2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Renard Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

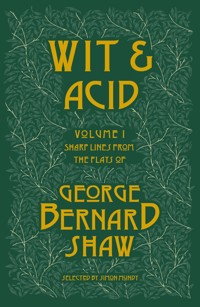

'If you want to tell people the truth, make them laugh, otherwise they'll kill you.' One of the most prolific and respected playwrights of the twentieth century, Bernard Shaw's legacy shows no signs of waning, and his beautifully written plays, laced with wry wit and invective alike, have seen countless performances over the years, their finest lines paraded in literary conversation and review. Meticulously selected by Simon Mundy, the Wit and Acid series collects the sharpest lines from Shaw's oeuvre in small neat volumes, allowing the reader to sample some of the very best barbs and one-liners the twentieth century has to offer, and this, the first volume, covers lines from the great writer's works published before 1911.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 48

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Wit and Acid

Sharp Lines from the Plays of

George Bernard Shaw

volume i

selected by

simon mundy

renard press

Renard Press Ltd

124 City Road

London EC1V 2NX

United Kingdom

020 8050 2928

www.renardpress.com

Extracts taken from plays first published between 1898 and 1911 (for more information see original publication dates on p. 84)

This edition first published by Renard Press Ltd in 2022

Edited text © Renard Press Ltd, 2022Introduction and selection © Simon Mundy, 2022

Cover design by Will Dady

Renard Press is proud to be a climate positive publisher, removing more carbon from the air than we emit and planting a small forest. For more information see renardpress.com/eco.

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, used to train artificial intelligence systems or models, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the publisher.

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe – Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia, [email protected].

contents

Introduction5

Wit and Acid11

Unpleasant Plays 1Widowers’ Houses13

Unpleasant Plays 2The Philanderer15

Unpleasant Plays 3Mrs Warren’s Profession17

Pleasant Plays 1Arms and the Man21

Pleasant Plays 2Candida27

Pleasant Plays 3The Man of Destiny31

Pleasant Plays 4You Never Can Tell41

Three Plays for Puritans 1The Devil’s Disciple45

Three Plays for Puritans 2Caesar and Cleopatra49

Three Plays for Puritans 3Captain Brassbound’s Conversion51

Man and Superman53

John Bull’s Other Island65

How He Lied to Her Husband69

Major Barbara71

The Doctor’s Dilemma75

Getting Married77

The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet81

Note on the Texts83

introduction

George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) was a writer who plied his trade with a volume and facility that his music-critic self would have recognised in Haydn, Handel or Saint-Saëns. He allowed his pen to carry on going with an ease that sometimes seems unstoppable. He wrote an awful lot of plays, containing an awful lot of words. He was a storyteller who loved the process of telling almost as much – perhaps more than – the story itself. There are moments in his plots where he turns a character inside out simply because the plot has to be resolved some time, even though the soliloquies arguing the opposite have been fierce enough to make such a change hard to credit.

He lived so long that he was born in the age of Dickens, shortly before his good friend Elgar, and died in the golden age of Hollywood in the year when James Stewart appeared in Winchester ’73 and as man who imagines a rabbit in Harvey. Much of Shaw’s writing was attached to the moment – the newspaper and magazine articles, the political pamphlets in support of the Socialist cause – and he never managed to get going as a novelist, though he tried. He was in his thirties before he turned properly from a critic into a playwright and the producers discovered him. Thereafter the plays flowed relentlessly for forty years.

He used the theatre for sharp social commentary, as a vehicle for debunking hypocrisy and as an antidote to establishment assumptions. As an Irish Protestant from a middle-class but relatively poor Dublinbackground who had struggled to make his way in London, he was as unimpressed by English imperial superiority as he was by Irish romantic nationalism. Most of all he was unimpressed by men – his father, schoolmasters, his mother’s companions. The result was that many of his plays revolve not just around strong women, but women who actively challenge their powerless status, legal and professional, in English society. They, along with the misfits, outcasts and reprobates, have all the best lines.

Shaw found that, though his novels made little headway, his plays were often initially more successful in print than on the stage, and this probably explains the length and detail of his introductory stage directions – so comprehensive that they would be hopelessly restrictive for any director or designer to follow, however intrusive the author tried to be in the production process. On the other hand, as historical essays, character studies and commentaries on interior design, they are superb. I have included one such almost complete: his portrait of a youthful Napoleon on campaign in northern Italy from The Man of Destiny – one of his shorter plays that on its first outing in 1897 made it no further into central London than Croydon.

The plays are not much easier to stage now, with many liable to outlast the patience of modern audiences. Shaw was always known for his resistance to producers making cuts. His themes were very much of their time, but the underlying issues – the tensions in marriage and gender relations, the absurdities of national stereotypes and the abuse of power – still hold good. His politics and obsessions are never far away, though he had enough self-knowledge to hold them up to the same satirical scrutiny as those he opposed. He was one of the founders of the Fabian movement, which fed the emerging Labour Party, but he was never a man comfortable with following a party line – the classic outsider artist. As he grew older, views which tune in well with left-wing causes of today – gender equality, the environment, vegetarianism, for example – strengthened. He would have had problems with our pandemic years, though, because he was fiercely against vaccination.

The tendency to write ten words when one would do means that Shaw’s lines do not have the one-liner punch of Oscar Wilde’s, Shaw’s close contemporary and Irish rival (it is perhaps no coincidence that Shaw’s London stage reputation