14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

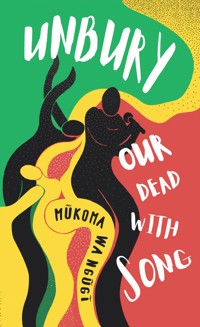

- Herausgeber: CASSAVA REPUBLIC

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A love letter to music, beauty, and imagination. In the seedy ABC boxing club in Nairobi, four musicians—The Diva, The Corporal, the Taliban Man, and Miriam—gather for a competition to see who can perform the best Tizita. Listening from the audience is Kenyan tabloid journalist John Thandi Manfredi, whose own life makes him vulnerable to the Tizita. Desperate to learn more, he follows the musicians back to Ethiopia, hoping to learn the secret to the music from their personal lives and histories. His search takes him from the idyllic Ethiopian countryside to juke joints and raucous parties in Addis Ababa where he quickly learns that there is more to these performers than meets the eye. From the humble home life behind the Diva's glamorous facade, to the troubling question of the Corporal's military service history, Manfredi discovers that the many layers to this musical genre are reflected in the lives and secrets of its performers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

UNBURY OUR DEAD WITH SONG

Mũkoma Wa Ngũgĩ

Dedicated to Bezawork Asfaw, Mahmoud Ahmed, Aster Aweke and other singers of the Tizita.

When Tizita comes down on me, I become a stranger to my life And I become a vagabond and a wanderer. —Mahmoud Ahmed

One day, I will be dead and gone my grave untended date of birth and death on my gravestone from centuries past and only my Tizita will remain. —John Thandi Manfredi

Contents

1

‘To be crowned the winner was like being named the singer of Ethiopia’s soul.’

At the Ali Boxing Club (or the ABC, as we regulars called it), a metallic steel guitar, a kora, a nyatiti, a krar, an accordion, a regally carved antic begena and a masenko were laid out, like weapons on display, on polished three-legged ivory stools in the boxing ring-cum-music stage. There was even a dignified piano, with its black hind legs peering through an expensive-looking gold cloth, at the far-left corner of the ring. In the middle of the ring there were two 1950s silver announcer microphones, lowered from the ceiling to a chair lit by dancing, coloured stage lights. The instruments on stage formed an island, standing tall against the pandemonium of gamblers and bookies in various stages of excited drunkenness, an ocean-crowd of happiness seekers that every now and then ebbed and crashed against its shores.

Located in the middle of a nowhere that was only five or so kilometres from the city centre, the ABC was a black hole that swallowed us up, destroying our insides with expensive but cheaply priced beer and whisky, only to spit us out in the early hours of the morning. The money to be made was in the gambling, the cheap booze a lubricant between us and our money. It attracted a mixture of been-tos and those for whom Kenya was the land of their exile; sheng-speaking Kenyan bohemian types in permanent transition to adulthood; those from the middle class trying to climb their way up; the affluent and their expatriate friends who came down to slum and burn through money.

Something ‘serious,’ as we Kenyans like to say, was about to unfold. Tonight, for the first time, Ethiopian musicians were here — they were going to compete, singing the Tizita. The Tizita was not just a popular traditional Ethiopian song; it was a song that was life itself. It had been sung for generations, through wars, marriages, deaths, divorces and childbirths. For musicians and listeners exiled in Kenya, the US and Europe, or trying to claim a home in Israel as Ethiopian Jews, the Tizita was like a national anthem to the soul, for better and worse. As I got to learn more about the Tizita, I would understand why this competition mattered to the musicians — to be crowned the winner was like being named the singer of Ethiopia’s soul.

Every musician, no matter how talented or popular, had to sing the song at least once in their career in order to be respected. It marked the difference between, say, a Madonna and a Billie Holiday. Or, even more contentiously, the difference between a Michael Jackson and a Sam Cooke. Yes, Michael was the best entertainer to ever live, but put next to Sam Cooke, something was wanting, that extra.

There was a caveat though; a badly done Tizita could destroy a career. Indeed, many flourishing careers in Ethiopian pop music had withered away after an ill-fated attempt at singing the Tizita. A musician comes along and releases a pop song that does well. He or she feels they have now graduated to singing the Tizita. But not quite. Managers and producers issue warnings, but the pop musician, adored by millions of fans, disregards their advice…. There is no coming back from a bad Tizita.

The ABC was my favourite spot — you could say I was slumming the slummers — as it was from that perverse energy that I created stories for The National Inquisitor, a Nairobi-based tabloid owned by a major British corporation. At the Inquisitor, we did not run stories about celebs living in sterilised bubbles or politicians taken over by aliens; we were not your typical Western tabloid. At the very core of a story, we worked with the truth — scandalous and salacious, but the truth, nevertheless.

Say you are the politician who uses public funds to buy diamond-studded sex toys. In real life, I probably saw one dildo and perhaps gold-plated handcuffs, but in print this becomes ten diamond-studded dildos kept in a sex dungeon. We had never been sued — in a court of law and in the court of public opinion. Would it matter just how many sex toys you bought with public funds? And if you are a Catholic priest using church money to build mansions and I tabloid your story, what little boys, now grown men, will crawl out of your cloak as the court case drags on? That grain of truth inside our stories was enough to keep the politicians, the celebs and the priests out of our way.

But really, if my friends at the ABC were to tell you my story, they would say I am the guy who accompanies the guy with the money and the beautiful woman. The foil guy, the guy in the middle of the crowd telling jokes, beers thrust into his hands; the guy who gets wet kisses from women who go home with other men. The best man at weddings and eulogiser at funerals. That my world was an open universe where people could saunter in and out as they pleased — and I welcomed them as a surrogate, temporary family. I did not mind; that is how I got my stories, being close to the action without being at the centre. So The National Inquisitor kept me close to the beautiful, wounded and violent heart of the ABC, and of Nairobi.

If you must think of me as I bring you this story about a Tizita competition in an illegal boxing club in Nairobi, picture me with a near-empty beer bottle in hand going up to the bar where I will find Miriam the bartender, and Miriam, without asking, will place two Tuskers in front of me. Picture me, a nondescript guy, two pens comically sticking out of my short but carefully combed afro, following old, dried and fresh blood spots to the front row seats to listen to some Tizita.

See me sipping my Tusker beer, waiting for some story or, on this night, for the story of the Tizita to unfold. Imagine a familiar feeling of suddenly being unbalanced coming back to me and my wanting to go on until I tipped on one side or the other — of something I do not know yet.

And then, much later, see me leave. I am going over to my apartment where I might or might not find Alison, my British editor at the Inquisitor, in bed.

2

‘It is like asking who has a better heart, a better soul — how do you measure that?’

Miriam liked to claim she was 90 years old, but I suspected 70 or thereabouts — when you age too fast, there is some residue of lost youth that remains underneath each wrinkle. I had done a generous story about her called “The Oldest Bartender in Kenya,” and for that she always gave me a few drinks for free. First she had lost her mother to the politically-induced famine — the dictator, Haile Mengistu, had used starvation as a weapon against civilians to punish the rebels. Then, before they could have children, she had lost her husband to the armed struggle to oust Mengistu. That was when Ethiopian anti-Mengistu and Eritrean nationalists wanting to liberate Eritrea from Ethiopia fought their common enemy together, an enemy whose allegiances to the West and the Russians shifted with his fortunes. Then she lost her sister to the fratricidal war that ensued between the Ethiopians and Eritreans after they ousted Mengistu. Eventually, she was left standing alone. So she made her way to Kenya, in ‘the worst kind of loneliness, of being lonely and the last one standing,’ as she had described it. She had run into Mr. Selassie, and from their mutual despair, the ABC was born.

‘Hey, babe, how did they decide on the musicians?’ I asked her as she brought me my two pilsners.

‘Nobody tells this old fool anything — it’s serve beer and shut up over here,’ she answered, opening one.

I laughed and made as if to walk away.

‘That doesn’t mean I haven’t heard things though — no wonder you are such a poor reporter,’ she said, shaking her head side to side. ‘You know the Tizita?’

‘A little bit — it’s a long story, but I know the Tizita from Boston; there’s a large Ethiopian community there, pan-Africanism, partying….’ I answered.

‘The musicians tonight, they are the best of the best,’ she said, pointing at Mr. Selassie. ‘He selected them.’

I started to laugh.

It was difficult to reconcile the ABC, and even more so Mr. Selassie, with what amounted to a sad, bluesy Ethiopian song. Never before had I met a man who so perfectly fit a stereotype of who he was — so much so that he begged the chicken and egg question of who or what came first. He was a short, balding man with what remained of his silky, dyed-black hair smoothed over. There was nothing as uncomfortable as seeing those stunted fat fingers jutting out of a short arm in greeting — palms permanently wet from sweat and grease, just like his real self. He was loud-mouthed, vulgar and ate and drank noisily. He wore expensive suits, and so he liked to eat wearing an apron that worked like a child’s bib. It was hard to believe that he once was a promising boxer whose dreams were destroyed by the multiple Ethiopian wars.

Can Themba — the South African journalist who died by the bottle in apartheid South Africa — famously said that there are some people whose names just do not go with ‘Mister’, like Mr. Jesus. And there are people who go by both their names, like Muhammad Ali. With Mr. Selassie, no one knew his first name, and it just did not feel right to call him Selassie. I guess it was the respect due a man who, even in the quietest or happiest of times, was a bit scary — like the formality would someday pay off, and he would break one of your arms instead of both.

‘As my people say, “Just because a man’s fingers are too short to play a guitar does not mean he does not know good music,”’ Miriam said, to my laughter, then moved on to another customer. That was another thing about Miriam: she had a talent for making up proverbs on the spot.

‘What is Tizita to you?’ I asked her after she came back to me.

‘You are asking the wrong question,’ she said, and waited for me to ask the inevitably right question.

‘What is the right question?’

She high-fived me, laughing as her wet hands sprayed some of the soapy water around us.

‘With the Tizita, there has never been a competition; it is degrading to the musicians. It is like asking who has a better heart, a better soul — how do you measure that? That is the question,’ she answered.

‘It is human nature — you want to know who the best is. Don’t you agree?’ I asked.

‘We shall find out soon,’ she replied. With a wink, she asked, ‘You know the most important invention in music?’

‘The electric guitar,’ I answered immediately. Bob Dylan, moving from acoustic guitar to electric — I could not sing or play a whole Dylan song, but even I knew the story.

‘No,’ Miriam said. ‘You are wrong — like you are always. Let me whisper it in your ear.’

I leaned in and she pulled my ear so hard that I jumped.

‘What the fuck? Just tell me!’ I cried.

‘I just did — your ear. Without the ear, there is no music, no?’ she said, laughing hard enough to need to lean onto the water-filled trough where she rinsed our glasses.

‘Well, Miriam, 100 years of wisdom and you give me the chicken or the egg question?’ I rubbed my ear.

‘But is that really what you wanted to ask?’ With that, Miriam sashayed to another customer who looked like he could use a beer.

‘Why don’t you just tell me?’ I pleaded.

‘You know those stories about soldiers stopping a war to carry their dead and wounded on Christmas or something?’ she asked me as she triaged who amongst her customers was thirstiest.

‘Yes, I have heard the story of how a Tizita musician stopped the Ethiopian-Eritrean war — many times in fact. But it’s a myth; every major war has such a myth. A beautiful woman walking by, football on Christmas, a white dove — it’s just soldiers getting tired of war.’

She reached out for my hand.

‘That musician, he is here tonight — you can ask him. But my answer, you big, spoilt child, is to listen to everyone, and everything.’

She jutted her chin towards the dressing rooms.

Her smile followed my kiss on her cheek as she slipped a fifth of Vodka into my hand.

‘That’s on me — you’re going to need it by the time the Tizita is done with you tonight,’ she said, and playfully cupped a warm, wet hand on my face.

I slipped the fifth into my pocket and took a liberal, or more like a radical, swig from my beer. I did not have time to argue with her about the etiquette of pulling a customer’s ears for a cliché about chickens and eggs — Mr. Selassie was walking into the ring wearing bright red boxing trunks, shoes and a robe with Ali Boxing Club emblazoned on the back.

3

‘Life’s a bitch and then you die.’

‘Welcome to the first ever international Tizita competition!’ Mr. Selassie’s booming, slow-motion voice called the crowd to attention as he began explaining the rules. They were simple enough for the musicians and gamblers — winners would take it all. The winner of the Tizita would be whoever received the loudest applause. The purse was 1 million Kenya shillings, and that ‘invaluable street cred,’ as he put it. Finally, there was absolutely no recording of any kind allowed — and with that, disappointed faces put their mobile phones back into their pockets and purses.

Yes, a million shillings was a good amount of change, but still, why would a successful musician, one considered to be one of the best, come to a place like the ABC? I had heard of successful musicians and bands like Bruce Springsteen and The Rolling Stones occasionally giving up the stadiums and concert halls to play in small neighbourhood bars. A return to the basics, to intimate spaces where they could actually interact with and react to their audience. But that street cred, the million Kenya shillings and playing against the best — was that enough to bring an artist worth their name to a place like the ABC? Or were the musicians slumming the slummers, a two-way spectacle?

‘The Corporal!’ Mr. Selassie announced.

The Corporal, somewhere in his fifties, was tall and thin, with the greying but good hair that we Kenyans envied so much, smoothed back. He was dressed efficiently in jeans, a green shirt with rolled-up sleeves and sandals. His face was confident — gaunt and wrinkling, but still pulled tight by high cheekbones; he could have been an ageing runner or football player. He walked briskly and, using the ropes, he hurled himself onto the stage, picked up a guitar, and finger-picked in a way I had never heard done before — a thudded, muted yet vocal sequence of sounds that felt like heavy raindrops rapidly tapping on a corrugated iron sheet roof. A few seconds of guitar, and he picked up a masenko.

The Kikuyu people sent smoke from a sacrificial lamb high into the sky; if God was listening, it went up straight as an arrow. The masenko is an instrument of prayer that I imagine sent prayer straight up to God, but in the hands of The Corporal, the low bass buzzing notes as he bowed the one-stringed instrument were the devil announcing his presence, the sweetest, most terrifying sound.

‘I have a lot to miss — but when I die, what I will miss the most is music, because music is life. When I die, I hope to ascend to the Tizita, my final resting place,’ he said and then started to sing his Tizita.

He sounded like there was sawdust in his vocal cords. His voice, trembling threateningly over the masenko, started to give way to a fear, an almost defiant fear, and several images flashed through my mind — a man at Tiananmen Square standing in front of an armoured tank; Rachel Corrie in Palestine standing in front of an Israeli bulldozer moments before the driver crushes her; Muhammad Ali, with broken jaw against Ken Norton; and, oddly, an old eagle with a stiff wing flying along a swollen and raging river before expertly diving and emerging with a fish caught in its talons.

He let out a low, long growl that went underneath the masenko, a sound I had never heard before, a voice trying to find footing from a place that was an early memory — the first sound ever made, it felt like — and then he quickly rose above, joined his masenko and closed his Tizita in his soothing falsetto.

Have you ever suddenly found yourself in the dark of the night? I mean, rural absolute darkness? I once listened to a podcast — some astronaut in space out to repair something described the darkness of space as a complete absence of light, so thick he thought he could dip his hand into it like it was oil. That was the masenko, only it was with sound.

But The Corporal was not trying to send us into space, to heaven or hell. He kept us here on our terrifying earth. We wanted to break into tears and jump into the abyss — a catharsis, of course, that would allow us to go back to the morning with all the pain and reminder it brought — but the masenko was not an instrument of flight. It was the instrument of reckoning. If you could hear your voice through the judging ears of a stranger — what kind of judgement would you give? No, we had not come to ABC to hold up mirrors. We were there to escape, and he was not letting us.

The crowd of drunks, gamblers, slummers and swingers — we his degenerate audience — we punished him with tepid applause for denying us escape. He knew what he had done to us, because he shook his head and laughed as if to say, That was only the first round.

It was only when he stood up and started walking to his seat by the ring that I noticed he had a limp.

***

‘And now, ladies and gentlemen…The Diva!’ Mr. Selassie screamed into the microphone.

The Diva walked in, the glow of sparkling whiteness from her diamond studded dress almost blinding, high heels tapping a confident, unhurried rhythm on the concrete floor. And all that to set the stage, it seemed, for her beauty, exaggerated by her being tall, a beauty amplified by her bright-coloured doll-like makeup. She was somewhere between caricature and performer. She climbed onto the stage and slowly wrapped long, silver metallic nails around the microphone next to the piano and adjusted it. She pulled the gold sheet off the piano, sat down and smiled as she looked at the keys. And we waited and waited, waited for a voice, for sound, that first sound, but she kept looking and shaking her head from side to side, as if the thought of playing was dragging her along against her will. She kept leaning into the microphone as if about to start singing before being pulled away by the piano.

In the audience, we started sending each other glances that betrayed our growing doubt and desperation to hear her voice, at least once — to know what she sounded like. But I was tipsy enough to let myself take in what she was offering instead of longing for what I wanted to hear. And then she fell on the piano keys, light as feathers, so that every time she hit a key my body fluttered with her every exertion. Her breath escaping her mouth in small bursts hit the microphone.

I followed The Corporal’s old eagle along the tumultuous swollen river, dipping in and out of the water with her slow trance-inducing touch of the piano keys. But it felt like there was something wrong — her or me, her or the audience, one or the other was in the wrong place — and I pulled out of her world, which was really The Corporal’s, and back into the ABC. I suspected this was The Corporal’s doing; he had set the stage with his Tizita in a way that spoke to the musicians in a language that had gone over our heads.

She seemed to think for a minute.

‘Did you know that there is no sound in heaven and space? Or words? What would music sound like without sound?’ she whispered into the mic, a bit drugged, it seemed. ‘And how would you really sing your Tizita? Or listen to it?’

It felt like the stage could barely contain her, and the pain or anguish of being confined seemed to rise out of her in the low cry she let out to finally start her Tizita. Yes, reading this now, you will think I am being melodramatic, but hearing that cry that started at a high note, then made lightning zigzags, tapping something here and there until she hit the earth with a bass lower than a man’s — to hear that, to feel its vibrations, was to realise what not a just-failed song sounded like. It was to realise there was a lot more to her than what this stage, this night and this competition were allowing, what we were allowing. It was beautiful, this protest that hurt.

She stopped playing the piano altogether and started to sing, and even though she had stopped playing it, I could still hear it. She had suggested the piano and then let us do the rest of the work while she took us through the Tizita, filling in piano keys running fast downhill when her voice soared and letting the keys climb up a steep hill while her voice dug deep into an abyss and dragged us along and beat our bodies against its jagged edges — her glamorous look and her mournful Tizita at odds. And there I felt the tremors of extreme happiness. Then a singular force of all my tragedies — the night when my grandmother died in her sleep after a simple goodnight, my two grandfathers who died before I was born — hit me. My own weight collapsing in on me with the force of a black hole was unbearable. And then she was done.

And whatever that was, it was gone, and bewildered relief set in for all of us.

***

‘The Taliban Man!’ Mr. Selassie announced, even before The Diva left the stage. We went wild. We wanted something to wash our blood off the ring. We were not ready to go where The Diva was taking us. We yelled, clapped and patted each other, bought each other beer, lit cigarettes and nodded at each other vigorously.

The Taliban Man — I was going to ask him what his name meant to him and his fans. A name of defiance, I guessed — for an artist, it made sense — to take on that name meant to subvert its uses, whether it was the actual Taliban or the United States and its war that had now found itself in Somalia and, by extension, Ethiopia. It was the kind of name that, once you heard it, remained seared in your brain and, in time, in the recesses of your subconscious. There were the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan shooting school kids in the head; there were the Americans dropping drone bombs on school kids and weddings in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and then there was The Taliban Man, the rapper musician from Ethiopia. In the ABC, it made its own peculiar sense.

Mr. Selassie laughed into the mic. ‘The Taliban Man!’ he yelled again.

The Taliban Man ran into the ring dressed in a black suit, a black bow tie and military boots into which his black dress pants were tucked. He did a somersault, his tall frame making it look like it was in slow motion. He walked to the piano. He hammered a few keys with youthful energy, and from the chaos, order started to emerge. Ragtime. The little I knew told me that ragtime is classical music played over itself many times at the same time — where each fucking voice has something to sing along to or eventually say. Schizophrenic classical music, but the musician has to give it form, madness contained. The Taliban Man was all of them, and I was sure he would take the cup home. He was asking us, If you were many people with different rhythms, voices, how would you hear yourself? As one? As many? He was playing that many songs at the same time. He hit a few more bars, leaned back and laughed into the microphone as if to say, Just joking.

He left the piano and picked up a guitar — he played an instrumental Tizita, the guitar clean and efficient, walking steadily underneath his voice. Then he broke into it and ran the Tizita faster and slower until he fell onto a lean, steel guitar jazz tune. It was not quite working — it was like the two were clashing, jazz refusing to be contained, but the Tizita beat insisting steadily on being heard. They both overwhelmed each other, and I for one was getting disjointed. He laughed again and lifted up his hands as if in defeat.

He paused and started a slow, major chord-driven Tizita that he drove with a hip-hop beat before breaking into rap. He rapped a few stanzas before asking us in English to clap along and repeat after him:

Life’s a bitch and then you die,

You never know when you are going to go

That’s why we get high on — he taught us how to pause here, letting it hang on before dropping — love.

We rapped along like that for a while, laughing childishly at being able to say the word ‘bitch’ to each other, inflected by our various accents — mbitch, birrtch, biaaatch, bisch and so on. Eventually, The Taliban Man stood up and led us through a roof-raising ‘life is a bitch and then you die.’

He thanked Nas and, buoyed by the applause, hopped off the stage.

4

‘Tizita, What I fear the most is that I will forget this pain that carries my love.’

We were still hungry. We were, in fact, getting hungrier. It was like they were feeding us appetizers and not the whole honey-roasted goat. We wanted more.

‘And now, our very own Miriam,’ Mr. Selassie yelled.

That was a surprise. Nobody, least of all me, knew she could sing, let alone compete with the best of Tizita singers. But it soon started making sense, without any logic behind it. It just seemed right that she too would be on that boxing ring-cum-music stage.

She started looking around, one hand over her eyes, until she spotted me. She beckoned and I walked over and helped her onto the stage — she felt light and frail. After she sat down, she blew me a kiss, looked up at the microphone hanging down and pulled it further down so that it was within her range. She took a deep breath, almost a sigh, into the silence that had followed her every move. At that point we, her crowd of loyal customers, came to life and started cheering her on. She raised her left eyebrow and put her right arm out, and we quieted, recognising her usual signal for when one was in danger of being cut off at the bar.