.

Upon being sold once more – this time to the merchant Robert King, a Philadelphian who traded in the West Indies – Equiano spied a chance for redemption and freedom. Earning the trust of King and his shipmates, with whom he darted about the Caribbean on King's business, Equiano began to sell goods and earn money in his own right. By 1765 he had acquired £40, more than £7,000 in today's money, and this was enough to persuade King, however reluctantly, to permit Equiano to purchase his own freedom. Equiano even had £8 spare to buy a sparkling ‘super-fine’ light blue suit ‘to dance in at my freedom’.

What would he do with his newly earned liberty? Equiano does not quite know which path to follow. At first, he returns to what he knows, merchant sailing, and there follows the dramatic shipwreck of the sloop Nancy in the Bahamas, where in his judgment only Providence saved him from drowning or dying of thirst. Taking leave of the Americas, Equiano returns to London and, besides learning to play the French horn, takes up an apprenticeship in hairdressing at Haymarket. This does not suit the restless sailor, who again goes to sea. Now cruising the Mediterranean, he embarks on the mercantile equivalent of the Georgian era's Grand Tour: from Savoyard Nice to Tuscan Livorno – or as the British called it, Leghorn – and then to Ottoman Smyrna on the Aegean coast. Equiano even takes in the grand opera at Naples, where the eruption of Vesuvius in 1769 sprinkles ash on the deck of his ship.

By 1773, Equiano was ready for an altogether more expansive mission, enlisting on HMS Racehorse for an exploratory voyage to the Arctic in search of the elusive north-eastern passage to India. Led by Constantine Phipps – whose descendant, as governor of Jamaica, would do much to hasten the abolition of slavery in that colony – the journey produces one of the first English-language descriptions of polar bears, of which Equiano claims the crew killed nine. Having escaped the drifting ice packs which sundered many a ship beyond Svalbard, Equiano's next adventure takes him to the Mosquito Coast, the Caribbean shoreline which stretches along present-day Nicaragua and Honduras. Perhaps surprisingly, Equiano had gone into business here with a former shipmate in order to establish a slave plantation. Below we consider further the moral ambiguity of this endeavour.

EMERGING ABOLITIONIST

In 1777, Equiano was back in London, which he had come to regard as ‘home’, and where abolitionism was emerging from the crucible of dissenting Protestant thought. In its earliest years, the abolitionist ‘movement’ operated only in sporadic bursts, often at the prompting of Granville Sharp. The son of a Northumbrian deacon, Sharp had rescued African teenager Jonathan Strong from deportation to Jamaica in 1765 before intervening in the Somerset litigation of 1772–73. Here, the issue before the English courts concerned the ability of a planter to re-enslave a person, in this case the freed black man James Somerset, on British soil. Although Lord Mansfield ruled in time in Somerset's favour, it was not the sweeping condemnation of slaveholding that so many had wanted. The Morning Chronicle described the judgment as ‘guarded, cautious, and concise’.

In the spring of 1783, Equiano made his first momentous contribution to the abolitionist cause. He delivered some highly disturbing intelligence to Sharp, who was working as a clerk at the Ordnance Office. ‘Gustavus Vasa a Negro’, Sharp wrote in his diary, ‘called on me with an account of 130 Negroes being thrown Alive into the sea from on Board an English Slave Ship.’ (Beyond the authorship of the Narrative, Equiano went almost universally by the name of Vasa.)

The ship in question was the Zong, which in 1781 had set off from the Gold Coast for Jamaica with 442 Africans in its hold. Having mistakenly sailed past Jamaica by several hundred miles, and finding themselves short of drinking water, the crew of the Zong had elected – as Equiano accurately reported – to throw overboard almost one-third of the people they were trafficking. They did so for purely commercial reasons: the insurance law of the day provided nothing if enslaved Africans died of natural causes such as dehydration, but did compensate traders for any ‘cargo’ that they needed to jettison in order to preserve the remainder. It followed that, when the case of the Zong came before the courts, it was not on account of criminal charges; instead, the dispute arose because the insurers refused to pay up. It would take an appeal and the scandalous evidence that the Zong in fact had plenty of water on board for the insurers to win, but Sharp would fail to bring criminal charges against the crew.

Even so, the Zong massacre proved a catalyst for abolitionism. By 1787, the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade had formed under the political leadership of William Wilberforce. Equiano – in alliance with other once-enslaved Britons such as Ottobah Cugoano – established the corresponding society known as the Sons of Africa. Working in tandem, Wilberforce's abolitionists and the Sons of Africa began flooding the London papers with anti-slavery material, constructing mass petitions calling for abolition, and publishing tracts which attacked the slave trade on moral, religious, and even economic grounds. Equiano's pugnacious dispute with pro-slavery interests in the Morning Chronicle brought him ever greater renown.

Equiano had also taken a position with the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor. The Committee had been founded in 1786 to provide assistance to the thousands of black loyalists whose reward for fighting with the Crown against the American revolutionaries was freedom – albeit a freedom which often left them languishing on the streets of London. Almost immediately, the Committee set about resettling these black loyalists to Sierra Leone, the new British colony on the coast of Guinea. Appointed as a commissary with responsibility for ‘provisions and stores’, Equiano's time with the Sierra Leone project would end in ignominy – he was dismissed after complaining about the colony's financial mismanagement. But it was in this context of increasing public engagement with the slavery issue that, in 1789, he wrote and published the Interesting Narrative.

THE NARRATIVE

Equiano's Narrative was not published into a vacuum; nor did he publish his autobiography as an unknown. On the contrary, he wrote with the political and financial support of many significant figures in British society who demonstrated that support by subscribing to the first edition; that is, they committed to buy a copy and paid the price up-front, so that Equiano could live upon these early proceeds as he concentrated on writing. Many of the Narrative's subscribers (listed at the start of the book) will be familiar to even casual students of Georgian history: the Prince of Wales, the future Prince Regent and George III; the (Grand Old) Duke of York; the abolitionists Thomas Clarkson and James Ramsay; the author Hannah More and the businessman Josiah Wedgwood; founder of Methodism John Wesley; and a healthy dose of MPs and peers besides. Into their hands Equiano now placed the most affecting account of enslavement – and African intelligence and ingenuity – which had been written.

As the opening passages of the Narrative make clear, slavery was nothing new to Equiano. At home in Benin, the houses of masters and their slaves made up the towns and villages. Equiano's own father had been a slaveholder, and the local slave trade was frequently the cause of ‘irruptions of one little state or district into another’. Yet in Equiano's view there were plain differences between African slavery and that into which Europeans forced him and so many millions of others. For one thing, Equiano almost appears to regard African enslavement as justifiable. ‘Sometimes indeed we sold slaves to them’, he writes of his neighbours, ‘but they were only prisoners of war, or such among us who had been convicted of kidnapping, or adultery, and some other crimes, which we esteemed heinous.’ In short, slavery was dependent on the character of the person, not their skin colour. ‘But how different was their condition from that of the slaves in the West Indies!’ Equiano exclaims. ‘With us they do no more work than other members of the community, even their masters; their food, clothing and lodging were nearly the same as theirs … Some of these slaves have even slaves under them as property, and for their own use.’

This contrasted sharply with what Equiano experienced at the hands of British slave traders. Just as Mary Prince would later educate British readers on the atrocities inflicted upon enslaved people in the West Indies of the 1820s, Equiano gave the readers of the 1780s a painful and often shocking account of the odious commerce. ‘Slaves are sometimes, by half-feeding, half-clothing, over-working and stripes, reduced so low’, he lamented, ‘that they are turned out as unfit for service, and left to perish in the woods, or expire on a dunghill.’ This hatred of slavery would not, however, prevent Equiano from buying enslaved people to work on the plantation that he sought to establish on the Mosquito Coast. Moreover, when Equiano eventually abandoned the project it was not because this apparent toleration of slavery had expired. Rather, it was because he disliked the lifestyle: ‘our mode of procedure and living in this heathenish form’ he writes, was ‘very irksome’.

EQUIANO THE CHRISTIAN

Besides slavery, the second great theme of the Narrative is Christianity. As such, it falls squarely within the genre of spiritual autobiography, and Equiano sought explicitly to immerse himself in the same religion that was practised by his readers. Though his faith was no doubt sincere (he fondly recalls his conversion and later baptism in the year 1759), it was also a rhetorical device to remind his readers that all Africans, such as he, were capable of Christian piety and British civility. Perhaps of even more relevance, Equiano's Christianity was pointedly Protestant and often hostile to Catholicism. When sailing the Mediterranean, for instance, he decries the Portuguese Inquisition and its prohibition of lay readership of the Bible. He is equally unimpressed with Catholic rituals in Porto: ‘I had a great curiosity to go into some of their churches’, he writes, ‘but could not gain admittance without using the necessary sprinkling of holy water at my entrance … I therefore completed this with ceremony, but its virtues were lost on me, for I found myself nothing the better for it’.

Along the coast at Malaga he despairs of bullfighting, but not of its barbarity: rather, the offence is the performance ‘on Sunday evenings’. It was therefore easy for Equiano to spurn the advances of Father Vincent, a ‘popish priest’ [sic] as he put it, who wished Equiano to study in a Spanish seminary. Writing for his mostly Protestant audience, Equiano ‘could not in conscience conform to the opinions of his Church’. However, this Protestantism was heartfelt. When preaching to the peoples of the Mosquito Cost, Equiano took with him that canon of anti-Catholic fervour, Foxe's Book of Martyrs, replete with its gruesome woodcuts of ‘papal cruelties’ that were inflicted upon Reformed Christians in the sixteenth century. It would be wrong to ascribe this explicit Protestantism as a function of religious bigotry. More likely, it was another device to make plain Equiano's acquired Britishness: before the Jacobin espousal of deism in the 1790s, Britons defined Frenchmen by way of their Catholicism as much as their absolutism, and it followed that any good Briton was an equally good Protestant.

Equiano makes frequent references to the Israelites of the Old Testament. In the first chapter, he writes of ‘the strong analogy which … appears to prevail in the manners and customs of my country and those of the Jews, before they reached the Land of Promise’. Later, when first reading the Bible itself, Equiano is struck by the similarity of the Levitical exegeses to the customs of his homeland. The liberation of enslaved Africans seems to him the natural sequel to the exodus from Egypt and the escape from Babylon; just as songs of sweet chariots resounded in the fields of the antebellum South, the victims of British slavery imagined themselves as Israelites awaiting freedom. It was not coincidence that, on the body of Quamina Gladstone, the leader of the 1823 enslaved uprising in Demerara, the British authorities reportedly found a Bible marked at Joshua 8:1: ‘Take all the people of war with you, and rise’.

Equiano's equation of British slaves with the Jews of Exodus also played into the contemporary fashion to imagine Britain itself as the heir of Israel. Handel's oratorios for George II were based on the legends of Esther, Deborah, and Zadok the Priest; pamphleteers celebrated the British victory over the French in the Seven Years’ War as the triumph of the Israelites over the Moabites; and even the radical William Blake wrote of founding a new Jerusalem. Most happily of all, for Equiano these Biblical comparisons could merge in patriotic abolitionism.

EQUIANO AND ECONOMICS

The Narrative contains plenty of nods and winks to the prevailing intellectual fashions of the age. One of these is stadial theory, which was favoured by Equiano's contemporary, the Scottish founder of modern economics, Adam Smith. The theory held that all societies passed through four stages of development, from hunting and gathering through pastoral then arable farming, to commercial trading. This arc is apparent in Equiano's own progress through life.

Economic thinking also finds expression in Equiano's comments on the effects of European commerce. He recognises, for instance, that wars among African nations were often incited ‘by those traders who brought the European goods … amongst us’, and he rues that ‘such a mode of obtaining slaves in Africa is common’. The economic imbalance to these transactions was palpable: ‘When a trader wants slaves’, Equiano continues, ‘he applies to a chief for them, and tempts him with his wares. It is not extraordinary if … he accepts the price of his fellow creatures’ liberty with as little reluctance as the enlightened merchant’.

Equiano wrote to the President of Britain's Board of Trade to encourage the extension of its imperial market into Africa, and the closing passages of the Narrative explore the possibility of ‘legitimate commerce’ acting as an economic means of eradicating the slave trade. If British merchants would trade in African manufactures and not in people, the thinking went, the prime incentive to enslave would dissipate. ‘A commercial intercourse with Africa’, Equiano writes, ‘opens an Inexhaustible source of Wealth to the manufacturing Interest of Great Britain; and to all which the slave trade is an objection.’ In other words, Equiano was a promoter of free trade; his own activity as a trader had helped him buy his freedom.

Finally, there is also in the Narrative more than a hint of the Smithian economics that would inform Thomas Malthus's ideas about economics and population: ‘If the blacks were permitted to remain in their own country’, Equiano says, ‘they would double themselves every fifteen years’.

THE NARRATIVE'S IMPACT

Initial reviews of the Narrative in the British periodical press – the great engine of enlightened public discourse – were mixed.

The Monthly Review of June 1789 believed that the work of ‘this very intelligent African’ was well calculated to ‘increase the odium that has been excited against the West-India planters’. Yet the reviewer cannot quite believe that an African was capable of writing a book: ‘It is not improbable that some English writer has assisted him in the compilement of his book; for it is sufficiently well-written’. The General Magazine and Impartial Review praised the text's ‘truth and simplicity’, finding that ‘the author's account of the manners of the natives of his own province [was] interesting and pleasing’.

Several reviewers agreed that Equiano's meditations on Christianity were weak and, frankly, boring, and among them was the radical philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft. Writing under a pseudonym in the Analytical Review, she finds Equiano's descriptions of brutality so powerful as to ‘make the blood turn in its course’. Yet she also finds ‘the long account of his religious sentiments and conversion to methodism quite tiresome’. Wollstonecraft concludes that ‘a few well written periods’ could not elevate the Narrative beyond the ordinary: Equiano's volumes did ‘not exhibit extraordinary intellectual powers’, and merely placed him ‘on a par with the general mass of men, who fill the subordinate stations in a more civilised society than that which he was thrown into at birth’. In the same vein, Richard Gough in the Gentleman's Magazine concluded that the second volume of the Narrative, which begins after Equiano's manumission and often devolves upon his spirituality, was ‘uninteresting, and his conversion to methodism oversets the whole’.

Notwithstanding the critics, the Narrative sped through ever more editions on both sides of the Atlantic, and the sympathetic elements of the public hailed Equiano as a political and literary hero; in Ireland alone, one edition sold 1900 copies on the back of a wondrously well received speaking tour. (Over 50 years later, the Irish would give a similarly rapturous reception to the formerly enslaved American abolitionist Frederick Douglass.)

This is not to say that the Narrative conferred immediate political benefits on the abolitionist cause. Despite the promise offered by the Dolben's Act of 1788, which imposed the first regulations upon the British slave trade, Wilberforce's efforts to advance abolitionist legislation through Parliament failed repeatedly between 1791 and 1793. There were powerful interests still arrayed in support of slavery, and many in British society were profiting from it. People also felt sympathy for the British Caribbean planters trying to make a living. And when the French Revolutionaries executed Louis XVI and declared total war on monarchist Europe, any political reform which spoke of equality or liberty – let alone fraternity with Africans – was doomed to failure. Indeed, as Pitt the Younger's Tories enacted a series of repressive conservative laws, Equiano himself fell under suspicion both as a member of the radical London Corresponding Society and as a friend of its founder, Thomas Hardy.

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

As the French Revolution convulsed Europe and delayed progress towards abolition for almost fifteen years, Equiano – enriched by his literary success – settled into domestic life. In 1792, he married Susannah Cullen of Soham, Cambridgeshire, and he became father to two daughters: Anna Maria and Joanna. Tragically, this homely tranquillity would not last. Susanna died in 1796, and Equiano would not long survive her: living in apartments close to London's Tottenham Court Road, he died on 31 March 1797. The death of his elder daughter left Joanna as Equiano's sole heir, and upon her twenty-first birthday she inherited £950, an estate approaching £100,000 in today's money.

Yet Equiano would leave a much grander legacy. In 1807, the British Parliament at last passed the Slave Trade Act, but it was only the start of slavery's abolition. Indeed, in the 1820s, abolitionists and slaveholders fought ferociously over the future of slavery, and Equiano was cited as a key witness in the case for emancipation. As one correspondent of the Mirror Monthly Magazine put it, Equiano had ‘distinguished [himself] as a literary character in this country in modern times’.

The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 further vindicated Equiano, but his greatest legacy is arguably in the United States. His Narrative created a literary template, setting the scene for Frederick Douglass's Narrative … of an American Slave (1845), Solomon Northup's Twelve Years A Slave (1853), and even Booker T. Washington's Up From Slavery (1901). These giants followed in Equiano's footsteps. A man who was prevented from receiving any formal education, and who instead led a life of sea-going and spiritual adventure, ended up founding a new literary tradition.

Travels of Olaudah Equiano, as described in the Interesting Narrative, 1789. Created by Miles Ogborn and Edward Oliver, School of Geography, Queen Mary University of London.

Source: Ogborn (2008) Global Lives: Britain and the World, 1550–1800 (Cambridge University Press).

FURTHER READING

Vincent Carretta,

Equiano the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man

(2005).

Toby Green,

A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution

(2019).

Adam Hochschild,

Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire's Slaves

(2005).

David Olusoga,

Black and British: A Forgotten History

(2016).

Padraic X. Scanlan,

Slave Empire: How Slavery Built Modern Britain

(2020).

Michael Taylor,

The Interest: How the British Establishment Resisted the Abolition of Slavery

(2020)

.

NOTE ON THE TEXT

This edition is based on the text of the first edition, published by Equiano himself in London in 1789. The edition includes Equiano's own footnotes, and the original two-volume structure of the work has been preserved. We have retained his original spellings for the most part.

Explanatory notes appear at the end to help readers decode some of Equiano's references, including names of places or peoples that have since changed. However, many places he refers to (e.g. ‘Barbadoes’) are self-explanatory.

Equiano published a number of later editions of the book, but his alterations were of a minor nature. The

Interesting Narrative

was also published in Dutch, German, and Russian.

NOTE

1

There is some controversy over Equiano's birthplace. His biographer Vincent Carretta has pointed to the fact that the register which records his baptism in London in 1759 records his birthplace as South Carolina, then a British colony. On the other hand, Equiano's descriptions of Igboland in southeastern Nigeria are vivid, suggesting he was indeed from there.

ABOUT MICHAEL TAYLOR

Michael Taylor is a historian of colonial slavery in the British Empire. He is the author of The Interest: How the British Establishment Resisted the Abolition of Slavery (2020). Michael holds a PhD in history from the University of Cambridge, and has been Lecturer in Modern British History at Balliol College, Oxford. He is currently a Visiting Fellow at the British Library's Eccles Centre for American Studies.

ABOUT TOM BUTLER-BOWDON

Tom Butler-Bowdonis the author of the bestselling 50 Classics series, which brings the ideas of important books to a wider audience. Titles include 50 Philosophy Classics, 50 Psychology Classics, 50 Politics Classics, 50 Self-Help Classics and 50 Economics Classics.

As series editor for the Capstone Classics series, Tom has written Introductions to Plato's The Republic, Machiavelli's The Prince, Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations, Sun Tzu's The Art of War, Lao Tzu's Tao Te Ching, and Napoleon Hill's Think and Grow Rich.

Tom is a graduate of the London School of Economics and the University of Sydney.

www.Butler-Bowdon.com

THE INTERESTING NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE OF OLAUDAH EQUIANO, OR GUSTAVUS VASSA, THE AFRICAN.

Written by Himself.

Behold, God is my salvation; I will trust and not be afraid, for the Lord Jehovah is my strength and my song; he also is become my salvation. And in that shall ye say, Praise the Lord, call upon his name, declare his doings among the people.Isaiah xii. 2, 4.

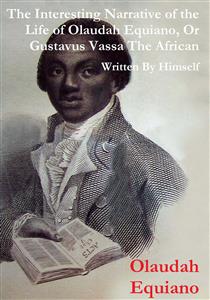

Olaudah Equiano. Frontispiece to second edition of the Interesting Narrative, London 1789 (British Library)

To the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and the Commons of the Parliament of Great Britain.

My Lords and Gentlemen,

Permit me, with the greatest deference and respect, to lay at your feet the following genuine Narrative; the chief design of which is to excite in your august assemblies a sense of compassion for the miseries which the Slave-Trade has entailed on my unfortunate countrymen. By the horrors of that trade was I first torn away from all the tender connexions that were naturally dear to my heart; but these, through the mysterious ways of Providence, I ought to regard as infinitely more than compensated by the introduction I have thence obtained to the knowledge of the Christian religion, and of a nation which, by its liberal sentiments, its humanity, the glorious freedom of its government, and its proficiency in arts and sciences, has exalted the dignity of human nature.

I am sensible I ought to entreat your pardon for addressing to you a work so wholly devoid of literary merit; but, as the production of an unlettered African, who is actuated by the hope of becoming an instrument towards the relief of his suffering countrymen, I trust that such a man, pleading in such a cause, will be acquitted of boldness and presumption.

May the God of heaven inspire your hearts with peculiar benevolence on that important day when the question of Abolition is to be discussed, when thousands, in consequence of your Determination, are to look for Happiness or Misery!

I am,My Lords and Gentlemen,Your most obedient,And devoted humble Servant,OLAUDAH EQUIANO,orGUSTAVUS VASSA.

Union-Street, Mary-le-bone,March 24, 1789.

LIST OF SUBSCRIBERS

His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales.

His Royal Highness the Duke of York.

A

The Right Hon. the Earl of Ailesbury

Admiral Affleck

Mr. William Abington, 2 copies

Mr. John Abraham

James Adair, Esq.

Reverend Mr. Aldridge

Mr. John Almon

Mrs. Arnot

Mr. Joseph Armitage

Mr. Joseph Ashpinshaw

Mr. Samuel Atkins

Mr. John Atwood

Mr. Thomas Atwood

Mr. Ashwell

J.C. Ashworth, Esq.

B

His Grace the Duke of Bedford

Her Grace the Duchess of Buccleugh

The Right Rev. the Lord Bishop of Bangor

The Right Hon. Lord Belgrave

The Rev. Doctor Baker

Mrs. Baker

Matthew Baillie, M.D.

Mrs. Baillie

Miss Baillie

Miss J. Baillie

David Barclay, Esq.

Mr. Robert Barrett

Mr. William Barrett

Mr. John Barnes

Mr. John Basnett

Mr. Bateman

Mrs. Baynes, 2 copies

Mr. Thomas Bellamy

Mr. J. Benjafield

Mr. William Bennett

Mr. Bensley

Mr. Samuel Benson

Mrs. Benton

Reverend Mr. Bentley

Mr. Thomas Bently

Sir John Berney, Bart.

Alexander Blair, Esq.

James Bocock, Esq.

Mrs. Bond

Miss Bond

Mrs. Borckhardt

Mrs. E. Bouverie

–– Brand, Esq.

Mr. Martin Brander

F.J. Brown, Esq. M.P. 2 copies

W. Buttall, Esq.

Mr. Buxton

Mr. R.L.B.

Mr. Thomas Burton, 6 copies

Mr. W. Button

C

The Right Hon. Lord Cathcart

The Right Hon. H.S. Conway

Lady Almiria Carpenter

James Carr, Esq.

Charles Carter, Esq.

Mr. James Chalmers

Captain John Clarkson, of the Royal Navy

The Rev. Mr. Thomas Clarkson, 2 copies

Mr. R. Clay

Mr. William Clout

Mr. George Club

Mr. John Cobb

Miss Calwell

Mr. Thomas Cooper

Richard Cosway, Esq.

Mr. James Coxe

Mr. J.C.

Mr. Croucher

Mr. Cruickshanks

Ottobah Cugoano, or John Stewart

D

The Right Hon. the Earl of Dartmouth

The Right Hon. the Earl of Derby

Sir William Dolben, Bart.

The Reverend C.E. De Coetlogon

John Delamain, Esq.

Mrs. Delamain

Mr. Davis

Mr. William Denton

Mr. T. Dickie

Mr. William Dickson

Mr. Charles Duly, 2 copies

Andrew Drummond, Esq.

Mr. George Durant

E

The Right Hon. the Earl of Essex

The Right Hon. the Countess of Essex

Sir Gilbert Elliot, Bart. 2 copies

Lady Ann Erskine

G. Noel Edwards, Esq. M.P. 2 copies

Mr. Durs Egg

Mr. Ebenezer Evans

The Reverend Mr. John Eyre

Mr. William Eyre

F

Mr. George Fallowdown

Mr. John Fell

F.W. Foster, Esq.

The Reverend Mr. Foster

Mr. J. Frith

W. Fuller, Esq.

G

The Right Hon. the Earl of Gainsborough

The Right Hon. the Earl of Grosvenor

The Right Hon. Viscount Gallway

The Right Hon. Viscountess Gallway

–– Gardner, Esq.

Mrs. Garrick

Mr. John Gates

Mr. Samuel Gear

Sir Philip Gibbes, Bart. 6 copies

Miss Gibbes

Mr. Edward Gilbert

Mr. Jonathan Gillett

W.P. Gilliess, Esq.

Mrs. Gordon

Mr. Grange

Mr. William Grant

Mr. John Grant

Mr. R. Greening

S. Griffiths

John Grove, Esq.

Mrs. Guerin

Reverend Mr. Gwinep

H

The Right Hon. the Earl of Hopetoun

The Right Hon. Lord Hawke

Right Hon. Dowager Countess of Huntingdon

Thomas Hall, Esq.

Mr. Haley

Hugh Josiah Hansard, Esq.

Mr. Moses Hart

Mrs. Hawkins

Mr. Haysom

Mr. Hearne

Mr. William Hepburn

Mr. J. Hibbert

Mr. Jacob Higman

Sir Richard Hill, Bart.

Reverend Rowland Hill

Miss Hill

Captain John Hills, Royal Navy

Edmund Hill, Esq.

The Reverend Mr. Edward Hoare

William Hodges, Esq.

Reverend Mr. John Holmes, 3 copies

Mr. Martin Hopkins

Mr. Thomas Howell

Mr. R. Huntley

Mr. J. Hunt

Mr. Philip Hurlock, jun.

Mr. Hutson

J

Mr. T.W.J. Esq.

Mr. James Jackson

Mr. John Jackson

Reverend Mr. James

Mrs. Anne Jennings

Mr. Johnson

Mrs. Johnson

Mr. William Jones

Thomas Irving, Esq. 2 copies

Mr. William Justins

K

The Right Hon. Lord Kinnaird

William Kendall, Esq.

Mr. William Ketland

Mr. Edward King

Mr. Thomas Kingston

Reverend Dr. Kippis

Mr. William Kitchener

Mr. John Knight

L

The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of London

Mr. John Laisne

Mr. Lackington, 6 copies

Mr. John Lamb

Bennet Langton, Esq.

Mr. S. Lee

Mr. Walter Lewis

Mr. J. Lewis

Mr. J. Lindsey

Mr. T. Litchfield

Edward Loveden Loveden, Esq. M.P.

Charles Lloyd, Esq.

Mr. William Lloyd

Mr. J.B. Lucas

Mr. James Luken

Henry Lyte, Esq.

Mrs. Lyon

M

His Grace the Duke of Marlborough

His Grace the Duke of Montague

The Right Hon. Lord Mulgrave

Sir Herbert Mackworth, Bart.

Sir Charles Middleton, Bart.

Lady Middleton

Mr. Thomas Macklane

Mr. George Markett

James Martin, Esq. M.P.

Master Martin, Hayes-Grove, Kent

Mr. William Massey

Mr. Joseph Massingham

John McIntosh, Esq.

Paul Le Mesurier, Esq. M.P.

Mr. James Mewburn

Mr. N. Middleton,

T. Mitchell, Esq.

Mrs. Montague, 2 copies

Miss Hannah More

Mr. George Morrison

Thomas Morris, Esq.

Miss Morris

Morris Morgann, Esq.

N

His Grace the Duke of Northumberland

Captain Nurse

O

Edward Ogle, Esq.

James Ogle, Esq.

Robert Oliver, Esq.

P

Mr. D. Parker,

Mr. W. Parker,

Mr. Richard Packer, jun.

Mr. Parsons, 6 copies

Mr. James Pearse

Mr. J. Pearson

J. Penn, Esq.

George Peters, Esq.

Mr. W. Phillips,

J. Philips, Esq.

Mrs. Pickard

Mr. Charles Pilgrim

The Hon. George Pitt, M.P.

Mr. Thomas Pooley

Patrick Power, Esq.

Mr. Michael Power

Joseph Pratt, Esq.

Q

Robert Quarme, Esq.

R

The Right Hon. Lord Rawdon

The Right Hon. Lord Rivers, 2 copies

Lieutenant General Rainsford

Reverend James Ramsay, 3 copies

Mr. S. Remnant, jun.

Mr. William Richards, 2 copies

Mr. J.C. Robarts

Mr. James Roberts

Dr. Robinson

Mr. Robinson

Mr. C. Robinson

George Rose, Esq. M.P.

Mr. W. Ross

Mr. William Rouse

Mr. Walter Row

S

His Grace the Duke of St. Albans

Her Grace the Duchess of St. Albans

The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of St. David's

The Right Hon. Earl Stanhope, 3 copies

The Right Hon. the Earl of Scarbrough

William, the Son of Ignatius Sancho

Mrs. Mary Ann Sandiford

Mr. William Sawyer

Mr. Thomas Seddon

W. Seward, Esq.

Reverend Mr. Thomas Scott

Granville Sharp, Esq. 2 copies

Captain Sidney Smith, of the Royal Navy

Colonel Simcoe

Mr. John Simco

General Smith

John Smith, Esq.

Mr. George Smith

Mr. William Smith

Reverend Mr. Southgate

Mr. William Starkey

Thomas Steel, Esq. M.P.

Mr. Staples Steare

Mr. Joseph Stewardson

Mr. Henry Stone, jun. 2 copies

John Symmons, Esq.

T

Henry Thornton, Esq. M.P.

Mr. Alexander Thomson, M.D.

Reverend John Till

Mr. Samuel Townly

Mr. Daniel Trinder

Reverend Mr. C. La Trobe

Clement Tudway, Esq.

Mrs. Twisden

U

Mr. M. Underwood

V

Mr. John Vaughan

Mrs. Vendt

W

The Right Hon. Earl of Warnick

The Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Worcester

The Hon. William Windham, Esq. M.P.

Mr. C.B. Wadstrom

Mr. George Walne

Reverend Mr. Ward

Mr. S. Warren

Mr. J. Waugh

Josiah Wedgwood, Esq.

Reverend Mr. John Wesley

Mr. J. Wheble

Samuel Whitbread, Esq. M.P.

Reverend Thomas Wigzell

Mr. W. Wilson

Reverend Mr. Wills

Mr. Thomas Wimsett

Mr. William Winchester

John Wollaston, Esq.

Mr. Charles Wood

Mr. Joseph Woods

Mr. John Wood

J. Wright, Esq.

Y

Mr. Thomas Young

Mr. Samuel Yockney

VOLUME I

I

The author's account of his country, and their manners and Customs – Administration of justice – Embrenche – Marriage ceremony, and public entertainments – Mode of living – Dress – Manufactures Buildings – Commerce – Agriculture – War and Religion – Superstition of the natives – Funeral ceremonies of the priests or magicians – Curious mode of discovering poison – Some hints concerning the origin of the author's countrymen, with the opinions of different writers on that subject.

I BELIEVE it is difficult for those who publish their own memoirs to escape the imputation of vanity; nor is this the only disadvantage under which they labour: it is also their misfortune, that what is uncommon is rarely, if ever, believed, and what is obvious we are apt to turn from with disgust, and to charge the writer with impertinence. People generally think those memoirs only worthy to be read or remembered which abound in great or striking events, those, in short, which in a high degree excite either admiration or pity: all others they consign to contempt and oblivion. It is therefore, I confess, not a little hazardous in a private and obscure individual, and a stranger too, thus to solicit the indulgent attention of the public; especially when I own I offer here the history of neither a saint, a hero, nor a tyrant. I believe there are few events in my life, which have not happened to many: it is true the incidents of it are numerous; and, did I consider myself an European, I might say my sufferings were great: but when I compare my lot with that of most of my countrymen, I regard myself as a particular favourite of Heaven, and acknowledge the mercies of Providence in every occurrence of my life. If then the following narrative does not appear sufficiently interesting to engage general attention, let my motive be some excuse for its publication. I am not so foolishly vain as to expect from it either immortality or literary reputation. If it affords any satisfaction to my numerous friends, at whose request it has been written, or in the smallest degree promotes the interests of humanity, the ends for which it was undertaken will be fully attained, and every wish of my heart gratified. Let it therefore be remembered, that, in wishing to avoid censure, I do not aspire to praise.

That part of Africa, known by the name of Guinea, to which the trade for slaves is carried on, extends along the coast above 3400 miles, from the Senegal to Angola, and includes a variety of kingdoms. Of these the most considerable is the kingdom of Benen, both as to extent and wealth, the richness and cultivation of the soil, the power of its king, and the number and warlike disposition of the inhabitants. It is situated nearly under the line, and extends along the coast about 170 miles, but runs back into the interior part of Africa to a distance hitherto I believe unexplored by any traveller; and seems only terminated at length by the empire of Abyssinia, near 1500 miles from its beginning. This kingdom is divided into many provinces or districts: in one of the most remote and fertile of which, called Eboe, I was born, in the year 1745, in a charming fruitful vale, named Essaka. The distance of this province from the capital of Benen and the sea coast must be very considerable; for I had never heard of white men or Europeans, nor of the sea: and our subjection to the king of Benen was little more than nominal; for every transaction of the government, as far as my slender observation extended, was conducted by the chiefs or elders of the place. The manners and government of a people who have little commerce with other countries are generally very simple; and the history of what passes in one family or village may serve as a specimen of a nation. My father was one of those elders or chiefs I have spoken of, and was styled Embrenche; a term, as I remember, importing the highest distinction, and signifying in our language a mark of grandeur. This mark is conferred on the person