The World of Peter Rabbit & His Friends: 14 Children's Books with 450+ Original Illustrations by the Author E-Book

Beatrix Potter

1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

In "The World of Peter Rabbit & His Friends," Beatrix Potter presents a delightful anthology of fourteen beloved children's tales, enriched by over 450 original illustrations. The collection encapsulates Potter's signature blend of whimsical storytelling and intricate watercolor depictions, immersing readers in the pastoral charm of the English countryside. Each story features anthropomorphic animal characters, particularly the mischievous Peter Rabbit, and is imbued with moral lessons that resonate with both children and adults. This compilation not only celebrates Potter's literary genius but also serves as a cultural artifact, reflecting the Victorian era's appreciation for nature and the formative principles of childhood exploration and learning. Beatrix Potter (1866-1943) was an English author and illustrator whose intimate relationship with the natural world fueled her literary creativity. Growing up in the secluded Lake District, her early experiences with animals and the countryside deeply influenced her storytelling style and artistic sensibilities. Potter's dedication to conservation and her pioneering spirit as a female author in a male-dominated literary world shaped the charming narratives and vibrant illustrations that have since cemented her status as a celebrated figure in children's literature. I highly recommend this enchanting collection to readers of all ages who wish to revisit the magic of childhood or introduce young ones to classic literature. "The World of Peter Rabbit & His Friends" not only showcases the timelessness of Potter's work but also provides a gateway to appreciating the beauty of nature and the adventures that await within it. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A comprehensive Introduction outlines these selected works' unifying features, themes, or stylistic evolutions. - The Author Biography highlights personal milestones and literary influences that shape the entire body of writing. - A Historical Context section situates the works in their broader era—social currents, cultural trends, and key events that underpin their creation. - A concise Synopsis (Selection) offers an accessible overview of the included texts, helping readers navigate plotlines and main ideas without revealing critical twists. - A unified Analysis examines recurring motifs and stylistic hallmarks across the collection, tying the stories together while spotlighting the different work's strengths. - Reflection questions inspire deeper contemplation of the author's overarching message, inviting readers to draw connections among different texts and relate them to modern contexts. - Lastly, our hand‐picked Memorable Quotes distill pivotal lines and turning points, serving as touchstones for the collection's central themes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

The World of Peter Rabbit & His Friends: 14 Children's Books with 450+ Original Illustrations by the Author

Table of Contents

Introduction

This collection gathers fourteen classic tales written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter, presenting the world of Peter Rabbit and his many companions as a unified imaginative landscape. It offers a carefully framed entry into stories where hedgerows, gardens, farmyards, and cottage interiors set the stage for small but memorable adventures. More than 450 original illustrations by the author accompany the complete texts, preserving the intimate dialogue between image and sentence that defines these works. Together, they invite readers to savor the wit, restraint, and natural observation that have made Potter’s storytelling a cornerstone of children’s literature across generations.

The scope of this volume is single-author and story-centered: a curated set of fourteen picture-book tales that together represent a coherent world rather than a complete works or a collected miscellany. By presenting these stories side by side, the collection emphasizes how recurring places, families, and habits interrelate, allowing patterns of play, peril, and comfort to emerge across titles. Its purpose is both archival and experiential. It gathers authoritative texts with their original illustrations, enabling readers to encounter the tales as they were designed to be read, and to appreciate the cumulative artistry that develops from one story to the next.

The contents here are illustrated children’s stories, sometimes called picture-book tales. They are not novels, plays, poems, essays, letters, or diaries. Each narrative is compact, structured around a sequence of scenes that unfold page by page in concert with the drawings. While they share qualities with animal fables and nursery stories, they resist overt allegory, favoring character, setting, and incident over formal moral pronouncements. The pictures are integral rather than decorative, advancing plot, clarifying setting, and supplying visual humor. The result is a distinct genre blend: concise prose narratives fused with watercolor and ink illustrations, designed for shared reading.

Potter’s stylistic hallmarks are economy, understatement, and quiet precision. Sentences are spare yet musical, with a measured narrative voice that trusts the reader to infer feeling and consequence. Humor arises from timing, choice of detail, and the dignified particularities of each animal’s habits. Anthropomorphism is balanced by naturalist observation: rabbits move like rabbits, ducks like ducks, yet they keep house, wear clothes, and observe society’s small courtesies and lapses. The stories are intimate in scale but expansive in suggestion, pivoting between domestic order and the untidier energies of curiosity, hunger, and play that animate childhood and the countryside alike.

The world of these tales is rooted in the British countryside and its rhythms. Cabbage patches, kitchen gardens, stone walls, lanes, ponds, and woodpiles become miniature theaters of adventure. Interior spaces matter too: parlors, pantries, sewing rooms, laundry rooms, and dollhouses reveal the textures of daily life. Seasons are quietly felt in ripening vegetables, rainy afternoons, and the work that attends them. Tools and materials are named with care, and plants, insects, and small creatures are rendered with keen attention. This close regard for place and habit lends the stories an abiding sense of reality, even at their most fanciful.

Across the collection, certain themes recur. Curiosity tempts a boundary; a gate, a door, or a path beckons; a rule is tested; a consequence follows. Mischief and self-reliance coexist with kindness and help from others. Safety and risk are negotiated through good sense, luck, and the occasional timely intervention. Childhood freedoms meet adult expectations, and the negotiation between them yields both comedy and gentle caution. Rather than preach, the tales invite readers to notice cause and effect, to sympathize with foibles, and to relish the mix of boldness and prudence by which small creatures find their way home again.

Domestic work and craft form another unifying thread: sewing, sweeping, cooking, washing, mending, and gardening are not mere backdrops but sources of drama and satisfaction. Hospitality and etiquette matter, though they are sometimes comically ignored. Clothes and household objects have character, and the vocabulary of making things confers dignity on daily labor. Predators, storms, and accidents appear, yet the prevailing mood favors restoration and resourcefulness. The tales recognize the orderliness of well-kept rooms and rows of vegetables, while honoring the unpredictable energies of the natural world. In this balance, the stories express a humane, enduring vision of ordinary life.

The cast is varied and memorable, with rabbits, mice, hedgehogs, ducks, frogs, cats, rats, foxes, and badgers inhabiting neighboring plots and parlors. Characters sometimes reappear in new contexts, and side figures step forward as protagonists in later tales, creating a sense of continuity without requiring prior knowledge. Family ties, friendships, and neighborly encounters knit the stories together. Each creature is drawn with individuality: a careful housekeeper, an errand-runner, a daydreamer, a keen outdoorsman, a harried parent, a dilettante, a craftsman under pressure. These portraits, at once humorous and respectful, encourage empathy and recognition across ages.

The illustrations are central to the reading experience. Potter’s watercolors and pen work bring tactile specificity to fur, feathers, fabrics, and foliage, while her compositions guide the eye through action and repose. Small vignettes and larger scenes modulate pace, and white space invites contemplation between turns of the page. Expression and gesture are finely judged, allowing pictures to carry nuances the text only hints at. The more than 450 drawings gathered here reveal a consistent unity of tone: delicate, observant, and exacting, yet warmly alive to comedy. Image and narrative together craft suspense, tenderness, and delight with quiet authority.

For readers and listeners, these tales offer an exemplary introduction to narrative form. Clear setups, escalating complications, and satisfying closures are articulated through crisp sentences and thoughtfully placed pictures. The language supports emerging literacy without flattening its music, and the stories reward rereading by yielding fresh details. The tone is companionable rather than didactic; gentle warnings are embedded in events rather than explained. The physical logic of rooms, gardens, and tools makes actions legible, while names and turns of phrase carry a playful charm. In this way, the collection suits shared reading, independent discovery, and intergenerational enjoyment.

The enduring significance of these works lies in their synthesis of art and storytelling, their respect for young readers’ intelligence, and their rootedness in the textures of the natural and domestic worlds. They helped define expectations for the modern picture book, demonstrating how economy, cadence, and visual design can create depth without length. Their influence persists in countless depictions of small creatures with large personalities, yet the originals retain a distinct voice: restrained, affectionate, and keen-eyed. By preserving the author’s text alongside her illustrations, this volume offers not only beloved stories but also a sustained study in narrative craft.

The collection includes The Tale of Peter Rabbit, where a curious rabbit slips into a forbidden garden; The Tale of Benjamin Bunny, which extends that family’s adventures; The Tale of the Flopsy Bunnies, with drowsy rabbits and a tidy garden threat; The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse, a meticulous housekeeper; The Tale of Tom Kitten, a household in upheaval; The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck, a duck seeking a nesting place; The Tale of Samuel Whiskers, also known as The Roly-Poly Pudding, a domestic scrape; The Tailor of Gloucester, a craftsman at a deadline; The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle, a washerwoman hedgehog; The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher, an optimistic angler; The Tale of Pigling Bland, a journey; The Tale of Two Bad Mice, mischief in a doll’s house; The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse, contrasting country and town; and The Tale of Mr. Tod, where fox and badger cross paths.

Author Biography

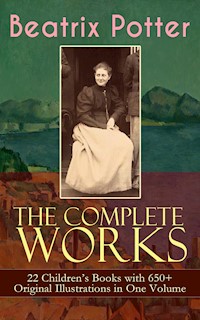

Beatrix Potter (1866–1943) was an English author, illustrator, and natural observer whose small picture books reshaped early twentieth‑century children’s publishing. Best known for The Tale of Peter Rabbit, she paired delicately rendered watercolors with concise prose to evoke rural life and animal character with unusual fidelity. Working across the late Victorian and Edwardian periods into the interwar years, she bridged popular storytelling, natural history, and design. Her career also foreshadowed modern character licensing, and her later commitment to farming and land preservation connected her art to place. Today she stands as a central figure in children’s literature and British conservation history.

Privately educated by governesses rather than in formal schools, Potter developed an early discipline of close looking. She sketched pets, wild animals, and plants, studied specimens under a microscope, and filled notebooks on country holidays in Scotland and the Lake District. Visits to museums and print rooms acquainted her with natural history illustration and the leading picture‑book art of her era. She admired the economy and narrative clarity of illustrators such as Randolph Caldecott, Kate Greenaway, and Walter Crane. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s she kept a detailed journal in a personal code, practicing criticism, observation, and storytelling alongside systematic drawing.

In the early 1890s Potter drafted a story about a mischievous rabbit in an illustrated letter to a child, then reworked and expanded it. After initial rejections, she privately printed a small edition in 1901. The following year Frederick Warne & Co. issued The Tale of Peter Rabbit in color, inaugurating a long partnership. Its success was immediate, aided by the compact format she favored for little hands and the brisk, restrained text. She quickly understood the value of her characters beyond the page and registered a patent for a Peter Rabbit soft toy in the early 1900s, pioneering literary merchandising.

Through the early 1900s she produced a sequence of “little books” that balanced gentle comedy with exact observation. Among the best known are The Tailor of Gloucester, The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, The Tale of Benjamin Bunny, The Tale of Two Bad Mice, The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy‑Winkle, The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher, The Tale of Tom Kitten, and The Tale of Jemima Puddle‑Duck. Their small scale, clear type, and carefully paced images created a distinctive reading rhythm. Critics and readers praised the naturalistic settings, disciplined line, and moral subtlety, and the volumes sold widely, becoming fixtures in nurseries and classrooms.

Alongside fiction, Potter pursued serious amateur study of fungi. She produced hundreds of mycological watercolors and notes, investigating spore germination and the life cycles of mushrooms. In the late 1890s a paper she authored on spore germination was communicated to the Linnean Society of London, though it was not published at the time. Her careful plates, made from direct observation, are valued for their scientific accuracy as well as their artistry, and many are preserved in public collections in the Lake District. This habit of patient, empirical looking informed the textures and behaviors that animate her animal protagonists.

From the 1910s she settled permanently in the Lake District, marrying, managing Hill Top and other farms, and increasingly devoting herself to Herdwick sheep and local land stewardship. Her literary output slowed as she took on practical responsibilities, though she continued to publish, with later works such as The Fairy Caravan and The Tale of Little Pig Robinson. Active in rural affairs, she became a respected breeder and was elected president of a regional sheep breeders’ association shortly before her death, though she did not serve. She worked closely with conservation bodies and acquired properties to secure traditional farming landscapes.

Potter died in the early 1940s, leaving significant landholdings, flocks, and properties that helped shape the modern conservation map of the Lake District. Her books remain continually in print, translated, and adapted, prized for their blend of exact natural detail, quiet humor, and concise narrative design. The farmhouse she once inhabited and her artwork are maintained by the National Trust and related institutions, drawing visitors interested in the link between page and place. Contemporary readers often approach her tales as both charming stories and early environmental visions, in which the habits of animals and the ethics of care are intertwined.

Historical Context

Beatrix Potter’s world took shape across the late Victorian and Edwardian years, when Britain’s industrial cities existed beside an idealized countryside. Born in London in 1866 and publishing for children from 1902 to 1918, she wrote and illustrated within a culture that prized both scientific observation and nostalgic ruralism. The sequence of tales in this collection spans that Edwardian decade and the First World War’s shadow, setting mischievous rabbits, tidy housekeepers, and wary fishermen amid hedgerows, stone cottages, and market towns. This historical frame—high urbanization, expanding literacy, and a flourishing gift-book market—nourished stories that are intimate in scale yet rooted in the broader social and economic rhythms of early twentieth-century Britain.

Potter’s move from metropolitan Kensington to the Lake District after 1905 grounded many scenes in actual farms and lanes. Hill Top, the seventeenth-century house she bought at Near Sawrey with earnings from early successes such as The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), supplied rooms, gardens, and outbuildings recognizable across later tales. The district’s mixed farming—dairying, poultry, pigs, and kitchen plots—provided a matrix for stories of foxes raiding, ducks nesting, and kittens exploring. These narratives draw upon the real textures of Cumbrian life: slate roofs, dry-stone walls, bluebell woods, and steep becks. The rural ideal Potter loved was not static; it was a working landscape shaped by markets, weather, and the vigilance of smallholders.

A disciplined naturalist, Potter trained her eye on fungi, field plants, and small animals long before she was a celebrated author. In the 1890s she produced meticulous mycological drawings, corresponded with specialists, and attempted to present research on spore germination, only to be constrained by gender barriers within learned societies. This practice of specimen-level observation infuses the books. Mice, rabbits, hedgehogs, and ducks are characterized with humor, yet their movement, diets, and habitats are recorded with almost scientific exactness. The stories’ realism—predators hunt, gardens are fenced, weather matters—derives from a culture that valued collecting, sketching, and classifying nature, even as it turned those habits into playful, anthropomorphic scenes for children.

The publishing history is inseparable from the works’ shape and tone. The first Peter Rabbit began as a picture-letter to Noel Moore in 1893, privately printed in 1901, then issued by Frederick Warne & Co. in 1902. Warne worked closely with Potter and editor Norman Warne to standardize a small format at a price accessible to middle-class gift buyers and nursery libraries. The compact scale, legible type, and facing watercolor plates encouraged episodic pacing and page-turn humor. Commercial success funded further tales between 1903 and 1918, knitting together a coherent world in which recurring characters reappear. The partnership also reflects London’s specialized book trade of editors, printers, engravers, and stationers serving a seasonal gift-book economy.

Advances in color reproduction at the turn of the century made Potter’s delicate watercolors economical to print. Half-tone and color plate processes allowed fine gradations in fur, feathers, and textiles without the cost and delay of hand-coloring. This technological context explains the books’ consistent palette and tight integration of text and image. The standardization of small bindings, endpapers, and case colors is equally historical, matching the era’s toy-book and cabinet-size gift traditions. The resulting portable volumes traveled easily through railway bookstalls and circulating libraries, reaching readers in urban parlors and holiday guesthouses. Their production exemplifies how industrial print systems could reproduce intimate, handcrafted aesthetics for broad, transatlantic audiences.

Potter’s career also falls within a period of expanding opportunities for women in cultural professions, even as formal scientific avenues remained constrained. Educated at home by governesses, she cultivated artistic skill and natural history outside university systems. Author-illustrators like Kate Greenaway and Randolph Caldecott had already raised the status of picture books, and Potter negotiated firmly over format, price, and editorial choices. Her ability to earn independent income enabled property purchase in 1905 under a legal environment shaped by nineteenth-century Married Women’s Property Acts. The author’s trajectory—from private maker to public professional—mirrors broader shifts in women’s economic agency and visibility within the Edwardian literary marketplace.

Domestic service, artisanal trades, and cottage industries that sustained towns and villages appear throughout the books because they structured everyday British life. Tailors, laundresses, gardeners, bakers, and gamekeepers were visible, skilled, and often precarious. British households employed servants, and laundry went out to cottage washers; both labor systems inform scenes of tidying, ironing, mending, and sewing. Folk motifs—helpers at night, mischief in dollhouses—interlace with documentary detail about tools, stitches, soap, and starch. The presence of shop windows, haberdashery, and market stalls evokes the small-scale economy of Edwardian high streets, where commissions, credit, and custom orders governed work as much as cash. Craft dignity and fragility animate these narratives.

The treatment of animals reflects two entwined movements: the growth of pet-keeping and animal welfare, and the persistent culture of field sports and pest control. Urban middle classes increasingly kept rabbits, hedgehogs, and other small creatures, while humane societies gained influence. Simultaneously, rural estates protected game birds and killed predators or vermin. Potter’s creatures speak and wear clothes, yet they are bound by ecological and social roles. Foxes raid poultry, rats gnaw, cats hunt, and frogs fish from lily leaves. This balance—tenderness toward individual animals, frankness about predation—matches period sensibilities that sentimentalized nature while accepting a working countryside’s harshness and hierarchies.

Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century British agriculture left clear fingerprints on the stories’ settings and plot devices. Kitchen gardens and walled plots mark a world of seasonal abundance guarded by fences, scarecrows, and gardeners’ rights. Regulations on animal movement, established to curb disease, inform details like pig licenses and journeys to market. Smallholders bartered eggs, butter, and pork, while itinerant dealers and carriers stitched together rural supply chains. Weather, gleaning, and gleaners’ baskets recur in imagery because harvest rhythms defined family economies. The geography—lanes, stiles, copses—captures the legal and cultural shapes of common paths and hedged fields that had governed English rural life since enclosure.

Consumer culture, imported toys, and the international trade in miniatures underpin scenes of dollhouses and indoor mischief. By the 1900s, middle-class nurseries were furnished with German-made dolls, clockwork furnishings, and tiny crockery, all sold through London shops and seaside resorts. The stories’ exact renderings of parquet floors, gilt chairs, and porcelain reveal a designer’s eye for material culture and the fragility of display. Potter also innovated in character merchandising, registering a soft toy design for Peter Rabbit in 1903 and developing board games and figurines. These commercial experiments aligned with new copyright protections and demonstrated how a children’s book world could extend into tangible playthings.

Specific British places anchor multiple tales and mark the era’s mobility. A Christmas visit to Gloucester in the late 1890s supplied streets and shopfronts for an eighteenth-century-set narrative about a tailor and a commissioned garment. The Lake District’s Derwentwater and the boggy margins of its streams gave amphibian adventures their watery stage. Near Sawrey’s orchards, porches, and pigsties recur because Potter drew them from life at Hill Top after 1905. Meanwhile, the growth of railway travel and postal networks connected London readers to provincial scenes and enabled the author to work between city and country. Urban and rural codes collide fruitfully throughout the oeuvre.

Public health reforms, sanitation campaigns, and municipal modernization help explain the menacing presence of rats and the vigilance against vermin. The late Victorian city struggled with refuse, sewers, and food safety; rat-catching became a recognized trade and a popular spectacle, even as municipalities professionalized control. In the countryside, rats imperiled stored grain, eggs, and chicks. When whiskered antagonists appear in kitchens and pantries, they echo period anxieties about contamination and loss. The books magnify domestic thresholds—skirting boards, floorboards, drains—where cleanliness and disorder contend. Threats are real, but the tone remains balanced by humor, community resourcefulness, and the reassuring return of order after upheaval.

The author’s personal timeline intersects with shifts in mood across the series. The triumph of Peter Rabbit in 1902 was followed by intense production through the decade, then a more selective pace. Norman Warne’s death in 1905 was a private blow during a year of professional consolidation and the purchase of Hill Top. Potter married the Hawkshead solicitor William Heelis in 1913, deepening her commitment to farming. The First World War (1914–1918) altered markets, supplies, and readers’ horizons, and later stories absorb a quieter, sometimes sterner perspective on risk, travel, and safety. Across these years, continuity rests in careful drawing, rural detail, and tightly constructed plots.

Arts and Crafts ideals of workmanship infuse depictions of sewing, knitting, and household order. The movement’s respect for hand labor and vernacular design was in the air, shaping taste for simple forms, natural materials, and honest craft. In scenes of tailoring, cutting, pressing, and hemming, tools and techniques are named with precision, and fabrics are shown with weaves and nap. Domestic interiors feature earthenware, copper, scrubbed tables, and plain textiles—the dignity of utility. Clothing and uniforms follow contemporary fashion’s silhouettes and trimmings, registering the Edwardian eye for detail. Children encountered not abstract morals but a material ethics of care, repair, and well-kept things.

The Edwardian book trade’s structures enabled the series’ reach. The Net Book Agreement stabilized prices, railway bookstalls broadened distribution, and gift seasons—Christmas and Easter—organized sales. Warne’s catalog positioned compact, affordable picture books alongside classics and series fiction, while American and colonial markets received simultaneous or near-simultaneous issues. Advertising relied on catalogues, window displays, and word of mouth. The small format encouraged impulse purchases and repeat collecting, and steady reprints kept earlier titles continuously available as new ones appeared. In this ecosystem, the characters’ intertextual appearances built brand recognition long before modern franchising vocabulary existed, ensuring a coherent world across many volumes.

Conservation, land stewardship, and local institutions anchor the author’s later life and retrospectively frame the tales’ respect for hedgerows and farms. The National Trust, founded in 1895 with Lake District advocate Hardwicke Rawnsley as a key figure, articulated a vision for protecting landscapes and traditional husbandry. Potter became a working farmer and respected Herdwick sheep breeder, acquiring adjacent farms and ultimately bequeathing extensive property to the Trust in 1943. The books’ attention to native breeds, boundary walls, and rotational use mirrors a philosophy that sees storytelling and stewardship as allied tasks: to observe closely, to keep what is sound, and to pass it on intact.

Taken together, the works form a cultural document of modern Britain negotiating change. Published between 1902 and 1918, they compress scientific curiosity, publishing innovation, women’s professional agency, and rural crafts into brisk narratives populated by familiar animals. Named places—Gloucester, the Lakes, cottage kitchens—anchor a durable map where characters cross paths from one tale to another. The humor is domestic, the perils credible, the morals understated. That balance explains their long afterlife across reprints and translations. Their historical context—industrial cities, improved trains, new color presses, conservation ideals—remains embedded in every garden wall, tailor’s bench, and riverside reed that frames the adventures of Potter’s creatures.

Synopsis (Selection)

The Tale of Peter Rabbit

A curious young rabbit sneaks into Mr. McGregor's garden against his mother's warning and is nearly caught in a series of close calls.

The Tale of Benjamin Bunny

Peter and his cousin Benjamin return to Mr. McGregor's garden to retrieve Peter's lost clothes and run into peril when a lurking cat upends their plan.

The Tale of the Flopsy Bunnies

The Flopsy Bunnies fall asleep in Mr. McGregor's lettuce patch and are discovered. Their parents must devise a clever rescue.

The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse

A tidy woodland mouse struggles to keep her house clean while a stream of intrusive guests track in dirt and demand food. She methodically reclaims her space.

The Tale of Tom Kitten

Tom Kitten and his sisters are dressed for a formal visit, but outdoor mischief ruins their fine clothes. A meddlesome flock of ducks turns the preparations into a comic muddle.

The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck

Eager to hatch her own eggs, Jemima leaves the farm seeking a quiet nest and falls under the sway of a smooth-talking fox. Farmyard allies must counter the danger.

The Tale of Samuel Whiskers (The Roly-Poly Pudding)

Tom Kitten wanders into the attic and is captured by two rats, Samuel Whiskers and Anna Maria, who scheme to cook him into a roly-poly pudding. A frantic search follows through the walls and rafters.

The Tailor of Gloucester

A poor tailor, ill and short of thread, faces an urgent commission to sew the mayor's wedding coat. Unexpected helpers work through the night while a sulky cat complicates matters.

The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle

Little Lucie searches for missing clothes and meets Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle, a hedgehog laundress who has been washing items for the neighbors. The visit blends everyday chores with a touch of woodland magic.

The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher

Mr. Jeremy Fisher, a frog, sets out on a fishing trip to host a dinner for friends, but mishaps with weather and predators turn the outing into a near-disaster.

The Tale of Pigling Bland

Sent to market with his brother, Pigling Bland is separated and must navigate a series of scrapes on the road. He meets another pig and considers an escape from an overbearing farmer.

The Tale of Two Bad Mice

Two curious mice break into a doll's house, discover the pretend food is inedible, and wreak havoc in frustration. Their mischief leads to comic destruction and later attempts to make amends.

The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse

After a vegetable hamper mix-up, country mouse Timmy Willie experiences the bustle and hazards of a city household. Later, Johnny Town-Mouse visits the countryside, and both weigh the comforts of home.

The Tale of Mr. Tod

When Tommy Brock kidnaps Benjamin Bunny's children, Benjamin and Peter track him to the house of the fox, Mr. Tod. A tense standoff between rival predators endangers everyone as the rescuers look for a chance to act.

The World of Peter Rabbit & His Friends: 14 Children's Books with 450+ Original Illustrations by the Author

The Tale of Peter Rabbit

ONCE upon a time there were four little Rabbits, and their names were—Flopsy, Mopsy, Cotton-tail, and Peter.

They lived with their Mother in a sand-bank, underneath the root of a very big fir-tree.

'Now, my dears,' said old Mrs. Rabbit one morning, 'you may go into the fields or down the lane, but don't go into Mr. McGregor's garden: your Father had an accident there; he was put in a pie by Mrs. McGregor.'

'Now run along, and don't get into mischief. I am going out.'

Then old Mrs. Rabbit took a basket and her umbrella, and went through the wood to the baker's. She bought a loaf of brown bread and five currant buns.

Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cotton-tail, who were good little bunnies, went down the lane to gather blackberries:

But Peter, who was very naughty, ran straight away to Mr. McGregor's garden and squeezed under the gate!

First he ate some lettuces and some Stringbeans; and then he ate some radishes;

And then, feeling rather sick, he went to look for some parsley.

But round the end of a cucumber frame, whom should he meet but Mr. McGregor!

Mr. McGregor was on his hands and knees planting out young cabbages, but he jumped up and ran after Peter, waving a rake and calling out, 'Stop thief!'

Peter was most dreadfully frightened; he rushed all over the garden, for he had forgotten the way back to the gate.

He lost one of his shoes amongst the cabbages, and the other shoe amongst the potatoes.

After losing them, he ran on four legs and went faster, so that I think he might have got away altogether if he had not unfortunately run into a gooseberry net, and got caught by the large buttons on his jacket. It was a blue jacket with brass buttons, quite new.

Peter gave himself up for lost, and shed big tears; but his sobs were overheard by some friendly sparrows, who flew to him in great excitement, and implored him to exert himself.

Mr. McGregor came up with a sieve, which he intended to pop upon the top of Peter; but Peter wriggled out just in time, leaving his jacket behind him.

And rushed into the tool-shed, and jumped into a watering can. It would have been a beautiful thing to hide in, if it had not had so much water in it.

Mr. McGregor was quite sure that Peter was somewhere in the tool-shed, perhaps hidden underneath a flower-pot. He began to turn them over carefully, looking under each.

Presently Peter sneezed—'Kertyschoo!' Mr. McGregor was after him in no time.

And tried to put his foot upon Peter, who jumped out of a window, upsetting three plants. The window was too small for Mr. McGregor, and he was tired of running after Peter. He went back to his work.

Peter sat down to rest; he was out of breath and trembling with fright, and he had not the least idea which way to go. Also he was very damp with sitting in that can.

After a time he began to wander about, going lippity—lippity—not very fast, and looking all around.

He found a door in a wall; but it was locked, and there was no room for a fat little rabbit to squeeze underneath.

An old mouse was running in and out over the stone doorstep, carrying peas and beans to her family in the wood. Peter asked her the way to the gate, but she had such a large pea in her mouth that she could not answer. She only shook her head at him. Peter began to cry.

Then he tried to find his way straight across the garden, but he became more and more puzzled. Presently, he came to a pond where Mr. McGregor filled his water-cans. A white cat was staring at some gold-fish, she sat very, very still, but now and then the tip of her tail twitched as if it were alive. Peter thought it best to go away without speaking to her; he had heard about cats from his cousin, little Benjamin Bunny.

He went back towards the tool-shed, but suddenly, quite close to him, he heard the noise of a hoe—scr-r-ritch, scratch, scratch, scritch. Peter scuttered underneath the bushes. But presently, as nothing happened, he came out, and climbed upon a wheelbarrow and peeped over. The first thing he saw was Mr. McGregor hoeing onions. His back was turned towards Peter, and beyond him was the gate!

Peter got down very quietly off the wheelbarrow, and started running as fast as he could go, along a straight walk behind some black-currant bushes.

Mr. McGregor caught sight of him at the corner, but Peter did not care. He slipped underneath the gate, and was safe at last in the wood outside the garden.

Mr. McGregor hung up the little jacket and the shoes for a scare-crow to frighten the blackbirds.

Peter never stopped running or looked behind him till he got home to the big fir-tree.

He was so tired that he flopped down upon the nice soft sand on the floor of the rabbit-hole and shut his eyes. His mother was busy cooking; she wondered what he had done with his clothes. It was the second little jacket and pair of shoes that Peter had lost in a fortnight!

I am sorry to say that Peter was not very well during the evening.

His mother put him to bed, and made some camomile tea, and she gave a dose of it to Peter!

'One table-spoonful to be taken at bed-time.'