18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

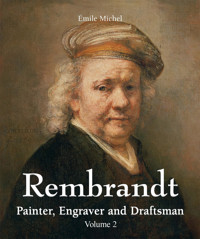

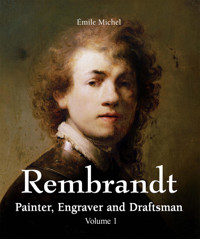

As famous during his lifetime as after his death, Rembrandt (1606-1669) was one of the greatest masters of the Dutch Golden Age of the 17th century. His portraits not only transport us back to that fascinating time, but also represent, above all, a human adventure; beneath every dab of paint the spirit of the model seems to stir. Yet these portraits are only the tip of the Rembrandt iceberg, which consists of over 300 canvasses, 350 engravings, and 2,000 drawings. Throughout his oeuvre, the influence of Flemish Realism is as powerful as that of Caravaggio. He applied this skilful fusion of styles to all his works, conferring biblical subjects and everyday themes alike with an unparalleled and intimate emotional power. Émile Michel remains a reference in Flemish painting. A result of years of research, Rembrandt: Painter, Engraver and Draftsman is one of his major works.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 438

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Émile Michel

Author:

adapted from Émile Michel

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

© Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-64461-782-3

Contents

The Beginning of His Career

A Dutch Painter

Success

Rembrandt’s Reputation and Saskia’s Death

Rembrandt’s Technique and His Genius

A Strenuous Twilight

Conclusion

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

The Beginning of His Career

His Education

Rembrandt was born on 15 July 1606 in Leyden. The date 1606, although very probably the year of his birth, is not absolutely above suspicion. Rembrandt was fifth among the six children of the miller Harmen Gerritsz, born in 1568 or 1569, and married on 8 October 1589, to Neeltge Willemsdochter, the daughter of a Leyden baker, who had migrated from Zuitbroeck. Both were members of the lower middle class, and in comfortable circumstances. Harmen had gained the respect of his fellow-citizens, and in 1605 he was appointed head of a section in the Pelican quarter. He seems to have acquitted himself honourably in this office, for in 1620 he was re-elected. He was a man of education, to judge by the firmness of his handwriting as displayed in his signature. He, and his eldest son after him, signed themselves van Ryn (of the Rhine), and following their example, Rembrandt added this designation to his monogram on many of his youthful works. In final proof of the family prosperity, we may mention their ownership of a burial-place in the Church of St Peter, near the pulpit.

No record of Rembrandt’s early youth has come down to us, but we may be sure that his religious instruction was the object of his mother’s special care, and that she strove to instil into her son the faith and moral principles that formed her own rule of life. Among the many portraits of her painted or etched by Rembrandt, the greater number represent her either with the Bible in her hand, or close beside her. The passages she read, the stories she recounted to him from her favourite book, made a deep and vivid impression on the child, and in later life he sought subjects for his works mainly in the sacred writings. Calligraphy in those days was, with the elements of grammar, looked upon as a very important branch of education. Rembrandt learnt to write his own language fairly correctly, as we learn from the few letters by him still existing. Their orthography is not faultier than that of many of his most distinguished contemporaries. His handwriting is very legible, and has even certain elegance, and the clearness of some of his signatures does credit to his childhood lessons. With a view, however, to his further advancement, Rembrandt’s parents had enrolled him among the students of Latin literature at the university. The boy proved but an indifferent scholar. He seems to have had little taste for reading, to judge by the small number of books to be found in the inventory of his effects in later life.

Great as was his delight in painting, pleasures even more congenial were found in the countryside surrounding Leyden, and Rembrandt was never at a loss in hours of relaxation. Though of a tender and affectionate disposition, he was always somewhat unsociable, preferring to observe from a distance, and to live apart, after a fashion of his own. That love of the country which increased with years manifested itself early with him. Rembrandt’s parents, recognising his disinclination for letters and his pronounced aptitude for painting, decided to remove him from the Latin school. Renouncing the career they had themselves marked out for him, they consented to his own choice of a vocation when he was about fifteen years old. His rapid progress in his new course was soon to gratify the ambitions of his family more abundantly than they had ever hoped.

Leyden offered few facilities to the art student at that period. Painting, after a brief spell of splendour and activity, had given place to science and letters. A first attempt to found a Guild of St Luke there in 1610 had proved abortive, though Leyden’s neighbours, the Hague, Delft, and Haarlem, reckoned many masters of distinction among the members of their respective companies. Rembrandt’s parents, however, considered him too young to leave them, and decided that his apprenticeship should be passed in his native place. An intimacy of long standing, and perhaps some tie of kinship, determined their choice of master. They fixed upon an artist, Jacob van Swanenburch, now almost forgotten, but greatly esteemed by his contemporaries.

Though Rembrandt could learn little beyond the first principles of his art from such a teacher, he was treated by Swanenburch with a kindness not always met with by such youthful probationers. The conditions of apprenticeship were often very rigorous; the contracts signed by pupils entailed absolute servitude, and exposed them in some hands to treatment which the less long-suffering among them evaded by flight. But Swanenburch belonged by birth to the aristocracy of his native city. During Rembrandt's three years in his trust, his progress was such that all fellow-citizens interested in his future “were amazed, and foresaw the glorious career that awaited him”.

His noviciate over, Rembrandt had nothing further to learn from Swanenburch, and he was now of an age to quit his father’s house. His parents agreed that he should leave them, and perfect himself in a more important art-centre. They chose Amsterdam, and a master in Pieter Lastman, a very well-known painter at that time. In his studio, methods of instruction much akin to those adopted by Swanenburch were in vogue, though the personal talent modifying them was of a far higher order. Lastman was, in fact, a member of the same band of Italianates, who had gravitated round Elsheimer in Rome.

When Rembrandt entered Lastman’s atelier, the master was at the zenith of his fame. His contemporaries lauded him to the skies, proclaiming him the Phoenix and the Apelles of the age. He was further held to be one of the best experts of Italian art, and as this had begun to find favour in Holland, he was often called upon to assess the value of pictures for sales or inventories. His house was a popular one, and his young pupil was doubtless brought into contact with famous artists and other persons of distinction. Such intercourse must have been of great value to him, enlarging his mind and developing his powers of observation.

Rembrandt spent but a short time in Lastman’s studio. Lastman, though greatly superior to Swanenburch, had all the vices of the Italianates. His mediocre art was, in fact, a compromise between the Italian and the Dutch ideal. Without attaining the style of the one or the sincerity of the other, and with no marked originality in his methods, he continued those attempts to fuse the unfusible in which his predecessors had exhausted themselves. To Rembrandt’s single-minded temperament such a system was thoroughly repugnant. His natural instincts and love of truth rebelled against it. Italy was the one theme of his master, that Italy which the pupil knew not, and was never to know. But he saw everywhere around him things teeming with interest for him, things which appealed to his artistic soul in language more intimate and direct than that of his teacher. His own love of nature was less sophisticated; he saw in her beauties at once deeper and less complex. He longed to study her as she was, away from the so-called intermediaries which obscured his vision and falsified the truth of his impressions.

It may be also that exile from the home he loved so dearly became more and more painful to Rembrandt. He longed for his own people; the spirit of independence was stirring within him, and he felt that he had little to gain from further teaching.

Self-Portrait, c. 1628. Oil on wood, 22.6 x 18.7 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Self-Portrait, c. 1629. Oil on wood, 38 x 31 cm. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

Self-Portrait, Aged Twenty-Three, 1629. Oil on wood, 89.7 x 73.5 cm. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

Self-Portrait, c. 1630. Oil on copper, 15.5 x 12.2 cm. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm.

Self-Portrait, 1632. Oil on wood, 63.5 x 46.3 cm. The Burrell Collection, Glasgow.

First Works Done in Leyden

The return of one so beloved by his family as Rembrandt was naturally hailed with joy in the home circle. But happy as he was to find himself thus welcomed, he had no intention of living idly under his father’s roof, and at once set resolutely to work. He had thrown off a yoke that had become irksome to him. Henceforth he had to seek guidance from himself alone, choosing his own path at his own risk. How did he employ himself on his arrival at Leyden, and what were the fruits of that initial period? Nothing is known on these points, and up to the present time no work by Rembrandt of earlier date than 1627 has been discovered. It must also be admitted that his first pictures for the works of this date are paintings and give little presage of future greatness, scarcely indicating the character of his genius. But amidst the evidence of youthful inexperience in these somewhat hasty works, we note details of great significance.

St Paul in Prison bears the date 1627, together with the signature and monogram here reproduced. On examining the pale sunbeam, the serious countenance of the meditation, and St Paul pausing, pen in hand, to find the right expression for his thought, his earnest gaze and contemplative attitude, we recognise something beyond the conception of a commonplace beginner. We discern evidence of careful observation which Rembrandt in the full possession of his powers would, no doubt, have turned to higher account; but even with the imperfect means at his command, he produces a striking effect. The patient and accurate execution of accessories such as the straw, the great iron sword, and the books by the apostle’s side, betokens a conscientious artist, who had applied to nature for such help as she could give him.

The Money Changer(orThe Parable of the Rich Man) bears the same date, 1627, with a monogram formed from the initials of the name ‘Rembrandt Harmensz’. An old man, seated at a table littered with parchments, ledgers, and money-bags, holds in his left hand a candle, the flame of which he shades with his right, and carefully examines a doubtful coin.

Here the brushwork is somewhat heavy, and the piles of scrawled and dusty papers give an incoherent look to the composition. On the other hand, the light and the values are happily distributed and truthfully rendered. The general tone is rather yellow and monotonous, but the colour-scheme is subdued with a view to the general effect by a deliberate deadening and neutralising of tints such as the green and violet of the table-cloth and mantle. The impasto is somewhat loaded in the lights, and has been reduced in places and apparently scraped down to avoid too startling a contrast with the shadows, where the brushwork is so slight as to reveal the transparent browns of the ground. Unlike Elsheimer and Honthorst, who in treating such subjects made the actual source of light in all its intensity a chief feature of the picture, Rembrandt conceals the flame, and contents himself with rendering the light it sheds on surrounding objects. He felt that such attempts as those of his predecessors overstepped the limitations of their art and, restricting himself to such variety of light and shadow as may be won without the unpleasantness of violent contrasts, he concentrated all his powers on the delicate modelling of the old man’s head.

These were both compositions of single persons, which were possible to copy directly from nature. Two pictures of the following year, in which several figures are introduced, presented greater difficulties. He cannot be said to have overcome them. In Samson and Delilah, the composition is awkward. Like the two preceding pictures, it is painted on an oak panel, but of somewhat larger size (61.6 x 50.4 cm), and the monogram with which it is signed is slightly modified. To the interlaced initials R and H a horizontal stroke is appended, which we find on nearly all the works of this period, and which we take to be an L, signifying Leidensis or Lugdimensis. The artist continued to use it throughout his sojourn at Leyden, and abandoned it shortly after leaving his native city.

Samson lies asleep on the floor at his mistress’s feet, clad in a loose tunic of pale yellow, girt at the waist by a striped scarf of blue, white, pink, and gold. Delilah wears a robe of dull violet bordered with blue and gold, in pleasant harmony with the colours of Samson’s costume. Delilah has already shorn a handful of her lover’s locks, and turns to show them to a Philistine behind her. The latter, armed to the teeth, advances cautiously, and a comrade even less confident than he hides prudently behind the bed-curtains, showing only his helmeted head and naked sword. Though the arrangement of the three figures in a line betrays the inexperience of youth, the handling has become broader and more subtle, and we note an increased sense of harmony. The figures are placed in frank relief against the yellow background of the floor and wall, and the brilliant effect of the sunlight that falls on the woman’s breast and robe, and on Samson’s tunic, is heightened by the dark shadows to the right of the picture. A characteristic detail of frequent occurrence in later works may be noted: among the locks in Delilah’s hand are two or three strands drawn with the butt-end of the brush upon the moist paint.

The same touch of unsophistication in the handling, the same violent contrasts of light and shadow, are apparent in Simeon and Hannah in the Temple. It is signed with Rembrandt’s name in full, and is not dated, but may, we think, be given to this period. The Infant Jesus on Simeon’s lap is strangely rigid and wooden; the composition, however, is better balanced, and the group of persons kneeling before a window is crowned in a very happy fashion by the erect figure of the Prophetess Anna. The golden and russet tones harmonise well with the blue robe of the Virgin, and the sentiment of the scene is adequately expressed. As in the preceding works, the pantomime is vigorous to the verge of exaggeration. The young man’s robust good sense made him anxious beyond measure to be comprehensible, and to preserve life and reality in the suggestion of action. Though his gestures are apt to become over-emphatic and his characters vulgar, his purpose is always clearly set forth and there is no mistaking his meaning. With time, he learnt to render his thought by more subtle and varied methods, without any loss to his directness of expression.

Self-Portrait, 1629. Etching, 17.4 x 15.4 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Self-Portrait with Mouth Open, 1628-1629. Drawing pen with brown ink and grey wash, 12.2 x 9.5 cm. British Museum, London.

Old Woman Sitting, 1635-1637. Sanguine, 23.7 x 15.7 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Rembrandt’s Mother Sitting near a Table, 2nd state, c. 1631. Etching and burin, 14.9 x 13.1 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Artist in His Studio, c. 1628. Oil on wood, 24.8 x 31.7 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

That fidelity to the living model and knowledge of chiaroscuro, of which traces are to be found even in these early works, Rembrandt acquired after a fashion of his own, by direct studies from nature – studies which were powerfully to affect his development. Models were very scarce in Holland in this period, especially in Leyden, which, unlike Haarlem, possessed no Academy of Painting. But means are never wanting to the artist really eager for instruction, and neither will nor intelligence was at fault in Rembrandt’s case. Instead of looking abroad for means of improvement, the young master made them for himself. He determined to be his own model, and to enlist the services of his father, mother, and relatives. By dedicating the first fruits of his talents to them, he secured a group of sitters whose patience was inexhaustible. Pleased to be of use to him, they fell in with every fresh caprice, and lent themselves to all varieties of experiment. Rembrandt turned their complaisance to good account. Inspired by a passionate devotion to his art, he studied with such ardour that, to quote the words of Houbraken, “he never left his work in his father’s house as long as daylight lasted.”

To this period must be assigned several little studies of heads on panel, which have only lately been restored to Rembrandt. The attribution was long contested. It was irreconcilable with established theories, and the works themselves had little in common with others following closely upon them. The first of the series (p.*), though without date or signature, is undoubtedly by Rembrandt, and may be bracketed with the St Paul in Prison as one of his earliest pictures. It is a portrait of the painter at about twenty or twenty-one years old. The face, turned three-quarters to the right, is broad and massive and stands out in strong relief against a light background of grey-blue. The sunlight falls full on the neck, ear, and right cheek; the forehead, eyes, and the whole of the left side are in deep shadow. A narrow strip of white shirt appears above the brown dress. The ruddy complexion, full nose, and sturdy neck, the parted lips, above which a soft down is visible, the unruly hair, all speak of health and vigour. The figure in its robust simplicity is that of a young peasant. The broad and summary execution emphasises this impression; the touch is free and fat, and, as in the Samson in Berlin, the hair is drawn with clashing strokes of the brush handle. The eyes, though barely visible through the shadow, seem to gaze with singular penetration at the spectator. The contrast of light and shadow is very pronounced, but the transition is skilfully effected by the use of an intermediate tone, and all hardness is thus avoided.

The portrait in the German National Museum, though probably of the same period as these, is by far the best and most interesting of the series. Here Rembrandt has evidently put forth all his strength, anxious not only to produce a faithful likeness, but to display the experience gained by recent study in a carefully considered work. As in the preceding examples, the head, turned three-quarters to the spectator and illumined by a strong light from the left, is set against a neutral grey background of medium value. The carnations are very brilliant, and are modelled with extreme skill in a full impasto, following the surfaces as we shall encounter more and more in Rembrandt’s practice. The shadows, though intense, preserve their transparency. A dark grey dress and a somewhat crumpled white collar turned over a steel gorget blend into pleasant harmony with the head. There is much distinction in the bearing and great elegance in the dress. The features are irregular, but the fresh lips seem about to open. The small eyes gaze from under their prominent brows with a frank fearlessness, while between them we already see that vertical fold which habits of ceaseless observation deepened more and more as years went by. This youthful head, crowned by the flowing hair that falls in masses across the forehead, charms us by its air of health, simplicity and unstudied grace. It is instinct with power and intelligence, and with an indescribable aspect of authority, which explains the ascendency the young man was soon to obtain over the minds of his contemporaries. Simultaneously with these pictures, Rembrandt evidently produced a large number of drawings. But, unfortunately, most of these are either lost or scattered in different collections under false attributions.

Rembrandt no longer confined himself to drawing and painting; his first etchings appeared in 1628, very little later than his first pictures. As before, he took himself for a model in his etchings, and never tired of experimentation on his own person for purposes of study. It was a habit he retained throughout his career. With himself for his model, he felt even less restraint than when his relatives were his models, and this ensured an endless variety in his studies, and absolute freedom of fancy. Exact resemblance was not his aim in these works. They were studies rather than portraits. We shall therefore find great diversities in these renderings of his own features, diversities determined by the particular object he had in view at the moment. The artist’s figure is, however, so characteristic that it is impossible to mistake it. In the course of 1630 and 1631 he produced no less than twenty etched portraits of himself (for example, p.*). These were preceded by a plate bearing the date 1629, with the monogram reversed. It is an exact reproduction, both as to attitude and costume, of a drawing in the British Museum. The composition is, however, reversed. The execution of this Bust Portrait of Rembrandt is somewhat coarse and hasty; certain portions of the dress and the background appear to have been engraved with two points held together. Rembrandt himself seems to have attached little importance to the plate, which he covered with retouches and scratches.

Among the etched portraits of himself belonging to the next two years, and signed with the usual monogram, six are dated 1630. Nine others were in all probability executed in this period, bringing the total to twenty for the two years. The plates are very unequal in value and importance; some, notably the earlier ones, are mere sketches, hastily drawn on the copper, the execution uncertain or over-laborious. Others show a firmer touch and indicate marked progress. A twofold problem seems to have occupied the author. In some the study of chiaroscuro is the primary object; he seeks to render those apparent modifications which light more or less vivid, more or less oblique, produces in form, and in the intensity of shadows. The result is a whole series of such essays: the execution in most of these is very summary, but by an ingenious shifting of artificial light and a careful study of the variations due to such successive displacements, he gains a complete insight into the laws of chiaroscuro. In many of the remaining plates design is the main consideration, and light plays but a secondary part. The management of the point is firmer and more assured; the master’s grasp on nature has become closer, and he strives to render her most characteristic traits. He seeks variety in attitudes, expressions, and costumes. He drapes himself, and poses, hand on hip, before his mirror; now uncovered and dishevelled, now with a hat, a cap, a fur toque on his head. The diversity of emotion is studied from his own features: gaiety, terror, pain, sadness, concentration, satisfaction, and anger.

Bust of a Laughing Young Man or Self-Portrait Laughing, c. 1628. Oil on wood, 41.2 x 33.8 cm. Museum Het Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam.

Old Woman Praying (also known as Rembrandt’s Mother Praying), c. 1629-1630. Oil on copper, 15.5 x 12.2 cm. Residenzgalerie Salzburg, Salzburg.

An Old Woman Reading, Probably the Prophetess Hannah, 1631. Oil on wood, 60 x 48 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

A Young Man Wearing a Turban, 1631. Oil on wood, 65.3 x 51 cm. Royal Collection Trust, London.

Such experiments had, of course, their false and artificial aspects. Grimace rather than expression is suggested by many of these pensive airs, haggard eyes, affrighted looks, mouths wide with laughter, or contracted by pain. But in all such violent and factitious contrasts, Rembrandt sought the essential features of passions with great obvious effects, passions that stamp themselves plainly on the human face, and which the painter should therefore be able to render unmistakably. To this end, he forced expression to the verge of burlesque and, gradually correcting his deliberate exaggerations, he learnt to command the whole gamut of sentiment that lies between extremes, and to impress its various manifestations, from the deepest to the most transient, on the human face. From this time forward, scarcely a year passed without some souvenir, painted or engraved, of his own personality. These portraits succeeded each other so rapidly and regularly as to form a record of the gradual changes wrought by time on his appearance and on the character of his genius.

How did Rembrandt gain his knowledge of engraving? Who taught him the rudiments of the art? We do not know, and none of his biographers throw any light on the question. The name and works of Lucas, the famous engraver, a native, like himself, of Leyden, were still revered in that city, and from his youth, Rembrandt’s admiration for him was so unbounded that he was willing to make any sacrifice to become the owner of a complete set of his works. What better guide could he have sought? As his knowledge of the master increased, he must have been deeply impressed, not only by the simplicity of his methods, but by his preoccupation with those very problems which fascinated his own mind, notably the rendering of light and effects of chiaroscuro. As M. Duplessis justly observes in his History of Engraving: “No engraver prior to Lucas van Leyden had greatly concerned himself with perspective, nor had any before him shown a like anxiety so to illuminate an intricate composition as to place each figure in its right plane, each object in its right place.” Rembrandt’s genius had many analogies with that of his famous compatriot. Both were painters, as well as engravers. They had the same love of the picturesque, the same faculty of observation, the same tendency to blend familiarity with devotion in the treatment of religious themes, the same desire to make every resource of their art auxiliary to the expression of ideas.

Nor had the traditions of Lucas van Leyden died out in his native town. Publishers such as the Elzevirs gave constant employment to co-operators who produced illustrations for their books; portraits of distinguished persons, statesmen, soldiers, or men of letters, were in great demand throughout the country, and were freely produced by skilled engravers like Jacob de Gheyn, Pieter Bailly, father of the painter David Bailly, Bartolomeus Dolendo, and Willem van Swanenburch, the brother of Rembrandt’s master. It is possible that, while in Amsterdam, Rembrandt may have met a brother of Lastman’s, who was an engraver of some ability, and have received instruction from him. We may add that Rembrandt was no solitary experimentalist in his native town at the period of these early works. Several young men shared his studies, copying from the same models, attempting the same effects of chiaroscuro, and even imitating his methods of execution. Of this we have ample and decisive proof, which throws valuable light on the career of the young artist.

Rembrandt (and his workshop?), Face of an Old Man, c. 1630-1631. Oil on wood, 46.9 x 38.8 cm. Mauritshuis, The Hague.

Rembrandt’s workshop, Head of a Man Wearing a Cap, date unknown. Oil on oak, 46 x 36.8 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel, Kassel.

First Portraits of His Relatives

The most intimate among Rembrandt’s youthful friends was Jan Lievens. They were almost of the same age, and were further drawn together by community of tastes. Lievens, like Rembrandt, had returned from Lastman’s studio to his parents’ home at Leyden. Like Rembrandt, he was now in search of his vocation, a search he in fact pursued throughout his life, without any striking development of originality, for the sojourn he afterwards made in England brought him under the influence of Van Dyck. For the moment, however, working side by side with Rembrandt, and from the same models, he busied himself with those studies of light, the effects of which are to be traced in many of his pictures and etchings at this period.

A fellow-citizen of Rembrandt and of Lievens, their junior by some six or seven years, was soon to join them in their studies. This was none other than Gerard Dou, whose presence in such company is surprising enough. No less-likely fellow-student can well be imagined for Rembrandt than this master, judging merely by the special bent of his talent, his elaborate execution and minute finish. The fact that he chose Rembrandt for his master is significant, and shows the consideration already enjoyed by the latter in his native town, in spite of his extreme youth. Gerard Dou entered his studio on 14 February 1628, and remained with him until 1631. Another artist came to complete the circle at about the same period, the engraver Joris van Vliet. Van Vliet’s productions were very unbalanced, and their average merit was not high. When left to himself, his work was coarse and brutal, utterly wanting in taste, and sometimes positively ludicrous. But, living in community with Rembrandt, he reproduced many of the master’s studies and pictures, and we owe to him our knowledge of several works which have disappeared, and exist only in his engravings.

Rembrandt was the life and soul of this busy, eager group, which, as we shall see, found the most patient of models among the inmates of his father’s house. Their studies have opened the family circle to us, and enable us to become familiar with several of its members.

The two first etchings which Rembrandt dated belong to the year 1628, and are signed with what was then his usual monogram. They are both portraits of his mother, a woman of placid and venerable mien. Her hair is drawn back from a wide forehead lined with many wrinkles; from beneath brows thick and prominent as her son’s, the shrewd and kindly eyes meet those of the spectator with an expression denoting much natural benevolence, and a deep knowledge of life. We meet her again in two drawings and in three etchings, all of which may be, we think, referred to 1631, the date on two among them. In the first (p.*) the old lady sits before a table, her little wrinkled hands crossed upon her breast. She wears a black veil on her head, and a black mantle round her shoulders. The widow’s garb and the contemplative attitude proclaim the subject of her meditation. She is thinking, no doubt, of one who is no more, of that faithful companion through good days and evil, the husband she lost the year before, and buried in the family grave in St Peter’s Church on 27 April 1630. Here the portraiture is very exact. The son, already his mother’s pride, has brought all his care and tenderness to bear upon his work, and shows an evident solicitude as to the likeness. She sat again in the same year, probably a few months later. This time the result was a freer study. She is stouter, and more wrinkled. Her costume is an Oriental robe: a scarf is twisted turban-wise round her head, the ends falling on her shoulders. Two other studies, for which she also sat, follow at short intervals. In one, dating from about 1633, she is represented in her widow’s dress again. The other is dated about 1635 or 1637, and was probably executed during a visit of the mother to the son at Amsterdam, or of the son to the mother at Leyden (p.*).

Painted portraits of his mother are no less numerous. Two of these can be found at Windsor Castle and at Wilton House. They were painted about 1629-1630. The colouring in both is grey and pale, but the handling is more skilful, and the greenish blues and pale violets make up a delicate harmony. Bearing in mind Rembrandt’s practice of taking his models from members of the household, we naturally look for numerous portraits of his father among his works. But up to the present time their identification has been based merely on hypotheses more or less plausible.

Rembrandt’s father was probably the original of the Old Man with a Long Beard, wearing a fur trimmed cap, one of the best of the early plates. In my attempts to classify the studies executed by Rembrandt and his friends in this period, I was struck by the frequent appearance of a very characteristic figure, which recurs no less than nine times among the master’s engraved works, not to speak of three heads scratched upon a single plate. They were therefore all executed before the death of Rembrandt’s father.

Besides these etchings, we know of eleven paintings executed at this period, all from the same model. They represent a bald-headed old man with a thin face, long nose, bright eyes, full and rather red eyelids, and thin, compressed lips, a moustache turned up at the ends, a short beard, and a small mole on the chin. The constant recurrence of this figure, the fact that Rembrandt painted him more than once in the steel gorget and accoutrements which he himself wears in the Hague portrait, and various minor indications, seemed to me strong evidence that the sitter was Rembrandt’s father (pp.*, **, and ***).

Bust of an Old Man, 1631. Oil on wood, 59.5 x 51.2 cm. Private collection, UK.

An Old Man in Military Costume, c. 1630-1631. Oil on wood, 65 x 51 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Old Man with a Gold Chain, c. 1631. Oil on wood, 83.1 x 75.7 cm. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

Lieven Willemsz van Coppenol, 6th state, c. 1658. Etching, drypoint, and burin, 25.9 x 19 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

St Paul the Apostle, c. 1627-1629. Sanguine and off-white highlights washed with Indian ink, 23.7 x 20.1 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

St Paul at His Desk, 1628-1629. Oil on wood, 47.2 x 38 cm. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

The portrait of Rembrandt’s father in the Rijksmuseum, of around 1630, bears a forged signature, to which the date 1641 has been clumsily added. It is, in fact, a copy of an original by Rembrandt (p.*). The modelling is elaborately carried out in an impasto, not very fat, but of sufficient consistency, and the highlights are rendered with consummate boldness and precision. The yellowish carnations are relieved against a plain background of grey-green, the shadows are very simply treated, without apparent detail, and are somewhat dingy in tone. But the accurate drawing, the delicate gradation, the absolute sincerity of expression, bear witness to a profoundly conscientious study of the living model. Notwithstanding his evident anxiety to make the likeness as perfect as possible, Rembrandt amused himself by disguising his sitter in a military costume. The honest miller wears black headgear surmounted by a large red feather; a steel gorget clasps his neck. To complete the illusion, he has given his moustaches a fierce upward twirl. Thus equipped, he might be taken for some heroic survivor of the great struggle.

The artist, pleased with the conception, repeated it with very slight variations in a portrait, painted about 1631, and signed with the monogram (p.*). He shows us the same features, almost the same pose and the same costume. Two plumes adorn the cap, a black and yellow scarf is drawn over the gorget; the costume is further enriched by pearl earrings, and a heavy gold chain, from which hangs a medallion with a cross in relief. The painting has a great subtlety of execution. The greys are colder, their gradations more refined, and the shadows are more transparent. Another of Rembrandt’s etchings, incorrectly described as Philo the Jew, bears an unmistakable likeness to a little panel which passed from the Tschager collection to the Innsbruck Museum. Both are, in fact, portraits of Rembrandt’s father, and bear the usual signature, with the date 1630.

Yet another, and certainly one of the best of these portraits of Rembrandt’s father is almost an exact reproduction (reversed) of one of the etchings, the Man’s Head, full face, signed with the monogram, and dated 1630. The sitter wears the same headdress, a black velvet skull-cap and the same costume, a reddish brown robe bordered with fur, relieved by a strip of white collar. The features are the same, and reproduced with great exactness; the eyes, encircled by red lines, have the same piercing expression. The figure is a bust, rather less than life-size, seen three-quarters in profile; the light, falling upon it from the left, leaves the right side completely in shadow. The frank and dexterous modelling is carried out in a rich impasto, handled with great delicacy and knowledge of form; the treatment of the brown fur, grey beard, and moustache is very spirited, and the neutral grey of the shadows throws the brilliant lights into strong relief.

It is natural to suppose that those studies of himself, where Rembrandt was both painter and model, were made in private. We find no trace of them in the oeuvre of his fellow-workers of this period. It was not until later, in 1634, that Van Vliet reproduced the little portrait of Rembrandt. His plate is a reversed copy, marked by the somewhat truculent vigour that characterises his work. In an early picture, Gerard Dou represented his master with palette and maulstick, putting the finishing touches to a work on the easel before him. Rembrandt, in his turn, painted a portrait of Gerard Dou, if, as we believe, Dou was his model for the head of a beardless youth, signed with his initials and dated 1631 (p.*). Be this as it may, the sitter was evidently an intimate of the household, to judge by the fanciful costume with which Rembrandt bedecked him; a turban formed of a scarf entwined with pearls, a doublet with gold-embroidered collar, and a long chain set with precious stones. The light falls full on the face, where the loaded impasto of the high tones is opposed to very transparent shadows. The features and apparent age of the sitter alike point to Gerard Dou.

Other models sat for Rembrandt and Lievens who must have been members of their circle. Among these is an old man frequently painted by Lievens, of whose head Rembrandt made several drawings, and who was the subject of various plates in 1630 and 1631. The master introduced this person, probably a relative of his own, in several of his pictures, such as the Baptism of the Eunuch. He was also the model for one of the Philosophers in the Louvre. Other figures of which both artists made use for their work with the graver were a venerable-looking old woman and a man from whom Rembrandt painted the physician in his Death of the Virgin and who also appears in a plate by Lievens.

The list might be further extended, but we have sufficiently shown how numerous were the studies made in common. Among the band of fellow-workers, Rembrandt and Lievens were the two whose affinities were strongest. Both were studious, imaginative, bent on high achievements in their art. They had shown similar precocity and a similar sense of industry. From a comparison of their works in this period, we learn that they not only worked together from the same model, but often treated the same subjects, each endeavouring to solve the same problem of chiaroscuro or technique. Thus, in several studies of heads painted by Lievens at this time, we find him drawing the hair or beard in the moist paint with the butt-end of the brush, after the manner of Rembrandt.

Rembrandt’s relations with Gerard Dou were less of familiarity and equality. He was Dou’s senior and his master; the pupil listened respectfully to his instructions, inclining more and more, however, to that minute finish, which gradually became his chief preoccupation. But in these early days he had not lost all breadth in his handling, and he was a conscientious student of his craft. Van Vliet was an engraver exclusively. He attempted to reproduce and disseminate the works of Lievens and Rembrandt. He engraved several of Lievens’ pictures, among others a Jacob and Esau, and a Susanna; we are further indebted to him for our knowledge of several lost works of Rembrandt’s. Among certain studies of heads engraved by Van Vliet which bear Rembrandt’s monogram with the legend ‘inventor’, we may highlight one of a man laughing immoderately, and grimacing in a very inelegant fashion, a Man in Distress, and a Bust of an Old Man. These reproductions give some idea of style and composition, and thus have a certain claim to respect.

The Baptism of the Eunuch was another incident greatly in favour with the painters of the day. Lastman, not to mention many others, had twice painted it. It was a subject especially congenial to the Italianates and one in which they were able, under pretext of local colour, to heap on all the gorgeous accessories of the Oriental convention they loved. Rembrandt was no whit behind them in this respect; he even borrowed several details from his predecessors. The laborious care bestowed on the mise en scène is manifest in the splendid trappings of the chariot, the rich dresses of the servants, the attire of the convert and his guards, the rank luxuriance of gourds and thistles in the foreground. The figures of the Ethiopian kneeling beside the pool, the apostle pouring water on his head, and the cavalier above them, are arranged in a perpendicular line, the effect of which is disastrous to the composition. The attitude of the horseman, and the thick legs, huge neck, and extraordinary head of his charger are no less grotesque. The sole elements of congruity are found in the saintly gravity of Philip and the reverent piety of the eunuch. We may add that he returns to the subject in 1641 for one of his etchings, in which he introduces several details of the earlier work (opposite). Without eliminating the fantastic element altogether, he successfully modifies the composition with a freer and more picturesque arrangement, and is careful to preserve the expressions of the apostle and the eunuch.

St Paul in Prison, 1627. Oil on oak, 72.8 x 60.3 cm. Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart.

Philosopher in Meditation, 1632. Oil on wood, 28 x 34 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Balaam’s Ass, 1626. Oil on wood, 63 x 46.5 cm. Musée Cognacq-Jay, Paris.

The Stoning of St Stephen, 1625. Oil on canvas, 89 x 123 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, Lyon.

As far as we can judge from Van Vliet’s engravings, the Baptism of the Eunuch and Lot and His Daughters were painted at the outset of Rembrandt’s career. Both show marked analogies with the Samson and Delilah. St Jerome was later; the execution is freer and more delicate. Before painting the picture, Rembrandt made a careful study of the kneeling saint in a beautiful red chalk drawing, now in the Louvre.

The hermit, prostrate before a crucifix, is absorbed in prayer. A brilliant light falls upon his figure. Some books, an hourglass, a mat, a gourd, and a cardinal’s hat are placed beside him. To the right, an animal with a curious head, more like a huge cat than a lion, crouches at his feet. A vine laden with grapes, springing from amidst a cluster of thistles in the background, spreads its tendrils along the brick wall of the cell. Van Vliet’s etching, the best of all his works, attests the minute finish of the original, especially in the numerous accessories. We recognise the master of Gerard Dou in this picture, and the affiliation is formally demonstrated by a Hermit in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. The pupil here reproduces the St Jerome almost exactly, contenting himself with a slight modification of the pose and figure. Refining upon his master’s lessons, Dou has carried elaboration to its extreme limit.

In the Dresden picture, each strand of the mat is separately painted; the minute veinings of the bluish thistle foliage, along which a snail has left its silvery track, are carefully noted, and the wings of a tiny butterfly that has strayed into the cave are gay with innumerable tints. The harsh cold colour adds to the dryness of the pitiless execution, and brings out the poverty of all this detail, on which Dou dwells with a satisfaction that challenges admiration of his patient puerility. What was a mere means for the careful study of nature with the master, has become the essential element of the pupil’s art.

We may form some idea of the preparatory drawing for St Jerome Reading in an Italian Landscape from a fine work in excellent condition that used to belong to Rijksmuseum (p.*). It bears Rembrandt’s monogram, and the date 1630. The subject is somewhat enigmatical. We recognise the same old man with the white beard who figures in Lot and His Daughters, and in so many of the young master’s plates. As in Lot, the scene is a cave; on the horizon is a town in flames, with monuments, a great staircase, the outline of a domed temple, and, in the middle distance, houses, from which the inhabitants are flying in great haste. But in place of the jovial old wine bibber of the former picture, we have a venerable man, sitting in meditative solitude. By his side are various costly possessions, which he has no doubt snatched from imminent pillage: a purple velvet cover embroidered with gold and a golden bowl and pitcher richly chased. He seems to have fled in haste, for his feet are bare. Resting his head on his right hand, he sits lost in thought, uncertain how to act. His left hand is laid on a large folio, which Rembrandt takes care to inform us is the Bible. The episode is therefore taken from the Scriptures, but what is it, and who is the person represented?

The picture is a very attractive one, and the problematical nature of the theme adds to its interest. The impasto is moderately fat in the lights, the touch precise and mellow, light and easy, the colour most harmonious. The delicately modelled head of the old man is full of expression, and the neutral lilac tones of his furred robe are well attuned to the pale green of his tunic. These cool tones relieve the reddish brown tints of the grotto walls with its climbing plants, and the general harmony is full of distinction. A drawing in red chalk at the Hermitage shows that Rembrandt made careful preparation for this picture. It is marked by the same easy elegance that distinguishes the St Jerome drawing, and belongs to about the same period.

Landscape, as we have seen, plays but a secondary part in the works of Rembrandt so far. The picture in which it has figured most prominently hitherto is the Baptism of the Eunuch, where its feebleness certainly betrays the inadequacy of the master’s knowledge. The plants in the foreground are taken from separate studies of their various species, and grouped together in a manner far from convincing. They are excrescences in the composition, and add but little to its beauty. Rembrandt, who was anxious to use these studies, introduces them again, with even less propriety, in his St Jerome. But he probably recognised their incongruity, and his own ineptitude for their successful treatment as yet, and so abandoned them, for a time at least. Accustomed to depend on nature for his inspiration, he needed her guidance at every turn, and was lost without her. When he attempted to stand alone, he had little reason to pride himself on the result.

At a later period he made elaborate studies of lions in every variety of attitudes, but his powers were severely taxed in the rendering of St Jerome’s attendant beast. He never particularly distinguished himself in the painting of horses, but neither did he ever render them with such grotesque absurdity as in the Baptism of the Eunuch. It was essential to him to have his models always at hand as much as possible, and as, after the fashion of the day, he loved Oriental themes, he tried to surround himself with the accessories on which he relied for local colour. His slender earnings were expended in their purchase; the collector’s passion, no less than the desire for aids to his art, impelled him to add perpetually to his collections. He loved to adorn his Scriptural models with gewgaws from his wardrobes, and to furnish the interiors in which he set them from his own storerooms.

From this time forward, we repeatedly find in his pictures and etchings, and in those of his fellow-workers, accessories he had collected for use in the studio. Rich stuffs, gaily coloured scarves, a velvet cover embroidered with gold, a fur-lined mantle; or again, arms, a helmet, a shield, a huge two-handed sword, a quiver, a Javanese dagger, and the steel gorget we have so often mentioned; or jewels perhaps, and plate; a metal bowl and pitcher, pearl earrings, bracelets, gold chains which he throws round the necks of models, or with which he fastens the plumes of their headdresses. There are other articles too, less striking but not less useful; the mat, the rosary, the gourd and the hourglass of St Jerome’s cell, the folios and parchments of St Paul’s dungeon (p.*), and of the rich man’s den.

With such accessories, Rembrandt composed studies of still life, something after the manner of those pieces technically known as vanitas, which artists like Jan Davidsz de Heem and Pieter Potter were then painting in Leyden. The sober harmonies of such works pleased the men of letters, who hung them in their libraries. Rembrandt certainly painted some of these.

The Baptism of the Eunuch, 2nd state, 1641. Etching and burin with traces of drypoint, 17.7 x 21.3 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Musical Company (also known as Musical Allegory), 1626. Oil on wood, 63.5 x 48 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

The Baptism of the Eunuch, 1626. Oil on wood, 64 x 47.5 cm. Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht.

St Peter and St Paul in Conversation, 1628. Oil on wood, 72.3 x 59.5 cm. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

David with the Head of Goliath before Saul, 1627. Oil on oak, 27.5 x 39.7 cm. Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel.

First Encouragements

It is clear that the fame of Rembrandt had gradually spread among his fellow-citizens and throughout the neighbouring towns. Amateurs began to visit his studio and a connoisseur from The Hague, to whom he had been introduced, bought one of his pictures for a hundred florins, a very considerable price for the work of so young an artist. Encouraged by his first successes, Rembrandt worked with redoubled ardour, and the close of his sojourn at Leyden was marked by great productivity.

Rembrandt’s engraved work attests this fertility. He etched a large number of plates during this period, and their diversity of subject gives fresh proof of his artistic curiosity. Neglecting no opportunity for gleaning knowledge, he found sources of interest all around him, even in the most familiar scenes of humble life. The populace attracted him, and alike in marketplace and suburb, workmen and peasants seemed to him worthy of his attention. Among people of low rank, manners are simpler, and conduct less artificial. Their gestures are franker, their attitudes and expressions more natural.

Beggars play a part as considerable in the oeuvre of Rembrandt as in the history of his country. They form a category apart, and the etchings he dedicated to them nearly all date from this period of his youth. The infirm, the lame, the crooked, the crippled, follow one another in this portrait gallery of life’s unfortunates, and the aspects in which the artist has drawn them are so true, so exact, and so enduring that many might pass for life-studies from the needy loafers of our own streets. Every variety of character figures in the collection; the haggard and the corpulent, the drunken and the starving, the defiant and the lachrymose. In Rembrandt’s, on the other hand, indigence has a less jovial mien. He painted squalor as he saw it, its abject figures, its shapeless tatters. Later he turned these to account for the cripples and sufferers of every description he grouped about the healing Christ, amidst those crowds in which he did not shrink from the portrayal of every contrast and every deformity.

It was in no spirit of revolt against academic convention that the young master worked; an instinctive love of reality urged him on, almost unconsciously. The engravings of this period are marked by as great a variety in execution as in subject. Sometimes the artist plays, as it were, with the graver, covering his plate with mere scribbles, dashed off without any preliminary sketch. At others the work is carefully carried out with a fine point, and marked by the utmost facility and knowledge of effect. To this last category belong three little plates, representing subjects from Scripture, in which Rembrandt has made use of many of the popular figures he had collected. In spite of their small proportions, they foreshadow the more imposing works which were soon to follow. The Presentation in the Temple and Jesus among the Doctors are dated around 1652, 1654, and the Circumcision dated between 1624 and 1628 is similar because of the dimensions and treatment. Full of extravagances and vulgarities as they are, they show a marked individuality. The impression of sincerity is so strong that the artist seems to have been an actual spectator of the scene he depicts. The subjects had been treated again and again. But Rembrandt, with no trace of effort or research, improvises features that give them a new character.