0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

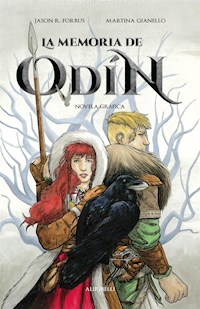

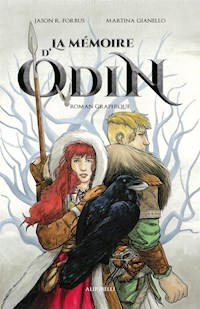

- Herausgeber: Ali Ribelli Edizioni

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

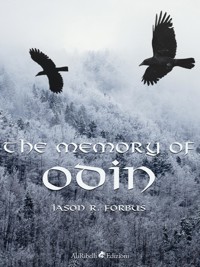

- Sprache: Englisch

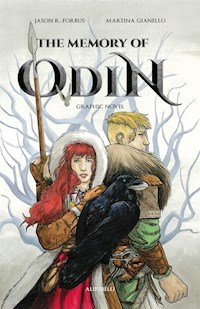

It is the third and final year of Fimbulvetr, the long and cold winter that precedes the end of the Nine Worlds. Midgard lies asleep under a thick layer of ice and snow. The city of men have fallen prey to ravenous wolf packs and bloodthirsty marauders. Gods, trolls and giants ready their weapons and magics for the last battle between Order and Chaos. All prepare for Ragnarok, the ultimate clash of the gods. All except Valhalla, whose tall walls are beset by deafening silence ... No singing or clash of swords can be heard. Sitting on his crumbling throne, Odin sleeps a long and dreamless sleep, waiting for the return of his memory from the inscrutable ocean of the universe and with it his strength to stand up to the Nine World and foster the flourishing of a new beginning.

The book includes an essay on Norse mythology.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

The Memory of Odin by Jason R. Forbus

Graphic design and layout by Sara Calmosi

Inside illustration: Odin enthroned and holding his spear Gungnir, flanked by his ravens Huginn and Muninn and wolves Geri and Freki, 1882, Carl Emil Doepler

Series: Possible Worlds

ISBN 9788833460987

Copyright © 2018 by Jason R. Forbus

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below.

Ali Ribelli Edizioni

www.aliribelli.com – [email protected]

The Memory of Odin

by Jason R. Forbus

AliRibelli Edizioni

Contents

Gods, heroes and giants

The Memory of Odin

Gods, heroes and giants

A short essay on Norse Mythology

Norse mythology evokes images of stormy seas, snowy landscapes, enchanted forests and blood-drenched battlegrounds. Its stories tell of proud and brave warriors, dragons, trolls, dwarves and giants. The cult of Odin and Thor has greatly inspired the fantasy genre – just think of ‘The Lord of the Rings’ by J.R.R. Tolkien and modern role-play games.

But how did it all start?

In the beginning there was the Ginnungagap (literally the ‘yawning void), the cosmic abyss that existed before creation.

At one point, like a sort of duplicate and parallel Big Bangs, at the respective ends of the Ginnungagap two levels of existence were formed: to the north, the frozen Niflheimr and to the south the unbearably hot Múspellheimr. Then from the center of Niflheimr 11 rivers began to flow, the Élivágar.

These rivers came so far from their source that they hardened and formed layers of frost and ice that covered Ginnungagap entirely. But the warm winds of Múspellheimr melted the ice, and from the drops that followed the first beings of the cosmos formed: Ymir, father of the Frost Giants, and Auðhumla, the ‘cosmic cow’ whose milk fed the infant Ymir to a sturdy and godly adulthood.

Of old was the age when Ymir lived;

Sea nor cool waves nor sand there were;

Earth had not been, nor heaven above,

But a yawning gap, and grass nowhere.

Poetic Edda Völuspá, third stanza

Ymir was a wise, but evil being, as all his descendants after him would be. As he stared into the great, lonely void all around him, he resolved not to waste his energies and decided to take a long nap instead. He curled up for the night and soon began to sweat copiously. Each drop of his sweat turned into a giant, and thus that warring race was begotten. But his innate power to create life did not stop there: under his left arm, a man and a woman were born while from his legs came a son with six heads, with the unpronounceable name of Þrúðgelmir.

While Ymir slept, the cosmic cow did not stay idle. You can imagine at that time food was in really short supply, so t the wretched animal had to resort to licking salt that crusted some icy stones. As she licked, on the very first day, towards evening, she brought to light a hair of a man; the following day his head and on the third day the whole person. The man was called Búri (‘the producer’), who generated a son identical to himself who was called Borr (‘the begotten’ – and by the way, food wasn’t the only thing in short supply in those days).

Borr went on to marry Bestla (granddaughter of the frost giant Bölþorn, and what a terrible father-in-law he must have been!) and he had three children with her. The first was named Odin, the second Víli and the third Vé.

One day, just as had happened with Kronos and his children the Olympians, the three gods decided to kill Ymir and to drown in his blood all the giants that he had generated. The sole survivors were Bergelmir, son of the six-headed Þrúðgelmir, and his bride. It is from them that the lineage of Frost Giants would continue.

Following this heinous act, and not knowing how to get rid of the exceedingly cumbersome corpse of Ymir, Odin and his brothers decided to use it to create Midgard (or ‘Middle-earth’, ring a bell?), right smack in the middle of the Ginnungagap. Ymir’s eyebrows became the planet itself, a sort of shelter from the fury of the giants. Instead, Ymir’s flesh became earth, his blood lakes and rivers, his bones mountains, his teeth and the remains of his bones stones, while from his hair grew the trees.

The birth of the dwarves is certainly not as fancy as you would expect: our bearded friends originated from the larvae feasting on the putrid corpse of Ymir (Yuk!). Not fully satisfied with the level of eeriness of their art work, the gods placed Ymir’s skull above the Ginnungagap and thus created the heavenly vault, supported by four dwarfs (hope they get some days off every now and then). Their names were: Norðri, Suðri, Austri and Vestri, and just so you know the cardinal points are named after them.

Odin then placed one of Bergelmir’s sons, the shape-shifter Hræsvelgr, at the end of the earth. The giant transformed into a giant eagle, and began to powerfully flap its wings, generating the wind that crosses the world in all directions.

With the bones taken care of, the gods went on and pulled poor Ymir’s brain out and broke it into several pieces these they tossed in the air like confetti that transformed into puffy clouds (think about that the next time you are lying on the grass looking at the heavens and marveling at the clouds).

Lastly, they collected the sparks from Muspellheimr and spread them all across the Ginnungagap, creating the light and the stars.

Norse cosmology is comprised of 9 worlds (Nío Heimar in Old Norse). Except Midgard, which roughly corresponds to Scandinavia, the remaining eight worlds can be divided into pairs of opposites: the aforementioned Múspellheimr and Niflheimr, fire and heat vs ice and cold; Asaheimr and Hel, which can loosely be interpreted as Christian Heaven and Hell; Vanaheimr and Jötunheimr, creation and destruction; Alfheimr and Svartálfaheimr, light and darkness.

All these worlds are connected to each other by the Tree of the World, Yggdrasill.

An ash I know there stands,

Yggdrasill is its name,

a tall tree, showered

with shining loam.

From there come the dews

that drop in the valleys.

It stands forever green over

Urðr’s well.

Poetic Edda Völuspá, second stanza

According to the most widely accepted interpretation of the myths, the branches of Yggdrasill would extend far into the heavens, while the tree would be supported by three roots that extend far away into other locations; one to the well Urðarbrunnr in the heavens, one to the spring Hvergelmir, and another to the well Mímisbrunnr.

The importance of Yggdrasill in Norse Cosmology is further highlighted in the Poetic Edda Völuspá, the ‘Prophecy of the Völva’ (‘Seeress’ in Old Norse):

I remember nine worlds,

nine in the tree,

the great measuring-tree,

down in the mould.

But what about the gods and supernatural creatures that populate Norse mythology? The deities are divided in two classes: the Æsir and the Vanir, the latter less known and somehow subordinate to the former. The distinction, however, is not clear: in the distant past the two factions faced each other in war but later agreed to peace, exchanged hostages and even joined in marriage. Moreover, membership to one of the two classes is not crystal clear for some deities.

One thing that Æsir and Vanir have in common is their general hatred of the Jötnar (singular Jötunn). The Jötnar are a type of entity contrasted with gods and other figures, such as dwarves and elves. The entities are themselves ambiguously defined and variously referred to by several other terms, including troll. Trolls may be ugly and slow-witted, or look and behave exactly like human beings, with no particularly grotesque characteristics about them.

Generally speaking, the Jötnarare not necessarily notably large and their features range from great beauty to astonishing grotesqueness. It should also be noted that both the Æsir and the Vanir can join with Jötnar to generate children, when the latter are not monsters. Indeed, some deities such as Skaði and Gerðr, are themselves described as Jötnar, and various well-known deities, such as Odin, are descendants of the Jötnar.

As for the giants, here too we are presented with two general classes: the Hrímþursar, the ‘giants of hoarfrost’, and the Múspellsmegir or ‘fire giants’ also called ‘Sons of Muspell’. Whether you like your tea cool or hot, giants are presented as element-based creatures, and should therefore not be confused with trolls. In fact, while giants tend to live in clans and take an active role in Norse Mythology, especially in regards to their interaction with gods and humans, trolls tend to live in isolatation and avoid any involvement in the affairs of humans and divine beings alike.

Other well-known supernatural beings are Fenrir the wolf and Miðgarðsormr, the great serpent that surrounds the world of Midgard. Both are the children that the trickster god Loki had with a giantess. Other creatures often mentioned are Huginn and Muninn, respectively ‘thought’ and ‘memory’, the two ravens that keep Odin informed about everything that happens in the Nine Worlds. Sleipnir, Odin’s eight-legged horse, is also a son of Loki (the art of lying makes him a true Casanova with the ladies).