7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

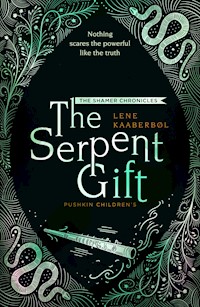

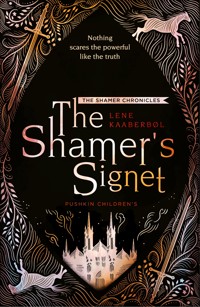

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Children's Books

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

The second book in the thrilling fantasy adventure series, The Shamer Chronicles Dina has the Shamer's Gift - one look into her eyes, and none can mask their guilt or hide their shame. Now even her brother, Davin, no longer dares to meet her gaze. He burns with a desire to take up the sword and avenge the crimes committed against his family. But these are treacherous times and Dina's life is in terrible danger. Kidnapped by the corrupt Valdracu, she is forced to use her gift as a weapon. And Davin becomes her only hope of escape... An award-winning and highly acclaimed writer of fantasy, Lene Kaaberbøl was born in 1960, grew up in the Danish countryside and had her first book published at the age of 15. Since then she has written more than 30 books for children and young adults. Lene's huge international breakthrough came with The Shamer Chronicles, which is published in more than 25 countries selling over a million copies worldwide.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR

The Shamer Chronicles

‘An absorbing and fast-paced fantasy/mystery bursting with action and intrigue. The only question is: when will the next one come out?’

BULLETIN OF THE CENTER FOR CHILDREN’S BOOKS

‘The series as a whole is in good standing alongside Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy and C. S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia’

BOOKLIST, STARRED REVIEW

‘[A] fine novel … The term ‘page-turner’ is often used, but not always justified. It is deserved here, tenfold. I really, really couldn’t put the book down’

SCHOOL LIBRARIAN

‘Full of passion’

JULIA ECCLESHARE,GUARDIAN

‘I gobbled it up!’

TAMORA PIERCE, AUTHOR OFTHE SONG OF THE LIONESS

‘The most original new fiction of this kind … equally appealing to boys. Here be dragons, sorcery and battles’

THE TIMES

‘Spiced with likable characters and an intriguing new magical ability – eagerly awaiting volume two’

KIRKUS

‘This novel stands on its own and offers a satisfying conclusion even as it provides an intriguing setting and mythology for future adventures’

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

‘Classic adventure fantasy, with the right combination of personalities, power, intrigue, and dragons – it will prove to be a sure hit’

VOYA

CONTENTS

DINA

The Child Peddler

Among heather-grown slopes nested three low stone houses. A narrow cart track, not much more than a path, swerved to pass quite near, but there was little reason to halt here, unless one was very fond of heather, open sky, yew trees, and grazing sheep.

Nevertheless, a peddler’s cart stood on the patch of packed dirt between the houses, and in the stonewalled fields the sheep had company—two mules and four horses rested, heads low and tails swishing, dozing in the early evening sun. And now we were making our way down the hill, my mother and I, and Callan Kensie. Most of the sheep stood stock-still, watching us suspiciously, and I could almost feel their puzzlement. Probably they had never seen so many strangers at Harral’s Place before.

The sun hung huge and orange just above the ridge. The day had been warm and almost summery, and the air was still pleasant. Next to the peddler’s wagon, three men were playing cards, using a beer barrel for a table. A pile of round flatbreads, three mugs of beer, and a fat, darkly gleaming sausage competed for space on the barrel top. It looked like something one might see outside any village inn on a breezy spring evening, until one noticed the leg iron that kept the peddler’s ankle chained to his own wagon wheel.

The peddler carved himself a fat slice of sausage and slid the rest of it across the barrel top toward the two men who were supposed to be guarding him.

“Here,” he said. “Eat. A good game of cards can make a hole in a man’s belly.”

“Never mind the belly,” grumbled one of the guards. “Losing four copper marks and a perfectly good knife makes a sizable hole in a man’s pocket!” But his complaint was good-natured, and he accepted the sausage.

At that moment, one of the mules brayed earsplittingly, and the guards looked up and caught sight of us. They leaped to their feet, and one of them hastily swept the cards off the barrel, as if we had caught them doing something disgraceful. But I knew how they felt. It was hard to act harsh and commanding toward a man once you started drinking his beer. And it was difficult to believe that there was any truth to the accusations that had been made against the cheerful little peddler. We knew him. He had come by our village often enough, and everyone enjoyed his visits. He was never without a joke or a good story, and he had a chuckling laugh and so many crow’s feet that one could hardly see his eyes when he smiled. His eyebrows looked like two fat black slugs, except that they moved more quickly—one of them would shoot up questioningly at every other word. No, I thought, he was hardly guilty of anything more serious than cheating a bit on his measures. The boys must have run away, just like he said they had.

“Medama,” said one guard, bowing in my mother’s direction. He eyed me dubiously—just how polite did one have to be to an eleven-year-old girl? He settled for another bow, slightly less deep. “Medamina.” After all, I was the Shamer’s daughter. The third person in our party, Callan Kensie, received not a bow, but a measured nod, of the kind men give each other when there is respect between them, but not necessarily friendship. “Kensie. I thought you were guarding caravans down in the Lowlands.”

Callan returned the man’s nod, in exactly the same manner. “Well met, Laclan. But no. I have other duties now.”

“So. The Kensie clan takes good care of their Shamer, I see.” The guard’s eyes rested for a moment on Callan’s shoulders, very wide and knotted with the muscles a man gets from wielding a sword every day. Like most people, he avoided looking too hard at my mother. If one did not already know, the Shamer’s signet resting on her breast, in clear view, provided ample warning: a heavy round pewter circle, enameled in white and black to look like an eye. I had one almost exactly like it, but with blue instead of black, because I was still only my mother’s apprentice. Anyone who saw the signet would look away—or pay the price.

The peddler had also risen. “Well met,” he said, grinning. “And none too soon. The company has been pleasant, but I had hoped to reach Baur Laclan before dark.”

There was no trace of anxiety in his manner, and I grew even more convinced of his innocence. Not many people await the Shamer’s call with such steadiness. He bowed briefly to my mother and then to me. “Well met,” he repeated. “But what a pity to send two ladies on such a long journey, and for no reason.”

My mother raised her head and glanced briefly at the peddler.

“Let us hope there is no reason,” she said, not loudly, nor in any threatening tone of voice. Yet for the first time the grin on the little man’s face started slipping, and he raised his hand to his mouth involuntarily, as if to prevent more words from escaping. But he recovered quite quickly.

“May I offer some refreshment after your long ride? Good beer? A bite to eat?”

“Thank you, no,” said my mother politely. “I have a duty. That must come first.”

She dismounted, graceful still despite the long ride. Falk, our black gelding, nosed her hopefully, wanting to be rid of his bridle, but she handed the reins to Callan. I got down off the small tough Highlander pony I had borrowed—less gracefully, I’m afraid. I get less practice. Callan loosened the girths to allow the horses to breathe freely, but he made no move to unsaddle them. He clearly did not expect a long stay.

“What is your name, peddler?” my mother asked, quietly still, with no hint of anger or threat.

“Hanibal Laclan Castor, at the lady’s service,” he said, delivering an unexpectedly smooth bow.

My mother pushed back the hood of her cloak and looked at him. “My name is Melussina Tonerre, and I have been tasked to look at you with a Shamer’s eyes, and speak to you with a Shamer’s voice. Hanibal Laclan Castor, look at me!”

The peddler started, as if someone had turned his own long skinner’s whip on him. The tendons in his neck stood out tightly, like the strings on a lute. Much against his will, he raised his head to meet my mother’s gaze. For a while, the two of them stood locked in complete silence. Sweat beaded the peddler’s forehead, but my mother’s face remained as expressionless as a mask of stone. All at once, the peddler’s legs buckled, and he dropped to his knees in front of her. Still she held his gaze. He knotted his fists so tightly that his nails bit into the palms, and a few drops of blood appeared between the clenched fingers on one hand. But however much he wanted to, he could not look away.

“Release me, Medama,” he finally begged, choking. “Be merciful. Let me go!”

“Tell them what you have done,” she said. “Tell them, and let them witness it. Then I shall release you.”

“Medama… I have merely done a bit of business—”

“Tell them. Tell them exactly what you mean by doing a bit of business, Hanibal Laclan Castor!” For the first time, emotion crept into my mother’s voice: a seething contempt that made the little peddler shrink and become visibly smaller.

“Two boys,” the peddler breathed, his voice hardly more than a whisper. “I took two boys into my service. It was an act of human kindness, they were both orphans…. No one in the village wanted them…. I treated them well, fed them properly, and saw to it that they were decently clothed. They had never been better off in their lives!” The last words came loudly and defiantly, a final defense. But they did not impress my mother.

“Tell us what happened later. How kindly you then acted.”

“The winter was a hard one. I lost an entire load of seed corn when we were snowlocked at Sagisloc. It sprouted and fermented, corn worth sixty silver marks, completely useless! And the boys… one of them was all right, a soft and biddable lad. Not very strong, though. But the other! Trouble, he was, always trouble, from the very day I laid eyes on him. One time he pinched seven needles from my stock and sold them on his own. And spent the profits on cake and hot cider! Gave him a beating for that. Of course I did. But it was useless. He only got worse. Always contrary, always disobedient. If I asked him to unhitch the mules, he would scowl and tell me to do it myself. Send him for firewood? He would be gone for hours, and I would see neither hair nor hide of him until the fire had been long lit and the soup cooked. What was I to do? Sooner or later he’d have scarpered, and there I’d be, with nothing to show for all the money I’d spent on food and clothing for that lout. No doubt he would have taken the other one with him, they were such little pals, the two of them.”

The peddler’s flow of words came to a halt.

“And then?” My mother’s voice prodded him onward. “What did you do then?”

“Then… I found them other employment.”

“Where?”

“With a real gentleman—cousin to Drakan himself, the Dragon Lord at Dunark. Not such a bad fate, I’d say—serving a lord. If they play their cards right, they may end up with a knighthood! The Dragon Lord looks not on birth and reputation, they say, but on whether a man serves him well and true.”

“And the price, peddler. Tell us your reward.”

“There were my expenses,” the peddler moaned. “Had to get a bit of my own back, didn’t I? What’s so bad about that?”

“How much, peddler?” The question came like a lash, and the peddler opened his mouth to answer, unable to stop himself.

“Fifteen silver marks for the runt, and twenty-three for the lout. He was tall and strong for his age.”

The guards who had drunk his beer and eaten his food now looked as if they regretted it. One of them spat, to clear the taste from his mouth. But my mother had not finished with the man.

“And it was then you discovered that this was a profitable line of business, wasn’t it? Tell us, so that the witnesses may hear. How many more? How many more children did you sell to Drakan?”

It seemed that for the first time the peddler looked beyond defenses and excuses. His wrinkled face was pale now, the eyes lightless like charcoal. Only now, trapped in the merciless mirror that the Shamer had created for him, did he see himself clearly. His voice cracked.

“Nineteen,” he said, hoarse with shame, “including the first two.”

“The outcasts. The orphans. The rebels and the crazies, the slow-witted and the crippled. The ones the villages are eager to be rid of. Do you really think, Hanibal Laclan Castor, that Drakan buys them so that he can make knights out of them?”

Tears trickled among the crow’s feet. “Let me go. Medama, I humbly beg, let me be…. I’m so ashamed. By the Holy Saint Magda, I’m so ashamed.”

“Witnesses. You have heard this man’s confession. Have I done my duty?”

“Shamer, we have heard his words. You have done your duty,” said one guard slowly and formally, glancing contemptuously at the weeping man crouched at her feet.

My mother closed her eyes.

“What will ye do to the little bastard?” Callan asked, not even deigning to look at the peddler.

“He is a Laclan,” said one of the guards. “Through his grandfather only, but still… the Laclan clan must judge him. We’ll stay here overnight and bring him to Baur Laclan in the morning.”

“To sell people… to sell children…” Callan’s voice was thick with disgust. “I hope he hangs!”

“Likely so,” said the guard drily. “Helena Laclan is not a soft woman, and she has children of her own. And grandchildren.”

Callan tightened the girths and then offered his hand to my mother, who had sunk down on one of the stone walls, looking completely exhausted.

“Medama Tonerre? Will ye ride? The sky is clear and we’ll have a full moon to see by. And I’ve no liking for his company.” He jerked his head toward the peddler.

Mama raised her head, but politely refrained from looking straight at him. “Yes. Yes, let’s ride, Callan.” She accepted his hand, but was too proud to let herself be lifted into the saddle. She made it on her own, but we could all see that she was shivering from strain and exhaustion. No doubt it would have been more sensible to stay the night, but I bit my lip and did not speak until we had crossed the first ridge and were out of sight of the guards and their sniffling prisoner.

“Was it bad?” I asked cautiously. She looked as if she was in no fit state to sit a horse.

The same thought had occurred to Callan. “Are ye fit to ride, Medama?” he asked. “We could make camp….”

She shook her head. “I’ll be fine. But it’s… Callan, I see what he sees. When I look into his soul and his memory… to me it’s not just a number. Nineteen. Nineteen children. I’ve seen their faces. Every one of them. And now… he has bought them. Bought them and paid for them, as though they were animals. What do you think he is going to use them for?”

None of us had an answer. But as we followed the track below the heather hills and the darkness grew close around us, I heard Callan mutter once more: “I hope the little bastard hangs.”

He didn’t. A couple of days later, a sheepish-looking Laclan rider came to tell us that the little peddler had carved through the spoke of the wagon wheel they had chained him to, using the knife he had won at cards. He had run off, and Laclan had declared him an outlaw in the Highlands, denying him his name and his clan rights from now on till the end of time. Anyone who saw him could now kill him freely, without fearing Laclan’s wrath. But no one had seen him since.

DAVIN

The Sword

Carefully, I freed my new sword from its hiding place in the thatched roof of the sheep shed. It was not what you’d call shiny bright—not yet. A blackish gray color, it was, thick and heavy, and without much edge or point. It was little more than a flat iron bar at the moment. But Callan had promised to help me file and sharpen it, and in my mind I could see it already, the way it would be: a slim, bright weapon, sharp and deadly. A weapon suitable for a man.

It had cost me two of my good shirts—I now had only one left—and all of the seven coppers I had earned last summer, helping out at the mill in Birches. It was well worth the price, I thought. As long as my mother didn’t find out about the shirts. Or at least not right away…

“Davin, will you please take the scraps out for the goats?”

I don’t know how she does it. I really don’t. But anytime I’m about to do something remotely fun or exciting, every time I’m about to do something she might not like, she can sense it from a distance of at least three miles, and instantly sticks me with some boring task I have to do instead. Feed the goats. Dina could feed the goats. Melli could feed the goats, and she was only five. She didn’t need me for that. I was sixteen—nearly, anyway—and I was pretty sure I was growing a beard. When I felt my upper lip, there was something there, not bristles exactly, not yet, but something. Feed the goats! Not exactly a manly task. And I had more important things to do.

In a couple of quick moves, I was around the corner and over the fence. I trotted up the hill as fast as I could without getting completely winded. Maybe I could convince myself I hadn’t really heard her. Maybe I could make her think I had already left. Not very likely, mind you—not with a mother who could make hardened murderers weep and confess with a single glance—but I could try, couldn’t I? And as I ran across the High Field, very close to the sky and far, far away from goats and scraps and mothers with Shamer’s eyes, I felt so light and free inside I could almost fly.

“There ye are, lad. We’d about given up on ye.”

Callan and Kinni and Black-Arse were waiting for me outside Callan’s tiny croft. It’s a strange thing, that croft. Callan is as tall as a house and as wide as an oak tree. When you see him outside, it seems as if he can’t possibly fit inside. But he can. He and his old gran both.

“Ah, likely his ma wouldn’t let her little boy come,” said Kinni.

I got fed up with Kinni sometimes. Most times, in fact. He was always going on at me about my mother, but I’d noticed that he lowered his eyes and called her “Medama Tonerre” just like everyone else—when she was around, at least. Kinni’s father was a merchant, and he paid Callan to teach him how to use a sword.

I liked Black-Arse better. Of course, that was not his real name. Really he was Allin, but no one ever called him that anymore. He loved anything that could go bang. One time he had got hold of some niter and a jar of petroleum, and boom! Suddenly Debbi Herbs had lost an outhouse. When she saw Allin running for dear life with a huge black spot on his singed trousers, she screamed at him: “Come back here, ye black-arsed bastard, and I’ll give ye what for!” And ever since, everybody has been calling him Black-Arse.

Black-Arse was the closest thing I had to a best friend here. If I had been born up here, we definitely would have been friends. But to Black-Arse and everyone else, I was still “the Shamer’s boy from the Lowlands,” and although everyone had been really helpful and nice and polite, they always somehow let you know that you were a stranger. A Highlander didn’t completely trust anybody he hadn’t known since he was in swaddling bands. The longer we stayed here, the more obvious it became to me that in their eyes, we simply were not clan, and never would be. And even though Black-Arse liked me much better, it was Kinni he would turn to if he was in trouble. Because Kinni was his great-great-cousin, and I was just a Lowlander. If I lived here for fifteen years, I would still be just a Lowlander. Sometimes it made me so mad I wanted to say the hell with it, the hell with them, and go back to Birches where I might still be the Shamer’s boy, but at least they had all known me almost since I was born. Sometimes I got so homesick for Birches that I would be about ready to cry. And that was just too bad, because we couldn’t go back. Cherry Tree Cottage, where we used to live, was a burned-out ruin, and Drakan’s men were still looking for my mother and my sister. And for Nico, who caused it all, in a way.

Every time we practiced, Callan found a new place for us. He was always saying that a good caravan guard must be able to fight anytime and anywhere—in the mud, on a mountainside, in a forest, or in a bog. Robbers lie in ambush where they choose. They don’t wait politely until you’ve reached firm, even ground.

On this particular day he brought us to a narrow dried-out gorge that had once been a riverbed. The bottom of it was full of round rocks and boulders, and the footing was terrible. If you forgot to watch your feet, down you went, and falling was a painful business on those rocks. But if you forgot to watch your opponent, it hurt even worse. Callan hit you hard for that. Most practice days, I took away quite a collection of bruises. Kinni sometimes complained, but Callan took no notice.

“Which would ye rather—bruises now or sword cuts later? If ye’ll not learn that block, ye’ll likely lose an arm the first time ye’re in a real fight.”

I listened, and kept my mouth shut. Bad enough to be a Lowlander—I had no intention of being a crybaby on top of it.

We trained until twilight. Some of the time we used heavy sticks, but in the end Callan let us use the swords, and the gorge echoed with a wonderful ringing sound every time the blades met. It sounded almost like bells, I thought. I sweated and stumbled and recovered, and not once did I think of my mother and her eyes, or of the stupid goats and their scraps. I just felt happy and warm all over, especially when Callan slapped my shoulder and said, “Well done, lad. Ye have the knack.”

The best thing about it was that I knew he was right. Even though I hadn’t been training long, I was already better than Kinni and Black-Arse. It was as if my arms and legs knew things that I didn’t: Hold the sword so to block that blow. Swing it just so or you’ll lose your balance. I loved my body at times like that, my clever body with its balance and strength and quickness.

Suddenly, a voice cut through the twilight: “Davin! Your mother is looking for you!”

For a moment, my body was not clever at all, but just an awkward collection of limbs. Kinni took advantage and slugged me on the shoulder, and I lost all feeling in my right arm. My sword fell to the rocks with a dull clank.

“Ye’re dead,” said Kinni triumphantly and prodded my chest with his sword. And all the joy and warmth and excitement certainly died.

“Running her errands again, Nico?” I rubbed my right arm sourly. “Haven’t you got better things to do?”

Nico stood at the edge of the gorge, staring down at me. His blue eyes were exceedingly cold, and he looked very much the noble, despite his commoner’s clothes.

“No, Davin, I haven’t, actually. You forget who your mother is. If not for her strength and courage, they would have flung my body on some middens long ago to feed the crows. I would have lost my head for three murders done by someone else. I owe her everything. And you owe her at least the courtesy to tell her how you spend your time. She worries about you.”

Kinni giggled. “Davin-baby,” he whispered, quietly, so Nico wouldn’t hear him, “Mama Shamer is so worried about her little boy.”

Angrily, I picked up my sword. I felt like clouting Kinni over the head with it. But I felt even more like flinging it at Nico and his stupid superior face. Who did he think he was, to preach about what I owed my mother? So I wanted to learn how to use a sword. What was wrong with that? What was wrong with learning how to fight, so that one day I’d be able to protect my mother against Drakan and all the other enemies Nico had made for her?

“Get along with ye, Davin,” said Callan. “We’re about done for the day. See ye in the morning, if ye still have a mind to join the hunt.”

I nodded. I had been looking forward to that hunting trip. Callan had lent me one of his bows, and I was getting quite good at hitting what I aimed at. But what if Nico told Mama about it, and she said I couldn’t go?

I climbed the edge of the gorge and started walking rapidly, hoping that Nico would leave me alone. No such luck. He waited until we were clear of the forest and could see the Dance, the great circle of standing stones on the hill just above our new cottage. Then he spoke his mind.

“Why don’t you tell her, Davin? You just disappear, and she has no idea where you go.”

“If she really wants to know, all she has to do is look at me. Then I’ll have to tell her, won’t I? Whether I want to or not.”

Nico seized me by the arm and forced me to stop. The twilight mist had made the air clammy and beads of moisture glistened in his dark beard.

“Why are you being so stupid? Don’t you see that that is the last thing she wants to do?”

What did he mean? I didn’t get it. But I was determined not to let my puzzlement show.

“Don’t call me stupid,” I snarled. “At least I do something. You just sit around, waiting for them to come and get you!”

Nico clenched his fists, and his eyes flashed beneath his dark brows. I almost wished he would go ahead and slug me so that we would have an excuse to fight. But he didn’t. Of course he didn’t—Nico prefers cutting people up with words.

“If you would get your nose out of your own backside for a moment, you might discover that she is trying to let you grow up. Has she asked why you have to wash that same poor shirt every week when you ought to have two other perfectly good ones to wear? And incidentally, you’ve been had. That thing is little more than a bar of pig iron. You’ll never get a proper blade from that.”

“If you’re so smart, why don’t you help me? You could train me much better than Callan can.” Nico was the son of a castellan and had had the best fencing masters his father’s purse could hire.

It took a while before he answered.

“If I promise to help you,” he finally said, “will you then tell your mother the whole thing?”

“It’s no business of hers. Does she have to know everything?”

“Why not? Are you ashamed of what you are doing?”

“No!” But I knew Mama wouldn’t like it. “Can’t I keep one little thing to myself? Nico, you could help me. You know you could.”

He shook his head. “I don’t care for swords,” he said. “And your mother wouldn’t like it.”

“You and your fancy likes and dislikes! If it hadn’t been for you, we wouldn’t have lost Cherry Tree Cottage. If only you had had the guts to strike when you had the chance, then—then—” I couldn’t finish. Nico was staring at me, and his face was deathly pale. He knew I was right. Last autumn he had had the chance to kill Drakan. Drakan who had murdered his father, his brother’s widow, and his tiny nephew. But he had used the flat side of the blade instead of the edge. And a few days later, Drakan and his men had burned down our cottage and killed almost all our animals.

Nico spun on his heel and stalked off without a word. I knew I had wounded him as surely as if I had stuck a knife in him. It would have been easier for him if I had just lost my temper and slugged him. And easier for me too, I think. I felt bad about that white face, knowing it was my fault. But I simply did not understand him. I couldn’t for the life of me understand why he hadn’t chopped the bastard’s head off. If it had been me, if Drakan ever again caused any kind of harm to Mama or the girls… that was why I spent so much time practicing. Because I wanted to defend them. Because I wanted to kill Drakan.

Mama and the girls were already having dinner when I walked in. Dina threw me a furious look across the kitchen table. After what happened last year, she had become a bit of a mother hen where Mama was concerned. But then, Dina had been there, in Dunark, in the middle of the whole bloody business. A dragon had tried to bite her arm off. That was another reason I wanted to learn how to use a sword. The next time some monster wanted to take a bite out of my sister, it would be me doing the dragon slaying, not Nico.

I took my bowl down from the shelf and pretended not to notice Dina’s furious looks. She has Shamer’s eyes just like Mama, even though she is still only eleven, and when she is angry, looking at her is a really bad idea. That glare—it’s a bit like being kicked by a dray horse. Rose, Dina’s friend from Dunark, who lives with us now, ladled soup into my bowl with the big ladle she has carved for us herself. She knows how to use a knife. Actually, she stabbed Drakan in the leg last year. The only ones who hadn’t fought Drakan in some way happened to be five-year-old Melli… and me.

“Why is Davin so late?” asked Melli, in her most innocent-sounding voice. “Where have you been, Davin?”

“Out,” I said sourly.

Mama didn’t say anything. Dina didn’t say anything. The silence was loud enough to crack an eardrum. I blew on my soup to cool it, and carefully did not look at either of them.

DINA

Pheasants on the Slope

When we got up the next morning, Davin had vanished. Again. Before breakfast, even. I didn’t eat much either. I was so furious with my brother that I could barely swallow my food. How could he behave like that, and at such a time too, with Mama worried sick over that business with the child peddler. Didn’t she have enough to think about?

“Eat your porridge, Dina,” said Mama absentmindedly, setting aside a bowl for Davin and covering it with a clean dishcloth.

“I’m not hungry,” I muttered.

“Oh? Is there anything wrong with the porridge?”

I shook my head. “It’s not the porridge, I’m just not—”

“Well, stop moping and eat it, then! Or feed it to the chickens, I really don’t care!”

Rose looked up in surprise. Mama rarely raised her voice over little things like that, but here she was, yelling at me, as if the whole thing were my fault. The unfairness of it brought tears to my eyes. I pushed back my chair with a jerk and went outside and did exactly what she had told me to do. The chickens cackled around my feet, jostling to get their share of this unexpected tidbit. The early morning sun played along their backs, raising golden gleams. The chickens we had now were all much bigger than the ones we had kept at Cherry Tree Cottage, and they were a beautiful roan color, almost like copper. Apparently, that was what Highland hens looked like—at any rate, all the other chickens in the vicinity looked exactly the same.

I heard the door open. That would be Rose, I thought, coming to share my troubles. But it was Mama. Without saying anything, she put her arms around me from behind and rested her cheek on my hair, and for a while we just stood like that, watching the chickens pecking and scrabbling and fighting over the remnants of the porridge.

“Hmm… well, at least they like my cooking,” said Mama, but this time it was a joke. This time she said it to make me smile.

“Davin is stupid,” I said viciously. “Why has he become so—so—” I couldn’t even think of a word to describe him.

“He is not stupid,” said Mama, sighing, and I felt her breath against my neck. “He is just trying to figure out how to be a man. I think it’s best if we can leave him alone for a while. I think we need to give him… a little growing space perhaps.”

I didn’t feel like giving him anything at all right now—unless it was a well-placed kick.

“He hardly ever looks at me,” I said, and suddenly I was crying, without wanting to and without being able to stop myself. When there are only four people in the whole world who are willing to look you in the eye, losing one of them really hurts.

“Oh, sweetie,” Mama whispered and tightened her arms around me. “Sweetie, I’m so sorry. I hadn’t even noticed. I suppose I’ve been too busy trying not to mind that he’ll no longer look at me.”

“Why does he do it?” I snuffled. “Why does he turn away from us like that?”

Mama didn’t answer right away. “I’m not entirely sure what’s going on with him,” she finally said. “But Davin… once he was just a boy, and he knew how to do that. Now he has to become a man, and I’m not quite sure he knows what that is supposed to mean. And it’s hardly something you and I can teach him. He’ll learn, though. And when he does, he’ll come back to us.”

“Are you sure?” My voice shook, and I knew I sounded like a little kid, hardly older than Melli. Because what if he didn’t? I knew very few grown men who would look a Shamer in the eye. Nico tried, but it hurt him; he felt guilty about so many things. The only one who did it unflinchingly was Drakan, and that was because he had no more shame than an animal.

“Of course he will,” said Mama. “If our Davin does not become the kind of man who can look us in the eye, then we’ve done a poor job of raising him, haven’t we?”

Again, she meant for me to smile. But I couldn’t do it.

At that moment, there was a warning wroof! from Beastie, our big gray wolfhound. Mama let go of me.

“Go and wipe your face, sweetie,” she said. “We have company.”

The visitor was a Laclan man, a slim, dark-haired gentleman with very fancy manners. He was dressed fancily, too. His shirt was elaborately embroidered, and instead of a common leather belt he wore a slim silver chain around his waist. A wool cloak bordered with the red and yellow Laclan colors was slung dashingly over one shoulder. He looked quite out of place in our lowly farmyard, among the squawking chickens.

“Have you found the child peddler?” The question burst out of me as soon as I saw the Laclan colors.