Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

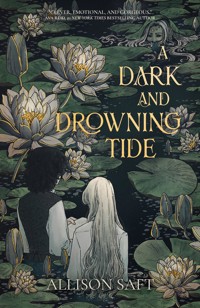

- Herausgeber: Daphne Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

A sharp-tongued folklorist and her academic rival must solve their mentor's murder in this lush sapphic fantasy romance from the New York Times bestselling author of A Far Wilder Magic. Lorelei Kaskel, a folklorist with a quick temper and an even quicker wit, is on an expedition with six eccentric nobles in search of a fabled spring. The magical spring promises untold power, which the king wants to harness to secure his reign of the embattled country, and Lorelei is determined to use this opportunity to prove herself and to make her dream come true: to become a naturalist, able to travel freely to faraway lands. The expedition gets off to a harrowing start when its leader—Lorelei's beloved mentor—is murdered in her quarters aboard their ship. The suspects are her five remaining expedition mates, each with their own motive. The only person Lorelei knows must be innocent is her long-time academic rival, the insufferably gallant and maddeningly beautiful Sylvia von Wolff. Now in charge of the expedition, Lorelei must find the spring before a coup begins and the murderer strikes again. But there are other dangers lurking in the dark: forests that rearrange themselves at night, rivers with slumbering dragons waiting beneath the water, and shapeshifting beasts out for blood. As Lorelei and Sylvia grudgingly work together to uncover the truth—and resist their growing feelings for one another—they discover that their professor had secrets of her own. Secrets that make Lorelei question whether justice is worth pursuing, or if this kingdom is worth saving at all.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 555

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Part I: The Yeva in Thorns

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Part II: Blood in the Water

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Part III: The Vanishing Isle

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Part IV: The Source

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Acknowledgments

About the Author

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

First published in the UK in 2024 by Daphne Press

www.daphnepress.com

Copyright © 2024 by Allison Saft

Cover and edge illustration © 2024 Erica Williams

Cover design by Jane Tibbetts

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This edition is published by arrangement with Del Rey, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-83784-061-8

Illumicrate Hardback ISBN: 978-1-83784-060-1

Waterstones Hardback ISBN: 978-1-83784-088-5

eBook ISBN: 978-1-83784-062-5

1

FOR MOSES, GILBERT, AND ALEXANDER

Part I

The Yeva in Thorns

One

SYLVIA WAS IN THE river again. Lorelei didn’t need to see her to be certain of it. Crowds, after all, were the smoke to Sylvia’s fire.

Lorelei stood with her shoulders hunched against the wind, trying and failing to contain her mounting disgust. In the span of an hour, the entire student population of Ruhigburg University had spilled onto the banks of the Vereist. They clamored and shoved and jostled one another as they fought for a better view of the water—or, perhaps more accurately, the spectacle they’d been promised. Most of them, predictably, were nursing a bottle of wine.

As she approached the edge of the crowds, she saw silver glittering on throats and iron chains jangling on wrists. They wore their jackets inside out and strung horseshoes around their necks. A few—Sylvia’s most avid devotees, no doubt—had crowned themselves with rowan branches and braided clover into their hair. They clearly expected blood. Lorelei had never seen so many protective wards in her life.

Utterly ridiculous. If they truly wanted to guard themselves against fairy magic, they should have stayed well away from the river instead of gawping at it like nitwits. She supposed she shouldn’t be surprised. Good sense tended to flee wherever Sylvia von Wolff went.

Apparently, some poor fool had nearly drowned an hour ago—lured into the abyssal depths of the river by an errant nixie’s song. It was almost impressive, considering a nixie hadn’t been spotted this close to the city in ten years. She’d overheard a girl regaling her friends with the gruesome details—and then, nauseatingly starry-eyed: “Did you hear Sylvia von Wolff has promised to tame the nixie?”

Lorelei had nearly combusted then and there.

Professor Ziegler had asked Lorelei and Sylvia to meet her fifteen minutes ago. Tonight, the king of Brunnestaad himself was hosting a send-off ball in honor of the expedition, and the three of them were meant to make a grand entrance: the esteemed professor and her two star students. If they made Ziegler late . . .

No, she could not even think of it.

Lorelei shoved into the crowd. “Move.”

The effect was instantaneous. One man dropped his opera glasses as he leapt out of her path. Another yelped when the hem of her black greatcoat brushed his leg. Another less fortunate soul stumbled forward as Lorelei’s shoulder clipped hers.

As she passed, someone behind her muttered, “Viper.”

If she had any time to spare, she might have risen to the bait. Every now and again, people needed to be reminded of exactly how she’d earned that name.

She elbowed her way to the front of the crowd and scanned the riverbank. Even beneath the pale light of dusk, the waters of the Vereist remained an eerie, lightless black. It cut straight through campus like an ink stain that wouldn’t lift. And there, shrouded in the branches of a weeping willow, was Sylvia.

From this angle, Lorelei couldn’t see her face, but she could see her hair. Even after five years of knowing her, it always shocked her—the stark, deathlike white of it. She’d knotted the unruly waves at the nape of her neck with a ribbon of blood-red silk, but a few stubborn strands had managed to escape. In Lorelei’s weaker moments, she imagined that grabbing hold of it would feel like plunging her hands into cold water.

She stalked toward Sylvia, and with as much acid as she could muster in two syllables, she said, “Von Wolff.”

Sylvia gasped, whirling around to face her. As soon as their gazes met, Sylvia’s face paled to the enchanting color of soured milk. Lorelei allowed herself one moment to delight in that glimpse of startled dread before Sylvia’s perfectly pleasant mask slotted back into place. Somehow, after all this time, Sylvia had never grown accustomed to being hated.

And oh, how Lorelei despised her.

“Lorelei!” Her pained smile dimpled the dueling scar slashed across her cheek. “What a pleasant surprise.”

Sylvia sat on the riverbank, her feet dangling in the water and the skirts of her damask gown puddled around her. Her mud-caked slippers lay abandoned beside her, and she cradled—of all things—a guitar in her lap.

The beginnings of a tension headache pounded in Lorelei’s temples. She felt as though she’d suddenly lost her grasp of the Brunnisch language—or perhaps been transported to some stranger realm where one could reasonably face down one of Brunnestaad’s deadliest creatures in full dress. Then again, Sylvia looked as though she’d gotten ready in a great hurry and then gone traipsing through the woods. She very well might have, if the stray petals tangled in her hair were anything to go by. Cherry blossoms, Lorelei noted absently. Spring had come early this year, but a damp cold lingered like a fever that wouldn’t break.

“You’re late.”

Sylvia had the good sense to wince, but she continued tuning her guitar. “I am sure Ziegler will understand. You’ve heard about the nixie attack, haven’t you? Someone had to do something about it.”

Lorelei felt her entire body seize with murderous intent. “That doesn’t mean it had to be you, you arrogant fool.”

Sylvia reeled back, affronted. “Excuse me? Arrogant?”

Lorelei glanced pointedly at the crowds behind them—at the hundreds of eyes trained on Sylvia. Lorelei could nearly taste their hunger in the air. Whether they truly wanted to see Sylvia work her strange magic or to watch her blood run into the water, Lorelei did not know. She supposed it didn’t matter. Either way, they’d have gotten what they came for.

“Insatiable, then.” She sneered. “You’ll have a legion of well-wishers to fend off in a matter of hours, and yet you’re starved for attention.”

Bitterness crept unbidden into her voice. Six months ago, Ziegler promised to name one of her students the co-leader of the Ruhigburg Expedition, and tonight, she would finally announce her selection at the send-off ball. Lorelei had never harbored any expectation that she’d be chosen. At twenty-five years old, Sylvia was one of the most famous and beloved naturalists in the country. And Lorelei was no one, a cobbler’s daughter plucked from the Yevanverte.

Even so, she dreamed.

With that kind of renown, any publisher would leap at the opportunity to print her research. Even better, it would force the king to acknowledge her. Past rulers had only kept Yevani in their court as bankers and financiers, but King Wilhelm surrounded himself with artists and scholars. Lorelei was not beautiful enough to whisper her heart’s desires into the king’s ear and believe he would listen. There was no charm she had, no power she possessed to make her persecutors throw themselves at her feet. All she had was her mind. If she co-led the expedition he’d commissioned, she’d have the sway to ask him to appoint her a shutzyeva: a Yeva under the direct protection of the king.

She’d learned to survive the viper pit of Ruhigburg University by becoming the worst of them. But outside the university, her reputation meant nothing. As a shutzyeva, she would be granted the full rights of a citizen. She could exist, unbothered and untouchable, outside the walls of the Yevanverte. With a direct line to the king, she could advocate for her people. But her most secret, selfish desire was simple. As a citizen, she could purchase a passport, her ticket to a world she’d only ever read about. It was all she’d ever wanted, the only thing she’d ever allowed herself to want: the freedom to be a real naturalist.

Wilhelm had not appointed any shutzyevan during his brief reign. But it was an exceedingly rare honor—one she was certain she could earn.

“I am not doing this for attention.” Sylvia looked flustered. “I’m doing this for—”

“What you’re doing is wasting everyone’s time,” Lorelei said brusquely. She had endured far too many speeches about noblesse oblige over the years to let Sylvia continue uninterrupted. “Mine, Ziegler’s—and His Majesty’s, for that matter. You’ve spent far too long playing knight-errant with your own research. It’s high time you took your responsibility to the expedition seriously.”

Sylvia’s face flushed, and her pale eyes filled with fire. It made Lorelei’s blood quicken with anticipation and her mouth go dry. “Accuse me of neglecting my duties to Wilhelm again, and I will pitch you into the Vereist.”

Lorelei knew she’d touched a nerve. Most provinces had resisted the unification of their patchwork Kingdom of Brunnestaad—and none fought more valiantly than Sylvia’s homeland of Albe. Even twenty years after their annexation, they agitated for their independence. Lorelei supposed she could sympathize. They practiced their own religion, spoke their own dialect, and by land mass rivaled the rest of Brunnestaad combined. The rest of the kingdom believed them heretical, mountain-dwelling yokels, ready to turn and bite at a moment’s notice. Sylvia, naturally, was the heir apparent to its ducal seat.

“Besides,” Sylvia continued huffily, “this will be fast. I know exactly how to deal with nixies by now.”

Lorelei had never seen a nixie before, but as the expedition’s folklorist, she had recorded countless tales of the wildeleute over the years. Most commoners she’d interviewed thought them monsters, sometimes even gods. In truth, most species of wildeleute were nothing but a nuisance. The more bearable sort sequestered themselves in far-flung places and amused themselves by leading travelers astray. Others ran amok in the countryside, stirring up mischief in villages and trading petty enchantments for bread crusts or jars of cream.

And then, there were creatures like nixies. Facing one armed with only a guitar and three kilos of silk seemed to Lorelei a regrettable idea. “And how, exactly, do you plan to deal with it? Bludgeon it? Perhaps invite it to tea?”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Sylvia replied crossly. “I am going to sing to her. I’ve been practicing my technique for months now.”

“Sing to it?” Lorelei spluttered. “That is the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard.”

Sylvia canted her chin. “And how many books have you published on the subject of nixies?”

A frigid silence descended. Both of them knew very well that Lorelei had not published a word.

“Mock me all you’d like,” said Sylvia, “but my research suggests that nixies congregate around sources of magic. Learning to communicate with them could prove invaluable on the expedition.”

Lorelei very much doubted that. Debates still raged in the halls of the university about the exact origin and nature of magic, but the most widely accepted theory posited that it was aether, a natural substance found only in water. Thaumatologists, specialists in the study of magic, had already developed instruments to measure it, and those were far less deadly and far more precise than nixies, of all things.

Feeling spiteful, she gestured at the empty expanse of the river. “Well, then, let us see your groundbreaking research in action. Or have nixies learned to cloak themselves as well as alps?”

The crowd was growing restless. Farther upriver, she spied a group of boys shouting and jeering as they hefted one of their friends into the air. Clearly, they meant to throw him into the river. Lorelei rolled her eyes. There was a reason no one swam in the Vereist. Once you sank beneath the surface, there was no way to orient yourself in the total darkness. Nixie or not, someone was going to die today.

Sylvia flushed with indignation. “She will come.”

“Go on, then. Far be it from me to distract you.”

Sylvia smiled beatifically. “Wonderful! Then please be quiet.”

Lorelei had half a mind to shove her into the river, but she complied.

Sylvia plucked an off-key little arpeggio, and then began to sing. Lorelei watched her from the corner of her eye. The evening light filtered through the branches overhead, casting lacelike shadows across Sylvia’s face. She grinned as her fingers clumsily shaped the chords. Never in Lorelei’s life had she encountered anyone so demonstrative. She’d spent most of her life around northerners and had grown accustomed to their cold, clipped efficiency. But in Albe, people did strange things like sing in public and—worse—hug one another in greeting. Most of the time, Sylvia’s easy warmth and excitability infuriated Lorelei. Other times, it reminded her too much of all the things she’d left behind.

She tore her gaze away and tightened the stranglehold on her own homesickness. Out in front of her, the Vereist shone like a sheet of black glass. It had always unsettled her, but it was far from the strangest river in Brunnestaad. To the north, there was the Salz, where you could step onto its churning surface and walk straight across from bank to bank. To the west, you could wade into the Heilen and your every wound would close. And somewhere in this treacherous, sprawling kingdom lay the aim of the Ruhigburg Expedition: the Ursprung, the fabled source of all magic and King Wilhelm’s current obsession.

Sylvia grabbed her arm. “Look!”

Before Lorelei could twist out of her grasp, the water rippled. Slowly, something emerged from the darkness of the river. The mist parted, and a gaunt face stared out at them, as gray and lustrous as a full moon against the clouds.

Gasps and shouts rang out from the crowds behind them. Lorelei couldn’t find it in herself to be annoyed. There was, admittedly, a certain provincial novelty in seeing one of the wildeleute here in the city, as if some folktale or quaint landscape painting had come to life. All of the engravings in the travel narratives she’d read paled in comparison to the sight of her, real and solid and terrible. The nixie’s skin glistened, and her dark hair fanned out atop the river like a spill of ink. But her eyes struck Lorelei with a cold, instinctual dread. They were a solid black as depthless as the Vereist—and uncannily reptilian; a thin, translucent film slid over them as she blinked.

“Look at her,” Sylvia said with true wonder in her voice. “Isn’t she magnificent?”

No, Lorelei wanted to say. She’s dreadful.

A glittery sound caught Lorelei’s attention. A tangle of pendants rested against Sylvia’s collarbone, each one engraved with the icon of a saint. Lorelei could not recall the last time she’d seen her without them; they’d always struck her as unusual. Here in the province of Neide, non-Yevani tended to be more restrained in their faith. But Sylvia, Albisch through and through, prayed as ostentatiously as she did anything else. She unclasped them one by one until they lay in a heap beside her. Just like that, she carried no wards that might whittle the edges of the nixie’s magic.

Despite herself, Lorelei understood the morbid fascination of the crowd. She’d never watched Sylvia work before. Admittedly, there was a sick sort of thrill that came from watching someone hurl themselves headlong into danger. In recent years, Sylvia had made a name for herself due to her . . . unusual methodology. She published trivial little stories of her adventures with the wildeleute, ones in which she purposefully ensnared herself in fairy magic in order to record the experience. Her travelogues enraptured her readers—bamboozled them into calling her a visionary. But there was no scientific merit to them whatsoever. They were an affront to empiricism, based on threadbare anecdotal data and—worse—whimsy. Lorelei knew by now that Sylvia was only exceptionally lucky—and incredibly stupid. A nixie’s song held a powerful hypnotic magic; countless had drowned under their spell.

The nixie eased herself onto a smooth rock jutting from the river’s surface, and Lorelei did her best not to recoil. The nixie’s hair was tangled with lotus flowers and as slick as a knot of cattails. It cascaded over her bony shoulders and pooled in her lap. Where a human’s legs would begin, her hips were covered in iridescent scales and tapered into a long, serpentine tail. Her blue lips parted just enough to reveal the barest glimpse of her serrated teeth. It was a smile that sent a bolt of fear straight through Lorelei.

“Von Wolff,” Lorelei warned.

“Peace, Lorelei.” The fact Sylvia sang it only added insult to injury. “She’s just curious.”

She hardly saw how that was reassuring. A clamor went up behind them. Lorelei glanced over her shoulder to see that their audience had grown in number—and grown bolder. They pressed in closer, chattering excitedly and pointing.

Idiots, all of them.

“Get back,” Lorelei snapped, “unless you want to drown today.”

A hiss pulled her attention back to the water. As the nixie drew in a breath, the membranous gills on her rib cage rippled and flared. Then she began to sing, and all the world went perfectly still.

It was a song like the sea—the sweetest song Lorelei had ever heard. It swelled and crested, inexorable and irresistible as it wove around Sylvia’s in perfect harmony. One moment, Lorelei had her feet planted solidly on the earth. The next, she felt weightless, soaring. Never before had she felt so . . . complete, as though she breathed in tandem with every being on earth. For one glorious, incandescent moment, she saw it: the vibrant, wild beauty of the world. Aether was within all of them—withineverything. It glimmered in the mist, and the Vereist sparkled with a thousand different colors, so bright it nearly brought tears to her eyes. How had she ever thought it so dark?

She took one step toward the water, then another. Just as she toed the edge of the riverbank, the iron chain around her neck singed her, as though she’d touched a white-hot brand. With a gasp, Lorelei snapped back to her senses. The river—once again black and dull as iron—churned winkingly below her. She nearly swore aloud. If she didn’t get herself together, she was going to drown in shallow water like a doddering fool.

Focus, damn you.

She bit down on the inside of her lip. As the tang of copper coated her tongue, the nixie’s magic dissipated completely. A horrid keening cut through the haze of her thoughts and set her blood to ice.

So that was the true sound of its song.

Sylvia, however, remained under its enchantment. She stood perfectly still, with a strange and shining look of rapture in her eyes. It was a rare thing to examine her up close, when she was always in motion. Her eyes were a shade of gray so pale they were almost violet. Like most of the nobility, she had a fine latticework of dueling scars across her temples: each one a dubious badge of honor for enduring a blow to the face. The thickest one, gashed across her cheek, shone like a sheet of sunlit ice. Sylvia set down her guitar, still humming her eerie, tuneless song. The noise of the crowd swelled once again.

Somewhere in the din, Lorelei could make out someone shouting, “She’s doing it!”

A bolt of alarm shot through Lorelei. “What are you doing?”

Sylvia ignored her as she walked toward the river. The loose ends of her hair danced in the wind, the last red glare of the day illuminating it like white fire. The nixie extended a webbed hand to her. As Sylvia waded toward her, it was all too easy to imagine her slipping under. Her fine plum gown would bloom around her like a rose. Her silver hair would be stark as bone against the deep black of the river. Alas, Ziegler would never forgive Lorelei if she sat idly by while their naturalist waded to her death. She would have to intervene.

As a rule, Lorelei didn’t use her magic where anyone might see. But over the years, she’d grown adept at concealing it. Inhaling deeply, she called on her magic. Power unfurled through her chest and flowed down to the tips of her fingers. She imagined closing her fist around the aether rushing through the water, and—there. There was a brief moment of overwhelm, when her will pulled uselessly against the river. But then the connection snapped into place, and she felt the Vereist like an extension of herself, a phantom limb. Its current roared in her ears like the flow of her own blood. Sweat beaded on her brow. She didn’t have long before she lost her hold on it entirely, but she didn’t need much.

With an exhale, she sent the water skipping off its course—just enough to sweep the nixie from her perch. Sylvia jerked like her strings had been cut. At last, Lorelei let go of her magic. Relief and exhaustion settled heavily over her.

The nixie shot out of the water a moment later, fixing Lorelei with a look almost like indignation. With a toss of her hair, the nixie slipped back beneath the surface and disappeared. It was so startlingly human, it left Lorelei dumbfounded.

“Wait!” Sylvia called helplessly.

So help her, if Sylvia tried to pursue that beast . . .

Before she could think better of it, Lorelei closed the gap between them and took hold of her elbow. “Have you lost your mind? Get back here now.”

Sylvia rounded on her with her mouth hinged open, no doubt to say something petulant and irritating, but Lorelei didn’t get a chance to hear it. Sylvia wrenched her arm away so vehemently, she lost her footing—and took Lorelei with her. For one horrible moment, time seemed to grind to a halt. The sounds of shrieks reached her from a thousand kilometers away.

Then, they toppled into the water.

Blackness enveloped her, so complete she couldn’t see her own hand in front of her face. The cold greedily snatched her breath away. Lorelei kicked her way to the surface and gasped in a lungful of air.

Sylvia had already crawled onto the shore, looking very much like a wet cat. She bristled, her dress clinging to her skin, her hair limp around her shoulders. The gathered masses had already begun to scatter, disappointment plain on their faces.

“Look what you’ve done now,” Sylvia said accusingly. “She was speaking to me.”

“What I’ve done?” It was hard to feel especially righteous with her hair plastered to her face. Her mouth tasted like river water and silt. She somehow managed to overcome the weight of her sodden greatcoat and hauled herself onto the riverbank. “That was entirely your fault.”

Sylvia jabbed a finger at Lorelei’s face. How absurd, that someone a full head shorter than Lorelei was attempting to menace her. “I was perfectly in control of the situation. You’ve made me look like a fool.”

“You do a good enough job of that on your own.” Lorelei pulled her watch from her breast pocket. “We need to hurry if . . .”

The second hand tick, tick, ticked feebly in place, broken. The minute hand had met its untimely demise, fixed eternally at five minutes past their scheduled departure time.

They were going to be late, and Ziegler was going to murder them.

Two

WHEN THEY FINALLY ARRIVED at the meeting point, there was nothing left to say. Lorelei had wrung every ounce of vitriol she could from the Brunnisch language and then some in Yevanisch. Sylvia had endured it all with a spitefully martyred expression and now kept her sullen silence.

Ziegler leaned against the carriage, radiating palpable malcontent. As they approached, she fixed them with a flat, unimpressed stare.

“Get in,” Ziegler said, and climbed into the carriage.

Obediently, they followed her. Lorelei took the seat opposite Ziegler. Sylvia, infuriatingly, settled in beside Lorelei and adjusted the sodden train of her gown. Lorelei clenched her jaw to keep her teeth from chattering.

The river had washed the starch out of her shirt, and somehow, that enraged her as much as their tardiness. She could not afford vanity, but this was a matter of respectability—oforder. She had fastidiously knotted her cravat, and her collar points had once cut a strong, sharp line across her jaw. Both, now, were limp and sad. Worse still was the awful sensation of wet fabric against her skin. Sylvia, meanwhile . . . Even half-drowned in a mud-stained gown, she managed to look fairy-tale beautiful, as perfect as a princess in a glass coffin. When Lorelei looked at her, she felt sick with an emotion she preferred not to name.

Long ago, a seed of bitterness had taken root within Lorelei. Over the years, it had grown wild and sprouted thorns that coiled around her heart. She didn’t envy Sylvia, exactly; she had never wanted to be beautiful. Still, it sometimes stung that she couldn’t even claim to be conventionally handsome—or at least classically Brunnisch, with fair hair and pale blue eyes. She’d cut her dark curls short, save for an unruly spill over her forehead, the style fashionable with most gentlemen. But with her sharp cheekbones and aquiline nose, she looked severe and dour rather than rakish, an effect that wasn’t softened when she spoke.

At last, as the carriage began to move, Ziegler opened fire. “Do you care to explain why you’re late?”

Oh, would she ever. Lorelei sat up straighter. “I—”

“Or why you look like drowned rats?”

Sylvia wilted. “Well—”

“Or why you’ve chosen to spite me on today of all days?” With every question, her voice grew more strident, her words quicker.

“If you’d just—”

“What part of ‘all of our careers depend on the expedition’s success’ was difficult for you to understand?” It took a moment for Lorelei to process she’d begun speaking in Javenish. Ziegler had spent most of her adult life in Javenor before the previous king summoned her home some fifteen years ago. She’d returned bitterly, but in many ways—her affected Javenish accent, her disdain for all things Brunnisch—she acted as though she’d never left. “Do I need to put it more plainly?”

When neither of them answered, she said, “Well?”

“No?” Sylvia tried.

“No? Then why are you trying to sabotage it? Showing up this late—and with you two in such a state—is a complete and utter embarrassment!”

“He and I are old friends,” Sylvia said miserably. “He has seen far worse, I assure you.”

“And I’ve been advising politicians longer than you’ve been alive,” Ziegler countered. “This event is meant to communicate stability. Unity. Confidence. How do you think it will look when his most credible political rival strolls in as though it’s a joke to her?”

“I am not interested in being his puppet!”

“Too bad. Tonight, we all are.” Ziegler slouched deeper into her seat and crossed her arms. She looked somewhere between defeated and disgusted, with her steely glare fixed out the window. “I don’t care how long you’ve known the man or how good-natured he is. None of that means a thing if he feels the stability of his reign is in jeopardy.”

It was a fair point. No man secure in his reign would waste resources seeking the Ursprung. Few people believed it existed outside the realm of fairy tale.

Most people had some ability to wield magic. The most skilled practitioners could pull moisture from the air or freeze the surface of a pond with a wave of their hand. But the Ursprung—if you were willing to pay the price, of course—granted incredible power. The folktales Lorelei had compiled over the years could never seem to agree on how exactly it worked or what horrible fate awaited whoever sought its power.

“Fifteen years,” Ziegler said with palpable resentment. “Fifteen years the royal family has kept me in the palace on a gilded chain. Finding this damn spring is the very last service I owe him.”

Once, Ziegler had undertaken years-long expeditions and spent her off-time in a well-appointed flat in the most fashionable city in Javenor. Now she served as Wilhelm’s chamberlain, a role she resented but could not escape. He called her his walking encyclopedia.

More like his dancing monkey, Ziegler often groused.

“I need open air. I need interesting people,” she continued. “I have worked far too hard on this for you two upstarts to ruin it for me.”

Upstarts. It stung more than Lorelei expected. Of course, Ziegler did not truly mean it; she often lashed out in a temper. Even so, Lorelei could not help feeling like the broken twelve-year-old girl she’d been when Ziegler first took her under her wing: as desperate to please as she was to escape.

“This is entirely von Wolff’s fault.” Lorelei hated the petulance of her own voice, but she could not stop herself. “I was on time.”

Sylvia shot her a mutinous look. “I was testing a theory that will prove invaluable—”

“Enough. You’re giving me a headache.” Ziegler pinched the bridge of her nose and heaved a long, exasperated sigh. “I can’t bear to look at either of you right now.”

A hot rush of shame struck Lorelei first. But as she stared at Sylvia, it was consumed by a steady, burning hatred. Nothing was safe. Not her pride, not her position, not even the affection of their mentor. By the time they graduated, Sylvia von Wolff would take everything from her.

Lorelei angled herself sharply toward the window and stared out at the passing city. As the sun settled like a banked coal on the horizon, it occurred to her that it was the eve of the day of rest. Her parents and younger sister, Rahel, would soon be making their way to the evening service. Lorelei couldn’t remember the last time she’d prayed, or when exactly she’d stopped feeling guilty about it. Even so, she couldn’t tamp down the longing that rose within her when she saw the temple’s spires reaching out of the gloom.

She missed the bustling hours before sundown, how her family would cook and clean as if about to welcome the king himself to their home. She missed the soothing rhythm of her father’s voice as he blessed their wine at dinner, the sweet scent of braided bread. Sometimes, she even missed the interminable morning services. Lorelei didn’t mourn her faith, only the girl she was before she met Ingrid Ziegler—the girl who still belonged in the Yevanverte. Every night, she returned to her family more a stranger than the last: more Brunnestaader than Yevanisch.

They never said anything, of course, but Lorelei was not oblivious. She saw how it pained them when she spoke to them in Brunnisch without thinking, or when she couldn’t recall which of their neighbors’ children had gotten married last month, or when she burned another candle down to nothing, working long after everyone had gone to sleep. Still, she awoke each morning to tea and a slice of apple cake on the table. She came home every night to a place set for her at the dinner table. She endured all of their needling about her well-being and happiness and marriage prospects. Even if they no longer understood her, they loved her. If only she could say she was doing all of this for them.

Someday, maybe, they’d benefit from her selfishness.

Soon, the royal palace rose before them. She had only ever seen it from a distance: a pale smear on the other side of Ziegler’s lonely office window. Up close, it was an ostentatious sprawl of white stone crowned with a dome of copper. The moon seemed to balance on its tallest peak, silvering the gardens with a soft hand. The air was thick and sweet with the scent of roses. Thanks to the king’s veritable army of royal botanists, they blossomed in every imaginable color, from dusky gold to purest white. But it was their thorns that Lorelei most admired, each one a bolt of silver in the dark.

The coachman brought them to a stop at the end of a line of carriages. A footman rushed to help Sylvia down from the carriage. Rolling her eyes, Lorelei shoved open her own door.

Another footman appeared at her side. Before he could open his mouth, she snapped, “Don’t touch me.”

Together, the three of them ascended the palace’s marble staircase. The doors looming over them might have been awe-inspiring were they not so utterly tasteless. The wood paneling was inlaid with gold, and the lintel was ornately carved with—of all things—nixies rising from sea-foam. Sylvia, to her credit, said nothing of it.

When she’d imagined herself walking through those doors tonight, it was a triumph: the end of a long and brutal road. She would’ve been greeted by the king himself. She would’ve been introduced to the most esteemed naturalists in the country. The reality was worse than anything she could’ve conjured herself.

Without a word, Ziegler thrust their invitations toward the doorman, who scanned first the invitations, then their faces, with something resembling judgment. “Welcome.”

When he opened the doors, the sounds of conversation and laughter spilled out. Clearing his throat, he called, “Herr Professor Ingrid Ziegler, leader of the Ruhigburg Expedition; Miss Sylvia von Wolff, naturalist of the Ruhigburg Expedition; and Lorelei Kaskel, folklorist of the Ruhigburg Expedition.”

It was as though he’d dropped a bell jar over them. Every sound suddenly grew muffled and indistinct. Some were amused, others clearly suffered from secondhand embarrassment, and still others were deeply unimpressed. Lorelei felt like a specimen pinned on a naturalist’s table, open for dissection.

She must have been scowling, because Sylvia leaned in and jammed an elbow into her ribs. Lorelei managed a rictus of a smile, which caused the nobleman closest to them to shrink back as though she’d thrown hot oil at his feet.

“Good evening!” Sylvia said, too sunnily to be entirely convincing. “Thank you so much for coming tonight.”

Just like that, the spell broke. Conversation resumed, the music soared high above them, and Lorelei took the opportunity to vanish into the crowds.

The dazzle of the chandeliers and the incessant drone of the crowd plucked at the headache she hadn’t quite shaken. A good night’s sleep would set her straight, but she couldn’t help feeling irritated with herself. She shouldn’t have used magic so frivolously—or recklessly, for that matter. Magic always drained its channeler; how much depended on the volume and speed of the water, as well as the channeler’s proficiency. By all accounts, she shouldn’t have attempted what she did, but that hungry, dangerous look in the nixie’s eyes had awakened some selfless impulse within her. Lorelei bit down on a furious groan.

Next time, she’d let Sylvia wade to her own pointless death.

She kept her chin lifted as she navigated through the press of bodies. Among all this finery, she was remarkable in her unremarkableness. She had dressed, as she usually did, in black. Her mother had insisted on taking the jacket to the tailor, who had embroidered the lapels and cuffs with roses in glossy black thread. Lorelei now wished she hadn’t given in. The ruined extravagance of it embarrassed her even more than her dishevelment—and it wasn’t as though she had anything to celebrate tonight.

It took her no more than a minute to locate the far-flung corner where the rest of the unsociables lurked. She had gotten this far. She had no dignity or expectations left to shatter. All there was to do now was survive until the end of the night. When a servant passed with a silver platter of wine flutes, she took one and immediately swilled it.

“Kaskel,” said a familiar voice.

As if her evening hadn’t been ruined enough.

She turned to find Johann zu Wittelsbach, the expedition’s medic and future duke of Herzin, standing there in full military dress. Half his hair was pulled back from his face, and the rest tumbled down to his shoulders in a spill of gold. He wore a ceremonial saber and an expression that suggested he was both surprised and affronted to find her here.

The feeling was quite mutual.

“Johann,” she said curtly. “You’ve obviously come here for some good reason. What is it?”

“Hostile,” he noted. “I’m here to keep an eye on you.”

“And what have I done to warrant scrutiny?”

He drew near enough that he loomed over her, but Lorelei held her ground. This close, she could smell liquor on his breath. It made her skin crawl with half-remembered dread. Alcohol and men like Johann never mixed well. It emboldened them.

Beneath his spectacles, his eyes were a flat, glacial blue. “You’re here.”

She understood very clearly what he left unsaid: And you shouldn’t be, filthy Yeva. Tamping down her anger as best she could, Lorelei said, “By His Majesty’s invitation.”

A flicker of annoyance passed over his face. “An oversight on his part. Wilhelm has always had the unfortunate tendency to see the best in others.”

Lorelei supposed he would know. He and the rest of the expedition crew—the Ruhigburg Five, as they were known around campus—had spent their childhood summers together, running wild in these very halls. They had all the squabbles and half-buried resentments real siblings did. All of them were in their mid-twenties, but she’d come to understand Johann had taken on the role of the oldest: a bully or a protector, depending on his mood.

No good would come from provoking him. But she’d been worked into too much of a temper to stop herself. “How fortunate he is to have such a well-trained guard dog.”

His eyes grew flinty as he registered her mockery. “I know how you intend to repay his hospitality.”

“And how is that?” she hissed.

He gave her an unkind smile of his own. That was answer enough.

As if on instinct, her gaze dropped to the chain around his neck. From it hung a roggenwolf’s fang cast in silver: the symbol of a now-defunct holy order known as the Hounds. They’d gotten their start hundreds of years ago, hunting dangerous wildeleute (or demons, as they called them) with blessed silver. But a few decades back, they’d aimed to cleanse Herzin of “vermin”: people like Lorelei—and people like Sylvia, whose aberrant religious practices corrupted the spiritual purity of their territory. When Johann took power from his father, she did not imagine it would take them long to return.

“I’ve been watching you for a long time, Kaskel. I’ve seen the extent of your scheming, grasping ambition.” He bent down and murmured, “I look forward to seeing it thwarted tonight.”

With that, he walked away.

Lorelei could only watch him go with impotent rage boiling within her. Nothing about his behavior surprised her. She’d once checked out Johann’s first book from the library—and promptly returned it after reading the phrase “those from a superior branch of humanity are morphologically better adapted for channeling aether” halfway down the first page.

Since then, she’d never taken him seriously as a scholar. Contrary to the ridiculous taxa of humanity he and his ilk had developed, Yevani could use magic.

The first time Lorelei had done it, her father had struck her. It was the very first time he’d done so—and the last. For a moment, she’d only been able to stare up at him with her ears ringing. He gazed back at her in horror, pale and trembling. When he’d finished apologizing and dried both of their tears, he knelt at her feet and cradled her face in his hands.

You must never do that, he said, where any of them can see. They believe us powerless. It upsets them to see proof otherwise. Do you understand?

Even then, she did. Now she only wondered if her obedience had cost Aaron his life.

The way the candles’ flames refracted through the crystal chandeliers gave the whole room the impression of being underwater. From her vantage point, she could see all the hollow splendor laid out before her. Partygoers chilled their drinks with an absent touch and wicked sweat from their brows with a thoughtless flick of their fingers. Beads of ice glittered cold as stars on the hems of their jackets, and mist billowed around the trains of their gowns. Magic truly meant nothing to these people.

Past the glittery whirl of skirts and tailcoats, Lorelei spied Ziegler speaking with Sylvia’s mother, Anja von Wolff. Unlike her daughter, the duchess was a slip of a woman: frail-boned, hollow-eyed, and deathly pale. There was no resemblance between them but the determined set of their jaws; it seemed Sylvia had not inherited the bone white of her hair from her mother.

What business could they possibly have with each other? Ziegler often advised politicians on matters of land conservation and colonization, of which she was a strong and vocal opponent, but Anja von Wolff was known for her military strategy, not her curious mind.

Lorelei’s curiosity outweighed her self-preservation enough to watch. As they spoke—or perhaps argued—Anja jabbed a finger at Ziegler. Despite herself, Lorelei felt a twinge of sympathy at how familiar that gesture was. Sylvia had inherited something from her mother, after all.

Her message clearly delivered, Anja turned on her heel and slipped into the crowds. Ziegler stood dumbfounded for a moment. Then, as if Lorelei had called her name, she met her gaze from across the room. Her surprise melted into something entirely unreadable. After a moment, she looked pointedly away, as if they were no more than strangers.

Before disappointment could truly sink in, tinkling laughter sounded from beside her. “Poor Lori. You’re like a spaniel that’s still surprised when it’s kicked.”

Heike van der Kaas: the expedition’s astronomer, the cosseted heiress of the seaside province of Sorvig, and widely rumored to be the most beautiful woman in Brunnestaad. When confronted with her deep-red hair and striking green eyes, it was difficult to dispute. Lorelei, however, had never been able to look past her petty cruelty.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” she said.

“There’s no need to be strong for my sake.” Heike fluttered an ivory-boned fan in front of her face. “If Ziegler’s upset with you, that doesn’t bode well for the announcement, does it?”

“What does it matter to me?” Lorelei asked coolly. “It was never a competition.”

Not one she ever expected to win, at any rate.

“Well,” Heike said, clearly disappointed she had not gotten a rise out of her. “I’m still holding out hope for you, if only to see the look on Sylvia’s face.”

By now, the genuine spite in Heike’s voice did not surprise Lorelei. Over the months the crew had been preparing for the expedition, Lorelei had watched countless rifts form and mend among the group almost day by day. But whatever tension simmered between Heike and Sylvia had the air of something old and unforgiven, like a bone that had never set quite right.

After a pause, Heike leaned in conspiratorially. “And Johann’s, for that matter. Could you imagine him taking orders from you? How I’d laugh.”

Lorelei had endured far too many insults today to let it go unpunished. Before she could think better of it, she said, “I’m holding out hope for you as well.”

Heike’s coy smile faltered. With venom, she said, “How sweet of you.”

For almost two years, each member of the crew had been conducting their own expeditions in order to collect data for Ziegler—data she’d use to pinpoint the general location of the Ursprung. After twelve years of knowing her, Lorelei understood the theory well enough. The density and types of flora, the behavior of the wildeleute, even the number of magic users in a given population . . . All of it was correlated with the concentration of aether in nearby bodies of water. If the Ursprung was indeed the source of all magic, all they had to do was follow the data like a breadcrumb trail through the woods. Ziegler hadn’t shared her findings with any of them—except Heike, who she’d conscripted to chart their course a few weeks ago. Ever since then, Heike had been in a foul, vengeful mood. Lorelei could hazard a guess as to why.

Wilhelm had promised to marry someone from the province where the Ursprung was found, and Heike had made no secret of her aspirations: Wilhelm’s hand and the throne at his side. Clearly, the Ursprung was not in Sorvig.

A voice cut through the chilly silence: “I beg your pardon. Miss van der Kaas?”

A young man—one of Heike’s countless suitors, judging by his hopeful expression and the sweating glass of punch in his hand—sidled up to them.

“Ah, my drink!” She accepted the glass from him. “Thank you, Walter.”

“Werner,” he amended.

“Right.” Heike stared at him as though mystified he hadn’t already disappeared. “Did you still need something?”

He shifted on his feet. “You’d promised me your next dance.”

“Did I?” she said with mock surprise. “I’m afraid I’m dreadfully tired. Ah, but Miss Kaskel hasn’t danced all evening.”

“Nor do I intend to,” Lorelei said.

Predictably, the lordling recoiled. Try as she might to hide it, her accent exposed her for what she was. Fifty years ago, Yevani had stitched rings onto their cloaks with golden thread, but there was no point to it now. She was branded by her tongue as surely as she was by her government-issued surname.

“She’s just being demure.” Heike’s smile turned predatory. “Go on. Ask her.”

“If I do,” he managed, “people will talk.”

“Ask,” she repeated, all sweet pretense draining from her voice. “If you’re gallant enough, perhaps I’ll find a second wind.”

Now Lorelei understood what game Heike was playing. She’d almost feel a scrap of kinship—or at least pity—for the poor bastard if he weren’t eyeing her as though she were about to play some devilish trick on him. With grim resignation, he extended a hand to her. Lorelei could only stare at it in numb surprise.

Heike inspected her nails. “Is that all the grace you can muster?”

He met Lorelei’s eyes, his gaze smoldering with furious, humiliated resentment. “Miss Kaskel, would you do me the great honor of this dance?”

Indignation rose up within her. “I will not.”

Heike laughed. “All right, enough. You’ve convinced me. I will give you your dance, sir.”

Werner all but wilted in relief. As she tucked her hand into his elbow, Heike winked at Lorelei. “Good luck.”

She did not need luck. She needed another drink.

Just before the orchestra struck up a new song, a herald’s clarion voice cut through the chatter: “His Imperial Majesty King Wilhelm II.”

The crowd fell into a breathless hush. The doors of the balcony above the dance floor opened. King Wilhelm himself stepped into the wash of the chandeliers’ light. He was dressed, as he always was for his public appearances, in a scarlet military frock coat adorned with shining golden medals. Evidently, he’d earned every one of them. When he renewed his father’s war of unification at the beginning of his reign, he’d led his armies into battle himself, and it was said he’d had no less than three horses shot out from under him before he began taming dragonlings instead. He cut an impressive figure: tall and broad, with dark brown hair neatly combed back from his face.

No one dared move as he surveyed the crowd.

“Good evening, everyone.” A wide smile broke across his face. It was always a strange transformation, to watch a king become a man. “Thank you so much for coming tonight. Now, I know most of you are here for the food, but if you’ll indulge me, I want to talk about a dream. My father’s dream, really.”

Someone good-naturedly jeered in the audience, and Wilhelm’s smile turned almost bashful.

A dream was certainly one word for it. Wilhelm’s father, King Friedrich II, had set out to unite every Brunnisch-speaking territory under one banner: his own. Lorelei had to admire his ruthless efficiency. Before his death, Friedrich annexed nearly all of them in an ambitious military campaign, then executed anyone who refused to swear fealty to him. Once the streets ran red with the blood of traitors, he seized their lands and redistributed them to those he deemed more loyal—or at least more biddable.

At eighteen, Wilhelm had inherited both the crown and his father’s dream. By twenty, he’d seized the last free territories. Five years later, here he stood before them: the king of a tenuously united Brunnestaad.

“What unifying our kingdom has taught me is this: every Brunnestaader, no matter which province we hail from, no matter our class or creed, has a warrior’s spirit. We’re stubborn as hell. Few more so than my friends, which is more than half the reason I’ve chosen them to carry out this expedition. None of them needs introduction, of course, but for ceremony’s sake, I’d like to embarrass them.

“First, we have the lovely Heike van der Kaas, the expedition’s astronomer and navigator.” Wilhelm winked and extended a hand to her. “Join me up here, will you?”

Heike made a show of her ascent, tossing her hair over one bare shoulder and sliding her gloved fingers sensually along the banister. When at last she arrived at Wilhelm’s side, he took her hand and pressed a kiss to her knuckles. Bracing herself with one hand on his arm, she stood on her toes and whispered something in his ear. He smothered a laugh and all but shoved her away.

Once he recovered, he continued, “Adelheid de Mohl, our thaumatologist.”

Wilhelm spoke Adelheid’s name with a startling, wide-open yearning. It was foolish, Lorelei thought, for a man like him to display a weakness so plainly. Adelheid, for her part, met his gaze with cool indifference.

When she strode forward, the crowd shifted as if making way for a queen. She was a statuesque woman, not quite as tall as Lorelei but built along strong, decisive lines: broad shoulders, thick muscles, and sharp, cut-stone features. Her hair, the yellow of a bleak summer afternoon, was woven into a coronet around her temples. Adelheid was pragmatic in a way none of the others were, from her simple white gown to her plainspoken manner. Growing up in the province Ebul, where little but the hardiest things grew, toughened even a noblewoman. As soon as Adelheid reached the balcony, Heike looped her arm in Adelheid’s.

“Johann zu Wittelsbach, hero of the Battle of Neide and our medic.”

Johann skulked up the stairs, his shadow cutting harshly across the marble. Wilhelm clapped him on the shoulder and squeezed—whether fond or possessive or both, Lorelei could not tell. Johann did not move until the king released him.

Johann went to stand at Adelheid’s right-hand side. He rested one hand on the hilt of his saber as though ready to draw it at the first sign of danger. The two of them were nearly inseparable, with Johann trailing after Adelheid like her shadow.

“Ludwig von Meyer, our botanist.”

Ludwig emerged from the crowd dressed like a poisonous species: noxiously, clashingly bright. Or, perhaps more accurately, like a man with something to prove. After greeting the king with a handshake, he wedged himself beside Heike. He whispered something in her ear, and she pinched him in what seemed to be retaliation. Adelheid stared repressively at them both.

“And last but certainly not least, our naturalist, Sylvia von Wolff.” As she made her way toward the balcony, Wilhelm raised an eyebrow at her. “Who is joining us directly from the field, I see.”

The crowd tittered.

Lorelei recognized the irritated look on Sylvia’s face. Clearly, the rest of the group did, too. They looked on with matching expressions of dread. Sylvia, however, gathered her waterlogged skirts in both hands and curtsied to him. It seemed even she had the good sense to refrain from bickering with His Majesty in front of an audience.

When she rose, she strode past the others with her chin held high. Johann leered at her with a strange, predatory smile that made Lorelei’s skin crawl. Sylvia pointedly ignored him and stationed herself beside Ludwig. He nudged her shoulder encouragingly with his own.

An awed hush descended over the ballroom. Even Lorelei could not find it in herself to feel bitter. It was, admittedly, an arresting sight. All of them were as strange and luminous as distant stars. When Lorelei first arrived at the university, its glittering splendor was entirely foreign to her. But the most striking of everything on campus were the Ruhigburg Five.

They were one year older than her, drifting through campus as a single entity—like a hydra with warring heads—or else a group of heroes stepped right out of a myth. Rumors about them abounded, from the laughably mundane to the wildly improbable. That they’d all fought in the war together (true, save Ludwig and Heike); that Johann was the sole survivor of the Battle of Neide (questionable); that Adelheid had gotten no fewer than ten students expelled for cheating (plausible); that Sylvia had once, impromptu, taken the place of a lead soprano who’d injured herself minutes before curtain call (God willing, false).

Until last year, when Ziegler had brought Lorelei onto the team, she’d never imagined they’d deign to speak to her.

“Our people are many,” Wilhelm continued. “But no matter which province we hail from, whether we’re of noble or common blood, we’re bound together by an invisible thread. Our magic, our language, and most importantly, our stories. Who among us hasn’t grown up on the tale of the Ursprung?”

He paused for effect, and murmurs rippled through the ballroom.

“Let it be known that it is no longer just a story. We’ve found it.” His voice rose above the swelling noise of the crowd. “Claiming its power will establish Brunnestaad as a unified kingdom—and an unassailable one. Nothing shall tear us apart again, either inside or outside our borders.”

The air seemed to thicken with tension. Lorelei scanned the crowd. For as many gazing hungrily up at Wilhelm, others had clearly taken his words for the threat they were.

“Tonight is just the beginning.” His voice softened again. “But before we dance and make merry, I’d like to give the floor to the leader of the expedition and my personal walking encyclopedia, Professor Ingrid Ziegler.”

Her smile was tight as she climbed the stairs and took her place on the balcony. For the first time tonight, Lorelei truly saw her. Even though she knew, mathematically speaking, that Ziegler was forty-seven, she looked somehow ageless with her unlined face and overbright expression. Ziegler credited it to how much she walked. Lorelei had her doubts, although she could offer no other explanation. She was a stout, ruddy woman with graying chestnut hair and clear, blue eyes. She wore a gown in bold red satin, trimmed with ribbons and pearls. Although the Brunnisch court had caught on to the latest fashion trends, they were still woefully behind the rest of the continent. Standing above them, Ziegler looked like an exotic bird.

“Good evening,” she said. “I want to extend my deepest gratitude to King Wilhelm for being a patron of the arts and sciences over the course of his reign—and for generously relieving me of my courtly duties for this venture. It is my great honor to represent Ruhigburg University tonight. Now I want to introduce the co-leader of the expedition. She will serve as my right hand in the field.”

This was it: the moment Lorelei had been dreading for months. She didn’t know if she could bear to watch Sylvia basking in the light of their adoration. She couldn’t bear spending another night as her shadow, wallowing just outside her brilliance.

She couldn’t bear it.

“She is adept in the sciences,” Ziegler continued, “respected as a scholar, and she demonstrates an excellence of character and constitution, and a generosity of spirit and mind, that are requisite for this project. It is my great pleasure to introduce her to all of you.”

Sylvia seemed light as air, ready to take flight.

“Lorelei Kaskel,” Ziegler said, “will you please join me and say a few words?”

“What?” she and Sylvia said in unison.

It carried over the fragile hush in the room. Every eye was on her. Murmurs rippled through the crowd, but from somewhere outside herself, all she could hear was the same accusation echoing through her skull again and again.

Yevanisch viper.

Yevanisch thief.

Three

DARKNESS SETTLED HEAVY BETWEEN the walls of the Yevanverte.

Lorelei sat on the roof of her parents’ house, nursing a cup of coffee. Sleep eluded her so often, it had become something of a habit at this point: to keep watch as the moon poured its light over the single narrow street she called home. The coffee had dulled the sharpest edges of her headache—although it had done nothing at all for her fraying nerves. In no more than an hour, she would board a ship and leave this city for the first time in her life.

She had wanted this. That was the worst part about it. She had wanted this so desperately, yet she couldn’t find a shred of happiness.

Yevanisch viper.

She’d never regretted her reputation before. It made her life easier to encourage what they said about her. No one bothered her when they knew how sharp her tongue was. Few were openly hostile to her when there were rumors—false,regrettably—of how she had the power to tear a man’s blood from his veins. For so long, she’d believed her thorns would protect her. That if she spoke their language and rose in their ranks, she would be safe, maybe even accepted. How naïve she’d been.

Yevanisch thief.

With shaking hands, she took a gulp of coffee. It sat like venom on her tongue. Before she could think better of it, she dashed her mug on