Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

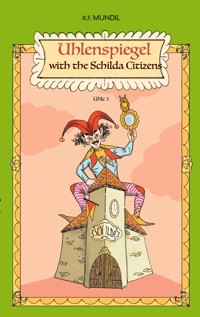

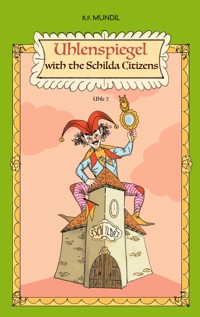

Uhlenspiegel is a prankster who lived in Germany in the Middle Ages, played tricks on people by often taking idioms literally, knowing how to take advantage of them and mocking his fellow citizens. The Schilda citizens are inhabitants of the fictional town of Schilda, who were known for their naive actions. One of the most famous stories is that they forgot the windows when building the town hall and therefore tried to bring in the light with buckets. In this book, the prankster Uhlenspiegel meets the foolish Schilda citizens. The strange encounters that ensue are told in this book in the form of short stories.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 91

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Samuel Friedrich

Index

Dangerous dream of gold

Nothing (–) makes you happy

Money stinks (doesn’t stink)

White/wise portable stoves

Fairytale everyday life

Dry run

The black smouldering rose

House-stacked time

A strange unfortunate chain of events

Make one from two (by yourself)

Sweet post-Christmas decree

Death without end

Introduction

On sense and nonsense or on the sense of senselessness or on the sense of nonsense.

One foolishness is not good, two foolishnesses are not necessarily better, unless they try to out(trump) each other negatively or, to put it another way, they try to compensate for each other, a kind of upside-down complete compensation deal in such a way that both decompensate in the sense of not becoming even worse but disappearing together in unison.

Whether that makes sense remains to be seen. But sense is one of those things. Even in nonsense there is at least (linguistically) sense, to a certain extent the sense of not making sense, not andsense but nonsense.

Why has language never invented the word andsense? Hard to explain! Because in a common, pardon, hardly general way there are sometimes two senses in one thing. We are quite content to find one sense in a thing; at most, by using all our senses, it may be possible to elicit several senses from a thing, the sense of touch to be felt, the sense of hearing to be heard, a sense of feeling that cannot be grasped, and so on.

But all this seems senseless (or senseLess, perhaps Sense(less)).

SenseLess, the sense is perhaps a lot as in a draw, sometimes to be found in a thing, often not, just like a lot. (Translator's note: this is a play on the German word 'los' which means 'less' and 'lot in a draw' but it can't be translated directly into English).

Sense-less. That makes more sense. Someone has unhooked the sense of a thing, like you unhook a moored boat, and both sense and boat are soon gone. A boating sense, if that makes any sense. Still there but gone, just no longer there, pardon no longer here but (somewhere) still there.

So if something is sense less, pardon, senseless, that is, without sense, how can it make double sense? A nothing can hardly be doubled, something that is senseless can hardly be doubly senseless, more senseless. Senseless can only mean that the sense is no longer so solid, will soon disappear, be completely gone and haste is required to grasp it before it is even more loose, completely loose, that is, completely gone.

Senseless, that is, something without sense and in a double sense. Does that make (at least one(1)) sense? To make one out of nothing would be a magic trick, to make one out of a double sense would be an inestimable loss. A sense of loss, pardon a loss of sense.

This digression made little sense, perhaps even no sense at all.

Senseless, double sense? That makes no sense at all. Why would it make sense to look twice at something that doesn't even exist?

An empty plate doesn't get any fuller if we look at it twice. And it is absolutely senseless or absurd or even nonsensical to look twice at something that is not there. At some point, we (or our senses) will think that we have been deceived, that we (via the sometimes senseless path of our senses) have tricked ourselves, so to speak.

In a figurative sense, there is something of these thoughts in the following stories.

Two main protagonists ‒ the lone fighter Uhlenspiegel, but with the army of his mischievous thoughts ‒ meets the armies of the numerous Schilda citizens (rather less or let's say more neutrally armed with other thoughts).

Is such an encounter sensible? Is it perhaps senseless? Or does it perhaps make at least double sense, an and-sense, if not multiple sense?

All this remains open, just as we should go through life with open senses in order to recognize what makes sense or even to discover a hidden sense in an adventurous way - to find out where there is a (the) sense or whether it is simply missing, a kind of non-sense and in this sense as non-sense even less than nonsense, which exists somewhere, otherwise it would not be nonsense.

To summarize or to sum up the sense: everyone has to find out for themselves whether it makes sense to read these stories or to bring Uhlenspiegel together with a village of Schilda citizens. That in turn would then make sense. In this way, every reader would make sense of these stories (pardon interpret sense into them) where there was no sense before and it would have made sense (for everyone) to write or read these stories.

However, they should approach the sense and nonsense of these stories unencumbered (meaning already encumbered with sense but equipped with unencumbered senses).

With this in mind: lots of sense enjoyment.

*PS.1: Topical note

Perhaps this explains the phenomenon of dictatorships that is emerging again today. A single person (but with almost absolutely immovable sense) is confronted with a huge mass of people whose senses are rather dulled. A constellation that not only makes no sense, but makes (pardon contains) an incredibly dangerous sense. More than nonsense, much more, the strongest nonsense there can ever be.

PS.2: Reading recommendation

It may make sense to read only one story a month, or it may not make sense to read more than one story a month. That's why this book contains twelve stories. If you feel like reading more, you can of course read all twelve stories in one day instead of just one story a month.

You will want to get to the stories at last. Here you go. Have fun.

1.Dangerous dream of gold

As fate would have it, Uhlenspiegel was burdened with a serious illness. When he finally recovered after many weeks, he realized that not only the illness was gone, but also all the money he had worked so hard to obtain by trickery. Now the illness had had something to do with his stomach, and as Uhlenspiegel understood so much about medicine, a stomach has no hands and feet, it could not possibly have been the illness itself that had carried the money away. The only remaining cause of the disappearance was the quack doctor who had treated Uhlenspiegel and had been paid a princely sum for it.

If I have gone through stomach disease myself, I now know how to cure it, Uhlenspiegel thought. No other profession − he was thinking of the quacks − seemed more suitable for him to regain possession of a small fortune and, on top of that, it didn't seem to matter to him how an illness was treated, it lasted just as long with medicine as without, only illnesses put people in strange states in which they wanted to be treated with martial methods and stuffed with bitter medicine like a goose.

The first thing Uhlenspiegel did was to write himself a few decent references regarding his reputation. He invented all sorts of strange names, of emperors who lived in China, Arabia and elsewhere and attested to him in strange characters that he had repeatedly snatched them from the clutches of a deadly disease. They also deeply regretted that he intended to return to his homeland and was therefore unable to remain their imperial physician any longer.

Nevertheless, they offered him the opportunity to return at any time and take up his old position, even if he was old, blind and deaf, for even in such a state there could be no better physician in the whole world than him.

Thus, equipped and clad in suitable clothing, Uhlenspiegel set off for Schilda. Fate meant well with him, or perhaps fate had a guilty conscience because of the serious illness it had saddled him with.

On the market square, Uhlenspiegel saw a man sitting and begging who seemed strange to him. Both his legs and his arms were wrapped in white bandages, and he just had his fingers free to hold a hat for collecting coins. Every now and then a citizen of Schilda would stop and throw a little money into the hat.

Uhlenspiegel positioned himself in front of the poor devil and shouted so that he could be heard all over the marketplace, asking if he wanted him, a well-traveled and experienced doctor, to help him.

The beggar nodded: Of course, he would like nothing better than to be able to stand on his own two feet again and work with his own hands instead of sitting day in, day out as a miserable creature in the marketplace, dependent on the alms of others.

Uhlenspiegel, however, thought he saw through him, that it was nothing more than that he had made himself comfortable, earning his money in a pleasant spot in the sun and in a comfortable seat, on top of having his food brought to him and being carried back and forth in the morning and evening like an emperor in a sedan chair. In the meantime, a good crowd of onlookers had gathered, just as Uhlenspiegel had intended.

He raised his hands imploringly over the sick man, mumbled a few unintelligible words, reached into his pocket and told the man to take the medicine. In a moment, however, he would recover and be able to walk on his own feet again, which is what every human being is given to do.

The beggar swallowed the medicine and everyone stared at him with wide, staring eyes. Everyone had their ailments, if the poor devil actually jumped up it should be easy for the strange doctor to cure them of their far more significant ailments, even if they seemed far less serious on the outside.

Nothing happened. On the contrary. The patient seemed to be worse off than before.

Now Uhlenspiegel was beginning to get upset, as he thought he had an actor in front of him who was ruining his good business with money. He approached the beggar, leaned forward, said something about fair payment, grabbed the money-filled hat and ran off. You should have seen the beggar. He jumped up like the devil and rushed after him, his arms and legs still wrapped in white bandages, to get his money back.

When Uhlenspiegel saw this, he stopped. The beggar also stopped, only now realizing what had happened. Uhlenspiegel, however, took advantage of the moment and explained unctuously that it was easy for him to get a paralytic on his feet, as everyone had seen with their own eyes, and that he would be ready tomorrow to free everyone from their complaints.