5,12 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

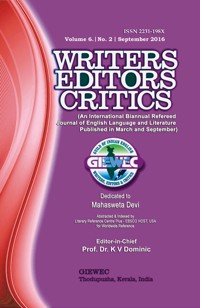

Writers Editors Critics (WEC) An International Biannual Refereed Journal of English Language and Literature

Volume 6 Number 2 (September 2016)

ISSN: 2231-198X

Special Issue: a tribute to Indian poet Mahasweta Devi (14 January 1926 - 28 July 2016)

- A Poetic Tribute to Mahasweta Devi - K. V. Dominic

- Mahasweta Devi: Death cannot Claim a Valiant Soul - Ketaki Datta

- Mahasweta Devi: Fourth World Literature for Indigenous People--An Obituary - Ratan Bhattacharjee

- Charting the 'Subaltern' Terrain--The Outsider-Insider: Mahashweta Devi's "Pterodactyl" in Perspective - Poonam Sahay Aarti to Maha Shakthi - P. Gopichand & P. Nagasuseela

- Mahasweta Devi: Voice of the Deprived Millions - Manas Bakshi

- The Mourners of Mahasweta Devi: A Critical Analysis of Rudali - J. Pamela

- The Subaltern Woman and Woman as Subaltern: A Study of 34 Selected Works of Mahasweta Devi - Anisha Ghosh (Paul)

- A Critical Analysis of Mahasweta Devi's "Bharsaa" - Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

- The Plight of Tribal People in Mahasweta Devi's "Shishu" (Children)

Writers Editors Critics (WEC) is a research journal in English literature published from Thodupuzha, Kerala, India. It is the main product of Guild of Indian English Writers, Editors and Critics (GIEWEC), a non-profit registered society of Indian English writers, English language professors as well as PhD research scholars. The publisher is hence GIEWEC itself and editor is its secretary Prof. Dr. K. V. Dominic, a renowned English language poet, critic, short story writer and editor who has to his credit 27 books. It is truly a refereed journal which has got a screening committee consisting of eminent professors. The articles are sent first to the referees by the editor and only if they accept, the papers will be published. The journal is international in the sense each issue will have contributors from outside India.

The singularity or specialty of this journal is that it has no thrust area. It is hence so accommodative that it publishes papers on all types of literatures including translations from regional languages, literary theories, communicative English, ELT, linguistics etc. In addition, each issue will be rich with poems, short stories, review articles, book reviews, interviews, general essays etc. under separate sections. WEC has print version as well as kindle version.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 316

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Writers Editors Critics (WEC)

Estd. March 2011

(An International Biannual Refereed Journal of English Language and Literature Published in March and September)

Volume 6 Number 2 (September 2016)

ISSN: 2231 – 198X

(Abstracted and indexed by Literary Reference Centre, EBSCO Host Publishing, USA for Worldwide Reference)

Board of Editors

Prof. T. V. Reddy

Prof. Rajkamal ShiromaniDr. Jaydeep SarangiDr. Lata Mishra

Review Editors

Dr. Patricia PrimeDr. S. Ayyappa RajaDr. Sugandha AgarwalProf. Kavitha GopalakrishnanDr. S. BarathiMs. Anisha Ghosh Paul

Associate Editors

Dr. S. KumaranDr. Ketaki DattaDr. Joji John Panicker

Editor-in-Chief

Prof. Dr. K. V. Dominic

Published By

Guild of Indian English Writers, Editors and Critics (GIEWEC)

Reg. No. I - 194/2010, XXI/439, Thodupuzha East,Kerala, India – 685585Email: [email protected],Web Site: www.profkvdominic.com

Guild of Indian English Writers, Editors and Critics (GIEWEC) pays its tearful tribute to

Mahasweta Devi

(14 January 1926 – 28 July 2016)

(One of the greatest Indian writers who lived and wrote for the marginalized, tribals and dalits)

CONTENTS

A Poetic Tribute to Mahasweta Devi

- K. V. Dominic

PAPERS AND POEM ON MAHASWETA DEVI

Mahasweta Devi: Death cannot Claim a Valiant Soul

- Ketaki Datta

Mahasweta Devi: Fourth World Literature for Indigenous People—An Obituary

- Ratan Bhattacharjee

Charting the ‘Subaltern’ Terrain—The Outsider-Insider: Mahashweta Devi’s “Pterodactyl” in Perspective

- Poonam Sahay

Aarti to Maha Shakthi

- P. Gopichand & P. Nagasuseela

Mahasweta Devi: Voice of the Deprived Millions

- Manas Bakshi

The Mourners of Mahasweta Devi: A Critical Analysis of Rudali

- J. Pamela

The Subaltern Woman and Woman as Subaltern: A Study of Selected Works of Mahasweta Devi

- Anisha Ghosh (Paul)

A Critical Analysis of Mahasweta Devi’s “Bharsaa”

- Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

The Plight of Tribal People in Mahasweta Devi’s “Shishu” (Children)

- P. Senthilkumaran & S. Kumaran

Mahasweta Devi: An Unending Legend (an Obituary)

- Reema Das

CRITICAL/RESEARCH ARTICLES

K. V. Dominic’s Winged Reason: A Portrait of Social Realism

- D. C. Chambial

Italian Women’s Archives: Their Origin, Development, and American Connections

- Elisabetta Marino

Chetan Bhagat’s Fiction: A Clarion Call for Restructuring the Canon of Indian Fictional Writing

- Kavitha Gopalakrishnan

Playing God: Robin Cook’s ‘Mutation’ as a Reworking of the Frankenstein Theme of the Creator Pitted against the Creation

- Lekshmi R. Nair

Quest for Identity and Female Iconoclasm in Jhumpa Lahiri’s TheLowland

- Mohd Faiez

History Community and Identity: Reading M. G. Vassanji’s TheMagic of Saida

- Siddhartha Singh

The State of Emergency and the Loss of Identity in Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance

- A. Sulochana & S. Kumaran

Shakespeare’s Conception of Insomnia and Somnambulism in Macbeth

- Deen Dayal

REVIEW ARTICLES

A Philosophic Voyage through K. V. Dominic’s Poetry

- S. Barathi

The Circle of Life: A Critical Evaluation of Chandramoni Narayanaswamy’s Houseful.

- Kavitha Gopalakrishnan

BOOK REVIEWS

T. V. Reddy’s A Critical Survey of Indo-English Poetry

- K. V. Dominic

I. K. Sharma’s A Treasure Island of Letters

- Kavitha Gopalakrishnan

Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya’s Write My Son, Write—Text and Interpretation: An Exercise in Close Reading

- S. Barathi

T. V. Reddy’s Thousand Haiku Pearls

- Patricia Prime

S. Kumaran’s (ed) Philosophical Musings for a Meaningful Life: An Analysis of K. V. Dominic’s Poems

- Elisabetta Marino

Dr. Molly Joseph’s Autumn Leaves

- Sugandha Agarwal

SHORT STORIES

Niyog—the Authorization

- Ramesh K. Srivastava

Strange Equation

- Manas Bakshi

An Elephantine Memory

- Chandramoni Narayanaswamy

Guilty Conscience

- Jayanti M. Dalal (Trans. Himmatsingh Waghela)

POETRY

What a Justice!

- D. C. Chambial

Woman is a Woman

- D. C. Chambial

Blue Bells

- D. C. Chambial

Pain and Laughter

- D. C. Chambial

Rivers of Happiness

- D. C. Chambial

Unseen Hands

- Manas Bakshi

Changing Fate

- Manas Bakshi

Where was the Sun?

- Jayanti M. Dalal (Trans. Pavankumar Jain)

They Decide

- O. P. Arora

Peace

- O. P. Arora

Union

- Sibasis Jana

Rhythms of Clouds

- Sibasis Jana

Lines

- Molly Joseph

Dream-call

- Ram Sharma

Ganga Maiyya

- Ram Sharma

Morning

- Ram Sharma

O! God Who Are Thou

- Ram Sharma

O Globetrotter

- Sugandha Agarwal

Ideology

- Vijay Kumar Roy

The Earth Orbits

- Parthajit Ghosh

List of Contributors

Brouchure of GIWEC’s Collaborative Litterary Festival at AKC College Guntur

A Poetic Tribute to Mahasweta Devi

K. V. Dominic

Mahasweta Devi literally means Goddess Saraswati

Her mother’s name Dharitri meaning Earth

Yes, Mahasweta Devi who departed us on 28th July

was Saraswati to millions of tribals, dalits and marginalized

who were lifted from doom and darkness to resurgent light

She was indeed proud daughter of Mother Earth

committed to protect Earth and her inhabitants

from all kinds of exploitations and maternal assaults

Didi, you were the loving compassionate sister as well as

mother of the millions of helpless miserable fellow beings

Even at ninety you were eager to fly to wipe out tears

You could hear the scream of tortured people and

neither health nor distance could stop your incessant flights

Didi, you were the crusader of the downtrodden,

tribals, dalits, women, landless, migrants, prostitutes

You were savior of denotified tribes Lodha and Shabar

You were their mouthpiece—spoke for them, raised funds for them

legally fought for them, and organized them to fight for their rights

Didi, you are role model to all writers in the world

Unlike others writing from mansions full of luxury

and shedding crocodile tears at the plight of the poor

you lived among them, ate from their plates and

braved all dangers supporting their noble survival cause

Gandhi and Mother Teresa influenced you a lot

Practised in your life what you wrote and preached

And your social life and literary life merged into one

Your writings created an Everest in literary world

More than hundred novels and over twenty books

of short fiction all dealing with human sufferings

And your priority was for content than to form

Didi, you wanted to work for ever for your people

And hence told “I don’t want to die. I want to live forever.”

Only your body has departed and your spirit remains immortal

And like the mahuva tree which grows on your grave,

the values and messages you have sown in the minds

will germinate and spread all over the world and

bower aching minds from terrible burning issues

PAPERS AND POEM ON MAHASWETA DEVI

Mahasweta Devi: Death cannot claim a Valiant Soul

Ketaki Datta

Mahasweta Devi’s death came as a blow at the point of time when the whole world was being rocked by incendiaries and violent acts of terror. I am an avid reader of Mahasweta Devi’s works, not for her bare style and scintillating vocabulary, but for the underlying responsibility of making the youths aware of their existence on this earth. The youths cannot remain zombie by reading her works, they feel like working for all around them, for leaving a better universe for tomorrow! And, my own reaction on hearing the news of her abrupt demise was a journey to the days in the past, when I was dealing with “Mother of 1084” as a college text and asking the students to feel the plight of Brati’s mother, who was a bereaved mother of a dead son, bearing the identifying number: 1-0-8-4. The whole class fell silent when the corpse of the mother’s son, who died during Naxalite uprising, in the ‘70s, waited to be identified by his mother. Being a teacher, delving deep into the sad event and taking it as an issue to be judged in the light of critical theory was next to impossible for me. I shed tears, not always silently, and my students shared my grief by falling silent for some moments. No doubt, literature has a certain power to stir the inmost feelings, but, the work that weds fact to fiction has a strength of its own, that can hardly be gainsaid.

Mahasweta Devi is a name of a movement, which never ends, never will end. The tribals of Purulia lost their ‘mother’ on the day when the writer-activist-humanist breathed her last. Such a soul cannot breathe her last, such a messiah cannot have an end. Jesus, in the garden of Gethsemane had an inkling of his imminent crucifixion and Mahasweta Devi had an inkling of a universe being crisscrossed by valueless strife and altercations, violence and bloodshed, betrayal and apocalypse. Christ had resurrected himself and Mahasweta would resurrect herself through the conscience of each individual of modern times, who feel her absence within and gets a spur to go out on a mission to change the society.

The genius of all times, started off her writing career with the tale of Rani of Jhansi. And, even she had to take a stint of an English teacher for a length of time too. But her real call came when she began to pay visits to Purulia where the tribal people—Khedia and Shabar found a ‘mother’ in her. We, the so-called sophisticated arm-chair thinkers, cannot even imagine in our wildest dreams how Mahasweta Devi used to pay regular visits to the illiterate, un-reclaimed populace, who needed an exposure to the wider world. And, Mahasweta Devi came to their aid.

After short stint as a teacher of English in a local school, Mahasweta Devi devoted her life to writing fiction and fighting for the cause of the downtrodden. In the stories like “Stanadayini” [The Breast-Feeder] and “Draupadi”, the plight of women, especially those belonging to the lower rung of the society, come to the fore. Gayatri Chakraborty Spivak translated these stories and felt as though the bare style, the powerful, un-ornamental diction, direct and straight approach to the problem the women face usually, are natural attributes of the stories, bearing stamp of a compassionate heart, weeping within.

Aranyer Adhikaar, Rudaali are just a few novels which had been filmed by eminent directors, as Hazaar Chaurasi ki Maa. The voice of the have-nots, the hoi polloi got heard through her mighty pen. The wails of Draupadi, the suppressed sobs of Brati’s mother, the professional breast-beating cries of the professional crying women–all speak of the struggle of the women who were treated shabbily, since aeons.

The recipient of Sahitya Akademi Award, Jnanpith Award, Ramon Magsaysay Award and Padma Vibhushan never stood aloof from the ordinary men, the individuals who mattered the most to bring viable changes in the society. The present writer, too, had several chances to run into the gracious writer/activist in numerous programmes, either at Bangla Academy or Jibananda Sabhagriha or Rabindra Sadan. Everywhere she greeted this present writer with a smile saying, “. . . Just teaching in a college will not do. Come, stand beside those who have no spokesperson to tell their stories to the people who matter.” This writer used to smile back and nod in the affirmative but never took any initiative to that end save teaching one or two poor students free of charge at her residence. The remarkable progress in tribal education, improvement in the lifestyle of the tribals, financial grants for the tribal children who come out with flying colours in different board examinations—all owe to incessant efforts she had put in, to better their deplorable plight. Such was the enlightened lady, who thought of her ‘children’ before all. Nabarun was her own son, but she had even million sons apart from her own. Mahasweta Devi, the wife of Bijon Bhattacharya [her first husband], hailed from a family of talents. Ritwik Ghatak, the renowned filmmaker was her relative, Bijon Bhattacharya created stir in the theatrical scene of Bengal by writing his epoch-making play, Nabanna. Hunger, poverty can change a person to a strange one, Buddhadev Dasgupta, in his film of the eighties, Neem Annapurna had also pointed that out.

But topping all, the depiction of Sujata, Brati’s mother in the film Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maa stands nonpareil. The turbulent times of the seventies had been brilliantly, rather flawlessly portrayed by Govind Nihalani on the screen. The present writer feels tempted to dwell on this novel, which had been translated brilliantly by Samik Bandyopadhyay in the form of a play and it served as the basic text for Nihalani. While this present writer had been asked to contribute to the prestigious volume on “Naxalites in Cinema” by Prof. Pradip Basu, an eminent academic [presently Professor of Political Science, Presidency University, Kolkata], who rose like a phoenix from his ‘Naxalite’ past, she could not but think of contributing on “Mother of 1084” as a document of the turbulent times—the seventies.

Being mother of Brati, it is really surprising when, Sujata confesses at last that she knew her son hardly! She knew not her son, inside out! She was madly fond of her son, even though, the family with materialistic demands and aristocratic background was absolutely nonchalant to the presence of her youngest son in the cocoon of their household itself. Brati proved himself rebellious of the ideals of this family, by joining a group of young adults who felt deprived, outcast, who had only dreams galore in front of their eyes, like the surging tides of the sea. They dreamt of ushering liberation of thoughts, of ideals, of the political framework of the nation, of everything and all. It was the decade of LIBERATION, as the appellation ran. But, in reality, these rebellious youths were hounded out of this state, were butchered, were stamped as anti-socials. Brati, just a day before his birthday, on the sixteenth of January that year, had gone to Somu’s place, where in the dark of the night all these brats were called out by a group of boys who opposed their ideals and had been brutally hacked to death. Somu’s father, running amuck, seeking justice from pillar to post, died immediately after, leaving the family in the lurch.

As the story ran, Sujata, a bank-employee, went from one acquaintance of her dead son to the other, for sharing the inconsolable grief, in search of solace. But at the end of the day, she came back home for her daughter’s engagement, and finding all pretences reaching their heights in the so-called elite social circle, she felt lonely, absolutely cooped up in her own world with the threadbare remembrances of her dead son, Brati, all around. The picture of the sham and pretension has been faithfully etched by Mahasweta Devi. Saroj Pal, the cop, who refuses to hand the corpse of 1084 to Sujata came to Tuli’s engagement on invitation, though he dared not come upstairs to avoid direct interaction with the mother of corpse No. 1084, to whom he had been harsh and irascible. He congratulated the newly-engaged couple, however. After all, HE HAD BEEN ON DUTY!!! Dibyanath, who loathed the ways of his son’s life, kept pining for him in front of all, feigning as if he were the best father, and Brati, the best son of this world. Though he had to hush up his ‘unruly’ son’s case, though he had to take all possible care to see his son’s name not figuring in the eminent dailies! All pretence, all sham! It was only Hem, the maid, who kept weeping all day long, silently, as on this day, Brati’s existence had been snuffed out from the face of earth! It was only Sujata, the mother, who kept dropping by at the places of Brati’s friends and dear ones, sharing memories of that ill-fated day when her son’s existence stood nullified, just as they suffered the same lot, losing their dearest one, perhaps the only breadwinner of their family. Sujata re-explored her dead son in their company, in Somu’s room, in Nandini’s place, where Brati used to whisper words of endearment in her ears. Back home, while the merrymaking was on, she saw Brati in a blue shirt, getting ready to leave, halting a while beneath the stairs, throwing a long look at her! Sujata fell on the ground, her appendix being suspected to be burst! It is not stated by the author whether she came home after the surgery or succumbed to the long-nursed vermiform appendix that turned sore!

When the novel had first come out in a Bengali journal, Prasad, it moved all and sundry to tears, though detractors called it ‘sob-stuff’. Nihalani has done his job well, save the display of a serene ambience in the last scene, where Dibyanath shared mirth with his family and friends, while Sujata’s musings kept running on the screen in the background, though her ‘oneness’ with her dead son seemed in no way interrupted, rather went parallel to the din and bustle of the party, that was on!

The film had won rave reviews, had won many a heart. But I feel like losing a ‘mother’, who was not a mother of only one thousand and eighty four, but millions and millions of sons and daughters, who, loved her, revered her as their mentor, loved one and a pillar of strength!! Who says she has ‘passed away’? She is there with us, at the crack of dawn, in the serenity of gloaming, in the stillness of the night!!

References

Datta, Ketaki. “‘Hazaar Chaurasi ki Maa’: A Faithful Document of the Turbulent Times on the Silver Screen” in Pradip Basu, ed. Red on Silver: Naxalites in Cinema, Setu Prakashani, Kolkata, 2012.

Devi, Mahasweta, Mother of 1084, Trans. Samik Bandyopadhyay, Seagull Books, Kolkata, 1997.

Mahasweta Devi: Fourth World Literature for Indigenous People—An Obituary

Ratan Bhattacharjee

The fourth world covers all ethnic, racial, caste, linguistic, gender, even socio-political and economic marginal. Many universities including Srimata Vaishno Devi University are coming up with International Conferences on Fourth World Literature for deliberation on the prospects and challenges. Earlier Pune Higher Education Research Society organised conferences on fourth world literature. In India among the writers who wrote for the people of the Fourth World the name of Mahasweta Devi comes first and foremost. She had a long six-decade long writing career and her heart bleeds in her golden inking for the marginalised people, subalterns and the Dalits of the un-notified areas of Indian hilly region. Mahasweta Devi never changed her writing table and not the style of her writing too as she lived all her life to depict the sorrows of life and anguished existence of the oppressed sections of society, sometimes the Kurmi, Dusad or Bhangira of Bihar and Madhya Pradesh or sometimes the Santals of Bengal. On the one hand she brought Jim Corbett Lu Xun Verrier Elwin in translation. For her writings on the indigenous people she is now regarded as one of the earliest writers of Fourth World Literature which emerges as a powerful literary front after Post Colonial literature.

In 1967, Mbuto Milando while in a conversation with George Manuel of Canada used the term, ‘fourth world’ and defined it: “When native people come into their own on the basis of their own cultures and traditions, that will be the fourth world. The horizons earmarked are much larger and it is inclusive of the larger sections of the marginalized including the refugees and immigrants or transgender peoples of the world besides the native and the aborigines. Thus the fourth world as an Indian reality is envisaged. It is not a challenge against the third or the first world, but a protest against an age old attitude ingrained in the society about the marginalized of the fourth world. With the advent of globalization, it would be a blunder to drag all the oppressed sections under the same portmanteau term. Even feminism has multiple offshoots nowadays. Given the above deliberation of the indigenous nations one could now say that women are ‘triply colonized’ (to take humble liberty with Gayatri Spivak’s term doubly colonized). Besides literature and culture, deliberation can occur upon the other aspects of the fourth world which demand some attention from the disciplines like Cultural Studies, Ethnic Studies, Black Studies, Dalit and Tribal Studies, Women’s Studies, Queer Studies, Post-colonial Studies, Class Relations, Economics, International Relations, Anthropology, Area Studies, Sociology, Linguistics etc. Even in the First world this sub population can live but with the living standards of those of the third world and below that. Deliberate marginalization of the sub population in a state is discussed which has made the malady worse. The non-recognition and exclusion of the vast populace, Romani People, Sami, Assyrian, Kurds, and other indigenous of the first nations are to be included in the fourth world. Aboriginal Australians, Native Hawaiians, Maori of New Zealand or the Jaroas of Andamans should be given their own room in literature.

In Mahasweta Devi’s writings too, it is thus ‘re-christening of literature’ after post colonialism. Her writings reflect a shift towards a new literature which is a quest for a new space in literature for the marginalised and it gains a new momentum with novels like Mother of 1084. The laxmanrekha of literature created by the non–marginalised and by the privileged class is to be crossed globally in literature. It is like a deconstruction of the third and first world narratives which smother differences and plurality. Thus the traditional myths of literature are demolished in the perpetual engagement of the researchers in the quest for a space of the Marginalised and Mahasweta Devi emerged as the doyen of dalit literature in nearly all her writings.

She was an eminent litterateur and as a zealous activist she reached beyond the Third World life of poverty and oppression in the society to voice a loud protest against the upper caste dominated social hierarchy. Mahasweta Devi was a leftist Bengali middle class intellectual in the fifties and she herself describes the motif of her writing in “Draupadi”: “Life is not mathematics and the human being is not made for the sake of politics.” She loudly protested against all forms of social injustice even against people living in the plains such as Singur and Nandigram.

She took her creativity beyond mere writing as her heart in real bleeds for the tribal, the downtrodden, the have-nots, the deprived and the oppressed ones wherever they lived on this planet. She used her golden pen to scribble the bronze stories of barren plains that lead to no bright dawn of a new millennium. In the 6o-year long career as a writer, she penned more than one hundred novels, twenty collection of short stories and authored innumerable articles nearly all on tribal life.

Mahasweta Devi’s novels and short stories are a marvel for readers and researchers all over India, nay the world as they comprise a large chunk in postcolonial literature. Unlike many writers living in the ivory tower, she led an exemplary life of an activist and gave vent to her personal conviction and writings without ever for a single moment wavering from her firm faith. Her masterpiece was written in 1998—the Mother of 1084. It was screened and it may be called the most remarkable political novel in which we see the portrayal of a mother from a psychological point of view which is given a new dimension. She wanted to know the reasons behind her son’s participation in the Naxalite movement. This novel was inspired by Maxim Gorky’s Mother and the backdrop is that of a revolutionary background though on a much smaller scale compared to the Russian Revolution. Her other novels and short fiction too offer precious insights into the lives of the oppressed class.

She was awarded Padma Vibushan, Magsaysay, Sahitya Akademi and Jnanpith for the wonderful sagas of pains and poverty that she narrated in Hajar Churashir Ma (Mother of 1084, Aranyer Adhikar, (Right to Forest), Jhansir Rani (The Queen of Jhansi) Agnigarbha (The Fire Within), Rudali, Sidhu Kanhur Daaakey. These offer precious insights into the lives of the oppressed class. Her novels were adapted for silver screen. In 1993 the first award winning film Rudaali directed by Kalpana Lajmi was based on her novel of the same title where the sad life of the professional mourners of Rajasthan is focused with ironical commentary on the upper caste life of the males. Italian director Italo Spinelli also made the multi-lingual Gangor based on her short fiction “Choli Ke Peeche” about the female emancipation. The famous song ‘Choli ke peeche’ might have been inspired by this story. The culture of mothers, cow-mothers, nation-mothers, and goddesses embodying motherhood was not what Mahasweta Devi envisaged in her life and writing. Chotti Munda and His Arrow, Bashai Tudu, Breast Stories, Titu Mir—all give us hope and courage.

She was an activist going beyond her writings like the revolutionary poets of Latin America. Like Arundhati Roy, she too actively voiced her protest against oppression of any kind and man’s exploitation of nature for urbanisation. She founded many grass-root level societies and did a lot of campaign for the welfare of the tribals of Bengal, nay India. All these real first hand experiences were recorded by her in her fiction and articles.

The 91 year old Mahasweta Devi who is no more is justly described as the ‘conscience keeper’ or a ‘voice of justice and equality’ as she used the creative tool for being with the marginalised of the marginalised and the indigenous people fighting for their rights. Probably this is how she pioneered unconsciously the fourth world literature in India. Even as an academician too she used to write for the Marginalised section of people but mostly for the newspapers and journals. Her creative writings finally brought her the real recognition. The world depicted by Mahasweta Devi includes a whole range of the tribal and peasant societies that share a number of attributes, including a low level of political and economic integration in the state system, an inferior political status, and an underprivileged economic position. These dwellers of the fourth world may virtually stay in the third world but cannot afford the access even to the third world standards of living.

Gayatri Spivak translated her story “Draupadi.” Spivak wrote in the Preface to focus on the Senanayak: “author’s careful presentation of Senanayak as a pluralist aesthete. In theory, Senanayak can identify with the enemy. But pluralist aesthetes of the First World are, willy-nilly, participants in the production of an exploitative society.” Draupadi is the most celebrated heroine of the Indian epic Mahabharata. It is the name of the central character. She is introduced to the reader between two uniforms and between two versions of her name: Dopdi and Draupadi. It is either that as a tribal she cannot pronounce her own Sanskrit name (Draupadi), or the tribalized form, Dopdi, is the proper name of the ancient Draupadi. She is on a list of wanted persons, yet her name is not on the list of appropriate names for the tribal women. This is how Mahasweta Devi scribbled and her golden pen beautifully reaches out to the poor and the suffering people.

Charting the ‘Subaltern’ Terrain—The Outsider-Insider: Mahashweta Devi’s “Pterodactyl” in Perspective

Poonam Sahay

Abstract: This research paper seeks to highlight the neglected and ‘sidelined’ aspects of the tribal lives, their myriad experiences, songs and rituals in Mahashweta Devi’s “Pterodactyl”. The writer provides a voice to the tribals, their subaltern preoccupations, justifying their collective, militant and violent resistance at times, when they feel their efforts are wasted, bearing no fruit whatsoever. Her message to the society is very clear warning the people to either change their callous attitude or be ready for a full-throated revolt. Thus, Mahashweta Devi devotes herself fully to exposing the various faces of exploiting agencies, raising tribal and non-tribal issues of vital importance. “Pterodactyl” embodies all these beautifully.

Keywords: pterodactyl, subaltern, tribals, dalits, adivasi, khajra

Introduction

“Mahashweta Devi wonderfully illustrated the might of the pen. A voice of compassion, equality and justice, she leaves us deeply saddened. RIP”

—Narendra Modi @narendramodi, July, 28, 2016.

The words of our esteemed Prime Minister ring true far and wide. Wife of one of Bengal’s most prolific playwrights and litterateurs, Bijon Bhattacharya, the activist-writer grew up in the family of Bengal’s leading writers, poets and filmmakers. Filmmaker Ritwick Ghatak was her uncle. Influenced by the Communist movement of the 1940s, Mahashweta Devi chose to work among the poorest of the poor in the tribal areas of southern West Bengal and in other parts of the country. “There are very few writers who are capable of narrating – directly – what they experience. She (Mahashweta Devi) is one such writer who routinely described what she witnessed,” according to Ms. Joya Mitra, a prominent writer and a close associate of Mahashweta Devi. “And the people whom she came across in real life slowly made their place in her stories and novels.” Apropos Mahashweta Devi herself: “All my writing is about real people and real issues. It doesn’t cater to any specific ideology.”

Discussion

However, Devi never espoused violent methods of challenging the State. She never endorsed the use of violence as it disrupted the lives of adivasi villagers, who, she said, were becoming collateral damage in the war between the extremists and the State. Her novel Hazar ChaurashirMa on the Naxalite Movement in West Bengal, was, in fact, about the struggle of a Naxalite, who is killed by the police, goes through as she grapples with the knowledge of his secret life as a revolutionary. The novel is a projection of her own son Nabarun Bhattacharya’s ideological leanings towards the Leftist movement, according to Samik Bandyopadhyay. Both mother and son had a bitter separation later in life.

Only ten per cent of Devi’s novels have been translated into English from the original Bengali. Devi’s literary career reached its first major milestone in 1956 when she published Jhansir Rani, a historical fiction on the life of Rani Lakshmibai. “This work coincided with the release of a centenary history book on the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny commissioned by Jawaharlal Nehru to the Calcutta-based historian S. N. Sen.” Says Samik Bandyopadhyaya.

Writing was not merely a passion, but an instrument of change for the great writer. Though they may seem different, arts and activism are not different domains altogether. The quest for roots in the postcolonial age depicts a unique mixture of art and activism or literature and politics in the works of many contemporary writers, like Ngugi wa Thiong’o, James Baldwin and Ken Saro-Wiwa. Mahashweta traverses the world of fiction, history, journalism, sociopolitical activism with equal comfort and mastery. Her literary work is fired by the zeal of her activism, journalistic skills, honed over a certain period as also her humanitarian concerns. One may be surprised to note that the writer did not hesitate in travelling miles into the remote regions of tribal India just to gain an insight into the harsh realities of the indigenous masses. It is because of this that the core issues of the tribals became translated into the literature she wrote. Her active participation in the liberation of the movements of the so-called ‘criminal tribes’ as also the tribes of West Bengal, Bihar, Chotanagpur region and Madhya Pradesh is significant. Her writing reflects the utter nastiness and banal desolation of the tribal people. She also indicts the Indian society for the indignity and indecency heaped on these oppressed sections of society. She felt that they are always ‘sidelined’ from the mainstream and so she discussed their history and culture, highlighting its richness and variety enthusiastically. She did not fail in criticizing the government for purchasing agricultural fertile land from farmers and then selling these lands to the great industrialists at a cheaper rate. The commercialization of Santiniketan, set up by Rabindranath Tagore did not escape her ire too. The Budhan theatre of Tribals in Gujarat received a thumping support from her always.

Art and Cultural critic Sadanand Menon notes that Mahashweta Devi had a profound influence on the thoughts of the people who came in her contact. “Reading her novel Arnyer Adhikar had a deep influence on me and made me aware of the exploitation of the natural resource to the disadvantage of the tribal people,” he said. Mahashweta Devi was not an ivory-tower writer but one who engaged with the harsh realities of society. However, she was different from many other writers, in the sense that she showed the people how to address such challenges as well. “And though the writer is no more in the corporeal sense, her words, her thoughts, and the lives of those she touched infused subaltern writing with a tangible value and will ensure she continues to live on in our midst.

Mahashweta Devi’s story “Pterodactyl, Puran Sahay and Pirtha” (1995) analyses the cultural and environmental issues of the tribal people in modern India effectively. She uses myth skillfully and invests it with the credibility of a tribal cause. The story of Pterodactyl is quite important and hints suggestively. The pterodactyl of the story, an extinct creature is resurrected and brought back. It is used to emphasise the importance of the ancient tribal ways of life because Devi’s focus is on the hazards of modernity and its impact on the natural and simple lives of the poor tribals. A vivid presentation is made of the entire community, their rituals, history and culture. The tribal world is shown as a continent, dominated by the mainstream people. However, instead of exploring and knowing about the tribals, the mainstream people try their very best to disrupt their very existence. All this is done in an extremely selfish manner to serve their own interests. This story is part of “Imaginary Maps” translated by Gayatri C Spivak. Incidentally, Mahashweta Devi’s encounter with the rock painting and Pithora, painted by her adivasi friend from Tejgadh inspired her to use the myth of the pterodactyl. The painting seemed to echo the ancient tribal lores, whereas the modern forces did nothing but to destroy this timeless piece of art. The sense of loss pervades the entire story. Shankar is an educated tribal who reflects on the plentiful past of the tribals. In ancient days, consent of Mother Earth was necessary and sought by the tribals before constructing anything. They maintained the sanctity of the land and never thought of destroying it. However, outsiders come and violate the rules of the land. They are depicted as “white ants fly in teeming swarms before the rains” (Devi 119). According to Shankar, the outsiders could not maintain the respect of the land, as well as the culture of the natives of the land too. “Our land vanished like dust before storm, our fields, our homes, all disappeared. The ones who came were not human beings” (Devi 119). In addition to this, horror is expressed in the lines, “the forest disappears, they make the four corners unclean…” (Devi 119). The outsiders dug up the ancestral graves to construct roads to the extreme disgust and pain of the tribal people. “And so the unquiet soul casts its shadow and hovers . . . . This is surely the ancestors” spirit!” (Devi 120). Adequate propitiation to the ancestors not being done becomes the major concern for the tribals, who feel that this will doom the land and their tribes as well. Mahashweta reflects seriously on the concerns of the mountain-dwelling tribes, who are being gradually erased from the map of the world in a worthless bid to become modern. Her prose is a delight to read as it contains a wonderful tapestry of the characters, drawn dexterously from various walks of life. Puran Sahay is one such character, who is the ‘voice’ of the tribal condition prevailing. He has been invited by the Block Development Officer of Pirtha, Harisharan, who happens to be his bosom friend as well, to write a report on the drought and famine in the area. The story launches on to the mysterious truth from then on as there are references to an extinct animal right from the start itself. Pirtha has a distinct history of its own. The past experiences with the outsiders have been terrible and the coming of Puran is also viewed in the same manner by the tribals. Intrusion has just brought in devastation. The paintings reflect this amply. “I didn’t see the pictures five years ago . . . . And pictures of drunkenness, of communal dancing with drums, painted by the people . . . that’s awful hard, Puran ji. Can one measure the distance from the sun by releasing a kite?” says the SDO (Devi 106). The cave paintings mirror the devastation of the land honestly. Puran, too, is aware of the painting drawn by Bikhia, Shankar’s nephew but has no idea about the shadow of the Pterodactyl looming over Pirtha. In fact, the survey map of Pirtha reflects an extinct animal of Gondswana.

The agony of the people of Pirtha is multiplied by the government, who does nothing to solve their problems. It rather sends its officials to report on the famine and drought pervading the place in the monsoon. They are restricted from using the natural resources of water. All these and many atrocities make the tribals brutal and callous in their attitude towards the government and the outsiders. However, they like to watch the tribals singing and dancing on the Independence Day. This reduces them to objects merely, at the will and discretion of the outsiders ruling them.

Dishonesty is also portrayed in the implementation of the governmental policies. It decides to promote the land agrarian policy by providing fertilizers and pesticides, but it is not done honestly at all. Jaswant Rathod