6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

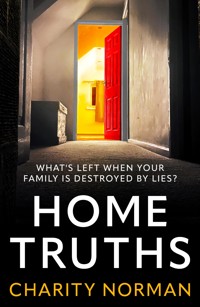

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

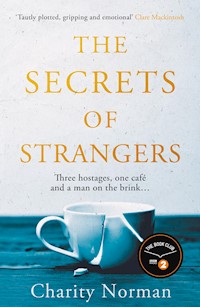

From the authr of Richard and Judy Book Club pick After The Fall comes a gripping and moving novel, perfect if you love books by Jodi Picoult. 'Tautly plotted, gripping and emotional' - Clare Mackintosh, bestselling author of After the End A regular weekday morning veers drastically off-course for a group of strangers whose paths cross in a London café - their lives never to be the same again when an apparently crazed gunman holds them hostage. But there is more to the situation than first meets the eye and as the captives grapple with their own inner demons, the line between right and wrong starts to blur. Will the secrets they keep stop them from escaping with their lives? Shortlisted for 'best novel' in the 2021 Ngaio Marsh Awards

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

CHARITY NORMAN was born in Uganda and brought up in successive draughty vicarages in Yorkshire and Birmingham. After several years’ travel she became a barrister, specialising in crime and family law in the north-east of England. Also a mediator and telephone crisis line listener, she’s passionate about the power of communication to slice through the knots. In 2002, realising that her three children had barely met her, she took a break from the law and moved with her family to New Zealand. Her first novel, Freeing Grace, was published in 2010. After the Fall was a Richard and Judy Book Club choice and World Book Night title. See You in September, her last book, was shortlisted for Best Crime Novel in the 2018 Ngaio Marsh Awards for Crime Fiction. The Secrets of Strangers is her sixth book.

First published in Australia and New Zealand in 2020 by Allen & Unwin

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Copyright © 2020 by Charity Norman

The moral right of Charity Norman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders.

The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Fax: 020 7430 0916

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this bookis available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 91163 041 8

E-Book ISBN: 978 1 76087 200 7

Printed in

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Barnaby Norman

(Pluffy)

1998–2018

‘I shall not look upon his like again.’

William Shakespeare, Hamlet

ONE

Neil

It’s the rattle of coins dropping into his cup that wakes him. That, and his friend the one-legged pigeon with his happy-bird crooning. That, and the stream of arctic air invading his sleeping bag. That, and the whole bench shuddering as a bus wheezes down the High Road.

Thirty seconds ago he was comfy in his old bed, his arms around Heather, his nose in her hair. Shampoo and laundry powder. But there must have been a door open somewhere because ice was seeping in. He’d have to get up and shut that bloody thing. Anyway—dammit—he needed a pee.

Then the clatter in his tin mug. Heather’s beautiful warmth is going, going, gone as reality pours back in all its disastrous glory. Mind you, it’s a relief to wake up at all. Always good to know you’ve made it through another night. He opens his eyes just in time to register the squeak of rubber soles and glimpse a sturdy silhouette marching off across the church car park. Buddy pokes his head out from his blanket, ears pricked, sniffing.

There’s four quid in the cup: a lucky birthday present from someone who doesn’t even know it’s his birthday. Many happyreturns, you useless sod. He mouths it, not quite aloud. Tries not to talk to himself. Losing battle. Soon he’ll be one of those shambolic wrecks who mutter and curse under their breaths, the kind he used to feel sorry for. To be honest, he doesn’t want many returns of this kind of day.

Buddy heaves a sigh, and his greying muzzle sinks back onto his paws. He’s old. He just wants to sleep. Neil watches the one-legged pigeon pecking at a hefty crust of bread. His bladder’s becoming insistent but he’s putting off the moment when he has to face the cold and find out the hard way which bit of him aches the most. His dodgy knee. Maybe his creaking hip. Maybe his back.

He lowers his feet to the ground just as a pair of fire engines come bellowing past, sirens dropping and slowing. Doppler effect. He used to teach kids about that. He even had a video clip of a passing ambulance he used to play in the classroom, once upon a time when he was a clean-shaven know-all with a family and friends and a home and a sofa to sit on at night to watch telly.

His daily routines are different these days: rolling the sleeping bag and Buddy’s blanket with raw fingers, folding the cardboard box he uses as a mattress, shoving everything into his trusty backpack. It’s been on Duke of Edinburgh tramps, this pack. He’s carried it all over Exmoor with sixth-formers hanging on his every word. Mr Cunningham, the fount of all knowledge—how are the mighty fallen! The pack’s decrepit now, straps broken, open-mouthed tears all along the seams, more hole than it is nylon. He’s done his best to plug the gaps with plastic bags but the end is surely nigh for his old friend.

Jeepers, this wind. Might as well be in bloody Siberia. He’s wearing the warmest clothes he’s ever owned: gloves, anorak and what’s left of his blue-and-red bobble cap. He never takes it off in winter. Sleeps in his boots too. It’s safer. He keeps everything else he owns in three plastic shopping bags. These, along with the backpack, he stashes under the hedge at the church’s boundary, getting down on hands and knees to push them out of sight. His worldly goods blend in. They look like all the other rubbish.

Foxes live under this hedge. It’s one of the few joys of rough sleeping, watching those wild creatures up close and personal under the sickly streetlights. He feeds them when he can. Buddy’s stopped growling at them, and one of the vixens is getting bold. He’s almost touched her.

He has a pitch selling the Big Issue outside Sainsbury’s but his slot doesn’t start until the afternoon rush hour. Sometimes he whiles away a few hours in the bookie, or sneaks into the library to read newspapers. Often he has to beg if he wants to eat. Not today. Four pounds in his cup, another three-and-a-bit in his pocket. Seven quid. Luxury. By rights he ought to put the whole lot on Westerly Boy in the first race at Haydock. He’s got a very good feeling about Westerly Boy.

There again, the bookie won’t be open until eight o’clock, and Neil’s shivering now. His stomach is gnawing itself. Hunger hurts. Cold hurts. Everything hurts. He’d murder for a cup of tea and a bit of human company, and Tuckbox do giant mugs for one pound eighty. They’ve got big radiators, a toilet with fluffy towels, even a bowl of water outside for dogs. Last week the barista gave him some leftover pies. Buddy and he and the foxes shared them.

‘Tuckbox it is, then,’ he says, passing a frayed piece of string under the dog’s collar. ‘C’mon, Buddy.’

The streetlights are still glowing along Balham High Road, orange halos in the murk. A rind of ice coats the gutters. Skeins of hurrying commuters flow around him as though he’s a slow-moving branch in their river. Some are smoking, some talking nonsense into phones, their shiny shoes crunching in the grit. Buddy’s a good scavenger. He finds half a burger by the side of the road and scoffs the lot without changing pace.

Neil begins to whistle quietly. He’s picturing himself jammed right up close to one of those heavy old radiators in Tuckbox, a mug between his hands, tea with lots of sugar. Newspaper to read. Marvellous. And when the bookie’s shop opens he’ll get himself straight in there and keep his fingers crossed for birthday luck.

Today’s the day! The tide is on the turn, and his ship is coming in.

TWO

Abi

She felt his kiss as he crept out at six, heard his hopeful whisper—Let me know, won’t you? Even if it’s not good news?—and nodded without opening her eyes. She couldn’t bring herself to tell him. Better to wait for the phone call to make her latest failure official.

Sleep’s overrated. After all, you’re a long time dead. Charlie left a mug of coffee for her on the bedside cabinet, and it’s still hot when she hauls herself into the shower. By seven-fifteen she’s dressed, blow-dried, has sent off several urgent emails and is slamming the front door closed behind her. Turn left at the gate, head for the station, double-quick. So much to do, so little time.

Monday. Results day. That all-important piece of paper will already be on someone’s desk. For some reason, Charlie’s been extra optimistic about this round. He keeps rubbing his hands, muttering, Fifth time lucky, eh? It’s our turn, isn’t it, Abi? Poor guy. He’s going to be crushed again.

She’s due at St Albans Crown Court this morning to defend a woman accused of shaking her nine-week-old baby, causing catastrophic brain injury. The brief only arrived in Abi’s pigeonhole on Friday, after her fraud trial was adjourned. She met the mother an hour later. Kelly Bradshaw: young, gaunt, dissolving. I love Carla. I know you never ever shake a baby. It all hangs on the timing of the injury, but there’s a glimmer of hope there, because the prosecution expert doesn’t seem quite sure.

Abi speeds up, towing her case on its wheels. The next train is due in twelve minutes and she intends to be on it. She’s mentally running through the week: lists, decisions, things-to-remember—organised, compartmentalised and flagged for action. She’s planning her cross-examination of the prosecution’s neurologist. She’s conjuring excuses to avoid Christmas lunch at her parents’ place: Dad being Dad in all his dickish glory; her sister Lottie like the Madonna, beatifically breastfeeding. She’s thinking about results day.

Heartburn is raging in her solar plexus. Without breaking her stride she checks her bag, looking for antacids. Bugger, she’s out. Better get some more.

The judge in Bradshaw has zero empathy. He’s going to be a total bastard when Abi starts making last-minute applications—which she fully intends to do because the defence case is a shambles. She needs social services records, and she plans to challenge the admissibility of Kelly’s disastrous police interviews. Abi is going to be public enemy number one this morning.

She’s nipping into Boots when her phone rings. It’s early for the clinic to be calling, and it’s not from their usual number, but she feels a lurch of anxiety as she answers.

Not the clinic. It’s Henry, her instructing solicitor in today’s trial. He’s losing his cool.

‘Slight problem,’ he says. ‘The prosecution served an addendum report from their neurologist.’

‘And?’

‘It plugs the gap. He puts the time of injury squarely during the hours when Mum was alone with the baby.’

‘When did they serve this?’

Henry sounds mortified, and well he might. ‘Actually, two weeks ago. It got misfiled at our end. Luckily I came in early, I was checking the file. An intern . . .’

‘Bloody hell.’ Abi’s thinking fast as she grabs a packet of antacids from the shelf. ‘Look, can you get in touch with our expert, email him that report, try to get his response immediately? Email it to me too. I’ll read it on the train.’

‘Okay.’

‘I should be with you by nine.’

The self-service tills aren’t working. She and two other customers have to wait for a guy to amble across, chewing the cud. Bloody hell, would he hurry up? Seconds tick by and are lost forever—time, the most valuable commodity in her life. She can feel drips of acid burning her oesophagus as she finds Tuckbox Café on her phone and texts in her order. They don’t faff about. That’s why she’s so loyal to the place. It takes Sofia, the barista, an average of ninety seconds to exchange staccato pleasantries and produce an espresso-to-go.

She’s out. Six minutes to the train. Three dogs are waiting on the pavement outside Tuckbox, their leads attached to bike racks. A rangy old boy sits a little apart from the others with his ears pressed forwards, gaze fixed on the door, obviously determined not to move until his human reappears. His lead consists of a piece of blue twine. The other two know Abi and are tail-waggingly delighted to see her.

‘Hi, gals,’ she mutters, patting them as she passes by. Dixie and Bella: an anorexic greyhound and a creamy teddy bear, both dolled up in twee tartan coats. Abi’s got a soft spot for these two, although she avoids their owners like the plague. Renata, Rory and their twin baby boys live next door, at number 96. Their smugness knows no bounds.

Fifty per cent chance, the quacks say. Fifty per cent. Seemed like reasonable odds the first time, even the second. Don’t seem so good now that she and Charlie are enduring their fifth round, rapidly using up their precious frozen embryos, their savings, their hope. It’s an endless marathon: running and running, hearts and lungs screaming while the finishing line keeps moving further away. Yet all this time they’ve been brazening it out. They commute, they work, they laugh, they go to other people’s children’s christenings, they redecorate their home, they radiate success and control, they feverishly pretend their childlessness is a lifestyle choice. They watch one another grieve.

The clinic will be calling this morning, probably at about eight. She knows the drill. She also knows exactly what they’re going to tell her and she doesn’t want to hear it.

She reaches for the door of Tuckbox Café. Five minutes to the train.

THREE

Mutesi

Mrs Dulcie Brown died in the early hours of the morning. She drifted over the bar from sleep to death, no fuss or fanfare, her heart finally still after almost a hundred years of life. Three in the morning is a popular departure time from the Prince Albert wing: the peaceful hour, when night staff move quietly through their routines and the cooks haven’t yet begun to clatter.

Her family began to arrive just after the doctor who certified the death. Mutesi brought them a tray with tea and biscuits. She found them chuckling over their memories, making up for all those years when memory was lost. Mrs Brown had been absent for a decade, wandering through that homesick hinterland where all faces look alike and nowhere is home, clinging to a stubborn straw of dignity. Mutesi had pinned photos up in her bedroom as a reminder of who this shadow really was: Dulcie Agnes Brown. Mother, grandmother, great-grandmother. A Land Girl in the war, a magistrate. A tiny girl in a white dress and socks, staring solemnly out at her descendants.

Mutesi’s shift ends at six, though she lingers to write up her notes before stepping out of the tropical heat of the nursing home into an icy pre-dawn. She catches the bus to Balham, lumbering across the frosty savannah of Tooting Common before hopping off at the stop beside St Jude’s church. It’s still dark—at least, the air glows in that constant twilight that passes for dark in London—but the city is already awake. You can hear it; you can feel it. Mutesi loves the sense that a giant is stirring and opening its eyes.

The homeless man is sleeping on the bench again. She can just make out his bobble cap and his dog’s white-speckled muzzle peeking out from under a ragged blanket, both of them looking far too old for this kind of life. A tin mug sits on the ground nearby. Perhaps he’s left it there in hope of donations, or maybe it’s his bedside cup of water. After all, why wouldn’t homeless people have bedside cups of water like everyone else?

The bench is a popular spot for rough sleepers. It’s set into an alcove in the church wall, sheltered from the worst of the weather. There was a fuss about it at the last parish council meeting. It’s true that some of the sleepers leave bottles, cigarette butts and a pervading smell of urine behind them, but not this one. The curate offered to contact an emergency shelter for him but he’d politely refused, saying it was a revolving door and, anyway, he needed to keep his dog. Mutesi fears they’ll find the pair of them dead one day, frozen stiff in the church grounds. It can’t be right.

St Jude’s is locked up like Fort Knox, but she’s on the cleaning rota and has keys to the side door. She flicks on a minimum of lights, strolling peaceably among the frozen shadows of the nave, her footsteps startling saints in their stained-glass windows. The echoing space smells of polish and dust and plasticine from Sunday school, and now the pine of the enormous Christmas tree. Some people won’t venture in alone at night—spooky, they say, shivering. Mutesi likes it. She can certainly feel the spirits all around, but they’re kindly. Well, most of them are.

She stops under the ornate carving of the pulpit, beside the tea-light stand with its wooden box for donations, and lights a candle for Mrs Brown. This is her private ritual whenever a resident dies. After a minute has passed she lights another for all the beloved souls she lost long ago, back home. Just one small flame must represent them all: it would take all the tea-lights in the basket if she were to light one for each. She leaves the candles burning, two tiny tongues of fire in the darkness.

It’s only as she is stepping out into the dissolving night that she remembers the donation box. It’s not compulsory, but to light candles without paying feels like stealing. She has a couple of two-pound coins ready in her pocket. Ah, well, never mind. She’ll settle up on Wednesday when she goes in for choir practice.

The one-legged pigeon flutters to land at her feet. He lives on one of the gargoyles and he knows her very well. Clever bird! She rummages in her bag for her plastic sandwich box.

‘Yes, yes,’ she murmurs, tipping it upside down. ‘You’re in luck, Hoppy.’

The pigeon is already pecking as crusts cascade onto the asphalt. Yawning, Mutesi holds her watch close to her eyes. Five past seven. She’d dearly like to go home and make tea in the Grandma mug Emmanuel gave her. She longs to curl up under heavy blankets with her eyes closed. That is a luxury—drifting away while the rest of the city suffocates on trains and buses. But it’s Monday, and she has to meet Brigitte and Emmanuel at Tuckbox. Mutesi’s job is to give her grandson breakfast before walking him to school. They will share a cheese toastie and a pot of tea. He will talk and talk, and she will smile and smile. Mutesi counts her blessings every day. The blessings keep the horrors at bay.

She stoops to check the man’s tin mug is empty before sliding her coins into it. There. Her gift has been delivered straight to a place where it’s needed, with no middleman. She’s never quite sure whether this is true of the donation box.

It takes a little over ten minutes to walk along the High Road, past the GP surgery—cheeky young locum she saw last time tried to put her on a weight-loss program, as though she’s anything but healthy and fit for her age!—under the railway bridge. Fire engines scream past, scattering a queue of cars, and she spares a thought for whoever’s life is being turned upside today.

Tuckbox is another world again: humid and neon-lit, cheerfully noisy with the hiss and gurgle of the coffee machine, the rumble of conversation, music from a radio station. The front counter faces the door, with cabinets forming an L-shaped border around a busy kitchen. Customers queue at the counter, or hang about as they wait for their takeaway orders. Most seem fixated on phones or newspapers. A young man and woman stand gazing into one another’s eyes. A trio of teenagers in school uniform has just ordered. One of them sees something on her phone and holds it out to the others, who double up with laughter.

The café’s owner is polishing his glass-fronted cabinets. He’s a tall, handsome figure, always upbeat, though Mutesi knows the poor man buried his wife about a week ago. Tragic thing. Cancer, and so quick. Brave of him to be back at work already.

‘How are you today, Robert?’ she asks.

He lights up at the sight of her. ‘Keeping on keeping on,’ he says. ‘Lucky to have customers like you.’

‘You won’t take some time off?’

‘Nah. Helps to keep busy. If I think about Harriet too much I’ll turn to mush.’ He’s still smiling, but his voice is fraying. ‘The thing is, she was my life, you know? Home isn’t home without her.’

‘I know.’

‘I wake up and she’s not there.’

A timer beeps loudly in the kitchen.

‘No rest for the wicked,’ Robert mutters, and he winks at Mutesi before skidding behind the counter to take trays of golden-brown pastries out of the big oven. Next he’s helping the new runner at the back service counter. He’s a hands-on boss, always ready to pile in himself.

Mutesi orders tea and a cheese toastie before looking for a table.

Ah! Good! Emmanuel’s favourite spot in the window corner is free. She sits and waits, takes delivery of a pot of tea from a girl in a black T-shirt with TUCKBOX in white letters across the front. Snatches of conversation reach her from the booth nearby. Did one-ninety, dead lift, made it look easy . . . Apparently someone missed leg day last week and is suffering for it.

Brigitte and Emmanuel are late. Never mind. Mutesi is just taking that first heavenly sip of tea when they come scurrying in from the street. Her grandson looks smart in his green school uniform, a satchel slung across his chest. She feels her heart swell at the sight of those bright eyes, the broad forehead and sticking-out ears. His lashes flick upwards like sunbeams. She knows her survival has been worth something, because this beautiful child is the result.

At five foot nothing, Brigitte is several inches shorter than her mother-in-law. So clever, so loving—Mutesi can’t imagine anyone else who might be good enough for Isaac. Emmanuel gets his enormous eyes from her, and his white teeth and lovable grin. She’s wearing a beret over short, braided hair, her mouth muffled by a scarf. She feels the cold.

‘Late again,’ she gasps, shivering. ‘I’m so sorry.’

‘Don’t worry!’ Mutesi stretches her arms wide so that both mother and son can fit into her embrace. ‘You have a lot on your plate. And how is the handsomest and most brilliant schoolboy in the world?’

The most brilliant schoolboy has his mittened hand stuck high up in the air. The rule at his smart school is not to speak until the teacher says you may, and he’s taken to doing the same at home. It began as a game but now it’s a habit. Mutesi strongly disapproves—he is only six years old. Six! Why are they teaching him to behave like a soldier? Children should never be soldiers. Never. Never.

‘Mummy lost her phone,’ he says. ‘She rang it but the battery was flat and now she has to go straight away because she has an important meeting.’

He has plenty to say about the lost phone, the bad words Mummy used and how he heroically found it in the bathroom. Mutesi keeps her listening face on for him, but she and Brigitte are both distracted by raised voices nearby. A young fellow—wild hair, wild eyes—is yelling at the café’s owner. Why didn’t you tell me? I’ve come to get her! What the fuck have you done with her? Robert is making calm down gestures, pressing downwards with his big hands as he talks. He seems to find the whole thing quite amusing. He may be a generation older than the shouting boy, but he’s a head taller.

There’s a powerful shove to Robert’s shoulder, a final curse—fucking evil—and words that Mutesi doesn’t catch over the music and a roaring coffee grinder. The whole thing is over as suddenly as it began. The young man bangs out through the street door, briefly colliding with a woman in a dark overcoat who’s just coming in. The next moment he’s pelting past the windows.

Café life pauses. There’s a collective moment of nosiness. Then the milk frother starts up, and the smoothie blender. Someone laughs. Conversations resume. Robert’s joking with a group of women in jogging clothes, tapping the side of his head. They’re chortling. The woman who was almost knocked over is waiting at the counter, talking on her phone.

‘That man used his outside voice,’ says Emmanuel, pouting in disapproval. ‘And bad words. Uh-uh. Naughty.’

Mutesi tugs gently on his ear. ‘Maybe he didn’t like his coffee.’

‘Or he didn’t take his pills this morning,’ says Brigitte. ‘I must go. Emmanuel, you’ll read to Grandma, ask her to sign your reading diary?’

Emmanuel’s hand is back in the air.

‘I forgot my book. I think it’s in my bed.’

‘Not again!’ Brigitte rifles through his bag. ‘Miss Soames will fuss.’

‘Look who’s back,’ says Mutesi, nodding at the door.

Brigitte is too vexed to look up from her search. ‘It’s been a crazy weekend. Isaac’s flight to Montreal was delayed and—’

Her sentence ends in a shriek as Mutesi hurls herself at both mother and son, shielding them with her own body.

‘Get down,’ she says. ‘On the floor. Now.’

FOUR

Abi

Her hand is on the door of the café when it swings towards her and someone comes thundering out.

‘Sorry,’ she mutters instinctively, stepping back as he barges past without so much as a glance in her direction. Charming. She has a fleeting impression of furious energy. Curly hair, heavy eyebrows. Grey cable-knit sweater and jeans. Not at all bad-looking, actually—hot, her vacuous sister Lottie would say—but seriously short on manners. He’s obviously in a hurry. Well, fair enough. So is she.

Tuckbox smells of coffee and toast, and it’s heaving this morning. The place aims for functionality alongside shabby comfort: a brushed cement floor, crimson walls, black-and-white photographs of sweeping landscapes, newspapers scattered around. Customers can choose between wooden tables, retro-style booths with red vinyl seats or worn leather armchairs grouped near the front window. Abi immediately notices a heavily pregnant woman making camp with a toddler and an elderly man. The young mother’s in maternity jeans and fleece-lined boots, sporting a Baby on Board badge. Go on, Ms Fertile, rub it in. The little girl has white hair tied like a miniature fountain. Spindly legs in woollen tights stick straight out as she perches on her chair. She’s pretending to spoon-feed a toy Roo, opening and closing her own mouth while scolding the baby kangaroo in a bossy imitation of a grown-up. Abi watches, enchanted despite her jealousy, aching with the absence of someone who has never existed. She forces herself to look away, only to spot Renata from number 96 and her posse of yummy jogging mates. Dear Lord, was there no escape?

The barista catches her eye and taps an espresso cup to show she’s already on to it. Funny how matey you can become with someone you meet for only ninety seconds every day. It generates a kind of intimacy. Sofia is from Italy but she has a Romanian boyfriend. She’s here first thing in the morning, often locks up at night. She’ll do anything for her employer. Customers can be such jerks, but Robert’s a great boss, she once said. Treats us all like family.

Right now, the man in question is delivering coffee to Renata and the yummies. He’s in pretty good shape for an older guy: strong jawline, waves of dark hair with a frosting of silver, and he does this eye-crinkling thing when he smiles. He’s dressed as always in an open-necked shirt. Renata is flirting openly with him, throwing her head back as she laughs. Despite being the mother of four-year-old twins she has the body of a teenager, which perhaps explains her choice of lycra for early-morning jogs on Tooting Common.

Abi’s phone is ringing again. Might be the clinic.

No, not the clinic. Charlie.

‘Charlie! What’s up? I’m in Tuckbox, just about to grab my coffee. Bit short of time.’

‘Of course you are. It’s your default setting. Sorry, I can’t stop thinking . . . Have you heard anything yet?’

He sounds so very hopeful, just as she was until she did that bloody test last night. He’s on tenterhooks, and he’s going to be broken-hearted. She wishes she could spend today with him.

‘It’s only seven-thirty,’ she says. ‘Give ’em a chance.’

‘Let me know when you hear, won’t you? Whatever the news?’

‘You could call them yourself if you like.’

She’s watching the coffee machine, mesmerised by dark liquid spilling into a cup. She doesn’t have time right now for either his hope or his disappointment. She doesn’t even have time for her own. She doesn’t have time for agonising discussions about whether they should finally accept defeat. She hasn’t time for being hurt again. All of that can wait. She glances at her watch. Four minutes to the train. It’s enough. She’ll be into the station, up the stairs and onto the platform with a good twenty seconds to spare. She will think about Kelly Bradshaw today.

‘Um, did you do a . . . you know, a test?’ Charlie’s anxiety jabs at her across the ether. ‘I saw the empty box in the bin earlier.’

Someone’s screaming obscenities. Who the hell would be starting a riot in a café at this time of the morning? Ah. It’s the curly-headed guy. He’s back. She presses her palm over her free ear.

‘Sorry, can’t hear you—some idiot’s yelling. I’ve got to grab my coffee and run.’

‘We’ll try again if it’s negative, won’t we? Abi?’

It’s just sound. She’s stopped listening. For the first time in days—in months—in years—she isn’t even remotely thinking about either childlessness or work.

‘Fuck,’ she says. ‘He’s got a—’

The world explodes. A single report, a shock wave so shattering that her eardrums seem to burst. She’s hurling herself to the ground. As both hands jerk to cover her ears, her phone spins from her grasp.

Pandemonium. The café’s erupting like a fairground ride gone wrong: high-pitched screeches, someone screaming, It’s a bomb! People are crawling under tables while others claw their way through a panicking bottleneck at the door. A little boy crouches on the floor beside a woman in a beret. The child’s arms are curled over his head. A man in a suit actually trips over the poor kid—falls against a chair, scrambles up and legs it. Sofia has grabbed a couple of schoolgirls by their clothes and is dragging them towards the courtyard at the back, yelling for others to follow. This way! Come on, come on!

The second shot is overwhelming. For a full minute Abi can hear nothing except ocean waves. The air is opaque with gunpowder and fear.

She meets all kinds of second-hand violence in her work: endless lurid photographs of wounds, bloodstains and bodies in mortuaries. She’s heard witnesses describing attacks, pathologists discussing fatal trauma—but it’s all two steps removed. By the time it arrives in court there’s a pattern to the violence. There’s an order. It’s neatly packaged.

The real thing isn’t ordered at all. She knows this now. It’s barbaric and ugly and confused and unimaginably loud. Her first instinct is to get out of Tuckbox, her second to tell Charlie what’s happening. That’s when she misses her phone. Every contact, photo, message and diary entry is stored in that little object. It’s her handle on life. While sane people are running for their lives she’s wasting precious seconds in turning back and bending to snatch it up from the floor.

She never sees who hurtles into her. Someone heavy, someone running full tilt. The impact knocks her off balance as she stoops, sending her sprawling, her forehead knocking against the radiator with a sickening thud. The pain is immediate. Her vision swims, her knees buckle. She’s conscious, but for a moment or two her mind seems blank.

It’s all over. Tuckbox seems to have been abandoned. The radio is playing a jolly Christmas song but there are no other human voices. By contrast with the Mary Celeste eeriness inside the café, a human herd is stampeding out on the street. Pounding feet. Shouts. Leave this area now, get back, move! Car horns, a roaring engine. A motorbike mounts the pavement as it U-turns. Painfully, dizzily, she uses the radiator to support herself as she stands up. It’s okay, it’s okay. The gunman will be long gone by now. She’ll leave her contact details with the police, catch the next train, get to court, take a couple of ibuprofen and begin the Bradshaw trial.

As she turns to leave, she realises her mistake. The gunman is still here. He’s about six feet away from her, pacing in manic circles with a shotgun in one clenched fist. Tuckbox looks like a battleground. Abandoned bags, coats and pushchairs lie scattered haphazardly between the tables. A mountain buggy has somehow ended up on its side. The pregnant mother, elderly man and toddler are all trying to hide under one small table. The schoolboy is clinging to the woman in the beret. Abi hears him whisper: Mummy, is that man going to shoot us too? His mother lays her mouth on his head. She’s in tears. Shush. No, but shush.

But the really, really terrible thing is happening on the kitchen floor. The café’s owner is dying, cradled in the arms of a man in a red-and-blue bobble cap. She thinks of a painting, a Renaissance pietà with its limp body and grieving bystanders, though instead of Jesus there’s a middle-aged guy in jeans and a paisley shirt. Blood is coursing out of his neck, soaking his clothes, pooling on the shining concrete. So much blood. He seems to be staring at the ceiling through half-open eyes. It’s deeply unnerving. Dead on arrival at St George’s Hospital, the notes will say, but she suspects this man was more or less dead on arrival on the floor of Tuckbox Café.

Someone crouches over him, holding towels to his wounds while speaking into his ear. She’s past middle age, a black woman in slacks and a cardigan. She catches Abi’s eye.

‘Would you please call for an ambulance?’

Her accent is strong, but her words are clear. Abi nods, immediately tapping 999 into her keypad. The woman raises her voice, calling to the people across the café.

‘Everyone should leave now. Brigitte, please take Emmanuel away. Just go quickly. I will see you later.’

It’s good advice. Best not to hang around. Abi is almost at the street door—her balance still unsteady, phone clamped to her ear—when she finds herself face to face with the gunman. He’s standing right in her path, breathing like a wounded animal, chest and shoulders rising and falling fast. His gaze is fixed on her face as though he has something vital to tell her.

‘I think I’ve killed Robert. I think I’ve killed . . . Jesus, have I killed Robert?’

‘He’ll be fine,’ she lies.

She’s racking her brains to come up with a strategy. She’s met plenty of off-the-wall guys in her work, but none of them were carrying loaded shotguns. All she can come up with is an article she once read in a magazine in the fertility clinic: ‘What to Do if You’re Hiking in the Wilderness and Meet a Bear’. You keep absolutely still, apparently. Don’t run. Don’t shout. On no account must you panic. Speak calmly and reassuringly (what is reassuring to a bear, for God’s sake?). Back away, keeping your eyes on the animal at all times.

‘Look,’ she says, ‘this has nothing to do with me or any of these people. Just move away from the door and we’ll all be on our way.’

The emergency operator’s voice is loud, clear and penetrating.

Emergency. Which service do you require?

The crazy guy seems horrified by the voice. He’s shouting incoherently, and he’s a blur of action—breaking open the gun, shoving in cartridges from his pocket, slamming it shut again, all in a couple of seconds. In the same movement he’s taken aim at Abi’s phone. It’s his sheer competence that appals her. She’s pretty sure he could have reloaded with his eyes closed. A whimper of dismay ripples from the people behind her.

Emergency. Which service do you require?

Until this moment her own mortality has seemed the least of her problems. It’s a mythological thing; a bit of a bugger, but it won’t matter until she’s too old to care. Now death has her in its sights, at close range, down a side-by-side pair of murderous barrels. Mortality is real. She loosens her fingers, letting the phone clatter to the floor.

‘It’s fine. It’s okay,’ she whispers, despising herself for the facile words. There’s nothing remotely okay or fine about this situation. She’s backing towards the counter, keeping her eyes on the bear.

The emergency operator isn’t giving up.

Are you there, caller? Hello, caller?

A flash bursts from the barrel, another appalling blast of sound. Splinters of her beloved phone fly across the concrete. She dives behind the shelter of the front counter, close to where Robert is sprawled across bobble-cap man. The gunman is still yelling though she can’t make out any words. Perhaps his voice can’t ever be loud enough to express whatever hell is raging in his head.

In the chaos, a phone begins to ring from the overturned pushchair. As if on cue, another starts up on one of the tables. Both are calling out at once, in a shrill chorus. Perhaps customers who escaped are looking for one another; perhaps the news is already out, and people are calling their loved ones to check they’re okay.

The gunman grabs both phones, drops them onto the floor and brings his boot down hard, crushing them.

‘Any more?’ he bellows. ‘Over here. All of them, over here.’

Nobody’s prepared to argue. Phones are obediently slid to him across the floor, and his solid boot stamps the life from every one of them: smash, smash, smash.

He’s a total screaming maniac, thinks Abi. He could kill any one of us, any time. He probably will.

She inches further under cover until she feels something touch her calf. Her fumbling fingers find a shoe, then a leg—a dead man’s leg. And the warm stickiness—she holds up her hand to her face, and instantly feels revulsion—is a dead man’s blood. She recognises the butcher’s shop smell. A glinting trickle is nosing its way across the floor towards a central drain. It looks like a living thing.

In this moment of nightmare, there’s a new sound—faint at first, but rapidly swelling. It’s intensely familiar, something every Londoner hears through the day and night, but right now it has an almost miraculous significance. Sirens howling, their tones intertwining, fading and reappearing. The cacophony seems to come from all directions at once. Sanity is on its way, pelting through the streets with blaring horns and flashing lights.

‘Music to my ears,’ mutters the man in the bobble cap.

The sirens electrify the gunman. His free hand goes to his head, clutching a handful of hair. He spins in a complete circle before rushing to the front windows where he pulls down all the blinds. He does the same to the street door, locking and bolting it before tugging the blinds over its four panes of glass. Working one-handed, still gripping his shotgun, he drags three heavy wooden tables in front of the door, tipping them over as makeshift barricades.

The wailing sirens reach their peak. Blue lights pulse through the blinds, rippling across his face.

The sheriff’s here, thinks Abi. Thank God. Everything’s going to be all right.

FIVE

Sam

Nothing is going to be all right. Nothing, ever again.

Lights are flashing through the curtains, making a blue river on his bedroom ceiling. Why are there lights in the middle of the night?

Someone’s shrieking. It sounds like Mum, but she never shouts. The voices of strangers: Up here, is he? Heavy footsteps, thud, thud, on the stairs, past his bedroom door. An army has invaded his safe world. Now there are people in his parents’ room. Angus, can you hear me? Angus? Angus?

He’s lying like a puppet under the dinosaur duvet with his arms and legs stiff and straight and his eyes wide open and he mustn’t blink, I mustn’t blink, mustn’t blink. It’s hard for him to keep still, but if he doesn’t move even once, everything might be all right. If something terrible happens it will be his fault for blinking.

•

Everything had been fine just a few hours ago. Summertime. Haymaking. The weather forecast said it was going to be raining cats and dogs later in the week, and the mower had broken down again. Dad was worried, working late into the night to fix it before the rain came. He’d tried phoning all the local contractors but they were up to their ears.

So there Sam and his dad were, in the tractor shed. Dad was wearing his blue overalls, a smudge of oil on his nose and stalks of hay in his hair. He was drinking coffee from a mug, though it had gone cold and husks were floating on the surface. Sam was in charge of the red metal toolbox. He knew what everything in that box was for. He was eight years old, and an apprentice farmer.

‘You’re falling asleep, Sammy,’ said Dad, smiling as Sam handed him a spanner. ‘Better hit the sack. You’ve got school tomorrow.’

‘School. Yeuch.’

‘I know. Yeuch.’

‘I’ll stay till we’ve got this fixed.’

‘We’ve done it, son! We’ve saved the day.’

Sam wanted to stay there forever. He loved working with his dad more than anything in the world.

‘Why do I have to go to school?’

‘Bit young to be a dropout.’

‘I’m going to be a farmer. I can learn everything I need from you and Mum.’

Dad thought about this. He liked to think before he spoke. He was careful with words.

‘First,’ he said, ‘you can’t be sure what you want to do with your life until you’ve tried a few things. Keep your options open. And, second, you need a good education to run this farm, or any farm. As the world changes—and it’s changing pretty fast nowadays—you’re going to need your education more and more.’

‘No, I’m not,’ Sam declared, folding his arms. ‘I’ll help you all day.’

‘Aw, Sam, I wish you could. But, hey, good news! The summer holidays are coming. They go on forever. We’ll have ages, son. Weeks and weeks.’

At the open doors of the barn, Sam paused to glance back. Dad was kneeling in the pool of light thrown by the powerful lamps they’d set up. Moths spun in the light. Bouncer and Snoops were sprawling on hessian sacks nearby. Bouncer was the old dog, Snoops not much more than a puppy. The glare made Dad’s face look white and his nose bigger than it really was. He held up a ratchet, saluting.

‘I’ll just throw it all back together. Be in soon.’

‘Okay.’ Sam lingered for one last moment. ‘Night, Dad.’

‘Night, son.’

SIX

Eliza

She hears it first from the radio in the shower: an incident in progress near Balham station. Reports of gunshots and hostages, at least one witness talking about a suicide bomber. Both tube and railway stations are out of action. All streets within five hundred yards have been closed off with resultant traffic chaos. Local businesses are in lockdown; four schools have been closed. There’s no statement yet from the police but a deluge of public speculation that this is yet another terrorist attack.

Not an off-duty day after all, then. She’ll hear from the coordinator within minutes, and Richard’s going to milk the situation for all it’s worth. Before the news is over she’s dressed and hauling her negotiation kit out of the cupboard: a blue sports bag stocked with an assortment of oddments. Painkillers, clothes, an empty water bottle, binoculars, torch, spare phone, charger, USB stick, peppermints, teabags, sachets of ready-mixed coffee.

Liam’s still bashing away on the piano downstairs, mangling ‘The Entertainer’. She imagines her son’s unsmiling face, his head bent close to the keys. He’s repeating the same phrase again and again and . . . she pauses, halfway through the act of zipping up her boots . . . yep. Again. Poor Liam. It’s the school talent quest today. He’s longing to show his classmates he’s good at something. He just wants to have a friend or two—not much to ask, is it? But Liam isn’t like other thirteen-year-olds. He doesn’t seem to be on their wavelength, doesn’t understand the rules of their social games. When they invite one another to their houses, he’s never on the list. And the awful thing is, he cares.

The news ends with another mention of the incident in Balham. People in South London have started declaring themselves safe on Facebook. By the time Eliza reaches the kitchen her phone is pinging with notifications—X has declared himself safe, Y has declared herself safe—as though all their friends are frantic with worry.

Richard’s still pretending he can’t remember behaving like an arse on Saturday night. He spent yesterday clutching his head, knocking back painkillers and feigning amnesia. Did I say that? No, I wouldn’t have said that. An apology would be nice. He still looks haggard this morning but he’s acting all jolly, yelling encouragement through the hatch to Liam. Meanwhile, the baby lounges in his highchair, ferrying yoghurt from bowl to mouth but mostly missing the target. From time to time he carefully drops a dollop over the edge, watching as it lands on Yoda the cat.

‘This thing at Balham station a job for you then?’ asks Richard. ‘Got the blue bag, I see.’

‘I’m on the rota.’

‘They’re saying it could be a suicide bomber.’

‘Might be a hoax.’

Richard’s wiping yoghurt from Yoda’s head. He’s a draftsman, self-employed. Often not employed.

‘Something always seems to happen when you’re on the rota,’ he says. ‘It’s uncanny.’

‘Sorry.’

‘Are you?’ He’s smiling, but he’s not really smiling any more than she’s really sorry.

Like all hostage and crisis negotiators in the Met, Eliza has a day job, in her case in the serious crime unit. She volunteers to be on call for negotiation during her off-duty time. It’s become more of a problem since Jack’s unexpected arrival. Everything’s become more of a problem since then.

Richard’s phone pings three times in quick succession.

‘That’ll be more drama queens declaring themselves safe.’ He takes a look, snorts. ‘Yup. See that? My own sister! She’s getting comments—Oh, hon, thank God you’re okay. Of course she’s sodding okay! She’s nowhere near Balham. Eight million people live in this city. Some of ’em are going to die today, it’s a statistical inevitability. By her logic we should all declare ourselves safe every time we get into bed at night.’

‘The Entertainer’ comes to a thumping end. There’s a blessed four-second silence before it starts again from the beginning. This time Jack joins in the concert, bashing his plastic cup against his table while bellowing Da! Da! Da!

‘I’m too old for this,’ mutters Richard. He’s wearing a fleece inside out over his pyjamas. ‘Why don’t kids have volume controls? It’s a design flaw.’

‘I see now why my father went so deaf so young.’ Eliza pours two mugs of tea.

‘The milk’s gone off.’

‘Have to be black then. Last night when I was in the supermarket with Jack, the check-out woman congratulated me on having such a beautiful grandson. Grandson! Seriously?’

‘Technically, we could easily be his grandparents. Forty-five.’

‘Do I look like a granny?’

‘No. Silly check-out lady, should’ve gone to Specsavers.’

The years have certainly been kind to Richard. Physically, anyway. He has the same straight eyebrows and tidy features that struck her the day they met, on a crowded train to Edinburgh. By York they’d swapped life stories. By Newcastle they’d swapped phone numbers. By the time the train pulled into Edinburgh Waverley their lives had changed forever. It was romantic stuff, love at first sight, a shining tale to tell the grandchildren. But seventeen years on, chips and cracks mar the glossy paintwork.

A text arrives on Eliza’s phone.

‘That’s my marching orders,’ she says, sending a rapid reply.

When she tries to give Liam a goodbye hug, he slides away along the piano stool, still playing.

‘Get off!’ he growls. ‘I’ve got to play the whole thing without a single mistake three times in a row.’

‘Remember I said I was on the rota today?’

The music stops. He glares at the keys, his back hunched in mutinous disappointment.

‘You won’t be coming to the talent quest.’ It’s a statement, not a question.

‘I will if I can.’

‘Means you won’t.’

‘I’ll do my best.’

‘Huh.’

She squats down beside him. ‘You’ll blow their socks off! Tell me all about it this evening. Okay? Okay, Liam?’

He lifts his hands high, thumps them down. He doesn’t play with panache or wit or any apparent pleasure. He plays with gritted-teeth determination. Plink-plonk.