Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

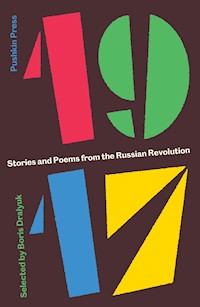

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

?'This is the last of you, old world - soon we'll smash you to bits.'The passionate voices of radicals, dreamers, workers, aristocrats, satirists and romantics fill these electrifying poems and prose pieces, written between 1917 and 1919 in the full tumult of the Russian Revolution.From apocalyptic visions to heartfelt calls for freedom, from depictions of bloody carnage to an acerbic portrait of Lenin, the writings brought together here are by turns fervent, absurd, disorienting and tragic.Some writers - Bulgakov, Pasternak, Mayakovsky, Akhmatova - are well-known, others all but forgotten; many would not survive what was to come. All speak to us a century later, re-creating the whirlwind of euphoria and terror, hopes and betrayals of that exhilarating, brutal time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 270

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1917

Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution

Selected by Boris Dralyuk

PUSHKIN PRESS

Contents

Editor’s Note

The pieces I’ve chosen for this collection were written between February 1917, when the revolutionary forces in Petrograd and Moscow toppled the Romanov dynasty, and late 1919, when the Bolsheviks, who had seized power on 25 October (7 November, NS) 1917, finally turned the tide against the White Army in the Russian Civil War of 1917–21. The rationale for limiting the anthology’s scope to these two and a half years was simple: My aim was not so much to tell the story of the revolutionary period as to steep the reader in its tumult—to recreate the heady brew of enthusiasm and disgust, passion and trepidation that intoxicated Russia and the world as the events unfolded. Consequently, I wanted to avoid memoirs and retrospective works of fiction, as well as commemorative poems, of which there is no dearth. These backward-looking works, be they written from a Soviet or anti-Soviet perspective, treat the revolutions and the Civil War as a single fait accompli, a decisive but entirely decided matter. Many important longer works are also readily available in stand-alone translations; I draw on and point to these works in the introductory notes to the anthology’s subsections.

As for the story of the Russian Revolution, it has been told many times. In English, it has been covered especially well by Orlando Figes, Sheila Fitzpatrick and Robert Service, and this anthology may be read alongside their volumes. Since my target audience is English-speaking, I have tried to use English-language sources in my notes whenever possible.

The first part of the collection, ‘The Revolution: A Poem-Chronicle’, takes its title from a long poem by Vladimir Mayakovsky (see pp. 68–70), written in the month or so following the February Revolution, in which the poet declares:

The courses of planets,

the existence of states:

all are subordinate to our wills.

The earth is ours.

The air is ours.

Ours is the diamond mine of the stars.

And we will never—

no, we will never!—

permit a soul—

no, not a soul!—

to tear at our earth with cannon balls,

to pierce our air with the points of spears.

(Translated by James Womack)

Mayakovsky’s radical prediction that the events of February would bring about lasting peace was, of course, proved tragically wrong. The Provisional Government refused to withdraw Russian troops from the First World War, a fact the Bolsheviks used to justify their takeover in October. And though the Bolsheviks did secure a peace with the Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918, their coup plunged Russia into a protracted civil war, with Russia’s former allies—including the French, the British and the Americans—intervening on behalf of the White opposition. The combination of passionate idealism and tragic misapprehension in Mayakovsky’s poem lends it great poignancy. His “poem-chronicle” could not have been written in the 1920s, after the dust of 1917 had settled. I feel the same can be said of most of the poems I have selected for my “poem-chronicle”. They are grouped in six sections, each linked by a common theme, attitude or striking image. The introductions are brief, and anyone wishing to learn about the lives of most of these poets and to read more of their work may consult The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry (2015), edited by Robert Chandler, Irina Mashinski and myself.

The second part of the collection is devoted to prose, and it too is separated into sections linked by theme or some other unexpected commonality. The introductions to these sections are more substantial, providing fuller biographical sketches of the authors, many of whom are little known in the English-speaking world, and some of whom are almost forgotten even in Russia. I have also included one story translated from the Yiddish of Dovid Bergelson, as well as a poem translated from the Georgian of Titsian Tabidze; the events of 1917 affected all the peoples of the Russian Empire, and had I the space, I would have included pieces translated from Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish, Ukrainian and the languages of Central Asia. Had I more space yet, I would have included works by authors from around the globe, since the days of 1917 did indeed, to paraphrase John Reed, shake the world.

Much of my work on this anthology was done in Scotland, and I would like to illustrate the riches I have had to exclude for reasons of language, geography and chronology by quoting Hugh MacDiarmid’s (1892–1978) electrifying quatrain ‘The Skeleton of the Future (At Lenin’s Tomb)’, written in the early 1930s:

Red granite and black diorite, with the blue

Of the labradorite crystals gleaming like precious stones

In the light reflected from the snow; and behind them

The eternal lightning of Lenin’s bones.

Acknowledgements

I must thank Adam Freudenheim, Gesche Ipsen and Julia Nicholson at Pushkin Press, for commissioning me to work on this dream of a project and for all the support and encouragement they have given me along the way. I owe a great debt to the brilliant translators who have contributed their talents to this anthology: Josh Billings, Maria Bloshteyn, Michael Casper, Robert Chandler, Peter France, Rose France, Lisa Hayden, Bryan Karetnyk, Martha Kelly, Donald Rayfield, Margo Shohl Rosen and James Womack. It is my honour to foreground their work, and I am just as honoured to reintroduce the work of translators who are no longer with us: Mirra Ginsburg, Jack Lindsay, Alex Miller, Gerard Shelley and Jon Stallworthy. I am deeply grateful for the help and advice of my colleagues Emily Finer, Victoria Donovan, Katharine Holt, Olga Voronina and Claire Whitehead of the University of St Andrews, and Yelena Furman, Georgiana Galateanu, Olga Kagan, Susan Kresin, Gail Lenhoff, Lada Panova and Ronald Vroon of UCLA. I am especially grateful to Sean Griffin, Roman Koropeckyj and Michael Lavery of UCLA, who—quite characteristically—went above and beyond the call of collegial duty. An event dedicated to this anthology at Pushkin House in London in October 2015, organized by Ursula Woolley, brought together an extraordinarily informed audience, including the poets D.M. Black, Stephan Capus, Peter Daniels and Stephen Watts, who made invaluable comments on the works I presented. Edythe Haber, an expert on Teffi, helped me sort out some mysteries regarding that author’s work. I have saved my final tip of the hat for the remarkably knowledgeable and perceptive Stephen Dodson, whose sharp eyes have rescued me from myriad blunders. Needless to say, the blame for all remaining blunders lies with me.

I would like to dedicate this anthology to the memory of my grandmother, Yekaterina Pavlovskaya, who was a two-year-old girl in Odessa when the Bolsheviks seized power in Petrograd in 1917, and who outlived the Soviet Union by twenty-one years.

THE REVOLUTION

A Poem-Chronicle

STOLEN WINE

In 1917 Maxim Gorky (1868–1936), a friend of Vladimir Lenin’s since 1907, began to publish a series of articles in the Petrograd daily Novaya Zhizn (New Life), raising serious questions about the behaviour of the Russian masses during that revolutionary year and, most daringly, about Bolshevik policy after the seizure of power in October. These “untimely thoughts” established Gorky, a committed Marxist, as “the conscience of the revolution”. On 7 December 1917, Gorky complained:

Every night for almost two weeks crowds of people have been robbing wine cellars, getting drunk, banging each other over the head with bottles, cutting their hands with fragments of glass, and wallowing like pigs in filth and blood. Over this period, wine worth several tens of millions of rubles has been destroyed, and, of course, hundreds of millions of rubles’ worth will continue to be destroyed.

Russians had lived under a limited dry law since the beginning of the First World War. Did they really desire political freedom or merely a drunken free-for-all? Gorky wasn’t the only one to sense the deeper implications of this looting. Depictions of the “wine riots” run like a red stream through the work of monarchist and liberal diarists, memoirists and authors recoiling from the chaos of 1917. The organs of Bolshevik propaganda laid the blame for the riots squarely at the feet of the bourgeoisie, and the new government’s international supporters helped spread that message far and wide. In his slanted but marvellously evocative Through the Russian Revolution (1921), Albert Rhys Williams toed the party line:

In their efforts to befuddle the brains of the masses the bourgeoisie saw an ally in alcohol. The city was mined with wine cellars more dangerous than powder magazines. This alcohol in the veins of the populace meant chaos in the life of the city. With this aim the cellars were opened and the mob invited in to help themselves. Bottles in hand the drunks would emerge from the cellars to fall sprawling on the snow, or rove thru the streets, shooting and looting.

To these pogroms the Bolsheviks replied with machine-guns, pouring lead into the bottles—there was no time to break them all by hand. They destroyed three million rubles’ worth of vintage in the vaults of the Winter Palace, some of it there for a century. The liquor passed out of the cellars, not thru the throats of the Czar and his retainers, but thru a hose attached to a fire-engine pumping into the canals. A frightful loss. The Bolsheviks deeply regretted it, for they needed funds. But they needed order more.

Gorky, for his part, saw through all this: “Pravda writes about the drunken riots as a ‘provocation of the bourgeoisie’ which, of course, is a lie, an ‘eloquent phrase’ that can increase bloodshed.” Propaganda notwithstanding, the sight of drunken burghers, peasants and soldiers—of wine mingling with blood—left an enormous impression on all those who lived through those days.

The young Marina Tsvetaeva, who would eventually emerge as one of the major poets of the twentieth century, taps into this current in a riveting poem set in the Crimean port of Feodosia—the half-sprung, half-reeling rhythm of her verse providing a perfect formal analogue to its apocalyptic themes and imagery. Beneath the poem, she added: “NB! The birds were drunk.” It is drawn from a collection that Tsvetaeva completed but didn’t publish during her lifetime, The Demesne of Swans, in which, as Peter France writes, “she praised the nobility of those who died for the anti-revolutionary cause. They are swans, white and pure, against the ravens.” But with Tsvetaeva things were never quite so simple. France continues: “There is no doubt about Tsvetaeva’s position at this time, but equally there is no doubt that her heart went out above all to the gallant loser, the victim.”

In his study of the poet, Simon Karlinsky explains her shifting allegiances throughout the year—she dedicated poems to Tsar Nicholas II after his abdication, but also wrote a poem to Alexander Kerensky, the leader of the Provisional Government, in which she compares him, favourably, to Napoleon, and a sequence valorizing the seventeenth-century rebel Stenka Razin: “Her basic humanity invariably led Tsvetaeva to take the side of the underdog, which for her meant any individual of whatever station who was threatened by a dehumanized collective, be it a mob, a political party or the state.” Owing partly to this idiosyncratic stance and to the formally “revolutionary” nature of her poetics, Tsvetaeva never felt at home among the émigrés in Paris, where she finally settled in 1925, after leaving Soviet Russia in 1922 and spending some time in Berlin and Prague. Writing to a Czech friend in 1929, she complained that, “For those on the Right—[my work] is ‘left’ in form. For those on the Left—it is ‘right’ in content.” A decade later, Tsvetaeva returned to the Soviet Union, following her husband Sergey Efron, a former White officer who had begun working for the NKVD (the Soviet secret police), and daughter Ariadna, who shared her father’s pro-Soviet views. Not long after Tsvetaeva’s arrival, Efron and Ariadna were arrested for espionage; Efron was executed in 1941 and Ariadna was sentenced to eight years in prison. Emotionally devastated and lacking any means of support, Tsvetaeva hanged herself on 31 August 1941.

The older Symbolist Zinaida Gippius, who saw the carnage and Bacchanalia around her as a betrayal of the democratic ideals of several generations of Russian freedom fighters, dating back to the Decembrist Uprising of 1825, also seizes on the image of “stolen wine”. Both Tsvetaeva and Gippius ponder the nature of the people’s new-found freedom: Gippius despairs at what the Russians had done with this Beautiful Lady they had anticipated, while Tsvetaeva, who was wary of the year’s revolutionary developments from the start, doubts the Lady was ever who she appeared to be. These poems offer a vivid portrait of the tumult unleashed by the February and October Revolutions, and, in the case of Gippius, the disenchantment they triggered even among those who were eager to see Russia transformed.

MARINA TSVETAEVA (1892–1941)

You stepped from a stately cathedral

onto the blare of the plazas…

—Freedom!—The Beautiful Lady

of Russian grand dukes and marquises.

A fateful choir’s rehearsing—

the liturgy still lies before us!

—Freedom!—A street-walking floozy

on the foolhardy breast of a soldier!

26 MAY 1917

(Translated by Boris Dralyuk)

Night.—Northeaster.—Roar of soldiers.—Roar of waves.

Wine cellars raided.—Down every street,

every gutter—a flood, a precious flood,

and in it, dancing, a moon the colour of blood.

Tall poplars stand dazed.

Birds sing all night—crazed.

A tsar’s statue—razed,

black night in its place.

Barracks and harbour drink, drink.

The world and its wine—ours!

The town stamps about like a bull,

swills from the turbid puddles.

The moon in a cloud of wine.—Who’s that? Stop!

Be my comrade, sweetheart: drink up!

Merry stories go round:

Deep in wine—a couple has drowned.

FEODOSIA, THE LAST DAYS OF OCTOBER 1917

(Translated by Boris Dralyuk)

ZINAIDA GIPPIUS (1869–1945)

Now

The streets are slippery and vile—

disgrace!

Life is so shameful, so incredible

these days!

We all lie bound, bespattered,

on every street.

Our foreheads are all smeared

with sailors’ spit.

Our guardians and warriors

have all retreated.

There’s no one but conformists,

with their Committees.

We’re all a bunch of homeless curs—

completely stranded!

The Bolsheviks tore up the rails

with sooty hands…

9 NOVEMBER, 1917

(Translated by Boris Dralyuk)

What Have We Done to It?

Our grandads’ outlandish dream,

the prison years of our heroes,

our lament and our hope,

the prayer we hardly dared utter—

our scuttled, shattered,

Constituent Assembly?

12 NOVEMBER 1917

(Translated by Robert Chandler)

14 December 1917

For Dmitry Merezhkovsky

Will our pure heroes grant us pardon?

We didn’t keep their covenant—

all that is holy has been squandered:

our shame, the honour of our land.

We stood beside them, stood together,

when storm clouds gathered in our skies.

The Bride appeared. And then the soldiers

drove bayonets through both her eyes.

We drowned her amid petty quarrels,

in stolen wine, in Palace vats.

The royal axe and noose were cleaner

than these apes’ bloodied hands!

Golitsyn, Trubetskoy, Ryleyev!

You’ve gone now to that far-off land…

Your faces would all blaze with wrath,

seeing the Neva’s sullied banks!

From this low pit, this bitter torment,

where acrid smoke circles the depths,

we stretch our trembling arms towards

your distant sacred robes.

To lay hands on those burial garments,

to touch them with our lifeless lips,

to die, or maybe to awaken…

Can’t live like this! Can’t live like this!

(Translated by Boris Dralyuk)

OSIP MANDELSTAM (1891–1938)

In public and behind closed doors we slowly

lose our minds,

and then the brutal winter offers us

clean, cold Rhine wine.

The chill extends to us, in silver buckets,

Valhalla’s wine,

which calls to mind the fair-haired image

of Northern man.

But Northern skalds are crude,

don’t know the joy of games,

and Northern warriors are fond

of amber, feasts and flames.

They’ll never taste the Southern air—

enchanted foreign skies—

and so the stubborn maiden

will refuse their wine.

DECEMBER 1917

(Translated by Boris Dralyuk)

A DISTANT VOICE

With its palpable longing for the gentle air of the Mediterranean—associated with the sustaining, civilizing forces of Western culture—Mandelstam’s ‘In public and behind closed doors…’ is a typically Acmeistic reaction to the upheaval of 1917. The Acmeist group, founded in 1912 by the gallant, adventurous warrior-poet Nikolay Gumilyov (1886–1921) and Sergey Gorodetsky (1884–1967), rejected the mystical vagaries of the preceding generation of Russian poets, emphasizing instead the virtues of clarity, harmony and mastery of technique. Their poetry was, in effect, a turn towards the phenomenal world—the world as it is, not as a sign or symbol of some noumenal realm lying beyond it. As Gorodetsky wrote in one of the movement’s earliest manifestos, “For the Acmeists the rose has once again become beautiful in itself, through its petals, scent and colour, and not through its imagined similarities to mystical love or whatever else.”

Gumilyov organized a “Guild of Poets”, a workshop to develop and spread his poetic principles, and this exclusive milieu fostered two of the most important poetic talents of the twentieth century, Mandelstam and Gumilyov’s wife until 1918, Anna Akhmatova. The Acmeists’ turn towards the world meant a responsiveness not only to nature, to urban life and to culture, but also to politics. All wrote poems about the First World War, though each from a different perspective: Gumilyov as an officer in the Imperial Army, Akhmatova as a wife on the home front, and Mandelstam as an intellectual grappling with the forces of history. One might have expected the same level of engagement in the aftermath of 1917. Gumilyov, who was stationed abroad in 1917, returned to Soviet Russia in 1918. Although he didn’t write overtly political poems, he never hid his monarchist views or his allegiance to the Orthodox faith. His avoidance of politics in his poetry didn’t save him; he was arrested on 3 August 1921, accused of participating in an anti-government plot, and executed on the 25th of that month along with sixty alleged co-conspirators.

Mandelstam, who was closest politically to the Socialist Revolutionaries, spent the years 1917–22 shuttling between Red, White and neutral territory, turning up in Petrograd, Moscow, Crimea, Kiev and Tiflis. His poems reflect not only his own conflicted feelings about Russia’s radical transformation but also the confusion in the air. He and Akhmatova, who stayed in Petrograd and wrote mostly personal verse in those years, have one attitude in common: both cast their lots with Russia and its people, regardless of how they feel about the Bolsheviks and their stewardship.

Akhmatova’s and Mandelstam’s fates during the Soviet era are well known, even legendary. Mandelstam’s life ended in tragedy, a death in a transit camp near Vladivostok on 27 December 1938. Akhmatova survived years of persecution under Stalin, which included the long imprisonment of her son Lev Gumilyov. Despite the authorities’ best efforts, her death on 5 March 1966 triggered an enormous public outpouring of grief. Her funeral and the memorial services that followed allowed her admirers to mourn her passing, but also to celebrate her personal triumph and her generation’s achievement.

Boris Pasternak is known in the West primarily as the author of Doctor Zhivago (1957), but he was, first and foremost, a poet. Despite being nominally associated with the Futurist group “Centrifuge” throughout the 1910s, he was personally close to Tsvetaeva, Akhmatova and Mandelstam, while his poetics were all his own. The year 1917 was an enormously stimulating and productive time for the poet, and it was the political turmoil of those days and months that—however indirectly—inspired his first masterpiece, the collection My Sister, Life, as well as its companion volume, Themes and Variations. ‘Spring Rain’ is one of only two poems in My Sister, Life that makes direct mention of political events, but the whole collection resonates with revolutionary energy. In an autobiographical sketch titled ‘People and Propositions’, written in 1956–57 but not published until 1967, Pasternak described his and his nation’s state between February and October 1917:

A multitude of excited, keenly watchful souls would stop one another, flock together, form crowds and think aloud “in council”, as they would have said in the old days […]. The infectious universality of their elation blurred the boundaries between man and nature. In that famous summer of 1917, in the interval between two revolutionary periods, it seemed that the roads, the trees and the stars were rallying and speechifying right along with the people. The air was seized from end to end with fervid inspiration that blazed for thousands of versts—it appeared to be a person with a name, to be clairvoyant and possessed of a soul.

OSIP MANDELSTAM (1891–1938)

Let’s praise, O brothers, liberty’s dim light,

the great and sombre year!

A forest of thick snares is plunged

into the boiling waters of the night.

You are ascending into god-forsaken years,

O people—sun and judge.

Let’s praise the fateful burden

the people’s leader shoulders through his tears.

Let us praise power’s sombre burden,

a weight one can’t withstand.

Whoever has a heart, O time, must hear

your ship sink and descend.

We have bound swallows

into warring legions—now

we cannot see the sun; the elements

all chirp, stir, terribly alive;

through the thick twilight of the nets

we cannot see the sun, while the Earth sails.

Well then, let’s try it: an enormous, ponderous,

creaking rudder-turn.

The Earth sails. Courage, men.

Cleaving the sea as with a plough

we shall recall, even in Lethe’s bitter cold,

that the Earth’s price was all ten spheres of paradise.

MAY 1918, MOSCOW

(Translated by Boris Dralyuk)

ANNA AKHMATOVA (1889–1966)

When the nation, suicidal,

awaited German guests,

and Orthodoxy’s stringent spirit

departed from the Russian Church,

when Peter’s city, once so grand,

knew not who took her,

but passed—a drunken harlot—

hand to hand,

I heard a voice. It called me.

“Come here,” it spoke consolingly,

“and leave your senseless, sinful land,

abandon Russia for all time.

I’ll scrub your hands free of the blood,

I’ll take away your bitter shame,

I’ll soothe the pain of loss

and insults with a brand new name.”

But cool and calm, I stopped my ears,

refused to hear it,

not letting that unworthy speech

defile my grieving spirit.

AUTUMN 1917

(Translated by Margo Shohl Rosen and Boris Dralyuk)

BORIS PASTERNAK (1890–1960)

Spring Rain

It grinned to the bird-cherry, sobbed and soaked

the gloss of carriages, the flutter of pines.

Under the bulging moon, fiddlers in single file

make their way to the theatre. Citizens, form lines!

Puddles on stone. Like a throat full of tears,

deep in the heart of a rose’s furnace

damp diamonds burn, and on them, on clouds,

on eyelids, the wet lash of happiness.

The moon for the first time models in plaster

epic queues, tossing dresses, the power

of enraptured lips; it models a bust

modelled by no one until this hour.

Whose is the heart in which all this blood

rushed from the cheeks, rushed in a flood

to glory? The minister’s fingertips

have squeezed together aortas and lips.

Not the night, not the rain, not the chorus

shouting, “Hurrah, Kerensky!” but now

the blinding emergence into the forum

from catacombs thought to have no way out.

Not roses, not mouths, not the roar

of crowds, but here, in the forum, is felt

the surf of Europe’s wavering night,

proud of itself on our asphalt.

1917

(Translated by Jon Stallworthy and Peter France)

WAKE ME TOMORROW

Emotionally fatigued by the nation’s senseless losses in the First World War and utterly disenchanted with the moribund tsarist regime, many writers and artists from a variety of backgrounds were ready to accept the revolutionaries’ promises of freedom and justice for all. Revolutionary enthusiasm seized even the most rarefied aesthetes, like the openly homosexual poet Mikhail Kuzmin, whose devotion to “beautiful clarity” (the title of one of his essays from 1910) had so inspired the Acmeists. Kuzmin’s diary for 1915–17 is lost, but his biographers, John E. Malmstad and Nikolay Bogomolov, have managed to reconstruct their subject’s reaction to the February Revolution:

The testimony of several other sources indicates that Kuzmin was as weary of the senseless killing at the front as were most Russians, and that he welcomed a revolution that he hoped would bring an end to the war. (His constant anxiety about the draft status of [his companion Yury] Yurkun should also never be ignored in assessing his response to the events of 1917.) The heroic spirit, the holiday atmosphere, and the air of euphoria he saw everywhere, especially on the ‘simple faces’ of the peasant soldiers crowding the streets, thoroughly seduced him.

Kuzmin chronicles this seduction in the poem ‘Russian Revolution’—as direct and “beautifully clear” an expression of his elation and great hopes as any diary entry. Unfortunately, Kuzmin’s hopes for a future free from oppression and fear—both as a writer and a member of a sexual minority—were not to be fulfilled. Yurkun was briefly arrested in 1918, in a wave of “Red Terror”, and continuously harassed by the police throughout the next two decades. And although Kuzmin himself continued to work as a theatrical composer, critic, editor and translator, his apolitical verse was rejected as non-Soviet; he withdrew into a small circle of friends and admirers, essentially living a life parallel to that of most of his countrymen, as if the Soviet Union simply did not exist. Conditions grew worse after Stalin came to power. In 1931 Yurkun was forced to become a police informant, while 1933 saw the official outlawing of homosexual activity, of which there had previously been no mention in the Soviet Russian criminal code. Kuzmin died of pneumonia on 1 March 1936, in the midst of the Great Purges, which would engulf many of his close friends, including Yurkun, who was arrested and executed in 1938.

Kuzmin had little time for the work of Sergey Esenin, a poet two decades his junior. Esenin was born into a peasant family in the village of Konstantinovo, near Ryazan. He received a solid education in a church-run school and left home for Moscow in 1912, supporting himself first by working in a butcher’s shop, then in a bookshop, then as a typesetter, and attending lectures at the newly opened Shanyavsky People’s University. He burst onto the literary scene after moving to Petrograd in 1915, where he associated himself with the New Peasant poets, growing especially close to their de facto leader, Nikolay Klyuev (1884–1937), who was openly homosexual; this was the first of many intense relationships Esenin—who was thrice married and had many affairs with women—would form with male poets.

Like the other New Peasants, Esenin wrote paeans to a glorified Russian countryside and the rural way of life, combining modernistic technique with folkloric imagery and devices drawn from traditional oral genres. In 1916–17, the peasant poets were championed by a group of intellectuals—the Scythians—who named their movement after a tribe of Iranian nomads that had occupied the area north of the Black Sea between the ninth century BCE and the fourth century CE. To their leading theoretician, Razumnik Ivanov-Razumnik (1878–1946), the spirit of the ancient Scythians—an Asian people on European soil—came to symbolize Russia’s special mission in the world: to reconcile the binary opposites of East and West, the rational and the irrational, the natural and the technological, the cultural forces of the common people and those of the intellectuals. With their radical blending of modern and traditional themes and modes, the New Peasant poets represented just such a reconciliation. The Scythians, who were closely associated with what would become the Left faction of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, were essentially romantic anarchists; they believed that a culture remains vital only if it is allowed to develop under conditions of absolute freedom, and they met both the February and October Revolutions with great zeal.

As men of peasant origin, Esenin and Klyuev could be expected to sympathize with revolutionaries who pledged land to the people and an end to the war. After all, in 1916 Esenin had only narrowly avoided being sent into battle—the fate of so many men of his class. Through the intervention of powerful friends, he was stationed at Tsarskoe Selo; he may have been a recognized poet, and had even met the empress, but he was still a peasant soldier—one of those “simple faces” that had won Kuzmin over to the revolutionary cause. Esenin’s poem ‘Wake me tomorrow at break of day…’ was his first poetic reaction to the events of February. Its vibrant imagery both is typical of New Peasant poetry and foreshadows the next step in Esenin’s literary career: his joining a movement called Imaginism, with a new close friend, the poet Anatoly Mariengof (1897–1962). Esenin’s ecstatic, apocalyptic poems of 1918 demonstrate a deep commitment to the Bolsheviks, drawing on Biblical and folkloric images of transfiguration and salvation.

Yet this commitment was always more emotional than ideological, and by the early 1920s it began to waver. A letter to his friend and fellow Imaginist Alexander Kusikov, written on 7 February 1923 from the deck of a ship on which Esenin was returning to Europe from the United States, testifies to the depth of his disenchantment: “I am ceasing to understand what revolution I belonged to. I can see only one thing—that it was neither the February nor the October, evidently. In us there was and is concealed a kind of November.” In his later work, Esenin mourns the demise of the Russian countryside, which had been ravaged by the Civil War and by early Soviet policy, and chronicles his own debauched lifestyle in Moscow’s taverns. The self-proclaimed “hooligan” became an idol for young nonconformists and a target of vicious attacks in the official press. He was found hanged in a Leningrad hotel room on 28 December 1925. Although he left a suicide note—a poem written in his own blood—many believe he was killed by the Cheka (the first incarnation of the Soviet secret police).

MIKHAIL KUZMIN (1872–1936)

Russian Revolution

It seems a century has passed, or just one week!

What week? A single day!

Saturn himself was shocked: his scythe

had never spun so quick.

A day before, people were huddled in a gloomy crowd,

jumping aside from time to time and shouting vaguely,

while the Anìchkov Palace fired volley after volley

over its traitorous shoulder in a red and vacant cloud.

News (so routine!) crawled by like snakes:

“Fifty… Two hundred killed…” Cossacks advance.

“They will not shoot!… Refuse…”

The governmental snitches hiss, their collars raised.

Today… Today the rising sun

saw all the gates swung open in the barracks.

No sentinels, policemen, pickets,

as if there never had been any guards or guns.

There’s music playing. Fighting’s broken out,

but, somehow—not the faintest hint of fear.

The troops have chosen freedom! God—my God!

Everyone’s ready to embrace each other.

Remember this—this morning, after that black night—

this sun, this polished brass.

Remember what you never dreamt would come to pass

but what had always burnt within your heart!

The news is ever gayer, like a flock of doves…

“The fortress has been taken! The Admiralty’s ours…”

The sky is clearer, bluer up above,