Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

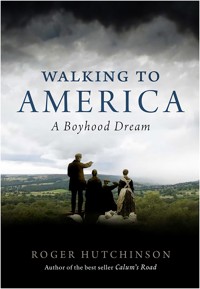

Walking To America follows and recreates the immense journey, in search of a new life and of a miracle doctor who could cure the blindness of one of their number. The journey was taken largely on foot by a small working-class family unit from England in the 1880s, to Liverpool, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, New Orleans, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and back again. Written as travelogue and as a history of one of the great neglected subjects - the New World immigrants who returned home to the Old, Walking to America is a personal tale, full of characterisation and human stories, based upon received lore, followed footsteps and careful historical research.An epic, covering thousands of miles and cultures and environments as diverse as the Victorian UK coalfields, the great imperial entrepot of Liverpool, the post-bellum American south, roaring 1880s New Orleans, the stew of the free-for-all Pittsburgh mines, Texas in the wake of the Alamo, the unclaimed Indian Territory of North America and the ultimate frontier of the Petrified Forest in Arizona - all seen through the eyes of a small group of identifiable and sympathetic, real and ordinary men, women and children from the north-east of England. Walking to America is a great and gripping adventure of discovery, hope and loss. And it is all true.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 305

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Walking to America

This eBook edition published in 2013 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2009 by Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © Roger Hutchinson 2009

The moral right of Roger Hutchinson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-559-8

ISBN 13: 978-1-84158-783-7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

To Rosina, Ina and Rosie

Contents

Maps

Prologue

THE KNOWN

1 Rest-Stops on the Road

Interlude

2 Between the Sea and the Soil

Interlude

3 Tales of Ordinary Freedom

Interlude

4 Sisters

Interlude

5 Hell with the Lid Taken Off

THE UNKNOWN

Interlude

6 The Irish Channel

Interlude

7 Nothing Exists But Mind

Interlude

8 The Painted Desert

Interlude

9 The Petrified Forest

THE KNOWN

Interlude

10 Return Emigrants

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

The North of England, 1883

United States of America and territories, 1885

My father’s father, whose name was William Hutchinson, was 31 years old when his only son was born. That son, my father, whose name was also William Hutchinson, was 35 when his new bride gave birth to me. This is not a riddle – add them up. They amount to the fact that I knew my grandfather, although he died at the good old age of 77, only in the last few years of his life and the first few sentient years of my own.

William Hutchinson was, in the second half of the 1950s, a retired collier. He lived in a small bungalow on the south bank of the River Tyne in north-eastern England. A Victorian by birth and upbringing, he adhered in the middle of the twentieth century to what I now recognise as the minor habits of the nineteenth-century working classes. He broke away the shells of soft-boiled eggs, tipped the white-and-yellow ooze into a bowl and sipped it from a spoon. He poured his morning tea firstly into a cup. He stirred sugar and milk into the cup and then transferred its contents to a deep saucer, held the saucer in both hands and drank the dark brown liquid carefully from the rim.

Those are the wide-eyed memories of the boy that I was when he died. I have few others. But among them is the impression that he seemed entirely housebound. He could walk, but rarely did. Some of his children had motorcars, but he never allowed himself to be taken out for a drive. There was a small front garden by his cottage, and beyond it a threadbare village green, but he never set foot in them. It seemed as though he had transferred, overnight, his working life underground to his retirement indoors, preferring even in the brief freedom of his eighth decade to stay away from the direct light of the day and the hubbub of the busy world on the surface of the earth.

If, unlike everybody else that this child knew, my grandfather never left his house, he did have one intriguing and entirely compensatory asset. Unusually for a man of that class at that time, and doubly unusually for a man who in most other respects seemed to belong to a previous era (he did not own and might have had difficulty operating a telephone), he had a television. As we at home did not, that screen in my grandfather’s cottage was the doorway to wonderland. I am not sure what he – sitting stiffly in his armchair – preferred to watch. Of course, as there were only two channels, the exercise of preference was, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, limited almost to having the TV set turned on or off. But I was entranced by every moving black-and-white image, from the puppet shows to the news bulletins and the glorious Hollywood movies.

So, like my grandfather, I spent my time at his cottage indoors, on the floor beside his armchair, absorbed in the television set as he sat enigmatically silent and still above me.

It was on one such occasion that another of the few episodes which drilled themselves into my memory occurred. An American made-for-television western was showing. I cannot remember which one it was. Wagon Train, perhaps, or Gunsmoke. There arrived a lull in the action, during which the camera panned lovingly down a wooded valley towards a plume of smoke wafting vertically through the still air. The source of that plume of smoke was a small log cabin, set alone in a glade, surrounded by rough timber fencing, studio-recreated in the frontier style.

My grandfather sat forward in his chair. He pointed an index finger at the screen and spoke to me his first words of the evening. (Of the day? Of the week? Of the month?)

‘I used to live there,’ he said.

THE KNOWN

1

Rest-Stops on the Road

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1885

‘For Disappointments, that come not by our own Folly, they are the Tryals or Corrections of Heaven: and it is our own Fault, if they prove not our Advantage.’

– William Penn (1644–1718), founder of the Province of Pennsylvania and the city of Philadelphia.

On a winter morning early in 1885 a young woman looked from the deck of the passenger steamer British Crown upon a new city whose name had haunted her since childhood. Rosina Hutchinson, her husband Miles, her brother-in-law Christopher, her baby son William – whose second birthday had occurred during the voyage from England – and their 139 shipmates were in pursuit of the fantasy of Philadelphia and the fertile interior of the state of Pennsylvania in the United States of America.

Rosina, William, Miles and Christopher Hutchinson were far from being alone. Twenty-seven thousand Europeans had already arrived in Philadelphia in the single year of 1884: about 500 men, women and children made unsteady landfall on the Delaware wharves each week. More than a quarter of the city’s 800,000 population had been born outside the USA. Half of those 200,000 immigrants were Irish, 50,000 of them were German, and of the rest, perhaps 30,000 or 40,000, had travelled from England and Scotland.

Among them were three of Rosina’s sisters, who had preceded her to Pennsylvania a year earlier. Two of them, Sarah and Rachel, had followed their husbands overland to Pittsburgh and the trumpeted employment opportunities of the western Pennsylvania coalfield.

The other sister, Kate, remained on the coast. Kate was blind, and she and her husband, Tom Wilkinson, were still in Philadelphia partly because Tom – a man who had registered his occupation as ‘farmer’ on the emigrant ship – had no immediate desire to resume his British occupation of coalmining, and partly because rich, sophisticated Philadelphia offered remedies for Kate’s sightlessness which were unavailable in proletarian Pittsburgh.

Remarkably, the city and the state could accommodate the horde of immigrants, and most of their reveries. The continent of infinite opportunity was only just beginning properly to exploit itself.

Miles, Rosina, Christopher and William Hutchinson disembarked that winter’s day at the very beginning of 1885 on a wharf at the foot of Philadelphia’s Washington Avenue, to be met by Kate and Tom. The river behind them swarmed with three-masted schooners, two-funnelled steamers, yachts, ferries, and various sea and river-going mongrel hybrids of steam and sail. A small, wooded island with a handful of houses, the tall, smoking chimneys of manufactories and a couple of crumbling windmills stood a few hundred yards offshore. Half a mile beyond Windmill Island, at the opposite, eastern side of the Delaware River, there appeared to be a sparse rural settlement.

The Washington Avenue wharves were surrounded by ‘warehouses, factories, sugar refineries, freight depots and grain elevators, all connected to the vast yards of the Pennsylvania Railroad’. The Hutchinson family entered the upper floor of a two-storey building and passed through a cursory customs inspection which was chiefly designed to confirm that they were neither paupers nor felons.

They then walked downstairs and out into a new world. Before them, as far as the eye could see, the orderly grid of Philadelphia’s terraced streets stretched westward like a chequer-board. Horizontally, its pattern was broken hardly at all. Vertically, it was interrupted by a handful of mammoth civic and commercial towers. New buildings were rising on every corner; the roads rattled with horse-drawn streetcars and carriages and echoed with the abrupt shouts of working men.

Philadelphia coped in a couple of ways with the arrival of 20,000 to 30,000 foreigners on its doorstep every calendar year. Downstairs from the customs office in that two-storey building at Washington Avenue wharves was a railway ticket booth. Those many immigrants who had prearranged jobs elsewhere – as farmworkers, perhaps, or industrial labourers – could walk from the building straight into the Pennsylvania Railroad yard, onto a train and out of Philadelphia.

And as for the others, such as the Hutchinsons – Philadelphia put them to work. Large though the city was, it was not a totally foreign place. English was the default language of most of its citizens. There were unrelated Hutchinsons, the descendants of earlier immigrants from the north of England, scattered about its residential streets and even serving with distinction in its board-rooms. A famous travelling circus managed by Messrs Phineas T. Barnum, James Bailey and James Hutchinson had recently entertained Philadelphia. (James Hutchinson’s share would be bought out for $650,000 by his partners a couple of years later, in 1887, allowing this particular Hutchinson to retire in unimaginable luxury and the show thereafter to tour simply as Barnum and Bailey’s.)

Badly paid employment and basic lodgings were easily found. Philadelphia’s tenements were notorious for their over-crowding – as many as 50 or 60 people sharing a single tenement terraced house, with a family to each room. Thirty or forty years earlier the city’s workers had been among the most militant and revolutionary in America. But when the Hutchinsons arrived a devastating civil war had ended just 20 years earlier. The nation had still not healed itself; and it was engaged more with reconstruction and the benefits, however meagre to most working people, of a Golden Age of commercial expansion. Philadelphia was a calmer place in the 1880s than it had been in the 1840s. And besides, those English immigrants were – and perceived themselves as – birds of passage. America’s industrial disputes were not yet their own. Philadelphia’s filthy tenements were merely rest-stops on their road to a better life.

The Hutchinsons walked out of the riverside complex and into the town. They made their way past elegant colonial-Georgian townhouses and picturesque parks. They walked up broad boulevards lined with chestnut trees and those triumphant totems of white America: 100-foot-high telegraph poles weighted down like grapevines with countless clusters of packed conductor rods. They walked into the city centre through canyons of tall insurance buildings, trust companies, corporate headquarters, banks, hotels, real-estate brokers and savings and investment trusts.

They bought a copy of one of the local newspapers, the Philadelphia Public Ledger, and discovered an astonishing number and variety of situations vacant for both men and women. Philadelphia was in need of cooks and waiters, clerks and painters, laundresses and factory hands, carpenters, dressmakers, barbers, nurses, wallpaper hangers and people willing to earn a basic stipend by caring for other working citizens’ vegetable gardens. Labourers were in demand throughout the city, from the wharves to the sensational edifice and tower of the enormous new City Hall, which had been begun in 1872 and was, like some medieval European cathedral, still in construction 13 years later. Earning a daily dollar in Philadelphia in 1885 would not be a problem. At the end of their first day they felt nervous, exhausted and exhilarated. They were facing a terrifying freedom.

It was of particular significance to the Hutchinsons that the local newspapers also carried large advertisements from gentlemen offering cures for most afflictions. Aware of the bad reputation which had attached to others of his kind, Professor Munyon of Arch Street announced that: ‘There is no punishment too severe … for those who deceive or take advantage of the sick. You may sell a shoddy garment for pure wool, and you only affect a man’s purse, but when you palm off a spurious medicine on a sick person, you may cause months of suffering and possibly the loss of a precious life.’

Professor Munyon’s conscience was clear. ‘In this city alone more than thirty thousand people declare they have been cured by his little sugar pellets. Professor Munyon does not claim that his remedies will cure in every case, but he is prepared to prove that they do cure over 90 per cent of all curable cases where the remedies are taken according to directions.’

Sadly, Professor Munyon specialised chiefly in the cure of rheumatism, asthma, ‘all Female complaints’, kidney troubles, piles, consumption and neuralgia. His little sugar pellets and other pharmacological products were not designed to give sight to the blind.

But others were, and they found a ready market.

The remedies were many and various. Not long after Kate Wilkinson’s arrival in the United States the Philadelphia newspapers would report the case of Thomas T. Hayden. Hayden was a celebrated actor on the north-east coast of America. In 1891 he was inexplicably – and apparently incurably – struck blind. Hayden’s 50-year-old widowed mother consequently moved in to care for her son.

A year later, on the morning of 25 June 1892, Thomas Hayden woke up, got dressed and ‘groped about the house’ calling for his mother. Receiving no reply, he assumed that she had fainted. He got down on his hands and knees and crawled over every floor in the house, including the basement, until he finally discovered her dead of a heart attack before the kitchen stove.

Having buried his mother, Thomas Hayden determined to cure his own blindness. The actor placed himself in the hands of Augustus Theiss, a practitioner who promised to restore Hayden’s vision within 12 months.

Theiss’s treatment was painful and expensive, but plausible. He had synthesised a liquid ‘remedial agent’ which would only work on a patient’s eyesight if it was ‘brought into close contact with the blood vessels’. So he had constructed a large wire brush bristling with 33 sharp steel prongs. Those prongs were placed against some exposed portion of Thomas Hayden’s naked body. Augustus Theiss then ‘by means of a spring, drives them into the flesh for an eighth of an inch or more, leaving 33 distinct punctures’. Theiss’s remedial oil was rubbed into the holes, causing ‘great pain for a few moments’.

After just two sessions with Augustus Theiss, Thomas Hayden was optimistic about regaining his sight despite – or perhaps because of – having been caused great pain. In the first treatment Theiss applied his steel brush to Hayden’s body 421 times, causing around 14,000 punctures. On his second consultation Theiss upped the dose to 22,011 punctures (Hayden was presumably counting each one). With a total of more than 36,000 perforations in his body ‘from head to foot’, Thomas Hayden admitted to having ‘suffered greatly, not so much from the prickings as from the rubbing of the oil into the skin, which is blistered by the operation’. The positive side was that Hayden felt such improved sensations in his body tone that he was confident of regaining his sight. Dr Theiss had assured him that after three months he would be able to ‘distinguish forms’, after six months ‘to recognise friends, while at the end of the year recovery will be practically complete’.*

In fact, in the United States of America Kate Wilkinson and her family were spoiled for choice in their hunt for a cure. The secret of Augustus Theiss’s ‘remedial oil’ may be found in the fact that 20 years earlier, in 1872, news had reached the USA of a German professor who had restored the sight of a blind naval captain by injecting him in the armpit with strychnine. Strychnine being – ‘as is well known’ – a deadly poison, Professor Nagel of Tübingen used only modest quantities, reported the New York Times. But its effect on the myopic ship’s captain was dramatic. ‘On the fourth day of treatment, without help, he succeeded at midday in walking alone through the thorough-fares of the city to the home of his family, a mile from the infirmary.’

A cure for blindness presented obvious obstacles to its salesmen. Blindness was a cut-and-dried, black-and-white condition. A person was either blind or could see. Unlike maladies such as cancer, for which remedies were also enthusiastically advertised, it was difficult to peddle an alcohol-and-morphine-based alleviative for blindness and insist that the consequent short-term relief was the first step towards a full cure. Short-term relief for blindness was as elusive – and as difficult to feign – as a full cure. Most ‘scientific’ practitioners like Augustus Theiss therefore played a long game, warning that their remedies would take effect only gradually, over an unpredictable but extended period of months and years, so long as the patient continued to pay for the treatment.

There were, of course, exceptions. William Williams was imprisoned in Atlanta, Georgia, for swindling $2.50 from a blind man named Robert Ward. Williams had offered to cure Ward’s blindness, on receipt of the $2.50, by hammering an iron tack into the back of his skull. Following the operation Ward remained blind and reported the fact to the Atlanta Police Department. The tack had not affected him much and had been removed, but the swindle, said Robert Ward, ‘hurt considerable’.

Kate Wilkinson was no more likely to submit to iron tack treatment than she was prepared to rub the relics of saints on her sightless eyes. She and her family had not travelled to the United States of America in search of the superstition and witch’s brews which were plentiful back in Europe, but to discover the latest advances of nineteenth-century medical science. They had come specifically for the magneticon and other branches of electro-therapy.

Cutting-edge nineteenth-century medical treatment did not come cheap. The $2.50 which William Williams received from Robert Ward for driving a nail into his head was on the lowest rung of surgical fees, and $2.50 was not an insignificant sum. While Tom Wilkinson and Miles Hutchinson had no difficulty finding work in Philadelphia, they were unlikely to become wealthy. Their unskilled labouring jobs paid them around $12 a week. Christopher Hutchinson, who had travelled west to join the other men in Pittsburgh, was already earning more money in the coalfield. Casual home-based piecework sewing or knitting would have allowed Rosina and Kate to add a few extra dollars to the communal funds. But their weekly rental of just two barely furnished rooms cost no less than $3 a week. Fuel had to be bought, and although food was plentiful and cheap, it still had to be paid for. The streets of Philadelphia were paved with nickel, not gold.

Electro-therapy, magnetism or mesmerism had been gathering credibility as a panacea for half a century in the United States before Kate Wilkinson and her extended family arrived. It was rooted in the belief that the human body was essentially vitalised by ‘animal electricity’. If a part of that body malfunctioned, therefore, an artfully applied electrical current was the logical way to correct it. There were ‘electro-vital forces’ in the human physique, argued the qualified Chicagoan physician E. J. Fraser in 1863, which could be ‘augmented or diminished at pleasure, by the application of artificial electricity’.

By the 1880s, commercial companies were marketing the battery-powered machines to apply that electricity to patients. A practitioner would stump up $25 for the battery, $10–$18 for the appliance and as much as $100 for an internal surgery galvano-cauteriser. Manuals came with the equipment. They said that the shocks imparted to patients by electro-therapeutics could stimulate digestion, calm nerves, remove moles, ulcers and tumours, correct sexual dysfunction … and restore eyesight.

No licence or qualifications were required by electro-therapists in the 1880s. Later in the century the American Graduated Nurses’ Protective Association would campaign for federal legislation to ensure ‘that no person shall practice electro-therapy, hydrotherapy or mechanico-therapy without holding a duly registered license as a trained nurse’, but until then it was an open shop. And in the meantime, according to one authority, the efforts of qualified physicians ‘to compete with irregular electrotherapists were actually counterproductive. By offering the technique in their own practices, they legitimised portable electric health machines that could easily be purchased by unlicensed practitioners …’

A stranger in a strange land, Kate Wilkinson would have put herself in the hands of a competent or a charlatan without knowing the difference. In fact, there was not much difference. In the United States in the 1880s qualified graduates of medical schools and unqualified miracle healers shared several identical debts to electro-therapy, the chief one being to recoup their $140 investment in the equipment.

That imperative resulted in medical charges – even in such a competitive environment as Philadelphia, which was pullulating with physicians – that the Wilkinsons and the Hutchinsons could not easily afford. Casual labouring in Philadelphia offered them no great prospects. The booming coalmining industry of western Pennsylvania, whose output would in just a few years outstrip even that of the Tyne and Wear field, offered both progress and regress.

It would be a step forward – possibly a large step forward – in potential financial reward. It would be a step backwards into the dark and dangerous world that the men had left behind in Britain. And although they did not know it, it would take them into the arenas of industrial disputes more violent and bitter than any which echoed around the collieries back home at Billy Row and Cornsay.

But they went. After those frustrating weeks of getting by and making do in Philadelphia, a consensus was reached. They would pack their things once more and travel to join their relatives in Pittsburgh.

* Thomas Hayden never did recover his sight. His acting career blighted, he nonetheless made himself available for recitations from memory at public events for the rest of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, and took comfort – like many other performers of his time – from being a member of the fraternity named the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks.

I never went down a mine. British coalminers, and probably coalminers everywhere else, had a mildly schizophrenic attitude to their vocation. Defensive of it to the very last, proud of the solidarity of their comrades and the integrity of their communities, determined in the dignity of their calling, graciously receptive of their unrequested roles as both the commanding officers and the frontline troops of the working classes – most coalminers would nevertheless move as much earth aboveground as they ever did below to try to ensure that their sons did not have to follow them into the pit-cage.

Most failed, of course. During the hundred-year heyday of the British coal industry, between the middle of the nineteenth and the middle of the twentieth centuries, coalmining was as much a hereditary activity as was marquetry or membership of the House of Lords. Only a few got out. My father, William Hutchinson’s youngest child and only son, was one of them. The scholarship which he won to grammar school broke one small circle and unlocked the gate of the cage for his children and theirs. The great majority of his fellow twentieth-century British miners’ sons had the gate slammed in their faces 50 years later. Theirs was the humiliation of leaving the darkest of industrial jobs not on their own terms, but because after the sacrifice of generations and the supposedly unqualified esteem of their fellow citizens, they were considered to be unprofitable.

Then, in the 1980s and 1990s, coalminers and the sons of coalminers began to move. But fallacies about the geographical and social stasis of the earlier, Victorian British lower classes have become established. Received wisdoms have suggested that before the dynamic late-twentieth-century men and women – particularly impoverished men and women – lived a tribal life, were born and bred, married and died within the same fixed community.

Many did, and many still do. In 2008 no fewer than one third of all Britons were still living within five miles of their birthplace. The fraction of stabilised citizens could have been greater in the nineteenth century, even during the upheavals of the industrial revolution and the epochal exodus from the countryside to the cities and the manufacturing towns.

But what evidence we have suggests that it was not much greater, that the British working class was even then vastly more socially and geographically adventurous than our Christmas card images – and preferred folk memories – of timeless, frozen hamlets imply.

Jason Long of Colby College in Massachusetts has spent the days and weeks in dusty archives necessary to establish the precise statistics of Victorian British class mobility; to answering the question, did they stay or did they go? Professor Long concludes that they went – ‘the British populace of the nineteenth century was highly mobile … Nineteenth-century Britain saw both high rates of internal mobility and overseas emigration’.

In the 30 years between 1851 and 1881, fully one quarter of Britons moved from one county to another. During the same period more than half of them changed their town or village of residence. That is not quite the twenty-first-century total of a transitory two thirds of the citizenry, but it is not very far away. It is recognisably close.

In my own adult life I have lived in six postal codes 600 miles apart. Compared to Miles and Rosina Hutchinson, my Victorian great-grandparents, I am a couch potato. In their 20s and 30s they lived in at least eight different places. Four thousand miles lay between the easternmost and the furthest west of their homes. Our journeys have been neither fully representative nor wholly exceptional of our classes and our centuries. That’s the way that people were and people are – different.

2

Between the Sea and the Soil

Philadelphia, County Durham, 1821

‘If ony, then, of Blacky’s race

Ha’e harder cairds than words te play,

Wey then, poor dogs, ower hard’s their case,

And truth’s in what wor preachers say.’

– Thomas Wilson, ‘The Pitman’s Pay’ (1843)

For the best and most obvious of reasons, there have never been photographs of Philadelphia in 1821 – just as none survive of Elizabeth, Rosina’s mother, who was born there in that year. But from sketches and memories and contemporary written descriptions, we can piece together an image of the place.

Compared with what it was to become, Philadelphia in 1821 was rural, tranquil and small. To its east lay the open sea. To its north, south and west a pretty countryside of streams and rivers, cultivated fields and grazing meadows rubbed up against virgin woodland. Philadelphia sat at first slightly uneasily in those surroundings. It was not an ancient, organic parish of wattle and thatch. Philadelphia was a new town of stone, brick and slate. It was a planned model settlement. It had been created, and christened, in broken Greek, ‘the Place of Brotherly Love’ by its optimistic English founder, in the hope that its name could thereafter influence its character.

Its people, when Elizabeth was young, had a variety of early-nineteenth-century occupations. They were blacksmiths, stone-masons, wheelwrights, mill workers and schoolmistresses. They were publicans, glass-makers and agricultural labourers. They were shopkeepers, servants, nightwatchmen and joiners. As Elizabeth grew into a young woman and the nineteenth century picked up speed, some Philadelphians were even employed as railway engineers.

But mostly, by a huge majority, the men were coalminers, the women were the daughters, wives and mothers of coalminers, and the children of Philadelphia were to be what their parents had been. Philadelphia was a colliery village in the north-eastern corner of England, five miles south-west of the port of Sunderland in County Durham. Elizabeth herself would never see the other, larger, more widely celebrated Philadelphia, at the far side of the North Atlantic Ocean. But four of her children would.

Elizabeth’s Philadelphia was built on top of what was known, after its great rivers, as the Tyne and Wear coalfield. This vast resource would remain for two further centuries one of the biggest exploited deposits of coal in Europe. Coal had been harvested from the sea and the land in these parts for perhaps two millennia before the 1690s and 1700s, when Lord Scarborough decided to exploit this particular seam commercially.

By 1727 Scarborough had three underground pits operating in the earth below what was to become Philadelphia. Seven years later, in 1734, he sold his increasingly profitable lease to a partnership dominated by the wealthy Sunderland entrepreneur John Nesham. In 1774 Nesham sank a large and ambitious shaft from the surface to the main coal seam five miles south-west of Sunderland, in the central, Durham section of the field. The usual shacks, shelters, shanties, workshops and eventually rows of residential cottages grew up around this venture. Rather than let his colony on the industrial frontier adopt a second-hand name, John Nesham christened it himself. He called it Philadelphia. Nesham had a fondness for American references. Two years later he christened another Durham colliery Bunker Hill, after the bloody American War of Independence battle in 1775.

When Elizabeth was born in Philadelphia in 1821 it was a compact, dedicated colliery village. Nesham had sunk more pits on the same site, which he called after his daughters. Generations of nineteenth-and twentieth-century Philadelphia miners, including Elizabeth’s father, would know the Dorothea and Elizabeth pits in a familiar diminutive, as the Dolly and the Betty. In the first decades of the nineteenth century there was living in Philadelphia a disproportionate number of girls and young women named Elizabeth and Dorothy. The possibility is not to be discounted that Elizabeth’s collier father christened his own eldest daughter after the pit shaft down which he worked.

Elizabeth was raised in a placid, bucolic environment. The dirt and squalor of coal-mining districts was mostly, by definition, beneath the surface of the earth. Her father walked each day through coppices and green fields to a nearby pithead and laboured underground for ten or twelve hours each twenty-four, on a fore-shift (night-time until late morning) or a back-shift (morning until evening), every day of the week but the Sabbath, to earn the money to keep his family alive. The effect on his health and appearance of his long career underground – allied with an impoverished diet – was sadly apparent. The early-nineteenth-century pitman was described by a sympathetic witness as ‘being diminutive in stature, misshapen and disproportionate in figure, with bowed legs and protruding chest. His features were equally unprepossessing, hollow cheeks, over-hanging brow, forehead low and retreating.’

His average life expectancy at birth was not much more than 30 years. The national British working class average life expectancy in the first half of the nineteenth century was not significantly older. Coalminers fell just short of the mean, due to lung and respiratory diseases, crippling individual accidents and pit disasters. The latter were frequent and savage.

But if the pitman’s life was often short, it would be wrong to dismiss it as unrelievedly nasty and brutal. Thomas Wilson was born on the Durham bank of the River Tyne in 1773. He worked in coal mines as a boy, but in his leisure hours he studied. In his 20s, instead of hewing at the coal-face, he became a schoolteacher. In his 30s he became a partner in a profitable Tyneside business. A prodigious autodidact and early exemplar of the miner’s urge for self-improvement, Wilson devoted much of his adult life to literature. In the late 1820s he wrote and published an epic dialect poem titled ‘The Pitman’s Pay’. Nominally about the activities of north-eastern miners on their fortnightly pay-nights, ‘The Pitman’s Pay’ provides a sharp first-hand insight into the extramural activities of the early-nineteenth-century Durham miner.

It is faintly Hogarthian. There is no doubt that – on at least this one Saturday night every fourteen days – many if not most male miners got drunk and gambled. Some, although apparently a small minority even in the late-Georgian and Regency years, were devoted to betting ‘On cock-fight, dog-fight, cuddy-race, / Or pitch-and-toss, trippet-and-coit …’. But following the first few pints, according to Wilson, the loosened tongues of the Saturday night majority would discuss much more than ‘their wives and wark’. Wide-ranging debates around the inn tables would cover ‘The famous feats done in their youth, / At bowling, ball, and clubby-shaw – / Camp-meetings, Ranters, Gospel-truth, / Religion, politics, and law.’

‘Religion, politics, and law …’ These men and women were far from being stupid or incurious, unambitious or disorganised people. As early as 1831 a Durham miner named Thomas Hepburn, who had worked underground since the age of eight, established the first Northern Union of Pitmen. This seminal association immediately attracted tens of thousands of Tyne and Wear miners to strike meetings, and a two-month walk-out achieved some concessions in hours and working conditions.

The clash of articulated opinions on a variety of elevated subjects hums down from those precious, lubricated Saturday nights of leisure. ‘We need not wonder at the clatter, / When ev’ry tongue wags – wrong or right.’

If that was the life of Elizabeth’s father, and the life of her other male relatives, Elizabeth herself was fortunate not to share it. The employment in underground pits of women (and boys under the age of ten) was not outlawed until the passage in 1842, when she was 21 years old, of the Mines and Collieries Act. In fact, most women in the mining communities of the Durham coalfield had not worked underground since the 1780s. Their husbands and fathers and, it must be presumed, several of the coalowners preferred them when possible to lead a domestic life above ground – a discrimination which was approved by almost all of the women themselves.

At the age of 21, Elizabeth escaped into marriage. Naturally, she married a coalminer. William Robson had been born a year before Elizabeth, in the parish of Washington, another County Durham pit-village nomenclaturally twinned with the United States of America. Washington stood ten miles west of Sunderland and five miles north of Philadelphia. In his teens William had moved with his father and mother a short distance south to live at Shiney Row in the northern outskirts of Philadelphia. Upon the 22-year-old William’s marriage to the 21-year-old Elizabeth in 1842, he was working in the Success pit at Philadelphia, and William and Elizabeth set up home in what was then the Success Row of colliers’ cottages.

This couple’s marriage would endure for more than 50 years: an almost miraculous span for an industrial working-class partnership in the nineteenth century. It would also produce 11 children who survived into and beyond infancy. The youngest of the daughters was christened Rosina.

In her first five years of wedlock Elizabeth gave birth to three girls, one of whom was named after her. They were followed in 1850 by the senior boy, who took his father’s name of William. William was pursued into and out of the family cradle between 1852 and 1864 by five more daughters. In 1864 and 1866 – when she was 43 and 45 years old – Elizabeth Robson’s last two children were boys.

The eleven infants were born in five different places. As a hewer at the coal-face William Robson hawked his trade from pit to pit. Over 200 new coalmines were sunk in County Durham during the nineteenth century, so there was ample choice. The number of Durham mineworkers rose from 34,000 to 153,000 between 1844 and 1900. There was clearly work to be found – but even in this employee’s market, between the smashing of Thomas Hepburn’s Northern Union of Pitmen shortly after the 1831 strike and the growth of the Durham Miners’ Union in the 1870s, it was work under the coal-owners’ conditions.