Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

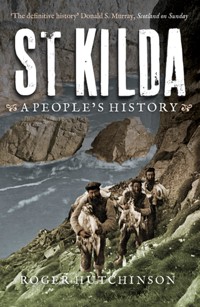

St Kilda is the most romantic and most romanticised group of islands in Europe. Soaring out of the North Atlantic Ocean like Atlantis come back to life, the islands have captured the imagination of the outside world for hundreds of years. Their inhabitants, Scottish Gaels who lived off the land, the sea and by birdcatching on high and precipitous cliffs, were long considered to be the Noble Savages of the British Isles, living in a state of natural grace. St Kilda: A People's History explores and portrays the life of the St Kildans from the Stone Age to 1930, when the remaining 36 islanderswere evacuated to the Scottish mainland. Bestselling author Roger Hutchinson digs deep into the archives to paint a vivid picture of the life and death, work and play of a small, proud and self-sufficient people in the first modern book to chart the history of the most remote islands in Britain.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 678

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

St Kilda

A PEOPLE’S HISTORY

First published in 2014 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House 10 Newington Road EdinburghEH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Roger Hutchinson 2014

The moral right of Roger Hutchinson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 219 1 eISBN: 978 0 85790 831 5

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore Printed and bound by Gutenberg Press, Malta

To Caroline

Always take the turning

Contents

List of Illustrations

Map

Foreword

1Rachel’s Unhappy Adventure in England2Amazon Queens, Norsemen and Gaels3The Saint Who Never Was4False Prophets and Ministers5The Whole Island Dancing6From Thatch to Zinc7The First Exodus8Speaking Truth to Power9The Royal Wedding10An Indian SummerAfterwordNotes

Index

List of Illustrations

Black-and-white plates

Early 19th-century sketches of the old, crowded clachan in Village Bay, before it was dismantled and replaced by the row of crofthouses on Main Street.

A Victorian imagination of Tigh an Stallair on Borerary.

‘Being lowered on a homemade rope down the dizzying cliffs of Conachair required a superhuman quantity of courage.’

‘Mid 19th-century St Kildan children, tow-haired and bright-eyed.’

Euphemia ‘Effy’ MacCrimmon: the last of the old St Kildan tradition-bearers, late in the 19th century.

Mother and child during St Kilda’s short Indian summer.

A group of St Kildans in 1884, with temporary schoolmaster Kenneth Campbell.

Ann Ferguson, the media’s ‘Queen of St Kilda’, on the eve of her intended marriage.

Ann’s betrothed, Iain ‘Ban’ Gillies, before the show wedding was called off in 1890.

The widowed Ann Gillies awaits evacuation from Village Bay.

The celebrated ‘St Kilda Parliament’, posed in suitable dignity in 1885.

A more relaxed photograph of the ‘parliament’ in the 20th century.

Finlay MacQueen in intense discussion with the MacLeod Estate factor, John MacKenzie, in 1896.

Neil Ferguson with a sack of feathers on his back.

A group of late 19th-century women and girls display tweed wares for sale on Main Street.

A medium-sized cleit while still in use.

The women span and the men wove their tweed. An outside demonstration of what most usually would have been an indoor activity.

The factor’s house damaged by shellfire from the German U-90 in 1918.

Number One Main Street: another casualty of the German submarine’s bombardment.

The 25-pound gun which was emplaced beneath Oiseval following the German attack.

Collecting seafowl from the cliffs beyond Village Bay.

Colour plates

Boreray and Stac Lee seen from Conachair cliffs on Hirta.

The entrance to the souterrain Tigh an t-Slithiche in Village Bay.

The massive stone animal enclosures in the basin of An Lag on Hirta.

Dun as seen from an abandoned house in Main Street.

A medieval cross inscribed on a rock, deployed much later as a window frame at Number 16 Main Street.

The interior of a cleit.

The cleits, croft walls and roofs of Village Bay.

Cleits within and without the great dyke, and the remaining foundations of an older house.

A modern cruise ship anchors in the shelter of Dun in Village Bay.

The St Kilda archipelago

Foreword

‘So much has already been written about St Kilda,’ wrote Norman Heathcote in 1900 at the beginning of his book St Kilda, ‘that I suppose I should apologise for adding yet another book on the subject, but I believe a good many people take an interest in the little island, the most remote corner of the British Isles, and … I venture to hope that my book may not be de trop.’

I know how he felt. The author of any new book about St Kilda is not standing on the shoulders of many giants. But he or she is perched perilously at the apex of an enormous human pyramid of predecessors. Since Heathcote wrote those lines more than a century ago several hundred books on aspects of the St Kilda islands have been published and republished. They have issued in such a flood that, in my occasional capacity as a book reviewer, I once threw up my hands and cried in print, ‘Enough!’

Then I went there. It is difficult for a writer to spend any amount of time in St Kilda without being driven to write about the place. When that writer has spent an adult lifetime living in and writing about the north-west Highlands and Islands of Scotland, the urge is irresistible. All of the Hebridean islands are unique – all of the European islands are unique. St Kilda is simply the most unique of them all.

It is also, and has been for centuries, the most misinterpreted and misrepresented of island communities. For over 300 years, from the late seventeenth to the early twentieth century, St Kilda’s apparent alienation from the rest of Europe tempted writers, even writers who understood both Gaelic and other Hebridean settlements and who should have known better, to impose upon it a popular idealisation.

The people who lived on Hirta moved, through no volition of their own, from being noble savages in the Age of Discovery to utopians and perfect communists and anarchists in the time of Marx and Bakunin, while simultaneously supposedly operating within an established Victorian hierarchy of a local male parliament and an insular constitutional monarchy.

The fallacy at the core of all such projections was that the inhabitants of those distant islands had somehow experienced a form of parallel evolution, uninfluenced in important social and political matters by the rest of Western civilisation. They were the reassuring antithesis of Lord of the Flies. They were an established gerontocracy abiding by ancient behavioural codes. They pulled off the unlikely but flattering trick of proving that, in at least one small set of circumstances, humanity was capable of perfecting the same philosophies and institutions which had evolved on the British and European mainland. The St Kildans were therefore both foreign and familiar.

St Kilda was unique not because its people were uninfected by outsiders – they were persistently infected, both literally and figuratively – but because their lives absorbed and adapted to powerful external influences while remaining, necessarily, more or less the same. It was an intriguingly different way of life but it was not mysterious. A means of surviving – and even thriving – on those unpromising outcrops of land which had almost certainly evolved in antiquity remained unchanged until the second half of the nineteenth century, and its remnants could be observed and identified in the twentieth century.

Since the departure of its last native residents in 1930, the ghost town of Main Street in Village Bay has been an empty space. Historical literature abhors a vacuum. That is the reason for the hundreds of volumes published in the last eighty years, which have clarified, muddied or left undisturbed the water in Village Bay.

Many if not most of those books have been excellent specialist studies. Few of the general histories of the islands, however, have managed to escape what the academic Fraser MacDonald describes as an ‘erroneous narrative [which] ascribes an Edenic character to the St Kildans but implicitly blames them for having material aspirations’. That narrative was not, as MacDonald makes clear, restricted to St Kilda. It has been a common interpretation of the Highlands and Islands which merely found its most perfect subject in the most isolated and distant of the Hebrides – ‘that mountain in the sea’.

St Kilda therefore became and remained the apogee of the sublime, the harsh, beautiful and innocent Highlands. That definition remains alive and active in the twenty-first century, as any Scottish tourism advertising campaign is likely to reveal. It has lost little of its power in four centuries of constant application.

There are numerous problems with sublime St Kilda, the most disturbing of which is that it denies St Kildans throughout history much agency in their own affairs. An unusually hardy, proud and articulate group of feudal vassals – ‘the most knowingest people’ in the words of a nineteenth-century labourer from the east coast of Scotland – have been reduced to cyphers.

This reduction has found its most outstandingly erroneous expression in accounts of the reasons for and handling of the evacuation in 1930. That was a momentous event in which the conduct of outside parties, most notably the British government through its Scottish Office, were models of sensitivity. But in the orthodox late twentieth-century interpretation, the St Kildans were buffeted into helplessness and then were led by their noses from the sublimity of Hirta to the mundanity of Argyllshire by politicians, civil servants, the medical profession and – most absurdly of all – their own Church. The false logic was straightforward. Having achieved a state of sublimity, nobody would voluntarily surrender it. They therefore must have been coerced.

Nobody benefits from such misrepresentation, least of all the St Kildans themselves. I hope that my presentation of an alternative version of their extraordinary history is not de trop.

I have learned about St Kilda from a great many people over the last four decades. There is a complete bibliography at the end of this book, but I must express particular gratitude to the authors Mary Harman and Michael Robson, both of whose forensically researched volumes have offered the comforting shoulder of hard and dependable fact. In St Kilda the hospitality and expertise of Susan Bain, Paul Sharman, Andrew Walsh, Kevin Grant and Dennis Fife did justice to the tradition of their surroundings. Angus Campbell, Christopher Gunn and the crew at Kilda Cruises got me there and back quickly and cheerfully. And for reasons that they will understand, thanks to Torcuil Crichton, Deborah Moffatt, Bill Lawson and John Murdo Morrison. I gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Authors’ Foundation and the K Blundell Trust in helping me to complete this book.

The publishers Birlinn – Hugh, Andrew, Jan, all of you – thanks again. My editor Helen Bleck once again rescued a manuscript from incoherence. Stan, never change.

ONE

Rachel’s Unhappy Adventure in England

ONE SUNDAY IN the spring of 1907 a government Fisheries Protection cruiser working out of Glasgow spotted a steam trawler netting in Village Bay, off the island of Hirta in the archipelago of St Kilda.

The trawler was from Fleetwood in Lancashire and was on a routine expedition to cast her nets on the North Atlantic Shelf 400 miles from home. On that Sunday she happened to be inside the official one-mile St Kildan limit which was designed to safeguard the marine assets of the islanders.

The cruiser bore down on the trawler and arrested her. When both vessels were anchored together in Village Bay some of the cruiser’s officers went ashore. Instead of a grateful St Kildan welcome, they ‘were met by a number of indignant natives, who questioned the right of the warship to arrest a friendly trawler’. The ‘natives’ were led by their young United Free Church of Scotland missionary Peter MacLachlan, who ‘loudly complained of the heinous offence of arresting a steamer on the Sabbath’. (‘The islanders,’ observed the Manchester Guardian, ‘evidently regarded this action as much worse than illegal fishing, which apparently had their blessing.’)

MacLachlan then attempted to revoke the arrest of the Fleetwood vessel. He mustered a boatload of St Kildans who, in a gesture of solidarity and an attempt to stay the hand of the cruiser’s captain, rowed out into the bay and boarded the trawler. It was to no avail. Peter MacLachlan and some other islanders were still on the arrested ship when it was put under tow by the Fisheries Protection cruiser and taken to Stornoway on the island of Lewis, where its captain was fined £90 and from where the St Kildans made their slow passage back home. ‘The crew of the trawler, it is understood,’ said the Guardian, ‘had ingratiated themselves with the islanders by carrying their mails to and from the mainland and performing other friendly services.’

In the early decades of the twentieth century trawlermen from Fleetwood had a working relationship with the people of St Kilda. The Fleetwood trawler fleet was then the largest on the west coast of the United Kingdom. Since the 1890s its steam-powered boats (which were first introduced to the port by the Marr family of Dundee) had been sailing to the plentiful hake and dogfish grounds off the west of Ireland, off the Faroes, off Iceland, to Bear Island south of Spitzbergen and to the relatively homely north-west of Scotland, particularly the waters around Rockall and St Kilda.

The steam trawlermen spent weeks and often months at sea in brutal conditions. St Kilda was the most isolated human settlement in the British Isles. The islands lay 40 miles from the most westerly point of the Outer Hebrides and 100 miles from the Scottish mainland. On most days they were as invisible from any other part of Europe as a ship in mid-ocean. Their inhabitants led a subsistence lifestyle supported by an irregular commercial steamer service. Fishing boats were frequently the only vessels to approach St Kilda for months on end. A symbiotic connection developed. It started with trawlermen anchoring in Village Bay and putting ashore to pick up fresh water, enjoy tea and company and leave behind tobacco and other small luxuries. It grew into friendship and a form of inter-dependency. As they came to know the islanders and understand their needs, Fleetwood steam trawlers made a point of carrying sacks of meal and bottles of whisky as well as tobacco on their voyages north, and carrying news of the islanders’ circumstances back to the British mainland. In return they were guaranteed a safe haven and a cheerful welcome in the hostile North Atlantic Ocean.

In 1906 this arrangement was officially recognised and formalised when the Fleetwood post office was given responsibility for delivering the mail to St Kilda in its local trawler fleet – a function which had previously lain with the post office at Aberdeen on the far eastern coast of Scotland.

In the summer of 1924 another steam trawler from Fleetwood in Lancashire answered a radio signal for assistance from St Kilda. The ST Philip Godby put into Village Bay and picked up an elderly crofter and weaver named Finlay MacQueen who required medical treatment for a growth on his shoulder. When the trawler returned to Fleetwood it carried Finlay MacQueen in steerage. The 62-year-old widower spoke very little English, but a doctor with a smattering of Scottish Gaelic was found in Lancashire and an operation was carried out successfully. The morning after the operation Finlay MacQueen left Fleetwood on another trawler to return to St Kilda. He would, he told his interpreter, ‘never leave St Kilda again’.

Four years after Finlay MacQueen’s expedition for medical treatment from St Kilda to Fleetwood, three other islanders followed him on the same route. In April 1928 the fishing steamer Loughrigg carried to Lancashire a fifty-seven year-old unmarried St Kildan man called John MacDonald, a seventeen year-old girl named Rachel Ann Gillies, who had never previously left the island, and – at least in part as chaperone to Miss Gillies – Mrs MacLeod, the wife of the St Kilda missionary John MacLeod. None of the three had Finlay MacQueen’s linguistic difficulties. Both John MacDonald and Rachel Gillies spoke English as well as Gaelic, and Mrs MacLeod was a native of Gloucestershire. (The English west country accent of the minister’s wife must have contributed to the ‘consternation’ caused when she bustled into Fleetwood post office to pick up the St Kilda mail. ‘They thought I was someone escaped,’ laughed Mrs MacLeod, ‘but I assured them I was quite tame.’)

The arrival on the north-west coast of England of a teenaged girl from those fabled rocks caused even more of a stir. The captain of the Loughrigg, Reginald Carter, accommodated the three St Kildans at his Fleetwood home. They travelled from Carter’s trawler to his house by taxi-cab, ‘and the ride amazed Miss Gillies. Her drive through Fleetwood filled her with wonderment, though she was too excited to express herself ’. This was, the newspapers pointed out, a girl who had never seen a horse, a cinema picture, a motor-car or a train. John MacDonald, who was in ill health and like Finlay MacQueen before him would require medical attention in Fleetwood, was less constrained. He told a reporter that most of the forty remaining St Kildans ‘would leave the island if they had the opportunity of homes and work on the mainland’.

Within three months John MacDonald had returned to St Kilda. Rachel Gillies held out for slightly longer. She found a job in the town and appeared to settle in Lancashire. At the end of April an enterprising journalist took her to the cinema. The feature was an American silent movie starring Joan Crawford and titled The Understanding Heart. (‘Monica Dale is a fire lookout in love with Forest Ranger Tony Garland’, according to an online cinema datebase. ‘Escaped killer Bob Mason hides out in Monica’s observatory and falls in love with her. A fire encircles them and is put out by rain. Bob finally gives her up to Tony and is cleared of his earlier crime.’)

When the film began to roll, reported the journalist, Rachel Gillies ‘sat transfixed. Her facial expression was a study of wonder and fear. Gradually she settled down and rarely took her eyes off the screen … The film puzzled her as representing something different from what she imagined civilisation to be.’ Rachel was obligingly grateful for the experience. ‘We have heard about kinema pictures at St Kilda,’ she said, ‘but we never thought they were so wonderful. It is very wonderful. I never knew there were such things.’

In July Rachel Ann Gillies gave up her job and went back to St Kilda. ‘She soon learned to dislike the hurried life of England, and after the first few weeks of excitement the novelty of things wore off and she longed for the solitary life at St Kilda, where the people during the winter are cut off from the outer world, save for the occasional visits of Fleetwood steam trawlers. She kept wanting to know how [her widowed] mother would be going to gather the peat for the winter’.

‘When she left she discarded modern dress and went off in homely tweed, woven by her fellow-islanders. She returned to St Kilda with a feeling of pleasure at having finished with the hectic conditions of life on the mainland, and resolved never again to forsake the quiet of her home.’ She was too polite to remark to the reporters that while until four months ago she may not have seen a moving picture, a motor-car or a train, they had never seen the sun set behind Mullach Mor, its last rays light up the black rocks of Dun and the evening draw down like a veil across Village Bay.

Two years later, in August 1930, Finlay MacQueen, Rachel Ann Gillies and John MacDonald would be among the last three dozen St Kildans who were evacuated from their island and offered new homes and jobs on the Scottish mainland. They sailed out of Village Bay on the Admiralty cruiser HMSHarebell with Rachel’s forty-one year-old mother Ann, her eleven year-old younger sister Flora and another thirty of their relatives and neighbours.

It was not quite the first time in 4,000 years that the islands had been left uninhabited by humans. But it was the first time in 4,000 years that the islands had been considered uninhabitable. ‘It was really quite sad,’ Flora Gillies would recall, ‘to see the chimneys and knowing we would never be back again.’

Four hundred miles away there was sympathy with Finlay MacQueen’s reluctance to leave. It was reported that,

The deep-sea fishermen of Fleetwood contemplate the evacuation of the small population of the lonely island of St Kilda, in the Outer Hebrides, with mingled feelings …

In the gales that sweep across the west Scottish fishing areas almost continuously from December to March, St Kilda forms a harbour of refuge, and virtually every Fleetwood trawler has at some time or other run into Parson’s Bay – a locality not indicated on any chart, but known to the deep-sea fishermen who so christened it because the house of the island’s parson lay near the beach. The fishermen do not like to think that in the coming winter the island will be a scene of desolation and that the lights will no longer be a cheerful beacon to them during the winter storms.

St Kilda without the natives is a disagreeable prospect in the eyes of every deep-sea fisherman.

As many of the older St Kildans would have known, they were not the first twentieth-century Hebridean Gaels to desert their native islands, and as some of them may have suspected, they would not be the last. Following the ravages of the nineteenth century, it was either the implicit or explicit policy of every twentieth-century British government to repopulate the north-west Highlands and Islands. They found the task more difficult to achieve than to pledge. The number of abandoned islands grew in every passing decade.

Between 1906 and 1912 the inhabitants of Pabbay and Mingulay, two islands at the foot of the Outer Hebridean chain 90 miles south-east of St Kilda, departed for lives in other places. At 2½ square miles, Mingulay is almost exactly the same size as Hirta, St Kilda’s main island, and in 1881 it had supported 150 people, almost double the Hirtan population. By 1912 they had all left.

In 1920 the last few families deserted Eilean Mor in the Crowlin Islands between Skye and Applecross. In 1921 there were ninety-eight people living on Rona, an island off the north coast of Raasay which also lay between Skye and the Scottish mainland. By 1930 all but the Rona lighthouse keepers had departed. In the same decade the few people who had clung to the land on Ronay, an island off the east coast of North Uist which 100 years earlier had had a population of 180, gave up their unequal struggle.

In 1934 the twenty people of Sandray, another southern Hebridean islet, left for good. In 1943 Heisker – an island with curious historical links to St Kilda – was emptied. At regular intervals thereafter the fires were put out and the Gaelic bibles left open in empty homes on Soay, Scarp, Taransay, Boreray and Vallay.

They were all, like St Kilda, ‘voluntary’ evacuations, in the sense that a majority of the departing population considered life to be unsupportable without such twentieth-century services and amenities as electricity, access to hospitals, tapwater and telephones, and had either petitioned the authorities to be relocated or had simply put their furniture into skiffs and sailed away.

As well as electricity, the twentieth century brought motorised transport and a steadily improving network of roads to the mainland. The Hebrides were first settled and populated during the centuries when travel by water, particularly travel on the open sea, was hazardous but also faster, less arduous and therefore more popular than travel by land, especially in the mountainous Scottish Highlands. Long before and long after the Middle Ages, a clachan huddled at the end of a glen in Lochaber or Assynt was likely to be more remote and inaccessible than any insular community. The twentieth-century trawler fleets were St Kilda’s last reminder of those happier days.

When it came to the moment of departure, St Kilda was typical of all the deserted islands in at least one obvious respect: the older folk regretted it most. Sorrow followed a comprehensible sliding scale. The children, such as Flora Gillies, were leaving only their infancies behind. The younger adults, such as Rachel Gillies, could insulate themselves against the rueful chill with the hope of a more comfortable and prosperous tomorrow. But for those of fifty years or more the past outweighed the future. They had neither the time nor the desire to recreate themselves. When they looked back over the ship’s rail they saw, receding into the distance, everything that they had known, everything that they had loved and everything that they had been. ‘May God forgive those,’ said Finlay MacQueen, who was then sixty-eight years old, to a younger emigrant on HMSHarebell, ‘that have taken us away from St Kilda.’

John MacDonald would have little time to mourn. The fifty-nine year-old moved to the Highland ‘capital’ of Inverness on the north-eastern coast, where he took a job as a labourer with the county council’s roads department. John was accommodated in the Old Toll House at Culcabock on the main road east of the town, a picturesque but crumbling monument which he described as ‘the worst place that my eye ever came across’. He died seven months after leaving St Kilda, in the Northern Infirmary, of acute pancreatitis on 18 April 1931. John MacDonald’s death certificate was signed by a nephew who was living in Stornoway on the island of Lewis, two days’ journey from Inverness.

A significant difference between the St Kildan evacuees and the emigrants from other Hebridean islands was that the St Kildans had no neighbouring settlement in which to relocate. The people of Mingulay could and did go to nearby Vatersay and Barra, where they already had friends and family. Many of the people of Rona shipped south to newly nationalised land on Raasay, land which they knew well partly because their grandparents had been cleared from it in the nineteenth century. The families from the Crowlins sailed across just two miles of sea to Applecross. The people of Scarp and Taransay transferred to the much larger parent islands of Harris and Lewis; the people of Heisker crossed over to Uist.

There were no such close and comforting neighbours to St Kilda. Some earlier emigrants had already moved to the Outer Hebrides, but when it came to an organised evacuation the authorities reasoned that almost any place in Scotland would be as suitable a destination as could be expected. If there was some Gaelic spoken in that place, so much the better. But the priority was to transfer the St Kildans into the twentieth century; to give them jobs and wages and access to trains and telephones and all the other benefits of modern civilisation.

The Forestry Commission, a government body which had been established in 1919 to replenish British woodlands by planting trees chiefly in Scotland, shouldered the responsibility for employing and housing most of the islanders of working age. In 1930 the Forestry Commission operated almost exclusively on the mainland. It had recently acquired a large estate by Lochaline in the Gaelic-speaking district of Morvern on the west coast overlooking the Sound of Mull. Three-quarters of the evacuees, including Rachel Gillies’s family, were resettled there. Much was made, then and later, of the apparent incongruity of moving people from a treeless island to live and work in a timber plantation. That was a condescending misinterpretation of the St Kildans. They were not aliens from the barren Planet Zog. Even those few of them who in 1930 had never previously left Hirta knew what a tree was, just as seventeen year-old Rachel Gillies knew about the cinema before watching The Understanding Heart on the big screen in Fleetwood. They had been educated; they read books. More importantly to the Forestry Commission, they knew how to cultivate plants in difficult conditions.

Fifty-four-year-old Neil Ferguson and his fifty-four year-old wife Ann were despatched to Tulliallan on the border of Perthshire and Fife in the south-east of Scotland. Its name derives from tulach-aluinn, meaning ‘beautiful knoll’, but twentieth-century Tulliallan was no longer a Gaelic-speaking area, and it was about as far from St Kilda as the Fergusons could travel without falling into the Firth of Forth. But the Forestry Commission had its main tree nursery in Tulliallan, where Neil could engage in relatively light work.

Their son and daughter-in-law, thirty-one year-old Neil Junior and his thirty-nine year-old wife Mary Ann, went to work and live at the Forestry Commission’s more northerly Ardnaff plantation by Strome Ferry, close to the railhead and port at Kyle of Lochalsh in Wester Ross and 60 miles due north of the plantation at Lochaline by the Sound of Mull. Finlay MacQueen, who was Mary Ann Ferguson’s father and whose English was still wanting, joined them at first in that Gaelic-speaking part of north-western Scotland.

One of Finlay’s sons, John MacQueen, had joined the Royal Naval Reserve during the First World War and had since settled in Glasgow. In October 1930, two months after the evacuation, armed with a note which read ‘Please see the bearer on the through train to Glasgow. He has no English’, Finlay travelled south to visit John.

Inevitably, Finlay MacQueen was run to ground in Glasgow by journalists, who found the old man in an uncompromising mood. ‘I wish to God that I had never left [St Kilda],’ he told them, ‘in a voice which trembled with feeling’. Four trains a day ran on the Kyle-to-Dingwall line through the small and otherwise peaceful settlement at Strome Ferry. ‘A train runs within two yards of our new house,’ said Finlay, ‘and I am terrified.’ He had been unable to get a smoke for a fortnight, he asserted, because he ‘dared not venture out to buy matches’.

‘Finlay is to go back to the Kyle of Lochalsh,’ concluded one report, ‘but not to stay. He intends to collect his effects and go elsewhere.’

Finlay MacQueen did leave Wester Ross, but not for Lochaline, let alone the Hebrides. He packed his effects and travelled to the anglophone south again, to join his near-contemporaries Neil and Ann Ferguson in Tulliallan, where he lived in a farm building a long way from the nearest railway line. He died there of heart failure ten years later, in December 1941. He was seventy-nine years old.

On Sunday, 31 August 1930 the Observer newspaper soliloquised,

After a thousand years of human habitation, the winds and the sea-birds have St Kilda to themselves. Economic circumstances have brought about the migration, and while the islanders find a new, and, as they hope, a fuller life by the Sound of Mull, nothing will remain but the ruins of their homes and the wild sheep on Boreray to mark the long settlement.

Sentimentalists in club smoke-rooms may be sorry for the change and sigh for ‘St Kilda no more’, but the islanders will know better. The retreat just conducted by the British Navy was a work of necessity and mercy.

The islanders have not been self-supporting for some years. Starvation faced them in the coming winter. They are not a helpless people, but accident and emigration reduced the man-power below the necessary minimum …

In a few days the steamer Hebrides, making her last call for the year, may disembark a party of tourists to sentimentalise over the deserted village. Hereafter the island will be left to itself and winter. Nor is it likely that many people will go there again.

The proprietor, MacLeod of MacLeod, is against repopulation, and the Department of Health is glad to be rid of a problem in communications. Without the ‘picturesque natives’ the island will be of small interest to tourists and in a few years may be forgotten by all but trawlermen who shelter in its lee from the North Atlantic gales.

Some of the Observer’s correspondent’s points were accurate and some were mistaken. Some were and remain debatable. But the newspaper’s closing sentence could not have been more wrong.

TWO

Amazon Queens, Norsemen and Gaels

THEY WERE SHAPED by fire and ice. The four islands, their immense sea stacks and numerous smaller skerries and rocks which comprise the St Kilda archipelago are the remains of a volcanic crater which blew between fifty-five and sixty-five million years ago. The volcano was then part of a landmass which we now know as the Lewisian Complex in the Hebridean Terrane of the foreland of the prehistoric continent of Laurentia.

Two hundred million years ago in Laurentia, the north-west of Scotland was adjacent to the north-east of North America. They then drifted apart, and are still drifting apart, inch by inch over millennia, and the continent of Laurentia divided into America and Eurasia.

St Kilda would have been one of the tallest and most powerful volcanoes in the old Laurentian foreland. It erupted in roughly the same geological period as the mountains of Mourne in Ireland and the Cuillins of Skye. The results were strikingly similar: jagged, shattered ranges of igneous rock which look, as the travel writer H V Morton said of the Cuillin ridge, like ‘Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” frozen in stone and hung up like a colossal screen against the sky’.

As the European and American regions of Laurentia separated, the Atlantic Ocean flowed into the void. Unlike the Cuillins and the mountains of Mourne, the peaks of St Kilda were stranded by the rising sea and left ultimately 40 or 50 miles west of the barrier islands of the Outer Hebrides. Then the ice came, and the far north of Scotland was once again linked by gelid water to the far north of America.

We may therefore summarise the prehistory of St Kilda as firstly a volcanic dome towering over a hilly primeval landscape, carpeted by ferns and inhabited by dinosaurs. The volcano then exploded, leaving behind black shards and splinters and crags and cliffs. Those dramatic remnants were later surrounded by salt water. The Earth’s temperature fell, and St Kilda became a cathedral of rock covered in ice and snow, its glittering white steeples looming out of a frozen sea.

That Ice Age, from which Scotland is still emerging, began some fifty million years ago. It has regularly been interrupted by intervals of warmer weather, which are known as interglacials. There was an interglacial between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago. At that time our hominid ancestors had been foraging in the north of the continent of Eurasia, to which the British Isles were connected by a large land bridge, for hundreds of thousands of years. There is evidence of Palaeolithic settlement during a benign interglacial 800,000 years ago at Happisburgh on the Norfolk coast. According to Professor Chris Stringer FRS, those first Britons shared a grassy floodplain with ‘a diverse range of animals … such as primitive mammoths, rhino, horse, hyena and even sabre-toothed cats’.

Some of those pioneers took advantage of periods of warm weather to travel through the northern forests to the outer tips of Scotland. Flint artefacts discovered in South Lanarkshire and on the Hebridean island of Islay are residual evidence of that fact. Most other traces of their presence were scoured clean by the glaciers and meltwater of the last brief Ice Age. It descended some 12,900 years ago and once again covered with an ice sheet the whole of Scotland (with the north-easterly exceptions of the Orkney and Shetland islands, a few miles around John O’ Groats and a few miles around Fraserburgh), the entire north of England and almost all of Wales and Ireland. The Hebrides were frozen and western waters from the Minch to the Irish Sea turned into pack ice.

That ice sheet began to retreat 11,500 years ago and has not yet returned. As it melted, vegetation and animals put down roots and took up residence in the high lands and the islands of northern Britain.

The outcrops which would become the British Isles were then connected like a hammerhead to the Eurasian continent. A 100-mile-wide extension of Belgium and the Netherlands reached westward to join Britain between Margate and The Wash. The prehistoric Stone Age settlement at Happisburgh, whose remains in modern times are on the English coast of the North Sea, was then an inland continental community, surrounded by freshwater courses, pools and marshes. For several thousand years, until the North Sea began to rise and cover that land bridge some 8,500 years ago, pedestrians were able to make their way to and from Rotterdam and East Anglia with relative ease. Even when ‘Doggerland’ was inundated, the few sea miles between the east of the new main island of Britain and the north-west of the Eurasian continent were navigable.

Post-Ice Age human colonisation began therefore in the south and east of Britain and travelled steadily north. There were Palaeolithic people in Lanarkshire 14,000 years ago and there were Mesolithic (the middle period of the Stone Age) settlements in the mild south-east of Scotland by 8500 BC. Over the next 4,000 years until around 4000 BC, when the hunter-gatherer Mesolithic Britons propagated the slightly more settled Neolithic Britons with their budding interest in agriculture, they hunted and gathered in the north-western islands of Rum, Colonsay, Skye, Islay, Jura and Oronsay and in such mainland littorals as Applecross. Those people were of course to be found in greater numbers elsewhere, but beside the Firths of Forth and Clyde their middens and arrowheads were ploughed over and buried beneath brick and concrete long before the nineteenth- and twentieth-century archaeologists arrived. In the sparsely populated Highlands and Islands their remnants were relatively undisturbed, if not preserved in peat bogs.

It is possible that Mesolithic hunter-gatherers set foot on St Kilda 6,000 years ago. Analysis of their Hebridean diet indicates the consumption of fish, shellfish, seals and seabirds. Birds, the surviving manifestation of the dinosaurs, were probably the first fauna to return to a post-Ice Age habitable St Kilda. There, in the absence of any serious predators – an absence which would last for thousands of years until being briefly disturbed by the arrival of homo sapiens – they thrived. Gannets, petrels, puffins and fulmars flocked to those distant cliffs, made homes upon the ledges and bred prolifically. The sea-going Stone Age men and women who found themselves looking westward from the Outer Hebrides are unlikely to have ignored so rich a source of protein. The first people to land at Village Bay on Hirta may have been a hunting party from North Uist or Lewis.

Mesolithic hunters left few footprints, and that proposition cannot be confirmed. Early in the twenty-first century our only certainty is that at some time after 3500 BC and before 1500 BC Neolithic people were living, for at least part of the year, on the main island of Hirta and the smaller island of Boreray in the archipelago of St Kilda.

They found a relatively hospitable island. Glacial retreat had carved two soft, substantial glens from either side of the main landmass of Hirta. In the east a bowl of fertile soil lay in the shelter of rolling hills. Loose rocks lay everywhere, but once they had been removed from the lowland machair and either deposited elsewhere or redeployed as building material, Hirta offered several acres of cultivable land. A few millennia later, in the eighteenth century AD, a land bridge would collapse and Dun would become a separate island. But in Neolithic times Dun was a promontory of Hirta. It was a crazy, jagged ridge emerging from the sea like an angry marine iguana in full profile. It formed one of the two strong arms of land that sheltered the small anchorage of Village Bay. The northerly arm was the rock-strewn mound of Oiseval, teetering over sheer cliffs and mysterious caves. The circular inlet of Village Bay is an almost perfect post-volcanic caldera.

Village Bay, with its natural harbour, good land and ample sources of fresh water, was an easy and obvious centre of settlement. Gleann Mor, the big western valley at the other side of a dip in the central hills, was more exposed to the prevailing Atlantic gales, less fertile and offered less suitable access to boats. But as the whole island was comprised of only 2½ square miles of land, and most of the rest of Hirta was barren hillside or peat bog, Gleann Mor was also settled by smaller and possibly more peripatetic groups of people. Although their cellular beehive dwellings were preserved and occupied as summer shielings during the annual transhumance until the twentieth century, it is unlikely that they were built to be used only seasonally. Their complex and durable construction suggests a permanent settlement in Gleann Mor during or before the Middle Ages.

One of those early dwellings was shrouded in myth and mystery by the later Gaels. They called it Taigh na Banaghaisgeich, the Amazon’s House. Martin Martin in 1697 reported that,

This Amazon is famous in their traditions: her house or dairy of stone is yet extant; some of the inhabitants dwell in it all summer, though it be some hundred years old; the whole is built of stone, without any wood, lime, earth, or mortar to cement it, and is built in form of a circle pyramid-wise towards the top, having a vent in it, the fire being always in the centre of the floor; the stones are long and thin, which supplies the defect of wood; the body of this house contains not above nine persons sitting; there are three beds or low vaults that go off the side of the wall, a pillar betwixt each bed, which contains five men apiece; at the entry to one of these low vaults is a stone standing upon one end fix’d; upon this they say she ordinarily laid her helmet; there are two stones on the other side, upon which she is reported to have laid her sword: she is said to have been much addicted to hunting, and that in her time all the space betwixt this isle and that of Harries, was one continued tract of dry land.

Taigh na Banaghaisgeich, which in 1697 the St Kildans were using as a summer shieling while they pastured their cattle and sheep in Gleann Mor, may have been older than 100 years. It is medieval or earlier, and at the least offers an indication of the type of Stone Age dwellings in which the St Kildans lived until the Middle Ages. Those drystone sleeping chambered cells remained part of the architectural vernacular in the main settlement of Village Bay until the second half of the nineteenth century.

The Amazon’s House did not date back quite to the time of the Hebridean Terrane of the continent of Laurentia, when St Kilda was connected by dry land to the island of Harris, although it is curious that such Jurassic phenomena should have been reflected in human folklore. A late nineteenth-century writer reflected, however unscientifically, that ‘If there is any truth in my theory of the Warrior Queen, the first inhabitants of Hirta would have found their way there during the period succeeding the glacial epoch, while all this tract was still dry land, and the legend of how they got there would be handed down from one generation to another. Of course, the house that they now point out as the dwelling-place of their renowned Amazon may be of much later date than the lady herself, and the stories which Martin says were current in his time about her, but which he unfortunately does not record, may have been improvised or added to by the imaginative narrator, but I do not think that it is the sort of legend that would be invented in toto.’

The peat bogs offered a reliable source of fuel – in the form of slabs of black peat dug out of the earth and dried in the wind – on islands with no trees or other supplies of wood. Their presence could indicate, as the naturalist John Love suggests, that at some time before or shortly after the last Ice Age, in a warmer and calmer climate, St Kilda had been home to birch and hazel scrub. In 1758 Kenneth Macaulay reported that, ‘In the turfpits dug there, a prodigious number of trees, almost entire, are frequently found, which must have been buried in these places, after having been killed or plucked away from their roots, by the vast quantities of earth which had been washed away from off the faces of the hills above.’ Peat is no more than decayed vegetation, however, and at least some of the bogs on top of Mullach Mor, on the upper slopes of Gleann Mor and on Cambir may simply have been the seasonal deposits of dead turf which rotted and accumulated over centuries before humans arrived to excavate them with stone or iron tools.

Beyond Gleann Mor, a few hundred yards off the western tip of Hirta, sat the small, green grazing island of Soay, which at first was part of St Kildan common land but which later was reserved for the proprietor’s stock. Six miles north-west of Village Bay was the group’s third island of Boreray and its two prodigious stacks of Armin and Lee. The sea cliffs below the 1,400-foot summit of Conachair on Hirta are easily the highest in Britain (they are also the eleventh highest in Europe), and Stac an Armin and Stac Lee are, at 643 feet and 564 feet, respectively the highest and second-highest sea stacks in the British Isles. Stac an Armin is a fine arrow piercing the sky, and Stac Lee a vertiginous axehead of a rock. They are all but sheer from sea-level to summit, and gannets and other birds nest in their thousands on their diagonal thinly etched ledges. Before the arrival of humans and after their departure, in spring and early summer the upper slopes of both stacks have been made as white as an Alpine summit by the presence of thousands of young gannets and their guano. The island of Boreray had a high sloping pasture for sheep and even the possibility of some crop cultivation. But its main attraction was the seabird harvest from the Boreray cliffs and from Stacs an Armin and Lee, upon whose sheer rock faces bothies were somehow built by the bird-catching cragsmen of Hirta to offer shelter from the weather and even a temporary home, as if a window cleaner were to pitch a tent halfway up the Empire State Building.

That lethal, thrilling, skilful activity was and remained the central function and support of human settlement on the St Kilda islands. Whether in clambering up Stac Lee or being lowered on a homemade rope down the dizzying cliffs of Conachair, bird-catching required a superhuman quantity of courage, the skills, coordination and upper-body strength of an extreme rock climber and Olympic gymnast combined, and the indifference to heights of the Mohawk people who were employed to build Manhattan’s skyscrapers. It was a valuable activity because for centuries a bottomless supply of seabird meat insulated the entire St Kildan community from the famine years which afflicted other, more agricultural Hebridean islands. It was also profoundly masculine. From the Stone Age to the twentieth century, seabird hunting in St Kilda offered its men the opportunity for physical assertion, displays of courage and strength and adrenalin rushes that others might find only in battle.

The Neolithic people left behind them stone hoes, knives, axes, grain grinders and shards of pottery. The pottery alone indicates that those prehistoric St Kildan settlers were from the Western Isles. It was Hebridean Ware, and in the words of the archaeologist Professor Ian Armit, Hebridean Ware pottery is a ‘localised style, so far known only from the Western Isles of Scotland’:

Hebridean vessels are characteristically deep jars with multiple carinations; their upper parts are profusely decorated, generally with incised herringbone patterns … elaborately decorated pottery was to be a recurrent trait of Hebridean prehistory until almost the end of the Iron Age. The quantities of ceramics and the effort put into their decoration shows that pottery played an important role for the communities of the Hebridean Neolithic. In functional terms it provided containers for cooking and food storage. It also held offerings which were placed in the chambered tombs. It may also have played a role in feasting and ritual activities …

Shortly before or shortly after the birth of Christ a small souterrain was dug out and walled in Village Bay on Hirta. The word comes from the French sous terrain, under ground, and although the structures are found throughout Atlantic Iron Age Europe, the majority of good surviving specimens are in the early Celtic domains of Ireland and Scotland.

Souterrains were hallmark buildings of that culture. Hardly a single populated Hebridean island was without one. They were essentially underground passageways and chambers lined with slabs of stone or wood. They appear to have had no particular religious significance, nor were they used for burial. Souterrains were dwelling places, subterranean storage facilities or defensible hiding places, or all three.

The miniature example on Hirta later became known to locals as Tigh an t-Slithiche, House of the Fairies. Significantly, the souterrain Tigh an t-Slithiche was located a few yards from the medieval and modern settlements in Village Bay. The later inhabitants had known of its existence since the middle of the nineteenth century and probably earlier, without comprehending its historical importance. Until the middle of the twentieth century it was believed, as the newspaper reports of the evacuation in 1930 reiterated, that St Kilda had been populated for about 1,000 years. The presence of Tigh an t-Slithiche adds another 1,000 years to that figure, and possibly more. It certainly indicates a settled prehistoric community.

There are on Hirta, Soay, Boreray and even on the precarious top of Stac an Armin almost 1,400 ruined or intact cleitean. Those unique drystone sheds-cum-pantries define the landscape as certainly as bird-hunting defined the people. They are on the tops of mountains, the bottom of glens and the sides of cliffs. They sit in clusters, in rows and in isolation in surprising places, like the homesteads of some alien parallel civilisation. Village Bay is a shanty town of cleitean – they far outnumber the houses, old and new, even on the precious arable land – but nowhere in St Kilda is out of sight of a cleit.

Cleits are oval stone igloos which vary in size from that of a dog-kennel to a small cottage. The term, if not the construction, is common throughout the Scottish Gàidhealtachd. It can mean a quill or feather, which, probably coincidentally, describes some of what was stored in St Kilda. A cleit is also the Gaelic word for a natural rather than a man-made feature; it is a rocky outcrop on land or sea. At the foot of the cliffs of Conachair in Hirta there are reefs named Na Cleitean. The word derives from the Old Norse klettr, klett or klet, which simply means rocks (the Orkney surname Linklater is a conflation of lyng and klettr, meaning heather rocks). But only in St Kilda was the corruption of the Norse noun klettr into the Gaelic noun cleit adopted as the architectural description of a building made from stones, as well as still being applied in its more usual context as a feature of the landscape. That is unusual but not inexplicable. When the St Kildans first began to build their unique storage sheds they simply named them after the familiar geological phenomena which the cleitean best resembled – the large rocks which butted out of the sea and hillsides all around them.

As with almost all constructions on St Kilda the people made a virtue of the necessity of building without wood. Since no trees grew on their islands, if they needed it they were always almost entirely dependent on imported timber. Planks and logs were washed up as flotsam or saved from wrecked ships, but most of their wood came in the steward’s galley from Harris, where it was also rare and therefore doubly valuable. Wood was a precious material in Village Bay and was used sparingly. Whatever their size, cleits have several main features in common. One is their sloping sides, which reach incrementally inwards until the roof can be spanned with rectangular slabs of rock. The slabs of rock are then amply covered with turf, which develops its own little self-sustaining eco-system on the top of each cleit and restricts the ingress of rain-water – not unlike the ‘green’ or ‘living’ roofs of late twentieth-century architecture. They have no windows and their other common feature is their single entrance at ground level, some so tiny that only a child could creep in, some half the height of a standard doorway.

Until the very end in 1930 they were used for cold storage, as ventilated larders for seabirds and mutton, as sheds for tools, nets and hay, and even for storing peat. (The last function was as unusual in north-western Scotland as the cleitean themselves. Everywhere else peats were, and are, cut outside, dried outside and stacked outside beside the dwelling place.) A visitor in the 1880s recorded that ‘Formerly they were used by the people for drying birds … In these houses the St Kildian crofter [now] dries his grass and grain. He has a habitual distrust of the weather, and never attempts to dry any of his crops in the open air.’ Their deployment into modern times – cleits were still being built as well as used in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – distracted outsiders from their actual antiquity. Later archaeology has suggested that some of them were in continuous use for at least 1,000 years.

Until the twenty-first century it was thought that all permanent human habitation had been restricted to Hirta, and that the islands of Soay and Boreray were occupied only during seasonal bird-hunts and sheep gathering. But in the summer of 2011 archaeologists working for the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland and the National Trust for Scotland dug out an intact stone building with a corbelled roof among three settlement mounds from beneath the turf and soil on Boreray. This was the legendary construction known as Taigh an Stallair, or Staller’s House. It was examined in the middle of the eighteenth century by Kenneth Macaulay. He wrote:

At the distance of many ages back (the precise time cannot be ascertained) a bold, public-spirited, or self-interested person, whose name was Staller, or the man of the rocks, headed an insurrection, or rebelled against the governor or steward, and at the head of a party engaged in the same disloyal conspiracy (or rather struggle for liberty) possessed himself of Boreray, and maintained his port there for some time. Here he built a strange kind of habitation for himself and his accomplices. – The story is of an antient date, but is, by this extraordinary monument, in some degree authenticated.

The house is eighteen foot high, and its top lies almost level with the earth, by which it is surrounded; below it is of a circular form, and all its parts are contrived so that a single stone covers the top. – If this stone is removed, the house has a very sufficient vent. – In the middle of the floor is a large hearth. Round the wall is a paved seat, on which sixteen persons may conveniently fit. Here are four beds roofed with strong flags or stone lintels, every one of which is capable enough to receive four men. To each of these beds is a separate entry; the distances between these different openings, resembling in some degree so many pillars.

The rebel (or rather friend of liberty) who made this artificial cove, had undoubtedly sufficient reasons good enough to justify his taste of architecture; that he must have wanted timber to build in the common way is morally certain; it is equally so, that he must have been apprehensive the enemy would invade his little kingdom in the nighttime.

Taigh an Stallair entered St Kildan folklore in the following tale, told by the elderly Euphemia MacCrimmon to a visitor in 1862:

The house is called Taigh an Stallair, after the name of him who built it. It was built on stone pillars, with hewn stones, which it was thought were brought from the point of the Dun. It was round inside, with the ends of long narrow stones sticking through the walls round about, on which clothes might be hung. There were six croops or beds in the wall, one of them very large, called Rastalla; it would accommodate twenty men or more to sleep in. Next to that was another called Ralighe, which was large, but rather less than the first. Next to that were Beran and Shimidaran, lesser than Ralighe, and they would accommodate twelve men each to sleep in. Next to that was Leaba nan Con, or the Dog’s bed, and next to that was Leaba an Tealich, or the Fireside bed. There was an entrance [passage] within the wall round about, by which they might go from one croop to another without coming into the central chamber. The house was not to be noticed outside, except a small hole on the top of it, to allow the smoke to get out and to let in some light. There was a doorway on one side (where they had to bend to get in and out) facing the sea, and a large hill of ashes a little way from the door, which would not allow the wind to come in. Bar Righ was the name of the door. The present inhabitants of St Kilda [in 1862], when in Boreray fowling, or hunting sheep to pull the wool of them, which is their custom instead of shearing them, used to live in the house until about twenty years ago, when the roof fell in. Some of the croops are partly to be seen yet.

The building and settlement mounds looked over a primitive field system and crop terraces. Whoever created them, whatever they were named, had lived there.

‘This is an incredibly significant find,’ said the RCAHMS surveyor Ian Parker, ‘which could change our understanding of the history of St Kilda. This new discovery shows that a farming community actually lived on Boreray, perhaps as long ago as the prehistoric period.

‘The agricultural remains and settlement mounds give us a tantalising glimpse into the lives of those early inhabitants. Farming what is probably one of the most remote – and inhospitable – islands in the North Atlantic would have been a hard and gruelling existence. And given the island’s unfeasibly steep slopes, it’s amazing that they even tried living there in the first place.’ The unfeasibly steep slopes may have provided part of the reason. Boreray was an easily defensible island. The gradient of its cultivable land would not have deterred Hebrideans who were accustomed to ploughing on the sides of hills.

It is possible, although archaeologists now consider it unlikely, that there was also a megalithic stone circle on tiny Boreray. In 1764 Reverend Kenneth Macaulay reported there ‘a Druidical place of worship, a large circle of huge stones fixed perpendicularly in the ground, at equal distances from one another, with one more remarkably regular in the centre, which is flat in the top’. A hundred years later a visitor to St Kilda said that ‘there was a temple in Boreray built with hewn stones. Euphemia Macrimmon remembers seeing it. There is one stone yet in the ground where the temple stood, upon which there is writing: the inhabitants of St Kilda built cleitean or cells with the stones of the temple.’

Those were the people who built the oldest surviving crannog pile dwelling of Eilean Domnhuill in Loch Olabhat in North Uist around 3000 BC, and who therefore must have had a hand in inventing that architectural form. Crannogs, artificial inhabited islands, are almost unique to the lochs and rivers of Scotland and Ireland (one has been discovered in Wales), where they were iconic structures from prehistory to the early centuries AD.

They were the people who between 2900 BC and 2600 BC