Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

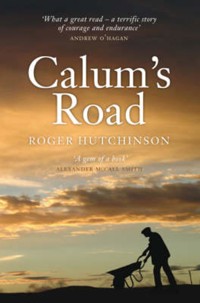

'An incredible testament to one man's determination' – The Sunday Herald Calum MacLeod had lived on the northern point of Raasay since his birth in 1911. He tended the Rona lighthouse at the very tip of his little archipelago, until semi-automation in 1967 reduced his responsibilities. 'So what he decided to do', says his last neighbour, Donald MacLeod, 'was to build a road out of Arnish in his months off. With a road he hoped new generations of people would return to Arnish and all the north end of Raasay'. And so, at the age of 56, Calum MacLeod, the last man left in northern Raasay, set about single-handedly constructing the 'impossible' road. It would become a romantic, quixotic venture, a kind of sculpture; an obsessive work of art so perfect in every gradient, culvert and supporting wall that its creation occupied almost twenty years of his life. In Calum's Road Roger Hutchinson recounts the extraordinary story of this remarkable man's devotion to his visionary project.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 264

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Calum’s Road

Roger Hutchinson is an award-winning author and journalist. In 1977 he joined the weekly West Highland Free Press, and is still attached as a columnist to that paper. His book The Soap Man (Birlinn 2003) was shortlisted for the Saltire Scottish Book of the Year in 2004, and Calum’s Road was shortlisted for the Royal Society of Literature’s Ondaatje Prize in 2007.

Praise for Calum’s Road

‘An incredible testament to one man’s determination not to fold against a far-off bureaucracy and a physical symbol of someone who raged against the dying of the light’

Torcuil Crichton, Sunday Herald

‘An extraordinarily fine book’

James Hunter, West Highland Free Press

‘It helps the Gaelic cause no end that Calum MacLeod makes for such an appealing and admirable hero’

Harry Pearson, Daily Mail

‘Calum’s story is still an inspiration, even 18 years after his death . . . Roger Hutchinson’s book has become as unexpected a cause célèbre as the feat of engineering itself’

Steven Bowron, Sunday Post

‘Rings true in the characterisation of a man inured to hard toil, a crofter turning his hand to numerous tasks and skills to make a living, and yet intelligent and well-read, immersed in the political manoeuvrings of his day and a bearer of the history of his people. The book attains a lyrical quality in some passages, yet steers clear of sentimentality.’

Angus MacDonald, Northern Times

‘The inspiring tale of how an unforgiving landscape was conquered by one man’s determination’

John MacKay, Sunday Herald Books of the Year

‘A splendid book’

Professor Donald MacLeod, New Statesman

‘Roger Hutchinson points out that like good roads, parables not only survive the passing of the years but grow stronger with them, and Calum’s road has now established itself effortlessly in the folklore of the Highlands and Islands’

Bruce Stannard, Scots Magazine

‘A story of heroic anti-authoritarian, anti-socialist, anti-mainland, anti-council, anti-bureaucratic bloody-mindedness . . . It has an immediacy, feel and sympathy that does its subject full justice’

David Crane, The Spectator

‘A rare and impressive man is celebrated here . . . It’s inspiring to read about a man who wouldn’t succumb, wouldn’t let the government threaten his way of life’

Sue Baker, Publishing News

‘It’s quite possibly the mythic, almost Sisyphean element written into this modern-day parable of the difference one man can make that renders the tale compelling’

Steven Carroll, The Melbourne Age

‘A tremendous read. Not just of construction, determination and a desire to better a community that had shrunk through the clearances. But of an attitude. If no council, organisation or body will help us, we must do something ourselves’

Tavish Scott, The Shetland Times

‘A gentle and justified tribute to the human spirit’

Ray Chesterton, Sydney Daily Telegraph

‘What a book. Social history, biography and commentary, by a man with deep affection and respect for the hero of his tale, as well as for all the other islanders involved’

David Ross, The Herald

‘A brave story about a brave man’

Mick Herron, Geographical Magazine

‘A modern parable of human endurance’

Mary Miers, Country Life

Calum’s Road

Roger Hutchinson

This ebook edition published in 2011 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2006 by Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © Roger Hutchinson 2006 Maps drawn by Rachel Ross

The moral right of Roger Hutchinson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ebook ISBN: 978-0-85790-002-9

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from

(Highlands & Islands Arts Ltd) towards the publication of this ebook

The publisher would like to dedicate this book to Joyce McLelland (1921–2006), an extraordinary person who was loved by all who knew her

Do mhuinntir Ratharsair, na bh’ann, na th’ann ’s na tha ri teachd

Contents

Preface

Maps

The Island of Strong Men

The Book of Hours

A Few in the North Would Not be Catered For

No Chance of Being Run Down by a Car

A Kind of Historical Justification

The Last Man Out of Arnish

Notes

Bibliography

Preface

In February 1979 I had been working as a journalist on a Highland newspaper for fifteen months. There arrived in the editorial office notification of some council work that was apparently due to commence on a crofter’s homemade track on the island of Raasay. It was, I was told, a good story.

I took the small car ferry from Sconser in Skye to Raasay. I then motored up a long and winding single-track road to Brochel Castle in the north of the island. I took the car up a short, steep hill past Brochel and saw ahead of me an apparently limitless expanse of peat bog, heather and granite. A grey road wound across this solitude and disappeared out of sight. It was a perfectly good stone-based road – wide and gently contoured – but it had no tarmacadam topping. As a result it consisted of two parallel wheel tracks and a large central ridge inside trim rocky verges. The wheel tracks were worn and rutted with use. The central ridge was pronounced and studded with sharp stones that seemed likely to remove any ordinarily slung exhaust pipe. I could not realistically contemplate driving any further, and so I parked and looked around.

I knew from the map that this was the road in question and that the relevant crofter lived almost two miles further along it. It was cold and beginning to rain. It would soon be dark. The last ferry back to Skye would leave in little over an hour. I looked around the silent emptiness, shivered and resigned myself to missing the road’s maker.

Then there was some movement among the trees and shrubbery down the hillside to my right. A wiry man, five feet eight inches tall, walked easily up out of the vegetation, smiled at me shyly and offered his hand. He was, he said, Calum MacLeod.

He had a weather-worn telegraph pole balanced on his right shoulder. He had found it washed up on the shore – he pointed several hundred feet below us – and thought that it might be useful. I suppose we talked for fifteen or twenty minutes, but he did not rest the pole upon the ground, or show any indication of needing or wanting to put it down, until I asked to take his photograph. At that point he dropped it smartly and struck an experienced pose for the camera.

I now know that Calum was sixty-seven years old at that time, and I cannot say that he looked much younger. His face, beneath a battered tartan bonnet, carried the wear of a hard life spent out of doors. But I knew well enough that I, forty years younger than Calum MacLeod, could not in my late twenties, nor at any time after, have carried that telegraph pole even ten yards up the slope below us. If I had managed to move it five paces I would then have seized any opportunity or none to drop it and take a very long rest. ‘He was hardy, boy, was Calum’, as a shared acquaintance would say. ‘There was not an ounce of spare flesh on him.’

Calum told me about his road. He told me of the requests made in the 1920s to Inverness County Council by his parents and another ninety adults for a road. He told me – as he would tell so many others, in a tone that wavered between wry amusement and disgust – of how the council ‘kept putting it off and putting it off, until one after another of the young families left because there seemed to be no prospect of a cart road, and eventually there was nobody left but myself and my wife’.

He told me of his eventual conclusion, in 1964 – that was the year which he cited to me in 1979 – that if he did not build a road between Brochel and Arnish then nobody else would.

Not many months after that encounter I walked the length of Calum’s road for the first time. It was a glorious early summer’s day, but the one and three quarter miles appeared to be unnaturally long. Its surface was as before – which is to say that only the wheel ruts and the rugged central ridge prevented a car from traversing it – and it made for relatively easy hiking. But the terrain gave, and still gives, this highway epic proportions. Rarely can more than a quarter of a mile of Calum’s road be seen in any single stretch. Everywhere its next section disappears elusively from sight, around bends in the cliff-face, or down into glens, or off over hilltops. One and three quarter miles of a motorway (or, as Calum himself would say, of an Autobahn) is as quickly traversed as it is seen. One and three quarter miles of the road between Brochel and Arnish is like an odyssey.

And later I walked it again. And later still I drove one motorcar after another along it. With every passage it seemed increasingly not only to represent some kind of heroic last stand but also to be a parable. Not a myth or fable, for it is firmly grounded in fact, but a simple morality tale.

The test of its allegorical power would be, of course, endurance. Like good roads, parables not only survive the passing of the years but grow stronger with them. And Calum’s road has established itself effortlessly in the folklore first of the Highlands and Islands and then of Scotland, and steadily thereafter of the United Kingdom and the whole great wider world beyond Loch Arnish. A curious physical process seemed to be under way in which, as the Gaelic Hebridean society which Calum MacLeod fought for, embodied and loved slipped into history, so his immense, defiant gesture became increasingly significant. A cultural mountain had eroded, but as it was washed away the remnant bedrock of Calum MacLeod’s road appeared as haunting and precious as fossilised footprints on any other distant shore. Television programmes lingered over it. A strathspey in D major was written about it by a member of the popular band Capercaillie. In the early summer of 2004 an exhibition of art entitled ‘Calum’s Road’ was mounted in the Skye gallery An Tuireann. It featured pottery created by Patricia Shone, who, according to one critic, ‘took clay over to Raasay and pressed it on to the tracks of the famous road, which resulted in beautifully textured jars with uneven edges and peaty colours, which I could not resist touching’.

Calum’s road started to feature – in prose that was either breathless or brutally factual – in the guidebooks. ‘Those who make it to the north of the island’, reads one such entry, ‘may wish to note that the two miles of road linking Brochel to Arnish were the work of one man, Calum MacLeod. He decided to build the road himself after the council turned down his requests for proper access to his home. He spent between 10 and 15 years building it with the aid of a pick, a shovel, a wheelbarrow and a road-making manual which cost him three shillings. He died in 1988, soon after its completion, and to this day it is known as “Calum’s Road”.’ It has been described as a wonder of the modern world. There has been mention made in the twenty-first century of applying to UNESCO to have Calum’s road recognised as a World Heritage Site.

There were many disputes between councils and communities concerning access roads in the Highlands and Islands in the twentieth century, and there doubtless will be more in the twenty-first. Why, then, has Calum’s road become such an enduring parable? Why not Rhenigi-dale in Harris or Drinan in Skye? Why not all of the arterial routes of South Uist or the road to Applecross in Wester Ross? The answers are elementary. The first is that Calum MacLeod’s community was the smallest of the small, the most neglected of the neglected; it was located on the furthermost point of one of the least prominent of the lonely Hebrides. And the second is, of course, that a road was finally built to Arnish not by the council, or the Department of Agriculture, or the Royal Engineers, and not even by a community, but by one extraordinary man.

There is clearly a risk – if ‘risk’ it is – of sentimentalising a definitively robust and unsentimental story. I am not immune to such things, but, luckily, the story itself seems to be. The metaphor, the parable of Calum’s road, inspires flights of fancy. The evident engineering, the solid rock and tarmacadam of Calum’s road inspires a mostly bewildered but deep and lasting respect. Whatever else is said and written about this subject, the least firmly grounded of visitors to Arnish will leave with one essential, important conclusion: that here lived a man who desired not fame and money, nor television and radio programmes, nor medals and recognition by UNESCO, nor paragraphs in travel guides, nor tributes in magazines and newspapers and books; a man who would have been astonished and bewildered by the tribute of an exhibition of art. Calum did not even want a driving licence. He merely wanted a road.

As I hope the dedication of this book makes clear, I owe thanks to many people. I am especially grateful, for their time, experience and expertise, to those former residents of Arnish and Torran Julia MacLeod Allan, Charles MacLeod, Jessie Nicolson and John Nicolson. A number of council and library officials were helpful beyond the call of duty, particularly Gordon Fyfe, Fiona MacLeod and Sam MacNaughton in Inverness, and Alison Beaton, Carol Campbell, David MacClymont, John Macdonald and Moreen Pringle in Skye. Ian MacDonald of the Gaelic Books Council was instructive on the subject of Calum MacLeod’s writing. Kirsty Crawford at the BBC archives in Glasgow tirelessly excavated distant radio and television programmes. Lorna Hunter of the Northern Lighthouse Board and Chris Henry of the Northern Lighthouse Museum directed an arc-light on the history of the manned lighthouse in Rona. The recollections and corrections of John Cumming, Gina Ferguson, John Ferguson, Donald Malcolm MacLeod and Alistair Nicolson, all from Raasay, were invaluable. Houston Brown, Cailean Maclean and John Norman MacLeod assisted this project with characteristic enthusiasm. Norma MacLeod freely offered essential advice and information. The personnel and facilities at the archive libraries in Stornoway, Portree and Inverness, and at the National Archives of Scotland in Edinburgh, were as accommodating as ever. My agent, Stan, was a pillar of strength, and Hugh Andrew and his team at Birlinn were supportive to a fault. And, once more, the extraordinary patience and skill of Joan MacIntyre made the researching of this book more of a pleasure than I had any right to expect. All errors and omissions are mine, not theirs. Moran taing.

Roger Hutchinson

Isle of Raasay, 2006

The Island of Strong Men

There are indeed no roads through the island, unless a few detached beaten tracks deserve that name.

James Boswell, Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides, 1773

On a spring morning in the middle of the 1960s a man in his fifties placed into his homemade wooden wheelbarrow a pick, an axe, a shovel and a lunchbox. He trundled this cargo south from his crofthouse door, down a familiar, narrow, rutted bridle path, up and down rough Hebridean hillsides, along the edge of hazardous cliff-faces, through patches of bent and stunted hazel and birch and over quaking peat bogs.

After almost two miles he stopped and turned to face homewards. Before him and to his left were steep banks of bracken, turf, birch and hazel. To his right, green pastureland rolled down to the sea. There were sheep on this pasture, and, close to the shore, a small group of waist-high stone rectangles which once, a century ago, had been the thatched cottages of a community called Castle. The vestigial masonry of a medieval keep teetered on an outstanding crag a few yards from the deserted homesteads, melding into the bedrock so naturally that, 500 years after they were first erected and 300 years since they were last occupied, it had become difficult to tell from a hundred yards away where the remnant walls of the man-made fortress finished and the natural stone began.

Then, alone in an empty landscape, he began to build a road.

He started by widening his workspace. He cleared the scattered clumps of wind-blasted native woodland which lay on either side of the old track. He chopped the dwarf trees down, and then he dug up their roots. He gathered the detritus carefully into piles at the edge of his planned route. He worked a long day. He was accustomed to working long days.

And at the end of that first long day, when he reassembled his equipment in the wheelbarrow and began his walk home, he had denuded several yards of ground. He had, in fact, accomplished slightly more than one-thousandth of a task which would take him twenty years to complete, which would pay him not a material penny and would cost him little more, but which would leave his manifesto marked in stone upon his people’s land.

His name was Calum MacLeod. He belonged to the township of South Arnish in the north of the island of Raasay.

This story is set in a very small place. On the North Atlantic rim of Europe, off the north-western seaboard of Scotland, lies a group of islands known as the Hebrides. There are several hundred Hebrides. None of them is very big, and none of them, in a global context, has ever been home to a great number of people. But almost all of these islands have at one time or another given shelter, hearth and home to somebody, somebody who could find a way of surviving and even thriving through eight months of winter and sixteen weeks of indifferent maritime weather.

The larger Hebrides are comparatively well known. They include Lewis, with its 21st-century population of 20,000 people, Mull and – for many the most resonant and celebrated of all – the rugged, sub-Alpine island of Skye.

Skye lies close to the littoral of the mainland Scottish Highlands. In several places a very strong mythological Celtic hero could have thrown a stone from Skye to Scotland, or taken a decent run-up and long-jumped over the Kyle of Lochalsh. But as the fingers of Skye grope further north and west, towards the island’s cousins in the Outer Hebrides, they move away from the hills and sheltered glens of Wester Ross and out into a troubled sea.

If Skye is thought of as somebody’s left hand, laid open, as if to be read, with fingers splayed, then the thumb and what palmists call the Mount of Venus in the south and west – which for convenience we will name the district of Sleat and Strath – lie nearest to the mainland. But our attention is drawn to the little finger straining towards the north and the chopping edge of the hand below it, facing the east.

These are the Skye districts of Trotternish and Braes, which are punctuated by the deep central harbour of market town and administrative centre, Portree. Under different geological circumstances the people of Trotternish, Portree and Braes would, in decent weather, enjoy an uninterrupted view across eleven miles of sea to the stark hills of Applecross on the western mainland.

They do not have this view because the archipelago of Raasay, Rona, Fladda and Eilean Tighe obscure it. Raasay, at twelve miles in length and two to three miles in width, is by far the largest of the four. Eilean Tighe, at about half a square mile, is the smallest. This raggedly beautiful quartet sits like a flotilla of small craft at anchor between the west coast of Scotland and the east coast of Skye.

From the looming coastlines of Skye and Applecross they can, to the uninformed eye, appear to be one land mass, so narrow and angular are the channels between them. The greatest bulk by far of this insular group is formed by the hills, grazings and meadows of central and southern Raasay. Those thirty square miles, to pursue our anatomical analogy, emerge from the sea like a muscular forearm.

But in their northern extremes the muscles wither and contract, and Raasay itself thins out into no more than a crooked finger of land, beckoning the northern sea. Upon this arthritic peninsula, around two wide bays known as Loch Arnish and Loch a’ Sguirr, stand a handful of old townships. To the west of the peninsula, accessible by foot over slippery rocks and seaweed at low tide, sits the small but relatively fertile island of Fladda. To the north of the finger, like an extra, disconnected joint, is the even smaller island of Eilean Tighe. And to the north of both Eilean Tighe and Raasay, at the other side of half a mile of treacherous sea, is Rona – Ronaidh, the island of seals – stony Rona, with its deep natural harbours, its caves and its arid dusting of soil. There are trees – stunted and bent, but still trees – on the northern finger of Raasay. There is pasture and even arable land on Fladda. There are neither worth mentioning on the four thin miles of Rona.

This group is the Hebrides in tiniest microcosm. The northernmost peninsula of Raasay and the islands of Fladda, Eilean Tighe and Rona are placid, seductive and immeasurably beautiful. Their physical attractions seem almost to influence perceptions of their weather, offering a curiously subjective microclimate to their indulgent inhabitants. When he was sixty-nine years old, and had lived for all but the first couple of those years in this Eden, Calum MacLeod of South Arnish would reflect with the practised eloquence of an ageing infatuate that ‘There is bad weather right enough. But the way Raasay is situated it’s as though it was sheltered by the island of Skye. For all the world it looks as if the island of Skye was sheltering Raasay in its arms. The high mountains of Skye, you see, they break the course of the Atlantic storms, and we don’t have them here.’

Storms or no storms, the islands of Calum MacLeod are so breathtaking that both Trotternish and Wester Ross welcome their interruption of the view. They are littered with the shards of broken hearts. And many of those hearts belong to people who have tried to live there.

Like all of the Hebrides, like all of the Scottish Highlands, these small islands are drenched in a history which has left its mark on every stone, every burn and every clump of birch. But, for obvious and practical reasons, most of the human history of Raasay and its satellites is to be found in the comparatively fertile central and southern districts of the largest island. Between prehistoric times and the nineteenth century, very few people lived in Rona, Fladda and Eilean Tighe – ‘tigh’ in Gaelic is the singular noun for a house – and only a handful of families occupied the northern Raasay townships of Torran, Arnish, Umachan and Kyle Rona.

Their circumstances have altered little through the centuries. When the educated young Skyeman Martin Martin gathered material for A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland in the 1690s he said of Rona – almost certainly from local hearsay rather than personal experience – that ‘this little isle is the most unequal rocky piece of Ground to be seen anywhere; there’s but very few Acres fit for digging; the whole is covered with long Heath’. Fladda, on the other hand, was ‘all plain arable Ground’ albeit only ‘about a Mile in Circumference’ – Fladda is almond shaped, measuring roughly a mile and a third in length and two-thirds of a mile in breadth.

Eighty years later, when the English philosopher Samuel Johnson visited as a guest of the hereditary proprietor John MacLeod in 1773, he noted that ‘Raasay is the only inhabited island’ in the group. ‘Rona and Fladda afford only pasture for cattle, of which one hundred and sixty winter in Rona, under the superintendence of a solitary herdsman.’

Johnson’s companion, the Scottish Lowland lawyer and diarist James Boswell, considered that ‘The north end of Rasay is as rocky as the south end. From it I saw the little isle of Fladda, belonging to Rasay, all fine green ground;– and Rona, which is of so rocky a soil that it appears to be a pavement.’

That our story is located in those distant and unpromising parts is thanks, chiefly, to a squalid episode in European history.

Samuel Johnson computed the 1773 population of Raasay to be between 600 and 900, which was almost certainly optimistic. Most other visitors and surveyors of the late eighteenth century suggest that 500 or 600 people lived there. He was also possibly wrong in maintaining that Rona was virtually uninhabited. An enumeration made by Church of Scotland ministers in 1764 – just nine years before the visit of Johnson and Boswell – declared that 36 people lived in Rona.

But it is certain that, other than those few ghostly and uncertain families eking out a living on the ‘pavement’ of Rona, in the last half of the eighteenth century effectively all of the archipelago’s inhabitants lived in Raasay, and most of them were settled in the centre and the south of that main island.

And it is equally certain that, within a tiny margin of possible error, fifty years later, in 1841, when a detailed official census was taken, 987 people lived in Raasay, 110 in Rona and 29 in Fladda. A dramatic population swing had started. A further fifty years after that, in 1891, when another national census was taken, the population of Raasay had fallen to 430, while the number of people living in Rona and Fladda had risen to 181 and 51 respectively, and there was a family of 8 living in the tidal outcrop of Eilean Tighe.

In the same period the populations of townships in central and southern Raasay disappeared. In 1861 there were 33 people in Holoman, on the central west coast. By 1891 there were just 5. In the same three decades the population of nearby Balachuirn fell from 49 to 26. In 1841 there were 30 people in the southern township of Eyre. Ten years later, in 1851, there were none.

In 1851, 233 people lived in North and South Fearns on the southern east coast of Raasay. Thirty years later, in 1881, nobody lived there. Leac, a mile along the east coast from Fearns, had a population of 70 in 1841, and was entirely depopulated in 1861.

Perhaps the most emblematic of all these vanishing Raasay civilisations, thanks to an eponymous epic elegy written in 1954 by the Raasay-born poet Sorley Maclean, was to be found another mile up the coast from Leac. John MacCulloch, who sailed past the townships of Upper and Lower Hallaig early in the nineteenth century, described ‘the green and cultivated land . . . on the tops of the high eastern cliffs, which are everywhere covered with farms, that form a striking contrast to the solitary brown waste of the western coast.’

In 1833 the people of Hallaig petitioned the Gaelic Schools Society in Edinburgh for some educational provision, insisting that ‘no less than 60 Scholars could be got to attend School’. In the census of 1841 the population of Upper and Lower Hallaig was enumerated to be 129 souls. Then came the eviction notices. By 1861 this busy place had been reduced to a shepherd and a labourer. By the time of the national census for 1891 the returns from Hallaig in Raasay amounted to one eloquent word: ‘Nil’.

And up the coast from the two Hallaigs lay North and South Screapadal, whose populations fell from 101 in 1841 to an official ‘Nil’ in 1861. And there were others, all of the others: Brae, Inver and Glame; Doiredomhain, two miles across the island from Screapadal, whose two families comprising 11 people in 1851 had gone by 1861; Manish, at the north-western shoulder of central Raasay, whose 41 people in 1841 had entirely disappeared within twenty years; and Castle, the community beneath the ruined medieval keep of Brochel, at the join between the strong arm of central Raasay and the crooked finger bending north to Arnish, Torran, Fladda and Rona.*

And the cause of this depopulation? Central and southern Raasay, the bulwark and the foodstore of the population of this island group since the Stone Age, was, between the middle of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, turned into a sheep run. Perhaps 500 or 600 people, perhaps half of the population, were evicted by force from Raasay in that period, or by the relentless attrition of unnecessary poverty. Some were transported to Skye, some to Australia, some to Canada, and others to unrecorded corners of the earth.

But some – a minority, but a substantial minority – stayed in the archipelago. We have seen how many of them moved to the formerly uninhabitable islets of Fladda, Rona and Eilean Tighe. Others moved to Torran, Arnish, Umachan and Kyle Rona. That thin, bent and lonely finger of land and its offshore islands had changed, in fifty short years, from an ill-considered outpost to the last redoubt of the native people of the small islands which lay between Skye and Wester Ross.

It was not an entirely stricken province. The inhabitants had not been sent to the deserts of Judea. There were both grazing and arable land in northern Raasay, as well as in Fladda and Eilean Tighe, there was summer grazing in the heather on the hills, and the surrounding sea was teeming with fish. But it was a district which had developed naturally over the centuries a certain, small, sustainable population, and which could not easily absorb more.

The mass eviction of Highland tenants by their nineteenth-century speculating landlords, eager to use their property to farm wool or breed deer, which led to the vacuuming of the human population of southern Raasay and the overcrowding of northern Raasay, Rona, Fladda and Eilean Tighe, was not of course confined to those four islands. It took place over a period of decades across all of the north and west of Scotland, and has come to be known as the Highland Clearances.

It brought in its wake a protracted period of social unrest throughout the area, which frequently sparked into militant action and violent clashes between land-hungry crofters, landless cottars, and those bodies of the law which were called upon by landowning interests to enforce their right to turn ancestral common grazings and arable land into private sheep runs or parks in which to hunt deer.

Many a government would have chosen to sit out the storm and let the cycle of skirmish and arrest continue. William Gladstone’s Liberal administration did not. In March 1883 Gladstone’s home secretary, Sir William Harcourt, announced that he was setting up a Royal Commission ‘to inquire into the conditions of the crofters and cottars in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland’.

The commission moved quickly. It held its first public hearing just two months later, on Tuesday 8 May, at Ollach Church – which was temporarily being used as a schoolroom – in Braes, in Skye, a mile across the sea from southern Raasay. Over the next five months the commission would travel from schoolhouse to drill hall to church premises, from Argyll to Shetland, Lewis and Caithness, meeting in 61 different places and hearing evidence – frequently through a translator of Gaelic – from 775 witnesses.