7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

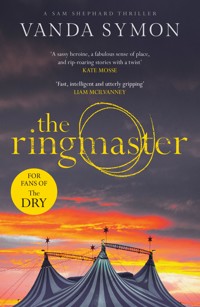

When a university student is murdered in Dunedin's university district, newly transferred young female police officer Sam Shephard is drawn into the investigation … The heart-stoppingly tense next instalment in the page-turning, international bestselling Sam Shephard series 'Finally, UK readers get to discover New Zealand's own Queen of Crime. Vanda Symon is a big talent and everything she writes is fast, intelligent and utterly gripping. This one's a cracker' Liam McIlvanney 'Fast-moving New Zealand procedural … the Edinburgh of the south has never been more deadly' Ian Rankin 'It is Symon's copper Sam, self-deprecating and very human, who represents the writer's real achievement' Guardian 'Antipodean-set crime is riding high thanks to the likes of Jane Harper and fans of The Dry will also love Vanda Symon's The Ringmaster' Red Magazine –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Death is stalking the South Island of New Zealand Marginalised by previous antics, Sam Shephard, is on the bottom rung of detective training in Dunedin, and her boss makes sure she knows it. She gets involved in her first homicide investigation, when a university student is murdered in the Botanic Gardens, and Sam soon discovers this is not an isolated incident. There is a chilling prospect of a predator loose in Dunedin, and a very strong possibility that the deaths are linked to a visiting circus… Determined to find out who's running the show, and to prove herself, Sam throws herself into an investigation that can have only one ending… Rich with atmosphere, humour and a dark, shocking plot, The Ringmaster marks the return of passionate, headstrong police officer, Sam Shephard, in the next instalment of Vanda Symon's bestselling series. –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 'An absolute must-have' Daily Express 'A sassy heroine, fabulous sense of place, and rip-roaring stories with a twist' Kate Mosse 'Vanda Symon is part of a new wave of Kiwi crime writers … her talent for creating well-rounded characters permeates throughout' Crime Watch 'Lively evocation of small-town life, with a plot that grabs the reader's attention with a heart-stopping opening and doesn't let go' The Times 'An absolute beauty of a read, well-written, absorbing, and extremely enjoyable' LoveReading 'Fast-moving New Zealand procedural … the Edinburgh of the south has never been more deadly' Ian Rankin 'Full of action and plenty of plot twists, but the star of the show is always the small but mighty Sam Shephard. With her dry sense of humor, indomitable spirit, and constant need to prove herself, Sam is the perfect heroine to root for … Atmospheric, emotional, and gripping' Foreword Reviews 'Symon follows up the terrific Overkill (2019) with this equally absorbing story … A fine thriller by a writer who deserves a larger audience in the US' Booklist

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 396

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Ringmaster

Vanda Symon

Contents

Prologue

‘Rosie, wait.’ He lengthened his stride to catch up with her. She turned and he couldn’t help but enjoy the immense smile that lit up her face as she realised who’d called after her.

‘Hey, this is a pleasant surprise. I thought you were working late tonight.’ She started to lean in to kiss him, but checked herself and put her hands in her pockets instead, a blush spreading across her cheeks.

She was such a pretty young thing, he thought; pretty and clever – a winning combination. They turned and continued walking together along Dundas Street, past the bottle-strewn fronts of the down-at-heel terraced houses inhabited by university students.

‘You know I don’t like you walking along that track by yourself when it’s getting dark,’ he said. ‘I thought I’d come and keep you company. I’d never forgive myself if something bad happened to you.’ It was early evening and the gloomy weather made the light lower than usual for this time of year.

She laughed, so melodic. ‘You worry too much. Nothing’s going to happen. Dunedin’s as safe as. Everyone takes this shortcut from uni to the Valley. Besides, walking through the bush helps me unwind – it’s so beautiful and serene.’

She had a point – the track was very picturesque. They turned into Gore Place and passed through the large iron gates into the enchanted realm of the Botanic Garden. The track meandered between the Water of Leith and the curve of the hill before it crossed over on to the flat expanse of the lower park with its lawns, flowerbeds and the impressive Winter Gardens. The route passed through lush native bush and on a fine day it made for a lovely stroll. The deserted playground by the gates was testament to the hour and to how drizzly the day had been.

‘I don’t worry too much,’ he said, pretending to be piqued.

‘Oh, you’ll trip over that lip if you’re not careful,’ she said, playing the game. ‘By the way, I like the new coat and hat. Didn’t even recognise you at first. You’re not getting hip on me, are you?’ Again the melodic laugh.

‘If you can’t beat them, join them, as they say. Maybe being around you youngsters all day is rubbing off on me.’ He made an attempt at a twirl and grinned at the girl’s yelp of delight. He stopped and turned to face her, taking a big breath as he chose his next words.

‘Look, Rosie, there is something I need to talk to you about. Something important.’ He saw a flicker of a frown cross her face and realised she thought it was bad news. ‘No, no. Nothing bad. It’s good news.’

She leaned forward, expectant. ‘You mean you’re finally…’

The crunch of approaching footsteps on the gravel path made her pause. They both stepped back slightly from each other, and he turned and looked up the path. He heard her say hello to the passer-by and then watched the back of the young man as he carried on towards the gardens.

‘Do you know him?’ he asked, when he thought the student was out of earshot.

‘No, just being friendly. It’s a big campus and despite what you may think, I don’t actually know everyone,’ she said. ‘Why, are you jealous?’

He gave her a ‘yeah right’ look and motioned with his head that they should keep on walking. They were now under the canopy of the trees, making their way along the path by what little light filtered through the dense foliage. ‘See how dark it gets in here,’ he said. ‘I really don’t like you walking this way now the days are getting shorter. You don’t know what weirdos could be here, lying in wait for a lovely creature like you.’

‘It’s very flattering that you worry so much, but I feel quite safe. If it’ll make you feel better, I’ll start walking along the road when it gets too dark. They shut the gates earlier in winter, so I won’t have any choice soon.’

They came to a massive pine tree, its branches thin and octopus-like, reaching out into the bush. A small path disappeared through the undergrowth beside it.

‘Come down here, where we won’t be disturbed. I really need to talk to you.’ He grabbed her by the hand and led her down the trail; she had to skip to keep up with him.

The gravel ended and they walked a hundred metres along a mown grass verge bordering the Leith until they came to a small clearing at the river’s edge. He looked around to make sure they didn’t have any unwanted spectators; he could see no one. His pulse began to beat faster; his face felt hot. He took her hands in his, wishing they weren’t both wearing gloves to ward off the chill; wishing he could feel her soft skin.

‘Look, you know I love you, and that you’re the woman for me. I haven’t been able to be with you as much as I’d like. And I realise you’ve been very patient about it. My … commitments have got in the way. But I’d like that to change.’

Her face lit up with that beautiful smile. ‘Oh, my God. You’re going to leave her, aren’t you? You’re finally going to leave her.’ She looked into his eyes, searching his face for a response. He simply nodded, and with that she threw her arms around his neck and he used the momentum to swing her off her feet. Landing on solid earth again, she planted a kiss on his mouth. Her lips felt cold, but incredibly soft.

He didn’t want to pull away, but he did, and laughed. ‘Wait, wait, there’s more.’ He stepped back, creating a space between them. ‘I want to give you something – a sign of my commitment, I suppose; a promise that you’re the woman I want to spend the rest of my life with. Close your eyes and hold out your hands.’

The sight of her – gorgeous, flushed with excitement, jiggling up and down – brought a lump to his throat and filled him with a moment of apprehension about what he was going to do. But no, he had come this far, had planned and worked so hard for this. He took a deep breath and reached into his pocket.

It only took a second to slip the already looped cable tie around her outstretched wrists and then to pull it tight.

In the time it took for her eyes to flash open and her to start saying, ‘What … what are you doing? I don’t…’ he had pulled the duct tape out of his pocket and ripped it open. He slapped it across her mouth and around the back of her head. By now, terror had registered in her eyes and she ducked down and turned, trying to escape and run. But he anticipated this, tripping her and making her fall elbows first to the ground. She tried to wriggle forward, but was hindered by a large rock in her path. He stepped over her squirming form, straddling her shoulders. Her damned backpack made the job more difficult, but he managed to grab her by the head and, despite her resistance, slam her hard over and over into the rock. There was a cracking noise and then silence. She went limp in his hands and he dropped her on to the grass.

Hands on knees and panting heavily, he had to hold his breath so he could listen and look around to ensure there had been no witness to his work. But all was silence and gloom.

He dragged her over to the Water of Leith and slid her in, holding her face down in case the cold of the water revived her.

It didn’t.

He waited a few minutes to make sure, but there was no more movement from his beautiful Rosie. He hadn’t tried it this way before, but it had worked a treat. In fact, it had been easier than he’d thought.

He was getting good at this.

1

‘What a bloody circus.’

Just when I thought I’d seen it all, here it was – a new page in the album of the ridiculous. The lion roared, despite the efforts of its keeper to calm it. The lion was in a cage. So was the animal-rights activist with the megaphone. He was busy announcing to all who would listen – not that anyone had a choice – exactly what he thought of the plight of the four-legged performers. The caged activist’s support crew, including someone in a gorilla suit, cheered and waved their placards with every expletive, provoking further roars from the lion. The immense and dangerously grumpy man being restrained by his colleagues had to be Terry Bennett, owner of the Darling Brothers’ Circus. I wasn’t sure who was the more menacing: the man or the lion.

The presence of television cameras and a sizable rent-a-crowd sure as hell didn’t help matters.

Fabulous.

‘What the hell is all this?’ Smithy said, as we wove our way through the hordes that had gathered to gawk at the entertainment sited at the southern end of the Kensington Oval. On any normal day, the expansive, lush green fields that were the Oval were home to cricket matches or football – awash with swarms of little kids and their overanxious parents yelling overambitious instructions from the sideline. Not today.

The circus was set up at the pub end and had that unmistakable carnival look, with strings of coloured lighting, enormous inflatable clowns, brightly painted animal trailers and the double-peaked, damned impressive big top that dominated the scene. Smithy looked less than excited by it all. ‘I thought the call-out was because of some students breaking into the lion cage. No one mentioned protesters.’

‘Looks like they’re an added bonus,’ I replied. Nice bonus. Normally we wouldn’t be sent out for a ruckus like this, but due to the Highlanders playing a Super Rugby game at the stadium, most of the regular officers had been called in for crowd control, so they’d had to dip into the CIB pool for this one. After a look around the motley mob here, I thought I’d rather be dealing with drunks at the rugby.

‘Well,’ Smithy said. ‘What do we tackle first?’

‘Ugh, I hate protesters,’ I said, my face screwing into a grimace. ‘Why don’t you go check the idiot in the cage, see if you can persuade him to make a graceful exit? Get rid of his cheerleaders too; mass evictions always were your speciality. I’ll talk to Mr Bennett.’

Smithy was built like the proverbial brick shithouse. He had an impressive set of cauliflower ears, courtesy of being front-row forward for his rugby team, and they complemented his don’t-mess-with-me face. People seemed to take his presence rather seriously, unlike mine. A barely five-foot-tall waif of a thing didn’t tend to have the same deterrent effect, even if she was armed with a mouth and wasn’t afraid to use it.

Smithy headed towards the vocal section and I turned towards Bennett. He was standing alongside the big top; a man-mountain surrounded by an interesting array of humanity. They only partially buffered the waves of anger radiating from him. Oh, how I longed for the rugby.

I sucked it up and went over to say hello.

‘Mr Bennett?’ I asked. He nodded. ‘I’m Detective Constable Shephard. You reported someone had tried to break into one of the animal cages?’

The flesh barrier parted in response to a grunted instruction and Terry Bennett shuffled forward until he towered above me.

‘First the fucking students, and now this bloody mob. How the hell am I supposed to run a show when all I get is idiot pranksters and bloody Nazi activists.’ His voice carried the gravel of a seasoned smoker. ‘And now the friggin’ TV is here, so if I go and belt one of the bastards, I’ll be the one getting crucified on the news.’ His breath confirmed my suspicion. ‘And where the hell are the rest of the police? What do you think the two of you can do by yourselves?’

I ignored the vote of confidence.

‘We’ll deal with the protesters; we’ll move them back out of the way. But first, I want to know about the lion-cage break-in. Is it true that you’re holding a couple of students? Can I see them, please?’

His face went a deeper shade of crimson.

‘Yes, we had the little shits, but when we tried to detain them, they said they’d have us for assault and kidnap charges. So we had to let them go – couldn’t even give them a good boot up the arse.’

If they’d been tampering with animal cages, they probably deserved a boot, or a psychiatric assessment, at least. ‘I’d hazard a guess they were law students,’ I said. ‘Are you able to give me a good description of them?’

‘We can do better than that,’ said a man with some rather interesting facial piercings and an Eastern European accent. ‘We have pictures.’ He held up a digital camera.

Someone had had a brainwave. The advantages of modern technology. ‘That will certainly make life easier. I’ll have to take the memory card with me, but we’ll return it as soon as we’ve copied the files.’

I felt a tap on my shoulder and turned to see Smithy’s face; it was scrunched up into a perplexed expression.

‘Detective Smith – Terry Bennett,’ I said, and they both gave a cursory ‘Gidday’, or mumble to that effect, before Smithy gestured back towards the crowd.

‘We’ve got a little problem with the guy in the cage.’

‘What kind of a problem?’ I asked.

‘An immovable one. Not only has he padlocked himself in, but he’s also driven pegs down and secured the cage from the inside. I can’t shift it.’

‘Oh, bloody marvellous,’ Terry Bennett boomed. ‘Now he’s stuck there for God knows how long. I’ve got a show tonight. How the hell do I get the crowds in with that git stuck there, yelling at everyone?’

‘We could get a crane in and pull him up,’ Smithy suggested.

It was an idea, but one that would provide the perfect fodder for the television crews waiting for just such a spectacle. I could imagine it headlining the evening news, with plenty of choice sound bites coming from the bloke dangling in mid-air. No, there had to be a better way.

‘Well,’ I said as I looked up at the big top. ‘There’s no show without the star.’ I turned back to the circus guys. ‘Do you have any tarpaulins or a marquee that would fit over that cage?’

Terry Bennett’s face broke into a grin – probably for the first time that day. Yep, definitely a smoker and in need of some serious dental work.

‘I’m sure we can find something for the job,’ he said, and he and two of his cohorts disappeared around the back of the enormous tent.

‘Let’s go deal with the rest of the protesters,’ I said to Smithy, setting off towards the action. I thought it very quaint how he liked to let me take control, even though we both knew damned well who called the shots.

The protesters group seemed to number around twenty, but the spectators had grown to more than fifty and had inched their way closer to the action. I went for the spectators first. It was moments like these I wished I had my police blues on again, instead of the civvies – black trousers and white shirt – that had become my substitute. People knew how to behave around a uniform.

‘Police,’ I yelled, trying to be heard above the general chatter and hoping like hell they could see me. ‘Okay, everyone, I’m going to have to ask you all to move back to the roadside. Come on, move back please, people. Clear the space here, thank you.’

Smithy worked the group over to the right of me, and I was relieved when they immediately obliged. It was easier than herding sheep. The only exception was the camera crew who steadfastly refused to budge. Surprise.

I lowered my voice and spoke directly to the reporter, who I recognised from the six o’clock news. ‘Come on guys, move back please. There’s not going to be anything interesting or newsworthy here. Let us get on with our jobs. If you move by the trees over there, you’ll be out of our way and you’ll still be able to see if you want to.’

‘Can you make a comment on the actions of the protesters, and how you will remove them?’ the reporter asked, pointing a fluffy microphone in my direction. It brought back memories. At least I wasn’t wearing my pyjamas this time.

‘I’m sorry. You know I can’t comment right now. But thank you for cooperating and moving back.’ Politeness recorded on camera won the day, and they edged towards the tree line.

Next were the protesters. I didn’t think they would be as amenable.

‘Okay, the show is over. I’m going to have to ask you to move away now.’

‘Sod off, pigs. We’ve got just as much right to be here as you have,’ yelled the man in the cage via his megaphone. I was only a metre from him, so the amplification was hardly necessary. The charming namecalling must have embarrassed some of the others, as a well-dressed lady with greying hair quickly stepped up and addressed us while gesturing at Cage Guy to stop.

‘I’m sorry, officers,’ she said with impeccable enunciation, ‘but this is a public place, so we are perfectly entitled to exercise our right to protest. This circus exploits animals for its financial gain. It doesn’t care for them humanely or to any recognised standards. It’s unethical and we—’

‘I’m sorry, ma’am,’ I interrupted, ‘but as this circus has a council permit to occupy this public space for the purposes of its show, it is temporarily deemed by law to be a private place and therefore you are trespassing and can be asked to leave. If you choose not to leave quietly, you can be charged with trespass, and then you can explain your purpose to a judge.’ This news was greeted with much muttering and many confused looks from the protesters. Then several of them spotted the small tent, fully erected and being carried along by four of the circus men.

‘What on earth…’ murmured the woman.

‘Look, come on, now. It’s time to move along, please. I don’t want to have to start taking your names.’ Most of them moved back ten metres or so, but several, including the woman and gorilla man, stayed to see what was happening with the tent.

It didn’t take long for Cage Guy to figure out what was about to happen. He yelled at the top of his lungs, this time without the megaphone: ‘You can’t put me in that. That’s wrongful imprisonment.’ I wondered if he was in the same law class as the university students.

‘Come on, guys,’ I said to the circus men, as I gestured to them to straighten up, so they could position the tent gently over the cage. It was a perfect fit, with about a foot clearance each side. Nice and claustrophobic. Cage Man screamed the whole time the tent was being lowered. Great, now we had a talking marquee.

His ‘You can’t do this to me’ scream was echoed by the ‘You can’t do that to him’ cries from the protesters. One or two tried to shove me aside and stop the tent’s progress, but slunk back when I yelled, ‘That’s assault of a police officer,’ and Smithy struck a pose that would have intimidated Mike Tyson.

‘This is illegal detainment. You haven’t arrested me. I’ll have you for wrongful imprisonment,’ came the voice from inside the tent. It had developed a distinct whine.

I yelled loud enough to make myself heard by all concerned: ‘Well, sir. The tent is not locked. It is merely there to shelter you. We were concerned about your safety and comfort on such a sunny day.’ The sunshine certainly was in abundance; the temperature, however, did not match it. A bank of cloud rolling in from the south indicated the Dunedin weather was going to be its usual schizophrenic self. But that was by the by. I paused for effect before continuing. ‘You are not being detained,’ I said. ‘In fact, you are free to leave at any time you wish.’

Several expletives erupted from within the tent, but I could tell from the tone of his voice that Cage Man realised he’d been outmanoeuvred. The circus crew were pissing themselves, and it was all I could do not to snigger. The remaining protesters gave up and had the grace to smile as they retreated further still.

‘Nice one, Sam,’ Smithy said, a big grin plastered across his face. ‘I didn’t know about the permit and trespass thing.’

‘Neither did I,’ I whispered. ‘But it sounded good at the time.’

2

This was not how I’d envisaged spending my Saturday morning. Dunedin had abandoned yesterday’s sunshine in favour of a mantle of mist and drizzle that hung around like some sullen teenager. A fair amount had attached itself to me. The gloomy atmosphere made the vision before me all the more miserable.

She was discovered by a resident from the units on the far side of the Leith, who’d come over to the river’s edge to call her cat in for breakfast. Instead of kitty, the old dear had been shocked to see a body in the water near the other bank. She’d been so shaken, she’d needed medical treatment; the ambulance was still in attendance.

So here I was, on a riverbank, plagued by a sense of déjà vu – the body of a young woman face down in the water before me, like a piece of flotsam. This time there was no doubt as to foul play. Her hands, floating in front of her, were bound by a clear plastic tie. The silver tape covering her mouth extended around the back of her head like some warped, glitzy headband from which her long dark hair fanned out across the water.

I had to push aside my instinct to wade in and drag her out. After my initial, futile check for signs of life, my role was to stand guard and wait for the forensic experts and scene-of-crime officers, or SOCOs as we called them. It was not the role of a small-bit trainee detective to examine anything; any interference on my part would certainly not be appreciated – my boss had made that patently clear. In fact, I wouldn’t normally be allowed to be the first so near a crime scene, but someone had to keep watch and today that someone was me.

I filled the time by making a visual sweep of the scene from my appointed position, but I dared not move for fear of disturbing any potential evidence. I barely dared breathe.

I stood in a small, grassed clearing with the river before me and at my back a steep hillside clad with native bush – flaxes, kowhai and ngaio. The clearing was at the end of a narrow path that ran down from the main walkway, which itself ran around the base of the hill, following the Water of Leith from the Botanic Garden to Gore Place, before leading out on to Dundas Street. I shuddered. The Botanic Garden was one of my havens in Dunedin. Twenty-eight undulating hectares of picturesque solitude only minutes from home. Two days ago, I’d jogged along the walkway; it was a regular on my running circuits, and in all the months I’d been here, I hadn’t realised this path existed. I’d noticed the big, spidery tree at its entrance, where Smithy now stood guard with a bit more shelter than I had, but I’d never registered the path itself. The main walkway was high above and behind me, well obscured by the dense bush and trees. The clearing and the water would be invisible from up there, although voices would probably carry.

In front of me the Leith gently wended its way over rocks and past the banks. It was fairly shallow at this point and was open, unlike in other parts of the garden, where it was confined by the steep concrete walls of the flood-control channels. It would have been a pretty spot if it weren’t for the body. A large boulder jutted out into the water, preventing her from drifting away with the current, helped by what I imagined was a stack of wet books in her backpack: a badge of studenthood that now only served to weigh her down. With the modern student, though, the backpack was just as likely to hold a laptop.

Another nearby boulder had traces of blood and tissue on it, which pretty much confirmed this as the site of the murder, as did the skid or drag marks in the grass. The blood traces were another reason why I felt so wet and miserable. The drizzle had threatened to wash the remaining blood away, so in desperation I’d covered it with my jacket rather than risk losing valuable evidence. I figured potential contamination from one easily identifiable person was preferable to nature erasing any clues. I still hoped they wouldn’t rap me over the knuckles for it, though.

It was a risky site to stage a murder. Whereas this side of the river was well obscured, several flats and houses backed on to the other bank – including Mrs Franklin’s, the old lady who I could now see being stretchered off to the ambulance. So the killer or killers must have felt certain they wouldn’t have an audience when they murdered this young woman. And the only real chance of that happening would have been under cover of darkness. But how would you get someone down here in the dark without physically dragging them? There was no visible evidence of that. The only place the grass was disturbed was near the bloodied rock. I shuddered again.

They must have coerced her somehow. Either that, or they knew her, and she came down here with them willingly, perhaps for a smoke, a chat or a snog. The murder had to be premeditated, though, that much I was sure of. Most people didn’t walk around with long plastic cable ties and duct tape in their pockets. Well, the people I knew didn’t.

However the killer managed to get her down here, the end result was dumped before me. God, what a waste. Even in this condition, I could tell she was pretty. Sometime soon her parents and loved ones would receive the call that would wrench their world apart. I bit my lip to try and force back the tears that sprang into my eyes. Sometimes, I really did wonder if I was cut out for this job.

Man, I wanted to be out of here. I wasn’t exactly comfortable around dead people – especially young, violently killed, female dead people: they were too similar to what happened in Mataura. But that wasn’t the only reason I wanted to leave: all of this cold, damp air and running water had left me desperate for the loo. I jiggled from foot to foot in an attempt to find a position that was almost comfortable.

Failed.

I badly needed to be relieved.

3

Warmth and dry clothes were what I was looking for after the bone-numbing chill caused by standing in the rain and having to look at that bedraggled body. I had planned a quick dash home to change before going back to work, but it didn’t quite pan out that way. First I’d had to park half a mile away from home, at Roslyn Village, as some dick-head had their car parked outside our gate and left it marooned there for the last two weeks, selfish bastard. Then, when I headed back to work and when I got to my usual parking area down behind the old railway station, someone else had nabbed my spot and the rest of the place was chocka, courtesy of the Saturday morning farmers’ market. It had taken me two drives around the block and another ten flaming minutes before I finally found a place to park, somewhere near Christchurch. By the time I’d walked to the police station I was wet and cold again, so what with that and the morning’s events, I was about ready to rip the throat out of the next person to annoy me.

‘Grumpy alert: be nice,’ I said to Smithy as he sat down next to me at the back of the briefing room.

‘You didn’t need to warn me – you’re radiating nasty vibes. Why do you think no one else is sitting here?’

He had a point.

‘I thought you’d gone home to get dry,’ he said. My fingers twitched for his jugular.

The room was filling up with police and CIB. Many had been on duty at the rugby the previous night and had been called in from home for the murder enquiry. The Otago Highlanders had done the unthinkable and won the match, which resulted in a fair amount of carousing by the fans, so it had been a busy night and there were several hung-over bodies warming the cells downstairs. There was an awful lot of yawning and eye-rubbing going on upstairs, too. It was only eleven o’clock in the morning and, considering the victim had been discovered at a quarter past eight, the police behemoth had proved it could move pretty quickly when it needed to.

Some initial murder-scene photographs had been stuck with magnets to the whiteboard at the front of the room. I was too far back to distinguish any detail, but I didn’t need photos – the vision was burned into my brain. At this moment, the SOCOs were down at the Leith, doing their thing, and the forensic experts from Environmental Science & Research were on their way from Christchurch. Courtesy of her student ID card, we knew the identity of our young victim, so it was game on.

This was the first murder investigation here since I’d been accepted for detective training and quit the bright lights of Mataura for the great metropolis of Dunedin. This said something about the serious-crime rate in the city, as I’d already been here for half a year.

I was one of those in-between creatures – not a detective, nor a constable; a hybrid adrift in this esteemed institution. I had just come out of my six-month trial and was officially a detective constable. This had all happened rather more quickly than expected – people could wait years before becoming a trainee detective – but the powers that be had smiled upon me and here I was. Others were not so thrilled about my promotion through the ranks. So right now I was wondering what sort of a role I’d get in this investigation – not only because I was a newbie, but also because the officer in charge of the investigation was Detective Inspector Greg Johns. I hadn’t exactly endeared myself to him during my Mataura days. It was probably when I told him he could go rot in hell that did it. Or was it when I informed him he was a hack with a paper degree who couldn’t solve a mystery if the answer was tattooed across his forehead? I’d also insulted his favourite poncy briefcase. That was most likely the clincher. The fact I’d solved the murder of Gaby Knowes didn’t seem to make a jot of difference to him. I always got the crap jobs.

The Saturday-morning buzz simmered down as DI Johns took centre stage for the day’s briefing. His body language told me he was entirely comfortable with – no, make that relishing his role as the focus of attention. Some people were just like that.

‘Right people, let’s get things under way.’ The DI clapped his hands like we were a bunch of errant schoolchildren. ‘This meeting is going to be short. We’re not going to waste time in here. I want everyone out there, on the streets. The officers in charge are on the board. Everyone else: Detective Sergeant Gibbs will give you your brief and tell you where you’ll be assigned.’ The DI moved over to the board with the photos. ‘The victim is Rose-Marie Bateman. She’s twenty-three; a student at the university. Her body was discovered in the Water of Leith, near the walkway from Gore Place to the Botanic Garden, at eight-fifteen this morning by a resident in the area. SOCOs are at the site now and ESR on the way.’ Bang. Bang. Bang. A bullet-point presentation. He wasn’t one for superfluous detail.

‘The investigation will be called Operation Sparrow.’

I cringed. One thing that irked me was the police’s little habit of naming operations after birds. I supposed it made it easier than having to talk about the investigation into the murder of so-and-so – but birds? And ‘Sparrow’? Sparrows were boring – drab, brown, puny things. Rose-Marie was young and pretty. Surely they could have come up with something a little more appropriate?

‘The body is still in situ and we won’t be able to confirm anything until a post-mortem is carried out, but indications are the murder took place last night. The victim’s hands were restrained with a plastic cable tie and her mouth was taped. She suffered blunt-force trauma to the head, most likely from being banged against a rock, but she probably died by drowning. Her clothing was intact and there doesn’t appear to have been any sexual assault.’

I studied the faces around me. Put like that, in shopping-list fashion, it didn’t seem to make much impression on them. But I had seen it. I had seen her in the cold, waxen flesh, murdered and discarded, bedraggled and pitiful. The chill settled back into my bones, and I couldn’t stop a shudder. The only face that mirrored my own distaste was Smithy’s. He’d borne witness too. He felt my stare and gave me a gentle thump on the leg. It induced a small smile. I returned my attention to the DI.

‘As the attack happened so close to the university, we will start our investigations there. She appears to have been walking home from the university to her flat in Opoho Road. There doesn’t seem to have been much of a struggle, so it is likely she knew her attacker. She’ll have had hundreds of classmates and university associates for us to work through. Of course, we’ll be looking at her boyfriend, flatmates and friends too. Her family are from out of town – Napier. So altogether there are a hell of a lot of people to talk to and eliminate. Also, the Botanic Garden is a busy place. Someone must have seen something. We need to talk to every person who walked through there last night. Let’s get busy, people.’

The room jumped into movement. Voices buzzed, papers rustled, people got busy, as ordered. Everyone else seemed to know their place, whereas I felt a bit like a spare nut rattling around loose in the engine. When I was in Mataura, I was it: sole-charge police officer. So I got to talk to everyone – do the interviews, analyse the information. I was the thin blue line. I only hoped I’d get a chance here.

How would I handle this investigation? If I was calling the shots I’d start with the boyfriend, then work my way through the flatmates. As stereotypical as it seemed, statistics told it was, as often as not, the boyfriend. Maybe they had problems, couldn’t talk through them, so he decided to take other measures. Then there were the flatmates. They could’ve fallen out over burnt dinners or the electricity bill. Perhaps she’d borrowed someone’s hairdryer and accidentally blown it up; eaten someone else’s yoghurt. Stranger things had happened.

We were at the back of the room and Alan Gibbs, one of the senior officers, only now worked his way along the row. He handed me a piece of paper, and said, ‘For you. From the boss.’

‘Thanks,’ I said, as he moved on to talk to someone else. Please let it be something front-line. Please. I unfolded the page.

‘Oh crap,’ I murmured to myself. It was a bit too loud, though, as Smithy leaned over to look at the note.

‘Lucky you,’ he said, with a grin.

‘Well, I wouldn’t get too cocky if I were you,’ I said. ‘You know who you always end up with – me.’

‘Not this time, sunshine, I’m with suspects. Looks like you’re flying solo today. You must have really pissed that man off.’

‘Don’t I know it?’

There would have to be hundreds of places in Dunedin you could buy a plastic tie, and it was my job to find where the one used in the murder was purchased. That’s assuming it was even bought in Dunedin. A mass-produced, bog-standard, come-in-a-pack-of-a-hundred, non-identifiable, indistinguishable plastic bloody tie. Normally, ESR did this kind of leg work, not CIB. They had all the flash databases and extensive files to compare things, from brands of carpets to tyres. This was their territory. It wasn’t a very subtle backhand. To add further insult to injury, I was directly answerable to the DI.

No intermediary, no buffer.

Bloody marvellous.

4

The man standing behind the counter looked at me like I was wearing a Crunchy the Clown outfit or had something nasty stuck to my face. Having made five similar requests at five similar stores, it was a look I’d become familiar with and was well and truly over.

‘You want to know if we can identify everyone who has bought plastic cable ties in the last week?’ He was a little more forthright than the others and laughed openly. ‘What do you think we do all day?’

Eat donuts, I thought, from the look of him.

‘No, of course not. Don’t be silly. We know you can’t identify each individual.’ I tried to diffuse the situation. Difficult, when I was sick of it and felt I was pushing shit uphill with a rake. ‘But you are computerised, so you’d be able to let us know the dates of sales and how they were paid for.’

‘Huh.’ He grunted. ‘To a point. I could look up the pre-packs, but the individual ties go under miscellaneous.’

‘What about how they were paid for? Does the computer record debit- or credit-card details for each sale?’

He gave me that look again. I was tempted to wipe it off his face.

‘This is Dunedin, love, not a US TV show, where you can waltz in and, hey presto, every little detail is nicely recorded for you. So, no, mine doesn’t. The systems are separate.’ The last four words he said real slow.

My fists clenched tighter. Condescension and a ‘love’. I cursed the fact Smithy was off doing the interesting stuff while I was flying solo with the plebs. I took a deep breath and counted to ten in my head, in order not to lose the shred of control I had left. I reminded myself that, for the privilege of wearing that bright-yellow shirt to work each day, he was probably paid bugger all. There was some justice in the world.

I’d already checked out the stock on the shelves before approaching Mr Attitude, and found some very long ties that matched the one used in the murder. The tie used to bind Rose-Marie Bateman’s hands was still attached to her, so all I had for comparison was a measurement and a grisly photo. One small satisfaction was that the discovery of possible candidates meant I had the pleasure of relieving the man of some of his stock.

‘I’ll need to take some samples of those ties for the investigation.’

‘Well, I hope you’re going to pay for them.’

Bloody hell. Here we were, working on the murder of a young woman, and he was worried about a few cents for some crappy bits of plastic. It must have shown on my face as he dropped his eyes and had the decency to look abashed.

‘I’ll give you a requisition form, so you need not worry about losing any money. We would hate to inconvenience you in any way.’

‘Okay, that’s fine,’ he mumbled.

His discomfort gave me a small stab of pleasure. I turned and looked towards the area where the plastic ties were shelved. There was a surveillance camera nearby that possibly covered that section. I turned back to the manager.

‘Your security cameras. Are they constantly recording?’

‘Yes.’

‘What about that one there.’ I pointed to the front corner. ‘How far back would the footage go? Would it be a week or more?’

He assumed that sheepish look again. ‘No, it wouldn’t go back quite that long.’

‘What, only a few days?’

‘Well, no.’

‘What then?’

‘We record over the same file each day.’

I was about to ask why the hell they bothered with it, then? But what was the point? Life was too short. It was almost four o’clock; he’d be counting down the seconds until closing and yesterday’s recording was probably overwritten.

‘Can I get you to at least print out the sales of cable ties going back a week, then?’

‘Yeah, I can do that, but not straight away. It takes a while. These things aren’t instant, you know.’

‘That would be appreciated,’ I said, forcing myself to be polite. ‘Can I pick them up in the morning?’

‘Yeah, fine.’

5

‘Well that was a colossal waste of a day,’ I said, plonking my butt on to a chair at the kitchen table. One of the joys of being adopted into this household was the insistence, when timetables and schedules allowed, of family dinners together, with civilised conversation over good food and, more often than not, wine. The reason I’d been adopted was Maggie, my former Mataura flatmate and current fellow boarder who, fortunately for us both, had very amenable relatives. Her Aunty Jude was shaking up, cocktail-style, what I assume was some kind of dressing for the salad. Her concoctions were always delectable, and she had a vast collection of cookbooks on hand if she ever lacked inspiration. My nose was being wooed by the aroma of roasted chicken with a hint of what I thought was smoked paprika, and my stomach gurgled in anticipation. Uncle Phil was busy consulting the oracle that was the wine fridge – yes, this household could boast its very own, purpose-built, wine fridge. God, I loved Maggie’s family. Although, if I was going to be picky, their commitment to culinary delights didn’t extend to a dedicated chocolate fridge.

‘I thought you guys would have been flat out on the job today,’ Maggie said as she placed the salt and pepper grinders in the centre of the table. ‘I heard there were nasty things going on around the gardens.’

‘Nasty isn’t the half of it. Urghhh,’ I shuddered. ‘It brought back all the wrong kind of memories. What is it with me and having to deal with dead young women in rivers?’

‘Well, you do seem to get more than your fair share. Any more and you’d call it a speciality,’ she said as she slid on to the neighbouring seat. Maggie had been my flatmate back in our Mataura days and like me had decided to upgrade to first class and Dunedin after our lives in the little town went up in smoke. Once we’d gotten back to a more stable financial situation we’d probably look for a flat again, but for now we were both enjoying mates’ rates at her aunt’s.

‘I can think of better specialities. Not that I got to specialise in anything today other than running around after the minor stuff, while everyone else got the good jobs. If this had been Mataura, I would have been the one interviewing the poor girl’s boyfriend or flatmates, or anyone for that matter. God, I’d have even settled for talking to her postman, not getting the crap jobs, as usual.’ My voice sounded whiny. Not good. I promised myself to watch that.

‘Well you are the junior, so to speak, so you’re at the bottom of the pecking order. What do you expect? You should be glad you’re not sweeping floors and making the coffee,’ she said, with a cheeky grin.

‘I do make the coffee.’

‘Oops.’ She gave me a conciliatory pat on the arm.

‘Ah, but you’re probably right,’ I said, this time without the whine. Maggie had far too level a head on her sometimes. If I’d been inclined to believe in reincarnation, she would have been one of those wise old women in another life – the ones with flowing robes, manes of black hair streaked with white and deeply lined faces oozing serenity. Maggs was the modern version; she had the serenity vibe, but was a stylish young thing who could throw the most unlikely garments together and look effortlessly cool. She was also the only person I’d ever met who could make a brown and yellow zip-front tracksuit top look good. Cow. My style, if you could call it that, was more frenetic conservative.

‘You know I can’t help but think I get lumbered with the crud because DI Johns has got his little grudge. Sometimes I wonder if I’d have been better off sticking with being constable of a shithole little town, oops, sorry about the language.’ I looked up at Aunty Jude. ‘At least in Mataura I made a difference rather than getting delusions of grandeur in the city. Here I feel like, well, anonymous.’

Maggie laughed. The sound echoed from two other locations in the room. ‘For a start, you’re anything but anonymous, and secondly, I believe you did rather insult the man, so he’s perfectly entitled to hold a grudge. And, most importantly, I seem to recall some of the locals in that, quote, “shithole little town” you’re so fondly reminiscing about blew up your house and tried to have you killed – and me, for that matter. Got the scars to prove it. In fact, you should come with a public health warning.’