Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Fox Chapel Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

A no nonsense guide to turning wood on a lathe simple machines, easy skills to learn, fast results.

Das E-Book wird angeboten von und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 172

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

© 2010 by Skills Institute Press LLC

“Back to Basics” series trademark of Skills Institute Press

Published and distributed in North America by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc.

Woodworker’s Guide to Turning is an original work, first published in 2010.

Portions of text and art previously published by and reproduced under license with Direct Holdings Americas Inc.

ISBN 978-1-56523-498-7

eISBN 978-1-63741-556-6

Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Woodworker’s guide to turning : straight talk for today’s woodworker.

-- East Petersburg, PA : Skills Institute Press ; published and

distributed in North America by Fox Chapel Publishing, c2010.

p. ; cm.

(Back to basics)

Includes index.

1. Turning (Lathe work)--Technique. 2. Spindles (Machinetools)--Technique. 3. Woodworking tools--Maintenance and repair.4.Woodwork--Patterns. I. Title. II. Series: Back to basics (SkillsInstitute Press)

TT202 .W663 2010

684/.083--dc22 1011

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

Note to Authors: We are always looking for talented authors to write new books in our area of woodworking, design, and related crafts. Please send a brief letter describing your idea to Acquisition Editor, 1970 Broad Street, East Petersburg, PA 17520.

Because working with wood and other materials inherently includes the risk of injury and damage, this book cannot guarantee that performing the activities in this book is safe for everyone. For this reason, this book is sold without warranties or guarantees of any kind, expressed or implied, and the publisher and the author disclaim any liability for any injuries, losses, or damages caused in any way by the content of this book or the reader’s use of the tools needed to complete the projects presented here. The publisher and the author urge all artists to thoroughly review each project and to understand the use of all tools before beginning any project.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1: Setting Up

Chapter 2: Sharpening

Chapter 3: Spindle Turning

Chapter 4: Faceplate Turning

Chapter 5: Turning Projects

Glossary

What You Can Learn

Setting Up

This chapter is an introduction to the lathe and the tools and accessories needed for turning wood blanks into furniture parts, bowls, and other finished products.

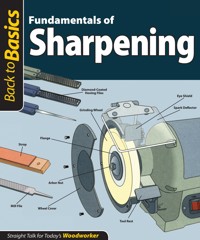

Sharpening

Dull cutting edges are not only more difficult and dangerous to use, but will also produce poor results, so take the necessary few minutes to sharpen your tools before you turn on the lathe.

Spindle Turning

Spindle turning involves mounting a wood blank between the machine’s headstock and tailstock and using a variety of turning tools to shape furniture parts such as chair legs and bedposts.

Faceplate Turning

Faceplate turning produces bowls and plates. It offers the wood turner a great deal of design freedom and completes a project in one single process.

Turning Projects

Spindles and bowls are only two of the seemingly endless variety of objects that can be turned, including goblets, table tops, and lidded boxes.

INTRODUCTION

The Basics of Turning Wood

As an industrial arts student at the University of Missouri many years ago, I first used the lathe to spindle turn the pedestal for a table. Since then, my techniques and knowledge have grown and matured—as has the field of wood turning itself. While I still enjoy making traditional spindle-turned furniture and objects, I also like what I see others accomplishing. Multi-centered and sculptural turnings have pushed back the frontiers of what can be created on the lathe.

As with any craft, wood turning demands a strong foundation in the basics: the properties of wood, tools and techniques, and design considerations. Building on this knowledge gives you the ability to express your creativity in a host of challenging ways, from the traditional to the avant-garde.

Spindle turning represents one of the basics that a wood turner should master. Among other things, it improves tool control, which helps with faceplate turning as well. As a professional, full-time wood turner, I structure my teaching around the basics; it gives people a place to start, and it helps me to continue learning in the process. From the Indianapolis Children’s Museum to WoodenBoat School in Maine to the Ontario Wood Show in Canada, I have derived tremendous satisfaction from watching young and old getting hooked on turning. One of my goals as editor of American Woodturner is to provide readers with knowledge of the basics and to entice them with examples of what they could accomplish.

The growing interest in turning is focused primarily on making bowls; new ideas of what bowls and vessels should look like abound. I, too, am fascinated with faceplate turning, as it holds potential for development in years to come. Much of my faceplate work is not functional; the pieces are simply lovely to behold.

As I continue to explore the vast arena of wood turning, I have become more and more aware of the complexity and diversity of the craft. The field is wide open, ready to be explored, and I am happy to be immersed in an exciting and rewarding career.

- Betty Scarpino

Betty Scarpino operates a wood turning studio out of her home in Indianapolis, Indiana. As editor of American Woodturner, Scarpino travels throughout the United States and Canada teaching and demonstrating her wood turning expertise.

The Art of Wood Turning

Wood turning has come of age. Recent years have seen a tremendous increase in the number of people interested in the craft—from hobbyists turning in their basement shop to professionals making a living with their lathes.

Wood turning as an art form began in the 1940s with the likes of Bob Stocksdale, Melvin Lindquist, Rude Osolnik, and James Prestini. Although working independently, they were pursuing the same goals: refined and elegant turned wood objects, whether functional or purely decorative. The 1970s and early ’80s saw a new generation of turners willing to push the boundaries of what was esthetically acceptable and technically possible: Mark Lindquist turning spalted wood and using chain saws to produce sculptural objects; David Ellworth pioneering the use of bent tools to produce thin-walled hollow turnings with incredibly small openings; Bill Hunter carving and sculpting the outside of vessels after the piece was turned.

The American Association of Woodturners, now 15,000 members strong, was formed in 1985. These days, an annual symposium of the AAW provides easy access to information and instruction for anyone interested in the subject. Workshops around the country, as well as books and video tapes, also fulfill the same role.

I have been supporting myself and my family as a full-time wood turner for many years, selling my work through galleries and craft shows, and teaching wood turning throughout the United States and several other countries. Although I teach bowl turning, the work that I do is primarily hollow-turned vessels featuring carved and textured surfaces. They are turned from green wood, with the grain oriented parallel to the axis of the lathe, also known as spindle turning. This provides more stability as the wood dries. I am always after the perfect curve, the fine line, the subtle details.

There are many valid approaches and ways to turn wood, and I would like to offer just three basic rules to help aspiring turners:

1. SHARP TOOLS: Not only are sharp tools much more effective, they make turning a lot more fun! A large percentage of the problems you experience will be directly caused by tools that are not as sharp as they should be.

2. TURN: There is no substitute for time on the lathe. Experience counts.

3. HAVE FUN!—Don’t be so serious that you can’t enjoy the process. Turn just for the joy of turning, improving your skills and making shavings, knowing that you don’t have to produce a finished product every time you turn.

- John Jordan

John Jordan is a professional wood turner from Antioch (Nashville), Tennessee. He has produced several videos on wood turning, and his works are on display in several museums and corporations.

The Appeal of Wood Turning

I turn simply for the love of the creative process. I am addicted to discovery, progress, and the fact that while perfection is forever elusive, yesterday’s challenges often become the basic skills of tomorrow. I love the distinct smell of the various woods, the sound of shavings as they are cut by a sharp tool, and the quickness with which a form emerges from a block of material.

In the past I have enjoyed many other crafts, such as spinning, weaving, and basketry. Each offers its own appeal to the senses: the aroma of spinning fresh wool, the sound of a shuttle, the smell of wet reeds for a basket, and the clicking of knitting needles. Experimenting with turning unusual materials such as bone, plastic, tagua nuts, aluminum, and horn has led to many more interesting sensations for eyes, ears, hands, and nose.

I have been making things for as far back as I can remember, but when I discovered wood turning it became my favorite way to create something. It started when my daughter wanted a doll house. During the process of building, lighting, and furnishing the house, I became interested in the small-scale tools I needed to use. Maybe that fascination came from the fact that my father was once a builder himself.

Several years ago, I designed and began producing a small wood turning lathe, like the one shown in the photograph. My machine has a 5-inch swing and is 12 inches between centers. A wide range of accessories is available including chucks, tools, a threaded jig, and an indexing plate. This was a new beginning for what I like to call “small-scale turning,” and what has developed into an area of its own in the wood turning world, with tools, classes, projects, and even gallery shows.

One of the great virtues of a small lathe is its portability. Many people now take a lathe with them to use at craft fairs, on vacation, or south for the winter. I am able to travel with 10 lathes, tools, and wood in the back of my van to teach classes. There are many school districts that have purchased several small lathes and the necessary tools—all for the price of a large lathe. Shop teachers especially like the quietness of the machine and the fact that many of the small-scale projects may be turned from scraps.

Because wood turning is something I feel strongly about, I have volunteered many hours of teaching turning to kids. I am involved with turning full time and I feel very fortunate that I am able to earn a good income from selling lathes, tools, turnings, and my expertise.

- Bonnie Klein

Bonnie Klein is a wood turner in Renton, Washington. She is featured here turning a spinning top—one of her favorite small-scale production items—on the Klein lathe, which she developed in 1985.

Setting Up

The wood lathe is perhaps the oldest of all woodworking machines. Primitive forms of this tool were used by the Etruscans in the 9th Century B.C. And throughout its long history, the tool has been used in virtually the same way. Somewhat like a potter’s wheel laid on its side, the lathe spins a wood blank while a turner shapes the wood with chisel-like tools. The lathe makes it possible to shape wood into flowing, rounded forms in a way that other tools cannot.

The earliest lathes were human-powered, with a piece of cord wrapped around the blank, connected to a springy sapling and a treadle. With a few modifications, this evolved into the pole lathe popular with British bodgers, who traveled from town to town, working freshly fallen trees into chairs. Flywheels and driveshafts were added to the design, and the lathe emerged as one of the engines behind the mass production of Windsor chairs in the mid-18th Century. Turning became a specialized trade.

With the coming of the Industrial Revolution, heavy-cast engine-powered lathes forever took the elbow grease out of turning. With minor changes, these lathes were essentially the same as those used by modern woodworkers (here). Indeed, many wood turners prefer older lathes to newer ones, refurbishing them and setting them on stands of their own making (here). Woodworkers were beneficiaries of technological advances in machining made during the Industrial Revolution when lathes were adapted to turn metals, as well as wood. This new field brought the wood turner a wide range of chucks and accessories to hold the most delicate and tricky of turned objects, from goblets to lace bobbins.

The chapter that follows is an introduction to the lathe and the tools (here) and accessories (here) needed for turning wood blanks into furniture parts, bowls, and other finished products. Also included in the chapter is a section on safety precautions and equipment (here).

The lathe remains one of the most popular woodworking tools, and wood turning is a craft with an intriguing cachet, like carving or marquetry. It is not hard to understand why: A lathe enables the woodworker to turn something beautiful from nothing more than a stick of wood.

Turning blanks are typically available in short pieces. Some of the more popular examples are shown in the photo above. Resting atop a zebrawood board are samples of tulipwood, kingwood, and ebony. For a selection of the best woods for turning, refer to here.

Turned legs and other furniture parts are shaped on the lathe in a process called spindle turning. In the photo at left, a wood blank is mounted between the lathe’s fixed headstock in the upper left-hand corner and the adjustable tailstock near the center of the photo. The tailstock can slide along the lathe bed to accommodate the workpiece. The blank will be turned into a cylinder and then shaped with a variety of turning tools.

Anatomy of a Lathe

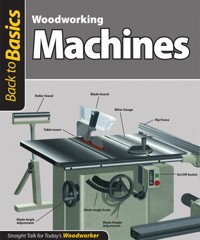

When you choose a lathe, consider carefully the type of turning you will be doing. Some models are made specifically for faceplate turning, in which the blank is secured only on the head-stock. Others are small enough to rest on a benchtop. The lathe shown below is a typical freestanding model used for both spindle and faceplate turning.

Lathe size is measured in two ways: swing and capacity. Swing is twice the distance between the headstock spindle and the bed, which limits the diameter of blanks. Capacity is the distance between the headstock and tailstock, which limits the length of blanks. The weight of the lathe is important, as greater weight provides stability and dampens vibration. Another feature to consider is how easy it is to change speeds; larger workpieces must be turned at lower speeds than smaller ones. Changing the speed of some lathes involves switching a drive belt between two sets of stepped pulleys; other models have variable-speed pulley systems that allow the speed to be changed without switching off the tool.

If you decide to buy a used lathe, check the motor, bearings, spindle threads, and lathe bed for wear. Make sure the tool rest and tailstock run smoothly and all locking levers work. Also make sure that the spindle thread is standard; if not, chucks and other accessories must be rethreaded to fit.

Headstock Assembly

Drive Assembly

The 1950s-vintage Wadkin Bursgreen lathe is prized for its machining capacities and innovative features, such as a brake that stops spinning blanks quickly and a removable bed segment near the headstock to accommodate large-diameter faceplate work.

Tool Rests and Lathe Stands

A tool rest acts as a fulcrum for your turning tools, providing a fixed, horizontal weight-bearing surface for balancing and bracing a tool as you cut into a spinning blank. The tool rest on a lathe is made up of two parts: a tool base and the detachable rest itself. The base can slide along the length of the lathe bed, according to the needs of the work. The tool rest mounts in the base; the height and angle of the rest are adjustable so it can be positioned parallel to the lathe bed for spindle and faceplate work, perpendicular to the bed for faceplate work, or at an angle in between. In addition, the base and rest can be mounted on an outboard bed for large-diameter faceplate turning. There are a number of different tool rests for specialized turning tasks; a selection is shown below.

Shop Tip

Weighing down a lathe

Because turning wood can cause a great deal of vibration, a lathe needs to be as stable as possible. Even the best lathe is an inefficient and dangerous machine if it is not weighed down properly. Because most modern lathe stands are made of lightweight steel, it is necessary to weigh them down with cement blocks or sacks filled with sand, as shown here, to reduce vibration and noise. Bolting the lathe to your workshop floor is another option.

Tool Rests

Standard tool baseSlides along the lathe bed; features a fitting for tool rest shaft. A lever-operated cam mechanism locks base in position on the bed. Base shown is the type that comes with most lathes.

Tall tool baseUsed on lathes with lower outboard beds for turning large faceplate work, this base is 4 inches taller than standard bases; a lever-operated cam mechanism is used to lock the base in position.

Standard tool restMounts in tool base for general faceplate and spindle work; comes with lathe.

Short restUsed for smaller spindle and faceplate work; typically 6 inches long.

Long restMounted in two standard tool bases for long spindle work; available in 18- and 24-inch lengths.

S-shaped bowl restUsed for turning the outside and inside of bowls.

Right-angle restMounted in standard tool rest to turn bowl blanks; long side is positioned perpendicular to lathe bed to turn face of bowl, while short side is positioned parallel to lathe bed to work sides. Long side typically measures 7 inches.

Dressing a Tool Rest

Smoothing a worn tool restBecause a tool rest is made of softer steel than the steel used for turning tools, it will eventually develop low spots, marks, and nicks. If not remedied, these imperfections will be transferred to the blanks you turn, or make the tool you are holding skip and possibly cause an accident. You can dress a tool rest easily with a single-cut bastard mill file. Holding the file in both hands at an angle to the rest, push it across the top surface. Make a series of overlapping strokes until you remove all the nicks and hollows from the rest, then smooth the surface with 200-grit sandpaper or emery cloth followed by a light application of floor wax, buffed smooth.

Shop Tip

Adjusting lathe height

The height of a lathe is crucial to efficient turning. Commercial lathe stands are often too low, which can make it difficult to control your turning tools. You also may tire more as a result. As a rule of thumb, the height of a lathe’s spindles should be level with your elbows. If necessary, you can raise your lathe to the proper height by bolting it to solid blocks of dense hardwood with foam rubber glued to their undersides.

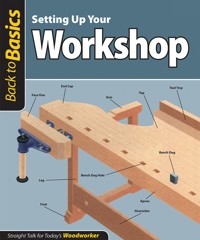

A Lathe Stand

Older lathes are prized by wood turners because they were often built better than newer models. The only problem is that these vintage lathes often lack a stand or a working motor. Fortunately, it is easy to equip a lathe with both. Lathes need less powerful motors than most stationary machines. A ½-hp model that runs at 1725 RPM—half the speed of a table saw motor—will do.

A lathe stand needs to be heavy and solid, like the rugged shop-built version shown below, constructed primarily from 2-by-6s. The motor is mounted behind the lathe, with the pulleys under a safety guard. The stand also features a wooden tension pedal that allows you to release belt tension and stop the spindle instantly. Refer to the illustration for suggested dimensions.

For the stand, start by cutting the legs to length from four 2-by-6s, then saw a triangular notch from the bottom of each leg to make feet. Join each pair of legs with two crosspieces, locating one crosspiece just above the feet and the other 1½ inches from the top of the legs. Cut the shelf from two 2-by-6s, and screw the pieces to the lower leg crosspieces.

Next, install the top, cut from two 2-by-6s and a piece of ¾-inch plywood. Screw the boards and two braces to the upper leg crosspieces, then fasten the plywood to the 2-by-6s, as shown above. Bolt the lathe to the top of the stand.

Screw the motor to a mounting board cut from ¾-inch plywood. Then fasten the board to the top with butt hinges so the steps in the motor pulley are in line with the headstock pulley steps. Mount the drive belt on the pulleys.