9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

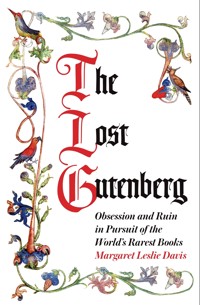

'An entertaining and insightful human story of obsession about books.' Daily Telegraph 'A lively tale of historical innovation, the thrill of the bibliophile's hunt, greed and betrayal.' New York Times The never-before-told story of one extremely rare copy of the Gutenberg Bible, and its impact on the lives of the fanatical few who were lucky enough to own it. For rare book collectors, an original copy of the Gutenberg Bible - there are only forty-six in existence - is the undisputed gem of any collection. The Lost Gutenberg recounts five centuries in the life of one particular copy of the Bible from its very creation by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz, Germany, to its ultimate resting place, in a steel vault under the protection of the Japanese government. Margaret Leslie Davis draws readers into this incredible saga, inviting them into the colourful lives of each of its fanatic collectors along the way. Exploring books as objects of desire across centuries, Davis will leave readers not only with a broader understanding of the culture of rare book collectors, but with a deeper awareness of the importance of books in our world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Published by arrangement with TarcherPerigree, an imprint ofPenguin Random House LLC.

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Margaret Leslie Davis, 2019

The moral right of Margaret Leslie Davis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-763-5

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-764-2

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-765-9

Photos on pp. x, 86, 97, 98, 100, 132, 134, 136, 137 reproduced with the permission of the Archivist of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, on behalf of the copyright holder, The Roman Catholic Archbishop of Los Angeles, a corporation sole.

Photos on pp. 8, 164 courtesy Thomas A. Cahill.

Photos on pp. 15, 24, 33, 39, 43, 51, 58, 59, 71, 86, 108, 140, 142, 157, 158, 168, 179, 181, 183, 186, 208, 215, 227, 236, 238 courtesy Rita S. Faulders.

Photos on pp. 22 and 62 courtesy National Portrait Gallery, London.

Photo on p. 188 courtesy Richard N. Schwab and Thomas A. Cahill.

Photos on p. 246 courtesy Keio University.

Book design by Tiffany Estreicher

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Catherine Chabot Davis

CONTENTS

Part I: The Imperial Century

CHAPTER 1: Million-Dollar Bookshelf

CHAPTER 2: Treasure Neglected

CHAPTER 3: The Bibliophile

CHAPTER 4: The Patriot

Part II: The American Century

CHAPTER 5: The Mighty Woman Book Hunter

CHAPTER 6: The Lost Gutenberg

CHAPTER 7: The Countess and Her Gutenberg

CHAPTER 8: The Nuclear Bibliophiles

Part III: The Asian Century

CHAPTER 9: The Unexpected Betrayal

CHAPTER 10: The Virtual Gutenberg

EPILOGUE: Final Bows

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Estelle Doheny soon after her marriage to oil tycoon Edward Doheny, circa 1900. She was the unseen telephone operator connecting his calls to oil investors and Doheny claimed he was entranced by her voice. They married after a short courtship.

PART I

THE IMPERIAL CENTURY

The Gutenberg Bible is a masterpiece of world culture. Only forty-eight or forty-nine copies of this landmark work survive, and of those, only one has been owned by a woman collector. This is the true story of that book, the copy designated as Number 45, printed by Johann Gutenberg sometime before August 15, 1456.

CHAPTER ONE

Million-Dollar Bookshelf

AWOODEN BOX CONTAINING one of the most valuable books in the world arrives in Los Angeles on October 14, 1950, with little more fanfare—or security—than a Sears catalog. Code-named “the commode,” it was flown from London via regular parcel post, and while it is being delivered locally by Tice and Lynch, a high-end customs broker and shipping company, its agents have no idea what they are carrying and take no special precautions.

The widow of one of the wealthiest men in America, Estelle Betzold Doheny, is among a handful of women who collect rare books, and she has amassed one of the most spectacular libraries in the West. Acquisition of the Gutenberg Bible, universally acknowledged as the most important of all printed books, will push her into the ranks of the greatest book collectors of the era. Its arrival is the culmination of a forty-year hunt, and she treasures the moment as much as the treasure.

Estelle’s pursuit of a Gutenberg began in 1911, when she was a wasp-waisted, dark-haired beauty, half of a firebrand couple reshaping the American West with a fortune built from oil. Now seventy-five, she is a soft, matronly figure with waves of gray hair. The auspicious occasion brings a flash of youth to her face, and she is all smiles. But she resists the impulse to rip into the box, leaving it untouched overnight so she can open it with appropriate ceremony the next day.

Estelle has invited one of her confidants, Robert Oliver Schad, the curator of rare books at the Henry E. Huntington Library, to see her purchase, and at noon he arrives with his wife, Frances, and their eighteen-year-old son, Jasper. Estelle’s secretary, Lucille Miller, escorts the family through the mansion’s Great Hall to the library, and with a sweep of her hand invites the group to sit at the oblong wood table in the center. The Book Room, as Estelle affectionately calls it, is finished in rich redwood and had been her husband’s billiard parlor. Its walls had once featured paintings related to Edward Doheny’s petroleum empire, murals commissioned by the onetime prospector who drilled some of the biggest gushers in the history of oil. Today the room is lined with custom-built shelves for Estelle’s beloved books—her own personal empire, worth as much as Edward’s oil.

Her collection began almost as a lark, sparked by popular lists of books that everyone should own, but now contains nearly ten thousand exceedingly rare volumes available only to the fabulously wealthy and culturally ambitious—gilded illuminated manuscripts glowing with saints and mythical creatures; medieval encyclopedias; and the earliest examples of Western printing, 135 incunabula—books printed before the year 1501. Such seminal works of Western culture as Cicero’s De officiis and Saint Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologica rub shoulders with a sumptuous 1477 copy of The Canterbury Tales. This is the million-dollar company the Gutenberg Bible will keep on its shelf.

The two-by-three-foot crate waits at the center of the table, spotlighted by a bronze-and-glass billiard lamp. When Estelle enters the room, accompanied by her companion and nurse, Rose Kelly, the group stands silent. Lucille takes out a pair of scissors and passes it around. Estelle, dressed for the occasion in a pale blue printed silk dress, a gem-studded comb at her right temple, wants everyone to take part, so each person makes a cut in the knotted cord that winds the package.

It’s an emotional occasion for Lucille, too, a slim, long-limbed woman with center-parted, brown hair that curls up around her cheeks. Never without a pencil tucked behind her ear, she has a subdued beauty that’s easy to miss, a pale, symmetrical face hidden behind her glasses. Lucille has been Estelle’s steady partner in the quest for the Gutenberg, party to every promise, hope, and near miss for nearly twenty years. She almost allows herself to smile as she pulls away the box’s coverings and lifts the lid, but then she sees the shabby mess inside. “I could hardly believe my eyes,” she said later. “It just looked like a bundle of old tattered, torn papers. It was the most carelessly wrapped thing I ever saw.”1 The precious book has been enclosed without padding, wrapped in thin cardboard and then in dark corrugated paper tied with a heavy cord. Lucille mentally chastises the customs officials in New York who had opened the parcel for inspection and then shoved it back in the box “any old way, and tied a string or two here or there and along it came.”2

It will be a miracle if the book is not damaged.

But as she lifts it out of the last of the wrappings, the Bible appears to be fine. For an expert like Robert Schad, there is no mistaking the original fifteenth-century binding of age-darkened brown calfskin stretched over heavy wood boards. The copy now in Estelle Doheny’s possession is the first issue of the first edition of the first book printed with movable metal type, in near-pristine condition, its pages fresh and clean. The lozenge and floweret patterns stamped into the leather cover are still sharp and firm to the touch. Five raised metal bosses protect the covers, one ornament in the center and one set in an inch from each of the four corners. Two broken leather-edge clasps are the only reminders that this book, which has presented the Living Word for nearly five centuries, has been opened and closed often enough to wear down the heavy straps.3

Lucille moves close to her employer, standing on her left and tucking her arm under the spine of the heavy book so that Mrs. Doheny can more easily examine it. Estelle reaches out to touch the fine old leather and slowly lifts the cover and opens the enormous volume. With her gold-framed glasses perched on the edge of her nose, she glides her right hand softly over the edges of the book’s rippling leaves, taking special care not to touch the print. As she turns the crackling pages one by one, she is overcome with quiet joy. Her pursuit of this object of Western invention had begun long ago, during happier days, before her husband was embroiled in scandal. She feels the smoothness of the heavy rag paper under her fingers and strains to focus her gaze on the black Gothic letters, but the Latin text is lost in a cloudy blur and she can’t make out the printed lines. A hemorrhage in one eye and glaucoma in the other have left Estelle almost completely blind at the age of seventy-five.

Still, she knows well what she possesses, and just to be in its presence would be stirring to anyone who understands its significance. The European advancement of printing with movable metal type transformed every aspect of human civilization, and Johann Gutenberg’s execution of the work set a standard that few would match.

As Estelle runs her hands over the book, Schad, a poised man of medium build who’s dressed today in a black suit and tie with a crisp white shirt, points out a few of the qualities that make it unique. Every Gutenberg Bible is somewhat different from every other because while Gutenberg’s workshop printed the pages of each massive volume, the printers left it to the purchaser to have them bound and decorated. Guided by the owner’s taste and budget, a whole team of artisans might step in to customize the book—illuminators would be hired to paint the highly pictorial ornamental letters, and specialists known as rubricators added chapter titles and headings separate from the text.

The first owner of this Bible had not scrimped on ornamentation. The volume is filled with elaborate, richly colored illuminations and enlarged capital letters. In the upper left corner of the first page, a large capital letter F is painted in bright green and gold with ornaments of green leafy vines and tiny, bell-shaped flowers that trace the outer margin. The intricate foliage sweeps down the page and across the bottom, where in the far right corner the artist added a white-bellied blue bird with a bright yellow beak.

Such imagery stands in delicate contrast to the enduring richness of Gutenberg’s type. Jet-black and lustrous, the ink shimmers as if the pages were just recently printed, a quality that was long one of the great mysteries of Gutenberg’s art, a hallmark of the Bibles he printed in Mainz, Germany, before August 15, 1456.

A striking green F and delicately drawn foliage distinguish the first page of the Doheny Gutenberg Bible, printed in Mainz, Germany, sometime before August 15, 1456.

Most scholars believe that Gutenberg produced about 180 copies, and among these, most likely 150 were printed on paper and 30 on animal skin known as vellum. The price of the book when it left the printer’s workshop was believed to be about thirty florins, equivalent to a clerk’s wages for three years. The vellum versions were priced higher, since they were more labor-intensive and expensive to produce—a single copy required the skin of 170 calves.4

Estelle’s copy is one of the forty-five known to exist in 1950. They’re in various conditions, scattered around the world in private libraries and museums: twelve in America, eleven in Germany, nine in Great Britain, four in France, two in Italy, two in Spain, and one each in Austria, Denmark, Poland, Portugal, and Switzerland.5 Fewer than half have all their original pages, a precondition of being designated “perfect.”

Hers is perhaps the most beautiful of the surviving paper copies. Despite its age, this volume lacks no pages and has no serious damage. Designated as Number 45 in a definitive list compiled by Hungarian book authority Ilona Hubay, this Bible has clearly received special care through the centuries, or at least supremely benign neglect.

Gutenberg’s printed pages were usually bound in two volumes, and nearly half of the known copies are considered “incomplete” because the second volume has been lost. That is the case with Number 45, which contains the Old Testament from Genesis through the Psalms. But it is one of the few to retain its original binding, created in Mainz contemporaneously with its printing. The calfskin cover is decorated in a distinctive pattern of impressions. A lattice motif of small diamonds, known by bookmen as a “lozenge diaper,” surrounds six different stamps: an eagle, a trefoil, a fleur-de-lis, and a seven-pointed star. Those details, and the cover as a whole, are in exceptional condition.

Lucille steps aside so that Schad can gently steady the fifteen-pound volume for Estelle. Of all the bookmen who have come and gone during her decades of zealous acquisitions, none have meant more to her than Robert O. Schad, a trusted adviser in her quest, who for the past twenty years has hand-selected the items purchased to strengthen the magnificent “collection of collections” at the Huntington Library.6 Like Estelle, he is completely self-taught, educated through decades of direct contact with the world’s most important books and the famous dealers who trade them. He has always treated her with respect, and always welcomed her questions, no matter how unsophisticated.

Schad signals his son to pick up the Kodak Duaflex twin-lens camera they’ve brought. Jasper rapidly snaps a half-dozen photographs, covering the bulb with a white handkerchief to protect Mrs. Doheny’s sensitive eyes. In one frame, Estelle holds the Bible, gazing down at its pages. As far as Schad knows, this is only the second time a Gutenberg Bible and its owner have been photographed together.

The day has become “boiling hot,”7 and the party retires to the mansion’s Pompeian Room. Beneath a twenty-four-foot-wide Favrile glass dome ceiling attributed to Louis Comfort Tiffany, the group fetes the Gutenberg Bible’s arrival with a luncheon whose menu Lucille saves for the ages: jellied consommé madrilene with crackers and relishes; fried chicken with hominy and hot biscuits; mixed-green salad and a platter of fresh peaches, pears, and persimmons; and a dessert of cream puffs and cookies, with tea served in glasses chilled with an abundance of ice.

According to Lucille’s daybook, the luncheon ends promptly at 2:30 p.m., when she returns to the Book Room to put the Bible back in its shipping box, preserving the tattered wrapping. As she tucks it away, she notices a stiff white card that reads simply: “Customs Officer: Please handle with GREAT CARE and repack in same manner. Thank you.” Below the handwritten note is printed, “With the COMPLIMENTS OF MAGGS BROS. LTD.”

“I am keeping the book,” Estelle hurriedly writes Ernest Maggs, one of London’s revered book dealers, early the following morning. She dispatches a check for twenty-five thousand pounds sterling, the equivalent then of $70,093.8

It is a check that she is delighted to sign. Thanks to a strong US dollar and the recent devaluation of the British pound sterling, she has managed to secure one of Western civilization’s great artifacts at a bargain price. With payment tendered, Estelle Betzold Doheny becomes the first and only woman to purchase a Gutenberg Bible as a private collector.9 Her deep need to own this holy book not only reflects her faith as a devout Catholic but also reveals her shrewd mind for the bottom line.

She tells Lucille she has never felt richer or more content. The book is a panacea for the deep personal losses she has faced, and, she believes, it is a gift from God. It not only lifts her heart, it changes her very image of herself.

AT 8:15 THE next morning, Lucille pulls into the circular driveway of the Doheny mansion in her black Ford Model A. Her first job is to catalog the newest addition to the library, as she’s done since the summer of 1931, when she answered an ad in the newspaper for a temporary typist and signed on, not knowing “a rare book from a pulp novel.”10 Slipping an unruled, white, three-by-five-inch card into her charcoal-gray Royal Aristocrat manual typewriter, she begins: “BIBLIA LATINA [Mainz: Johann Gutenberg, before 15 August, 1456].” In the right-hand corner, she adds the book’s acquisition number, 6979, and underlines it. Then she fills in details of its format and binding, using information sent from Ernest Maggs:

On paper; Gothic type; 324 I. [through the Book of Psalms]; 15 ⅞ in. x 11 ½ in.; double columns of 40–41–42 lines; contemporary stamped calf over wooden boards rebacked, 5 metal bosses on each cover, remains of clasps

She wants to make sure that the news about the purchase doesn’t leak. She’s nervous about keeping the book on the premises, certain that it is “only a matter of time before the secret got out,” and reporters and lookie-loos will be on the front lawn demanding to take pictures.11 Still haunted by the spectacle of the Teapot Dome scandal, when there was no escape from paparazzi and the lurking press, she and Estelle do all they can to avoid bringing attention to the Doheny residence at 8 Chester Place. No one outside the household is told about the book, including the guards posted at the entrance of the gated residential compound in the West Adams neighborhood of Los Angeles.

Lucille is hypervigilant. Each night before she drives home, she checks and double-checks to be sure that Number 45 is safely locked inside the vault that’s hidden behind the thick velvet drapery in the Book Room. She obsesses about making sure the lock is really locked, and more than once she walks back to the Book Room to check it again. “It was up to me to keep the Bible in the book library safe,” Miller said later. “I’ve never been so scared in my life.”12

She is used to handling incunabula, but taking responsibility for a book this significant rattles her. Over the next few days, she calls a handful of experts, saying obliquely that she is seeking advice on how best to preserve a fragile, folio-size, leather-bound book printed on paper from the fifteenth century. The name Gutenberg is never mentioned.

Cautions abound. The book, she is told, must be kept in darkness most of the day because exposure to light could cause ink and pigments to fade, and anytime it is open for display, light levels must be measured and controlled. Inside the vault, it must be securely positioned on a shelf to avoid any accidental damage by bumping. She’s advised to keep the vault as cool as possible, and to watch the relative humidity—if it’s too high, mold could grow; too low and the pages could become desiccated and brittle. Fluctuating levels would be a horror, causing the book to expand and contract, which might lead paper to cockle, ink to flake, and covers to warp.

Ideally, she’ll keep the book between 55 and 68 degrees Fahrenheit, with 35 percent to 60 percent relative humidity. But that’s a fantasy. Los Angeles is in the midst of a mid-October heat wave, and the Doheny mansion isn’t air-conditioned. They’d unpacked the Bible on the hottest day 1950 had seen, and even opening every window of the three-story, 24,000-square-foot residence hadn’t been enough to keep the mid-morning indoor temperature from reaching one hundred sweltering degrees. Somehow, though, the Bible must be kept bone-dry, cool, and stable. Lucille’s great fear, which leaves her “positively terrified,”13 is that the book will develop what she calls “rabbit back,” a badly warped spine caused by a drastic change in the elements.

As the experts talk on, the perils seem endless: insects, including a category known as booklice, or Liposcelis divinatorius,14 and bookworms, which apparently love incunabula’s ancient rag paper.15 Dust, dirt, smoke, or soot, which could absorb and hold moisture, can accelerate deterioration through acid hydrolysis (the chemical decomposition of paper). And there’s no consensus on how much the book can safely be handled. Some advisers suggest turning the pages as little as possible to avoid any damage to the spine, while others insist that paging through it at regular intervals will allow it to “breathe.”

Lucille’s head spins. “It was like having a new baby,”16 she recalled, saying that she was gobsmacked by the weight of the responsibility. She is somewhat relieved when Robert Schad laughs and tries to talk her down, telling her not to fret. He says that almost any librarian can attest that incunabula were built to last in a way that modern books are not. Books printed on the acidic wood-pulp paper used during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are likely to disintegrate within a hundred years. But paper made from linen rags in the fifteenth century can easily last one thousand years or more. The paper found in the Gutenberg Bible is far more stable than that found in any current dime-store novel.

“Not to worry,” he tells Lucille. The Gutenberg Bible will likely reach its one thousandth anniversary. “The book will take care of itself,” he says. He cautions, however, to dust it only once every six months.

The Doheny Gutenberg Bible as it appeared soon after its arrival in Los Angeles in October 1950. The dark spots on the left and right edges of the book are knots of vellum that served as a primitive index system marking different sections of the book.

Alone with the Bible, Lucille begins her inspection. It is larger and heavier than she had imagined. The finished pages measure about sixteen inches tall and twelve inches wide, a size known by experts as a “royal folio.” Even without a magnifying glass she can see that the paper has the watermarks of three different papermakers—a stag or bull’s head with a cross-like star; a bunch of grapes, which falls between the columns of type; and a simple line drawing of a sprig or branch from a tree, which appears on the inner margins. These marks and their variants are found in all the existing paper copies of the Gutenberg Bible17 and can be traced to manufacturers in the town of Piedmont, a region in northwest Italy.18

Every great beauty has a flaw, and Number 45 is no different. Lucille dislikes the three “hideous little knots”19 of vellum that hang along the pages of the Bible’s fore edge. She has never seen anything like them before. In fact, they are a primitive index system, used as thumb markers to identify different sections of the Bible. Such knots are exceedingly rare, and no other Gutenberg Bible is known to have them. She can only guess that in the fifteenth century there had been dozens more attached to the book. Over the decades most had fallen away until now only three remain.

Lucille lingers over the leaves. The first printed page is a universe of its own in terms of sheer beauty. Two dark columns of letters float on a creamy field of paper, perfectly squared. The margins are clean and even with no ragged edges. It is a “miracle of pure mechanics,” Lucille says. She can’t read the Latin of the thirteenth-century text, the so-called Paris version of Saint Jerome’s translation, which was the definitive Bible of the Middle Ages. But she is moved by its careful balance, its presence.

TO APPRECIATE THE “miracle” that captivated Lucille and set so many in pursuit of Number 45, it helps to imagine the conditions that produced those pages sometime before August 1456, in the Rhine River town of Mainz, Germany. Imagination is key, because the story of Johann Gutenberg and his Bible is dominated by ellipses, with unknowns and conjecture far outpacing any certainty. Gutenberg, wittingly or not, wrapped himself in anonymity. Each of his Bibles has more than a thousand pages, but not one is signed, dated, or marked with the place it was printed. No notes about his process, if he made any, survive. And there lies the paradox at the heart of any attempt to understand the history of a Gutenberg Bible. This most famous of books has origins we know very little about. The stories we tell about the man, and how the Bibles came to be, have been cobbled together from a fistful of legal and financial records, and centuries’ worth of dogged scholarly fill-in-the-blank.

The well-accepted version goes something like this: Johann Gensfleischzur Laden zum Gutenberg was born into a patrician family in Mainz around 1400. His father held a position at a local mint, and scholars guess that Gutenberg came in contact with the art of casting gold coins and may have been skilled in goldsmithing and other forms of metalwork.

The leap from there to printing is shorter than it may seem. Goldsmiths were at the center of a creative surge in the early 1430s, and German craftsmen, likely using modified goldsmiths’ tools, were developing techniques for carving images into metal plates, creating a new form of engraving. Like artisans across Europe, they were also searching for ways to create what was known as “artificial script,” a vehicle for producing written text that didn’t rely on the slow, steady, trained hand of the scribe.

Gutenberg was likely part of that search. In 1439, he formed a partnership with three men, promising to teach them proprietary techniques, ostensibly experiments for creating artificial script. Legal papers that document the breakup of the partnership make reference to “formes” and “presses” and “a secret art,” noting that the partners agreed to pay Gutenberg to train them and took an oath promising not to disclose what they learned. There are no records of that time, and nothing documenting what he did afterward. But when he resurfaced four years later, he seems to have been fully prepared to begin printing in a way that represented a striking departure from the past.

Single-page printing had existed for centuries, with the text of whole pages carved into wood, inked, and pressed onto paper. But what Gutenberg developed was a sophisticated process based on the use of single metal letters, which could be combined and recombined to create an ever-changing stream of words. The underlying idea of movable type wasn’t new. It had been tried in eleventh-century China but proved to be unwieldy, given the written language’s thousands of distinct ideograms. The more contained Western alphabet finally made it feasible to consider using single letters, not pages, as the building blocks of mechanical printing.

Gutenberg’s contemporaries had already begun to puzzle out how to make that work, experimenting with carving letters from wood or metal and arranging them into words to be stamped on parchment. The problem was that carving, and re-carving, hundreds or thousands of letters one at a time to produce a book would be extremely time-consuming, and the letters would be subtly different from each other. A scribe could probably go faster and do a better job.

The key was to design and fabricate attractive type that could be produced easily and yield armies of durable letters. That’s what Gutenberg was prepared to do by the time he set up shop in Mainz. His innovation involved carving individual raised letters, or components of them, from metal, punching them into a softer material to create a mold, then pouring in molten metal that would, when it hardened, produce an identical replica. That process, and the fast-hardening alloy of tin, lead, and antimony he developed, would allow practiced fabricators to expediently cast type, which they could melt down and recast as needed.

Printing meant arranging the letters into words, the words into perfectly straight lines, and the lines into even blocks of text to be inked and pressed onto paper or vellum. And each small step of the process, which sounds so mundane today, required invention.

Gutenberg created frames to hold the type in place and fashioned presses from those traditionally used to press olives or grapes. He designed Gothic-looking letters to mimic the calligraphy of the scribes and refined techniques to ensure that even pressure would be applied to blank sheets placed atop the inked, raised type. As well, he located paper that would absorb ink readily and formulated deeply pigmented, varnish-based metallic inks that wouldn’t smear or fade. His ingenious assembly of these elements, and processes for using them, would allow him to create a book that could be reprinted comparatively quickly, easily, and accurately.

His first projects were modest. Several single-leaf papal indulgences—widely used church documents that offered the forgiveness of sins, often in exchange for a “donation”—have been attributed to Gutenberg’s workshop, along with a short Latin grammar book and a lunar calendar.

It is incredible that (as far as we know) just those few initial trials made Gutenberg feel that he was ready to attempt a complete Bible. But a burgeoning market may have pushed him to try. The German cardinal Nicholas of Cusa had recently insisted that all monastic libraries should have a consistent and accurate copy of the Bible, and Gutenberg could likely count on substantial orders from churches, convents, and monasteries. A single handwritten Bible could take as much as two years to produce. Even squadrons of scribes couldn’t hope to satisfy the increasing demand.

Gutenberg’s highly ambitious, learn-on-the-fly project would be a work of 1,200-plus pages using 270 different characters—punctuation as well as upper- and lowercase letters and letter combinations and variations, all designed to mimic the script and space-saving shorthand developed by scribes over centuries. Stephan Füssell, director of the Institute of Book Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, has estimated that the complete printing of the Bible required the casting of an astonishing one hundred thousand individual pieces of type.20

To use them, and turn his press into an assembly line, his workers had to master an array of skills—reading the Latin of the source Bible; rapidly and accurately arranging the type, upside down and backward, in frames to duplicate the text for printing; spacing type line by line and employing the scribe’s art of using hyphenation and abbreviations to ensure that it lined up perfectly in two columns of equal width. Not to mention learning to ink the type, work the presses, and pull clear, unblemished pages, tens of thousands of times.

Number 45 was proof of the workshop’s unlikely success. The artistry that still floated from the page didn’t look like the haphazard work of beginners who would set things right next time. It was uncannily precise, thoughtful in its detail, and beautifully executed. For Estelle and Lucille, the printed pages seem emblematic of the hand of God.

CHAPTER TWO

Treasure Neglected

BUT REVERENCE IS never a given. The four owners Number 45 meets before it makes its way to Estelle’s Book Room are all men of significant means, often with wealth comparable to hers. But the sheen of their libraries sometimes glows brighter than their regard for the ancient texts themselves. Just because they can afford a Gutenberg doesn’t mean they love or understand it. That’s especially true of the first known owner, an Irish-born aristocrat, Archibald Acheson, 3rd Earl of Gosford, who buys the book in 1836.

Gosford lives in an imposing castle, which is the centerpiece of a village known as Markethill in Northern Ireland, and though he is a fanatical collector whose acquisitions fill shelves that reach to a fifty-foot ceiling, he has a curious lack of regard for the Gutenberg Bible, progenitor of the works he vacuums up at auction. Where Estelle Doheny sees a divine hand in its craftsmanship and story, he sees a rather disappointing old book. For him, it is an afterthought, an awkward fit in a collection built around a nineteenth-century sensibility inclined to judge a book in no small measure by its cover.

In an early portrait, Gosford’s intelligent eyes gaze out from a placid face framed by chin whiskers and parted hair that brushes a broad forehead. The son of an Irish Protestant lord whose ancestors are said to have helped James VI of Scotland secure the throne of England in 1603, he is born into a family drawn to talk of literature, often with literary stars of the day. But he sets aside any fascination with character or story when he begins collecting in the 1820s.

Books like Number 45, which had been secreted in the libraries of European aristocrats and monasteries for centuries, have been shaken loose by the French Revolution and Napoleon’s occupying forces, licensed to “requisition” them for the French national library. The chaos of war has allowed tens of thousands of illuminated manuscripts and early printed books—including nine of Gutenberg’s Bibles—to make their way to Britain for the first time. It’s a looking-glass time when Britain’s men of means are buying rare books for sport, going after them with the unhinged intensity that the Dutch once aimed at tulip bulbs.