Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

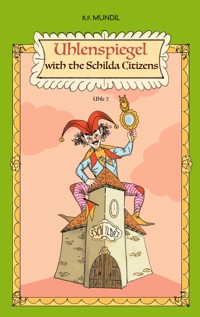

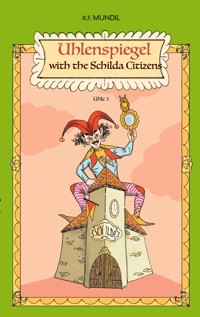

Uhlenspiegel is a prankster who lived in Germany in the Middle Ages, played tricks on people by often taking idioms literally, knowing how to take advantage of them and mocking his fellow citizens. The Schilda citizens are inhabitants of the fictional town of Schilda, who were known for their naive actions. One of the most famous stories is that they forgot the windows when building the town hall and therefore tried to bring in the light with buckets. In this book, the prankster Uhlenspiegel meets the foolish Schilda citizens. The strange encounters that ensue are told in this book in the form of short stories.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 60

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For

Corvin

who is working admirably

towards his dream

Index

1. Golden air

2. Double life

3. The locked open town

4. Profound(ly abysmal)

5. Deep insights

6. Clairvoyance in the darkness

7. Flying gifts

Introduction

On sense and nonsense or on the sense of senselessness or on the sense of nonsense.

One foolishness is not good, two foolishnesses are not necessarily better, unless they try to out(trump) each other negatively or, to put it another way, they try to compensate for each other, a kind of upside-down complete compensation deal in such a way that both decompensate in the sense of not becoming even worse but disappearing together in unison.

Whether that makes sense remains to be seen. But sense is one of those things. Even in nonsense there is at least (linguistically) sense, to a certain extent the sense of not making sense, not andsense but nonsense.

Why has language never invented the word andsense? Hard to explain! Because in a common, pardon, hardly general way there are sometimes two senses in one thing. We are quite content to find one sense in a thing; at most, by using all our senses, it may be possible to elicit several senses from a thing, the sense of touch to be felt, the sense of hearing to be heard, a sense of feeling that cannot be grasped, and so on.

But all this seems senseless (or senseLess, perhaps Sense(less)).

SenseLess, the sense is perhaps a lot as in a draw, sometimes to be found in a thing, often not, just like a lot. (Translator's note: this is a play on the German word 'los' which means 'less' and 'lot in a draw' but it can't be translated directly into English).

Sense-less. That makes more sense. Someone has unhooked the sense of a thing, like you unhook a moored boat, and both sense and boat are soon gone. A boating sense, if that makes any sense. Still there but gone, just no longer there, pardon no longer here but (somewhere) still there.

So if something is sense less, pardon, senseless, that is, without sense, how can it make double sense? A nothing can hardly be doubled, something that is senseless can hardly be doubly senseless, more senseless. Senseless can only mean that the sense is no longer so solid, will soon disappear, be completely gone and haste is required to grasp it before it is even more loose, completely loose, that is, completely gone.

Senseless, that is, something without sense and in a double sense. Does that make (at least one(1)) sense? To make one out of nothing would be a magic trick, to make one out of a double sense would be an inestimable loss. A sense of loss, pardon a loss of sense.

This digression made little sense, perhaps even no sense at all.

Senseless, double sense? That makes no sense at all. Why would it make sense to look twice at something that doesn't even exist?

An empty plate doesn't get any fuller if we look at it twice. And it is absolutely senseless or absurd or even nonsensical to look twice at something that is not there. At some point, we (or our senses) will think that we have been deceived, that we (via the sometimes senseless path of our senses) have tricked ourselves, so to speak.

In a figurative sense, there is something of these thoughts in the following stories.

Two main protagonists ‒ the lone fighter Uhlenspiegel, but with the army of his mischievous thoughts ‒ meets the armies of the numerous Schilda citizens (rather less or let's say more neutrally armed with other thoughts).

Is such an encounter sensible? Is it perhaps senseless? Or does it perhaps make at least double sense, an and-sense, if not multiple sense?

All this remains open, just as we should go through life with open senses in order to recognize what makes sense or even to discover a hidden sense in an adventurous way - to find out where there is a (the) sense or whether it is simply missing, a kind of non-sense and in this sense as non-sense even less than nonsense, which exists somewhere, otherwise it would not be nonsense.

To summarize or to sum up the sense: everyone has to find out for themselves whether it makes sense to read these stories or to bring Uhlenspiegel together with a village of Schilda citizens. That in turn would then make sense. In this way, every reader would make sense of these stories (pardon interpret sense into them) where there was no sense before and it would have made sense (for everyone) to write or read these stories.

However, they should approach the sense and nonsense of these stories unencumbered (meaning already encumbered with sense but equipped with unencumbered senses).

With this in mind: lots of sense enjoyment.

*PS.1: Topical note

Perhaps this explains the phenomenon of dictatorships that is emerging again today. A single person (but with almost absolutely immovable sense) is confronted with a huge mass of people whose senses are rather dulled. A constellation that not only makes no sense, but makes (pardon contains) an incredibly dangerous sense. More than nonsense, much more, the strongest nonsense there can ever be.

PS.2: Reading recommendation

It may make sense to read only one story a month, or it may not make sense to read more than one story a month. That's why this book contains twelve stories. If you feel like reading more, you can of course read all twelve stories in one day instead of just one story a month.

You will want to get to the stories at last. Here you go. Have fun.

1.

Golden air

As Uhlenspiegel sat in front of his hut, the warm summer wind blowing around his nose, it came to his mind, as if carried by the wind, to seek out the citizens of Schilda. Important ideas had been rushing through his brain and the time had come to give the people of Schilda their rightful share of these ideas.

He took three empty sacks, stretched them open so that they looked like fish mouths and took one last nap before setting off the next day.

A day later, he had reached the place he had come to love. The news of his arrival spread like wildfire, but it was more like a scare story. All too vividly present in the minds of the citizens of Schilda was what they had to thank him for in the truest sense of the word.

Everyone fled into their homes, barricaded windows and doors and hoped that the strange fellow would disappear again before he arrived.

That was not the case. However, their curiosity did not allow them to hold out for long, because Uhlenspiegel was standing in the middle of the market square, in front of him the three large sacks he had brought with him, from which he took something out from time to time. Each time, his arm seemed to vibrate like a trembling rattlesnake after he pulled it out of the sack.