3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

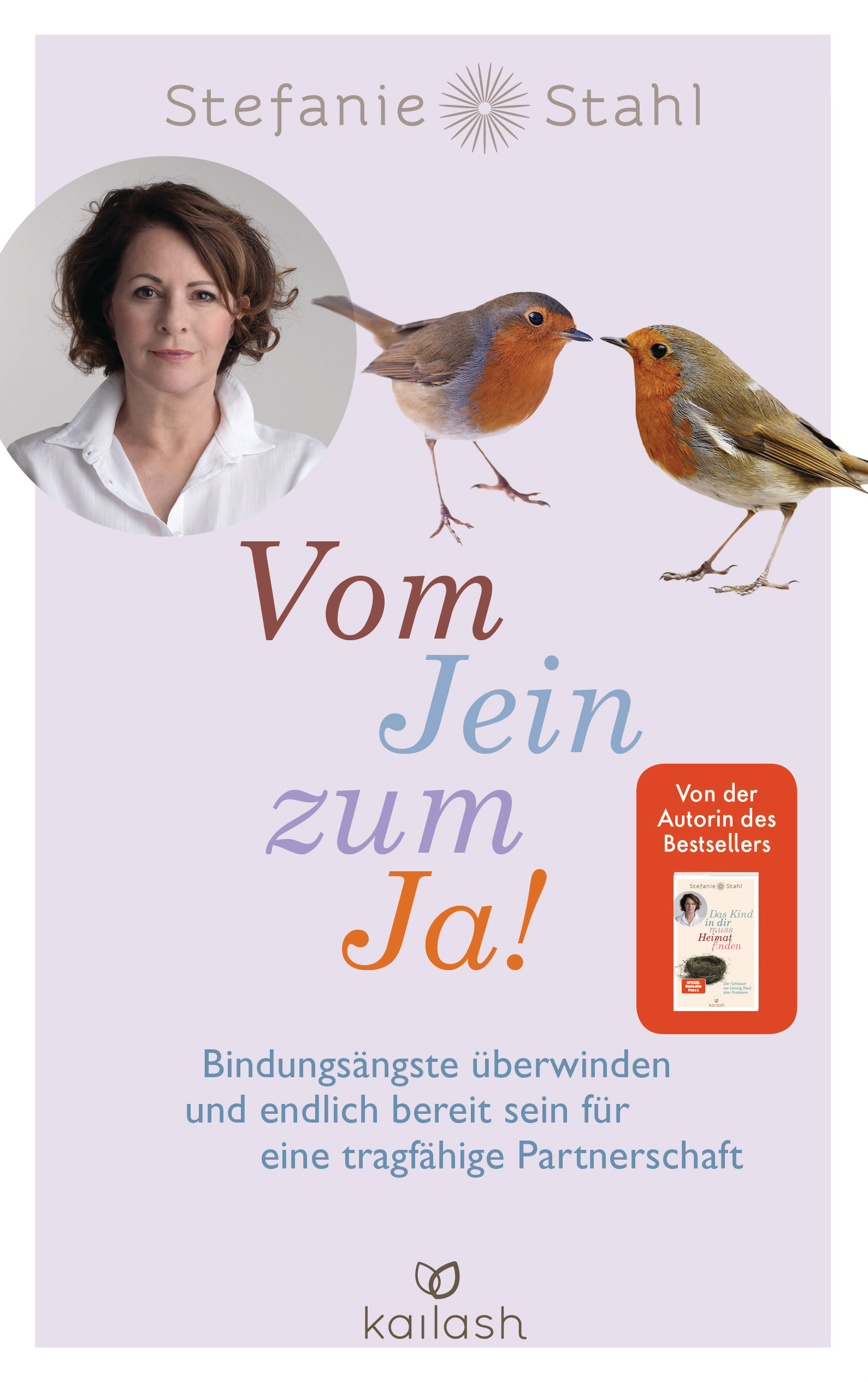

Nearly all human beings want a lasting, happy relationship, but in many cases it just doesn’t work out. Some people seem always to fall in love with the wrong kind of person. With others, the relationship breaks down just when it is becoming closer. And some live with a partner but still feel lonely and isolated. What is going wrong? ’In the final analysis, fear of commitment is at the bottom of many relationship problems,‘ says the expert on fear of commitment Stefanie Stahl. In vivid case histories, the German psychotherapist shows the many ways in which fear of commitment manifests itself. She explains the typical behavior patterns of those who fear commitment, introducing the ’hunters‘, ’princesses‘ and ’stonewallers‘. The famous German psychologist illustrates why fear of commitment is genuine fear, explains possible causes and shows how to overcome it. Anyone who has read this book will know how to recognize people who fear commitment and how to deal with them. A helpful book for those affected and for their partners.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 458

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

About the book

Nearly all human beings want a lasting, happy relationship, but in many cases it just doesn’t work out. Some people seem always to fall in love with the wrong kind of person. With others, the relationship breaks down just when it is becoming closer. And some live with a partner but still feel lonely and isolated. What is going wrong? ‚In the final analysis, fear of commitment is at the bottom of many relationship problems,‘ says the expert on fear of commitment Stefanie Stahl. In vivid case histories, the German psychotherapist shows the many ways in which fear of commitment manifests itself. She explains the typical behavior patterns of those who fear commitment, introducing the ‚hunters‘, ‚princesses‘ and ’stonewallers‘. The famous German psychologist illustrates why fear of commitment is genuine fear, explains possible causes and shows how to overcome it. Anyone who has read this book will know how to recognize people who fear commitment and how to deal with them. A helpful book for those affected and for their partners.

About the Author

Stefanie Stahl is a degreed psychologist with her own practice. She is one of Germany‘s best-known psychotherapists and holds seminars about fear of commitment, love and self-esteem on a regular basis. Her method for working with the inner child is a particularly imaginative and practical one, which has been resonating internationally as well. For years her bestselling books have been listed on the top ranks of the bestseller lists having sold more than one million copies. In 2019, her book The Child Within You Must Find a Home was for the third time in a row the bestseller of the year in Germany.

www.stefaniestahl.de

Stefanie Stahl

Yes, No,

Maybe

How to recognise and overcome fear of

commitment Help for those affected and

their partners

Translated by Mary Tyler and Paul Bewicke

The links in this book have been compiled with meticulous care and to the best of our

knowledge. However, we cannot assume any liability for the up-to-dateness,

completeness or accuracy of any of the pages.

Sollte diese Publikation Links auf Webseiten Dritter enthalten, so übernehmen

wir für deren Inhalte keine Haftung, da wir uns diese nicht zu eigen machen, sondern

lediglich auf deren Stand zum Zeitpunkt der Erstveröffentlichung verweisen.

Der Inhalt dieses E-Books ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und enthält technische

Sicherungsmaßnahmen gegen unbefugte Nutzung. Die Entfernung dieser Sicherung sowie die Nutzung durch unbefugte Verarbeitung, Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung

oder öffentliche Zugänglichmachung, insbesondere in elektronischer Form, ist untersagt und kann straf- und zivilrechtliche Sanktionen nach sich ziehen.

© 2020 Kailash Verlag, München

in der Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH

Neumarkter Str. 28, 81673 München

The English edition was first published at

Ellert & Richter Verlag GmbH, Hamburg 2015

The German original edition was first published at

Ellert & Richter Verlag GmbH, Hamburg 2008

Editor: Carola Kleinschmidt, Hamburg

E-Book-Conversion: CPI books GmbH, Leck

Satz und E-Book Produktion: Satzwerk Huber, Germering

Cover design: Daniela Hofner, ki 36 Editorial Design, München

Cover photo: Andrew Howe/getty images

Author’s photograph: Roswitha Kaster

ISBN: 978-3-641-27021-6V002

All rights reserved.

www.kailash-verlag.de

Contents

The many faces of commitment phobia

Why so many stories have an unhappy ending

I’m so much in love!

A plea for freedom of choice

Fear of commitment in various guises: the hunter, the princess, the stonewaller

Hunters, princesses and stonewallers – What those who fear commitment have in common

Help for sufferers – help for partners

Escape, attack, playing-dead reflex: the defence strategies

The three phases of a relationship with a person who fears commitment

Side effects of commitment phobia – Difficulties in everyday life

Causes of fear of commitment

The role of the mother

The role of the father

Secure or insecure – different styles of attachment

The secure attachment – “I’m OK, you’re OK”

The insecure attachment

The preoccupied attachment – “I’m not OK but you’re OK.”

The anxiously avoidant attachment – “I’m not OK and you’re not OK.”

EXCURSUS: An unfortunate combination: fear of commitment and narcissism

The dismissive-avoidant commitment – “I don’t care about me and I don’t care about you.”

A special case in dismissive avoiders: Quiet narcissists and lonesome cowboys

No attachment, no empathy

Does fear of commitment lead to a bad character?

The little difference: Fear of commitment in men and women

Fear of commitment and aggression: without attachment, people are unable to deal properly with aggression, anger and conflict

Upbringing, disappointment and society – Factors that encourage fear of relationships in later life

Does our society produce commitment phobes?

Ways out of commitment phobia for sufferers

Why it is worth taking this path

Eight steps out of fear of commitment – A guide to self-knowledge and change

EXCURSUS: Focusing – How to access your feelings

Linguistic tips for people who fear commitment

The partners of commitment phobes – Ways out of addiction

Powerless co-pilots – the partners of people who fear commitment

Emotional loss of control – When reason says “Finish it” but the heart says “Stay”

The madness can affect anyone

Emotional loss of control and its consequences for the partner

How to recognise emotional loss of control

Eight symptoms and action mechanisms of partners of people who fear commitment

Married to a commitment phobe – The resigned and the dreamers

Worn down by the relationship – The plunge into fear and depression

Negative reinforcement – When the relationship resembles an addiction

Ways out of loss of control – Finding your way back to yourself

Ways out of dependence: Nine aids to strengthening the adult in you

EXCURSUS: Why do I always end up with the wrong person? Desire for attachment and attachment compulsion

Farewell to my readers

A postscript for the psychotherapists among my readers

Acknowledgements

Annex

Before I fall in love

I’m preparing to leave her.

Robbie Williams

The many faces of commitment phobia

Why so many stories have an unhappy ending

Please don’t let this story have an unhappy ending, the protagonist in a Martin Suter love story pleads. In fact, it does end unhappily, albeit on a hopeful note. Although the relationship breaks down, it matures the protagonist. The novel ends with him starting to write a novel about his unhappy love affair.

In life, many love stories end unhappily without leaving their protagonists more mature. Instead, people embark on the next story with new characters and slight variations in the action. But the plot remains the same. What is more, it has another unhappy ending. This book aims to help its readers transform their own actions and to experience new stories that are more likely to have a happy end.

With the large number of self-help guides to relationship issues on offer, one might think that the world had enough of them. Most provide advice for couples who are bogged down in a relationship, couples who can no longer talk to each other without arguing, or couples who never argue but whose relationship has become rigid and tedious. They give helpful suggestions for changing and improving how couples talk to each other, for redeveloping respect for one’s partner and for rekindling passion. Some guides look into the natural differences between men and women and explain how they can cope with life together despite these differences.

All these books build on the same fundamental hypothesis – that two people have come together who are both able and willing to live as a couple. In other words, they address people who are fundamentally able to exist in a partnership. All further deliberations about the possible causes of partnership problems and their solution are based on this foundation.

That is precisely where this book is different. It starts one stage earlier, casting light on deep-seated and usually unconscious fears that doom close, trusting love relationships to failure from the outset. This does not mean that the people affected do not embark on relationships. Most do. But then, partly consciously and partly unconsciously, they ensure that the relationship falls to pieces. This book aims to reveal those destructive mechanisms that always come into play when a person actually yearns for closeness but is unable to live with the closeness of a relationship. It is no help to these people and their partners to give them golden rules for holding a constructive conversation or the best way to share housework and child rearing. Nor are their problems rooted in the biological differences between the sexes. Their relationships fail at a deeper level. It is “demons” in the psyche of these people which due to diverse fears ensure that no genuine closeness can be established and that the relationship breaks down.

Fear of commitment. A much-cited and apparently well-known phenomenon. Strangely, those affected do not usually feel that it refers to them. I have often observed that as a rule the person who fears commitment strongly resists the idea that they fear commitment. The partners affected struggle through a tangle of contradictions and inconsistencies in their loved ones’ behaviour and are also unable to identify the phenomenon by name. The same happens to those who (badly!) want a person who fears commitment as their partner but are somehow unable to capture him or her and secure their commitment. That is why we are familiar with the term commitment phobia but know few who are affected by it. In fact, there are many, though they rarely receive the correct “diagnosis.” In my view, this is because of the many different faces behind which fears of commitment can hide. So I would like to introduce you to the numerous faces of commitment phobia and explain the psychological causes. Only by recognising and understanding their fear can those who are affected change anything for themselves. In addition, partners or would-be partners of people who fear commitment can only change anything in their own behaviour if they understand the causes of the phenomenon and thereby gain an understanding of what makes these people so attractive to them. I will also describe specific steps for overcoming one’s fear of commitment or at least handling it better. In the final part of this book I would like to help partners, too, in a relationship with someone who fears commitment. Finally, this book is designed to give readers a compass, one that shows how to recognise commitment avoiders at an early stage, if possible before falling hopelessly in love with them and thereby almost inevitably heading for unhappiness.

This book is addressed to lay persons and experts. I deliberately put lay persons first because I am very keen to communicate psychological knowledge in such a way that everyone can benefit.

I’m so much in love!

No matter whether people who fear commitment or those capable of commitment enter into a relationship, it usually begins with an exhilarating feeling of being in love. So I would like to begin this book too with the phenomenon of being in love. Most people have experienced this feeling at least once, and mostly more than once. I advisedly say most, not all. It is old hat to say that romantic love marriage is an invention of the last century and that marriages of convenience used to be the predominant form. People in Muslim countries still say “Love comes after ten years.” That is in fact very clever, since love and partnership signify first and foremost mutual responsibility, being there for each other in good times and bad. A deep feeling of affection develops when two people go through life together, can rely on each other and feel the care and affection of the other. For this feeling it is not absolutely necessary to have been in love at the start of the relationship. This feeling results from a person’s actual experience with their partner over many years. In contrast, in the early stages of being in love we mainly project our own longings and dreams onto our partner. We see in him or her the person who will fulfil all our desires. However, this ecstatic state at the start of many relationships has little to do with love. What happens in our Western world is that one first falls in love and then attempts a relationship with that person as soon as love is returned. If you are lucky, being in love passes into love that is sustained over the years, sometimes until death. However, nobody can guarantee in advance that this love will really develop.

Here I make the possibly provocative claim that many love affairs would probably progress better if parents or good friends were to choose the partner. Good friends or parents (as long as they were reasonable people) would approach the matter with reason and appropriate distance so there would be a good chance of finding a partner who is really suited to you. Being in love is not necessarily the best guide when choosing a partner. Precisely in this state of being in love we tend to see the one we adore – and ourselves as well, incidentally – not only through rose-tinted spectacles but often also in a totally distorted light. That is because we are normally unaware of the inner experiences and patterns that ultimately play a role in determining who we do or do not fall in love with. So falling in love is a pure game of chance in which we blindly, or least in delusion, stake everything on one card.

Being in love per se is in any case a strange business. A friend of mine is of the not often encountered opinion that it is a terrible state, one that he never wants to go through again. He is married and, as far as I can judge, very happily, so he is not one of those characters who fear commitment that we will talk about in detail. (Though I should point out briefly that commitment phobes occasionally let themselves be carried away and marry!) This friend’s view of the state of being in love is as follows: “It’s a dreadful feeling, your stomach is always churning, you lose your appetite, all your thoughts are focused on that one woman, you virtually go stupid. You lose your cool and tremble. How can anyone wish for a state like that?” He is right. Because internally being in love feels like examination nerves and normally nobody wants those. Imagine you had all the symptoms of being in love and were about to take an examination – as it were you are in the corridor and the door is about to open and you are called into the exam. You will find that being in love and examination nerves feel amazingly similar. You have moist hands, butterflies in your tummy, can’t think of anything else, etc. Outside the door to the examination room you would rightly think, “I’ve got exam nerves” and not “I’m in love.” Why does the body feel two apparently so different situations so similarly? Because it is clever. Because being in love is like exam nerves. It is comparable to stage fright, which is also only a variant of exam nerves. When you are in love your thoughts seem only to revolve around the object of your desire. In fact, as so often, they revolve around yourself. Am I attractive enough? Does he/she rate me? Am I interesting? Am I his/her type? Or if you are already in the first stages of a relationship, new variations are added. Am I good enough for you to stay with me always? If you see me in the morning without my make-up, will you run away? When you notice what I am really like, will you lose interest? Or as Elisabeth Lukas, an author and psychologist I much admire, aptly puts it: “You tremble for your little bit of ego.” The same applies, incidentally, when someone leaves you. You ask yourself, “What did I do wrong? Wasn’t I goodlooking/intelligent/nice/understanding (the list can be continued ad lib) enough? In this case, you no longer tremble, but you weep for your “little bit of ego.” The internal drama comes to a head when you are left for someone else. What is so much better about him/her than me? I feel totally worthless and am deeply hurt that someone is supposed to be better than I am.

The questions “Will I get you?” and “Will you stay with me?” are closely intertwined with one’s own feeling of self-esteem. They are perceived like an examination, an examination of existential importance, and the examination subject matter is “Am I a lovable being? Will I get what I want in life? Can I influence what is important to me in life, that is getting this person as a partner and keeping him/her with me?” That is why many people’s world collapses when they are left, at least if the relationship was very important to them, if they were really “involved” in it. Yet I would assert that 90 per cent of the crying when you have heartache is for yourself. Love and relationships play a strong role in maintaining self-esteem and therefore have a self-preserving and thus subjectively a life-preserving function. Hence the emergence of sayings such as “You are like a part of me,” or “I can’t live without you” and “Losing the one you love is like dying.” In addition to their importance for our self-esteem, relationships have an existential significance. We humans are genetically designed to live in relationships, in kinships. So the loss of a relationship always has something very threatening about it at a deep, existential level.

While “normal” people take it for granted that if they venture into a relationship they may be left, or that a relationship always holds the risk of failure, a person who fears commitment does not allow things to progress that far. The commitment phobe always maintains a certain safety margin, he or she does not really become involved with a partner, or he or she avoids relationships entirely. His relationship mode is “Yes and No,” or “No,” but never “Yes.” One significant reason for this is the deep and usually unconscious feeling of a person who fears commitment that he or she would really not survive being left. In the depths of his or her being he or she is convinced that it would mean death. In contrast, those who risk genuine closeness have an inner conviction that although they would be terribly sad if things did not work out, at their innermost core they are sure that they would survive, and that sooner or later someone else would come along with whom things could work out. This inner self-confidence is a precondition for being able to trust someone else. This can be reduced to a simple formula: without self-confidence no confidence in others. Admittedly, people who fear commitment are normally unaware of the fear of failure that is the epicentre of their fear of commitment. Instead, they simply feel constrained by the thought of a permanent relationship or even marriage, as if they would fall into a trap.

At the conscious level there is usually a strong desire for freedom, which they see as badly endangered by a relationship. This desire arises primarily when they have fallen into a permanent relationship or if a casual relationship threatens to become too permanent. Provided they are not permanently tied, they can certainly feel a deep yearning for love and a relationship. That is why some run from relationship to relationship, always in search of the “right one.” Others are apparently living in a permanent relationship or are even married, but manage by means of numerous manoeuvres to maintain enough distance from their partners to keep their urge to escape in check. Others again are notorious bachelors or spinsters who do not get involved in permanent relationships and have more or less come to terms with living alone. Fear of commitment has many faces. It can hide behind a wide range of forms of relationship and be expressed in very different behaviours on the part of those affected. However, there is a common thread running through their underlying fears.

A plea for freedom of choice

Now one may ask the fully justified question “Does one necessarily have to live in a permanent relationship?” After all, there are so many interesting things, topics and people to devote oneself to without seeking one’s happiness in a permanent relationship, marriage or family. I wholly agree with this view. One can lead a very fulfilled life – or at least phases of one’s life – without living in a partnership. Living alone is in any case more fulfilling than persisting in an unhappy relationship or one that even makes you ill. However, something that I advocate wholeheartedly is that one should have inner freedom of choice. That applies both to people whose fear of commitment causes them great personal anguish and to those who feel little burden of suffering themselves but their partners all the more so. It also applies to all those more affected by the opposite of fear of commitment, that is those who cling to relationships even when they make them ill because they believe that they cannot live without a partner. Some people who fear commitment like to make a virtue out of a necessity by elevating their style of relationship, or their single lifestyle usually interrupted by affairs, into an art of living. Others muddle along in relationships without giving the matter much thought, while some worry a lot without understanding their problem or fail in their attempts to change something.

In any case, people who fear commitment cause a great deal of suffering to their partners or would-be partners. Consequently, fear of commitment is not solely their problem but inevitably that of their fellow players. Many take refuge in the convenient view that the other can leave at any time so he or she is responsible for going along with the situation or clinging to the relationship. Although this viewpoint is not entirely wrong, it goes too far in masking the protagonist’s own responsibility and transferring it to the other party. In fact, the person who fears commitment often plays a not inconsiderable role in making it difficult for the other person to leave him or her for once and all. Admittedly, the partner affected should also ask him- or herself some far-reaching questions about their inner motives for not giving the push to the one who shuns closeness.

I believe it is an essential part of everyone’s development, no matter whether they are afraid of commitment or not, to work at becoming aware of their inner motives, fears, convictions and needs. So every human being should make efforts to reflect. “Reflection” and “reflect” are psychologists’ favourite words and there is a reason for that. They mean making yourself aware of your inner thoughts, feelings and motives, or to put it the other way round, not pretending to yourself. Someone who acts after having reflected acts slowly and deliberately, so he has considered what he is doing – thought it through. However, someone who acts after having reflected has not only thought through what he is doing. It also means that he has good contact with his feelings and can therefore make a psychological link between his feelings, thoughts and deeds. However, it is not easy to understand oneself, because that requires tracking down even those emotions and hidden inner convictions that are not directly accessible to the consciousness. In computer language, one might say that one should recognise the operating system behind the user interface. In psychology we are fond of using the iceberg metaphor. Only the tip of the iceberg is visible above the sea. Beneath the surface hides a gigantic body. The tip of the iceberg is our consciousness, while the body represents the unconscious. Our actions, feelings and thoughts are largely controlled unconsciously and therein lies an enormous potential source of mistakes. Unlike an animal that as a result knows no unconscious conflicts and therefore acts correctly by instinct, human beings often instinctively do the wrong thing. This means that, in contrast to animals, we cannot necessarily rely on our instinct, our unconscious. For, because of our past, every one of us has a part conscious, part unconscious character that is not exclusively positive and healthy in anyone. The unconscious, suppressed parts of our being, which I like to describe as demons of the psyche, are very powerful. However, they do not reveal themselves. They often remain hidden in the background, from where they control what happens without their “host,” that is the person affected, being aware of it.

One could devote an entire book to the demons of the psyche and the power of the unconscious and there are countless books on the subject. So I will be brief. I mentioned above that commitment phobes are mostly unaware of their fears and tend to sense instead a vague urge for freedom that prompts them to numerous evasive manoeuvres. Some also cultivate specific ideologies to avoid looking their problem in the eye. This can be an individually manufactured private ideology such as the inner conviction “I am a very special being and until I meet someone who is the perfect match for me I won’t make any compromises.” Or simply, “I am above all this love business.” Others resort to existing world views, philosophies, religions or esoteric behaviours and use them to conceal their fear of commitment. For example, the ideal to which Buddhists aspire, that of releasing oneself from all ties, provides a customised philosophical hiding place for commitment phobes. This is how one can make a virtue of the necessity to be free from reflection and unburdened by deeper insights. As a matter of form alone, I record that this was surely not the intention of Buddha, of whom I entertain the positive assumption that he was a person who reflected and who treated his relationships with other human beings appreciatively and in a considered way.

Fear of commitment causes much suffering. Apart from those commitment phobes who genuinely and systematically stay away from relationships (and they are a minority), or those who find a fellow player who can accept the conditions without suffering (which happens very seldom), relationships with commitment phobes (that is, the majority) are marked by suffering and unhappiness. Entering into a relationship with a commitment phobe or running after him or her is an absolute guarantee for being unhappy.

Precisely because fear of commitment causes so much pain and suffering I am writing this plea for freedom of choice: one can be content with or without a love relationship. There are many good reasons for both forms of existence. There are also very many different relationship models to choose freely from, provided that all those involved agree. But every human being should accept responsibility for his or her actions – especially in relationships – and decide at some point, instead of settling for a perpetual “Yes and No” which means living at the expense of a partner or of constantly changing partners and affairs. It is also very important for partners to understand themselves and find the reasons why they accept so much suffering and are unable to free themselves from a relationship.

However, in order to change anything at all both the person affected and the partner must first recognise the problem of fear of commitment for what it is, and that is often not at all easy to do. So in the next section I will explore the many faces of fear of commitment and in subsequent chapters the problems of people who are unable to disentangle themselves from relationships involving a fear of commitment. Naturally, I will not just describe these problems and their causes but also offer solutions and help.

Fear of commitment in various guises: the hunter, the princess, the stonewaller

Let me now introduce you to several ways in which fear of commitment manifests itself. I will do so by sketching the typical course of some relationships where at least one partner has a fear of commitment. Some experts believe that the partners of people who fear commitment must fear it themselves because they would otherwise not have chosen that particular partner. I do not share this opinion, but more of that here. Fear of commitment comes in many guises, so the three following examples are just a small selection with which I hope to convey a sense of the underlying problems.

The hunter: I must have you – until I’ve got you!

Peter was not actually Sonia’s type at all. She met him at a party and they had enjoyed each other’s company but she was not particularly interested in him. Two days later he called to ask whether she would like to accompany him to a pub opening to which he had been invited. Sonia was attracted by the invitation, especially because the pub in question was a trendy one where she was likely to meet many other acquaintances, so she accepted on the spur of the moment. It was an enjoyable evening. Peter was clearly interested in her, but did not pressure her. He did not cling to her but circulated from time to time, talking to this person or that. He was good-humoured and uncomplicated. A few days afterwards he invited her to a meal in a smart restaurant. Sonia accepted, though she was already feeling slightly uncomfortable because she did not want to raise any false hopes. On the other hand, the invitation was enticing, so she accepted. Peter flirted with her again and she dropped some cautious hints that she could only reciprocate on “friendly” terms. That did not seem to bother Peter. He remained good-tempered and carried on flirting. After that, he often contacted Sonia to make a date, suggesting increasingly attractive activities. He was a chef in a gourmet restaurant, knew a lot of people and was often invited to wine tastings and other culinary events. He knew a lot about food and wine, so it was fun eating out with him. Meetings with Peter were always special, albeit not easy to arrange because of his working hours. Sonia particularly liked the fact that Peter was never offended if she had no time now and then and never seemed hurt when she rejected his advances. She found that very self-assured, and somehow cool. To cut a long story short, one evening Sonia stopped saying “No.” After they had drunk another glass of wine in her apartment, she spent the night with Peter. It was lovely. All next day, Sonia felt elated and warm. She had fallen a little bit in love. In the weeks that followed they met frequently, though not every day. Sonia was still struggling to decide whether she was doing the right thing. In some respects Peter did not match up to her expectations at all, and she doubted whether their relationship could work out in the long run. So she never mentioned the possibility of a future together. That did not seem to worry Peter, who made no attempt to nail her down. Then they had their first weekend away together, in a small, romantic town. They had a wonderful time and Sonia cast any remaining doubts aside. After that weekend she realised that she was really in love with Peter and could imagine a long-term relationship with him. Now she began to contact Peter. She often yearned for him and wanted to see him more often than before. However, Peter increasingly seldom had time. He would say he had a lot on in the restaurant, such as a wedding party or a company event. On his evening off he had to go to a wine tasting and he was sorry, but it was a men-only event. “I’ll call you tomorrow,” he would say. In short, Peter began playing hard to get and became unreliable, which he had never been before. Sonia suffered. She yearned for him. She was in love. What was going on? She discussed the problem at length with her women friends. “He said that, then he did this… then I said that, then I did that… Do you think he’s in love – or maybe not? How would you interpret the following situation …? ” And so on, and so on. The doubts gnawed at her and one evening when Peter did have time she challenged him to say what he wanted from her and how he saw the future of their relationship. Peter tried to talk his way out of the situation, saying: “At the moment the restaurant is taking up all my energy …; somehow I’m not ready …; I always have a wonderful time with you, I think about you often even if I don’t call …; give me a bit more time …; let’s keep it casual …” This conversation left Sonia feeling very confused. What exactly had he said? She racked her brains trying to make sense of it and to understand what was happening to him.

What happened?

Peter is one of those commitment avoiders that I call the classic “hunters” – and I must point out that this is not an exclusively male phenomenon. Their lives are interspersed with a large number of relationships and/or affairs. Some even have a marriage, or even several marriages, behind them. The hunter type is primarily interested in the hunt as such. In the early stages of a conquest or relationship he is usually unbeatable. Typically, he or she is charming, sociable and not at all easily offended. One thing Sonia liked especially about Peter was that he never seemed hurt at being rejected. Normally, rejection doesn’t matter much to hunters as long as they still see the chance of victory at a later date. On the contrary, a rebuff, provided it is not too final, sharpens their hunting instinct. Even a final rejection does not hurt them too badly, because they think, “There are plenty more fish in the sea. Give it another go.” Hunters can also be astonishingly patient in pursuing their goals. This gives their partners the erroneous impression that they must really be serious. The wooed individuals usually fail to realise that the hunter often has more than one piece of “game” in his sights, because hunters are usually good gamblers and adopt a clever approach. The course of Sonia’s and Peter’s relationship is typical. The hunter always loses interest when the hunt is over, normally at the moment when he or she senses that the prey is beginning to seem seriously interested in a relationship and feels “Now I’ve got you for sure.” This game can go on for years, especially if the person being hunted fears commitment him- or herself.

The princess: No-one is good enough for me

Rita and Thomas fell in love at first sight. They first met in a supermarket and were unable to take their eyes off each other. When Rita saw Thomas waiting at the checkout she went up to him, her heart beating wildly, and handed him her phone number. They had their first date the following evening and immediately became a twosome. Rita was madly in love. She felt her encounter with Thomas had been ordained by fate and was absolutely certain she had found Mr. Right at last. Thomas felt the same way and they spent several tempestuous months together. However, when Rita’s initial feeling of infatuation began to cool, more and more things about Thomas began to disturb her. Often she felt that his clothes did not match. He was also very long-winded and seemed to lack the intelligence to summarise essential facts. The extent to which he depended on praise from his boss irritated her, too. Increasingly, she found Thomas too up-tight and not sufficiently laid-back. Rita was not a person to mince her words and she spared Thomas no criticism. Only that, she thought, would give him the chance to change. Thomas rarely argued back, and agreed that she was right about many things. Somehow, even that irritated her. Secretly, she would have liked him to set some boundaries for her. That would have been manlier. Instead, he often had this sheepish, enamoured look that she found unbearable. Naturally, Rita also felt a bit guilty because after all Thomas had done her no wrong. She simply felt that he must work a bit harder on himself. Finally, Rita came to the conclusion that Thomas was not Mr. Right after all and that she needed a man who was more self-assured, someone with both feet more firmly on the ground. She finished with Thomas and felt liberated. His world fell apart. What had he done wrong?

In this case, it is Rita who has a commitment problem. You might argue that anyone could make a wrong choice and that does not necessarily mean that Rita was avoiding commitment. That is correct. As with all those who fear commitment (and others as well), it is crucial to look at the past. The same thing happened to Rita time and again. An intense phase of being in love and idealising her partner was followed by a second phase of denigrating him and removing him from his pedestal. This type of commitment avoider has highly narcissistic traits (see here). I would describe Rita as the “princess” or “prince.” She is capable of falling head over heels in love, usually at first sight. She is then intoxicated and is carried away by the feeling of being in love. She is not so good, however, at spending everyday life with a partner and tolerating his weaknesses. That does not give her much of a kick. It feels rather boring and stale, while she wants to live life to the full. Life has to be exciting. The last thing she wants is stagnation. For people like Rita, stagnation feels like “death” – as do permanent relationships. Rita is unaware of that and constantly yearns to find Mr. Right to offer her an exciting, eventful life. In addition, she wants a bit of “glamour” by her side. She must not only like her partner, she also wants him to be someone special who serves to boost her self-esteem. Very “ordinary” types have never attracted her. She keeps wondering why everyone else is lucky in love while she repeatedly ends up with the wrong man. Unlike Peter in our first example, who simply disappears from the scene, preferring to avoid conflict, Rita distances herself by denigrating her partner. She carps on and criticises him in an effort to shape him into her Mr. Perfect. However, because Thomas does little to defend himself, her respect for him diminishes. Disappointed, she turns her back on the putative prince of her dreams and sets out in search of the next fateful encounter.

The stonewaller – I will determine how close we get, or not

Irene and Lucas have been living together for six years. Lucas is a self-employed graphic artist and Irene works at a bank. Irene would like to have children but Lucas says he is not ready for that. He must first put his business on a firm footing. They still have time, he says. Even at weekends, Lucas often has to go to the office. For him, there is hardly any difference between work and leisure. Irene on the other hand always has weekends off and even on weekdays is usually home at about 6 pm, while it is not rare for Lucas to arrive home after 9 pm. Irene would like to spend more time with Lucas. What niggles her especially is that even when not working he spends a lot of time playing sports, and then goes for a drink with his friends. Another hobby of his is reading magazines. At weekends, if he is not at the office he spends hours reading the newspaper, political journals and computer magazines. Irene has a chronic feeling that spending time together is far more important to her than to him. She often feels alone, because even if Lucas is physically present he often seems mentally absent. So she often feels lonely even when he is in the room. Yet she is sure that he does not have another woman and that he does want a relationship with her. He always says so when she broaches the subject. He says he feels good about their relationship but he needs some space for himself. Irene also knows from experience that there is no point in trying to force him to spend an evening out with her occasionally if he does not feel like it. If she does so, he sits there completely “switched off.” Although he talks to her, all through the evening she has the feeling that he would prefer to be somewhere else. Then there are other evenings or days when he is “all there.” At moments like that she feels that he is very close to her and that he loves her, something she otherwise often doubts. Each time that happens she vows to stay relaxed and to trust in their relationship next time he distances himself. However, she usually fails to do so because Lucas is so “switched off” that she keeps falling into an “abyss of loneliness.”

Lukas is another typical example of someone who fears commitment. The notorious state of “yes, no, maybe” that shapes these people’s relationships is very evident in his behaviour. Clearly, he has allowed himself to become involved in a permanent attachment to Irene, but he has many ways of making sure he keeps his distance. Lucas “builds walls,” so one could call this type the “stonewaller.” He adopts some favourite strategies of people who fear commitment – work and passionate pursuit of hobbies. Another distinguishing feature is Lucas’s vague approach to time management. In general, commitment phobes do not like to be pinned down. That applies not only to relationships but as a rule to all areas of life. They always need to feel that they can decide freshly and freely, which is why they often end up in self-employment where few external structures can be imposed upon them. Often, self-employment also delivers the optimal pretext for being submerged in work. Another phenomenon that is very apparent in Irene’s and Lucas’s relationship is that the person who fears commitment is in charge. Lucas, and Lucas alone, determines closeness and distance in the relationship. He decides when he wants to be close to Irene and when not. He cannot come close for her sake. Even when she asks him to do so, he keeps his distance, only establishing closeness when he wants it. The loneliness that Irene often feels is simultaneously a feeling of helplessness because their life together is inadequate in every respect. She has no influence whatsoever on her desire to be close to him. While in healthy relationships give and take and compromises are part of the standard agenda, in commitment-phobic relationships power relations are settled unilaterally. The commitment phobe stakes out the boundaries and the partner has to put up with them.

Hunters, princesses and stonewallers – What those who fear commitment have in common

Ultimately, the drastic behaviour of the stonewaller Lucas is typical of all commitment-phobic individuals. The commitment phobe stakes out the boundaries of the relationship, whether like Lukas he decides he feels like talking or prefers to hide behind a newspaper or to burrow in his work, or whether like Peter the hunter he ultimately decides whether to meet often or not at all. The princess, too, settles the power relationships unilaterally by stipulating whether her partner is “right” or “wrong” and indulges in all manner of criticism, to the point of terminating the relationship because her partner does not live up to her idea of what he should be like.

In reality, the typical behaviours of the hunter, the princess and the stonewaller mingle in people who fear commitment. For example, if Rita the princess’s partner Thomas had remained independent, and had continued to do his “own thing,” thereby maintaining a distance between them, he would very probably have aroused Rita’s hunting instinct. Presumably she would have had nothing to moan about and would have focused entirely on catching and ensnaring Thomas, the “prince of her dreams,” along the lines of “He’s not particularly good-looking and we don’t have much in common, besides which he has a few stupid habits, but I’m crazy about him.” How often have you heard people say something like that? Or how often have you wondered, “Why is he/she wearing himself down on account of that man or that woman? “I love the one I can’t have” is the unconscious motto of many who fear commitment. In contrast, partners “secured” soon lose their appeal.

Another typical phenomenon in all types of commitment-phobic individuals is the conversation between Peter the hunter and his sought-after Sonia about their future relationship. In my view, all commitment-phobic individuals worldwide utter the words “I’m not ready yet” in every language. People who fear commitment don’t tie themselves down. They keep their options open and string their partners along. The sentence “I’m not ready yet” is great because it contains two statements, viz: I’m not ready YET, BUT (perhaps) I will be ready one day. The person to whom it is spoken can choose which he or she WANTS to hear. Does he or she want to hear the message, “I don’t want a permanent relationship” (which would be very intelligent) or does he or she – as people usually do – choose the message “It could still work out,” and start to fight? The inner conflict of commitment-phobic individuals, a conflict played out between the desire for closeness and relationship and a simultaneous fear of them, is thus very clearly mirrored in their language. It is that notorious “yes, no, maybe” that often drives (potential) partners mad.

The particular danger emanating from hunters is fundamentally that in their struggle for conquest they are hard to differentiate from people who are able to commit. Their very stubbornness can easily be misinterpreted as serious interest. Often, they really are serious. As I mentioned in my introductory chapter, most commitment-phobic individuals utterly deny fearing commitment. In other words, they often believe that their new heartthrob really is Mr. or Mrs. Right.

However, as soon as the hunter senses that a partner really wants him, he starts feeling uneasy because from that moment on he no longer senses only that he wants something but also that the other person wants something from him, too. Suddenly the hunter finds himself confronted by expectations, and expectations are deadly poison to every commitment phobe. For them, expectations signify something like confinement, loss of freedom, and being tied to someone’s apron strings. Above all, however, they signify – and most people are unaware of this – the possibility of disappointing the other person. I will go into this further in the third chapter of this book (see here in the section on “Fear of expectations”).

Help for sufferers – help for partners

Although none of the couples in the examples above were married or had children together, one must not forget that neither children nor marriage are criteria for ruling out fear of commitment. Fear of commitment is especially hard to recognise when sufferers come up against partners who fear commitment, for example, when a hunter comes up against a woman who repeatedly moves away from him. A client of mine who was married for 15 years summarised his marriage by saying that he had never got really close to his wife. He had spent 15 years fighting for her love. He also felt that his wife had only married him because she was pregnant with their first son and wanted to secure a “supply base.” After their separation (in the end his wife left him) he got to know his present girlfriend and now it was exactly the opposite. She wanted more from him than he was willing to give. A more in-depth analysis of his former relationships, marriage and current relationship revealed that in fact my client could only feel love and passion when it was not, or only very inadequately, reciprocated. As soon as he has “secured” someone he loses interest. The pattern is similar to that of Peter (the hunter) and Rita (the princess). However, because this client had started a family and had been married for 15 years, the underlying fear of commitment was very hard to recognise.

Likewise, it is perfectly conceivable that Irene and Lucas the stonewaller will stay together for years to come, that one day Ira will become pregnant and that Lukas will then marry her, albeit reluctantly. Purely externally, this will create the impression of a functioning relationship, albeit one that, internally, features decidedly commitment-phobic structures. Possibly, too, Irene also suffers from fear of commitment and is only so interested in Lucas because he never becomes really involved with her. In that case she would be in a similar position to the client who had been married for 15 years.

Help for sufferers: The first and most important step for sufferers is self-awareness. That means, first, awareness that one is very afraid of entering into a relationship and therefore adopts any means to prevent it. Second, it means awareness that this fear of relationship and closeness to another person is actually a great fear of dependence that usually has its roots in early childhood. Having become aware of these connections one can begin to recognise one’s behaviour at that level of awareness, thereby laying the foundation for change. The concrete steps in which this self-awareness and transformation from commitment phobe to someone capable of commitment are described here, Ways out of Fear of Commitment for Sufferers. In eight steps you can fathom the causes of your fear of commitment, access your submerged feelings and obtain practical suggestions for a new way of dealing with closeness, relationships and partnership.Help for partners: Though it sounds paradoxical, partners of people with commitment phobia in particular must learn to become considerably more independent of their partners. Frequently, partners of people who fear commitment are making a mistake that is only evident from a distance. Because the relationship is so dramatic, always up and down and never coming to rest, partners often reach the erroneous conclusion that this particular relationship and that particular person are very out of the ordinary and that their relationship is unique. Only by taking a step back internally and focusing on oneself and one’s feelings instead of on the relationship drama will one comprehend the mechanisms and illusions of a relationship with a commitment phobe and, with this newly acquired clarity, be able to act again.Here you will find nine helpful suggestions as to how you as a partner in a relationship where there is a commitment disorder can find your way to your true self, to greater clarity in your relationship, and to practical consequences.Escape, attack, playing-dead reflex: the defence strategies

Please be aware that fear of commitment is a genuine fear and that a sufferer’s reaction to the “threat” of an attachment is therefore the typical reaction of anyone who is afraid and finds himself or herself exposed to a threat. Commitment-phobic individuals react by attacking, escaping or playing dead. Fundamentally, our brain knows only these three ways of reacting to a major threat. Depending on how it manifests itself, the reaction to fear may be expressed by palpitations, gastro-intestinal disorders, feelings of suffocation, breaking out in sweats, etc. In a lot of cases, however, the person who fears commitment does not sense the fear clearly but instead feels a vague discomfort, an urge to be free, a “something” that makes him or her experience the relationship as unpleasant.

In many cases (not all), fears of commitment emerge at a very early stage of a child’s development, for example in the period between birth and the second year of life, that is a period when the infant’s survival depends on the care and affection of its attachment figures. If during that period no healthy bond is established with key attachment figures such as mother and father, if for example the child lacks care or affection, instead of trust it develops a fear of attachment. At a very deep and usually unconscious level, fear of commitment is therefore an existential fear that has its origin in very early childhood. For sufferers, it is subjectively a matter of life and death. In the second part of this book I will go into the causes of fear of commitment in detail. I will begin by describing the strategies that people who fear commitment use to overcome that fear. Most sufferers have at least two strategies at their disposal. If you recognise some of the strategies in your partner or in your relationship, you can assume that you are dealing with a sufferer from commitment phobia. If you yourself are acquainted with one strategy or another you are probably one of those people who find it difficult to enter into a firm commitment. It is particularly worthwhile for you to continue reading this book.

Escape as a defence strategy

The most frequent strategy and one adopted by all commitment phobes is escape, by an infinite number of routes. The most extreme escape route is to refrain from embarking on a relationship with a potential partner entirely, but merely to have an affair, to flirt or, even more extremely, to worship them from afar. The other extreme escape route involves terminating the relationship abruptly and in a way that the partner cannot foresee. Between these extremes are numerous lesser and greater escape routes.

I. Escape before the relationship begins

“Whenever I see Joe he flirts with me and really comes on strong. But he never asks me for a date. Recently, when I asked if he wanted to accompany me to a certain film, one we had talked about, he ducked the issue, saying he couldn’t plan properly at the moment because he had such a lot on.” (Sabrina, 27)

“I don’t know what to do any more. For two years, I’ve been madly in love with my boss. He’s married, I don’t know whether happily or not because he never talks about his private life. Sometimes I think he feels something for me when he looks at me in a certain way. But I’m not sure. I hardly think about anything else and rack my brains wondering whether he has any feelings for me. I know it is completely stupid and that it would be better to get him out of my mind. But whenever I see him I get palpitations. I have no inclination toward the other men I meet who might be interested in me.” (Mike, 35)

“Whenever I see Sarah, it starts all over again. We just can’t get away from each other. Sooner or later I end up in bed with her even though I know in advance that afterwards she will disappear from the scene for weeks and I will be suffering again. But somehow I still believe in a happy ending. One day she won’t run away any more.” (Rolf, 41)

These three examples are of couples where at least one of the two has a commitment problem and “escapes before it begins” by making sure that, despite all the passion, love and longing, no relationship comes into being. In the first example, Joe engages in typical rapprochement-avoidance behaviour. He engages in vaguely promising flirtatious behaviour, but as soon as Sabrina takes a step towards him he leaves her in a vacuum, along the lines of “lure then block.” Even if Joe and Sabrina are only flirting, the dichotomy of the commitment-phobic individual is evident. “Come close to me and stay away from me” is the dual message in every version.