Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

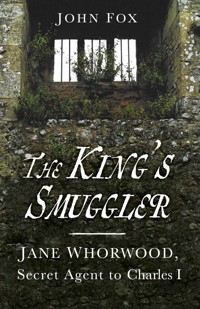

Jane Whorwood(1612–84) was one of Charles I's closest confidantes. The daughter of Scots courtiers at Whitehall and the wife of an Oxfordshire squire, when the court moved to Oxford in 1642, at the start of the Civil War, she helped the Royalist cause by spying for the king and smuggling at least three-quarters of a ton of gold to help pay for his army. When Charles was held captive by the Parliamentarians, from 1646 to 1649, she organised money, correspondence, several escape attempts, astrological advice and a ship to carry him to Holland. The king and she also had a wartime 'brief encounter'. After Charles's execution in 1649, Jane's marriage collapsed in one of the most public and acrimonious separation cases of the seventeenth century. Using crucial evidence, John Fox provides a detailed biography of this extraordinary woman, a forgotten key player in the English Civil War.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 506

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the Author

JOHN FOX wrote the new entry ‘Jane Whorwood’ for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography in 2009, and is a published author on diverse topics from Roman coins to the First World War. The King’s Smuggler was hosted by the Sunday Times Oxford Literary Festival, and is held as the definitive work on the subject.

Also by John Fox

El Proyecto Macnamara: The Maverick Irish Priest and the US–British Race to Seize California, 1844–46 (2014)

Forgotten Divisions: The First World War from Both Sides of No-Man’s-Land (1994)

Roman Coins and How to Collect Them (1983)

Contributor to:

The California Territorial Quarterly (1995–2005)

Oxford Illustrated Encyclopedia, Volume 3, World History to 1800 (1988)

For Glen, Karl, Mark,Daniel and Sarah,with Ellen and Osian,our ‘Secret Islanders’

Cover photograph © Paul Pattison. (See image 15 for full caption.)

First published 2010

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© John Fox, 2010, 2022

The right of John Fox to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7524 6903 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface and Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

Timeline

Genealogy

1. 1612–84: Finding Jane Whorwood

Westminster

2. 1612–19: Jeane Ryder, ‘Bairn’ in a ‘Scottified’ Court

3. 1619–34: James Maxwell, Black Rod and Stepfather

Oxford

4. 1634–42: Four Weddings: Whorwoods, Hamiltons, Cecils and Bowyers

5. 1642–46: ‘Madam Jean Whorewood’, Gold-Smuggler Royal

6. 1646: Bridget Cromwell’s Wedding, Naseby Day, Holton House

Newcastle to the Isle of Wight

7. 1647: ‘Mistress Whorwood, Committee Chairwoman?’

8. November 1647–June 1648: ‘715’ and a Frightened King

9. June–November 1648: ‘Sweet 390 … Your Most Loving 391’

10. November 1648–June 1651: The End of Service

Oxford and London

11. 1651–59: Divorce from Bed and Board

12. 1660–84 ‘Poor Mistress Whorwood’

List of Illustrations

1. Charing Cross, 2009. Charles I’s statue (1633) marks the site of the medieval cross and of the regicide executions in 1660.

2. James Maxwell, Earl of Dirleton (c.1580–1650), Jane Whorwood’s stepfather in old age.

3. Old St Paul’s and London Bridge. As the sun encircles the earth, so the king enlightens the City, Return from Scotland Medal, 1633.

4. Holton House, c.1785, watercolour by Richard Corbould, whereabouts unknown.

5. Holton House site today. A fixed bridge replaces the drawbridge.

6. The filled-in basement of the south-west wing, beyond which a bridge connected the rear courtyard to the park.

7. Diana, Viscountess Cranborne, née Maxwell (1622–75), Jane Whorwood’s half-sister.

8. Oxford, 1644 (Crown coin).

9. Holton St Bartholomew’s Church Register, 15 June 1646.

10. The Holton Cromwell portrait, now Oxford University’s official picture of its chancellor, 1650–58.

11. Carisbrooke Castle courtyard and gatehouse from the bedchamber window of the king’s first lodging.

12. Carisbrooke Castle courtyard and the king’s first lodging, seen through the Gatehouse doorway.

13. Carisbrooke Castle courtyard, from the battlements.

14. Carisbrooke Castle from the approach road.

15. The king’s chamber cell at Carisbrooke Castle.

16. Commonwealth Silver Coins: a 1649 sixpence (measuring 25mm) and two undated halfpennies (measuring 10mm each).

17. St Bartholomew’s church, Holton, where Jane, Brome, three of their four children, Brome’s mistress Kate Allen, and their child ‘cousin Thomas’ were buried.

Preface and Acknowledgements

In 2009, ODNB requested a new ‘Jane Whorwood’ entry to replace one by Sir Charles Firth published in 1884. When I thanked editor Lawrence Goldman for the encouragement, he replied, ‘She is a much more interesting figure than Sir Charles Firth realised or composed for the first DNB.’

In January 2010, The History Press published The King’s Smuggler: Jane Whorwood, Secret Agent to Charles I. A month later, musicians from Wheatley Park School and Pembroke College, Oxford, joined forces to help launch the new book yards from the moated former site of Holton House. All six movements of The Jane Whorwood Suite were heard, however faintly, across old Holton Park.

That March, The Sunday Times hosted the book in its Oxford Literary Festival, held at Christ Church. The college had been King Charles’s former garrison palace, parliament house and lodging. ‘History whisperers’ knew the locale and had encouraged my work. I thank them for their push! Some had even rowed around and cleared Holton moat. Kevin Heritage, long a friend and colleague (and, from 2022, ‘Moat Manager Ret’d’), helped Stephanie Jenkins and Nigel Phillips found the school History Archive. Marian Browne of Holton church, and Julia and Brian Dobson of Holton community, often quizzed me; Caroline Dalton and Kay Hay unearthed minor archive gems.

Nothing is ever too local at the Bodleian Library, where Cromwell’s portrait (by Walker), found in a lumber room at old Holton House in 1801, reminds everyone that he was once Oxford’s ‘Chancellor, Benefactor and Protector’. More and wider research flowed in from Lambeth Palace, Windsor Castle, Guildhall Library, British Library, LSE Library, The National Archives (Kew) and National Archives (Scotland). The Royal Librarian ‘tested’ my wife and me (leniently) on ‘Hellen’s’ 1848 cipher and handwriting.

I owe old thanks to Sarah Poynting (Keele), Malcolm Gaskill (E. Anglia), Martin Maw (OUP) and numismatist friends at the Ashmolean. The late John Prest, Vetelegan and Balliol historian, read my first manuscript as ‘that mythical general reader’ and with typical modesty. Paul Pattison, Senior Historian, English Heritage, has helped and encouraged this new edition of 2022. Nadine Akkerman (Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in 17th Century Britain, OUP, 2018) gave welcome critical coverage to my work and shared being puzzled by the smuggling of gold in soap – one luxury hiding another. Her typical ‘She-intelligencer’ was ‘invisible, mobile, crossed enemy lines, was politically active, drawn into or devising future schemes, and even walked in and out of the King’s prison cell to discuss secrets’. Jane Whorwood’s ‘invisibility’ certainly ‘makes the job of the modern historian particularly hard’ (p. 26).

If ‘invisibility’ sheltered Jane Whorwood from her own generation, it is not surprising that no canvas or paper portrait of her exists. Words did describe her – ‘Tall, Red-haired, Well fashioned, Round-visaged, Pock-holed in face, Well languaged’.

After her cause to liberate King Charles collapsed she earned no title, jewels, pension, portrait or land. Throughout the short English Republic, she had nothing to celebrate save for her having had the courage to follow her Royalist cause. The 2010 edition of this book featured on its cover a Lely portrait of Jane’s half-sister, Diana, Viscountess Cranborne. Pearls from the Maxwell wealth – one result of family success in East India and Scottish African merchant companies – adorn Diana’s hair, neck and clothing. We also considered a finely sketched ‘impression’ of Jane in similar pearls for the 2022 book cover, but the dilemma remained: how do we portray the invisible? Instead we have adopted the king’s last chamber cell at Carisbrooke Castle, now a roofless ruin. It saw his last escape attempt. At midnight on 29 May 1648, he used nitric acid and a hacksaw on a high window bar. Sentries alerted the governor, who opened the chamber-cell door at midnight to explain that he wished ‘to take leave of Your Majesty, for I hear you are going away’. Reputedly the king laughed, from relief. Those waiting for him below the outer wall fled, pursued by musket fire. It was his last escape attempt, and by then Parliament, losing trust in him, had voted by a slim majority to enter talks with him about the future.

Stuart courtiers’ descendants and those of others spoke after 2010 – family echoes, not archive scraps. In 2013, General John Napier III, ex-US Army, revealed family memories of Patrick Napier, King Charles’s barber surgeon. James Ayton corresponded about Sir Robert Aytoun, poet and diplomat close to James Maxwell and stepdaughter Jane Whorwood, née Ryder (James Ayton, The Stuart Experience, Dove, 1996). Sir Robert’s poetry included the earliest known version of ‘Auld Lang Syne’. In 1638, he bequeathed a ‘best Bed’ to Jane, in an era when a guest bedroom with the finest furniture made for a daytime venue for hosts, guests and visitors. More came from Alan Dell, descendant of William, Parliamentarian Army chaplain. Most tangible was a 6in-long ‘shaft and globe’ wine bottle, c.1675–80, with Whorwood crest, from close to the Scots enclave of St Andrew’s Parish, Holborn. Jane found twenty years’ refuge there from her husband’s violence at Holton. The Whorwood crest, a stag’s head with oak branch and acorn in mouth, identified the customer whose bottle was due to be refilled by the vintner.

Oxford astrophysicist Lynas Grey literally shed moonlight for me on the king’s letters of 3–4 May 1648. Ian Felix, old friend and good listener, has shared his expertise in numismatics and bullion over the last forty-five years. Andrew Kinnier introduced us to Cromwell’s Sydney Sussex College and Maxwell’s Inns of Court. The late Martin Roberts, a valued colleague of many years and educator of repute, quietly and generously encouraged my work at Cherwell comprehensive school. He also broadened my hinterland. I owe him much else and am proud to have worked alongside him.

I try to replace ‘Civil War’ with ‘the War’ and ‘Wartime’. Even in the 1640s it was felt that ‘civil’ was no way to describe the brutal reality of polarising communities and families. Sometimes I cite ‘Mistress’ (‘Mrs’ in full) as stronger than today’s muttered abbreviation. (‘Master’ is dead beyond reviving.) John Taylor, known as the ‘Water Poet’, whose biographer calls him a ‘genial companion’, lightened up Wartime Oxford, romanticising the Thame at Wheatley Bridge, enjoying beer and oysters on the Medway and kissing the king’s hands at Carisbrooke. Wartime was not always sombre. Taylor made people laugh, as only a pub-landlord-poet could.

In Chapter 6 I have recreated the Bridget Cromwell–Henry Ireton field wedding in Holton House. It marked the first anniversary of Naseby, allowing Naseby generals to ‘leap and smile’ before Oxford surrendered. Naseby had led up to it. The nine-line wedding certificate is a little-known cameo of national issues – religious, military and governmental. Jane and her mother-in-law were both royalists, but Ursula Whorwood wrote Jane out of her will just months after the wedding. Jane’s Brabanter mother had been ‘Lavander’ to Queen Anne, who was also rumoured to be Catholic. Ursula’s immediate Brome and Whorwood families had remained recusants into the 1630s, a century-old conservative backcloth which finally came to mean loyalty to the Crown. Few in that Wartime were strangers to religious conflict or watching their backs.

***

My simple, heartfelt love and thanks to Glen, my wife and best friend for half a century, for her love, support, patience, sharing and understanding. We’re given love, we don’t earn it.

John Fox,Wheatley, Oxford,April 2022

Abbreviations

APC

Acts of the Privy Council

CCAM

Calendar of the Committee for the Advance of Money

CCC

Calendar of the Committee for Compounding (and Sequestration)

CSP

Calendar of State Papers

HCJ

House of Commons Journal

HER

English Historical Review

HLJ

House of Lords Journal

HMC

Historical Manuscripts Commission (Reports)

LSE

London School of Economics

Ms(s)

Manuscript(s)

NAS

National Archives of Scotland

ODNB

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (‘New’ DNB)

PROB

Probate

RPCS

Records of the Privy Council of Scotland

SP

State Papers

TNA

The National Archives (formerly PRO, Public Record Office)

Timeline

1603

James VI of Scotland succeeds Elizabeth I as James I of England

1612

Jeane Ryder born to Scots court officials, William Ryder, Principal Harbinger of Horse, and Elizabeth de Boussyne, Queen Anne’s laundress, at Westminster

1615

Brome Whorwood born at Holton Park, Oxfordshire

1617

James I and VI visits Scotland; William Ryder dies

1619

Jeane’s mother remarries to James Maxwell, Black Rod. Queen Anne dies

1625

Charles I succeeds James I; Maxwell’s influence grows at court as Garter Usher and Groom to the King’s Bedchamber

1625

Parliament removes to Oxford to avoid plague

1628

Buckingham, favourite of Charles I and James I, assassinated

1629

Parliament dissolves itself; King Charles rules alone until 1640

1634

Brome Whorwood of Sandwell Park, Staffordshire, marries Jeane Ryder, who becomes Jane Whorwood

1636

The court and Archbishop Laud visit Oxford

1639–41

Charles I defeated in two Scottish or ‘Bishops’ wars

1640

Short Parliament (1640); Long Parliament (1640–48); ‘Rump’ (1648–53; 1658–60)

1642

Charles declares war against Parliament, August; Edgehill battle, October

1642

(Approx.) Jane to Holton Park, which was owned by Dame Ursula Whorwood until death, 1653

1642–4

Jane smuggles gold and intelligence into Oxford, Charles’s war capital

1644

Scots Covenanting Army invades in support of Parliament

1645

Parliament abolishes Anglican Church and re-models army; Naseby battle, June

1646

Charles flees Oxford; Scots take him to Newcastle; Bridget Cromwell marries at Holton; Oxford surrenders; end of ‘first civil war’

1647

Jane follows the king, Northampton to Surrey, February–October

1647–8

Agreement at Newcastle on Scots war expenses; Charles handed into English custody; travels via Holdenby to Hampton Court; army subdues London; Charles flees to Isle of Wight after army threats

1648

King on Wight, November 1647 – November 1648; four failed escape attempts, naval mutiny, county uprisings; Scots invasion by the Hamiltons defeated at Preston; Royalists surrender Colchester; end of ‘second civil war’; Parliament negotiates with Charles, August – November; army arrest him

1649

Charles I executed; monarchy and House of Lords abolished; Commonwealth (Republic) declared; army take war into Ireland and Scotland

1651

Prince Charles and Hamilton invade England from Scotland (‘third civil war’); defeated at Worcester, September; Jane Whorwood returns to Holton, but the marriage is violent and volatile

1657

Jane leaves home permanently; son Brome junior drowns in the Solent

1658

Cromwell dies and is succeeded by son Richard, briefly and reluctantly

1659

Jane obtains judicial separation and alimony from Brome

1660

Charles II invited to return in a ‘Restoration’ of monarchy

1661

Brome Whorwood MP for Oxford City, over three Parliaments, 1661–81

1663

May. Brome MP seeks Commons vote to annul Jane’s alimony as from usurpation period. Jane to Bar of Commons to plead MPs’ Wife’s Privilege; Commons annuls ‘Wife’s Privilege’. Then prorogued.

1664

February, Jane petitions Charles II, is awarded her case, but Brome pays no alimony

1665

June, Charles asks Chancellor Hyde to enforce; Brome defies

1666

August, Charles rules in her favour, with Chancellor Hyde to enforce. Brome ignores again

1668

6 May, Jane at Bar of Commons with her files from the 1659 Chancery Court judgement which had awarded her alimony. Summer recess stops debate

1669

King hears testimony in person again and supports it

1672

Brome demands Jane return to Holton, which would annul all alimony. By 1673 she has received just 42 per cent of alimony owed her since 1659

1681

Jane pleads to the king in person again that she has received no alimony for nine months

1684

Brome Whorwood dies, April; Jane Whorwood dies, September. Buried at Holton

1688–9

Flight of James II; William of Orange and Mary (née Stuart) offered Crown

1

1612–84:Finding Jane Whorwood

A tall, well-fashioned and well-languaged gentlewoman, with a round visage and with pock holes in her face.

Anthony Wood to Derby House Committee, 1648

She was red haired, as her son Brome was, and was the most loyal person to King Charles I in his miseries of any woman in England.

Anthony Wood, Oxford, 1672

No known portrait exists of Jane Whorwood, but they remembered her height and figure, her fine speech and the flame-hair. Pockmarks spoiled a girl’s marriage prospects, but they made her actions, not her complexion, her measure. Diana Maxwell, Jane’s half-sister, sat for Lely, the court painter, and was celebrated for her looks, but they only remembered her greed. Jane’s marriage broke up violently, publicly, and after three of her four children had died. No Whorwood staircase or Great Parlour would have hung her portrait, and given the tempo of her life she would hardly have sat still long enough to be painted. John Cleveland of the Oxford garrison wrote To Prince Rupert, a tribute to ideal beauty, male or female,

Such was the painter’s brief for Venus’ face,

Item, an eye from Jane, a lip from Grace.

All others named in his poem are real and Jane Whorwood was Cleveland’s Wartime contemporary in Oxford. A Titian-haired Scot with green or hazel eyes, a painter’s convention, turned heads in a small city; Anthony Wood and Elias Ashmole also remembered her from there years later. Red hair was an obstacle in life, but it was memorable, like the pocks.

The failure of her cause helps explain Jane Whorwood’s obscurity. Jane Lane succeeded in helping Charles Stuart II escape after his defeat at Worcester in 1651; she sat for Lely, had a pension from the king and a valuable jewel from Parliament. Flora McDonald was painted onto the popular mind (and shortbread tins) for assisting another Charles Stuart, self-styled ‘III’, to flee his failed uprising in 1746. Jane Whorwood, despite several attempts in 1648–9, failed to free her Charles Stuart I. There was nothing to celebrate, except her courage in the trying. The occupational secrecy of a clandestine agent hid that, along with the rest of her service record. Conspirators were often hidden, even from each other. ‘What other private agents the king had at London, I do not well know,’ wrote John Barwick, clerical spy and secret correspondent with King Charles I: he knew fellow-conspirators only ‘as it were through a lattice and enveloped in a mist’.

The Stuarts were always fugitives, Scottish, but aliens at home as much as in England, although they had ruled unruly Scotland for 200 years. South of the border they were married to queens from Denmark, France and Portugal, and ruled England for only eighty-five years (eleven of those from exile), little more than Jane Whorwood’s lifespan. King James’s mother, Mary of Scots, fled in and out of her own country; as a child James was carried in flight; Charles I fled London for Oxford, and Oxford for Newark, from where in defeat he was conveyed like a caged bird to Newcastle, then back to Hampton Court, from where supporters led him to the Isle of Wight and much nearer to France. After a failed uprising, botched escape attempts and futile talks, the army put him on trial.

Charles II, the fugitive king-in-waiting, returned in 1660, but not to the land he left. Parliament, Nonconformists, generals, the Irish and the Scots had discovered their strength. His brother, James II, fled the country with his successor a babe in arms, but Dutch William and his Stuart wife stepped to the throne by invitation and broke the direct Stuart line. Pretenders pretended, but the battle of Culloden in 1746 terminated the Stuart threat (if not the pretence) to the two kingdoms, now united. The last pretender, Cardinal ‘Henry IX’, styled himself humbly in Italy, King of England by the Grace of God, but not by the Will of the People. After the battle of the Nile, Nelson exchanged gifts with Henry, George III healed scars and finally moved on with a pension to the cardinal and Canova’s monument to the pretenders in St Peter’s, Rome.

The English War and ensuing Republic prompt many ‘what if?’ questions. What if the king had won, or abdicated? What if Richard Cromwell had been stronger? If Ireton had lived longer, would the English Republic have been ‘the Consulate’ not the Protectorate? Similarly, what if Jane Whorwood had freed Charles I? In the summer of 1648, as the king’s escape committee grew weary of repeated failure and Jane emerged from a naval mutiny and county uprising on the Medway, the Marquess of Hertford wrote from London to Jane’s brother-in-law, William Hamilton, Earl of Lanark, in Edinburgh: ‘Had the rest done their parts as carefully as Wharwood [sic], the king would have been at large.’1

Her mother’s two marriages and her own wrapped her in family surnames like a fog. She was Ryder from her German-born Scots father. Her mother, born de Boussy in Antwerp, changed Ryder to Maxwell on remarriage. Jane married into the Staffordshire and Oxfordshire Whorwoods, spelled variously Whorewood (pronounced ‘Horrud’ in the nineteenth century), Horwood (as pronounced now), and Harwood. Jane was London-Scottish-Brabanter, and Scottish tradition recognised the maiden name after marriage. Her Ryder and Maxwell sisters took on more surnames – Hamilton, Cecil, Bowyer and Delmahoy. To complicate further, her mother and stepfather were ennobled in 1646 as Earl and countess of Dirleton, on the Forth. While Jane was the quintessential Royalist and an Oxfordshire squire’s wife, her red hair and given names ‘Jeane’ and ‘Ginne’ were those of someone more than nominally Scottish. Her Charing Cross home was in ‘Little Edinburgh’, but Holborn St Andrews Parish, her last refuge in life, had been a key London–Scots settlement since Queen Elizabeth’s death in 1603. Her younger sisters married aristocratic dynasts in both countries, and Jane named her daughters after them.

Jane left no will or last words, although some of her letters survive. She died in genteel poverty, possibly mentally damaged. No Whorwood ever mentioned her in a will; her three sisters predeceased her and ignored her, as did most of those who once conspired with her in the king’s cause. Her mother, however, and members of the Hyde-Clarendon family, remembered her generously. The evidence for her early life at Whitehall is unusually focused because of the court roles of her parents, her stepfather, and her sisters’ husbands. The site of her childhood home at the top western side of Whitehall is occupied (appropriately for ‘Little Edinburgh’) by the old Drummond Bank, now Royal Bank of Scotland. The nearby equestrian statue of Charles I marks the site of Charing Cross, Jane’s waking landmark in life. Her first married home, Sandwell Park, Staffordshire, is now a golf course; her second at Holton Park, Oxfordshire, is occupied by a university campus and a comprehensive school. Her final decades were spent in Soho and Holborn. All her homes have gone, but at least the atmospheric moated site of Holton House survives as a hidden Oxfordshire gem.

Other buildings she knew still stand, if slightly modified: Carisbrooke Castle, Passenham Manor, Oxford’s colleges, Hampton Court Palace and the Banqueting House, Whitehall, on which Rubens was working when she left home for married life in Oxford. Only a fraction remains of Holdenby House, ‘pulled down [in 1649] two years after [the king’s stay], among other royal houses, whereby the splendour of the kingdom was eclipsed’.2 No record suggests Jane visited Scotland, but her father died after organising the royal visit there in 1617, and her stepfather hosted travelling kings at his Innerwick mansion near the Forth. His castle at Dirleton, decrenellated after its 1,400-man garrison surrendered, is a tourist draw, but the Maxwell Aisle in Dirleton kirk lacks the ambitious marble monument Jane’s mother planned for his tomb. Lambert and Monck took the castle with a token mortar salvo after Dunbar in 1650. The chamber where Maxwell died at Holyrood Palace disappeared in the rebuilding by Charles II, but the successor to his coal-fired lighthouse on the island of May in the Firth of Forth still guides ships and can be seen from Edinburgh and Dirleton.

Family life suffered more in the War than bereavement, destruction and confiscation. Insecurity reshaped morality, making for odd bedfellows and intense working relationships. Psychological and marital casualties surfaced afterwards. Whorwood, Milton and Gardiner marriages in the same small area of Oxfordshire were all casualties of the War. Cromwell, Milton and Oglander families were split in their loyalties. Of the Hammonds, Uncle Hammond was the king’s chaplain, nephew Hammond his jailer, and another uncle his judge. The Royalist Whorwoods entertained the puritan wedding of Bridget Cromwell and Henry Ireton, Cromwells and Whorwoods both blood cousins to the iconic John Hampden. The Committee of Both Houses (it exhausted several names) at Derby House which brokered intelligence on Jane’s activities throughout 1648, included her brother-in-law Lord Cranborne. Another brother-in-law, the second Duke of Hamilton and the king’s cousin, to whom Jane was close, died at Worcester after invading England in 1651. When did you last see your father? is a romantic cliché, but it reminds of the separation and insecurity of parents, siblings and children in civil war, which made contemporaries yearn for peace, or at least neutrality. When did you last see your husband? or much more aptly, When did you last see your children? could have been put to Jane Whorwood when she came out of imprisonment in 1651. Childcare is fundamental and Jane’s mother-in-law, Ursula Whorwood, gave legacies to her grandchildren, which jar with the silence she accorded Jane Whorwood, their mother.

Extraordinary public actions often command an unrecorded personal fee. Towards the end of her life ‘poor Mistress Whorwood’, as the bishop of London called her, was an embarrassment, bowed, if not quite broken, and poor. Her husband, MP for Oxford for twenty years and a threat to Charles II, hated her publicly. Jane in turn apologised to the king for his Whig disloyalty. By the end of her life the adventures of her younger years were irrelevant, forty years old, in their day a Wartime secret necessarily kept from co-conspirators and Parliamentarians, yet as forgettable as yesterday’s news. This seventeenth-century secret agent survived England’s civil war physically unscathed, only to be seriously injured afterwards by her manic husband. Failure, divorce and a Whig husband dulled her halo and prevented a legend.

Most of Jane’s close collaborators predeceased her. Life and death rolled on. Rewards to others for service to the dynasty were generous, but thinly spread. Either she did not qualify for, or more likely she did not request, a reward. She was also a woman back in conventional peacetime, the roles and freedom reversed which the War had afforded her. Around her, old courtiers fell out, ‘all at daggers drawn’ as Pepys described them, in haste to reinvent and justify their contribution to the lost royal cause. None blew Jane’s trumpet on her behalf, even former close colleagues. John Ashburnham died still fighting Clarendon’s accusation that he had connived with Cromwell to trap the king on Wight. Henry Firebrace highlighted his liaising of intelligence and escapes for the king but, like Ashburnham, never mentioned Jane Whorwood (though he kept her letters). Silius Titus (‘I have ten times ventured my life in His majesty’s service when his affairs were desperate’) was promoted, rewarded financially and entered Parliament. Thomas Herbert admitted Jane’s role, then took pains to deny it before he died. Sir Purbeck Temple told the wildest tales, with Jane in the background and himself prominently heroic. Outside the restored Prayer Book, Charles I quickly became history as Restoration took over. Jane drew a veil over her activities. In the summer of 1684, just before she died, leading figures at court, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, began to quiz Sir William Dugdale about exactly who had been involved in those daring attempts to liberate the old king.

Dugdale, a chronicler, had tapped Firebrace and Herbert, Jane’s fellow conspirators, for their memories, in order to document the attempts. The letters Firebrace and others preserved, all from 1648, are a small fraction of hundreds of secret messages, written, oral and hand-signalled, from the period.3 No letters survive from Jane directly to the king out of nearly twenty she is known to have written to him in the last six months of 1648. Two have been saved in Charles’s hand to Jane, from almost three dozen he is known to have written to her. Seven can still be read from her to Henry Firebrace, page of the bedchamber and coordinator of intelligence to the king between London and Wight, but they exchanged many more. A single letter, now in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, from Jane (as ‘Hellen’) to William Hopkins of Newport for the king’s eyes also, and two letters in the National Archives of Scotland, from her to her brother-in-law William Hamilton, Earl of Lanark, signed as ‘409’, are all unquestionably in Jane’s handwriting.

That any letters survive at all from the conspirators and the prisoner-king is remarkable, given the danger of writing and receiving them, their regular interception by Parliament, and their routine burning by recipients. The shredder had not been invented, but the Oxford garrison burned almost all its records before surrendering and Secretary Nicholas even ordered King Charles on Wight: ‘For God’s sake, burn them!’ It is all the more remarkable that the two intimate letters from the king to Jane of July 1648 (we cannot judge whether they were the most intimate) should have been preserved at all, when more than fifty others between them were not. Somehow, either they passed from her (or her daughter’s) possession to Firebrace and others, or they may have been left behind at Carisbrooke and cleared by friends like Firebrace after the king’s arrest in Newport in November 1648. They would have made welcome black propaganda for Parliament, more explosive than the letters between king and queen captured after Naseby. Someone also risked treasuring them in the dangerous Republican years up to 1660. Their re-deciphering in 2006 was still able to spark prurient press interest in the martyr-king’s private life.4

Tantalisingly, the 95 per cent of letters now lost between the king and Jane included an intriguing ‘careful postscript’ from Charles, and a ‘wise long discourse’ and a ‘long memorial’ from Jane. The surviving notes themselves (quality cartridge paper endures) are often minute, 4cm by 15cm folded into sixteen, small enough to be concealed in a shoe, the finger of a glove, or in the crack in a wainscot panel. Others to other couriers were hidden under the edge of a chamber carpet, or passed in the act of taking the king’s hand to kiss. They are usually written in cipher, a common convention among letter writers to hide confidences. Jane’s signet and stamp seals on the back of her letters range from simple crest to the marital impaling of Whorwood and Ryder. They may have been useful curios in a writing box, or decoration: Dorothy Osborne carried hers on a chatelaine belt; Queen Henrietta Maria hung her signet at her wrist.

Three of Jane’s autograph signatures survive, in the 1647 papers of the Committee for the Advance of Money at Haberdashers Hall, and in Chancery papers from her judicial separation. She signed enciphered notes variously as ‘N’, ‘390’, ‘409’ and ‘715’, and unciphered or part-ciphered notes as ‘JW’ or with the nom de plume ‘Hellen’.

She was literate and fluent, ‘well-languaged’, and certainly well-connected. The Scottish Hamiltons were addressed by Charles I as ‘cousins’, the Cecils had been the English kingmakers, although Jane’s brother-in-law was strictly a Parliamentarian. Her stepfather was Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod to the Lords, the king’s herald in Parliament and house-jailer to grandees arrested by Parliament. As Usher also to the Order of the Garter, he organised the dazzling liturgy of chivalry around the king. His titles formalised his real use to the Crown as fixer and financier. Sir Robert Maxwell, Jane’s uncle, was Serjeant-at-Arms to the Commons; her stepfather’s cousin, John Maxwell, was Bishop of Ross, Laud’s religious provocateur in Scotland. Two of her in-laws, Bowyer and Cecil, were Long Parliament members, as was her cousin, Sir Christopher Lewknor.

Jane’s web of cousins, in-laws and contacts was wide and can be traced through wills, court cases, church registers, state papers and Heralds’ visitations. Titles honorific to modern ears were power and influence in 1640, the Garter Star being the ultimate elevation. Garter ceremonial enhanced the surviving quasi-sacrament of coronation, whereby God ‘ordained’ the monarch; Order members, like Jane’s brother-in-law Hamilton, had to wear the embroidered Star at all times, proclaiming the king’s (and God’s) favour and virtual presence. Jane’s stepfather derived further public authority from his service to the Order. Family ties between ruling gentry often help make sense of an action or a relationship, as the aristocracy and gentry of the seventeenth century numbered about 100,000 atop a population pyramid of perhaps 5 million. Family was important beyond today’s understanding of its claims. ‘Kinship’ and ‘kinsman’ included distant cousins and even people of the same name; ‘family’ included gentlefolk attendants, servants and tenants. Ann Manwood, Captain Maxwell and Jane Sharpe, all deployed by the Countess of Dirleton to monitor Jane’s imploding marriage at Holton, were ‘family’. If Mrs Cromwell and Lady Whorwood really did sit down after the Naseby wedding at Holton with the genealogy charts, which we know were in the house, they would have found extensive family in common.

The letters by which Jane is best known are not the only or even the main sources for her life. She shared the discomforts of garrison life at Oxford for four years with the king and court, with Sir Thomas Bendish (interrupted by a twenty-month imprisonment in the Tower), Sir Lewis Dyve, the Marquess of Hertford, Anthony Wood, Elias Ashmole, John Ashburnham and his gentleman John Browne, not to mention the fugitive merchants of the Levant and East India companies, commercial partners of her stepfather before they fled to Oxford. They invoked her name afterwards, as did William Lilly, the national astrologer who was himself a Parliamentarian agent. In 1651, when she was fined for ‘applying herself to [corrupting]’ the chairman of a parliamentary committee, the dossier recorded her name with six different spellings.5 Astonishingly for 1647, a Royalist mocked the same committee by asking whether Jane Whorwood was its real ‘Chairwoman’. In 1659 she obtained a judicial separation from her husband on the grounds of his life-threatening violence. Her well-marshalled witnesses crushed any riposte his legal expertise might concoct. She had fled from home twice. Vivid, virtually scripted accounts of the violence, insults, and her husband’s passion for a maidservant, are preserved in Lambeth Palace.6 Repeatedly, after judicial separation in 1659, her husband withheld alimony; repeatedly she fought him for it, at the Bar of the Commons demanding Parliamentary privilege, appearing before Charles II three times and rejecting his judgement, distraining her husband’s property by forced entry, and finally attempting to annul his will in the last months of her life. She literally went down fighting. Jane Whorwood played out her life on two levels, defending firstly her king, and then herself, and in the service of both no tactic or weapon was beneath her.

Piecing together the story of Jane Whorwood for the first time is like attempting to restore a shattered vase from pieces, fragments and slivers; some well known, others newly discovered, many missing, yet the sum restoration never recreates the tension or vibrancy of the intact original.7 It merely indicates it. Her smuggling of nearly 800 kilos of gold to the king at Oxford has only now come to light; her missing years still tantalise; the received caricature of a passing royal mistress distorts perspective. However misplaced, her loyalty was genuine, courageous and acknowledged by those who knew her, including the king, who expected loyalists ‘to forsake themselves’ for him. She was ruthless in his cause, smuggling, embezzling and bribing; she was warm and reckless, in and out of season. Sadly, for the rest of her life she paid for it. When, in 1648, she described one dangerous urgent journey as ‘like a Romance [novella]’, she was war-weary, but had not yet had the full invoice for her adventures.

The front line wedding of Cromwell’s daughter to General Ireton at the Whorwood home, Holton House, deserves closer investigation, even though the royalist Whorwoods hosting and attending were silent witnesses. It was Cromwell’s first attempt, however confused, at a political marriage alliance. In less than six years, his radical ‘junior consul’ took the English Revolution to the brink, and Cromwell with him. The wedding was among the first solemnised by the new Parliamentarian ritual, but with two ministers, a Royalist rector registering and a New Modelled Army chaplain officiating. It also marked the first anniversary of the crucial battle of Naseby. Surprisingly, Victorian genre painters failed to notice it. The Commonwealth took marriage out of church jurisdiction two centuries ahead of today’s civil registration.

Given that Jane was Charles I’s intelligence agent, financial conduit and escapologist, and allowing their ‘brief encounter’ in the summer of 1648, she has still had to be romanticised to make up for the lack of portrait. This freeze-frames her in 1648, ignoring her saddened old age. She becomes the disappearing rustle of a long skirt, a riding habit or a sea cloak; she is the Royalist in dashing, colourful company, like the boy in blue facing darkly dressed interrogators. She is never old, riding post-haste between Wight and London to warn the king, or waiting for him on board ship in the Medway mutiny. Jane was one of a small band of women ahead, at least of their recorded time, in performing what Clarendon called ‘intrigues which at that time could be best managed and carried on by ladies’. She shared the spirit of the chatelaines of both sides defending their houses or sustaining the old religion in the absence of husbands, women who brought out what a servant described as Cromwell’s ‘feminine compassion towards distress’. Her War role, however, was not as poet, diarist or letter writer observing the War, nor as wife, mistress or colourful shadow to a warring male; she was directly involved, often sola, at risk, and answerable directly to the king’s person. When this maverick returned home her marriage became her second ‘war’.

Jane has been a useful joker, replacing lost cards. She is depicted at Holdenby in the king’s early captivity, dropping a message behind an arras as she was body-searched, ‘most likely Jane Whorwood’. She was, in fact, elsewhere at the time.8 Her breaking through the king’s escort to hug him on his way to execution so powerfully evokes Veronica comforting Christ that it has been relayed by several modern historians. Flame-hair and dark cloak against purifying white frost on the royal park is a vivid palette, but as unverifiable (and as moving) as the unscriptural Veronica herself. The women at Christ’s tomb are also invoked, in ‘Jane Whorwell [sic]’, the mysterious lady who asked Sir Purbeck Temple to find Charles I’s body. A study of seventeenth-century bank records recently attributed to ‘Lady Jane Whorwood’ a current account which clearly belonged to Lady Ursula Whorwood, her estranged mother-in-law.

Even a Jane Whorwood hoax has been perpetrated, Piltdown-style, to compromise historians.9The Tendring Witchcraft Revelations was a purported manuscript source which an MI5 cipher clerk confected in 1976. ‘Richard Deacon’ (Donald McCormick), wove together Jane Whorwood’s activities in 1647–8 with those of William Lilly, the national astrologer. Lilly left notes of his clients in which Jane Whorwood does feature, but Deacon alleged that the two travelled together to Essex in 1647 to meet Matthew Hopkins the witchfinder. Hopkins, claimed Deacon, had known Whorwood since 1642 when he told her of his Huguenot family, the ‘Hopequins’. The source also revealed that Hopkins was a double-agent, driven by money whether bartering intelligence or hunting witches, therefore ready to help Jane Whorwood and her Royalist friends.

The MI5 cryptographer was understandably attracted by enciphered correspondence between the king and his circle, including Jane, but cipher was a device long used by correspondents. Jane’s red hair may have suggested the witch link to Deacon, but in 1648, more relevantly, it marked out a Scot. The real Jane Whorwood story has been shipwrecked on fictions and distortions, not to mention the narrows of moral rectitude: Cordell Firebrace in 1932 actually censored the original sources of Jane’s and the king’s more earthy asides. Jane was a secret agent in royal service, ruthless and unscrupulous, spying, smuggling gold in bulk to the king’s capital at Oxford and managing the king’s attempted escapes. She brought him passing physical warmth and evidently ‘applied herself’ elsewhere for the cause, but it was not the sum of her story. Her fight for personal survival at home after the War proved to be as gripping as her Wartime adventure, and consistent with it.

In 1978 an American academic produced a by-product novel, à la Cartland. Jane Whorwood would have called it a romance and enjoyed it. Sweete Jane came from the opening words of a letter to her from the king in 1648. Like the Deacon hoax, the novel was to help fill the wall where a portrait might have hung. Distance-research from New York caused solecisms about the grandeur of Holton ‘town’, its ‘castle’, and the geography of Jane’s England. Jane’s emotional geography was even more graphic, as lover variously to the ambassador to Constantinople, to the lord mayor of London, to the governor of the Tower, and to King Charles himself. Had it all been true, Jane’s husband might have been forgiven his fleeing abroad for the duration of the War and for distancing himself from her after it. However, the scholar novelist added an appendix listing allusions to Jane which other professionals may not have noticed.10

Nineteenth-century folk tradition around Jane’s former home at Holton still remembers the family which gave the village in one lifetime its ration of excitement for the millennium. One tale runs of a boy killed by a wicked governess: in reality Jane’s son did drown at sea in 1657, aged twenty-two, the year she fled from her husband and his mistress who had the title ‘governness’ at Holton House. Another tale told of Brome, Jane’s husband, being summoned to London ‘dead or alive’ by angry royal command, and how he killed himself, but left an empty coffin to taunt the king – a great oak in Holton Park is still called the Breame Oak, and has at times been distorted into Brome Oak to mark this supposed suicide. In reality Brome Whorwood died of a stroke in 1684 in London, four days before he was due to appear before Judge ‘Bloody’ Jeffreys for treasonous talk. Jeffreys demanded testimony on oath that Brome really was dead. Such traditions are rooted in the known local support for Jane against her violent husband before she fled Holton.11

Cromwell’s name is strongly associated with Holton Park because of his daughter’s marriage there. The Holton Cromwell portrait is now Oxford University’s first official portrait of its former Chancellor. The si-dit Holton Cromwell Cup, a Deckelbecker made in Augsburg, said (but only in Victorian times) to have been Cromwell’s gift to the house after the wedding, bears later hallmarks; a cherry tree and a green velvet saddle shared the same tradition. The four years of King Charles’s Oxford ‘head garrison’ have been curiously neglected by historians and this biography only sketches them. Bastioned Oxford and its outer perimeter, which included Holton, lies at the heart of the Civil War narrative and of much of Jane Whorwood’s activity. Oxford’s fall, even if never quite the sack of Troy or the burning of Atlanta, was deeply symbolic.12

Holton House, Jane’s married home, was levelled two centuries ago, ‘because of ghosts’ said local lore. Fragments remain, including an ancient black mulberry which still fruits: they planted such trees – deep-rooted and productive – to mark important weddings, and Jane did produce a male heir for the Whorwoods. Holton, a medieval pile, was pretentiously remodelled in 1600, and let, neglected, to tenants by 1785 when a direct turnpike road made Oxford more accessible. Local homes still sport panelling and fire surrounds from its demolition sale in 1804. The new owner of Holton Park in 1801, ironically the descendant of Colonel John Biscoe, a regicide, built his ‘statement’ house near the moated site with the proceeds from his West Indies plantations. When Thomas Carlyle visited the park in 1847, after the Rector of Holton told him of Bridget Cromwell’s wedding there, he recorded its evocative atmosphere.13 Victorian renovators obliterated Jane and Brome Whorwood’s graves, and that of Brome’s mistress, in Holton’s tiny chancel, together with any stones which marked them.

The War period is fertile with drama, one of the most harvested fields in English history, and the fate of Charles I still fascinates. Finding Jane Whorwood breaks new soil. Her story was largely lost with her burial in 1684 and the death of her last child in 1701; Diana, her daughter, was the final recipient of any stories her mother may have recounted. This review of the evidence, old and new, shows that Jane was no ‘royal hanger on’ as one modern history described her: she masterminded the king’s two escape bids, and pressed for a third; she organised the main gold flow to his war chest at Oxford; she was the hub of his intelligence network in 1648. Others stole her credit in 1660 when she was too broken to speak up for herself. The feisty lady whom King Charles I called ‘Sweete Jane Whorwood’, and whom her husband called ‘whore, bitch and jade’, is, as Henry Firebrace’s descendant suggested with classic understatement in 1932, ‘a lady worthy of extended notice’.14

Notes

1. ‘H’ to Hamilton, 27 June 1648, Hamilton Papers, Camden Society, NS, 27, 1880, 224. Clearly an aristocrat was writing to his equal. Hertford’s house at Netley was the forward base, near Wight, for conspirators in 1648. Jane and others travelled between Wight and London, often via Netley; John Ashburnham was at Netley, banned from the island, and messages were routed through there; Hertford who had also been in the Oxford garrison, knew Jane and her circle: see Chapter 9, note 20.

2. British Library, Harleian Ms 4704, f. 34, Memoirs of Sir Thomas Herbert.

3. The correspondence frequently refers to Jane Whorwood, but as one among many conspirators. It is summarised in Chapter 8, note 1, and integrated into the narrative of Chapters 8–10. In 1932 Cordell Firebrace published Honest Harry, about his ancestor Henry Firebrace’s royal service. It is well argued, reproduces most of the letters in print, but it is dated: he was proud of his ancestor, he censored the king’s earthier phrases and sometimes transcribed inaccurately.

4. The Times, 20 January 2007, reported that Dr Sarah Poynting of Keele University, while re-decyphering the king’s letters to Jane, had discovered the ancient word ‘swyving’. (‘F--king,’ Dr Poynting explained, ‘is the only modern word which can convey it without being coy.’) The Times commented: ‘the re-decoding of this old love letter makes the Martyr king more like his son the Merry Monarch. Insiders at Court knew about Charles’s mistress, but that was before the Freedom of Information Act.’ The Guardian, 17 January 2007, carried the headline: ‘Historian exposes secret sex life of Charles I.’ Dr Poynting’s research itself appeared more soberly as ‘Deciphering the King: Charles I’s Letters to Jane Whorwood’, The Seventeenth Century, 21, 1 (2006), 128–40.

5. TNA SP 19, 162: 92–8, 103.

6. Lambeth Palace Archives: Whorwood vs Whorwood, Case 9938, 1672, including papers from the Chancery case 1658–9, and from the appeal hearing 1672–3.

7. Victoria County History, Oxfordshire, V, 172, accords Jane Whorwood seven lines. John Fox, ‘Jane Whorwood’, ODNB, 2009. In July 1646 Charles wrote to the queen, ‘failings in friendship animate me to be firm to all those who will not forsake themselves, of which there were many in Oxford’, Charles I in 1646, Camden Series, 1856, OS 63, 99.

8. Pauline Gregg, King Charles I (1981), 412. Jane was in London consulting Lilly the astrologer and corrupting a parliamentary committee when the suspects were remanded at Northampton; ibid., 443. Antonia Fraser, The Weaker Vessel (1984), 227; Alison Plowden, Women All On Fire (1984/2004 ed.), 181. Royalists found ready parallels with the first Good Friday, but no Scots Veronica. The intervention in St James’s Park may be a later (? Victorian) device to gloss over a more cynical Parliamentarian newspaper story, see Chapter 10. Geoffrey Robertson, The Tyrannicide Brief (2005), 201 and n. 3, for ‘Whorwell’; Linda Levy Peck, Consuming Splendour (2005), 257, names Countess Dirleton as an Abbott client, unaware that she was Jane’s mother, while casting Jane’s mother-in-law, Lady Ursula Whorwood, as Jane herself.

9. Richard Deacon, Matthew Hopkins, Witchfinder General (1976), 196. Deacon (real name Donald McCormick) died in 1998. He wrote on MI5, Jack the Ripper, microwave cookery and enciphered erotica. He claimed The Tendring Witchcraft Revelations, Ms, 1725 was compiled 1645–50 by one C.S. Perryman. His ‘citations’ have not been used in this book. Matthew Gaskill in Witchfinders (2005), 283, 342, called it a ‘clever hoax … an elaborate fantasy’ and described it to this author as ‘strange and rather disappointing, invented to add an element of espionage and intrigue to the story … the language is extremely odd. No historian has ever seen it.’

10. Virginia White Fitz, Sweete Jane, Mistress of a Martyr King (1988), 325–8 (Historical Notes). The author, who died in 2005, also published Glorious Conspirator: the Secret Life of John Locke (1990). She suggested that Cleveland’s poem referred to Jane Whorwood’s green eyes, fit for a red-haired Venus with Grace Bellaysis’s shapely shoulders. After the king’s execution, Parliament sold ten Venus paintings from the royal apartments; the Hamilton collection had just as many.

11. Cecil Earle Tyndale-Biscoe, Tyndale-Biscoe of Kashmir (1951), 18–19; Robert Stafford-Biscoe, Tales From Jimmy, Memories of an Oxfordshire Village (1963); Oxfordshire County Council Archive, Holton Parish Box, Par 135/17/JI/2 1859.

12. Frederick John Varley, The Siege of Oxford (1932); Frederick John Varley, Supplement to the Siege of Oxford (1935); Margaret Toynbee and Peter Young, Strangers in Oxford, 1642–46 (1973); Rosemary and Tony Kelly, A City at War: Oxford 1642–46 (1987); Nicholas Tyacke, ed., History of Oxford University, Vol. 4, Seventeenth Century (1997), 687–731; Ian Roy and Dietrich Reinhart, Chapter 4, Civil Wars.

13. After the second edition of Oliver Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches (1846), Thomas Carlyle was informed by the Rector of Holton of the Cromwell wedding, Carlyle Collected Letters, Vol. 21, 77–8, 79, 21 and 24 October 1846. He visited Holton and included it in the third edition of Letters and Speeches, 1849, 200: ‘Lady Whorwood … rather in the royalist direction. Her strong moated house, very useful to Fairfax in those weeks, still stands conspicuous in that region, though now under new figure and ownership; drawbridge become fixed, deep ditch now dry, moated island changed into a flower garden; rebuilt in 1807.’

14. Cordell Firebrace, Honest Harry (1932), 50.

2

1612–19:Jeane Ryder, ‘Bairn’ in a ‘Scottified’ Court1

They beg our goods, our lands and our lives,

They whip our Nobles and lie with our Wives,

They pinch our gentry and send for our Benchers

They stab our Sergeants and Pistol our Fencers

Leave off, proud Scots, thus to undo us,

Lest we make you as poor as when you came to us.

John Chamberlain enclosed to Dudley Carleton, June 1612

Just north of Charing village green and its Eleanor Cross, where The Strand curved southwards to become King Street and Whitehall, stood the Royal Mews. It had once been the Royal Falconry, called a ‘mew’ from the moult (mue, Old French) of a bird of prey. Single-storey stables covered the modern site of Trafalgar Square and the National Gallery. A Gate of the Lions allowed entry to the complex, and its stone frontage curved round up a street named after the spurs made there for fighting cocks. Tudors and Stuarts spent hours in the saddle interweaving politics with the hunt and archaic mounted exercises, ritual chivalry to some and ‘amourous foolery’ to others. The royal horses gave Jeane Ryder’s father his living as one of several overseers or surveyors of The Mews. By 1612, when Jeane was christened a stone-throw away in St Martin’s, the falcons had long gone. The extensive Mews was an ageing but essential transport pool for the growing palace complex at Whitehall. It stabled about 130 horses (from an estimated fifteen breeds) for Crown and court officers’ use, in an establishment divided into Great, Lower Green and Upper Back Mews. It was also a coach and wagon depot.

Falcons had needed less room than horses and the swelling court around Westminster put a premium on ‘parking’, ‘garaging’ and ‘servicing’ space for mounts and vehicles. As many as sixty horses at The Mews were for the king’s exclusive use, and the hay barns, forges, exercise circuits, not to mention the tack, coach and riding school buildings of this great establishment, were essential to maintain them. They were washed and watered at a large pool at the centre of The Mews. Every royal servant had his livery, and in the stables alone, under the master of horse, clerk to the stables and seven surveyors, were lesser surveyors of the races and the hunt, a marshal of the farriers, a bitmaker, a packman, grooms, littermen, waggoners, saddlers, falconers and bow bearers. Prince Henry, heir to James I, had an equestrian complex of his own complete with surveyor’s lodgings built within The Mews after 1605. His public persona was closely identified with horsemanship. When the king moved to other palaces or lodges – Oatlands, Nonsuch, Hampton Court – much of the transport pool moved with him.

Royal bird droppings also took up less space than royal horse manure. A waking experience for the Ryder baby’s nostrils was the smell of The Mews dunghill on Cockspur Street. Its smell blended readily with that of the overburdened drains in a parish where new settlers, mainly Scots, vyed for accommodation close to the new Whitehall palace and the old St James’s. Between 1612 and 1631, Jeane’s first twenty years, the number of households paying the poor rate in St Martin’s parish increased by 250 per cent, the bulk of it on the parish Landside towards St James’s Park, away from the Thames. Revenue rose by 212 per cent and payments to the needy by 222 per cent. Living space expanded as timbered houses extended skywards or out into gardens, even in The Mews compound itself. West of the manure heap lay the Haymarket, which supplied the lofts and barns of The Mews, and ultimately the heap itself.2

The Stuart court had descended on London from Edinburgh nine years before Jeane’s birth. (There, too, a haymarket stood close by the royal stables under Castle Rock.) A courier had hastened north with Queen Elizabeth’s Boleyn ring for James VI of Scotland, a dying monarch’s treasured possession to signal an undisputed succession. James I was proclaimed on the Tiltyard Green at Whitehall in 1603, exactly a century after a Tudor-Stuart marriage which had been intended to unite the two dynasties. Four decades later his son would be executed across the road at the new Banqueting House. Inevitably many English saw the Scots as invading, grasping barbarians, led by mere ‘stewards’ who had transformed a title into a dynastic name. They sprang, it was muttered, from a soil too poor to produce anything more useful than Scotsmen. James ‘VI and I’ never united the two kingdoms – the English Parliament resisted that – but he, his son and his two grandsons did rule them in tandem, one wearer of two crowns in separate courts, ruling through two distant Parliaments and two established churches whose bishops and presbyteries were mutually anathema. Kingdoms so disparate, yoked on such terms, were bound to war with each other.

Scotland provided land tracts from which retainers could assume titles and revenue. England provided a refuge from feuding clans and a moneybag from which to sweeten the loyal. Some aristocrats like the Hamiltons had titles from both kingdoms, but too few of them to bridge the ethnic divide in the way James I had hoped. In the end, the Stuarts lost touch so badly with their roots, that when, in 1644, a Scots army invaded to assist Parliament against him, Charles I eventually turned to them for safety, deluded that they were the lesser of two evils. They ‘sold’ him back to England, ‘too much of a Scot for England, and too much of an Englishman for the Scots’.

At first the new King James from ‘North Britain’ gave office to his own at Westminster and Whitehall, then sensing local grievances attempted some fairer distribution. In 1603 the entire bedchamber staff of sixteen lords, gentlemen, grooms and pages, were Scots, the close ‘cabinet’ of influence around the king; but by 1622 half were English. At least, only half of the Privy Chamber staff of forty-eight were Scots appointments from the start and remained so. This ‘narrowing of counsel’ gave James some security after living in constant fear of assassination; it kept him in qualified touch with Scotland, but it also fuelled racial prejudice in London. Guy Fawkes warned that the two races were irreconcilable: ‘Even were there one religion in England, nevertheless it will not be possible to reconcile these two races, as they are, for very long.’ The venality, sexual laxity and extravagance of the new Scots court, claimed Sir Walter Raleigh, ‘shine like rotten wood’, and repeated scandal among royal favourites shaped that wood. An extravagant Danish queen added to the sense of an alien monarchy and her appetite for ‘playing the child again’ did not help. King James accused Parliament of turning financial issues into attacks on the Scots, while Lord Wentworth accused the Scots of ‘drawing out of the cistern as fast as we could fill it’. James even coined an optimistically named Unite gold piece, yet his own country’s coinage was suspect for its ‘black metal’ (copper) farthings and its formerly debased silver.3

When racial tension was high, the Scots found refuge from insults and violence in the ‘royal’ area round Charing Cross, The Mews, Whitehall Palace and the Scotland Yards. Scots ghetto succeeded Huguenot such, and Little Edinburgh flourished as had Petty France. The neighbourhood was home to better-placed Scots courtiers and close to the palaces, offering symbolic security to the more vulnerable. London prejudices were often revealed only later when the Stuarts could no longer retaliate, and when truth and myth could no longer be disentangled. Scotland, they sneered, was ‘a dunghill, not a kingdom’, Edinburgh a ‘parish not a city’; the ‘swarms who came after [James] sucked him of vast sums’; ‘to be married to a Scots woman is to be married to a carcass in a stinking ditch’; ‘their Sabbath is to preach in the morning and persecute in the afternoon’, although ‘the organ will find mercy because there is affinity between it and the bagpipes’; ‘a tree in Scotland is a show, like a horse in Venice’. Personal hygiene was a soft target, alien toilet routines leaving the Scots and their breath ‘stinking and lousy’. Wars against the Scots were fuelled by such racism and Scotsmen could not win against the inconsistency of prejudice. James I was hated because of his mother’s open Catholicism and his Danish wife’s secret such, but he was also blamed for his country’s Presbyterianism which rejected bishops and ritual as papist relics. Speech is a key indicator of ethnic origin: Shakespeare, it is argued, refrained from aping the Lowland Scots dialect in Macbeth