Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

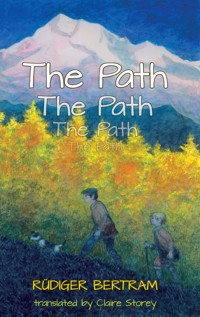

- Herausgeber: Young Dedalus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The Path is an unusual German novel for young readers as it is about World War II which is normally a taboo subject in Germany. It has been described as the story of a flight to freedom. Der Pfad has been a bestseller in Germany and made into a film in 2022. It is set in 1941 with 12-year-old Rolf, his dog Adi and his father Ludwig, who are fleeing from the Gestapo. They are in Marseille and plan to escape from France by crossing the Pyrenees with the help of their teenage guide Manuel. Their aim is to get to New York where Rolf's mother is waiting for them. Ludwig is captured on the road leaving Rolf and Manuel are on their own to face a daunting and dangerous journey. It is a journey which develops a bond and a friendship between the two young boys as they learn to trust each other and learn from one another. The Path is inspired by true events.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 240

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Young Dedalus

General Editor: Timothy Lane

The Path

The translation of this work was supported by a grant given by the Goethe-Institut.

Published in the UK by Dedalus Limited

24–26, St Judith’s Lane, Sawtry, Cambs, PE28 5XE

www.dedalusbooks.com

ISBN printed book 978 1 915568 59 5

ISBN ebook 978 1 915568 75 5

Dedalus is distributed in the USA & Canada by SCB Distributors

15608 South New Century Drive, Gardena, CA 90248

Dedalus is distributed in Australia by Peribo Pty Ltd

58, Beaumont Road, Mount Kuring-gai, N.S.W. 2080

Der Pfad, by Rüdiger Bertram © 2017 by cbj, a division of Penguin Random House Verlagsgruppe GmbH, München, Germany.

Translation copyright © Claire Storey 2025

First published by Dedalus in 2025

The right of Rüdiger Bertram to be identified as the author and Claire Storey as the translator of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Elcograf S.p.A.

Typeset by Marie Lane

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The Author

Rüdiger Bertram was born in Ratingen in 1967. After completing his studies in History, Economics and German Studies, he initially worked as a freelance journalist. Today he writes screenplays and has published numerous successful books for children. He lives in Cologne with his wife and two children.

The Translator

Claire Storey translates from German, Spanish and Catalan into English, specialising in middle grade and young adult literature. She has translated books from countries including Argentina, Austria, Germany, Mexico, Spain and Uruguay. Claire volunteers in schools talking about careers with languages and was named Outreach Champion 2021 by the Institute of Translation and Interpreting.

Contents

Prologue

Marseille 1941

The Café

The Raid

Departure

The Train

An Argument about Adi

In the Mountains

Patrols

The Mountain Pass

On the Way

The Reunion

Esther

The Bear

The Tube

In the Lav

The City

The Bookshop

The Diamond Cutter

The Exchange

The Party

Epilogue

Prologue

Hitler came to power in 1933 and many authors were declared enemies of the people. In fact, they were not enemies of the people but of the Nazis. Their books were burned. Many of them fled abroad. A lot went to Paris and they watched events unfold in their homeland.

In 1940, Hitler’s army—the Wehrmacht—stormed into France. The German refugees were now the enemy and were locked up in camps. As the Wehrmacht occupied Paris, the French guards fled the camps and the prisoners escaped south towards the Mediterranean.

Shortly afterwards, a ceasefire agreement divided France. The north was under Nazi German occupation, while the south remained free.

Officially, the Nazis had no say in the south. Unofficially, Hitler’s secret police were everywhere. The refugees met in cafés in Marseille’s port, waiting for documents that would allow them to travel to the USA or South America. Thousands were stranded there. Rolf and his father Ludwig were two of them.

Marseille 1941

The best thing about Marseille is the sea, thought Rolf. In Paris they had been nowhere near the sea, so this was a jolly good improvement. All Paris had to offer was the Seine—a stinking river—and Rolf wouldn’t have considered dipping even a toe in there, not in a million years. Back when he had lived in Berlin with his parents, they had often taken a day trip to Wannsee and the lake on the edge of the city had seemed enormous. But it had shrunk in comparison once he had seen the Mediterranean Sea in Marseille.

From their hotel, Rolf and his father Ludwig walked fifteen minutes downhill to the port and a little further beyond to reach the small sandy beach that the French called Anse des Catalans. To the left, the beach was bordered by an ancient fortress tower and in the sea directly in front of them protruded a narrow seawall made from piled-up rocks. Rolf had once tried to swim out to it, but he’d given up about halfway there; it was much further than it looked.

To reach the beach, he and his father had to climb down a couple of well-worn stone steps. Near the steps was a brightly coloured beach hut in which they put on their bathing suits. Adi, Rolf’s fox terrier, scampered about impatiently by the door waiting for his owners to come out again.

A few older ladies sat on their deckchairs, staring out to sea as they chatted, but Rolf could not see anyone else bathing in the water, which was just how he liked it. He and his father had the Mediterranean to themselves.

Rolf and Ludwig spread out their towels on the sand and ran into the water. Adi leaped after them but stopped at the water’s edge. Father and son waded deeper into the waves. It was spring, the air was warm, the water too, once they got over the initial cold shock.

“Come on, Papa! It’s not so bad once you’re in.” Rolf was already in the sea with the water up to his chest, while Ludwig stood only up to his knees.

“That’s a complete fib!” Ludwig wrapped his shivering arms around his plump stomach. “I wouldn’t be surprised if an iceberg floated past.”

“And there was me thinking adults had more blubber than children to keep them warm,” teased Rolf, grinning.

“You just wait ‘til I get you!” Ludwig took a few strides towards his son but stopped again as the cold water reached his thighs.

“Let me help you!” Rolf skimmed an oncoming wave with the flat of his hand, showering his dad with water. Ludwig shrieked as the cold droplets hit him and then chased towards Rolf, laughing. Adi ran to and fro along the sand yapping as father and son wrestled in the water. Suddenly, Rolf slipped out of his father’s grasp and dived out of sight.

Ludwig looked around him, searching, but he couldn’t see his son anywhere. Worried, he spun around in circles calling, “Where are you? It’s not funny anymore!”

Rolf swam a wide arc around his father and launched himself onto Ludwig’s back. Ludwig tried to wriggle away but he couldn’t shake his son off. Rolf was clutching tightly around his father’s neck and only let go when Ludwig lost his footing and they both went crashing into the water.

Rolf loved splashing around in the sea with his father. War was raging across Europe, people were dying every single day and many more were fleeing. But right there, right then, as they fooled about in the sea, for a few moments, Rolf could forget everything.

As the twosome waded wearily back out onto the sand, the older ladies with their deckchairs had disappeared. Only Adi was waiting expectantly for them and he hopped about excitedly as Rolf and Ludwig dried themselves off. Father and son then changed back out of their bathing suits in the hut and, with wet hair, they wandered down to the Old Port.

Ludwig spoke French and Rolf had learnt enough in Paris to be able to make himself understood, but he still couldn’t speak English, and that was the language they would need once they boarded the ship that would take them to New York. His father used their time as they were walking along to impart his own broken knowledge of the language to his son.

“Repeat after me,” encouraged Ludwig. “Gud murning.”

“Good morning,” muttered Rolf in English, bored. “We’ve done all this already,” he complained, switching back to German.

“We’re just recapping. Say, tank yu.”

“What am I thanking you for? Making me study on a beautiful day?”

“Very funny,” retorted Ludwig. “Come on, say it after me. You want to be able to speak to Mama when we see her again.”

“Do you think she’ll have forgotten how to understand German?” asked Rolf, worried.

“Of course she’ll still understand,” Ludwig reassured him. “But when we’re all together in America, we ought to speak their language.”

“Mama couldn’t speak any English when she left.”

“She’s a dancer; it’s not so important for her, but it’s different for me. I’m a journalist. I write, and if I do that in German, nobody in America will be able to read it. And you should learn the language, too. You want to make new friends over there, don’t you?”

“Do you think Mama is alright?”

“Of course she’s alright. Whatever makes you say that?”

“Why hasn’t she written to us then?”

“The fact that letters from her aren’t getting through to us here doesn’t mean she isn’t writing to us.” Ludwig lay his arm around his son’s shoulder. “You know how it is.”

Rolf nodded. He did know how it was.

“What are we doing now, Papa?” asked Rolf once they reached the port.

“What we always do,” replied Ludwig. “Let’s go to the café.”

“Ugh,” sighed Rolf. “You all just talk and talk and talk. It’s so jolly boring. Can I at least have a croissant?” he asked.

“If the café has some and they’re not too expensive,” replied Ludwig, wearily counting the coins in his jacket pocket. “There weren’t any yesterday.”

“Or the day before, or the day before that,” added Rolf.

Rolf wondered when the last time had been that he had not only ordered a croissant in the café but had actually been given one. He was so deep in thought that he didn’t notice the man walking towards them along the harbour road. He was wearing a grey suit which looked rather worn. Most of the men and women who sat around in the cafés in the port of Marseille had bought their shirts, jackets and trousers in Berlin or Paris, as his father had done with his navy-blue suit, and you could see the signs of wear in the jacket and trousers.

“Ludwig?! Is that you?” The stranger stopped in front of Rolf’s father.

“Hans? Hans!” cried Ludwig and he hugged the man, laughing, before turning to Rolf. “This is Hans, a colleague from Berlin. We both write for the same newspaper.”

“Your son?” asked Hans, pointing to Rolf. “The last time I saw him in Berlin he couldn’t even walk. He was only this big.”

Hans held his hand out about three feet from the ground. Rolf gave a lopsided grin; that wasn’t quite true. He had been seven when they fled Germany five years earlier, and clearly he had been able to walk by then.

Rolf watched the fishermen as they hauled their catch out of the boats. It wasn’t the first time his dad had met acquaintances on their journey and it surely wouldn’t be the last. There weren’t that many routes out of Europe to reach America and it was only logical that they would meet people on the way. People who had made it out of Germany in time, at least—Rolf knew that, too.

The men embraced a second time and then studied each other for a long moment.

“I feared you might be…” Ludwig didn’t finish his sentence.

“Codswallop. You can’t get rid of weeds that easily! I arrived yesterday,” replied Hans. “What are you doing here?”

“Holiday!” Ludwig replied and he laughed as he saw the baffled look on Hans’ face. “Nonsense, I’m here doing what we’re all doing. I’m trying to get together the necessary papers to travel to America with Rolf.”

“Is it dangerous here in Marseille?”

“No more than anywhere else, although there do seem to be more brown cats moving around.” Rolf’s father gestured with his chin towards a black car rolling steadily down the harbour road. On the back seat sat a man wearing a brown German uniform. The vehicle drove by them so closely that Ludwig and Hans could even make out the swastika on his jacket. They both quickly turned away so the man inside couldn’t see their faces.

“Really? Where are the cats?” asked Rolf curiously.

Ludwig ruffled his son’s hair and exchanged an anxious look with Hans.

“Haven’t you seen them sitting along the harbour? They’re always sitting near the fishing boats, hoping for a sardine or two.”

“Oh, you mean those cats,” and Rolf glanced around for Adi who couldn’t stand cats and had chased more than one of them around the dock.

“And there are more and more mice,” continued Ludwig. “They’re coming from all over. And if the mice have the wrong papers, or none at all, then they quickly end up caught in a mousetrap. The French cats are working with the German ones, even if it’s not official. The noose is getting tighter,” said Ludwig quietly, almost in a whisper. Then he asked out loud, “How long have you been here in Marseille?”

“Since yesterday. Where’s Katja? Is she here, too?” replied Hans.

“No. Katja was with us in Paris and from there she travelled to New York. She wanted to get everything ready for us. The idea was for us to follow later, but sadly Herr Hitler has changed our travel plans a little. Our suitcase was packed and ready to go, but then he marched into France with his army, and we had to make a bit of a detour,” explained Ludwig.

Rolf’s ears had pricked up again at his mother’s name, but only briefly; he had heard this story many times before. He had finally found Adi. The dog was sniffing at a dead squid which had been tossed onto the quay by a fisherman. The Frenchman cast Rolf a warning glance and Rolf knew that the fisherman wouldn’t think twice before launching the dog into the water with a swift kick if Adi didn’t move away quickly.

“Leave it, Adi! Come here, now!” yelled Rolf.

The dog jumped, left the squid and ran back to his young master.

“Your dog’s called Adi?” asked Hans in astonishment. “Like the abbreviation of Adolf? Adolf Hitler? Don’t you think that’s a little… well… inappropriate?”

“How so?” shot back Rolf and he knelt down next to his terrier on the ground. “Be a gentleman, Adi! Come on, do it for me.”

Adi sat back on his hind legs and pawed at the air. Rolf reached out for his right paw and shook it cheerfully.

“Very good, Adi,” praised Rolf. “And now, play dead!”

The dog lay down on his side and stuck all four legs out straight. He lay on the ground completely motionless.

“If only it was that easy with the real Adolf. Was that your idea?” Hans asked Rolf, laughing.

“No, Adi belongs to my mother,” replied Rolf.

“Katja left him here so Rolf had something to snuggle up to when she wasn’t there. Rolf’s taught him a few tricks and promised to give him back once we reach New York,” explained Ludwig.

“And I’ll keep my promise too!” confirmed Rolf happily.

He gave Adi a gentle pat and the white fox terrier sprang back onto his four legs and began barking loudly as if to prove to anyone watching that he had only been pretending to be dead.

The Café

“Bonjour! Do you have any croissants today?” Rolf greeted the owner in French as he and his father entered their usual café.

Around the port there were numerous cafés and neither Rolf nor his father could quite explain why exactly this one was their favourite. All day long it was filled to bursting, but so too were the other places nearby. The owners of the cafés and bistros made their living off the steady stream of refugees, even though many of their customers stayed for hours while buying just a single cup of coffee or glass of wine.

“Do you have any croissants?” repeated Rolf. It was so noisy in the café that the server hadn’t heard him properly.

“Did you hear that? The young man wants to know if I have any croissants! There are so many in the kitchen it would take you days to eat them all. And then you would have a stomach ache and spend a week in the lav,” replied the owner, winking at Rolf’s father.

From the very first day, the two men had hit it off. Rolf put it down to the fact that both men liked to laugh, and both were as plump as each other. Most of the other guests were gaunt and serious, their faces haggard. Somehow Ludwig had managed to keep both his sense of humour and the extra pounds.

“Seriously?” asked Rolf in earnest, having missed the twinkle in the older man’s eyes.

“Well, about as serious as the news that Hitler voluntarily pulled his troops back yesterday and apologised if he has caused any inconvenience over the last few years,” replied the café owner, laughing.

“Oh, jolly funny,” grumbled Rolf sarcastically, disappointed.

“Come on, he didn’t mean to upset you. It was just a joke.” Rolf’s dad tried to appease him. “There’s far too little laughter around here.”

“We don’t exactly have a lot of reasons to laugh,” interjected a man standing near the bar. “Marseille is a pitiable case in point. We flail around here like fish caught in a net. The Nazis need only haul in their catch and we’re all done for.”

“But they haven’t caught us yet, Horst,” replied Ludwig. “And so long as we can still laugh, we’re not lost. You should try it sometime instead of moping around here with a face as long as a wet weekend.”

The man whom Ludwig had called Horst snorted disdainfully and turned back to his conversation with the man next to him. Rolf only grasped bits of what they were talking about, but if he wasn’t very much mistaken, they were discussing the same thing most people here talked about: the best way to get out of France and how to gain entry into the USA or countries in South America. Rumours circulated of refugees being turned away because their documents weren’t in order, or because they didn’t have enough money to bribe the customs officers. The whole café was like a hive where rumours flew in and out like busy bees.

“Forgive me, young man, I didn’t mean to upset you,” said the café owner. “You know flour and butter are in short supply at the moment. And no flour and no butter means no croissants,” he said, sliding a lemonade across the bar to Rolf. “Here, for you. On the house.”

“Thanks,” mumbled Rolf and he took a sip; all that swimming had made him thirsty.

Ludwig greeted a couple who were seated at a table reading a newspaper together. The woman was wearing a hat and a flowery dress. The colours were so faded that the flowers on the fabric looked like they were withering. Rolf’s father knew most of the people who drank in their café and had a story or two to tell about almost all of them. Horst, the gloomy man at the bar, was a playwright. Back in Berlin, the great, up-and-coming career that had been predicted for him was cut short when the Nazis came to power and banned all performances of his plays. At the table by the wall sat two chess players silently contemplating their next moves. They had been professors in Vienna, and the woman with the hat and the faded summer dress was a famous film star who hadn’t set foot in front of a camera since fleeing Germany.

“Wait here,” said Ludwig, “I just need to speak with the couple over there at the front.” Rolf’s father slipped between the chairs and tables over towards the couple reading the newspaper.

Rolf stayed where he was at the bar holding Adi under one arm and drinking his lemonade when he spotted a blonde lady at a different table. She had her back to him and from a distance, she reminded him of his mother. He crept nearer, wanting a better look, but close up, she lost any of the former resemblance. The lady had a fine paintbrush and was painting a stamp onto an identification document. As she sensed Rolf behind her, she turned and smiled at him.

“Hello. I’m Anna. Who are you?”

“My name’s Rolf. Isn’t that illegal?” asked Rolf, pointing to the false seal she was painting.

“Completely and utterly illegal,” answered the woman with a broad smile.

“Aren’t you scared they’ll catch you?”

“Here?” The woman laughed. “Half the people around here have false passports. And the other half sold them the passports! No, I’m not scared. But wait, stay there, just like that. Don’t turn around.”

“Why?” Rolf gave a terrified glance over his shoulder towards the entrance. “Is it the police?”

“No, no, don’t worry. I just want to draw you.” The lady slid the document she was working on to one side and reached for a blank piece of paper.

Rolf turned his head to see what she was drawing, but when he moved, the woman tutted loudly and shielded the paper from view, so he couldn’t catch a glimpse of the drawing.

Ludwig had finished his conversation and now joined them. He bent over the paper and nodded approvingly.

“Very good, Anna,” praised Rolf’s father.

“Can I see it yet?” asked Rolf.

Anna laid the sketch on the table for Rolf to see his portrait. It wasn’t all that easy to recognise which was the boy and which the dog. Anna had painted them very similarly, both with exaggerated noses and ears.

“But I don’t look like that at all! And neither does Adi!” cried Rolf.

“Yours?” Anna asked Ludwig.

“My pride and joy,” replied Ludwig.

“The dog or the boy?” asked Anna with a teasing smile.

Ludwig returned the smile and turned to Rolf. “The lady who created this hilarious picture of you and Adi was a famous artist back in Berlin. Now here she is, sitting in Marseille like us, falsifying documents.”

“That too is a great art!” remarked Anna.

“Well, we don’t wish to distract you from your latest work of art any further. We’ll see you in America,” said Ludwig, bidding her farewell.

“Let’s hope so!” replied Anna, handing Rolf the caricature.

“Thank you.” Rolf folded the paper, stuffed it in his jacket pocket and left the café with his father. At the door, he spun round one last time to look at Anna. She waved and then settled back to the false document in front of her.

“So? When are we going to go and meet Mama?” Rolf asked as they climbed the hill back to their hotel.

“Soon,” answered his father wearily.

“Why only soon? Why not straightaway, Papa?”

“Because it’s not time. Not yet.”

“Don’t the Americans want us after all?”

Ludwig stopped a moment for a breather.

“No, they do want us,” replied Ludwig as soon as he had enough breath to speak. “They have even invited us to go. But the French want us, too, and they won’t let us leave. They aren’t handing out exit passes to Germans anymore, I discovered that just today.”

“Do we need one of those?”

“Well, without the correct stamp in our passports, we won’t get over the border. And if we can’t get over the border, then we can’t get out of beautiful France.”

“So what now?” asked Rolf anxiously.

“Don’t you worry, it’s not that bad,” said Ludwig. “We just need to think about things differently.”

Their hotel room was on the second floor. In it was a bed, a desk with Ludwig’s typewriter, a wardrobe, a settee and a wash basin. The thing Rolf loved most of all was the little balcony. It was just big enough for them to take two chairs and sit outside. From there, Rolf could look down onto the broad boulevard. Looking left, he could see the wide steps leading to the train station and looking right, his gaze was lost among the treetops growing outside his window. If Rolf were to stick out his hand, he would be able to touch the leaves.

“With no valid exit pass, there are two ways to get out of France.” Ludwig sat down on the chair next to Rolf with Adi curled up comfortably at his feet.

“Steal a plane or commandeer a U-boat?” suggested Rolf.

“That makes it four then,” Ludwig laughed.

“What are the others?”

“Option one, we wait here for a ship to take us secretly across the Mediterranean Sea to Africa,” answered Ludwig.

“Why do we need a ship? We could just swim,” suggested Rolf.

“It’s a little too far.”

“What’s option two?”

“We go over the mountains to Spain.”

“Is that as far as travelling to Africa?”

“No, it’s much closer. Once we’re in Spain we can take a train to Lisbon in Portugal and from there we can board a ship bound for America.”

“I vote mountains,” stated Rolf.

“Me too,” agreed Ludwig. “There aren’t actually any ships leaving Marseille, much less any U-boats or aeroplanes that could take us away from here.”

They both looked down into the street below where people were walking along the pavement beneath them in the fading light.

“Will we have to climb?” Rolf asked after a while.

“No, it’s more of a long walk,” explained Ludwig. “Do you see that man down there, the one with the hat?”

“They’re all wearing hats! Which one do you mean?” asked Rolf.

“The one in the grey suit. Good or evil?”

Good or Evil was one of their favourite games. Rolf and his father would randomly select a person off the street and decide whether that person belonged to the goodies or the baddies: for or against Hitler.

“Jolly good,” said Rolf. “He has a thick book under his arm.”

“I think so too,” remarked Ludwig. “Your turn to pick.”

“That lady over there, the one sweeping her porch.”

“Evil,” replied Ludwig without too much consideration.

“Why?” asked Rolf.

“Didn’t you see how she shooed away the poor man who accidently took a wrong turn into her yard?” explained Ludwig, glancing at his watch. “Anyway, it’s about time you went to bed.”

“What about you?”

“I have to go and do something.”

“Speaking to strange ladies? I’ll tell Mama when we get to New York,” grinned Rolf.

“Tattletale,” replied Ludwig, grinning back.

“What are you doing then, getting us some walking sticks?”

“Warm, very warm.” Ludwig stood up, crouched down next to Adi and stroked the terrier softly behind the ears. “Keep an eye on the cheeky boy, do you hear?”

“It’s you he needs to keep an eye on,” said Rolf.

“I’ll be fine.” Ludwig kissed his son on the forehead. “I’ll be back soon. Sleep well.”

Just as he was leaving the room, he turned back. “And the dog is not allowed in the bed, understood?”

“I know, Papa,” replied Rolf.

“That’s alright then. See you later.”

The door closed and Rolf waited a few moments. Then he stood up, lifted Adi up off the floor and then climbed into bed with the terrier.

“We’ll see Mama again soon. Just a little walk and a boat ride over the Atlantic. Don’t worry, we’ll make it. I’m here with you.”

Rolf gave Adi a kiss, snuggled up tightly to his dog and began reading The 35th of May by Erich Kästner.

Rolf had met Kästner several times in Berlin. Whenever Rolf accompanied his father to his favourite coffee house, the chances were high that some famous author or other would also be there, writing their books, chatting with friends or dictating letters to their secretary. Back then, Rolf was too young to understand who his father was speaking with. He had vague memories of the friendly man who, during one such visit, had taken a copy of The 35th of May out of his pocket, licked the nib of his pencil and written a dedication:

For little Rolf!

Always look forwards

And remember,

Whatever lies behind you

Only weighs half as much.

Yours, Erich Kästner

Rolf remembered being annoyed at being called little Rolf but at the same time he was immensely proud, even though he didn’t particularly understand what the dedication meant. He had asked his father who smilingly replied, “It’s your dedication, not mine. Sooner or later you’ll work out what Erich means.”

The signed book was the only one of his many books that Rolf had been able to save for his journey from Berlin to Paris and then onwards to Marseille. His mother used to read to him out loud from it and now Rolf read it to himself. The fact that he knew the book almost off by heart didn’t bother him at all. If anything, he enjoyed it even more. So much had changed since they had left Berlin, yet the words in the book always stayed the same.