4,49 €

4,49 €

oder

-100%

Sammeln Sie Punkte in unserem Gutscheinprogramm und kaufen Sie E-Books und Hörbücher mit bis zu 100% Rabatt.

Mehr erfahren.

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Kim Paradowski

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

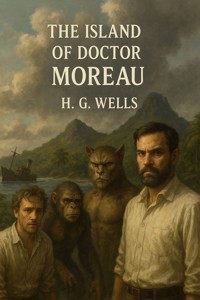

- This is an illustrated edition featuring detailed artwork, a complete summary, an author biography, and a full list of major characters.

This illustrated edition brings Wells’s haunting vision to life with evocative artwork that deepens the atmosphere of tension and wonder. The accompanying summary provides a clear and engaging overview of the story, while the author biography offers insight into Wells’s life, influences, and the scientific concerns that shaped his writing. A helpful character list is also included to guide new readers through the novel’s dramatic cast.

Perfect for classic literature lovers, students, and collectors, this edition presents a timeless science fiction masterpiece in a visually engaging and accessible format. Whether you’re encountering the story for the first time or rediscovering it, this version enhances the reading experience and illuminates one of Wells’s most unforgettable works.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

0,0

Bewertungen werden von Nutzern von Legimi sowie anderen Partner-Webseiten vergeben.

Legimi prüft nicht, ob Rezensionen von Nutzern stammen, die den betreffenden Titel tatsächlich gekauft oder gelesen/gehört haben. Wir entfernen aber gefälschte Rezensionen.

Ähnliche

The Island of Doctor Moreau

By

H. G. Wells

ABOUT WELLS

H. G. Wells was born Herbert George Wells on September 21, 1866, in Bromley, Kent, England. His early life was marked by financial difficulty, and his parents’ modest income left him with limited opportunities. A childhood accident that confined him to bed introduced him to the world of books, sparking a lifelong love of reading. This interest later led him to pursue education with determination despite social and economic obstacles.

In his teenage years, Wells apprenticed in various trades but found little satisfaction in these roles. His ambitions pushed him toward academics, and he eventually earned a scholarship to the Normal School of Science in London. There he studied biology under the famous scientist T. H. Huxley, whose evolutionary teachings heavily influenced Wells’s thinking. This scientific background shaped the themes and speculative ideas that would later define his writing career.

Wells began his literary journey as a journalist and short-story writer before achieving fame as a novelist. His early works, including The Time Machine (1895), The Invisible Man (1897), and The War of the Worlds (1898), established him as a pioneer of modern science fiction. These novels explored advanced technology, evolution, and the potential dangers of scientific progress, often serving as social commentary on Victorian society. His writing combined imagination with scientific insight, which gave his stories a sense of realism and urgency.

Beyond science fiction, Wells wrote extensively on politics, history, and social reform. He advocated for education, global cooperation, and improved living conditions for ordinary people. His nonfiction works and utopian novels reflected his belief that society could progress through reason and scientific understanding.

SUMMARY

The Island of Doctor Moreau follows Edward Prendick, a shipwreck survivor who is rescued and brought to a remote island. At first, Prendick knows little about the place except that its inhabitants seem unusual and the atmosphere tense. He is taken in by Montgomery, a man who assists the island’s master, the enigmatic Dr. Moreau. As Prendick regains strength, he senses that the island hides disturbing secrets, especially when he hears strange cries echoing from the jungle.

Prendick soon discovers that Dr. Moreau is conducting gruesome scientific experiments. Moreau, once driven out of England for his unethical work, uses vivisection to reshape animals into humanlike creatures. These “Beast Folk” walk upright, speak in broken language, and obey a set of strict laws meant to suppress their animal instincts. Prendick is horrified by these beings and even more by the cold, obsessive nature of Moreau, who believes his work is justified in the pursuit of scientific progress.

As time passes, the veneer of control over the Beast Folk begins to erode. Moreau insists that pain and fear are enough to keep them obedient, but the creatures struggle against their nature. Prendick witnesses the fragility of Moreau’s authority as some of the Beast Folk show signs of reverting, their instincts overwhelming the artificial laws imposed on them. The balance on the island becomes increasingly unstable.

The situation collapses when a violent accident leads to the deaths of both Moreau and Montgomery. Without their human overseers, the Beast Folk begin to lose whatever humanity Moreau forced upon them, slipping back into their original animal behaviors. Stranded and alone, Prendick tries to survive among them, but the island becomes increasingly dangerous as the creatures revert and the social order disintegrates.

CHARACTERS LIST

Edward Prendick

The novel’s narrator and protagonist; a shipwreck survivor who ends up on Moreau’s island.

Dr. Moreau

A brilliant but cruel scientist exiled from England; he performs vivisection experiments to create human–animal hybrids.

Montgomery

Moreau’s assistant. He rescued Prendick at sea and is the only other human living on the island.

M'ling

Montgomery’s loyal servant; one of Moreau’s creations, part animal and part human.

The Sayer of the Law

A Beast Folk leader who recites Moreau’s rules (“The Law”) to keep the hybrids in line.

The Leopard-Man

One of the Beast Folk who struggles intensely with his animal instincts. Later killed by Prendick and others.

The Ape-Man

A talkative hybrid who resembles an ape and forms somewhat of a connection with Prendick.

The Hyena-Swine

One of the most violent and dangerous Beast Folk who eventually becomes an antagonist to Prendick.

The Dog-Man

A loyal Beast Man who becomes Prendick’s companion after Moreau’s death.

The Wolf-Men (multiple)

Beast Folk with wolf traits; they appear during hunts and group scenes.

Captain of the Ipecacuanha

The drunken and abusive captain who initially transports Prendick before abandoning him at sea.

The Mate of the Ipecacuanha

The more reasonable second-in-command on the ship; shows some sympathy for Prendick.

INTRODUCTION

I. IN THE DINGEY OF THE “LADY VAIN”

II. THE MAN WHO WAS GOING NOWHERE

III. THE STRANGE FACE

IV. AT THE SCHOONER’S RAIL

V. THE MAN WHO HAD NOWHERE TO GO

VI. THE EVIL-LOOKING BOATMEN

VII. THE LOCKED DOOR

VIII. THE CRYING OF THE PUMA

IX. THE THING IN THE FOREST

X. THE CRYING OF THE MAN

XI. THE HUNTING OF THE MAN

XII. THE SAYERS OF THE LAW

XIII. THE PARLEY

XIV. DOCTOR MOREAU EXPLAINS

XV. CONCERNING THE BEAST FOLK

XVI. HOW THE BEAST FOLK TASTE BLOOD

XVII. A CATASTROPHE

XVIII. THE FINDING OF MOREAU

XIX. MONTGOMERY’S BANK HOLIDAY

XX. ALONE WITH THE BEAST FOLK

XXI. THE REVERSION OF THE BEAST FOLK

XXII. THE MAN ALONE

INTRODUCTION.

ON February the First 1887, the Lady Vain was lost by collision

with a derelict when about the latitude 1’ S. and longitude 107’

W.

On January the Fifth, 1888—that is eleven months and four days after—

my uncle, Edward Prendick, a private gentleman, who certainly went

aboard the Lady Vain at Callao, and who had been considered drowned,

was picked up in latitude 5′ 3″ S. and longitude 101’ W. in a

small open boat of which the name was illegible, but which is

supposed to have belonged to the missing schooner Ipecacuanha.

He gave such a strange account of himself that he was supposed demented.

Subsequently he alleged that his mind was a blank from the moment

of his escape from the Lady Vain. His case was discussed among

psychologists at the time as a curious instance of the lapse

of memory consequent upon physical and mental stress.

The following narrative was found among his papers by the undersigned,

his nephew and heir, but unaccompanied by any definite request

for publication.

The only island known to exist in the region in which my uncle was

picked up is Noble’s Isle, a small volcanic islet and uninhabited.

It was visited in 1891 by H. M. S. Scorpion. A party of sailors

then landed, but found nothing living thereon except certain curious

white moths, some hogs and rabbits, and some rather peculiar rats.

So that this narrative is without confirmation in its most

essential particular. With that understood, there seems no harm

in putting this strange story before the public in accordance,

as I believe, with my uncle’s intentions. There is at least

this much in its behalf: my uncle passed out of human knowledge

about latitude 5’ S. and longitude 105’ E., and reappeared

in the same part of the ocean after a space of eleven months.

In some way he must have lived during the interval. And it seems that

a schooner called the Ipecacuanha with a drunken captain, John Davies,

did start from Africa with a puma and certain other animals aboard

in January, 1887, that the vessel was well known at several ports

in the South Pacific, and that it finally disappeared from those seas

(with a considerable amount of copra aboard), sailing to its unknown

fate from Bayna in December, 1887, a date that tallies entirely with my

uncle’s story.

CHARLES EDWARD PRENDICK.

(The Story written by Edward Prendick.)

I. IN THE DINGEY OF THE “LADY VAIN.”

I DO not propose to add anything to what has already been written

concerning the loss of the “Lady Vain.” As everyone knows,

she collided with a derelict when ten days out from Callao.

The longboat, with seven of the crew, was picked up eighteen days after

by H. M. gunboat “Myrtle,” and the story of their terrible privations

has become quite as well known as the far more horrible “Medusa” case.

But I have to add to the published story of the “Lady Vain”

another, possibly as horrible and far stranger. It has hitherto

been supposed that the four men who were in the dingey perished,

but this is incorrect. I have the best of evidence for this assertion:

I was one of the four men.

But in the first place I must state that there never were four men

in the dingey,—the number was three. Constans, who was “seen

by the captain to jump into the gig,”<1> luckily for us and unluckily

for himself did not reach us. He came down out of the tangle

of ropes under the stays of the smashed bowsprit, some small rope

caught his heel as he let go, and he hung for a moment head downward,

and then fell and struck a block or spar floating in the water.

We pulled towards him, but he never came up.

<1> Daily News, March 17, 1887.

I say lucky for us he did not reach us, and I might almost

say luckily for himself; for we had only a small breaker

of water and some soddened ship’s biscuits with us, so sudden

had been the alarm, so unprepared the ship for any disaster.

We thought the people on the launch would be better provisioned

(though it seems they were not), and we tried to hail them. They could

not have heard us, and the next morning when the drizzle cleared,—

which was not until past midday,—we could see nothing of them. We could

not stand up to look about us, because of the pitching of the boat.

The two other men who had escaped so far with me were a man named Helmar,

a passenger like myself, and a seaman whose name I don’t know,—

a short sturdy man, with a stammer.

We drifted famishing, and, after our water had come to an end,

tormented by an intolerable thirst, for eight days altogether.

After the second day the sea subsided slowly to a glassy calm. It is

quite impossible for the ordinary reader to imagine those eight days.

He has not, luckily for himself, anything in his memory to imagine with.

After the first day we said little to one another, and lay

in our places in the boat and stared at the horizon, or watched,

with eyes that grew larger and more haggard every day, the misery

and weakness gaining upon our companions. The sun became pitiless.

The water ended on the fourth day, and we were already thinking

strange things and saying them with our eyes; but it was, I think,

the sixth before Helmar gave voice to the thing we had all been thinking.

I remember our voices were dry and thin, so that we bent towards

one another and spared our words. I stood out against it with all

my might, was rather for scuttling the boat and perishing together

among the sharks that followed us; but when Helmar said that if his

proposal was accepted we should have drink, the sailor came round

to him.

I would not draw lots however, and in the night the sailor whispered

to Helmar again and again, and I sat in the bows with my clasp-knife

in my hand, though I doubt if I had the stuff in me to fight;

and in the morning I agreed to Helmar’s proposal, and we handed

halfpence to find the odd man. The lot fell upon the sailor;

but he was the strongest of us and would not abide by it, and attacked

Helmar with his hands. They grappled together and almost stood up.

I crawled along the boat to them, intending to help Helmar by grasping

the sailor’s leg; but the sailor stumbled with the swaying of the boat,

and the two fell upon the gunwale and rolled overboard together.

They sank like stones. I remember laughing at that, and wondering

why I laughed. The laugh caught me suddenly like a thing

from without.

I lay across one of the thwarts for I know not how long,

thinking that if I had the strength I would drink sea-water

and madden myself to die quickly. And even as I lay there I saw,

with no more interest than if it had been a picture, a sail come

up towards me over the sky-line. My mind must have been wandering,

and yet I remember all that happened, quite distinctly.

I remember how my head swayed with the seas, and the horizon

with the sail above it danced up and down; but I also remember

as distinctly that I had a persuasion that I was dead, and that I

thought what a jest it was that they should come too late by such

a little to catch me in my body.

For an endless period, as it seemed to me, I lay with my head

on the thwart watching the schooner (she was a little ship,

schooner-rigged fore and aft) come up out of the sea.

She kept tacking to and fro in a widening compass, for she was

sailing dead into the wind. It never entered my head to attempt

to attract attention, and I do not remember anything distinctly after

the sight of her side until I found myself in a little cabin aft.

There’s a dim half-memory of being lifted up to the gangway, and of

a big red countenance covered with freckles and surrounded with red

hair staring at me over the bulwarks. I also had a disconnected

impression of a dark face, with extraordinary eyes, close to mine;

but that I thought was a nightmare, until I met it again.

I fancy I recollect some stuff being poured in between my teeth;

and that is all.

II. THE MAN WHO WAS GOING NOWHERE

THE cabin in which I found myself was small and rather untidy.

A youngish man with flaxen hair, a bristly straw-coloured moustache,

and a dropping nether lip, was sitting and holding my wrist.

For a minute we stared at each other without speaking.

He had watery grey eyes, oddly void of expression.

Then just overhead came a sound like an iron bedstead being

knocked about, and the low angry growling of some large animal.

At the same time the man spoke. He repeated his question,—“How do you

feel now?”

I think I said I felt all right. I could not recollect how I

had got there. He must have seen the question in my face,

for my voice was inaccessible to me.

“You were picked up in a boat, starving. The name on the boat

was the `Lady Vain,’ and there were spots of blood on the gunwale.”

At the same time my eye caught my hand, thin so that it looked

like a dirty skin-purse full of loose bones, and all the business

of the boat came back to me.

“Have some of this,” said he, and gave me a dose of some

scarlet stuff, iced.

It tasted like blood, and made me feel stronger.

“You were in luck,” said he, “to get picked up by a ship with a

medical man aboard.” He spoke with a slobbering articulation,

with the ghost of a lisp.

“What ship is this?” I said slowly, hoarse from my long silence.

“It’s a little trader from Arica and Callao. I never asked

where she came from in the beginning,—out of the land

of born fools, I guess. I’m a passenger myself, from Arica.

The silly ass who owns her,—he’s captain too, named Davies,—

he’s lost his certificate, or something. You know the kind of man,—

calls the thing the `Ipecacuanha,’ of all silly, infernal names;

though when there’s much of a sea without any wind, she certainly

acts according.”

(Then the noise overhead began again, a snarling growl

and the voice of a human being together. Then another voice,

telling some “Heaven-forsaken idiot” to desist.)

“You were nearly dead,” said my interlocutor. “It was a very

near thing, indeed. But I’ve put some stuff into you now.

Notice your arm’s sore? Injections. You’ve been insensible for nearly

thirty hours.”

I thought slowly. (I was distracted now by the yelping of a number

of dogs.) “Am I eligible for solid food?” I asked.

“Thanks to me,” he said. “Even now the mutton is boiling.”

“Yes,” I said with assurance; “I could eat some mutton.”

“But,” said he with a momentary hesitation, “you know I’m dying to hear

of how you came to be alone in that boat. Damn that howling!”

I thought I detected a certain suspicion in his eyes.

He suddenly left the cabin, and I heard him in violent controversy

with some one, who seemed to me to talk gibberish in response to him.

The matter sounded as though it ended in blows, but in that I thought

my ears were mistaken. Then he shouted at the dogs, and returned to

the cabin.

“Well?” said he in the doorway. “You were just beginning to tell me.”

I told him my name, Edward Prendick, and how I had taken to Natural

History as a relief from the dulness of my comfortable independence.

He seemed interested in this. “I’ve done some science myself. I did

my Biology at University College,—getting out the ovary of the earthworm

and the radula of the snail, and all that. Lord! It’s ten years ago.

But go on! go on! tell me about the boat.”

He was evidently satisfied with the frankness of my story,

which I told in concise sentences enough, for I felt horribly weak;

and when it was finished he reverted at once to the topic

of Natural History and his own biological studies. He began to

question me closely about Tottenham Court Road and Gower Street.

“Is Caplatzi still flourishing? What a shop that was!”

He had evidently been a very ordinary medical student, and drifted

incontinently to the topic of the music halls. He told me

some anecdotes.

“Left it all,” he said, “ten years ago. How jolly it all used to be!

But I made a young ass of myself,—played myself out before I was

twenty-one. I daresay it’s all different now. But I must look up

that ass of a cook, and see what he’s done to your mutton.”

The growling overhead was renewed, so suddenly and with so much savage

anger that it startled me. “What’s that?” I called after him,

but the door had closed. He came back again with the boiled mutton,

and I was so excited by the appetising smell of it that I forgot

the noise of the beast that had troubled me.

After a day of alternate sleep and feeding I was so far recovered

as to be able to get from my bunk to the scuttle, and see the green

seas trying to keep pace with us. I judged the schooner was running

before the wind. Montgomery—that was the name of the flaxen-haired man—

came in again as I stood there, and I asked him for some clothes.

He lent me some duck things of his own, for those I had worn in the boat

had been thrown overboard. They were rather loose for me, for he was

large and long in his limbs. He told me casually that the captain

was three-parts drunk in his own cabin. As I assumed the clothes,

I began asking him some questions about the destination of the ship.

He said the ship was bound to Hawaii, but that it had to land

him first.

“Where?” said I.

“It’s an island, where I live. So far as I know, it hasn’t got

a name.”

He stared at me with his nether lip dropping, and looked so wilfully

stupid of a sudden that it came into my head that he desired

to avoid my questions. I had the discretion to ask no more.

III. THE STRANGE FACE.

WE left the cabin and found a man at the companion obstructing

our way. He was standing on the ladder with his back to us,

peering over the combing of the hatchway. He was, I could see,

a misshapen man, short, broad, and clumsy, with a crooked back,

a hairy neck, and a head sunk between his shoulders. He was dressed

in dark-blue serge, and had peculiarly thick, coarse, black hair.

I heard the unseen dogs growl furiously, and forthwith he ducked back,—

coming into contact with the hand I put out to fend him off from myself.

He turned with animal swiftness.

In some indefinable way the black face thus flashed upon me

shocked me profoundly. It was a singularly deformed one.

The facial part projected, forming something dimly suggestive

of a muzzle, and the huge half-open mouth showed as big white teeth

as I had ever seen in a human mouth. His eyes were blood-shot

at the edges, with scarcely a rim of white round the hazel pupils.

There was a curious glow of excitement in his face.

“Confound you!” said Montgomery. “Why the devil don’t you get

out of the way?”

The black-faced man started aside without a word.

I went on up the companion, staring at him instinctively

as I did so. Montgomery stayed at the foot for a moment.

“You have no business here, you know,” he said in a deliberate tone.

“Your place is forward.”

The black-faced man cowered. “They—won’t have me forward.”

He spoke slowly, with a queer, hoarse quality in his voice.

“Won’t have you forward!” said Montgomery, in a menacing voice.

“But I tell you to go!” He was on the brink of saying something further,

then looked up at me suddenly and followed me up the ladder.

I had paused half way through the hatchway, looking back, still astonished

beyond measure at the grotesque ugliness of this black-faced creature.

I had never beheld such a repulsive and extraordinary face before,

and yet—if the contradiction is credible—I experienced at

the same time an odd feeling that in some way I had already

encountered exactly the features and gestures that now amazed me.

Afterwards it occurred to me that probably I had seen him as I

was lifted aboard; and yet that scarcely satisfied my suspicion

of a previous acquaintance. Yet how one could have set eyes on

so singular a face and yet have forgotten the precise occasion,

passed my imagination.

Montgomery’s movement to follow me released my attention, and I

turned and looked about me at the flush deck of the little schooner.

I was already half prepared by the sounds I had heard for what I saw.

Certainly I never beheld a deck so dirty. It was littered with

scraps of carrot, shreds of green stuff, and indescribable filth.

Fastened by chains to the mainmast were a number of grisly staghounds,

who now began leaping and barking at me, and by the mizzen a huge puma was

cramped in a little iron cage far too small even to give it turning room.

Farther under the starboard bulwark were some big hutches containing

a number of rabbits, and a solitary llama was squeezed in a mere

box of a cage forward. The dogs were muzzled by leather straps.

The only human being on deck was a gaunt and silent sailor at

the wheel.

The patched and dirty spankers were tense before the wind,

and up aloft the little ship seemed carrying every sail she had.

The sky was clear, the sun midway down the western sky;

long waves, capped by the breeze with froth, were running with us.