The Life of Olaudah Equiano, Gustavus Vassa the African (Summarized Edition) E-Book

Olaudah Equiano

0,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Quickie Classics

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

First published in 1789, The Life of Olaudah Equiano, Gustavus Vassa the African blends spiritual autobiography, travel narrative, and abolitionist argument. Equiano traces his Eboe childhood, abduction and the Middle Passage, enslavement in the Americas, naval service, mercantile work, and the purchase of his liberty. In lucid, poised prose, he fuses ethnographic observation with Enlightenment reason and evangelical reflection to indict Atlantic slavery. Born c. 1745 and known in Britain as Gustavus Vassa, Equiano educated himself at sea and in Atlantic ports, embracing Anglican evangelicalism and collaborating with abolitionists like Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson. After buying his freedom in 1766, he ranged from the Caribbean to the Arctic as a sailor and merchant. His encounters with imperial warfare and commerce sharpened his critique; later debates over his birthplace highlight, rather than diminish, his self-fashioned authority. This landmark of Black Atlantic literature remains essential for students of history, religion, and autobiography, and for any reader seeking a clear-eyed primary witness. Read it for its moral clarity, narrative craft, and analytic intelligence, and for the still-urgent case it makes against racialized exploitation. Equiano's narrative reshapes how we think about freedom, citizenship, and the making of a modern global conscience. Quickie Classics summarizes timeless works with precision, preserving the author's voice and keeping the prose clear, fast, and readable—distilled, never diluted. Enriched Edition extras: Introduction · Synopsis · Historical Context · Author Biography · Brief Analysis · 4 Reflection Q&As · Editorial Footnotes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2026

Ähnliche

The Life of Olaudah Equiano, Gustavus Vassa the African (Summarized Edition)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Poised between captivity and self-authorship, this narrative follows an individual who learns to survive a world that treats people as cargo while insisting on the moral and imaginative claims of freedom, moving across oceanic distances, languages, and legal systems to expose how empire, commerce, and faith shape the possibilities of a life, and inviting readers to witness not only the material pressures of the transatlantic slave trade but also the resilient formation of a speaking, reasoning self that gathers experience, tests belief, seeks community, and patiently transforms suffering into testimony aimed at recognition, reform, and the redefinition of what it means to be human.

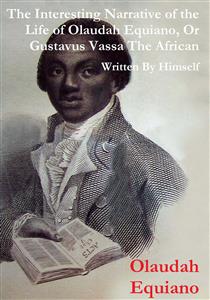

First published in London in 1789 as The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, this work is an autobiography often grouped with eighteenth-century slave narratives and travel writing. Its settings range across the Atlantic world—West African communities, Caribbean plantations, North American ports, and British cities—capturing the commercial and political currents of the age. Appearing amid intense debate over the transatlantic slave trade, the book reached a broad audience and became a touchstone in antislavery circles. Readers encounter a self-authored life that is at once personal history, cultural document, and public intervention.

In broad outline, the narrative begins with childhood in West Africa and a sudden rupture that forces the protagonist into the networks of enslavement and maritime labor. From that threshold, the book proceeds through ships and shorelines, households and decks, markets and churches, always attentive to the textures of work, exchange, and encounter. The voice is lucid, measured, and capacious, balancing curiosity with moral purpose. The style blends vivid travelogue, economic observation, and reflective analysis; the tone is earnest and persuasive without surrendering to despair. The opening movement establishes a world in motion and a speaker determined to interpret it.

One of the work’s central themes is the collision between human dignity and a system that renders people commodities. Equiano’s account shows how markets, law, and violence converge to regulate bodies, families, and movement, and how skill, language, and literacy become tools for survival and argument. The narrative’s observational rigor—its attention to prices, routes, and shipboard routines—anchors its ethical claims in concrete experience. Faith and conscience also matter: the book probes the uses and abuses of religious language while searching for a framework that can hold suffering and hope together. The result is a sustained critique embedded in lived detail.

Identity is negotiated at every turn, and the doubleness of the author’s names—Olaudah Equiano and Gustavus Vassa—signals a life shaped by coercion and choice, memory and reinvention. The narrative tracks how a person navigates forced renaming, cross-cultural contact, and new literacies to assemble a coherent self that can speak to multiple audiences. This process includes learning maritime skills, acquiring languages, and mastering the genres and expectations of British print culture. The book thus offers a study in authorship as agency: a demonstration of how telling one’s story can reclaim history from records designed to erase or control it.

As literature, the narrative is carefully structured, episodic yet cumulative, arranging voyages and scenes so that observation builds into moral argument. As advocacy, it addresses readers directly and trusts evidence to persuade, using concrete incidents to illuminate systemic wrongs. The publication itself participated in public debate in Britain, and the book’s reception helped strengthen arguments for reform. What stands out today is the interplay between craft and purpose: the plain style that treats detail as proof, the rhetorical restraint that heightens credibility, and the insistence that testimony can change what powerful institutions count as knowledge and whose voices count.

For contemporary readers, the book remains vital because it joins witness to analysis, tracing how global trade, war, and law entangle ordinary lives while also modeling ways to think and act ethically within compromised systems. It speaks to ongoing questions about racial hierarchy, migration, debt and labor, and the making of citizenship. It challenges the habits of distance that can dull moral attention and instead invites close observation, comparative thinking, and empathy governed by reason. Entering this narrative is to meet a guide who neither sensationalizes nor minimizes, and who asks us to measure freedom by the lives it sustains.

Synopsis

First published in 1789, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself presents an autobiographical account that moves from childhood memories to transatlantic travels, from enslavement to hard-won liberty, and toward public advocacy. Framed as both personal testimony and moral argument, the book addresses British and transatlantic readers who were debating the slave trade. Equiano positions his life as evidence, assembling scenes, documents, and reflections to expose the commerce of slavery and to articulate a claim to personhood. The narrative’s sequence follows his changing circumstances, highlighting how character, faith, and enterprise interact with law, violence, and opportunity.

Equiano opens by recounting his early years in the African interior, describing the community he calls Eboe and the social structures, rituals, and economic practices that shaped his childhood. He portrays family life, agricultural routines, and initiation customs to argue for the richness and order of African societies. These passages establish a baseline of belonging and instruct the reader in local norms before any European contact enters his story. The emphasis on kinship, honor, and mutual obligation frames the moral stakes of what follows, contrasting the coherence of his home with the disruptions produced by slaving networks.

The narrative then relates his kidnapping as a child and forced movement across unfamiliar territories toward the coast. Through successive sales, separations, and encounters with different languages and customs, he records the disorientation of being treated as property. His account of the Middle Passage dwells on crowding, disease, and fear aboard the slave ship, set against the routines of maritime discipline. Without sensational detail, he shows how the trade’s logistics convert people into cargo. The experience also marks his first sustained contact with European technology and authority, shaping his later understanding of power and commerce.

After arrival in the Americas, Equiano is sold and put to work before being purchased by a British naval officer who renames him Gustavus Vassa. Life at sea introduces him to navigation, naval hierarchy, and warfare-era mobilization, along with intermittent instruction, baptism, and developing literacy. He learns to operate within European institutions while remaining legally unfree, a tension that structures many episodes. Even moments of trust or partial autonomy remain precarious, dependent on owners’ choices. This phase exposes him to an Atlantic world in motion, where military, commercial, and personal interests intersect and where a change in command can alter a life’s course.

Equiano is subsequently sold into the Caribbean commercial sphere, where plantation economies and inter-island trade define daily realities. He works aboard ships, observes transactions, and negotiates within allowances granted to him, learning how credit, prices, and goods circulate. He documents punishments, the pressure of debts, and the constant threat of resale, but also the small spaces in which enslaved people could earn, bargain, and plan. Patient accumulation and careful relationships eventually enable him to secure his legal freedom. The episode underscores both the cruelty of a system that monetizes liberty and the ingenuity required to navigate it under watchful authority.

As a free sailor and trader, Equiano ranges across Atlantic and European ports, encountering shifting laws and status markers that still place him at risk. He details attempted frauds, racial insults, and bureaucratic obstacles that test the meaning of freedom in practice. At the same time, he invests in education, deepens his Christian commitments, and refines his economic skills. Voyages provide vantage points on colonial societies and the reach of slavery into every harbor. The narrative pauses frequently to weigh profit against conscience, measuring the costs of complicity and the responsibilities of witness in a world organized around coerced labor.

Equiano’s experiences lead him into reformist circles in Britain, where petitions, pamphlets, and personal narratives shape public debate on the slave trade. He reports collaborating with activists, addressing audiences, and contributing evidence to campaigns. He also recounts involvement in schemes related to the resettlement of free Black people to West Africa, revealing administrative conflicts and ethical dilemmas that accompany large projects of relief and governance. Throughout, he presents his book as both testimony and livelihood, using subscription publishing and an extensive readership to extend his reach while documenting the practical challenges of advocacy.

Stylistically, the narrative blends ethnography, travel writing, spiritual reflection, and commercial detail. Equiano addresses readers as moral agents and as participants in imperial markets, balancing appeals to sympathy with arguments about policy, law, and national interest. He juxtaposes African and European customs to question cultural hierarchies, and he uses account-keeping and contracts to show how slavery operates through paperwork as much as force. The book’s structure mirrors his life’s transitions, with documents and letters punctuating episodes, and with moments of introspection that consider providence, character formation, and the uses and limits of self-reliance.

The work closes by consolidating its purpose as a carefully assembled case against the trade in human beings and a claim for Black self-authorship. Without relying on revelation or dramatic reversal, it builds cumulative authority from lived experience, documentary support, and measured critique. As autobiography and political intervention, Equiano’s narrative became a touchstone for abolitionists and a foundational text of Black Atlantic literature. Its enduring significance lies in how it links individual story to systemic analysis, inviting readers to reckon with the entanglements of profit, law, faith, and freedom that defined the eighteenth-century Atlantic world.

Historical Context

In the late eighteenth century, the British Atlantic world linked West Africa, the Caribbean, North America, and Europe through war, commerce, and migration. London was a publishing center where travelogues, conversion narratives, and political pamphlets reached an expanding reading public. The transatlantic slave trade underwrote imperial wealth, and British shipping dominated many routes. Intellectual life blended Enlightenment empiricism with evangelical revivalism, shaping debates about morality, commerce, and rights. Olaudah Equiano’s narrative appeared in this milieu in 1789, speaking from within the maritime and imperial systems that defined the era while addressing audiences formed by both scientific curiosity and Christian reform.

In the mid-eighteenth century, the Bight of Biafra became one of the principal embarkation zones for captives forced into the Atlantic slave trade. European traders anchored off coastal entrepôts and river estuaries, purchasing people through local brokers tied to regional conflicts and long-distance commerce. Equiano presents himself as originating from Igbo-speaking society in this region, a detail that situates his perspective within West African cultural life disrupted by Atlantic demand. British, French, and Portuguese vessels carried many from this coast directly to Caribbean plantations and to ports in British North America, making the area central to the era’s coerced migrations.

Transatlantic shipping turned people into commodities through financial instruments, insurance, and maritime law. The Middle Passage subjected captives to confinement, disease, and high mortality, supplying labor to plantation economies in Jamaica, Barbados, Virginia, and beyond. Sugar, tobacco, and other staples financed metropolitan banks and manufacturers, while colonial slave codes enforced racialized bondage. British investors and insurers in the City of London profited from this commerce, and naval protection sustained the routes. These institutions form the structural backdrop against which Equiano’s experiences at sea, in ports, and across colonies unfold, informing his critique of a system that treated human life as cargo.