6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

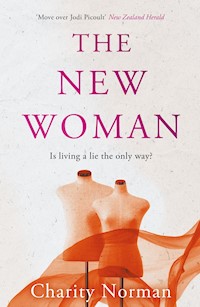

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

*A BBC Radio 2 Book Club Pick 2015* 'A poignant tale of one person's transgender journey.' - Heat Luke Livingstone is a lucky man. He's a respected solicitor, a father and grandfather, a pillar of the community. He has a loving wife and an idyllic home in the Oxfordshire countryside. Yet Luke is struggling with an unbearable secret, and it's threatening to destroy him. All his life, Luke has hidden the truth about himself and his identity. It's a truth so fundamental that it will shatter his family, rock his community and leave him outcast. But Luke has nowhere left to run, and to continue living, he must become the person - the woman - he knows himself to be, whatever the cost. 'Move over Jodi Picoult. New Zealand-based author Charity Norman has the same clever knack of taking an issue and examining it from all angles, to see the effect it has on everyone involved.' New Zealand Herald

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Also by Charity Norman

Freeing Grace

After the Fall

(Published as Second Chances in Australia)

The Son-in-Law

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Allen & Unwin

First published in Australia in 2015 by Allen & Unwin

(under the title The Secret Life of Luke Livingstone)

Copyright © Charity Norman 2015

The moral right of Charity Norman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Fax: 020 7430 0916

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.atlantic-books.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 74331 875 1

E-book ISBN 978 1 92526 671 9

Typeset by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

Printed in Great Britain

For Petra King, with my thanks and admiration.

What are little boys made of?

Slugs and snails, and puppy dogs’ tails.

That’s what little boys are made of.

What are little girls made of?

Sugar and spice, and all things nice.

That’s what little girls are made of.

Traditional nursery rhyme

Contents

PROLOGUE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

THIRTY-FOUR

THIRTY-FIVE

THIRTY-SIX

THIRTY-SEVEN

THIRTY-EIGHT

THIRTY-NINE

FORTY

FORTY-ONE

FORTY-TWO

FORTY-THREE

FORTY-FOUR

FORTY-FIVE

FORTY-SIX

FORTY-SEVEN

FORTY-EIGHT

FORTY-NINE

FIFTY

FIFTY-ONE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Let me tell you a story. Please hear me out, because it will not be easy for me to tell, nor for you to understand. What happened was the last—the absolute last—thing I expected. I never saw it coming until it smashed into my life. I need you to see why I did as I did. I need you to walk in my shoes.

There was once a girl called Eilish French. She was a noisy child, with a bird’s nest of hair and socks around her ankles. Her parents divorced bloodily and expensively when she was very small. Though they loathed one another by the time their private war was over, both of them doted on their only child. I’m afraid she was rather spoiled. In those days she wanted to be an air hostess. Then she thought perhaps she would be a pilot, or a brain surgeon, or a film star, or possibly a nun. Each dream gave way to another, and each was abandoned. In the end, she landed a job in marketing at much the same time as Margaret Thatcher arrived in Downing Street.

Eilish attacked her career with a ruthlessness that shamed her later when she thought back on it. A trade magazine described her as a rising star. Her long-term boyfriend, who was a stockbroker, said rising stars had no time for him and found someone who did. Her mother berated her for her carelessness in losing a very eligible man, but Eilish wasn’t sorry to see him go. She could not shake off the feeling that she was in limbo, waiting for something.

And then she met a young solicitor called Luke Livingstone, and knew that the waiting was over. Everyone at the wedding agreed that they were a golden couple, sure to live Happily Ever After; and so it seemed to be. As the decades passed they became parents and even grandparents. Life wasn’t all plain sailing, but there was enough love and laughter to carry it along. After all, what marriage is ever without its rough weather? Luke succeeded in his own career, and she forged a new one. It brought her far less income—but far greater satisfaction—than marketing ever had. They lived in a picture-book house. Their pond was a haven for wild ducks; their kitchen a haven for lame ones, who found warmth around its table. At weekends the place rang with the sounds of friendship and conversation.

Girl meets boy. They fall in love, and they marry. That should have been the end of the story.

For thirty years they shared one another’s lives.

Thirty years.

Thirty.

I thought I knew that man. I thought I had been shown into every corner of his mind, that he’d shared every fear, every hidden longing. I thought he kept no secrets from me.

Turns out I never knew him at all.

This is his story. And mine.

One

Luke

She answered on the fifth ring, breathy because she’d rushed in from her mowing. I imagined her in gardening clothes: those faded jeans that still fitted as though she were twenty years old, and one of my old shirts, her auburn hair tied up in a silk scarf. My beautiful wife.

‘On the train now. I’m finished in Norwich,’ I said.

‘Wonderful!’ She sounded happy. It made my heart ache. ‘So you’ll be home for supper?’

I had my story planned. ‘Look, I’ve got too many emails marked urgent. I think I’d better stay at the flat tonight, go into Bannermans tomorrow and tackle the backlog.’

‘You all right?’ she asked.

‘Fine.’

‘Tired?’

‘Not really.’ I rallied myself. ‘So, school term has ended! How was your—’

A blast of sound rocked the carriage as we shot into a tunnel. The mobile connection was broken. I’d lost her. I would call again later, and find some way to say goodbye.

The train was half empty. Diagonally across from me, sharing my table, an elderly woman frowned at a crossword. And, of course, there was the man in the window. He filled my peripheral vision, floating just beyond the inky glass. I knew he was watching me: middle-aged, middle everything in striped shirtsleeves and a tie; dark hair, now a little grey, sweeping above his ears. Neat features. Good looking, according to Eilish and Kate, though to me he’d always been grotesque. When I turned my head, my eyes met the cavernous ones in the black mirror. We stared at one another in mutual dislike. Not long now, I thought with triumph. I’ll be rid of you forever. Then the tunnel ended, and the grey ghost faded into a grey sky.

There were things to be done. Final things. I dug in my briefcase for writing paper and fountain pen. Neither my mind nor my eyes wanted to focus, but I made myself concentrate. I owed my family that. I had one last letter to finish. It was to my Kate: twenty-two years old, pierced in nose and navel; the most precious young woman in the universe.

I hope you find as much love and happiness in your life as I have with your mother. You have been my joy. Do not change, darling daughter. Do not underestimate your gifts. You have the power to make the world a better place.

I’d crossed out two versions and begun a third when the train checked, slowed, and halted. Silence. The scratching of my pen seemed much too loud, so I put it down. Across the aisle a young fellow in a suit kept rattling his packet of crisps. It’s a sound that annoys Kate intensely; if she’d been in my seat she might have leaned over and snatched them out of his hand. The woman across from me seemed to feel the same, because she clicked her tongue at every crackle or crunch.

Minutes passed. The temperature rose. The crisp packet rattled. At last the guard’s voice thundered over the intercom: it was a signals failure, apparently. He would like to apologise on behalf of Anglian Trains.

‘Doesn’t sound very apologetic,’ remarked the woman. Her hair was absolutely white. A jacket and beret—in matching crimson velvet—lay on the seat beside her. We shook our heads, and I said, ‘Good old British Rail, come back, all is forgiven.’ Similar sentiments were murmured all around the carriage as strangers united in their irritation. I loosened my tie and said I was going to get a drink from the buffet, and would she like anything?

She thanked me in the over-loud voice of the chronically deaf, reaching into her handbag. ‘What a very civilised idea. Gin and tonic, please.’

By the time I returned, crisp-packet boy had donned a set of headphones and shut his eyes.

‘Are you being met?’ I asked my table-mate, as we poured our drinks. ‘You’re welcome to use my phone, if you need to contact anybody.’

‘No, no. I shall hail a taxi.’ She opened a tiny case, took out two hearing aids and slid one into each ear. They whistled as she adjusted them. ‘You don’t see those nowadays,’ she said, nodding approvingly at my gold pen. ‘Proper fountain pens. Proper ink.’

I smiled at the pen. ‘This was a present from my children. It’s an old friend. They had my name engraved on it, see?’

I pictured Kate and Simon—young then, perhaps twelve and eighteen. They’d wrapped up my birthday present and tied a blue ribbon around the parcel. I still kept the ribbon in a drawer of my desk.

I wished there were another way. I wished I didn’t have to leave them.

My companion pulled her knitting from her bag, rolled wool around one finger and began to click at high speed. She talked and knitted, chuckling fondly as she described her great-grandchild Henry, and rather less fondly when it came to Henry’s parents, who—she said—cared about nothing but material possessions. She herself was eighty-nine years old, and had been a teacher all her working life.

‘My wife’s a teacher too,’ I said. ‘Special needs. In a secondary school.’

‘Is she really? That’s enormously valuable. Aha!’ The carriage had jerked, and was inching forwards. ‘We may get to London today, after all.’

I may get to die today, after all.

‘What’s it going to be?’ I asked, nodding at her handiwork.

‘This? A jersey for Henry. He’d much rather be in a sweatshirt, I expect. With a hood, so that he can go rioting and not be recognisable on the closed-circuit cameras.’

I laughed at this, and she looked pleased. ‘You have a family?’ she asked.

‘Two children.’ Three children, I always think; but I never say it anymore. People ask what they’re doing now, and I have to explain about Charlotte, and can see them thinking, But she was only a few minutes old! Why count her?

‘Still at school?’ asked the woman.

‘Good Lord, no! Our second grandchild is on the way.’

She raised her eyebrows. ‘You look young to be a grandparent.’

‘Eilish and I will have been married thirty years come October.’

‘Ah! The pearl anniversary.’

I felt my darkness deepening. ‘She’s planning a party to celebrate. Marquee, band, fireworks. Half the world’s on the guest list. The invitations will be going out any day.’

‘Lucky man.’ Milky blue eyes were fixed on me as she knitted. Loop, click, another loop.

‘Yes. Lucky.’

‘You don’t sound at all enthusiastic.’

I tried to summon the energy to protest, to insist that I was hugely looking forward to the Big Event; but I hadn’t the will. I felt transparent. Perhaps she knew what I was.

A stranger on a train. There was nobody I could possibly have told except a very old woman I’d never seen before and never would again.

‘I won’t be there,’ I said. ‘If all goes to plan I’ll be gone by tomorrow morning. This signals failure on the line has prolonged my life.’

Her fingers stopped moving. ‘May I ask why?’

‘Because it’s time. Because I have come to the end of a very long road.’

‘But you have a choice. There’s no need for such drastic measures.’

I drained my drink. It felt rough at the back of my throat. ‘You were right when you described me as a lucky man,’ I said, and coughed. ‘Lucky, lucky. Everyone knows that. People kept telling me so on our wedding day—looking shocked, as though I’d somehow tricked her. Actually, it’s true: I did trick her. Eilish French could have married anyone at all, but for some reason she chose me. Look—hang on . . .’ I felt in the pocket of my jacket and pulled out a black and white photograph.

I’d taken the picture on a winter’s evening when I’d just walked in from work and stopped in the doorway of the study. Her head was bent over some child’s handwriting, her cheek freckled, her hands strong and sure. A coppery lock of hair had escaped from its velvet tie and brushed her mouth. It was one of many moments in our life together when I’d felt overwhelmed at the very sight of her. She had music playing on the stereo and the room seemed to swell with sound. I could still hear it, rippling across the rattle of the train. I hummed the melody under my breath. Debussy. It poured into me. It made me want to weep.

The woman put on her glasses to look. ‘Ah, yes. Beautiful,’ she said, before handing the photo back. ‘I suppose you’re having an affair. How very mediocre.’

‘Worse. Much worse. I’ve been acting a part since the day we met. I’m not who she thinks I am.’

‘Who are you, then?’

‘I’m . . .’ No. I couldn’t tell her. My secret shame was too monstrous. ‘Take my word for it. If Eilish knew the truth, it would destroy her.’

‘Whereas your suicide will shower her with blessings?’

‘You think I’m selfish. A selfish coward.’

‘Hmm.’ She considered the suggestion, her head tilted to one side. After a moment she began counting rows, two by two, and I went back to staring out of the window.

I was the birthday boy, five years old, standing at the top of the very tall tree in our front garden. I felt the trunk sway in the wind but I wasn’t frightened. I’d skinned my knee on the way up. A trickle of blood was snaking its way down to my sock. I could see across the garden, across the barns, right to the far end of the farm. They were having a party for me, down there in our house. My mother had invited all the boys in my class at school. I’d run away. I didn’t want the party. I didn’t want the boys. I didn’t want to be me.

Then she found me. I could see the white oval of her upturned face, hear her voice high with panic. Luke! Oh dear God, dear God. Hold tight!

Something was whispering in my ear. You don’t have to hold tight, it said. You could just let go. In my imagination it was a mummery figure with a red butterfly mouth. That was my first encounter with The Thought, and it stayed with me from that moment on. Other children had imaginary friends who tempted them to steal biscuits; mine nagged me to run in front of a lorry, or turn one of Dad’s guns on myself. No more, it whispered each morning when the lonely child—the anxious adolescent—the despairing adult—opened his eyes and contemplated a world in which he didn’t fit. No more being Luke. No more being, at all.

It was whispering to me right now, as I sat on the train.

‘Don’t give up,’ said the woman across the table. I’d forgotten she was there.

‘You’re trying to be kind,’ I said. ‘Thank you. Thank you for your kindness, but you know nothing about me.’

‘Perhaps I know something about how your wife will feel.’

‘This is the best thing I can do for her.’

‘I doubt it.’

I leaned closer, wanting her blessing. ‘It’s the right time,’ I said. ‘My father’s died. He needed me, so I stayed; but now he’s gone. Our children are grown up. Eilish is a strong woman, and the finances are all arranged—she’ll be able to live very comfortably.’

The woman looked severely at me, her brows drawn. ‘Think of the poor person who has to scrape you off the railway line, or fish you out of the Thames.’

‘No, no,’ I said. ‘I’ve thought of that. I’ve everything I need in our flat in London. It won’t be messy. I’ve planned a way to make sure I’m found by someone who won’t care. He’s ex-SAS.’

‘Even ex-SAS soldiers have feelings, I expect.’

‘Not this one. And especially not about this, because he doesn’t like me very much.’

She completed several more rows of knitting before she tackled me again. ‘You’re not quite sure, though, are you? When you spoke before of your family, of your wife . . . there’s ambivalence. I can hear it.’

She was right. My family. Eilish. I felt something blocking my throat.

‘My husband once made a mistake,’ said the woman, laying down her knitting. ‘He worked for a charity. He cooked the books; embezzled money to pay our children’s school fees, though he never told me we were struggling. They could have gone to the local school, for heaven’s sake, it wouldn’t have been the end of the world! He meant to pay everything back, his ship would soon come in, but it never did. He thought of the disgrace he was bringing on all of us, of prison; he imagined what the newspapers would print. Those thoughts possessed him. So he drove his car to an isolated spot and piped the exhaust through the window.’ She reached into her bag, took out a flowered handkerchief and pressed it to her nose.

‘I’m so sorry,’ I said.

‘So was I. So were our children. So were his poor mother and father. He was thirty-eight years old. Do you think we were grateful? Do you think we cared two hoots about the money when we buried him? Would I have cared now, aged nearly ninety?’

‘No.’

‘We didn’t. We didn’t.’ I could hear her anger, still raw after all these years. ‘I dare say it would have been grim—possibly I would have divorced him, though I doubt it—but he would have been alive to give his daughter away on her wedding day. Don’t you want to accompany your daughter up the aisle on her wedding day?’

I smiled, despite everything, at the unlikely image of Kate in a white veil. ‘She’s not that kind of girl.’

‘Mine was, but her father wasn’t alive to see her married. He couldn’t see any way out. That’s what he said in his letter. No way out. No choice.’ She shook her forefinger, admonishing the long-dead husband. ‘If he’d asked me, I would have told him! There are always other choices.’

‘Not for me.’

‘Yes, for you!’ Her voice was almost a shout. ‘It’s been fifty years since Jonathan left me. My children, my grandchildren . . . all of us haunted by that one terrible act. His parents never recovered. They died in grief. When I see him at the pearly gates, I’m going to give him a damned good kick up the backside.’

‘I’m sorry. I really am.’

Her eyelids came down for a second, heavily, as though I’d bored her. ‘Have you murdered somebody?’

‘No.’

‘Have you raped or maimed or tortured anyone?’

‘No.’

‘Well, then. Whatever your “crime”, your wife has the right to know about it.’

The unshed tears of decades began to scald my eyes. Eilish was my closest friend. She knew me better than anyone in the world. I longed to confide in her.

‘She’d think me a monster,’ I said.

‘Are you a monster?’

The door at the end of the carriage slid open, and a guard came noisily click-clicking. ‘Tickets, please; all tickets, please.’ He woke crisp-packet boy. The woman tucked her anger away, attacking the knitting with pursed lips. I finished my letter to Kate, slid it into an envelope and wrote her name on the outside.

When the train pulled into Liverpool Street, I stood up and lifted our bags from the rack. Hers was small and very light. She thanked me coolly as she put on her jacket.

‘Let me carry your case to the taxi,’ I said.

‘Don’t leave that beautiful woman alone. Don’t leave her with unanswered questions. And anger. And guilt. She deserves better. Take it from someone who knows.’

It took quite a while to get up the platform and past the barrier. The station was packed with Friday travellers, and my companion was alarmingly shaky on her feet. She used a stick, but even so I was afraid she was going to tip right over. I saw her to the covered rank and waited with her until we were at the front of the queue.

I was helping her into a taxi when she gripped my forearm. ‘You will continue living? Promise me.’

I had no answer. No promise.

‘There’s a drain,’ she said, lowering herself into the seat. ‘There, by your foot. Drop the keys to your flat down there. Buy yourself a little more time.’

I thanked her, and we said goodbye. I stood irresolute as her cab drew away. Three women waited in the queue behind me. They were dressed to the nines, perhaps for the theatre: sparkling earrings, high heels, swirling skirts. I caught a puff of scent mingling with exhaust fumes, hot tarmac and midsummer dustiness. Their heads were bent together in easy intimacy—if you watch a group of women together, you’ll see that they manage this as men cannot—talking very fast, never quite finishing a sentence; never needing to, it seemed. Suddenly all three burst into helpless laughter, and I felt the familiar agony of envy.

The rope was waiting for me. I’d already made it into a noose, already tied the knots in exactly the right way. It’s amazing what you can find on the internet: step-by-step guides to suicide by every possible method. I had an email ready to send to Bruce, the retired SAS man turned property manager who might or might not have feelings. I’d be long, long gone before he found me.

The next taxi was mine. The journey would take no time at all. Within an hour, I’d be free.

Now was my time. Now. Tonight.

I reached into my pocket to turn off the phone. I couldn’t bear to hear her voice now. Two black cabs pulled in from the road, and the first stopped in front of me. I took hold of the door handle. I could feel the vibration of the engine under my fingers.

All around me, life roared and rolled. The three women waved at the second taxi. I glimpsed a flurry of heels and skirts as they threw open the door and piled inside. My driver looked out and spoke to me.

‘Sorry?’ I said.

He spoke again, but I heard no words. The sky was billowing. I saw Eilish in the garden, among the roses. She had a silk scarf in her hair, and she was alone. She was alone.

Out on the road, it had begun to rain.

Two

Eilish

I felt the first drops of rain speckle my arms. It was a gentle, happy sensation; a caress.

When the mower ran out of fuel I made a cup of tea, carried it out to the terrace and settled myself on the wooden bench. Honeysuckle grew in fragrant clusters up the old wall of the barn. A tendril dipped into my mug, but I didn’t mind. The air was rich with the scents of summer, intensified by wet. Life was good. School term had finished at last. I’d spent the afternoon in the garden, demob-happy amid peace and grass clippings.

Luke made the bench about twenty years ago, when the children were small. Sitting there, leaning against the wall, we could keep an eye on them without spoiling their fun. They and their gang built dens in the bushes beside the pond; we could hear giggling over naughty songs, and the war cries of pitched battles. Beyond the terrace, birds darted around the claret leaves of a maple. Charlotte’s tree. One day, we’d told each other as we tucked it into its bed of soil, it would be magnificent. Charlotte’s great-nephews and -nieces would hang their swings from its branches.

Luke had phoned from the train, to say that his conference was finished. He was cut off in mid-sentence—a tunnel, probably. He hadn’t called back, but I hadn’t really expected him to. He hates public phone conversations, doesn’t like to draw attention to himself. All the same, something in his tone—a heaviness—unsettled me. I’d call ours a very happy marriage, but Luke hasn’t always been a very happy man.

Rubbish. I shook myself, spilling tea. Why should he be in trouble now? Life couldn’t be better! The mortgage was paid off, the children safely launched into adulthood. We were planning a fabulous party, to celebrate thirty years of marriage. Best of all, he and I had organised three months’ leave next spring, to be spent in a villa in Tuscany. I told myself these things, and stubbornly ignored the grasping chill in my stomach.

All at once, the heavens opened in earnest. Drops were splashing into my mug. I gave up on the lawn and took refuge inside, slipping off grass-clogged shoes as I stepped through the folding doors into the kitchen. I tried Luke’s phone, hoping he might be at the flat by now, but got his voicemail. He was probably on the tube.

The air was warm despite the rain. If Luke had been home, we’d have shared a bottle of wine and sat out on the bench with an umbrella each. He always said we were like two old peasants in front of their log cabin. Never mind: I’d never been afraid of solitude, and tomorrow would come soon enough.

The sky darkened. The rain was relentless.

Kate

She couldn’t believe her eyes.

‘Bastard!’ she yelled, glaring at the screen. ‘You thieving, backstabbing prick.’

The cash-dispensing machine wasn’t offended. It asked her if she’d like another transaction. No, she told it, she didn’t want another frigging transaction, she wanted her money. Then it spat out her card.

There was some guy waiting in the queue behind her. She could hear him chuckling, and his face was reflected in the screen. He had a ridiculous moustache. What was it with losers and moustaches?

‘Overdrawn, eh?’ he remarked, as though he and she were good mates.

Jerk alert.

‘Looks like you overdid the spending on your holiday,’ he said. ‘Too many piña coladas in nightclubs.’

‘Go stuff yourself.’

There was a wounded silence before he muttered, ‘No need to bite my head off.’

‘No need for you to be a patronising tosspot,’ she retorted, and stomped off to the luggage carousel, where she could see her backpack gliding through the rubber strips.

Moustachio had obviously used both his brain cells to think up an insult, because he sidled up to her as she was heading for customs. ‘Watch you don’t set off the metal detectors,’ he said narkily, ‘with all that hardware on your face.’

She didn’t have hardware on her face. She had one garnet stud in her nose. Just one. It was a lot less offensive than wearing half a hedgehog on your upper lip. She held up the middle finger of one hand. With the other, she was writing a text:

WTF happened to the bank account???

She sent this message while walking past the mirrored walls of customs. She imagined uniformed officers, rubber gloves at the ready, watching beadily. Or perhaps they weren’t; perhaps they were drinking coffee and playing cards while thousands of people streamed past, pulling suitcases stuffed full of heroin and exotic birds.

Owen’s response made her jaw drop. Took your share of the rent.

She stopped dead, firing off her reply. Bollocks!! I haven’t been there for weeks.

U never gave notice so am entitled. I have ur stuff in bin bags. Pls collect asap as its in my way. Also extensive damage to my shirt. Vet bills. Welcome home BTW.

So. After two years, their grand love affair had come to this. It wasn’t so long ago that she and Owen couldn’t spend more than a night apart without phoning one another and babbling. They were like an old married couple—like Mum and Dad, come to think of it—until it all went wrong. She’d hoped to patch things up when she got home from Israel but, God almighty, she wanted to kill Owen now. She was thinking about exactly how much she’d like to kill him as her thumb hit the keys.

VET BILLS???

He was really enjoying himself.

Baffy got chicken bone from bin pierced gut infection almost died emergency surgery cost a fortune. Ur dog too remember?

Well, that was true. Sort of.

She was out, and into the arrivals hall. Not being met at Heathrow, she reflected bitterly, makes you feel like a spare prick at a wedding. Everyone else seemed to have fans yelling at them from the barriers. She was almost knocked over by a family who’d begun crying and throwing their arms around one another; then she had to step around a snogging couple. Get a room. It was like being an extra in the opening sequence of Love Actually.

She’d taken that flight, a day earlier than those of the others on the dig, because it got her home in time for Mathis and John’s party. She was regretting this decision as she headed for the train. She loved Mathis and John, and she loved a party, but she’d been sleeping in a tent for six weeks and had no clean clothes. It had been a long flight followed by an emptied bank account. The last thing she felt like doing was staying up all night, getting ratted, and passing out on a sofa among the empties.

She found a seat on the platform and perched like a turtle, her pack still on. Then she scrolled down to her father’s mobile number. It would do her good to moan about Owen, and Dad was the man for that. He and Kate had an ancient alliance. Dad could be counted on to toe the party line and agree that Owen was a sociopath. Her mother had a bad habit of demanding details, maybe even—heaven forbid!—suggesting that Kate could be in the wrong.

‘This is Luke Livingstone’s phone. Press four if you would like to be put through to my direct line at Bannermans. Otherwise, do leave a message.’

Kate smiled to herself. Lovely Dad, so courteous and gentle. Some of Kate’s friends found her father too reserved, but he wasn’t at all. Quite the opposite, when you were his daughter.

She rang home, hoping he would answer the phone.

‘Eilish here.’

Bugger. ‘Hi, Mum. Bit of a rush, I’m just—’

‘Darling! Where are you?’

‘Still at Heathrow.’

‘How was the dig?’

‘Fascinating. Hot. I’ve got hundreds of photos, I’ll bore you with them when I see you. Um . . . is Dad there?’

Kate could tell her mother was multi-tasking, filling the kettle, probably with the phone jammed under her chin. ‘He’s staying at the flat tonight,’ she said. ‘But I expect you’re rushing back to Owen, are you? Or did he meet you at the airport?’

Kate thought about Owen’s place, and the bin bags with her things stuffed into them. He’d be hanging around like a moray eel under a rock, waiting for her to turn up so that he could play mind games. Suddenly she wanted to be at home again, wearing fluffy socks, drinking tea in the kitchen with her mum and chortling at Blackadder with her dad.

‘Um . . .’ she said. ‘I might come home tomorrow. I have to be there Sunday anyway, don’t I, when we plant Grandad’s tree? I’ll just arrive a day early.’

‘Terrific! Wonderful! And Owen too?’

‘No.’

‘He’s very welcome.’

‘He can’t get away from work.’

Kate could hear her mother’s antennae whirling around. That woman had some weird telepathic gift. When Kate had first lit up a cigarette, at the age of thirteen, she knew immediately. Kate had no idea how, because she’d gargled for about ten minutes with minty mouthwash, but Mum went ballistic and stopped her pocket money for a month. Her own father had died of lung cancer, so perhaps it was fair enough. When Kate was being bullied at school, she guessed that too, and went storming off to see the class teacher. It made things worse, but Kate appreciated her going into battle.

‘All well between you and Owen?’ Eilish asked now.

‘Sorry? The train’s coming in. Can’t hear a thing.’

Eilish started bellowing like a foghorn. ‘CAN . . . YOU . . . HEAR . . . ME . . . NOW?’

‘It’s no good, I’ve lost you. I’ll phone tomorrow. Bye, Mum.’

Bloody typical, Kate thought sourly as she lurched down the carriage, smacking people in the face with her backpack. Owen’s a saint in her eyes. He can do no wrong, even though he’s a total dildo.

It was her last coherent thought before she fell asleep with her head on the shoulder of the Japanese tourist in the next seat.

Three

Luke

Rumbling. A train, passing beneath my feet. The keys were cutting into my fist. They were my certainty, in the darkness and rain. I needed them because everything was ready in the flat. I wasn’t afraid of dying, you see. I was afraid of living.

I hadn’t got into that black cab. I’d let go of the door, stumbled out of the station and into the rain. Now I had no idea how long I’d been walking, and I didn’t care. What did time matter? I was non-existent in the bustle of humanity. I felt so much like a ghost that I accidentally collided with a group of city suits as they stood smoking, huddled under a dripping canopy outside one of the bars near the Barbican. Bless them, they were in a jovial weekend mood. They assumed I’d had one too many; they even offered me a cigarette.

Indecision was tearing at me. I would shatter Eilish by my death or by telling her the truth. Either way, I would lose her. There were no other options. You might find that impossible to understand, but, believe me, there were none. I had twisted and turned and come to this final, inescapable conclusion.

The pubs emptied; the traffic thinned. Blocked gutters became muddy streams through which I waded. People eyed me as I walked past, puzzled by my saturated clothes and aimlessness. My overnight bag was slung over one shoulder, my briefcase in the other hand. They felt more and more heavy. I thought of dumping the overnight bag into a skip, but there were things in it that I didn’t want to be found. If I was going to end my life tonight, I must dispose of them more carefully.

It was long after midnight. There was a blister on my right heel, but I limped on. The night buses were carrying Friday-night revellers home, windscreen wipers flicking, when I turned into Thurso Lane.

Well done! purred The Thought. Its voice was affectionate and understanding, as though coaxing a tired toddler on a long journey. Nearly there. Soon you can put down those things you’ve been carrying. You can let go of the tree, at long last.

The rain was a torrent as I walked down the basement steps. I dropped my bags beside the dustbin. The security light flickered into life, glinting on falling drops. Water coursed down my face.

I fitted my keys into the locks. The bottom deadlock first, and then the Yale.

‘This is it,’ I said out loud.

I’d made my choice. I wouldn’t see how Kate’s life turned out, or Simon’s. I wouldn’t see my grandchildren grow up. I wouldn’t grow old with Eilish. Perhaps she’d be angry for the rest of her life, like the woman on the train. It was better than the alternative. Probably.

The Yale turned with a quiet click. The door gave way under the pressure of my hand. The security light went out.

Four

Eilish

After Kate rang off, I danced a little jig. Well! This sounded like very hopeful news. Luke and I disliked Owen more every time we saw him, though we made herculean efforts to hide the fact. There was something infuriating about the boy’s mousy nondescriptness. Kate was a free spirit and yet he tried to stifle her with his manipulative poor-me-I’ve-had-a-rough-childhood clinginess. He’d even brought a crazy little dog home from the RSPCA, in a blatant attempt to play mums and dads. Kate took the bait (‘He’s never had any happiness, Mum’) but Luke and I saw right through the ploy. Our abiding terror was that a real baby would be coming along next.

The whole thing was baffling. Ever since adolescence, Kate’s been a feminist of the old school. If Owen had been a rugby-playing banker with a square chin and a Range Rover, she wouldn’t have touched him with a barge pole. It seemed ironic that she’d let a needy, controlling boy rule her life just as surely as any bullying mobster.

I hummed a few bars of ‘Goodbye Yellow Brick Road’ as I tipped salad out of a bag and warmed up yesterday’s lasagne. Mm-hm! Owen was on his way out, all right. I couldn’t wait to tell Luke the glad tidings when he phoned.

But he didn’t phone. Every half-hour or so I tried his number, only to get voicemail. Maybe his battery was flat. His charger was here, in the kitchen.

After supper I opened my roll-top desk and designed the invitations for our party. By midnight I still hadn’t heard from Luke, so I turned in. I read for a while in bed, wearing the honey-coloured silk slip he gave me on our last anniversary. He actually bought it himself, in the lingerie department of House of Fraser. Now, that shows real courage! A lone man, an alien among all that underwiring and cleavage-boosting, tackling false-eyelashed assistants. He’d been so pleased with himself.

After turning out the lamp, I reached across to his side of the bed and pulled his pillow under my head. I always stole it when he was away. It smelled of him: deodorant, soap and . . . Lukeness. It was the next best thing to cuddling the man himself.

A thousand tiny streams were rippling across the skylight. Putting the window directly above our bed was one of the few things Luke had insisted upon for Smith’s Barn. ‘I’ll lie and look up at the stars,’ he said. ‘Insomnia will be a privilege.’

I was sinking into the depths of sleep when my bedroom door creaked.

‘Don’t you dare, Casino,’ I whispered. ‘Master isn’t home.’

A weight landed on my legs, followed by kneading and enthusiastic purrs. Bloody cat. Ah, well. It was nice to have the company. I reached onto the bedside cabinet for my reading glasses and checked my phone yet again. No text. No missed call. Not to worry. Luke would be asleep at the flat by now. My stomach grew a little colder.

For a long time, I lay gazing through the watery glass at the blurred glow of the moon. Our bedroom was small and misshapen, crammed under the sloping roof of the barn. Charlotte was born in this room. On this bed. Died here too, a few minutes later. Luke and I also seemed to die for a while. I can understand why tragedy breaks couples apart: agony obliterates love for a long, long time. We stayed together, though. In the end we had a deeper understanding, because we’d shared despair.

A burst of raindrops spattered onto the skylight. I could just make out his cable knit sweater and a pair of jeans, shadows in the milky light, hanging over the footboard of the bed. These were the clothes he’d been wearing the day before he left, when we took the path across Gareth’s farm. We wandered side by side in the familiar landscape, close together, our hands sometimes touching. The fields were dotted with cotton-reel bales. We were leaning on the handrail of the footbridge, watching the slow passage of the stream, when Luke did something most unexpected.

‘I love you,’ he said, nudging his forehead against mine. ‘Thank you.’

Love wasn’t something we mentioned often. There didn’t seem to be any need. Luke and I were a pair—we fitted. I don’t think either of us felt quite complete without the other. Why go on about it? Only teenagers and film stars talk about lerve.

‘You’re very welcome,’ I said, smoothing his hair. I liked the way it lay over his ears, blue-black and tinged with silver, like a bird’s wing. ‘I’ve no idea what I’m being thanked for, but I definitely deserve it.’

Something had changed. The world had grown dark. The rain intensified in a sudden roar, louder than machine-gun fire, and the stream was a mud-brown torrent. Luke was in the water. It was sweeping him away. I grabbed an old tyre from the mud and tried to throw it to him, but he didn’t reach for it. I screamed at him to swim, swim, but he didn’t. His dark eyes looked straight past me as water poured down his face. He seemed to see something beyond. The next moment I’d been sucked in too. I was drowning. I was shouting for Luke, but he was gone.

Panic woke me, thank God. The blanket was bundled around my face. I threw it off, yelling because I’d lost Luke in the river. Casino was on his feet, bottlebrush-tailed.

‘Horrible, horrible,’ I gasped, reaching out to touch his warm fur. ‘Horrible dream.’

For some minutes I felt breathless, winded by the gallop of my heartbeat. Then the old cat began to lick himself, and eventually he lay down again. His calm was comforting. Above my head, the square patch of sky had lightened to a pale grey. Luke would be up by now. Perhaps he was already heading into the office, to face five hundred emails.

‘Pop downstairs and make me a nice pot of tea, will you, Casino?’ I asked, but the little tabby just curled a paw across his face. I stroked his head. ‘Too early for you? Yes, well. It is bloody early. It’s—hang on, is that a car?’

Casino and I both pricked up our ears at the crunch of wheels on gravel. I rolled out of bed, pulling on my dressing-gown as I peered out into the rain-streaked morning. Who on earth would turn up at this ungodly hour? I imagined the police, with bad news and solemn faces. I expected to see a panda car parked in our drive.

A moment later I’d charged downstairs and thrown open the front door with a shout of welcome. Luke was walking towards me through the rain, his trench coat over one arm.

‘You’re soaked,’ I scolded.

He looked down at himself. He was wearing suit trousers and his black corduroy jacket. His hair was plastered to his head, and droplets trickled under his collar. He seemed lost, but that wasn’t unusual for him. It was one of the things that had struck me about him on the night we met; that, and the strong feeling that I’d known him all my life.

I put my arms around his neck and kissed him on the mouth. ‘Wet or dry, I am very, very glad to see you! So you changed your mind about going into work? Well, what a lovely surprise! You’d better have a hot shower.’ I led him inside and shut the door on the rain. ‘Coffee or tea?’

Casino had heard all the commotion. He lolloped down the spiral staircase, made a beeline for Luke and arched against his legs. He was meant to be the children’s cat, but Luke was his idol.

‘He’s a one-man cat,’ I said, taking two coffee cups down from the dresser. They were handmade, painted in red and yellow and with matching saucers. Relief was making me chatty. The cold clutching in my stomach—the drowning nightmare—had meant nothing, after all. I rambled on about the weather and the garden, and Kate and Owen. Luke stood watching me, dripping rainwater onto the tiles.

‘Chop-chop,’ I nagged, pushing him towards the stairs. ‘You’ll catch your death. How come you set out so early?’

‘I lost the keys to the flat.’

I gaped. ‘Sorry? Don’t you have a spare set?’

‘They’re here. So I went to Paddington and waited for the first train.’

It didn’t make sense. ‘But . . . you’ve surely not been sitting in Paddington station all night?’

‘No, not sitting. I walked around.’

‘All night, in the storm? Why didn’t you just go to Simon and Carmela’s place? They’d have put you up. For heaven’s sake—you could have phoned me. I’d have driven in. You know I would.’

‘Yes, I know that.’ He seemed to retreat into the hollows of his eyes. I watched him, and that aching chill returned. I’d seen him like this before. It was as though he were being tortured: silently, privately.

‘What were you thinking, as you walked all night?’ I asked.

He didn’t answer.

‘Darling man.’ Sliding around the edge of the island, I touched his face with the palms of my hands, turning it to face mine. ‘Is it back? You know these low times always pass. Why on earth didn’t you phone me?’

‘I was making a choice,’ he said. ‘I have made it. And now I have to tell you something.’

The room faded away. There was only Luke, ghost-faced and soaking wet. I remembered the day my father turned up here—standing pretty much where Luke was now—and told me they’d found a shadow on his lung. I’d wanted to weep at the determined optimism in his voice: It’s not a one-way ticket nowadays, the Big C. They can do amazing things with chemo. Six months later, we buried him. My mother didn’t even come to the funeral. Death’s powerful, but it couldn’t dent her bitterness—though why she’d been bitter when it was she who ran off with somebody else, I never understood. She outlived Dad by ten years before the Big C got her, too.

‘Are you ill?’ I asked now.

‘No.’ Luke gave a sniff of laughter. Well, not really laughter. ‘Sick, perhaps. Yes. People will certainly say I’m sick.’

I breathed again. Not cancer, then. Not some other terminal illness. Anything else could be borne. ‘Are you having an affair?’

‘No. No! I’d never . . . there’s never been anyone but you.’

I had no idea what was coming. I really thought it was something quite trivial. Perhaps he’d lost his shirt in some dodgy investment? Well, so be it. Money isn’t the most important thing in life.

‘Sit down,’ I said, as I carried our coffee to the table. ‘Tell me what’s going on. A problem shared . . .’

It’s seen some action, our kitchen table. For over a quarter of a century, our lives have revolved around its blue-painted legs and scrubbed oak top. It’s seen children’s baptisms and birthday parties; it’s hosted flaming family rows and teenage revels and endless games of Monopoly. Its face bears the honourable scars of hot saucepans, Kate’s henna, and Simon’s early attempts at soldering. It knows us all, very well.

Luke didn’t sit down. ‘You’ll be revolted,’ he said.

‘Try me! Whatever it is can’t be so terrible, if you aren’t ill and you’re not having an affair. Is it financial? Have you lost our pension? Our house?’

‘No.’

‘Has Bannermans gone bust?’

‘No. No.’ He held out his hands, palms downward, as though trying to suppress my guesses. ‘It’s who I am. I have to tell you who I am.’

‘You look like Luke Livingstone to me.’

‘Yes, I look like him. But I’m not.’

‘I think you’ll find you are.’ I was forcing a smile.

‘I’ve been running from this all my life. I can’t run any further, Eilish.’

And then he began to talk; but it was as though he were speaking in some foreign language because I could get no sense from his words. He kept saying that he was not who I thought he was, he had never been who I thought he was; that he wasn’t unique, that there were others. You must have noticed, he kept saying. You must have suspected. Suspected what? I wondered, my mind racing in terror. Noticed what? Luke was a rational man—sensitive, occasionally depressed, but above all rational. Perhaps he’s had a bang on the head. Or—dear God, maybe he’s had a stroke? Brain tumour? Must get him to a doctor, right away.

‘Stop,’ I snapped. ‘You’ve been talking for ten minutes and I still have no idea what you’re trying to say. You seem disorientated. I think I should drive you straight to the hospital.’ As I talked I was hurrying around, looking for my bag, fetching my car keys from their hook beside the fridge.

‘I think I was meant to be a woman,’ he said.

‘They might keep you in for tests. You’ll need warm, dry clothes. I’ll go up and—’

‘Eilish, listen. Please listen.’ Something in his tone made me stop and turn around. He’d pressed a hand across his eyes. ‘I look like a man called Luke. I’m imprisoned inside the body of a man called Luke. But I am not him.’

I didn’t want to understand. I was afraid to understand. ‘Okay,’ I said, ‘just stay calm. Are you in any pain?’

‘Eilish.’

‘An ambulance might be faster.’

‘I’m not ill.’ He sat down heavily, as though his legs wouldn’t take his weight any longer. ‘There’s a name for it.’

‘Don’t say any more,’ I begged him. ‘Let’s just—’

He spoke over me, so loudly that I couldn’t ignore him. ‘It’s called gender identity disorder.’

Gender identity disorder. I’d heard the term. A couple of years before, at a teachers’ conference, I’d attended a seminar on the subject. We spent an entire day learning about boys who wanted to dress, play and be treated as girls; and about girls who longed to be male. Some had help from a clinic—even took hormones, which shocked me. There was lots of trendy discussion about which toilets they should use; one of the people on the course had been in a legal dispute with some parents because the school wouldn’t let their boy dress in a skirt and call himself Tanya. I like to think of myself as open-minded, but I didn’t really get it. Poor tormented things, I thought. I even—very secretly—suspected that the parents might be to blame.

And as for adults? Well. We’ve all seen those strange creatures, men with wigs and handbags, lurching along on high heels: the wrong shape, the wrong voice, and always alone. I pitied them—actually, when I was young and cruel I laughed at them—but they had nothing to do with me. They were from another world altogether.

‘Enough,’ I said now. ‘This isn’t funny. You aren’t a . . . That’s got nothing to do with you.’

‘It has everything to do with me.’

‘No, darling, it hasn’t.’ I wanted to talk sense into him, as though he were one of my pupils. I sat down next to him. ‘That’s for children who are still finding their way, their sexuality, maybe trying to please parents who always wanted a boy or a girl. They’re just very, very confused young people. It’s got nothing to do with middle-aged solicitors with wives and families.’

‘I’m female. My body looks male, but I am not. It isn’t new, Eilish, I’ve felt this all my life. I was born with the wrong body.’

He might as well have announced that he was an alien from some far-off galaxy, inhabiting the body of a human. I knew it wasn’t true. I didn’t know why he was putting on this charade, but I knew it wasn’t true.

‘I know you,’ I insisted, with a panicky little laugh. ‘I know exactly who you are! You’re a man. You’re my man. This is crazy.’ I’ll wake up in a minute, I thought. I tried to shake myself out of sleep, but it didn’t work. ‘You expect me to believe that you’ve felt . . . been hiding . . . this . . . what, since the day we met? You wouldn’t do that to me. I know you wouldn’t. I know you. You’re Luke.’

He put his face in his hands. Casino jumped onto his lap and began to knead.

‘I’ve got to explain,’ Luke said. ‘Please let me try.’

I was too stunned to interrupt as he described how he had always thought of himself as female, even when he was a little boy. He said again and again how sorry he was; he would understand if I divorced him, but he could no longer keep up the pretence that he was a normal man. He said he didn’t want to lie anymore. He said that he loved me.

I sat and listened without comprehending, and thought about how he’d walked all night in the storm. A nail had begun to work its way out of my chair. Quite deliberately, I pressed my shoulderblade against its sharp tip. The pain was at least real and tangible in that nightmare fog. The world was tipping, and I was going to fall off. Water began hosing against the windows. Spouting’s buggered again, I thought, as though it mattered about the bloody spouting.

‘Do you mean you’re gay?’ I asked suddenly. ‘Is that what this is all about—you want to sleep with men? You’ve never really wanted me at all?’

‘No. I’m not gay. That would be so much easier.’

I laughed, because it was absurd. ‘Easier?’

‘Less complicated.’

‘So . . . what does it mean? I don’t understand what this means. Are you leaving me?’

My question was still hanging above our heads when the phone rang. It seemed irrelevant. Through the mist, I heard Simon’s voice on the answering machine. Poor Simon. He sounded cheerful. He thought his world was still whole.

‘Hi, Dad. Hi, Mum. Um . . . I expect you’re still asleep, sorry if I’ve woken you up. Dad, just wondered if you caught the interview on Radio Four just now, about mediation across cultures? Pretty interesting, thought you might . . . er, anyway. You can always listen to it online. Hilarious, what they say about non-verbal communication with Norwegians. Um, Carmela sends her love. She’s fine—tired, obviously, but blooming. We’ll see you both tomorrow, if we’re still coming for lunch? I thought I’d check that’s still on, but I’ll assume it is unless I hear from you. Hang on . . . Nico wants to say hello.’

A pause. Whispers. Heavy breathing. Then the careful tones of a four-year-old who’s been allowed the adult privilege of talking into the telephone.

‘Hello, Grandpa . . . Hello. Hello? . . . He’s not there, Dad.’ There were more whispers before our darling grandson spoke again. This time he used his formal message-leaving voice. ‘Hello, Grandpa and Granny. It’s fish for breakfast. I have a new baby bruvver or sister coming. When are we going to make the wooden plane? Bye.’

I pictured Nico crashing down the receiver before racing back to his fish-for-breakfast. Then there was silence in our kitchen. Water gushed against the glass.

‘Are you going to leave me?’ I asked again.

‘I think that’s up to you. All I know is that I have to change. I can’t go on pretending to be something I’m not.’

Then I remembered something I’d read once, in a magazine at the hairdresser’s, about a woman who found her husband’s stash of women’s clothes. It turned out he wore them often, as soon as her back was turned. It was the worst day of my life, she said. I read it with prurient interest while they did my foils. The husband had announced that he wanted to be female. There was a picture of two women, and one of them looked downright odd.

‘You’re married,’ I said now, with an obstinacy born of terror. ‘You have children and grandchildren. You are Luke Livingstone, for heaven’s sake! Luke Livingstone—who is very male indeed, I can assure you, and I damn well ought to know because you’ve shared my bed for three decades, and we’ve had three children in that time.’

‘I’ve tried to be.’

‘No . . .’ I was desperately trying to think, trying to make him see how insane this was. ‘You are my friend, my lover, my husband. I would have known.’

‘I hoped you did know, in some way.’

Memories were imps, their grinning faces forcing cracks in my denial: Luke dressing for a tarts and vicars party, wearing my shortest skirt and putting on make-up with surprising skill. He was the life and soul of the party that day, flamboyant and loud, as though the costume freed him from his usual reticence. Nice legs! people yelled across the room, as he danced with our hostess. You’d make a hell of a babe, Luke.

‘We’re so happy,’ I said. ‘Aren’t we? Why tell me this now?’

‘Because I’ve come to the end of my road, Eilish. The very end. I can’t go on. I was facing a choice last night: to end my life, or to accept what I’ve always really been. I am so sorry.’

The nail pierced my back, holding me upright. If I’d been less stunned I might have asked him what he thought would happen next; I might have asked about practicalities—what exactly had he chosen? But such questions were far, far beyond me.