Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

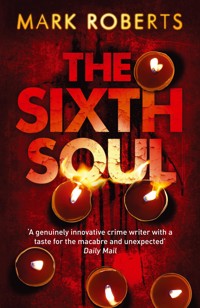

Six women. Six abductions. Six souls in peril... London is in the grip of a barbaric serial killer, dubbed Herod by the tabloid press. Four pregnant women have been abducted in quick succession, their bodies mutilated and dumped. When a fifth pregnant woman, Julia Caton, is taken from her home in the dead of night, DCI David Rosen knows that time is running out to save her... Then Rosen gets a mysterious phone call from Father Sebastian Flint, an enigmatic priest who seems to know rather too much about the abductions. When it emerges that Father Flint was once the Vatican's leading expert on the occult, the investigation takes an increasingly disturbing turn. But it isn't until Rosen discovers the existence of an ancient text - said to be the devil's answer to the bible - that the true horror of Herod's plan begins to unfold. Rosen is drawn inexorably to the killer's lair, where he will discover a terrible truth - that Herod's retribution is absolute, and that there are far worse things than death...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 384

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE SIXTH SOUL

Mark Roberts was born and raised in Liverpool and educated at St. Francis Xavier’s College. He was a mainstream teacher for twenty years and for the last ten years has worked as a special school teacher. He received a Manchester Evening News Theatre Award for best new play of the year. The Sixth Soul is his first novel for adults.

First published in hardback, trade paperback and E-book in Great Britain in 2013 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Mark Roberts 2013

The moral right of Mark Roberts to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 0 85789 786 2 Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 0 85789 787 9 E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 788 6

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For my wife, Linda

How beautiful you are, my darling!

Oh, how beautiful!

Your eyes are doves.

Song of Songs 1:15

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

PROLOGUE

In her dream, Julia Caton held her newborn child in her arms and was filled with the deepest love she had ever known. Slowly, the dream dissolved. At half past three in the morning she woke up and carefully positioned herself on the edge of the bed. She folded her hands across her swollen middle and whispered, ‘Baby.’ She stroked her bump. ‘I need the bathroom.’

There was no need to switch on the bathroom light because of the amber glow from next door’s brash security light, triggered by a yowling tom-cat.

She thought, This is a good rehearsal for all that getting up in the night. A smile spread across her face at the prospect of holding and feeding and loving her baby.

Next door’s security light clicked off automatically.

The bathroom was sunk into a darkness all of its own.

The door swung back silently behind her aching spine.

Julia made out the outline of her head in the mirrored cabinet above the bathroom sink. Outside, the tom-cat made a sound like a baby crying and the security light flared into life again. In the mirror, a shadow shifted. Her hands stilled at her side, her eyes two points of light in the glass. And beyond them, another pair of eyes glinted in the mirror.

She felt a sharp pain in the back of her left forearm, something suddenly piercing her skin. She opened her mouth and drew breath.

His hand flew to her face, his fingers digging into the privacy of her mouth, pressing down hard on her tongue and forcing down her lower jaw, stealing the scream from within. A hint of teeth flashed and the whites of his eyes shimmered in the dark surface of the glass.

As she slumped into his arms, a chain of cold thoughts flashed through her mind about the stranger in her bathroom.

She was the fifth pregnant woman he’d attacked. He was going to take her away. And she would never return.

And as the door closed on her senses, a voice whispered into the void.

‘I did not come out of darkness. I am darkness itself.’

1

On the way to Brantwood Road, just after he’d burned through the third of four red lights, Detective Chief Inspector David Rosen had been pulled over by a pair of constables in a BMW Traffic Car. With the engine still running, he’d shown his warrant card to them as his window slid down. Their conversation had been to the point.

‘Herod, fifth victim, Golden Hour.’

They waved him on.

Minutes later, at the cordoned-off scene of crime, Rosen braked hard. In spite of the need to move fast, he was frozen for a moment by a memory of the funeral he’d attended yesterday. He could still hear the raw grief of Sylvia Green’s mother as her daughter’s coffin disappeared behind a curtain in the crematorium. It was the fourth funeral he’d been to in as many months. And with each murder, the interval between killings was growing shorter.

Four victims, their faces and names, their lives, all constantly jostled inside his head.

Four dead women, and the killer was as far away as he had been from the first. He tried to breathe slowly to release the solid band of stress around his chest.

‘Go!’ he said to himself.

He hurried from his car to the back of the white Crime Scene Investigation van, where Detective Sergeant Carol Bellwood was standing, already suited and ready to enter 22 Brantwood Road. He snatched a white protective suit from the metal shelf of the van.

Light beads of rain had settled on Bellwood’s black hair, arranged in plaited rows tight against her scalp.

‘How long have you been here?’ asked Rosen, dressing.

‘Three minutes,’ replied Bellwood.

Rosen took a mental snapshot of the scene.

It was just past seven o’clock on a dark March morning. Two rows of large 1930s semis faced each other across an affluent suburban road. The pavements on either side were lined with trees, and each house had three metres of garden between the front door and the fence that bordered the pavement.

To the east, the crescent moon over Brantwood Road wasn’t the only source of light. Number 22, the house they’d been called to, was floodlit by the NiteOwl searchlight on the roof of the Scientific Support van.

Rosen glanced at the house next door.

‘Number 24,’ he said. ‘It’s the only house I can see with the lights out.’

Its windows were black. All the other houses, from the teens through to the thirties, were lit up, the neighbours awake and aware of a rapidly growing police presence.

Rosen, dark-haired, thick-set and middle-aged, was in a hurry to get his latex gloves on, but the more he hurried, the more he failed.

‘Here,’ said Bellwood, gently. ‘Time is of the essence.’ She unrolled the bunched tangle on the back of his hand and Rosen felt a tingle of embarrassment at a young woman’s touch. ‘Curtains are flapping.’

‘I hope someone’s seen something,’ said Rosen. ‘Let’s find out what the uniforms have come up with.’

Rosen stepped into his overshoes without any of the fuss the gloves had caused him.

Three uniformed officers, a sergeant and two constables, stood at the gate of number 22, guarding the blue and white cordon, grim-faced, silent.

‘Chief Inspector Rosen,’ said the sergeant.

‘Sergeant,’ replied Rosen, knowing his face from somewhere but not his name. ‘Who was here first?’

‘The constables responded,’ the sergeant informed him. ‘I took over the scene on arrival.’

‘Who’s in the house?’ enquired Rosen.

‘Scientific Support.’ The sergeant gave his book the merest of glances, checking the names on his running log of those he’d allowed through. ‘DC Eleanor Willis and DS Craig Parker.’

‘Where’s the husband?’

The sergeant nodded towards a nearby police car, its back door wide open, where a big man in neat blue overalls, feet planted on the pavement, head down, vomited into the gutter.

As Rosen watched the husband, he noticed a newly promoted detective constable, Robert Harrison, leaning against the passenger door of an unmarked car, staring in his direction. Caught in the act, Harrison turned his head away.

‘What did the husband tell you?’ Rosen directed his attention at the constables.

‘That he was called out at twelve minutes to three this morning,’ the first constable replied.

‘Twelve minutes to three? That precise?’

The second constable pointed at a green van parked near by, a skilled tradesman’s Merc. ‘If you look at the van, sir.’

‘I clocked it on the way in,’ said Carol Bellwood. ‘It says on the side of the van, “Phillip Caton 24/7 Bespoke Plumbing Central Heating Engineer”. There’s a mobile number and a picture of Neptune wielding his trident and barking the waves down into submission. Mr Confident or what?’

‘Or what.’ Rosen observed Caton wiping his mouth on his sleeve.

‘He gave us a time,’ said the first constable. ‘And then he fell apart.’

‘We had to frogmarch him out of the house before he threw up all over the crime scene.’

‘Any sign of a forced entry into the house?’

Their silence was enough. Caton raised his eyes from the puke in the gutter to the gaggle at his gate.

‘Robert!’ Rosen broke the moment and beckoned him over. Harrison came to the fence.

‘David?’ said Harrison.

‘Carol’s going to talk to the husband.’ Rosen pointed to Phillip Caton. ‘Listen to her questioning him, make notes, no butting in.’

Rosen turned to the sergeant.

‘I’m taking over the crime scene now. Thank you for what you’ve done. Please stay on the door and allow only DS Carol Bellwood here over the threshold until otherwise instructed.’

——

JUST AS HE stepped into the house, he could hear behind him a man crying out in renewed distress. Rosen was glad it was Carol Bellwood, not he, who had the task of extracting information from Phillip Caton. After so many years as an investigative officer, he could not help but wonder if he was witnessing a man in profound torment, or the performance of a magnificent actor.

2

Scientific Support had worked hard and fast.

From the front door to the stairs, and up each step to the bathroom and bedrooms above, DS Parker and DC Willis had laid down a series of aluminium stepping plates. Rosen picked a path across the makeshift walkway, into the heart of the hall, any evidence left on the carpet being protected by the raised metal plates.

Rosen paused at a picture. On the wall was a framed photograph, a wedding portrait of Phillip and Julia Caton: she veiled and pretty in white, he awkward in top hat and tails. But their smiles were broad that day and the sun had shone on them, just as it had done on him and his wife, Sarah, many years earlier.

Rosen headed up the stairs with a renewed sense of sorrow.

On the landing at the top of the stairs, DC Eleanor Willis, pale and red-haired, used a pair of long-handled tweezers to drop a hypodermic needle into a transparent evidence bag and then peered into it.

‘There’s blood on the needle,’ she said to Rosen as he passed.

‘But it won’t be his,’ he replied.

DS Craig Parker was on his knees, cutting the thick, green carpet with a Stanley knife where it met the skirting board at the bathroom door. The carpet showed a fresh drag mark from the bathroom towards the top of the stairs. Parker pointed this out to Rosen.

‘He got her in the bathroom,’ he said. ‘Dragged her to the stairs.’

‘I love the sound,’ replied Rosen, ‘of a Geordie accent on a cold, gloomy morning.’

‘And a very good morning to you, you cheerless Cockney git.’ Parker peered at Rosen above his mask and added, ‘Are you OK, David?’

Rosen stooped. ‘Come here often, Craig?’

By way of answer, Parker smiled sadly. ‘We can’t find a point of forced entry.’

Craig Parker’s face was the human equivalent of a bloodhound’s. His weary eyes had seen enough and the bags underneath betrayed a tiredness that was three months short of retirement after thirty years in the Met.

‘Eleanor!’ Parker got to his feet slowly as his assistant appeared from the bedroom and handed the bagged hypodermic to Rosen.

There was a little fluid left in the chamber. ‘Pentothal, no doubt. Herod’s anaesthetic of choice. The hypo must’ve fallen out as he got her out of the house,’ said Rosen.

Willis stood opposite Parker. On the count of three they raised the piece of carpet in a single clean lift and carried it into the nearest bedroom, an empty space at the back of the house.

‘Anything in the bedrooms?’ asked Rosen.

‘Nothing so far.’ Nothing was certain; so far was full of hidden promise.

‘Craig, how long to go through the whole scene: house, gardens, street outside?’

‘Three days.’ Parker’s voice echoed in the back room.

‘If the pattern stays the same,’ said Rosen, ‘she’ll be dead by then. No sign of forced entry, you say?’

‘First thing we looked for. Nothing.’

‘Next door, number 24?’

‘No one lives there,’ Willis observed, heading to the bathroom, ‘judging by the back garden, the state of the windows and the paintwork outside.’

By contrast, the interior window frames of the bathroom of number 22 were sharp, their brilliant whiteness highlighted as Willis dusted them with dark fingerprint powder.

Rosen looked around at the closed bedroom doors. ‘Which one’s the baby’s room?’

Willis pointed with the bristles of her fingerprint brush.

Being in a nursery made for a baby who would probably never sleep in there, or play, or cry, or breathe between its cloud-daubed walls, filled Rosen with utter sorrow. His failure to do anything so far to stop what was happening was almost unbearable.

Rosen caught the ghostly outline of his reflection in the glass of the window, the boy-like tangle of black curly hair contradicting the jumbled network of wrinkles and shadows on his pale face.

He looked out on the neat suburban road, at the desirable cars and the enviable houses, and focussed on DC Robert Harrison standing behind Carol Bellwood as she tried to talk to Phillip Caton. His gaze wandered.

The trees in the street were tall and broad and narrowly spaced apart.

It was a discreet road, a secluded avenue, a nice place to live.

Rosen called Craig Parker, who joined him at the bedroom window.

‘Can you see across the street through the trees? Can you?’ asked Rosen.

‘No, I can’t see much, David,’ replied Parker.

‘And that’s exactly what he banked on. I’m going into number 24.’ I want to get out of here.

‘Why?’ asked Parker.

‘No forced sign of entry. No pregnant woman in London’s going to open her front door in the dead of night, not given the current climate, not given what’s happened. I’m going next door. I’m looking for a point of entry.’

‘David, man, how could he get into number 22 through number 24—’

Rosen held up a hand. ‘I need to check.’

When Rosen reached the street he noticed that, while he’d been inside number 22, Caton had turned a curious shade of yellow, the colour of wax. A terrible idea crossed Rosen’s mind. He hoped Caton’s anguish would not be compounded by having made an easy mistake as he left the house to go to the job.

On your way out, Rosen wondered, in the dead of night, did you accidentally leave the front door open?

3

Each panel in the fence between numbers 22 and 24 Brantwood Road was old but perfectly intact. The decision to widen out the crime scene came from a combination of experience and instinct. Back in ’99, Rosen had been at a scene of a crime where there was no evidence of forced entry, but it had become evident that the killer had entered through a vent between adjoining flats.

He looked up at the roof of number 24: a patchwork of slipped and missing slates, making the house and loft space vulnerable to the elements.

He glanced at his watch. Eight o’clock. Time was flying. A whole hour had passed in what felt like a minute.

To the front of the property, a locked garage attached to the side of number 24 blocked his way to the back garden. Taking hold of the top of the fence separating numbers 22 and 24, he steadied his foot on the thick knot of a shrub and hauled himself over. The fence panels creaked under his weight as he jumped down into the garden next door.

He watched his feet. The ground was littered with the faeces of several types of beast. At eye level and within an arm’s length, a bird flew out of a bush.

‘All right in there, David?’ Bellwood’s voice came from the garden of number 22.

He called back, ‘Yes!’ but wasn’t sure that this was the truth.

Rosen turned to the sound of Bellwood climbing over the fence. She jumped down gracefully into the garden of number 24.

A bin, long overturned by some fox or other scavenger, lay on its side near the house. The rubbish – food packaging and newspapers showing headlines and sporting triumphs and disasters from eighteen months ago – lay matted on the earth leading to the back door.

Rosen felt his pulse quicken as he got closer to the door. He looked at his watch again: it was a few seconds past eight. He thought of his wife, Sarah, and her appointment with their GP. Time was marching on. He wanted to go with her, he’d promised he would and then this . . . Herod’s fifth miserable excursion into other people’s lives.

Something lurched inside him. Every nerve was made jagged by what he saw.

The back door of number 24 was slightly open, a glass panel in the door absent from its frame, cleanly removed.

Someone had gone to the trouble of not bashing the door down, not attracting the attention of the neighbours. Rosen eyed the area around the missing panel. It was a cautious job well done.

‘Carol?’

‘Yes?’

‘Can we rule the husband out at the moment?’

‘His story held up. I called his client. He was in Knightsbridge, as he said.’

‘There’s been a break-in. Who’s here from the team now?’

‘Harrison’s on float, DS Gold is with Caton, Corrigan and Feldman are here and knocking on the neighbours’ doors. David?’

‘Yes?’

‘Harrison’s a liability.’

‘What did he do?’

‘Just when you were going into number 22, Caton said, Do you think Herod’s got her? And Harrison chimes in, It looks like that, yeah. Caton went into hysterics. I don’t like him, David.’

‘I understand.’ It explained Caton’s sudden sobbing fit. ‘Did Caton say anything – anything useful?’

‘He kept asking if we knew what Herod was doing with the foetuses.’

‘And you told him what?’

‘We didn’t know for sure. I avoided the forensic psychologist’s word trophy. Do you buy that rather obvious speculation, David?’

‘No,’ said Rosen. Unable to offer an alternative theory about the absent babies, he went for something practical. ‘Go and call for a second Scientific Support team for number 24.’

Using the tip of the little finger of his left hand, he pushed the door open at its top right-hand corner.

It was an old lady’s house.

There was an aura, as if someone had died there long ago, undisturbed by compassion or duty, hidden in the muffled light.

——

IN JUST UNDER twenty minutes, a second Scientific Support team had arrived, pulled in from Shepherd’s Bush. Silently and efficiently, they had plated the main passageways from the back door of number 24 to the front door, the stairs and each of the main doorways, upstairs and down.

As the second officer came down the stairs, he said to Rosen, ‘There’s a cadaver in the bed, main bedroom, front of the house. It’s been there some time. We didn’t touch it.’ The team looked in a hurry to leave. ‘We really need to talk with DS Parker next door, sort out a game plan.’

The Scientific Support officers left. Rosen, alone now, felt oppressed. Something of the earth, something foetid, perhaps a fungus, was growing in the fabric of the house, feeding on the wood its spores burrowed into, irrigated by the damp that seemed like an indoor weather system unique to number 24.

Where were her relatives? A five-bedroom semi in Brantwood Road added up to a big inheritance. Where were the claimants to this legacy? Why had no one attempted to even clear the house, let alone sell it?

He imagined his wife Sarah, old and alone, dying, and her death going unnoticed, their home crumbling, broken into by some lunatic, then explored by policemen desperate for clues.

He tried the light switch but the power was dead. As he moved further into the house, it became dimmer still. The red-flocked wallpaper, turning green and brown from the damp, seemed to be dissolving into the deepening shadow.

Persian rugs shifted under Rosen’s feet, reminding him of the uneasy sensation of the bogus floors of a fairground funhouse. But he could see no physical sign of an intruder, just an old lady’s world frozen in time. Somewhere else, in another room, a well-made mechanical clock still ticked, a heartbeat to the house.

A patch of yellow light appeared on the wall, its source directly behind him. Rosen span round and Carol Bellwood stepped from the shadows.

He was pleased that the newest member of the team was backing him up.

‘How’s Caton holding up?’ asked Rosen.

‘Not good, but we’re done with him for now.’

As they ascended the stairs, years of stale air formed a backdrop to dust motes that shimmied in the torchlight.

Rosen stopped near the top. Every door upstairs was closed, except one.

He walked towards the open bathroom door.

Weary light filtered into the gloom through the frosted glass.

‘David? Are you OK, David?’

He was staring, lost in thought, looking directly up at the ceiling, at the wooden door to the loft space.

‘Let’s check the bedrooms,’ he said.

——

IN THE MAIN bedroom, the top of a human head was visible on the pillow. The quilt on the bed was raised, giving the impression of a relief map, with the outline below that of a human body. Rosen tugged the edge of the quilt but it was stuck to the sheet on the mattress. When he pulled a little harder there was a tearing sound, cloth from cloth, surface from surface. Bellwood entered behind him, her torchlight illuminating what was left of the body.

I’m sorry, thought Rosen. I’m sorry you’ve been left here without anyone to mourn you or mark your passing.

She lay foetal in death, a frail skeleton, knees tucked to elbows, carpals to teeth, her skull nestled on a clump of grey hair.

Rosen lowered the quilt.

Whatever had caused her death, she’d been left to rot into the bedding and dry out. The thought angered and saddened Rosen in equal proportions.

Tweed. There was a half-used bottle of Tweed perfume on the old lady’s dressing table and an ivory hairbrush in which a gathering of grey hairs remained for ever trapped in the network of bristles. Her jewellery box was open, neatly arranged, undisturbed. On the dressing table next to it was a gold, heart-shaped locket. It was open. On one side of the heart, a picture of two children, a teenage girl and a small boy; on the other side, a small lock of dark hair.

‘Who are you?’ Rosen asked the children in the locket.

‘And where are you now?’ Bellwood stroked the locket with her light.

‘What about the other bedrooms?’ asked Rosen.

‘All empty save the one next to this. Shall we?’

The room next door to the old lady’s room was a museum piece. A teenage girl’s room, early to mid-1970s, Jackie magazine open on the single bed, an early stereo system with an RAK 45 record of Mud’s ‘Tiger Feet’, and posters on the wall of David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust and Paul Gadd as Gary Glitter.

‘I wonder?’ said Rosen, eyeing a framed photograph of a skinny thirteen-year-old girl. He picked up the frame, speculating as to what had become of her.

‘Maybe the old lady was hanging on to a moment in time, the girl grew up and—’

‘Maybe.’ He looked at the photo – the girl’s clothes, her blonde hair in a feather-cut, and figured it was around 1973. ‘She was a few years older than I was back in 1973. Not that our paths would have crossed in a million years,’ said Rosen, wistfully.

‘How come?’ asked Bellwood.

‘ I grew up in Walthamstow. This kind of street, this neighbourhood, was beyond my dreams.’

Rosen was quiet for a long time as he stared at the girl’s picture. He sighed; the dusty air was thick with memory of a time before Carol Bellwood was born.

‘I had a daughter . . .’ Rosen stopped articulating the thought that had escaped unchecked from his mouth and averted his eyes from the bewilderment in Bellwood’s face. He turned his mind away from the thought of Hannah, the baby who’d once slept in his arms, and raised his voice a little. ‘Come on, let’s crack on. I think I’ve seen a precedent for this.’

Rosen walked back to the bathroom, Bellwood following.

‘Back in 1999, in Battersea, a thwarted boyfriend used the flat next door to get to the woman he both loved and hated. It was an ugly murder.’

Rosen looked around the bathroom, pausing on the ceiling for a beat, considering a possibility. He almost smiled as his eyes returned to Bellwood’s face.

‘Carol, I think I know how Herod got into number 22.’

4

Ten minutes later, back in the bathroom of number 22, Eleanor Willis arranged a set of folding steps beneath the loft door.

‘David, if you’re right about the loft space,’ said Parker, ‘you could have enough material up there to tell us what size shoes his granny wears.’

‘Am I going to get that lucky?’ asked Rosen. ‘I haven’t had much luck so far.’

As soon as he said it, Rosen thought of Phillip and Julia Caton, and the four other broken couples, and he deeply regretted the note of self-pity.

‘However, it depends upon the state of the loft space. It could be almost impossible to retrieve, for instance, a single relevant human hair from all that fibreglass insulation, decaying newspaper, life debris, and whatever crap’s been up there since the thirties when these semis were built.’

Wearing latex gloves, Parker mounted the steps to the loft space, lifted the unhinged door and carefully removed it from the hatch, an enigmatic smile forming on his lips.

‘What is it, Craig?’ asked Rosen.

‘He sure had a good view of life in the Caton’s bathroom,’ said Parker, eyeing the loft door as he lowered it down to Eleanor Willis. As she took it by the edges Rosen resisted the urge to say, ‘Be careful.’

‘Thumbnail-sized hole in the wood,’ said Willis. ‘Enough, I guess.’

Willis raised the door carefully in front of her face, closed one eye and peered through it directly at Rosen.

He mounted the steps into the chill air and considered: a hole in the board covering the loft entrance. Enough to see through? Right into the bathroom. A good view into the most intimate of moments.

He climbed another step and, raising his head above the loft entrance, shone a beam of torchlight into the darkness. A trivial combination of sensory details were indelibly stamped on his memory: the distant roar of a bus, caught in the acoustics of the loft, and the intense cold trapped in the rafters. Then the rain started.

There was an adjoining wall between numbers 22 and 24, supporting the weight of the roof of both houses. A skin of fresh dust lay across the newly panelled floor of the loft of number 22. In the middle of the shared wall, there was a small hulk of darkness where bricks were missing. He shone a light on the wall and took a close look at the gap. It was large enough for an average-sized man to squeeze through.

Rosen eased his way down the ladder. ‘The mortar in the adjoining wall’s addled by the look of it, probably due to the state of number 24’s roof. It can’t have been a big task to get the bricks out. He’s tunnelled his way through into here from next door. He broke into number 24, got into the loft and took the bricks out from that side.’

He turned off his torch.

‘This is his fifth time round, but it’s the first time he’s abducted from within the victim’s home. Either this isn’t Herod’s work at all or he’s got the dangerous daring urge now. This could be costly to him, very costly. Maybe all of a sudden he believes he can be as reckless in abducting his victims as he is in dropping off around London what’s left of them.’

Rosen picked up Willis’s sigh behind her protective mask, the subtle tightening of her body language. He noted too that Bellwood had noticed her colleague’s reaction to Julia Caton’s probable fate.

‘Carol,’ he explained, ‘DC Willis was the first officer to see Herod’s handiwork with her own eyes, with no warning, no prior knowledge of what to expect.’

Eleanor Willis propped the loft door against the bath and took a string of pictures of it with her digital camera, then turned to Bellwood.

‘I was first to arrive at the scene when Jenny Maguire’s body was discovered,’ said Willis. ‘The surgical removal of the baby was clumsy, the work of one nervous butcher. We found out from the autopsy that he’d used a surgical scalpel, but it looked as if he’d hacked away with a blunt tin opener. His technique improves each time, the line of incision straighter, cleaner.’

The steady rain now fell harder on the shared roof of numbers 22 and 24 Brantwood Road. The noise of the rain clattering on the tiles echoed in the loft space above them.

‘David, Carol, come and have a look at this,’ Craig Parker called from next door.

Rosen and Bellwood followed the sound of Parker’s voice to the door of the smallest of the five bedrooms, used as a boxroom. Parker made a theatrical gesture towards an assortment of junk and said, ‘Voilà, man!’

‘What am I looking at, Craig?’

Parker pointed directly at a set of aluminium ladders propped against the wall. ‘Herod gets down from the loft, then uses Caton’s ladders to straighten up the loft entrance, putting the ladders back in place here in the boxroom before he swoops off with the missus.’

‘What do you make of it, David?’ asked Bellwood.

Rosen glanced at his watch. It was twenty past nine.

‘His nerves have settled and he’s reached the stage where he’s absolutely buzzing from what he’s doing. What do you think?’ Rosen batted the question back to Bellwood, Parker and Willis.

‘If he’s changed course midstream,’ said Bellwood, ‘and he’s stopped taking women from public spaces to start making home visits, can you imagine how that’s going to play in people’s heads when it comes out?’

‘How many pregnant women are there in Greater London?’ asked Parker.

‘Ninety thousand or thereabouts,’ replied Willis.

‘Ninety thousand women like sitting ducks in their own homes.’

Rosen imagined the public terror this new development would cause and hoped, in the face of the evidence, that this was not the work of Herod. But when he considered everything that had happened in the Catons’ home and in the house next door, he could not see how it could be otherwise.

‘This hasn’t been some random choice. This home visit’s been a ninety thousand-to-one call. Herod knows this building better than the people who live in it.’

5

Rosen stood outside the kitchen door of 22 Brantwood Road at the side of the house. A trio of newly arrived uniformed officers, dressed in protective suits, approached him.

‘Sir, where do you want us to start? Front garden or back?’

‘Back garden, number 22. Then, move it over next door. I apologize in advance. It’s an absolute mess. But that was the run-up to his point of entry.’

The rain was steady and cold. Alone again, Rosen scrolled to SARAHMOBILE on his phone. It rang.

His wife had recently had sharp abdominal pains, leading her to take time off from her teaching post. She had only ever been off work once before for a protracted period of five months’ sickness. Anxiety gnawed at Rosen about what might or might not be causing her such pain. He wished that he believed in God so that he could pray it wasn’t anything life threatening. But he didn’t believe in God and neither did she.

‘Hi, David.’

She sounded bright.

‘Have you been in to see the doc?’

‘Yes.’

‘And?’

‘He thinks – he’s pretty certain it’s a peptic ulcer.’

‘Good!’

‘Good?’ Sarah laughed.

‘It’s not good in itself . . .’

They had briefly discussed the possibility of cancer on a few occasions and it had played constantly on Rosen’s mind ever since.

‘Yes, I know what you mean. It could’ve been a whole lot worse.’

‘Where are you?’ He changed tack.

‘I’m in the car park at work, summoning up the courage to face 10M, today’s lesson, “Where is God in the face of evil?” Where is God in the face of 10M?’

In the middle distance, Phillip Caton got into the back of an unmarked police car with DS Gold up front. It would be taking him to Isaac Street Police Station for a more formal interview.

‘A peptic ulcer,’ said Rosen. ‘So what’s next?’

‘He’s referred me to Guy’s. I’ve got to have a barium meal and a scan just to clarify if his diagnosis is correct. Oh, oh God . . .’

‘Sarah, what’s up?’

Her car door opened and he heard the sudden lurching of his wife being sick on the car park tarmac.

He waited for what felt like a long time.

‘I’ve just been sick,’ she confirmed.

‘Any blood in it?’ he asked.

‘No.’

‘Good.’

‘David, you’re starting to annoy me. Intensely.’

‘I’m sorry. Maybe you should go home.’

‘I might as well be in discomfort but surrounded by people and busy, than sick and at home alone. Besides, I don’t think I’ll be sick again.’

‘When’s your appointment?’

‘The GP has to contact the hospital, and the hospital send for me when they have a space in clinic. I’ll have to go whatever the time.’

The wind shifted direction and a blast of rain hit Rosen directly in the face.

‘How’s it going there?’ she asked.

‘Another abduction, another death, no doubt,’ answered Rosen.

‘Where is God in the face of evil? Answer: there is no God, just a whole lot of evil,’ concluded Sarah.

‘And you the head of RE in a Catholic school, Mrs Rosen.’

‘Don’t pipe it too loud, David. Remember, two salaries are better than one. What time will you be home?’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘Then I guess I’ll see you when I see you. Sometime late tonight perhaps?’

‘I’ll be late, yes, and I’m sorry I couldn’t be with you this morning.’

‘Don’t worry. Others have it worse than us. I love you, mate.’

‘I love you, too.’

‘Gotta go. Oh, 10M, what a life . . .’

He ended the call, watching the rain. She was bearing pain and discomfort with a spirit that reminded him of one of the many reasons why he loved her from the pit of his being. If it was him with a peptic ulcer, he’d have griped to Olympic standard.

Pocketing his phone, Rosen felt the sudden and subtle weight of a presence behind him.

He turned his head slowly to see DC Robert Harrison walking towards him from the back garden.

‘What are you up to?’

Harrison held up the digital camera in his hand.

‘Using my initiative, sir. Photographing the back garden in the absence of a direct order and with nothing else to do.’

‘How long have you been there?’

‘Where?’

‘Behind me, Robert, behind me?’ Listening in on my phone conversation.

‘I’ve just come out of the garden.’

The open gate to the garden swung back against the fence, slamming against the wooden frame and making the wind and rain seem suddenly sharper, even ill tempered.

‘OK, Robert. Go next door. You can be in charge of the fingertip search of number 24’s back garden.’

Silence.

‘Sure.’

Harrison walked away. ‘I love you, too,’ he muttered.

‘What was that?’ asked Rosen.

‘Just thinking out loud, sir.’

6

Julia Caton was woken by the kicking of her baby inside her womb.

For a few clouded moments, she thought she was dreaming. And in those seconds, as the baby moved, she felt his shifts, rolling and turning, the pressure of his hands and feet pressing the sides of the amniotic sac. It was these gathering sensations that made her realize that, even though she didn’t know where she was in that bizarre dream, she and her baby were alive.

Julia opened her eyes to pitch darkness. She ached all the way down her left side, from her shoulder to her ankle. She blinked a few times and strained to see but there was no relief from the dense blackness. She wondered if she’d gone blind.

She was floating on the surface of lukewarm liquid and her baby was moving with the growing impatience of a life waiting to be born. How could her bed be so liquid? Because it was a dream, that’s how, like a dream after too much wine.

As she grew more wakeful, she became aware, without checking, that she was naked.

She raised a hand close to her face, disturbing the surface of the liquid as she did so, but she couldn’t see her fingers even as they brushed the tips of her eyelashes.

The back of her hand came into contact with a smooth surface that felt curved and plastic. The word lid slipped into the front of her mind. Lids may lift.

She raised her other hand, palm up, and pushed with both against the cool plastic. The lid didn’t budge. Julia knew that they were locked in a container of some kind, floating, floating.

She closed her eyes and took a deep breath to fight down the rising panic, the unwanted gift of delayed shock. She listened to the air rushing into her nostrils, felt her ribcage rising with the intake, and this was all she could hear.

The baby – she had learned it was a boy on the second scan – stilled inside her. It was as if he was obeying some secret command telepathically delivered from mother to son.

‘Good boy,’ she whispered. ‘Don’t move.’ Her voice was ethereal in the liquid silence. Talking was a mistake. The physical action of speech set off a taste in her mouth and she felt the urge to be sick.

As the sound of her voice sank into the darkness, and smell and taste overtook her senses, memory erupted in nuclear flashes in her mind’s eye.

In the bathroom, she had felt a sudden sharpness in her forearm and a hand in her face. The sense that she was dreaming evaporated as the stone-cold wind of reality thrust her into wakefulness.

He didn’t come out of darkness, he was darkness itself. The thought assailed her, and the thread of then and now connected.

‘Jesus!’

She dipped her fingers into the solution on which she floated and sniffed them.

There was no perceptible scent. Slowly, she opened her lips and allowed her fingers to touch her tongue. Salt. Salt water. They were floating on a solution of salt water, locked in the dark with no sound coming in.

She recalled a name: Alison Todd, the second mother to go missing just over seven months ago, the discovery of her body filling the news headlines on the day Julia had learned that she was pregnant.

Of the four murdered mothers, Alison’s case had affected Julia most deeply, the thought of her mutilated body casting a long shadow over their celebratory supper.

Phillip had tried to dismiss Julia’s fears, but they had remained all through her pregnancy, sometimes singing loudly, sometimes muttering darkly, but always there.

There were sides to the thing that they were locked inside. Her fears took a collective breath and started screaming inside her head.

‘Oh my Jesus!’

Julia could feel the blood draining from her limbs, the lightness in her brain.

A stressed mother stresses an unborn baby!

A received wisdom from the antenatal clinic she’d attended came back to her like a radio signal from deep space, a message from a distant world that she and her baby were now no longer a part of.

A stressed mother . . . stresses . . . an unborn . . . baby.

She couldn’t get her breath.

She heard her heart beat against her ribs, picking up pace by the second, and felt it as a pulse behind her eyeballs.

Instinctively, she folded her arms across her middle, covering her baby with the armour of flesh and bone.

Phillip had tried to talk over television news broadcasts that had reported the discovery of Alison Todd’s body and the growing details that were released by the media. But Phillip wasn’t around all the time, as when he was asleep in the pit of night and she had wandered downstairs and come across the BBC twenty-four-hour news channel.

Footage from the scene of the discovery of a body: blue and white tape cordoning off an area around Lambeth Bridge; the grimness of the reporter’s face as she recounted from the place where a second body, believed to be that of Mrs Todd, was found by a man walking his dog at dawn.

The police were refusing to reveal whether the mother was dead or alive when the killer performed a forced Caesarean section to remove the baby, along with pieces of the womb. The precise cause of Alison Todd’s death was unknown; there had been a media blackout on the detail, to weed out crank confessions.

Rather her than me.

Her own words burned a hole in her memory.

She wept in the darkness, using all the strength in her diaphragm to still the scream, the cry from her heart and her throat. When her baby gave a sudden sharp kick, her willpower collapsed.

The lid was low and her scream bounced back into her face. She drew in another breath and cried out for her mother, plummeting into hysterical tears as the word died on the lid inches from her face.

7

Know Your Enemy . . . London’s Drug Dealers and Addicts.

The bank of faces on the wall of the open-plan office of Isaac Street Police Station gazed into the fluorescent silence. In contrast with the faceless Herod, they looked like a reasonable bunch of boys and girls. As with budgets, space was tight and the office doubled up as the incident room for the ongoing murder investigation.

It was nine o’clock at night and DCI David Rosen had been on duty for just over fifteen hours. Reaching the point of fatigue that should have sent him home for food and sleep, he remained in the office, held there by an uneasy instinct. He’d phoned his wife Sarah, apologized for his absence. It was nothing new to her, and she was up to her eyes in marking her pupils’ exercise books.

Spread across Rosen’s desk was a colour map of London, on which abduction points were marked with red crosses and numbers. The body drops-offs, the blue crosses, seemed to form no discernible pattern. Jenny Maguire, victim one, in the lake at St James’s Park. Alison Todd, victim two, under Lambeth Bridge. Jane Wise, victim three, at the corner of Victoria Street and Vauxhall Bridge Road. Sylvia Green, victim four, outside the Oval cricket ground. Where would Julia surface? Rosen pored over the map, hoping for inspiration.

He opened Outlook Express. There was one potentially meaningful email, with an attachment, from Carol Bellwood.

David, I loaded all the significant information from this morning’s scene of crime at 22 Brantwood Road and 24 Brantwoood Road into HOLMES. Two hours later and every data permutation possible, I’m sorry to say there have been no matches.

Sorry, Carol

PS check att, with regard to this morning’s talk, is this what has happened to the babies?

HOLMES contained all the recorded data for every reported crime, solved and unsolved, in the United Kingdom. If Bellwood, the best HOLMES reader Rosen knew, couldn’t squeeze something useful out of the database that cross-matched details from all crime recorded in the UK, then no one could. It was a blow and he swore sourly as he breathed out.

He clicked on the attachment, opened it and muttered, ‘Jeez!’ at the picture on his screen. It was a stock image of a foetus preserved in a specimen jar, the whiteness of its perfect skin patterned with an elaborate network of veins. The world around him fell away. There was something unbearable about the picture.