Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

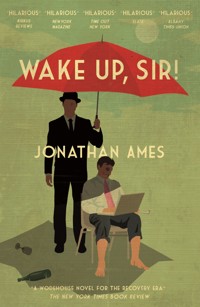

Alan Blair, the hero of Wake Up, Sir!, is a young, loony writer with numerous problems of the mental, emotional, sexual, spiritual, and physical variety. He's very good at problems. But luckily for Alan, he has a personal valet named Jeeves, who does his best to sort things out for his troubled master. And Alan does find trouble wherever he goes. He embarks on a perilous and bizarre road journey, his destination being an artists colony in Saratoga Springs. There Alan encounters a gorgeous femme fatale who is in possession of the most spectacular nose in the history of noses. Such a nose can only lead to a wild disaster for someone like Alan, and Jeeves tries to help him, but... Well, read the book and find out!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 553

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Wake Up, Sir!

“Out-Salingers Salinger… Ames’s own comic ululations resonate long after you finish the novel.”

—New York Post

“What do you get when you cross Carry On, Jeeves with Portnoy’s Complaint?… Jonathan Ames’s very funny new novel, Wake Up, Sir!”

—Newsday

“Ames is a remarkable comic writer. He excels at punching out hilarious monologues on subjects ranging from nose fetishes to the planks of Buddhism.”

—Time Out New York

“Wake up, Sir! takes on the big themes—the homosexual question, the Jewish question, the great American novel question and more in this witty, wild romp… Comic and incredibly accurate.”

—A. M. Homes, author of May We Be Forgiven

“Dirty but erudite… A hilarious romp… wielding preemptive irony like a blunter, more frankly libidinal Dave Eggers.”

—New York

“So brilliant and charming that any description of it is bound to be impossibly dull by comparison.”

—Seattle Weekly

“Hilariously bizarre.”

—Esquire

“[An] inventive romp.”

—The New Yorker

“Oh, and the sex in the novel is really fresh, with the quiver of first times. Which is nice to read, repeatedly.”

—Jane

“Here is a book, rigorous as a dream and well ventilated with wit… a classic of caprice.”

—The Village Voice

“[A] deliciously dry martini of a novel.”

—O Magazine

“Cause for celebration… Ames can produce a pretty good facsimile of Wodehousean badinage, some of it sharpened to a twenty-first-century edge… As Jeeves himself might prompt Ames, ‘Carry on, sir!’”

—The Washington Post

“Very funny and altogether elegant, this tale of an endearing drunk and his unflappable manservant is a love story of sorts, but with an American twist. Here, a valet is just a friend one pays.”

—Sarah Vowell, author of The Partly Cloudy Patriot

“An ingenious and bizarre blend of Catskills comic and arch British satirist… Ames is as substantial as he is loony.”

—Philadelphia Weekly

“Too funny for the canon of high literature, the book is too brilliant to be mere diversionary humor.”

—New York Press

“A hilarious journey into one man’s labyrinthine neuroses, with day trips to compulsion and delusion. The perfect gift for anyone who has ever imagined having a manservant.”

—Colson Whitehead, author of Zone One

“Pungent and hilarious, if completely off the deep end.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Ames’s tale zips along, brimming with comedy and wild details, proving him to be a winning storyteller and a consummate, albeit exceedingly eccentric, entertainer.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Hilarious… belly-laugh humor… Ames is a humorist for our age.”

—Arkansas Democrat-Gazette

WAKE UP, SIR!

JONATHAN AMES

For Blair Clark and Alan Jolis (in memory)

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following individuals and institutions: Priscilla Becker, Brant Rumble, Rosalie Siegel, Conjunctions magazine, the Guggenheim Foundation, the Medway Foundation, and the Corporation of Yaddo.

Contents

“Live and don’t learn—that’s my motto.”

—ALAN BLAIR

PART I

Montclair, New Jersey

CHAPTER 1

Jeeves, my valet, sounds the alarm * A physical description of my uncle Irwin, the gun fanatic, and a rundown of his morning regimen * I rush through my toilet and yoga * A delayed ejaculation of fear

“Wake up, sir. Wake up,” said Jeeves.

“What? What is it, Jeeves?” I said, floating out of the mists of Lethe. I had been dreaming of a gray cat, who, like some heavy in a film noir, was throttling in its fists a white mouse. “I was dreaming of a gray cat, Jeeves. Quite the bully.”

“Very good, sir.”

I started slipping back into that cat-and-mouse confrontation. I wanted to see the little white fellow escape. It had very sweet, pleading eyes. But Jeeves cleared his throat respectfully, and I sensed an unusual urgency to his hovering presence which demanded that the young master rally himself from the luscious pull of dreams. Poor mouse would have to go unsaved. No happy ending.

“What’s going on, Jeeves?” I asked, casting a sleepy eye at his kind but inscrutable face.

“There are indications, sir, that your uncle Irwin is no longer asleep.”

It was only under these alarming circumstances that Jeeves would interrupt my eight hours of needed unconsciousness. He knew that the happiness of my morning was dependent on having as little contact with said uncle as possible.

“Groans from the bedroom, Jeeves? He no longer dreams—probably of firearms—and is staring at the ceiling summoning the courage to blight another day?”

“His progression into the morning is further along than that, sir.”

“You heard his feet hit the floor and he’s sitting on the edge of the bed in a stupor?”

“He’s on his stationary bicycle and he’s davening, sir.” Jeeves had picked up the Anglicization of the Yiddish from me, adding the ing to daven (to pray) as I did.

“Good God!” I said. “This is desperate, Jeeves. Calamitous!”

Coming fully awake and now nearly at the height of my sensory powers, I could make out the spinning of the bicycle’s tires, as well as my uncle’s off-key Hebraic singing—his bedroom was just fifteen feet away down the hall.

“Do you think there’s time, Jeeves?”

“There is very little room for error, sir.”

I am usually unflappable and rather hard-boiled, if I may say so, but this predicament first thing in the morning shook me to the core. For several months now, with rigorous discipline, I had just about managed never to see my uncle before noon.

“How has this happened?” I asked. I didn’t want to fault Jeeves, but he had never before let my uncle get so far as the stationary bicycle without awakening me.

“Your uncle has risen quite early, sir. It is only eight-thirty. If you’ll excuse me for saying so, but I was performing my own toilet during the first stages of his morning program.”

“I see, Jeeves. Perfectly understandable.” I couldn’t expect utter vigilance from the man—after all, he was my valet, not a member of the Queen’s Guard—and my uncle had thrown everything off by getting out of bed more than two hours ahead of schedule. This was an anomaly beyond the palest pale, and so our best defense—Jeeves’s keen eavesdropping—had been wanting.

Well, I was in a bad way, but I like to think of myself as a man of action when shaken to the core, and so I threw back my blankets. Jeeves, anticipating my every move, handed me my bath towel, materializing it from his person, the way he is apt to materialize things from his person when they are needed, and so I dashed out of my lair, wearing only my boxer shorts, and shot myself into the bathroom, which is right next to my uncle’s bedroom.

I had my own morning program to adhere to, but I was going to have to rush through it if I wanted to avoid my nemesis. Hurrying did not appeal to me—I would probably feel anxious the whole day—but an encounter with the ancient relative before noon would be worse. Then all my nerves would be completely unraveled and the day would be lost.

To avoid such an eventuality, Jeeves and I had memorized, in order to map out my every move, my uncle’s morning schedule, which was as follows:

(1) Uncle Irwin’s wife, my aunt Florence—my late mother’s sister—would leave at dawn to go teach special education at the local high school, and she did this year-round, teaching summer school, as well. She was in her early sixties, but still working very hard—an angel in human form. My uncle would say good-bye to her each morning but immediately fall back to sleep. He was in his early seventies and a retired salesman of textile chemicals, though in the afternoons he peddled ultrasonic gun-cleaning equipment to police stations. My uncle was a firearms expert and the house was equipped with a small arsenal. He was ready for another Kristallnacht or a siege by the FBI if there was a repeal of the Second Amendment. In case of a surprise attack, guns were hidden all over the place—behind shutters, in heating ducts—and he often wore a gun in the house, utilizing a special hip-holster. He called this packing, which has metaphorical resonance, I understand, in the homosexual community as well as in the NRA, which makes perfect sense since there is nothing more phallic than a gun; even phalluses seem less phallic, though, of course, the phallus did precede the firearm.

(2) Around ten-thirty each morning my uncle would awaken. He would groan several times and yawn lustily—his large stomach acted acoustically as a sort of bellows. He was a short, round man with a coal black mustache and a very white beard, and this unusual bifurcated arrangement of his facial hair gave him an uncanny resemblance, despite his Jewish origins, to a Catholic saint-in-waiting—a certain Padre Pio. This was discovered when a sweet and pious Italian woman nearly fainted at the local Grand Union and pressed upon my Uncle Irwin a laminated card with an image of this Pio. My uncle then wrote to a Catholic organization and got his own such card, which he kept in his wallet as a form of identification, flashing it if he was in a playful mood at the synagogue or the shooting range or any of his other haunts. Pio was on the verge of sainthood due to his having stigmata—bleeding from the palms—and my uncle said that his carpal tunnel syndrome, brought on by years of clutching a steering wheel as a traveling salesman, was his stigmata.

(3) So after two to three minutes of these nerve-rattling, church-bellish yawns, whose purpose was to deliver oxygen to his organism, the blankets were thrown off. He would then turn on a small mustard-colored radio, which only picked up one station—a round-the-clock government weather report. The broadcaster’s voice was dreary and unintelligible, and it enthralled my uncle for a good five to ten minutes each morning.

(4) Having then been apprised of the current meteorological conditions, he would go to the bathroom and pass water.

(5) After flushing, he’d come back to his room and begin to pray—on average about fifteen minutes.

(6) After prayer, he bathed—ten minutes.

(7) After bathing, around 11 A.M., he was down to the kitchen for his breakfast: microwaved oatmeal, banana in sour cream, hot water with lemon. He ate this hearty meal while reading The New YorkTimes and listening to CBS news on the kitchen radio, which was played at maximum volume. The breakfast, due to the enormity of The New York Times, sometimes lasted as long as two hours, at which point he’d head out for the day to mix with the constabulary and speak of the benefits of keeping the barrel of one’s gun free of dust and oil.

Well, that’s the schedule—so if I played my cards right, I had bathed, breakfasted, and was safely sequestered back in my room before he even reached the kitchen table. Granted, the explosive radio-playing of CBS was unnerving and did not respect the boundary of my bedroom door, but at least there was no physical contact between myself and the relative. To feel properly aligned, mentally and physically, not to mention avoiding being shot or pistol-whipped, I needed solitude in the morning. You see, solitude is essential to producing art, and art in my case was literature: I was writing a roman à clef and needed to be left alone. Jeeves was about, but Jeeves was trained to be invisible. They teach you that at valet school.

Sometimes, though, if I was a little off my program, my uncle and I would pass each other on the three-step staircase that led from the kitchen to the bedrooms—it was a small, two-story, Montclair, New Jersey, house—and this was disquieting, but not the end of the world. He’d shoot me a withering glance full of disapproval, but the lighting was poor on that staircase, and so his mien undid me a little but not completely.

What was bad—avoided at all costs—was to be in the kitchen when he began to eat. Not only would he paralyze me with numerous withering glances, his eyes exuding all the compassion of iced oysters, but he generated in me an irrational reaction to the concussive sounds of his chewing. Without any doubt, the noises he made were obscene, but my response was uncalled for. I was his houseguest—well, practically a permanent resident for the last few months; he and the aunt had taken me in during a difficult time, acting like parents; I was only thirty, relatively young, but my mother and father had been deceased for many years—and so I should have been more tolerant of Uncle Irwin, but I found myself completely unraveled by the slurping cries of a sour-cream-soaked banana meeting its doom between his crushing molars and lashing tongue. Listening to him eat, my spine turned to jelly and I couldn’t think straight for hours, which is why I had so precisely mapped out his schedule—the relative had to be avoided!

So, on the morning in question, the third Monday in the month of July, year 1995, I was in the bathroom, massaging my chin, and I decided I didn’t have time to shave because of the crisis at hand, though it would be the fourth day I hadn’t shaved—the old spirits had been a bit low, and when the spirits are low, I seem to lack the moral wherewithal to remove my whiskers—and a reddish beard was beginning to announce its presence. Meanwhile, my uncle was still singing and the bicycle wheels were whooshing.

But I wonder if I’m being clear about this bicycle business. I should explain that it was an eccentricity of my uncle’s that he did his davening while on his stationary bicycle, which was actually a blue girl’s bicycle that he had found at a garage sale and which had some kind of apparatus restraining its wheels so they didn’t touch the carpeting of his bedroom floor. It was a speedless two-wheeler and provided very little resistance or exercise. He had been pedaling on it for years and was as stout as ever. But at least he made an effort. And he prayed. And though he wasn’t an Orthodox Jew, he wore official davening gear: about his shoulders was his silky, white tallith with its blue stripes and fringes, and on his left arm and on his forehead were his tefillin—the leather boxes and straps favored by Jews for their morning prayers. The boxes, like a mezuzah, contain the Shema, God’s directions to Moses, found in Deuteronomy. One of the lost directions, according to Jewish lore, is “Don’t go out with a wet head!” Luckily, this important health command has been orally maintained for thousands of years.

So my uncle was bicycling and praying, and his tallith, had he been on a real bicycle facing the wind and the elements, would have been flapping behind him like a cape. I estimated that he was halfway through his prayers, and I quickly doused myself in the shower. Usually, I enjoyed lolling in the tub for a good fifteen minutes—a meditative Epsom-salts bath was the first station of my morning schedule—but this had to be forsaken.

With limbs still damp, I then sprinted to my room, towel wrapped around me, and just as I was closing my bedroom door, my uncle’s door opened and in he went to the bathroom. A narrow escape.

Jeeves had laid out my clothes on the bed—soft khaki pants, green Brooks Brothers tie designed with floating fountain pens, and white shirt. My usual writing garments.

“Thank you, Jeeves,” I said.

“You’re welcome, sir.”

“Nearly collided with the relative in the hallway, don’t you know. Another thirty seconds in the shower, and all would have been different. Interesting the way fate works that way, isn’t it, Jeeves?”

“Yes, sir.”

I sensed a certain chilliness in the man, but pressed on with my theory. “All our lives we’re saved from the hangman’s noose by mere seconds, Jeeves.”

“Yes, sir. If I may point out, sir, you have not shaved for four days.” The source of his glacial attitude was revealed.

“I would have shaved today, Jeeves, but I’m economizing my every movement. We have at best ten to fifteen minutes in which to operate.” I could see that Jeeves was still wounded. I tried to explain: “My uncle has thrown everything off by rudely changing his schedule. I’ll shave tomorrow, I promise.”

“Very good, sir.”

I had soothed the fellow, and then I quickly pasted on my raiment, but I eschewed the tie.

“Your necktie, sir,” Jeeves said.

“There’s no time, Jeeves.”

“There is always time for your necktie, sir.”

“I can’t risk it,” I said.

“Your uncle is only just now drawing his bath, sir. I believe there is time enough.”

“No, Jeeves,” I said. “Also I’ve been meaning to tell you that I don’t like doing my yoga while wearing my tie. Especially this time of year with the heat. From now on, I will put on the tie after breakfast.”

“Yes, sir,” said Jeeves. First the shaving and now the necktie. The man was cut to the quick, injured at his valet core. This was clearly a rough morning in our domestic life, poor old Jeeves, but he was going to have to show more sangfroid.

I flung open my door, raced down the stairs, flew through the kitchen, and ejected myself out the front door onto the small patio.

It was here that I performed my yogic exercises. My whole morning regimen (bath, yoga, no contact with uncle) was about achieving the right frame of mind—the correct mental pH, as it were—to toil at my novel. Usually, I did ten sun salutations. These really get the blood sloshing. You’re continually going from standing upright to lying on your belly, then standing up again. What I would do was face east, prostrating myself to the sun, which penetrated through the tops of the summer trees, lighting up thousands of green, eye-shaped leaves. My uncle’s house was nestled quite nicely in a bit of secluded woods—very beautiful New Jersey, I’ve always said, a most unfair reputation. Of course, I’m biased, having grown up in the Garden State.

Due to the crisis that morning, I reduced the number of salutations to one. Then I lay on my back on the patio, which my aunt swept frequently, so there was no danger that my pants would be soiled. I closed my eyes and counted ten breaths. I always do this after sun salutations. I find that meditating on the back is more conducive to peaceful feelings than sitting in the lotus position.

I would like it, though, if I could sit in meditation like Douglas Fairbanks Jr., with my legs crossed at the knee, a thin mustache on my lip, and myself looking very dashing, but I don’t think the soul, which operates like a chimney flue, has much draw when the legs are crossed like that.

Anyway, braced by my one sun salutation and my ten seconds or so of meditation, I went into the kitchen and Jeeves was there, beaming in at the precise moment that I made my entrance, which he’s very good at. He’s always appearing and disintegrating and reappearing just when the stage directions call for him.

“What’s the status of the opposition, Jeeves?” I asked.

“Your uncle is dressing, sir. His attitude is that of one who has an appointment of some sort for which he is expected shortly.”

“You mean to say that he’s rushing off somewhere?”

“Yes, sir.”

“No doubt some emergency meeting of the National Rifle Association or the Jewish Defense League.”

“Perhaps, sir.”

“I think I’ll have to dine in my room, Jeeves. It’s not pleasant, I know. But it’s our only chance.”

“I am in agreement, sir.”

All I liked to have in the mornings in New Jersey was a cup of coffee, toast with butter, a glass of water, and the sports section of The New York Times—not to eat, naturally, but to read. I enjoy nothing more than to sit peacefully at a kitchen table, memorize the baseball statistics, and nibble my humble piece of toast. But this morning that would have to be sacrificed.

My aunt Florence, as she often did, had left a pot of coffee for me, and so I quickly filled my favorite blue Fiestaware mug and then tucked the sports section under my elbow—my uncle didn’t read the sports and so he wouldn’t notice its absence. Jeeves gathered a plate with some cold bread and butter. From the kitchen we charged up the three small stairs, myself in the lead, Jeeves picking up the rear of the formation. I was nearing the summit, on the second step, quite close to safety—my room just one more step and a yard away—but my uncle, unseen by me, was also thrusting toward the head of the stairs from stage right. And so it was only a mere half second later—into the hangman’s noose after all!—that the unfortunate congress took place.

The physics was this: my head, in the lead of my body, was rising up the stairs, breaking the plane of the landing, just as my uncle was hanging a hard and hurried left down the stairs, with his belly, in the lead of his body, breaking the same plane. Two broken planes. A midair collision.

The nose of my plane went into his fuselage with not a little force. The wind was knocked from him, he breathed in caustically, and while his stomach collapsed a little, my neck, weak stem that it is, was forcefully and painfully shoved down into the shoulders. I also took right into my nostrils a dusting of baby powder which was emitted from his person, like a toad of the Amazon squirting poison when stepped on. The relative, you see, liked to generously coat himself with Johnson’s powder after being in the tub, and I had grown to be mildly nauseated by its aroma. So taking that powder directly into the nostrils, right to the center of my olfactory glands, was quite the blow. Somehow, though, I righted myself on the second step, shakily holding the small banister, and miraculously, my coffee had not been spilled. Jeeves transported himself back into the kitchen.

“You idiot!” my uncle aspirated out of his Padre Pio beard. “You klutz!”

Then I, as often happens to me in moments of extreme stress, had a delayed spasm and ejaculation of fear. Whenever I’m scared, I register the scary thing for an instant rather calmly or sleepily: Oh, look, a rat has raced up my leg, I’ll remark to myself—which actually happened to me one time in New York City, a trauma I’ve never quite recovered from—and after the rat reverses direction, having discerned that I am a person and not a drainage pipe, and runs away, I suddenly realize what has transpired and scream at the top of my lungs.

So about two seconds after my uncle bellowed “You klutz!” when essentially the coast was clear, it was then that I responded:

“Noooo!” I yowled inanely, and threw my arms up to protect myself, much too late, and discharged from my person—behaving like my uncle’s baby powder—was my cup of hot coffee, undoing the miracle of just moments before. The coffee spread itself like a searing, brown blanket on his yellow sport shirt, which, because of its thin material, did not prevent him from being scalded.

“Goddammit!” he cried in pain, pawing at his belly.

“I’m so sorry!” I said, mounting the last step, while my uncle recoiled.

“Am I burned?” he half demanded, half whimpered, as he pulled off his shirt. No one deserves to be showered with coffee. Not even frightening uncles.

I bent toward his belly to observe, and there was a thick, protective covering of hair on the stomach, much of it gray and a good deal of it white from the powder, and the skin beneath the hair and the powder seemed to be fine. A little pink, perhaps, but not the violent red of a serious burn.

“I think you’re all right,” I said, wanting to beg for forgiveness, but he retreated to the bathroom, his shirt in his fist like a rag, and I trailed behind like a fool. He regarded himself in the mirror and took a wet washcloth and held it to his stomach. He was rallying rather quickly. Hardy old thing. We regarded each other in the mirror. My thinning blond-red hair looked very frail, matching my mental state, and his mustache, like a mood ring from my 1970s youth, seemed to blacken further. And his eyes were as small as a lobster’s, which is very small. Out of them shot death rays. Usually, as I indicated earlier, his preference was to have eyes that resembled chilled oysters, which was bad enough. So for him to switch over to lobster eyes was not a good sign—his repertoire of withering glances, taken from the worlds of mollusks and crustaceans, was expanding to keep up with his antipathy for me.

“I’m sorry I’m such an idiot,” I whispered, and then I oozed down the hall to hide in my room.

CHAPTER 2

I attempt a little scribbling * The subject and hero of my novel are touched upon * Dating practices of wealthy senior citizens are explained in a sociological way * Jeeves, being quite literary, reassures me about the day’s output of prose * I think back on how Jeeves came into my employ * Jeeves makes lunch * I make a decision

Careworn, you might have described me. Distressed and paralyzed would have also worked. I was lying on my bed. Too depressed to eat, I had gone without breakfast. Jeeves flickered like a beam of light to my left.

“Do you think a written apology, Jeeves, might do the trick?”

“I don’t know if that is necessary, sir. It was an accident. Your uncle is not an unreasonable man. And from what you tell me of your inspection of his abdomen, no serious injury occurred.”

“Perhaps you’re right, Jeeves. But it is soupy. You know what they say about guests who overstay their welcome. Perhaps my tenure here has strained the blood ties. But I’ve been selfish, Jeeves. It’s been good for the writing, this New Jersey air. Brings me back to my roots.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Maybe if I run the fingers along the keyboard now, my spirits will improve.”

“You often feel better, sir, when you do a little work.”

“Some iced coffee then, Jeeves. You know I can’t write without it. Aggravating the nerves with caffeine always helps with the Muse.”

“Yes, sir.”

Jeeves trickled out to get the coffee. We knew the coast was clear. My uncle, after the debacle on the stairs, had gone about his usual routine of assaulting a bowl of oatmeal, reading the newspaper, and listening to the radio. When the radio was shut off and we heard the front door slam, we knew that we serfs could run free and frolic and drink vodka and grab female serfs and sleep on the haystacks.

I sat at my desk and presently Jeeves arrived with my drink. I sipped the iced coffee and stared at the computer. I had only recently made the harrowing switch from the typewriter to the laptop, but there were decided benefits—one could play solitaire on the computer during momentary lapses in the creative process.

My first novel I hadn’t even typed—I wrote it by hand and then gave it to a typist. But this was several years before. I had published rather young, only twenty-three, just a year out of college, but now at age thirty, while still a young man, I was practically washed-up. Hence my obsession with avoiding the uncle in the morning and being in the right frame of mind for writing. If I didn’t produce a second novel, I would be a one-hit wonder. As it was hardly anyone read the book, I Pity I, but it was published by a major New York house, and so in my own little world I had something to live up to.

This new novel, which I had been working on for two years, was, as I mentioned, a roman à clef, except all the clefs weren’t famous or celebrated in any way, except in my opinion. And I guess this is a bit strange since romans à clef are usually about well-known people, but it was a style that appealed to me—the protective covering of fiction over the caprice of real life. I hadn’t yet changed people’s names, except for my own, calling myself Louis instead of Alan. I’ve always been irrationally fond of the name Louis.

So the narrator of my novel was Louis (me), but the real hero of the story was my former Manhattan roommate, Charles, whom I planned to rename at some point Edward or Henry, thinking it was smart to stick with the names of British kings, especially since Charles was a real Anglophile and follower of the royal family. He was also an acerbic, failed playwright, but I thought he was brilliant. Unfortunately, no one else shared my opinion, only an obscure critic or two back in the fifties, and so he was a nearly penniless senior citizen, which is why he needed a roommate.

Charles did have some income from teaching composition at Queens College and from his monthly Social Security check, but it was barely enough to live on. I had the lofty ambition that though Charles’s plays had failed to make him a great American writer, I would make him a great American character. So while living with him, I was writing about him, though he didn’t know this—I worked on the book at the Ninety-sixth Street library or in the apartment when he wasn’t home, and I kept my notebooks and the manuscript well hidden. I was always secretly jotting down things he said—his dialogue was wonderfully rich—but the ethics of the whole enterprise disturbed me: the act of stealing someone’s life. And yet I didn’t stop. I was driven by an imperious need—I had to produce a second novel!

After nearly two years of being roommates, we had a bad falling-out, and this led to my moving to New Jersey and taking up residence with the aunt and uncle. But I continued to view the book, which Charles was still unaware of, as an extended platonic love letter. You see, I greatly admired the man, despite the ending of our friendship, and my admiration was akin to love.

My title for the roman à clef was The Walker, since Charles was a walker for several wealthy Upper East Side ladies. This was a way for him to get some good free meals of the highest quality, which he very much enjoyed and couldn’t have afforded otherwise.

As a walker, Charles didn’t have to pay, because in the upper classes, as men and women get older, the roles, quite often, reverse: where once the man always paid, the woman now pays. These upper-class women in their seventies, eighties, or nineties have usually outlasted more than one husband, either through divorce or attrition (women live longer than men), and so they inherit and accumulate great wealth. The problem is they can’t really attract new husbands or lovers or even more likely they don’t want new lovers and husbands, but it is nice to have a man around, looks good socially—he opens doors, pulls out your chair, carries the luggage on trips—and so these wealthy women, these survivors, need male companionship. Thus, hovering around them, like blue-blazered seagulls, is always a roster of men who have no money, but do have a certain sophistication, which means they’re quite often homosexual. “Walkers” is what they’re called, seemingly because they walk alongside the woman, providing support. Sometimes they’re referred to as an “extra man,” as in you might need an extra man to complete the seating arrangements—boy, girl, boy, girl—at a dinner party.

It all works out rather well, because these men, these poor gay senior citizens, like their lady friends, can no longer attract lovers, but they’re not alone—they find themselves, in their latter years, with women. The whole thing comes full circle: these men, these walkers, are engaging in sexless heterosexual dating, just as they must have fifty, sixty years ago when they were in the closet, which is where most homosexual men of that generation could be found.

So Charles was a walker and had the necessary costumes—one set of evening clothes and a variety of blazers, none of which were in good condition, but his ladies didn’t notice as their cataracts were usually quite advanced.

I should mention that Charles wasn’t clearly homosexual, despite my general depiction of a walker’s attributes. Charles was very discreet on the subject of his sexuality, didn’t think it was my or anyone else’s business, and so none of my vampiric prying could get a disclosure, even after living together for two years. I was shamefully curious—as most people are—about what I shouldn’t have been. But I guess we all like to know other people’s secrets so that we can live with our own. Charles, in retrospect, was perhaps something quite rare, a heterosexual extra man, though in truth he seemed to be against all sex, which is a position not without merit.

Well, that gives you a general idea of the book I was working on—a portrait of a walker as an old man, and his worshipful sidekick, Louis (me). So there I was in New Jersey, sipping the iced coffee Jeeves had provided, and I picked up the novel where I had left off the day before. I slowly typed the following scene:

I was lying on the orange carpet and watching television. I was happily absorbing a Western. There was a big shoot-out going on and lots of horses were rearing up on their hind legs and kicking up dust, which made it hard for the gunslingers to see one another. The battle was rather long and protracted, and Charles came home in the midst of it, saw what I was watching, and didn’t approve.

“Guns!” he said. “Americans are always shooting guns. They can’toutwitanyone, so they shoot them…. Put the news on. I can’t stand Westerns. I want to see what’s happening with the Saint Patrick’s Day Parade. I wonder if this year it will finally be canceled.”

I switched the channel with the remote control. Charles took off his winter coat and poured himself a glass of his cheap white wine. “Do you want some?” he asked.

“Yes, thank you,” I said greedily, sitting up. He handed me a glass of the yellow-colored wine and sat on his couch. The sports segment of the news was being shown; it was eleven twenty-five.

“I don’t think there will be anything about the parade,” I said. “All the real news has already been broadcast. Now it’s just sports and weather.”

The sports report came to its end and then we gloomily watched the weather forecast—an ice storm was expected. Spring was a week away, but it was slow in coming. I turned off the TV.

“The homosexuals are trying to wreck the parade again,” said Charles, sipping his wine. “Every year they protest and they take all the joy out of it for the Irish-Catholics. Gays have no tolerance for others’ points of view. Why can’t they accept that Catholics think homosexuality is a sin? They say, ‘You can march in our gay pride parade.’ But they wouldn’t allow someone carrying a sign that says, ‘Sodomy Is Wrong.’ So why should an Irish-Catholic let someone carry a banner that says, ‘We’re Irish and Gay and Proud of It’? And there’s nothing to be proud of. It’s to be endured privately.”

“Are you going to watch the parade if it happens?” I asked.

“No, I can’t stand parades. Too many ugly people.”

“What do you think of this, Jeeves?” I asked, and he evaporated and then reconstituted himself alongside me. Looking over my shoulder, he quickly read what I had produced.

“Do you think I have too much sitting down, passing of drinks, and taking off of coats?” I asked before he could comment. “Am I clogging things up? Seems like my characters are always walking across rooms and opening doors. Why can’t they just appear places? And if I’m going to have all this movement, I should at least have a fistfight, don’t you think, like in Dashiell Hammett?”

“Writing, I imagine, sir, is like seeing,” said Jeeves. “You see the characters sitting and drinking and taking off their coats and so you have to describe it. And, furthermore, I don’t think you have slowed down the narrative thrust with these necessary descriptions.”

“But talking about the Saint Patrick’s Day Parade is not very lively.”

“I find it, sir, to be an amusing anecdote, and revealing of character.”

“Thank you, Jeeves,” I said gratefully. I felt rather fortunate. Not too many writers have valets who are of the literary sort. In fact, Jeeves and I were reading together, as a sort of two-person book club, Anthony Powell’s epic, twelve-volume A Dance to the Music of Time. It’s absolutely a stupendous work—almost nothing of moment occurs for hundreds of pages, thousands even, and yet one reads on completely mesmerized. It’s like an imprint of life: nothing happens and yet everything happens.

Anyway, when I’d hired Jeeves just five months before, in February, I had no idea he was bookish. There was his very literary name, of course, but this didn’t make me think he was an avid reader, it merely threw me for one hell of a loop. I mean, who ever heard of a valet actually named Jeeves? That’s outrageous! That’s like looking for a private detective in the Yellow Pages and stumbling across Philip Marlowe! What was the likelihood?

We all have cultural blank spots—I, for example, despite having grown up in the seventies, cannot distinguish the music of the Rolling Stones from that of the Who, though I am, through osmosis, aware of these rock bands—so some people might not know that P. G. Wodehouse, the premier British comedic writer of the twentieth century, wrote a celebrated series of novels about a young, wealthy idiot named Bertie Wooster and his wildly competent and brainy valet named Jeeves! I repeat: a valet named Jeeves!

So my hiring someone called Jeeves to be a valet is a stunning, improbable coincidence. And, you see, what makes this even more remarkable is that during the dark month of January, my first month with the aunt and uncle, I had fallen into a morbific depression and so had prescribed to myself the cure of reading lots of Wodehouse. I was using Norman Cousins as my role model because I had once heard on the radio that Cousins had healed himself of cancer by overdosing on comedic films—probably Chaplin, Keaton, the Marx Brothers, and Laurel and Hardy—and laughing himself into wellness.

I substituted an overdose of Wodehouse as a remedy—I’m more of a bibliophile than a cinephile—and it worked pretty well. By early February I had inched from black-lungish melancholy to drooping spirits. Then something really morale-boosting occurred: a check for $250,000 arrived with my name on it. Now, you don’t see checks like that every day. For that matter, you don’t see them every lifetime.

How this check had come into my possession was that two years before I had slipped on some ice in front of a Park Avenue building and broken both of my elbows—a disaster for a writer who needs his arms to type, but very good for a lawyer, a lawyer who likes to sue, and I found such a lawyer—Stuart Fishman. So two years later, rather quick for such things, I had been awarded $250,000—after Fishman took his well-earned $75,000—by the owner of the building because the doorman should have salted the area where I fell.

Well, there I was coming out of a depression thanks to that check and my reading cure, and I have to say I was sort of delirious from absorbing so many Wodehouse novels. He wrote ninety-six and I digested forty-three of them, including all fifteen of the books that feature Wooster and Jeeves. And this delirium produced an unexpected thought: Why don’t I hire a valet? For years, I had lived frugally off the inheritance from my parents’ early deaths, and that money had just about run out, but now I was a rich, young quarter-millionaire! Why not have a valet?

I mentioned the idea to Uncle Irwin since, after all, I was living in his house, and he remarked rather forcefully, “You’re insane!”

So I dropped the matter, but then a few days later, in a rare act of willfulness, I called a domestic-help service, while Uncle Irwin was out selling gun-cleaning equipment and Aunt Florence was at the high school. The service promptly sent me Jeeves and I was immediately impressed by the man, but when he told me his name, I was taken aback and said to him distrustfully, “Did you change your name to Jeeves to bring in the business?”

“No, sir,” he said. “Jeeves has long been my family name, since before my grandparents emigrated to this country from England.”

“You’re American?”

“Yes, sir.”

“But you sound English to me.”

“I have, sir, what you would call a Mid-Atlantic accent, which is sometimes mistaken for an English accent.”

“Yes, you’re right. I hear it now. But, anyway, it’s awfully odd that you’re named Jeeves, if you know what I mean. It’s throwing me for a bit of a loop.”

“I can appreciate, sir, your reaction. I imagine that you are making reference to the character Jeeves in the novels and stories of P. G. Wodehouse.”

“Yes, that is what I’m making reference to!”

“Well, all I can tell you, sir, is that it has long been the theory in my family that the young P. G. Wodehouse must have encountered a Jeeves or a Jeaves with an a, in which case he changed the spelling for legal reasons, but, regardless, he thought it a good name for a valet and went on to use it with phenomenal success, but to the detriment of real Jeeveses everywhere.”

“I see.” I didn’t say it, since I didn’t think it was my place, but I wondered if Jeeves had gone into valeting out of desperation. A sort of “if you can’t beat them, join them” approach, like being named Roosevelt and feeling compelled to run for president. “Have you considered changing your name to ease the burden?” I asked.

“No, sir. Regardless of the circumstances, one takes a certain pride in one’s family name.”

“Yes, of course,” I said, and as Jeeves explained all this, it made me wonder if Frankenstein had once been a common German name, and then I recalled a fellow at Princeton, my alma mater, named Portnoy, who got a lot of razzing. So Jeeves wasn’t alone with this kind of name problem, and his explanation about the whole thing was certainly sympathetic and calmed any thoughts I had that he might have been some kind of conman/valet. Thus, I was ready to hire him on the spot—he was everything I was looking for, there was about the man an aura of serenity and competence—but I thought I had better not appear too eager, so I pressed on with my interrogation.

“Well, thank you for clearing up this name issue…. So, do you have any allergies I should be made aware of?”

“No, sir.”

“Do you belong to any political groups or apolitical groups?”

“No, sir.”

“Clubs?”

“No, sir.”

“Do you have any hobbies?”

“No, sir.”

“No hobbies? Fishing? Leaf-pressing? Bodybuilding? Crossword puzzles?”

“No, sir. I like to read.”

“Me, too! That’s my only hobby, and a weakness for the sports pages.”

“Very good, sir.”

Well, that was it. I was sold. The man was perfect. So, feeling rather omnipotent with my quarter million dollars in the bank, I offered Jeeves the job and he accepted, and thus it came to be that the good old fellow entered my employ.

The aunt and uncle, fortunately, didn’t say a word about it, cowed I guess by my having a servant, and, too, Jeeves was quite expert at staying out of their way. Also, because of my settlement, I started paying my aunt and uncle a generous rent, and this may have helped them to not be bothered by Jeeves’s occupying the other spare bedroom.

So Jeeves was unquestionably a great addition to my life, and the fact that he could help me with my writing was a spectacular bonus. After producing that page about the Saint Patrick’s Day Parade and receiving Jeeves’s kindly stamp of approval, I said, “Well, I think I’ve written enough today, Jeeves, and I’m famished. Can you put something together in the way of nutrition? All I’ve had in my mouth today are my teeth.”

“Yes, sir.”

In no time at all, he fixed me up some sardines, tomatoes, and toast. It was a splendid feast, and afterward I was ready for my nap. Usually after lunch I need to sleep—my constitution and digestion are, in this way, rather Mediterranean in spirit.

I laid my head on the pillow, and though I was quite tired, I found myself worrying about the situation with the aunt and uncle. I really had overstayed my welcome. It was time for me to move on, and in that moment I made an imperial decision.

“Jeeves,” I called out.

He poured into the room. “Yes, sir.”

“Jeeves, how do you like the mountains?”

“I am not opposed to mountains, sir.”

“Well, I was thinking that tomorrow, you and I should disappear for the rest of the summer. We’ll take the car”—I owned a 1989, olive green Chevrolet Caprice Classic—“and motor up to the Poconos. We can rent a cabin and commune with the Hasidic wives of Manhattan diamond merchants, and I’ll work on my novel in that mountain air, which I imagine will be invigorating.”

“A very good plan, sir.”

“After my siesta, start gathering the Blair necessaries. We’ll attempt to break free of Montclair tomorrow. I think you’ll enjoy the Poconos, Jeeves.”

“Yes, sir.”

I was sure my uncle Irwin would be glad to see me go, especially after I had burned him that A.M., but my aunt Florence, I thought, might be against my leaving—she was very fond of me. She’d never had any children of her own, and I think I had become something of a son figure and so I was concerned she might take it hard that I wanted to leave for the summer, if not for forever. But I saw the coffee debacle as a sign for me to move on, because a guest—even one thought of as a son—must know when to leave, even if the guest has nowhere to go.

CHAPTER 3

Dinner at the Kosher Nosh * Why a Jewish predilection for constipation can be lifesaving * A Chinese family momentarily distracts * An unexpected contretemps * A sad good-bye

A few hours after my nap, it was time again for calories and I was at the Kosher Nosh restaurant with the old flesh and blood—Aunt Florence and Uncle Irwin. Jeeves was home, doing who knows what—probably writing letters to fellow valets in servitude in far-off lands. Meanwhile, I was meditatively chewing on a large, wartish, dark green pickle. I had already broached the coffee matter during the car ride to the restaurant, and my uncle, as Jeeves had predicted, was perfectly reasonable and forgiving; so now, with each bite of my pickle, I was gathering up the courage to tackle the next difficult issue—to let the old f. and b. know that their beloved nephew was going to take wing the next morning.

It was part of our normal routine to go to the Kosher Nosh on Monday nights. It was a delicatessen restaurant with about fifty simple tables, all very close to one another, and the whole place was bathed in bright fluorescent lights. On one side of the establishment was the dining area, and on the other was a thirty-foot glass counter filled with all sorts of meats and salads and knishes of various origins, and behind the counter were usually about half a dozen yarmulked, white-smocked countermen, who engaged in playful Yiddish banter and efficient meat-slicing and shouted with authority, “Next!”

The clientele of the Kosher Nosh were ancient Jews who had no business eating pastrami sandwiches. They hardly looked like they could walk, let alone digestively break down noxious smoked meats. But there they were, happily absorbing substantial portions of kosher brisket, corned beef, pastrami, roast beef, chicken, hot dogs, tongue, liver, and steak.

I was as Jewish as any of the alter kockers—that’s “old codgers” in gentile—present at the Kosher Nosh, but my surname Blair (originally Blaum but changed at Ellis Island), and my somewhat Waspish appearance often have me mistaken for a gentile. But my palate—I love pastrami and Cell-Ray soda—in contrast to my looks is a dead giveaway and decidedly Semitic, as is my digestion, which, like with most Jews, is constricted at best. If anyone should be vegetarian, it’s the Jews. But we may have developed constipation in a Darwinian way. We’ve spent centuries hiding in cellars during pogroms, inquisitions, and holocausts, and so if you don’t have to go outside to the bathroom, where you might get killed by a passing Cossack, inquisitioner, or storm trooper, then you live longer and pass on your genes, including the lifesaving constricted-bowel gene.

So every Monday at the Kosher Nosh, I got my weekly pastrami fix, and it was the one communal meal where my uncle’s mastication didn’t completely unman me. The other chewing noises coming from the tables around us were all so ghastly that his noises seemed to be lost in this gruesome chorus; in fact, in the world of the Kosher Nosh, the gurgles and spittles and frothings of his chomping were normal, and so their power over me was somehow nullified.

We placed our order with an exhausted, ready-for-the-grave waitress—for some reason, the Kosher Nosh only hired newly minted female senior citizens; it was a restaurant of the aged serving the even more aged. And it was while I was nervously starting in on a second pickle to pass the time and muster courage that an Asian family of four poked their heads into the dining area. This seemed very unusual. They just stood there, father, mother, a son, and a daughter—all of them clearly uncertain about storming this gathering of Israelites in Montclair. We weren’t a fierce bunch of Jews, but if all the elders wielded their aluminum walking sticks at the same time, we could make a dangerous mob.

“Look,” I said to my aunt and uncle, because of the novelty of the occurrence. “A Chinese family. Or maybe Korean. I don’t think they’re Japanese.”

“They should come in,” said my aunt Florence. “The food here is the best.”

“I wonder what they’re thinking, looking at all these Jews eating corned beef and ready for heart operations,” I said.

“They’re thinking,” said my uncle, “‘must be a good place—there’s Jewish people here—that’s always a good sign.’”

My uncle, despite a number of faults, often displayed a quick and amusing wit, which I admired. I smiled appreciatively at the cleverness of his remark and even let out a little laugh.

But my aunt, who at sixty-three looked no more than fifty with her honey-colored hair twirled in a challahlike, teenagelike braid, did not understand why I had giggled at my uncle’s rejoinder. Her sense of humor, like her braid, was a bit naive, though in all other areas she was bright and sensitive. “What’s so funny?” she asked.

My uncle was momentarily incapable of speech; he had grabbed and was destroying a pickle, nearly swallowing the thing whole—all tables came with an aluminum canister filled with the phallic green wands soaking in brine—and so it was left to me to explain to my aunt. “You know how when we go to a Chinese restaurant,” I said, “or when any Jewish person goes to a Chinese restaurant, and if they haven’t been there before and they see Chinese people eating there, they’ll say, ‘Look! There’s Chinese people—that’s a good sign.’ Well, these Chinese people—if they’re Chinese—have come to a Jewish restaurant and it’s a good sign to them, according to Uncle Irwin, that there are Jews here.”

“Oh yes,” said my aunt, smiling sweetly, “I get it now.”

“I think,” I said, “it would be interesting someday if Chinese people ate Jewish food as much as Jewish people ate Chinese food. There should be Jewish fast-food places, like the Chinese have. Instead of wonton soup, chicken soup; instead of egg rolls, egg matzo; and a Jewish fortune cookie could be a piece of rugelach with a stock tip or something from a Jewish investment bank. You know, so people could make fortunes.”

My uncle Irwin shot me one of those oysterish glances he specialized in. You know, where the eye is all cold and dead and runny. It wasn’t as fearsome as the lobster look he had given me that morning, but it wasn’t what you would call a tender glance. He didn’t like it when I posited unusual hypothetical situations, like Jewish fast food and fortune cookies. To be honest, he thought I was a bit loony and something of a layabout. One time, he burst into my lair while I was working on my opus, though, actually at that moment, I was playing solitaire at the computer as a way to stimulate the Muse—she often likes it when I play solitaire for an hour or more. But when my uncle saw the cards on the computer screen, he shouted, “So this is what you do in here all the time! Talk to yourself and play solitaire!”

So before things went too far downhill at the Kosher Nosh and became overly frosty because of my Jewish fortune cookie idea, I thought I had better break the news about my leaving.

“I have something to announce,” I said, flourishing my pickle like a green and swollen extra finger. “I’m going to take off for the Poconos for the rest of the summer. I’ve burdened you enough these last few months. But I’ll be in frequent contact and will flood you with postcards of rural landscapes.”

Uncle Irwin, to my surprise, continued to beam oysters at me. I wanted to tell him that oysters were trayf and had no place here at the Kosher Nosh. I had thought he would be glad to hear I was leaving.

In spiritual contrast, my aunt Florence’s eyes were not at all oysterish—they looked sad and concerned. “Alan, I’ve been worried,” she said. “I was going to suggest tonight, after we had our food, something very different from you going off to the Poconos.” She paused, steeled herself, then continued, “I think maybe you should consider going back to rehab.”

“We know you’ve been drinking again,” growled my uncle. “We took you in when you had nowhere to go and the way you thank us is by hitting the bottle.”

This was a contretemps I had not foreseen. I lowered my pickle to my plate, like dropping my sword. Then the Asian family took the empty table next to us. I smiled at them, wanting to welcome them to the promised land of brisket, but this smile was a cover-up while I tried to put together a defense. One came to me: I would drop my shield to go along with my pickle sword. No defense.

“Yes, I’ve been drinking,” I said, taking the honest path, but then, swerving, I continued, “though not to excess. One medicinal glass of red wine each night as a sleeping potion. They say it’s good for your blood. If the French didn’t eat a lot of fat and smoke cigarettes in the delivery rooms of hospitals, they would live exceedingly long lives due to all the red wine they go through.” I hadn’t meant to produce such a disquisition of facts about the state of French health, but when nervous, I’m prone to obfuscation, not to mention lying.

“Alan,” said my aunt, and she looked at me with love, “the Flatleys”—she was referring to the next-door neighbors—“asked us if we were putting wine bottles in their recycling bin. I said no, of course. And then they joked that somebody was going through two or three bottles a night and trying to pin it on them.”

“That’s why you closet yourself in your room all morning, isn’t it?” said my uncle. “You’re hungover! You’re supposed to be writing your book.”

“I do write my book. And I don’t drink at night. It must be Jeeves!”

“Jeeves! You’re insane!” exclaimed my uncle with anger. But he was quite right to be furious with me—I shouldn’t have tried to smudge Jeeves’s character as a way of oiling out of a tough spot.

My aunt ignored this Jeeves exchange. “I spoke to Dr. Montesonti,” she said, and my mind reeled. The dreaded Montesonti—the nerve specialist at Cedars Grove rehab in Long Island where I’d had an unfortunate residence! He had told me that I was a maniac, in the classic sense of the word, which appealed to my ego a little, but he had wanted to destroy my relationship with my Muse by prescribing lithium. “I will not go on lithium!” I had protested. “It’s only a salt,” he’d argued. “I don’t like salt,” I had riposted, and luckily for me he couldn’t force me to take that horrible seasoning. And then I miraculously escaped his clutches when my insurance ran out.

“Montesonti is a terrible doctor,” I said to my aunt and uncle. “What kind of psychiatrist is grossly overweight and chews Nicorette gum?”

Aunt Florence didn’t respond to my statement; she clearly had her speech prepared and pressed on with it:

“He recommended that either you come back to Cedars or we find you a place out here. But he also said that if you refused to go back to rehab, that we were to ask you to leave. That by letting you stay, we were enabling you. That we had to give you tough love. Your mother would want me to love you any way I can, and if the doctor feels that tough love is the best kind, then that’s what we have to do.… Will you go back to rehab? You hardly went to AA, and you haven’t stopped drinking on your own, as you promised. And that was our contract—a quiet place to do your writing if you don’t drink. So either it’s rehab or we can no longer have you in the house.”

I could see that my aunt hated to say this, but she thought she was doing the right thing, and perhaps she was.