Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- E-Book-Herausgeber: Open Borders PressHörbuch-Herausgeber: Oakhill

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

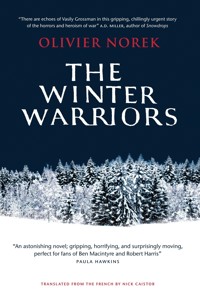

When the Soviet Union invaded Finland in November 1939, they were not expecting the Finns to fight back – much less to prevail. Olivier Norek's riveting, heart-pounding, epic historical thriller is a story of barely imaginable courage, astonishing resilience, and the best sniper the world has ever seen. `Timely, thrilling and deeply affecting … the appeal of this tour de force owes a lot to its intensity, brilliance, and ferocity, but also to a deeply moving portrait of an accidental patriot´ Independent `Impeccably researched and beautifully written, The Winter Warriors is perfect for fans of Ben Macintyre and Robert Harris´ Paula Hawkins `A novel you will not put down. Maybe never´ Richard Ford `There are echoes of Vasily Grossman in this gripping, chillingly urgent story of the horrors and heroism of war´ A.D. Miller `A fascinating and gripping novel about a forgotten corner of the Second World War. Remarkable and revelatory´ William Boyd ***Over 450,000 copies sold in French*** _____ November, 1939. A conscription officer arrives in the peaceful farming village of Rautjärvi. The Soviet Union has invaded, and for the first time in its history as an independent country, Finland is at war. Setting off into the depths of winter to face the Red Army, the small group of childhood friends recruited from Rautjärvi have no idea whether any of them will ever return home. But their unit has a secret weapon: the young sniper Simo Häyhä, whose lethal skill in the snow-bound forests of the front line will earn him the nickname `The White Death´. Drawing on the real-life figures and battles of the Finnish-Soviet Winter War, The Winter Warriors is a riveting, heart-pounding, utterly epic historical thriller from one of Europe's most acclaimed crime writers. ____ `A well-researched, heart-rending account of a tragic war´ Sunday Times `Horribly topical and wholly immersive, with descriptions vivid enough to make you shiver, this astonishing book is not only a testament to bravery and resilience, but a powerful indictment of the cruelty and needless suffering that result when ideology comes up against reality´ Guardian `Young men fighting for their country have rarely been so movingly portrayed. As the temperature falls and the body count rises, the echoes of this powerful historical page-turner can be seen in Ukraine today´ Daily Express `A sniper's life, a thriller of the highest quality, as timely as it is gripping, by a very fine writer´ Philippe Sands `Over and beyond the vivid visceral writing, character-driven narrative and a chillingly immersive atmosphere, The Winter Warriors is epic in scope. Both moving and thought-provoking, it is literary adrenaline which hooks you from page one´ Book Blast `Grim, funny, poignant, always vivid, this is the best military novel I have read for a long time´ Historical Novel Society magazine

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 479

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das Hörbuch können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

THANK YOU FOR DOWNLOADING THIS OPEN BORDERS PRESS EBOOK. OPEN BORDERS PRESS IS AN ASSOCIATE IMPRINT OF ORENDA BOOKS.

Join the Orenda Books mailing list for exclusive deals, subscriber-only content, recommended reads, updates on new releases, giveaways and more.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Thanks for reading! Open Borders Press and Team Orenda 2

345

Olivier Norek

THE WINTER WARRIORS

Translated from the French by Nick Caistor

5in memory of all the lives lost

*

This is a novel.

However, the passages of dialogue often come from archives or have been provided by enthusiasts, military sources and historians. None of the battle scenes has been invented. No act of bravery has been exaggerated. Although these events will soon have taken place a century ago, they point us to contemporary history and serve as a warning. War often takes us by surprise, and there has to be a first death on our land for us to truly believe in it.

O.N., July 2025

6For a just cause with a pure sword.

Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, Chairman of the Finnish National Defence Council, 1931–9

*

When the non-stop deadly Russian artillery fire started up, thousands of white-hot hammers echoed in the heads of the Finnish soldiers. One man giggled inanely, another wept hysterically.

Erkki Palolampi, Finnish Army Information Officer on the Kollaa front line

*

You’ve no doubt heard of Hell. It is the same here. But not even the Devil would understand what is happening here.

Soldier Tṡurkin, 150th Infantry Division, Soviet Army

Contents

First Prologue

Light streams over his closed eyes, over his prostrate body and its stilled heart.

All around him, the last day of war has littered the ground with bodies in their thousands, staining the snow red. Amongst the other corpses, he is no-one. No more precious, no more important. Elsewhere, he could be a father, a brother, a friend, a husband. Elsewhere, he is everything.

In death, only their uniforms set them apart. They were enemies, now they lie side by side. Here, hands touch; elsewhere, lifeless faces confront each other. They have spent the whole winter killing one another.

The dead from earlier weeks are half-hidden in the earth. Only vestiges remain: still visible helmets, occasionally parts of their backs. Their arms are like aerial roots, as if growing out of the ground itself, ready to rise, get to their feet, and haunt all those who decided on this war.

Their blood saturates the ground, their flesh nourishes the trees, mingles with the sap. They will be in every new leaf, every new bud.

There were more than a million of them, and when, tomorrow and beyond tomorrow, the wind blows through the branches of the forests of Finland, it will also carry their voices.

There had been happy days, a cherished peace.

There had been a before, in the days leading up to the Hell.

Second Prologue

For many years Finland belonged to someone else.

For centuries, it formed part of the kingdom of Sweden. For a further century, it came under Russia’s sovereignty. It was not until 1917 that it gained independence. 9

In 1939, therefore, Finland was 22 years old. Twenty-two years are hardly sufficient to make a man, let alone a country.

In a storm of lead and fire, Stalin’s Red Army, the largest in the world, swept through this neutral, poorly armed nation, launching a bloody conflict known by history as the Winter War.

The hellish events that are the subject of this novel took place in that year of 1939 at Kollaa in Finland. But also on its isthmus, in Karelia. On the ice fields at Petsamo. From the shores of its gulf to the distant reaches of Lapland.

Imagine a tiny country. Imagine a huge one. Now imagine them clashing.

Twenty million shells. The Earth almost cracked in two when Russia pounded its crust in the same place day after day for more than a hundred days.

Tank columns against old-fashioned rifles. A million Red Army soldiers against workers and peasants. But past conflicts tell us it takes five soldiers to face a single man fighting for his land, his home country and his own people, hands clutching his carbine, a sentinel behind the door of his barricaded farm.

And a single man can change the course of history.

*

At the heart of the harshest of its winters,

at the heart of the bloodiest war in its history,

Finland saw the birth of a legend.

The legend of Simo Häyhä, the White Death.

And yet there had once been happy days, a cherished peace.

There had been a before, in the days leading up to the Hell.

The Winter Warriors

1

The days before the Hell, a forest near Rautjärvi, a village in Finland

Crushed grass, snapped branches, tufts of fur caught on juniper bushes, prints in the soil whose pattern signposted the way taken by whatever had left them: without a sound, Simo was reading the forest.

He could hear the trees soughing in the wind, the pulse of their sap, the rustle of animals; hooves on dry leaves, their hides rubbing against bark, their hearts beating. For those who can read it, there is no noisier silence than that of the forest. Simo never forced his way in, he was always invited. Simply invited. And so as not to offend the forest, he took from it only what he needed. Sometimes an elk, at others a wolf, partridge, crow, or one of the ermine whose coveted furs had adorned all the capes of the kings of France.

To take proper aim on the Finnish Civic Guard shooting range Simo had to delve inside himself, blot out everything around him. But here in the forest he was alert to every murmur, every silence, every sound of running or flight.

Twenty metres ahead of him, a fox’s fiery coat stood out against the green needles of an ancient spruce’s drooping branches. The animal’s body pulsed slightly as it drew breath. Simo controlled his own breathing and aligned it with that of his quarry. For an instant they breathed in harmony as the young man became the animal he had in his sights, until he could sense what movements it would make. The fox sniffed the ground and the air, trying to 12discover why its instinct was warning him of danger although he could not detect the reason. He approached his earth and dropped the lifeless body of a blackbird from his muzzle. Exactly 23 metres away.

No-one is more adept than a person who has learned the skills from his father, and Simo’s father had taught him the art of judging distances, following his own peculiar teaching method.

“How far?” he would ask his young son, pointing to the burnt-out trunk of a tree struck by lightning the previous summer.

Simo told him his estimate, walked over to the trunk, counting his paces, and stood behind it.

“The bullet traces an arc. If your estimate is too short by a metre, the missile will bury itself in the ground. But if your estimate is a metre or two long, it’s going to lodge itself in your belly,” his father threatened.

Of course, the threat was never carried out. And yet, when Simo got it wrong, his father’s words were as wounding as a bullet:

“Son, you’re dead. Let’s go and eat.”

*

And so, while others were enjoying a rest after their meals, letting their bodies recover from the hard work in fields and farms, Simo donned his boots or took down his pair of skis and headed for the forest, disappearing into a primordial green that must have given birth to every other shade of green. He would roam through the trees until he chose a landmark, calculate its distance and verify this by counting the number of steps to it. He had followed the same routine every day, every week, every year from the very first time he had picked up a rifle.

“That fox. How far?” he heard his father’s voice say inside his head.

Simo gently rested his first finger on the trigger, then squeezed harder and harder … But an instant before the shot rang out 13and roused the forest, a black muzzle appeared from the earth. A female came lumbering wearily out, belly heavy with a pregnancy that curved her spine towards the ground.

Simo eased his finger on the trigger and silently backed away until he was out of sight. It would be wrong to see this as compassion. He had not spared the animals, simply postponed their meeting for a while. Being able to do something and having to do it are not the same.

To be able to shoot or to have to shoot. To be able to kill or to have to kill.

*

Back at the farm, a fat grey partridge in his bag, Simo propped his unloaded gun against the stone wall, hung his heavy cotton jacket on the rack, and sat down to a plateful of buttered sugary biscuits placed in front of him. Before eating, he let the flames from the hearth warm his back and ease the knots in his muscles. Stretched out on the flagstones, the family dog thrust its front paws forward in his dream’s imaginary chase.

“Toivo and Onni came by to see you,” his mother announced without looking up from her knitting, two long needles in her hands and her body sunk in the cushions of an armchair as old as her.

Simo shrugged. Toivo and Onni were neighbours and friends from childhood. They would see each other at some point. No hurry.

“Onni showed us his wedding ring,” his mother went on, all innocence. “He even said he’d gone down on one knee.”

In front of the kindly fire, Simo’s nieces – one knee-height and the other not much taller – were plaiting each other’s hair, pushing flowers into their blonde locks. Since the conversation was taking a turn they all knew very well, the two girls mimicked an adult voice to recite reproaches they had heard so often. 14

“Simo Matinpoika Häyhä, it’s not by spending all your days in the forest that you’ll find someone who loves you,” the first one said.

“Unless of course you want to marry a doe,” the second one said.

“Do you want to marry a doe?” they chimed in unison.

In another second the young man would have chased them round the room and made them suffer for their cheek. However much they giggled and pleaded with him, he would have untied their plaits and afterwards the day would follow its course. But at that second the father came into the kitchen and sat at the table, restoring calm simply by his presence. The girls were still laughing, and Simo gave them a warning look: he wasn’t finished with them.

The father weighed the still warm partridge in his hand. The blood around the bullet hole in the neck was already dry. Pleased with Simo’s efforts, he blew gently on the few light feathers stuck to the palm of his hand, then turned to Simo.

“Are you ready for tomorrow?”

Simo looked first at his gun and then at his father, who sought at once to erase his son’s over-confident smile.

“You must show yourself worthy of Rautjärvi, because there’ll be 1,700 against you …”

Simo’s smile only widened.

2

The following day, Finnish Civic Guard Rifle Championship, Helsinki

The strained expression on the faces of the other teams was a tribute to the squad of marksmen from Rautjärvi. Although everyone respected them, many would have preferred their truck to have had an engine problem, or for its wheels to have skidded off the road, leaving them in a ditch: any unforeseen accident that meant they did not arrive at the shooting range in time. But the engine did not fail, the wheels stayed on the road, and no obstacles got in their way.

“Perkele!1 The lads from Rautjärvi have arrived,” groaned one young man.

“Is Simo with them?” another youngster said, because the marksman’s name was what was making everybody else so anxious. Every one of the 1,700 other competitors in the national championship had uttered it at least once on the roads converging on Helsinki from all over Finland.

“I don’t know. I haven’t seen him yet.”

“The wolves and foxes never see him either. And yet his coats are made of their fur.”

“I reckon people overestimate that kid,” another team captain said, determined not to leave without a trophy.

*

Nobody had ever really doubted that Simo would win the competition. A farmer and reserve soldier like most Finnish young 16men, he was discreet and modest and scarcely taller than his rifle, but rarely gave the other competitors a chance. It was in his blood, the blood that pulsed at the end of his trigger finger, blood the same colour as the centre of the target he never missed. Never ever.

So the group around Simo had already finished their congratulations. Even the officers who had organised the event had come over, as it was one of their number who had challenged Simo:

“How often can you hit the bull’s eye in one minute?”

Simo’s look was enough to show he accepted the challenge.

Led by Onni and Toivo, the Rautjärvi team began to take bets.

Onni, the one soon to be married, whose hair was so blond the sun sometimes lent it silvery glints, held out his upturned helmet to receive the money.

Toivo, the best friend, whose perfect beauty made young girls and their mothers blush at dances, wrote the bets down with a coloured pencil on the first page of a novel he had not yet begun.

Simo was nothing more than a trainee soldier in the Civic Guard. His rival was a career officer, and so the odds naturally fell in the officer’s favour.

“Five marks on the officer. He’s an instructor. How could he be beaten?”

“I’ll add ten marks on the officer!”

“There’s no hurry, gentlemen, you will all have the chance to lose your precious money,” Toivo taunted them.

“Come on, don’t be mean, empty your pockets, I’ve got a wedding to pay for!” Onni said.

The officer to the stand. Simo to the stand.

Two hundred metres away, the new target.

The officer lay down, and the stopwatch began. The exploding gunpowder made the rifle’s muzzle rear, so that after each shot he had to realign his sights, control his breathing, then shoot again. By the sixtieth and final second, the officer had hit the bull’s eye 17fourteen times, although there was some doubt over the twelfth bullet, which some argued wasn’t altogether in the centre. The officer had found the target fourteen times with an automatic weapon that did not require reloading after every shot.

It was Simo’s turn to lie flat on the ground. The officer glanced at him, confident and condescending. What did he have to fear from this Sunday soldier, barely one metre fifty tall, who looked so babyish it seemed incongruous for him even to be holding a gun.

The murmurs among the spectators grew when they realised that, as promised, Simo would indeed be using his M28/30 manual-loading rifle, which meant he had to load a fresh round after each shot. So he had to aim, fire and deal with the recoil, just as the officer had done, but also eject the bullet case by clearing the breech, pick up another round from the ground, load it, aim, fire, control the recoil and start all over again. Simo lined up his rounds in front of him; on the signal, his dancing hands stupefied everybody fortunate enough to be present that day. The speed of his gestures, the machine-like precision, a manoeuvre he had repeated millions of times: in the permitted minute, Simo hit the bull’s eye sixteen times without a single impact being in doubt.

For a man to fire more accurately and more rapidly with a manual-loading rifle than someone with an automatic one was quite simply impossible.

At least, that was what everyone had believed until that day. The defeated officer left the stand without congratulating his adversary.

*

In the truck taking the victorious squad back to Rautjärvi, everyone was singing raucously, passing the trophy from hand to hand.

“I hope there was a Ryssäspy there today,”2 Toivo said. 18

“They’re everywhere, even under our beds,” Onni said.

“Then he’ll have seen you, Simo, and he’ll tell his friends how good we are with a weapon in our hands.”

There were shouts of “Huraa”, and Toivo shook Simo by the shoulders, even though his friend was abashed at being the centre of attention. To embarrass him further, the others began to cry “Simo! Simo!” as the trophy was returned to its place between his legs. It swayed to and fro as they drove along the bumpy roads back to their village on the Russian border. Despite the discomfort, many of them fell asleep, heads resting on their neighbour’s shoulder.

Toivo, who was still wide awake, whispered: “My cousin in the army came to visit. He said their headquarters had forbidden all officers to take leave until further notice. He also said we’re going back to the defensive lines on the border, to strengthen them.”

“Again? We did that only last summer!” Onni protested. “Haven’t the Russians asked us to abandon them?”

“And if they ask you to abandon your wife, will you do it?”

“I hope they at least give me time to marry her! But ask me again in a few years, and perhaps I’ll go myself and dump her in Moscow!”

*

At nightfall, the Rautjärvi team jumped down from the truck in the middle of their village, saying goodbye to one another as they reached their homes. Eventually only Simo and Toivo were left.

From first light the next morning, at an hour when only peasants are out of bed, the Finns would return to their fields and farms. Men and women, foreheads bathed in sweat, were building a country that was prospering. Even though there were still some well-off families and rich individuals, there were few who allowed themselves the kind of bourgeois lifestyle found in wealthier 19countries. Finland had only been independent a little more than 20 years, and everything was still to be done.

This meant the only leisure activity for young peasants and workers was the Civic Guard. In town and country, they were taught the history of Finland, and how to defend it. They were taught the ideal of the patriotic Finnish male, with a virile body and educated mind. But perhaps above all, enrolling in the Civic Guard gave these youngsters the chance to broaden their minds and travel round the country on military exercises or for rifle competitions.

In a country desiring only peace, they were also taught the art of war, and both in the village and their Civic Guard regiment, Toivo and Simo were united by an unbreakable bond.

“See you when I see you, and the sooner the better,” Toivo said, taking Simo’s hand.

Simo repeated the same, and the friends parted.

Simo Häyhä in the Finnish Civil Guard, c.1922

3

Before it was plunged into terror, nature had chosen to pamper Finland with the most beautiful summer. The hay had grown in leaps and bounds; harvests had been abundant. The sun shone by day and the rain fell at night, without ever getting in each other’s way.

Toivo was with his cousin, a career military man. They were sitting in the shade of a big rock, gorging on the red and black bilberries and whortleberries. Lips still stained, his cousin lit a cigarette and they shared it, gazing out over the fields of barley awaiting the autumn harvest. There were rumours circulating in the countryside, at the mill where wheat was taken to be ground, at the market stalls and in factories. Rumours of a possible war. Some believed them. Others thought war was unthinkable. Toivo could not make up his mind, and was hoping his cousin could clarify matters.

“Finland has never been a threat to Russia. So why would Stalin be so scared he would threaten to invade us?”

“He couldn’t care less about our pitchforks,” his cousin assured him, in a cloud of cigarette smoke. “It’s the Third Reich that keeps him awake at night. If Hitler wants to attack Leningrad, he’ll only have to march from Berlin through the neutral countries – Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland – sweep down our coast, cross the isthmus of Karelia, and Nazi Germany will be in Russian territory without having fired a shot. Stalin isn’t afraid of Finland; he’s afraid that Finland will do nothing if Hitler invades us.” 21

He spat out a strand of tobacco sticking to his lip before passing the cigarette to Toivo. He went on:

“Why do you reckon Stalin is asking us to hand over entire regions and allow him to station his troops on our territory? Making war outside his own country is far easier, if you ask me. Our government is about to mobilise all professional soldiers, the reservists and the civic guardsmen, in order to reinforce our defences on the Russian border. We’ll be told it’s a special military operation, nothing more than an exercise to test our readiness. It reminds me of those animals that farmers fatten up. They must think we’re very kind to feed them so well, until their throats are cut.”

“Do you really think they’d prepare us for war without telling us?”

“What I really think is that if Finland and Russia come to blows, it won’t have much to do with our side. Everything will come from Moscow. I also think you and your friends should make the most of the end of summer, Toivo.”

4

The Kremlin, Moscow

Woken in the middle of the night, the colonel was now in the Kremlin’s Great Palace, sitting stiffly in his dress uniform on a carved gilded chair in a corridor as long and wide as a street, lined with white columns beneath a painted ceiling with a row of chandeliers that could hold as many as a thousand candles.

Sitting there, his face crumpled, and with maps rolled up on his thigh, the colonel had been roused from sleep by fists thumping on his door.

“I have no idea,” he told his worried wife.

For two years, Stalin had embarked on a massacre in his own country. His insistence on Western conspiracies and internal betrayals, fed by his acute paranoia, had led him to despatch more than ten million of his fellow countrymen to the gulags, and to kill a million more with a bullet to the back of the head. It was a period of history that would forever be known as the Great Purge.

Consequently, however many awards or medals one had, there was always great trepidation when you were summoned in the early hours to the Kremlin.

“Go to your sister’s,” he told his wife, kissing her hands. “I’ll find you there.”

An hour later and the colonel was none the wiser. As he felt for his fob watch in his inside pocket, a poorly fixed medal came loose from his chest and clattered to the floor. The metallic echo reverberated down the immense corridor, making him feel yet more alone and tiny, despite his rank. 23

A door opened in the distance. The guard took a whole minute to reach him, approaching steadily, heels clacking on the polished wooden parquet.

Invited to follow the man, the colonel hastily gathered his things under his arm and strode after him. He noticed a clock above the huge double doors that closed behind the guard, leaving him once more on his own in a meeting room into which a school or a theatre could have fitted, and across it a table where two weddings could have been celebrated.

The colonel heard the voice of Vyacheslav Molotov, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, long before he saw him enter the room.

“Colonel Tikhomirov, thank you for coming.”

Wearing a pair of small oval spectacles, with a round, amiable-looking face and well-trimmed moustache, Molotov sat down at one end of the table. Tikhomirov still had no idea why he had been summoned. Congratulations for his unswerving loyalty? Not at this time of night. A bullet to the head? In those years, a rumour could condemn you as surely as a cancer, but why call him to the Kremlin when the deed could be done in a discreet alleyway or out in the countryside?

“Are we expecting more people?” the colonel asked, uneasy at being all alone.

“No. And this meeting must never be referred to. I need six men for a mission of the utmost importance. A driver, a gunner and four soldiers. Only nine of us will know about this operation. You, me, the six men you choose, and Comrade Stalin, of course.”

No congratulations then. No execution either. Tikhomirov felt jubilantly alive, and promised himself to find the time to watch the sunrise.

Still standing to attention, the colonel assured Molotov: “I’ll find you the very best among our elite men.” 24

“No, that will not be necessary. Have you ever visited the gulag at Belomorkanal?”

Before the colonel could envisage this question as a threat, Molotov said:

“Don’t worry. I’m sending you there because that’s where your mission begins. If Finland continues to refuse our demands to annex territory, they will have to declare war on us.”

“War? Against us?” Tikhomirov was astonished. “I don’t think they have the means. Or any wish to do so. It would be suicidal, to say the least. Why would they contemplate so rash an act?”

“Because we’re going to force them to,” Molotov said with a smile.

5

Finnish National Defence Council, 21 Korkeavuorenkatu, Helsinki

As chairman of the Finnish National Defence Council, Carl Gustaf Mannerheim cut an improbable figure. In his seventies, tall and rangy with a prominent moustache and a lively, penetrating gaze, he looked more like a dandy or a Conan Doyle private detective.

Having married the daughter of a general to advance his career, he had been a wretched husband until their divorce, but his two daughters made a good father out of him. A loving, protective father. Escaping a Finland that had the same opinion of homosexual women as much of the rest of Europe, Anastasia had settled in Paris, her sister Sophie in London. In these capital cities that they hoped were more enlightened, they could live and love freely. And it was to the Parisian Anastasia, living far from the threats looming over her native country, and to her alone, that Mannerheim could confess his despondency.

I am going to tender my resignation to the President once more, as nobody seems willing to listen to me. And if they won’t listen, they should at least understand Stalin’s demands. If he wants part of our country, a port or a military base, if he wants to station soldiers on our territory to guard against the rise of the Third Reich and his fears over an Adolfus who is marching across Europe, let him have his way! I was a soldier of the Tsar when Finland still belonged to Russia, and know how determined they are. I know them better than they do26themselves. We ought to give way a little so as not to lose everything. Because here we are in the middle: innocent, vulnerable, busily preparing for the Olympic Games – the place for noble competition, as our President constantly reminds us. But competition is not war, and I’ve never seen any nobility in war. Not to heed Stalin’s demands is unwise. Not to foresee his anger is a huge blunder. Yes, we’re stuck in the middle between Eagle and Bear, protected by our neutrality, but that’s a very weak shield. We seem to think the storm will pass without us getting wet. Ragnarök is on its way, I can feel it. And if our future means war, we’re not ready for it, of that I’m sure.

Mannerheim read this through, massaging the hand crushed many years earlier by an old nag weighing half a ton, an accident that meant he was forced to write in a curious manner, his fingers holding the pen like a pair of sugar tongs.

Surrounding this perplexed head of the Finnish armed forces, scarcely leaving room for the few paintings hanging from the walls, 7,000 volumes of books on history and geography were stacked in a library too heavy ever to be moved. Carl Gustaf Mannerheim knew that the decisions his government was about to take would write the history of his country in the pages of the national novel that would one day find its way into this very library. His name would appear there. It remained to be seen what would be said of him, and what Finland would be remembered for – if it still existed, that is.

He signed the letter “Gustaf”, as he did all his personal correspondence. He was laying down his pen when the office door opened: it was Aksel Airo, a former cadet at Saint-Cyr military academy in France. His most trusted assistant.

“Is the Ghost ready?” the field marshal said, picking up his baton.

6

Aksel Airo made Mannerheim wait by the side of the 1915 Rolls Royce Silver Ghost convertible, the field marshal’s official car. A shiny black and powerful panther, with leather seats and walnut trim, two gigantic headlights and a streamlined body, the car would make even the most timid of drivers look impressive.

In front of them, an officer was checking that the sub-machine guns in the boot were loaded, while another was peering underneath the chassis to make sure there was no bomb.

“Is this really necessary?” Mannerheim said impatiently.

“Cars have been blown up.”

“You listen to the radio too much, my friend.”

“You’re protecting Finland. Let me protect you.”

“I’m protecting Finland,” the field marshal repeated to himself. “That’s amusing. Don’t tell anyone, but I have absolutely no idea how to get us out of this mess.”

“I find that hard to believe.”

“If we give way to Stalin by offering him territory, I’m afraid he’ll only want more. And then make the whole of Finland as Russian as it was hitherto.”

“That’s why you are also preparing the country for war.”

“A war we will be certain to lose. So if we give way we will lose; if we fight, we will perish.”

For weeks now Mannerheim had been living with two radically opposed states of mind: a diplomat searching for peace; a military leader preparing for a deadly conflict. He was both at the same time. Airo took a seat next to him in the now inspected Rolls Royce. 28

“While we’re still negotiating, I don’t think there’ll be any warlike move,” Airo said. “Stalin would never dare to fire the first shot, especially on an independent country.”

“Ukraine, too, wanted its independence. And he starved it. Four million dead can testify to that. Are you sure your reading of the situation is correct? I don’t know how he’ll do it, but if Stalin wants to move against Finland, he’ll find an excuse.”

On its way to the Esplanadi quays where they had a meeting with the president in his palace, the Rolls Royce did not go unnoticed: Mannerheim and Airo in the rear, and in front of them, next to the driver, their escort, who kept a tight hold of the loaded gun on his lap. Mannerheim searched in his jacket pocket.

“Here are two letters and some money. One for Paris, the other for London.”

“Money? But you sent your daughters some only last week,” said an astonished Aksel.

“The future looks grim. I prefer to be prepared.”

“So you really believe there will be a war?”

Mannerheim believed it so strongly it kept him awake at night. And whether you worried about the ambitions of a greater Russia or feared an attack by the Nazis, Finland was caught in the middle.

“That would be a catastrophe,” Mannerheim admitted. “If the negotiations fail, we’ll exhaust all our wealth on the battlefield. The day will come when we’ll be forced to ask married couples to melt down their wedding rings to recover the gold and silver.”

Hearing this, Aksel Airo instinctively twisted the gold ring on his finger. He thought of his wife Wilhelmina and his two daughters, Aila and Anja. Debate with words, beat with fists. Once the very last words had been uttered, the last hopes for peace exhausted, that would leave only weapons. Both at the front and in the rearguard, nobody in Finland would be safe any more.

“I am sure we can still avoid it,” Airo said, to reassure himself.

“What do you think I spend my days and nights trying to do?” 29

“I know, Field Marshal. I do the same.”

The Silver Ghost came to a halt, but nobody got out.

“Are you ready?”

The future of Finland was at stake in this meeting.

“I’m too old to shilly-shally. Either the president allows me to mobilise my soldiers, or I resign.”

7

The president had listened, and Mannerheim had not resigned. And so as the field marshal had envisaged, a general mobilisation for defensive purposes had been ordered. And yet not even Mannerheim liked the idea. It left a bitter taste, and was a cruel, underhand strategy. But he accepted he would not be able to hold his head up high if it came to war.

“Make a company of soldiers out of the sons of the same village, then on the battlefield there will be brothers, friends, neighbours, so that they will have what they must defend before their eyes. It will not be people they do not know dying next to them, it will not be strangers whose lives they will want to save. They will have no choice but to fight, because who would dare to desert when his brother is calling for help?”

*

Like blood coursing through the veins, emissaries travelled along every road in Finland. On horseback, in cars, on bikes, on foot and by boat. No farm was ignored, even if it was surrounded by lakes or marshes. No reservist or able-bodied member of the Civic Guard was spared.

Pietari, with the jet-black hair that was almost unknown in Finland, heard the spluttering old car even before he saw it. He closed the door to his little red-painted farmhouse with its white-framed windows, rolled the grass stalk he was chewing to the corner of his mouth, and folded his arms determinedly.

“Pietari Koskinen?” the visitor said, rummaging in his bulging satchel as he jumped out of his vehicle. 31

“You know who I am. We’ve met in the Civic Guard,” Pietari said as gruffly as if he was telling a stranger to get off his land.

The messenger did not come any closer, warned not only by Pietari’s coal-black hair but also by his face as angular as a badly knapped flint and thin, razor-sharp lips that looked as if they never broadened into a smile.

“I’m sorry, I’ve been told to check everybody’s identity. I have your call-up papers here. For your younger brother Viktor as well.”

Pietari looked back at his house, checking it was still silent.

“Viktor is dead,” he flung back at the man. “Of sunstroke. During the harvest.”

The emissary looked at him disbelievingly and took out two letters.

“You mean Viktor Koskinen? The one I saw at the village celebrations a few days ago? I didn’t know the dead danced so well.”

Fists clenched, Pietari swallowed his lie. Inside the farmhouse, hidden by the lace curtains, Viktor was listening intently through the half-open window.

“I’m sorry, Pietari. All able-bodied men who have undergone military training must take part in these special manoeuvres.”

“You know very well what these manoeuvres are. You know why we’re being sent down there.”

From first light, the emissary had personally handed this same bad news to heads of families, young married men, and others barely adult. Like Viktor.

Finland was divided in two. One half still refused to believe in Russian aggression and saw this mobilisation as no more than a military exercise of the kind organised once or twice a year. They received the messenger impatiently, keen to be of service to their country. The other half showed more reluctance, not to say frank suspicion, and hands had often trembled as they took the letter. Two of those called up had even run off into the woods, but to 32no avail. They could not stay hiding forever, and even before they joined their regiment they would face disciplinary sanctions.

“Orders are orders. So unless someone is an invalid, gravely ill, or too old, there is no excuse.”

Pietari repeated the words in his head. Viktor was not old or sick. Unfortunately.

“Give me a minute.”

Pietari soon came out of the small tool shed grasping the long wooden handle of a sledgehammer. Without a word, he walked past the messenger. Tapping his clogs against the house wall to remove the mud, he disappeared inside.

To refuse to run the risk of getting a bullet in your hide shows not so much a lack of courage as plain common sense, so Pietari did not feel ashamed when he laid eyes on his younger brother crouching terrified in a corner of the room. Sweeping aside the plates and cutlery already laid for lunch on the big kitchen table, he took down a still damp washing-up cloth and held it out to his brother.

“Bite on this. And put your hand on the table.”

The hammer rose above Pietari’s head and, with all the love he had for his younger brother, he crushed three fingers with one blow.

The scream penetrated the house’s thick walls. The messenger wrote in pencil on his list: Viktor Koskinen. Invalid.

*

His automobile took him to the next farm. He knocked on the door. For the first time that day, he was certain the young man who lived here would not run away or receive him with a heavy heart.

Adjusting the satchel on his shoulder, he greeted the woman who came to the door: “Good day, madam.”

“Hei,” she answered briefly, kitchen knife in hand, its broad blade stained with a rabbit’s warm blood. 33

“I’ve come to see your son. I have his call-up papers.”

She had had five sons, and four of them had already made her weep. Antti had disappeared in a war more than 20 years earlier; Juhana was injured in that same war. Tuomas had been felled by sunstroke on a building site, and Matti had left one day, never to be heard of again. The call-up must be for her youngest, the only one left. The peasant woman became a wolf.

“On koira haudettuna with your story of a military exercise,”3 she said suspiciously.

“I’m only obeying orders.”

“If my son doesn’t return, remember that I know where you live.”

“I’ve been threatened like that all day,” the messenger said with an unconcerned smile. “The Javanainen family promised to drown me if the six brothers did not all come back, and the Lankinens will take me behind the sauna if their three brothers are not there for Christmas.4 But if there is to be a war, and if a man like your son doesn’t come back from it, there’s not much hope for the rest of us.”

With a quick flick of her wrist, the woman cleaned the blood from her knife, sending a scarlet jet that streaked the threshold and ended up on the tip of the messenger’s boots. He concluded that if her son had half the spirit his mother had …

“You’ll find Simo in the barn. He’s already preparing his things.”

*

Late on the same day, the car pulled up on the drive to a house encircled by a river. Leena was washing mud and sweat from her laundry in its clear water. When she raised her head to ease her neck muscles, she saw her father deep in conversation with a young man carrying a satchel.

Loosening her hair, Leena wiped her hands on her long dress and left her washing on the riverbank to go and join them. It was 34only when she drew closer that she saw the bundle of banknotes in her father’s hand, the letter in the visitor’s, and heard snatches of their conversation.

“This is not about money,” said the stranger, raising his hand in front of his face to show his refusal.

“It’s always about money! How much more do you want?”

As if caught out, when her protective father saw Leena he stuffed the small bundle into his pocket, and the messenger could finally address the person he had come to see.

“Leena Aalto?”

“Who is asking?” she challenged him.

“I have your call-up papers.”

The father lowered his eyes, acknowledging his defeat; when she read her name, the young woman’s face lit up.

8

Onni found Simo by the fence next to the Häyhä family’s stables. He had hay on the end of his pitchfork, clogs on his feet, and sweat on his brow.

Having also received his call-up papers, Onni was one of those not in the least concerned about it. He and Simo talked about the weather, the harvests and the latest comedy featuring the national clown Lapatossu,5 advertised at the local cinema. The comic actor was even more popular now that sound had been added to the images in a film. The two of them talked about Onni’s wedding, which should have taken place at the end of August, but which had been postponed on several people’s advice until a time when relations with Russia were less tense. September had given way to October; August was a long way behind them, and if the event was delayed much longer, Onni feared he would have to go to church on skis, he in his brand-new suit, and his bride-to-be in her beautiful white dress. That would be a great shame, because in fine weather Finland was a magical country, the perfect setting for a wedding.

Those summers when daylight lasts for eighteen hours and the sun constantly skims the horizon, as if too heavy to climb to its zenith, when bodies cast giant shadows, and you can read in the middle of the night or, with a bit of effort, sunbathe at four in the morning. On one of these never-ending days, the couple would have said their vows, got drunk, eaten more than they should have, bathed in one of the 180,000 lakes in Finland, and danced in the light at midnight, casting their elongated shadows on the 36surrounding houses like a dance of merry spectres come to celebrate their happiness.

The chaotic international situation had dealt a blow to this joyful wedding. But while Onni was complaining about it, something else was on his friend Simo’s mind.

He disappeared into his house, painted the colour of wheat as though to harmonise with nature. When he reappeared he was carrying two glasses of fresh milk, and had a long case under his arm.

“For me?” Onni said, astonished.

Simo had been counting on giving it to him on his wedding day, but was afraid that what their government had termed a “mobilisation for special manoeuvres” was in fact a call-up for war, which was something not everyone returned from. Onni opened the case and whistled through his teeth.

“Your very first rifle? The Westinghouse? Are you sure?”

Simo patted him on the shoulder to confirm it was something he had thought through. The defence budget never having been a national priority, not all the reservists and Civic Guards had their own weapon. Even army uniforms were not complete: casual trousers were worn with military jackets, uniforms with everyday shoes, and the blue-and-white Finnish insignia was worn on woollen caps, a motley mixture of war and peace.

As the best marksman in the Rautjärvi Civic Guard, Simo had his own M28/30. Toivo, who was no slouch himself, had his own M/91 Mosin Nagant. Onni, though, was empty-handed. Now Simo was arming his comrade for whatever the future might hold. And Onni had seen it as nothing more than a wedding gift, whenever that was finally celebrated.

9

Leena Aalto presented a problem for her parents. In fact, they did not really have much to complain about, except that she was a Lotta.

“Lotta”. As a child, Leena had heard this name in passing, and her mother had satisfied her curiosity.

“Her name was Svärd, Lotta Svärd. A long time ago, Finland belonged to Sweden, and when more than a century ago Sweden fought against Russia, we were dragged into the war alongside the Swedes.”

“Did Lotta fight as well, then?” Leena wanted to know.

“No, my dear. Women don’t go to war, not a hundred years ago, and not today. But History tells us she followed her husband right to the front.”

“She must have loved him very much then.”

“Unfortunately for her, she did … The soldier Svärd was killed. As you can imagine, after that any young woman would have returned home, but Lotta wasn’t any young woman. So instead she stayed to take care of the wounded, to save lives at the risk of her own.”

Without suspecting that years later she would come to regret it, Leena’s mother had planted the seeds of the anxiety that she felt now, because ever since adolescence Leena had only been waiting until she was eighteen to finally become another Lotta.

“You can never join up!” her father had thundered with the authority of a patriarch at the head of the table. “I won’t allow it!”

“It’s not for you to say,” Leena had defied him, newly impervious 38to his authority. “Today I am an adult. And young men have the right to join the Civic Guard, don’t they?”

“Ah! So that’s it … Young men! So all this fuss is about them, is it?”

“I couldn’t care less about those idiots. I simply want to be useful.”

“But you are that in Finland,” her father exploded. “Here you can do everything! In Europe you wouldn’t have the right to answer back your husband or your father. Even working is frowned on for women, whereas here you can do what you like. If you have strong arms, you can roll your sleeves up and work on a farm or in the fields, carry bricks and sacks of cement on building sites, work in the sugar factory or sawmill. If you have a lively mind you can become a journalist or a politician, or occupy any position in the civil service. Luckily you have both strong arms and a keen mind, but nothing satisfies you.”

“Don’t worry, I’m sure I am going to be one of those. Being Lotta is only for my free time.”

“What if one day our country is at war again, what do you think will happen? You’ll leave with the men. To the frontline!”

“Women don’t go to war, Papa. Not a century ago, and not now.”

“Perkele!” Her father knew when he was beaten. Nothing was more stubborn than a daughter!

*

Now, four years later in October 1939, Leena was 22, the same age as Finland. And following the messenger’s visit to their farm, her parents’ worst fears had become reality.

They would have preferred Leena to be frivolous, uncaring, or even utterly selfish. But they had brought her up so well they had only themselves to blame. Hearts gripped by anguish, they watched as she struggled to close her small suitcase.

When Leena arrived on the station platform as her call-up 39papers required, her grey uniform perfectly ironed, the woman responsible for the Lottas examined her from head to toe.

“Cook? Canteen assistant?”

“Nurse, madam. And I’m also a trained telephone operator.”

“Then you’re in the wrong place.”

She pointed her vaguely towards the far end of the platform. As Leena made her way there, a tall blond beanpole of a man bumped into her and she almost dropped her suitcase.

“So sorry, sweetheart,” the young man apologised, winking broadly at her.

*

The men of Rautjärvi had been taken away. Levied for the nation, like a tax in flesh and blood. The same in every town and village. Next it was the turn of their horses. Sixty-four thousand of them. And the women left behind were already grumbling. The villages had lost their manpower, and since there were now no animals, they knew that for the length of those special manoeuvres they would be the ones pulling the plough, with only the strength of their legs and shoulders to rely on.

A third of all the horses in Finland were requisitioned, led by the halter to cattle wagons of trains whose smoke sometimes covered the entire platform so densely you could not see your closest neighbour.

Gradually, the confident smiles of some of the conscripts helped to ease the general apprehension. An exercise. Nothing more than an exercise, kneeling fathers told their worried children, while the air was filled with the national anthem “Our Country”, whose words everyone had learned since almost before they could speak.

In stations, on roads, throughout Finland, 300,000 men and 100,000 women left their homes that day. In the village of Rautjärvi, they woke up to find there were 372 men and 182 women fewer.

Toivo pushed his way through the crowd on the platform, and 40jumped over the suitcases in his way, forcing apart the kissing couples. Onni struggled to keep up with him.

“Look, over there, I can see Simo!”

He went faster still, almost knocking over a young girl.

“So sorry, sweetheart,” he apologised, winking broadly at her.

*

Half of the cattle trucks had been fitted out. Ranged around a wood stove that needed constant replenishing, long benches were almost comfortable. Everybody found room, the late arrivals pushing their way in. Soon, friendship and the pleasure of being reunited dispelled the uncertainties of their journey.

“You’re wearing your wedding ring?” Toivo said, glancing at Onni’s ring finger.

“Yeah, we didn’t want to wait for the priest. We’ll do it according to the rules when I get back. But at least we’re hitched!”

Pietari soon came to join them, but could find no place to sit. He made do with throwing his kit bag on top of the others, and using them as a mattress.

“Did you hear that, Pietari? Onni gave his future wife a ring just before he left … Doesn’t that remind you of a song?”

An easy question, as the tune was played on the radio almost 20 times a day. And the response came immediately, because you didn’t have to insist much to get a Finnish man to sing. Onni found himself the butt of a musical joke as a wagonload of soldiers burst into song after Pietari had hummed the opening words: “Oh Emma”.6

Oh Emma! Do you remember that night

when the moon was full and we left the ball?

You gave me your heart, vowed to love me

and promised to be mine.41

Believing you, I promised in turn and offered you a ring.

I vowed to be yours

but you broke your promise,

And used my ring

to make a pair of earrings.

Taking it in good heart, Onni himself sang the last couplet; and yet his heart clenched a little when the train began to move.

“We’ll only be gone a week or two,” Pietari reassured him. “She’d have to be really fickle to forget you so quickly.”

10

The railway tracks went no further. The train stopped in open country.

After two days’ travel, the men from Rautjärvi were formed up on the platform amidst a cacophony of contradictory orders. They were 20 kilometres from their camp, and the officers shouted that the distance was to be covered onfoot. To make things worse, the sky had become heavy with the threat of imminent rain. All along the border with Russia, trains were discharging more regiments.

Toivo, Onni, Pietari and Simo had all received the same posting: the 6th Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 34th Regiment of the 12th Division of the IV Army Corps, stationed at Kollaa.

“Kollaa,” Onni grumbled, adjusting his rucksack on his shoulder. “I couldn’t even place it on a map. Does anyone know the region? What’s it like?”

Only a few kilometres from the Russian frontier, the region of Kollaa looked uninviting. Thick forests of silver birch and firs bordered by marshes and lakes surrounded by granite plains that left people exposed to the elements, with only one road wide enough for soldiers or Russian tanks to travel along. More than enough reasons for thinking you would have to be a poor strategist to mount an attack on Finland through here.

*

Lieutenant Colonel Wilhelm Teittinen, commander of the 34th Regiment, had his field tent erected and then summoned his twelve officers. By the dim light of an oil lamp, and with the buzzing43sound of radio tests in the background, Teittinen smoothed a map over a trestle table with the back of his hand.

“Officially,” he announced, “the exercise is a preparation for a possible conflict. Establishing a rear camp around Lake Loimola, creation of a frontline along 30 kilometres of the Kollaa River, digging trenches and anti-artillery shelters, installation of a perimeter of artificial bramble,7 weapons practice, forced marches, and taking up attack and defence positions.”

The officers round the table, all of them career soldiers, had been told weeks earlier that all leave was cancelled: an order which, in military parlance, revealed more than any other an outcome they all feared.

“As long as the negotiations between the Kremlin and Helsinki continue, headquarters is instructing us not to stir up any trouble on the border. Not to show any warlike intent, not to give them the least excuse to feel threatened.”

“Threatened? By us? You could fit 50 Finlands into the Soviet Union.”

Teittinen searched in his uniform jacket, took out a blue Saima packet, and lit a cigarette.

“All the more reason not to antagonise them,” he said. “Let’s stay as unobtrusive as possible. For now, let our soldiers take up their positions, form their companies, put up their tents, stable the horses, collect their things and munitions, and meet their officers.”

“Speaking of officers,” one of the others said in a worried voice, “the quartermaster has found one of them dead drunk, rummaging in the alcohol supplies.”

“You mean Aarne Juutilainen? The legionnaire? He’s wasted no time disgracing himself. What company does he command?”

“The 6th.”

“Poor them,” was the thought shared by all those round the table, as the pounding from thousands of soldiers marching along the muddy ground grew louder and louder.

11

In the general mêlée, the 6th Company’s four platoon commanders, Suuronen, Lehelä, Karlsson and Liimatainen, were searching in vain for their lieutenant, the infamous Aarne Juutilainen. The other units, meanwhile, were regrouping, and the most prepared were pitching their tents in an area where they had felled enough trees to leave them invisible in the midst of one of the region’s thousands of forests.

Three of the four officers were already complaining about being wet nurses.

“Are these exercises any use? It’s not by making them dig foxholes and put up tents that we’ll make combatants of them.”