Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

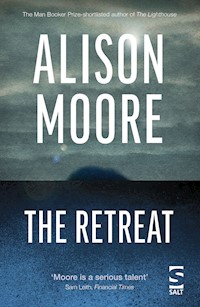

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Since childhood, Sandra Peters has been fascinated by the small, private island of Lieloh, home to the reclusive silent-film star Valerie Swanson. Having dreamed of going to art college, Sandra is now in her forties and working as a receptionist, but she still harbours artistic ambitions. When she sees an advert for a two-week artists' retreat on Lieloh, Sandra sets out on what might be a life-changing journey.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 218

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE RETREAT

ALISON MOORE

For Penny and Sarah

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Liel was an in-between place. Lying one hundred miles from the English coast, the island resembled Sandra’s known world but it had its own currency and its own system of car number plates; its post boxes were blue and its telephone boxes were yellow. It was not far from France but was not French. The island had its own distinctive language but Sandra had only heard English spoken there, though in a foreign accent. Some of the street signs and house names were in English and some were in French, or at least it looked like French. She did not, when she first holidayed there, know much French. At school, she learnt to say Je suis une fille unique, which sounded better than it was, and J’ai un cochon d’Inde, although she did not have one. Later still, she learnt phrases from a book: Good morning and Good afternoon, and I must go now and Go away! She could say A table for one please and I didn’t order this and Can I have a refund? She could say Can you help me? and I’m really sorry and I don’t understand. She imagined herself stranded with these phrases, hoping she would be all right.

It was from the dining room window of Liel’s Sea View hotel that Sandra first saw the smaller island of Lieloh, sunlit on the horizon. It looked like the dome of a sea monster’s head, as if it were crouched on the seabed and might suddenly rise up. ‘What’s that?’ she asked. Her mother put down her butter knife and turned to look. She said it was only an island and that Sandra should finish her soup. ‘But what island is it?’ asked Sandra. Her mother said it must be Lieloh and that her soup would go cold. Sandra, stirring her soup, said, ‘Can we go there?’ Her mother said they had almost finished their holiday and that they already had plans for their remaining days, and her father added that it would not have been possible anyway because the island was privately owned and if she did not finish her soup it would be taken away and then she would be hungry. Sandra lifted a spoonful of soup towards her mouth, then lowered it to ask, ‘Who owns it?’ Her father said Lieloh belonged to the Swansons, who were very rich. Valerie Swanson had been in films, said her mother, although she had to be in her sixties by now, and in her retirement was living on her own island in a house of her own design; and she was famous for her lavish parties, to which only artists were invited. Sandra pictured Valerie Swanson, star of the silver screen, sleek haired, silk gowned, standing in the doorway of her mansion, or on a patio looking out at her extensive and immaculate garden, or on a balcony watching the sun set, as her party guests mingled. Her mother said boats were seen out there, and Sandra imagined them dotted around the island like moons around an alien planet, haunting the shore like the boats that gathered outside Brigitte Bardot’s beach house, hoping to catch a glimpse of her. But, added her mother, looking at the undisturbed view, there didn’t seem to be any there now.

The closest Sandra could get to Lieloh was to walk along the sea front and down to the docks. Through binoculars, she could see trees, and she thought of the island of happiness, which no longer appeared on maps but whose hills and woods, and glimpses of chimneys and curls of smoke, had been described by an antiquarian who had seen with his own eyes this island where contentment was assured. Sandra had read all about it, but could not remember where it was said to be. Somewhere beyond that barrier of greenery was the home that Valerie Swanson had built with her film-star earnings. Sandra took a photograph, but when she got back to the mainland and had her pictures processed, Lieloh just looked like dark clouds on the horizon.

In adulthood, she honeymooned on Liel. Alex had suggested a smart hotel in the middle of the island, but Sandra wanted something further out; she wanted to stay in the Sea View. She agreed that it was old-fashioned but it was right on the coast, and every morning they woke to the sound and smell of the sea and the squawk of the gulls, which Alex said would drive them mad. At the dining room window, Sandra looked for Lieloh as if not entirely expecting to find that it was still there, as if it might turn out to have been a childhood invention or a mirage, but there it was. She pointed it out to Alex, but he did not see the attraction. It was rather small, he said, and far away. He felt, perhaps, the same way she did whenever he drew her attention to babies and toddlers and told her how nice it would be to have one of their own, to have a family. ‘I’ve always wanted children,’ he said, ‘haven’t you?’ She hadn’t really, and had not thought much about it. She had never even held a baby.

Once upon a time, she had wanted to go to art college, to become an artist. She had won certificates for her art at school, and, in her final year, a prize for the greatest effort. But it was a precarious kind of life; as an artist, she might struggle to support herself. She ended up in an office, on reception, but around the edges of her workday she sometimes thought about making some art, and might sketch the mug she’d just drunk from, or the ketchup bottle, still life; she tried sketching the cat but had trouble with anything that moved. Occasionally, the start of a new year prompted her to sign up for an evening class. The one with which she struggled most was life drawing, to the point that she felt compelled to apologise to the life model for mangling him. He didn’t care, he said; he was only there to make some cash. He told her he was really an actor, and that he was going to go to LA; he was going to get into films. She smiled, remembering her own teenage daydreams, and told him she had once thought of going to art college and becoming an artist.

‘You should,’ he said.

‘Do you think so?’ she asked, looking sceptically at her work.

He shrugged again and said, ‘If that’s what you want. It isn’t too late. Live the dream!’

She said it was impossible – how was she supposed to live? She had a mortgage and bills to pay; she had responsibilities at home and the possibility of a promotion at work.

At the final class, before he left for LA, he said, ‘Look out for me.’

Years later, finally deciding that she had no talent for people, life drawing, portraiture, she bought her first watercolour kit and took a watercolour seascapes class, whose only downside was that the classroom was in a building that could hardly have been further from the sea. When she and Alex returned to Liel, she took her kit with her, and discovered an artists’ group that was open to holidaymakers, and to anyone who felt inclined to drop in. She devoted some hours to working alongside them in a community centre, while Alex went sightseeing alone. It was jolly and friendly but vaguely unsatisfying and she felt that was because she and everyone else were free to drop in and out, to come and go. She wanted something more committed. During a coffee break, she sat flipping through a magazine featuring artists and musicians and writers, all of them young and beautiful, and articles accompanied by gorgeous illustrations: flowers and clothes and abstract designs; a night sky to accompany an item on astronomy; bare branches framing a piece about gloves; a Welsh beach scene whose colours were glorious, the cold greys of the lowering sky and the sea turning to white against the earth tones of the headland, and on the sand, the little figures of a family, hand in hand, walking away, their shadows long behind them. Sandra imagined the artist labouring over this artwork in her own studio, at a desk at a window with plenty of light, with a kettle and a jar of coffee nearby, and a cat, there always had to be a cat. That would be her ideal job, she thought. She turned the page, and came face-to-face with an advert for an artists’ retreat on the island of Lieloh. She stared, hardly believing her eyes. There was a picture of the house. It was not exactly a mansion but it was a big house, and attractive, its walls eggshell-blue and sunlit, its aspidistra-green front door framed by a rose arch. She tore out the advert, to show Alex this invitation to visit an island that for so long had been out of bounds.

‘I guess Valerie Swanson must be dead by now,’ said Alex.

‘I wonder what it’s like,’ said Sandra, ‘living on an island.’

‘You live on an island,’ said Alex. ‘Britain’s an island.’

‘Yes,’ said Sandra. And she had stayed on Liel a few times. But she was thinking of somewhere smaller, somewhere unspoilt; she was thinking of Lieloh. She was looking at the advert, at the PO Box number to which bookings could be sent.

1

Carol is going to miss the city. She will miss the theatres and the restaurants and the bars. She has favourites but most of all she appreciates the variety, the choice. There is always some new venue or show opening, and a friend to go with. The cinema is advertising a film that she would have liked to see but which has not yet been released. She will have to watch it some other time, at home, on her little TV.

She will even miss the buskers, she thinks, dropping some change into a music student’s open violin case.

She doubts she will miss the crowds, the pavements choked with meandering pedestrians who, as the rain starts, open umbrellas whose spokes go for her eyes.

She will not miss the prices, the tourist tat, the congestion, the dirty air. She will not miss this weather. The puddles are spoiling her new calfskin shoes, wetting her tights. But then, she supposes, the weather will be much the same where she is going.

She will miss her son, of course. She will miss Jayne, and their lunches, during which Jayne listens patiently while Carol complains. Mostly, she complains that, although her short stories are well-received, she is almost unknown, and that the novel she has always wanted to write is still not written. She writes fantasy. What she really wants is to write a series of fantasy novels.

Carol keeps reading interviews in which an author will say that their novel came quite easily, that it wrote itself. But a novel does not write itself. She writes her novel. Or rather, she thinks – dashing between two cars, ignoring the honking – she does not.

It just seemed to fall out of me. They make it sound like childbirth, during which she knows there must have been pain because she had to ask for an epidural, but she cannot remember the pain itself, what it felt like. There were hours and hours of labour but they have concertinaed in her mind. She knows she tore badly and vomited repeatedly but mostly what she remembers is the baby landing on her chest, and her holding, both very suddenly and at the end of nine long months, this surprising life. Her third-degree tear has long since healed and is invisible to her now. She never did give her little boy a sibling.

Now it’s just her – with her son grown and gone, and her husband gone, and even the dog’s heart finally giving out – she could have a little flat, that would be enough. She could grow flowers in a window box, go for strolls, see Jayne, visit her son and his family, read gossip magazines and other people’s bestsellers, cook and bake and sleep well. But: she wants to write. She wants to write the novel that for years she has been talking about writing. She wants to appear in window displays. She wants to be translated and read around the world. She wants a Netflix series, or to see her work on the big screen. She does have ideas, and she does get started, but she finds it desperately hard to really get anywhere, and then it is too easy to give in to distractions.

She steps aside now, out of the crowd, out of the rain, into the peace and comfort of the restaurant in which Jayne is waiting to hear her news.

2

Leaving home with her rucksack and a satchel, Sandra feels as if she were going on a school trip, as if she ought to have labelled her belongings, to have ‘SANDRA PETERS’ sewn into all her clothes, including her underwear; or she feels, closing the front door quietly because it is still early, as if she were running away.

She drives herself to the airport, leaves her car in the long-stay car park and catches a late morning flight from the mainland to Liel. Outside Liel airport, she waits in the rain for a bus that will take her to the south coast. There is no shelter, just the stop. She puts up her hood. When the bus arrives, she requests a single to the port and settles into a seat near the front. She watches the rain spattering against the window and thinks Here I am, on my way to Lieloh. She smiles at the thought. Here she is, on her way to live in Valerie Swanson’s house, among artists, in a little community. She imagines them supporting and inspiring one another, fetching vegetables from a kitchen garden, cooking together. She wonders what they will be like, these strangers with whom she will be spending the coming fortnight.

Near the port, the houses become smaller and more functional: single-storey boxes, with plain doors and windows with storm shutters. The Sea View hotel stands alone, looking decorative and fussy beside the houses, and more exposed. This is where Sandra will put up, before catching the midweek ferry to Lieloh.

She climbs the damp stone steps to the foyer. The receptionist has been there for years, in the same outdated uniform. ‘Yes, here you are,’ she says, finding Sandra’s booking on the computer, handing over the key to a room that turns out to lack a sea view. It could be worse though, and it’s only for one night.

When Sandra wakes on the Wednesday morning, it takes her a moment to get her bearings. She opens the curtains and sees sunshine, though it is cold enough, she realises later, for a jumper. She has a good breakfast in the dining room and then returns to her bedroom and puts on the television news until it is time to check out. The Turner Prize exhibition is opening at the Tate. The shortlisted work includes an unmade bed which Sandra, sitting on her own unmade bed, does not feel she understands.

Her flat shoes are quiet on the paving slabs as she walks to the docks, picking up a sandwich on the way. She has been instructed to wait at the top of the furthest ramp, to catch the noon ferry. She can see a ferry at the bottom of the ramp. It is smaller than she was expecting but it is bound to be hers.

Sandra sits down on a bench and waits, full of the nervous excitement she feels before job interviews (during which she is likely, perhaps as soon as she enters the room, or perhaps when the interview is nearly over, to commit a faux pas, to say the wrong thing, to give the wrong impression) or dates, though it’s a long time since she went on one of those.

‘Are you here for the retreat?’

Sandra turns to see who has spoken. A tall woman in a cheerful orange coat is taking a seat on the bench. ‘Yes,’ says Sandra. She smiles and adds, ‘I like your orange coat.’

‘Thank you,’ says the woman. ‘It’s apricot.’ She turns to look at the ferry and asks, ‘Is that the ferry to Lieloh?’

‘I think so,’ says Sandra.

Others are gathering now. There are two more women, who are standing together, and Sandra thinks Spiker and Sponge. Sponge looks heavily pregnant. Spiker has an expensive rucksack boasting sewn-on patches from all over the world, from cities and countries and continents that Sandra has never been to, and she speaks with a confidence that would prompt Sandra’s mother to say, as a disapproving aside, ‘She’s very sure of herself.’

And there are two men: one baby-faced in a camouflage jacket and combat trousers, the other bigger and hairier and ruddier, optimistically dressed in a tropical shirt and shorts and eating a packet of cheese and onion crisps.

‘This is the first time I’ve been off the mainland,’ says Sponge, sitting down on the other side of Sandra. She has a nasal voice and reeks of cigarette smoke.

‘It’s not my first time,’ says the man in the holiday clothes, ‘but it’s my first time alone.’

‘You’re not alone,’ says Sponge. ‘You’re with us.’

He tells them he’s left his wife and children, and Spiker says, ‘They’ll be all right. I’ve left my husband with two teenage boys and three dogs.’

‘No,’ says the man, ‘I mean, I’ve left them for good.’

‘Oh, I see,’ says Spiker.

‘It might not be for good,’ says Sponge. ‘You might go back.’

‘No,’ he says, shaking his head. ‘I won’t go back. I made my choice.’

Sponge turns to Sandra and asks where she’s come from. Sandra mentions her home town, which Sponge says she’s never heard of. ‘It’s a nice place,’ says Sandra, who had a happy childhood, in a house with a long garden with a stream at the bottom, but she couldn’t wait to leave. She lives in the suburbs now, with Alex, in a comfortable semi; they sometimes talk about escaping, but he just means for the weekend.

‘Have you been to Liel before?’ asks Sponge.

‘I’ve been here on holiday,’ says Sandra.

‘I couldn’t live on Liel,’ says Spiker. ‘It’s too quiet for me.’

‘It looked nice in pictures,’ says Sponge. ‘All beaches and sunsets.’

Sandra nods. ‘It’s lovely in the summer.’

‘It’s not how I imagined,’ says Sponge.

‘It’s too quiet,’ insists Spiker.

‘And rather cold,’ says Sponge.

‘Lieloh should be interesting though,’ says the woman in the apricot coat.

‘The house looked nice in the picture,’ says Sponge.

It would be her dream life, says Sandra; the retreat would be a taste of a perfect way of living. She begins to explain to them her vision of this group as a kind of artists’ colony, a community of artists supporting and inspiring one another, but they are being summoned. The six of them descend the ramp to the ferry, where men are waiting to take them across. The ferryman, who stands at the gangplank to help them aboard, is youngish but weather-beaten, with close-cropped brown hair and a new-looking khaki anorak zipped up against the elements. The other man counts them, as if in a group this small it might be possible to lose someone.

They find seats. The crossing from Liel to Lieloh will take less than an hour; it is not that far away, perhaps ten miles. It is too far to swim to – Sandra, at least, who tires after twenty lengths of the local pool, could not swim even half a mile in one go.

Sandra takes a seat next to the woman in the apricot coat, who says, as the ferry pulls out of the harbour, ‘I’ve never spent so long with strangers.’

‘Well, we won’t be strangers for long,’ says Sandra. ‘We’ll get to know one another soon enough.’

‘I’m Harriet,’ says the woman.

‘I’m Sandra,’ says Sandra, pleased to have made her first friend among the group.

‘Don’t be offended if I don’t remember that,’ says Harriet. ‘I’m terrible with names.’

The rumble of the engine and the gentle rocking of the boat is soporific. Sandra lets her eyes close and turns her face up to the sun, until she starts to feel woozy.

‘What do you do?’ asks Harriet, as Sandra opens her eyes.

‘I’m a visual artist,’ says Sandra.

‘I mean,’ says Harriet, ‘what do you do for a living?’

‘Oh,’ says Sandra. ‘I’m a receptionist.’ It’s all right. It’s not very satisfying but then it’s not very stressful either. Although sometimes it is stressful, when people are complaining, when they’re angry, and Sandra, behind the reception desk, feels cornered, is physically cornered, trying to keep her tone cool. ‘What about you?’

Harriet mentions the university at which she works, which is attached to an art gallery at which Sandra once saw an exhibition. It was an exhibition of sculptures that Sandra had been keen to see but which she felt, when she stood looking at them, she failed to understand. ‘That’s a common response,’ says Harriet, who visited the same exhibition and has written about the artist’s work.

Sandra suggests sharing a room in the house on Lieloh, but Harriet says no. ‘I paid for a single room,’ she says. ‘I don’t know about the others, apart from the men – the men have been put together.’ Sandra looks across at the other women, at Spiker and Sponge. They both seem friendly enough.

Everyone sets about eating whatever they have brought with them for lunch, though Sandra leaves most of her sandwich, putting it away in her rucksack for later: the soporific rocking has developed into a violent tipping sensation that makes her stomach feel like it’s falling through her feet, as if she were on some terrible ride at the funfair. She is acutely aware of the miles and miles of cold, dark sea into which she would not want to drop.

The ferry rises and falls, and rises and falls, on the relentless green-grey waves.

3

Jayne is waiting for Carol in the restaurant’s conservatory, where the branches of cherry-blossom trees reach along the walls and across the ceiling. It is like a stage set for A Midsummer Night’s Dream; it is like Max’s bedroom in Where the Wild Things Are. The trees are not real of course; the cherry blossom is not real.

There is jazz playing in the background, which Carol finds soothing. She joins Jayne at a table for two near the fireplace. There is a good fire going and the warmth just about reaches them.

‘Look at my shoes,’ says Carol, showing Jayne the damp calfskin, her damp tights.

Jayne sympathises. She has ordered wine, she says. They both know the wine here is good; if there’s one thing Carol cannot bear, it is substandard wine.

They browse the menu, and a waiter brings their drinks and takes their food order. Carol asks for the duck foie gras followed by the venison. They sip their glasses of pinot noir and Jayne says, ‘So tell me your news.’

Carol has been putting off this moment, knowing that her friend will try to change her mind, but it’s too late now, there will be no talking her out of it.

‘You’ve written your novel?’ prompts Jayne.

‘No,’ says Carol.

‘No,’ says Jayne, ‘I was joking.’

‘I’m going away for a while,’ says Carol.

‘That sounds ominous,’ says Jayne.

Carol laughs. She butters her bread and says, ‘Do you remember Roman?’

‘Roman with the good looks and the private island?’ says Jayne, making eyes at her friend. ‘I do indeed.’

‘That’s where I’m going,’ says Carol.

Jayne is agog. ‘You’re going to stay with Roman on his private island?’

‘Roman isn’t living there,’ says Carol. ‘He wants to sell it, but he offered me the chance to stay in the empty house in the meantime.’

‘You mean you’re going to stay there alone?’ says Jayne.

‘That’s the idea,’ says Carol. ‘It’s the perfect place to try and write my novel. There’ll be no distractions.’

‘No Jayne,’ says Jayne. ‘No boozy lunches. No lost afternoons.’

‘I’ll have nothing to do but write,’ says Carol. She expects Roman will visit her though; she would hope to have a little bit of company from time to time.

‘You’re going to lock yourself away in a room,’ says Jayne, ‘and not come out until you’ve spun all the straw into gold.’

‘Something like that,’ says Carol.

‘How long are you going for?’ asks Jayne.

‘As long as it takes,’ says Carol.

‘As long as it takes to sell the island or as long as it takes to write the novel?’ asks Jayne.

‘Either way,’ says Carol, ‘at the end of it, either I’ll return with a finished novel or I won’t.’

‘You’ll hate it,’ says Jayne, as the waiter arrives with their meals.

Carol smiles at her friend and picks up her cutlery.

‘But you can always phone me,’ says Jayne. ‘I’ll come and get you. In my private helicopter.’

They both laugh, while the fire dances in the grate and the rain hammers down outside.