7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Skelfs

- Sprache: Englisch

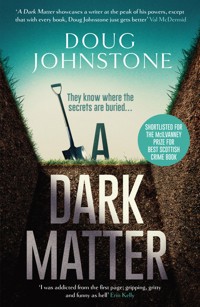

Three generations of women from the Skelfs family take over the family funeral home and PI businesses in the first book of a taut, gripping page-turning and darkly funny new series. ***Shortlisted for the McIlvanney Prize for Best Scottish Crime Book of the Year*** ***Shortlisted for the Amazon Publishing Capital Crime Awards*** 'An engrossing and beautifully written tale that bears all the Doug Johnstone hallmarks in its warmth and darkly comic undertones' Herald Scotland 'Gripping and blackly humorous' Observer 'I was addicted from the first page; gripping, gritty and darkly funny as hell' Erin Kelly 'A Dark Matter showcases a writer at the peak of his powers, except that with every book, Doug Johnstone just gets better' Val McDermid _________________ Meet the Skelfs: well-known Edinburgh family, proprietors of a long-established funeral-home business, and private investigators… When patriarch Jim dies, it's left to his wife Dorothy, daughter Jenny and granddaughter Hannah to take charge of both businesses, kicking off an unexpected series of events. Dorothy discovers mysterious payments to another woman, suggesting that Jim wasn't the husband she thought he was. Hannah's best friend Mel has vanished from university, and the simple adultery case that Jenny takes on leads to something stranger and far darker than any of them could have imagined. As the women struggle to come to terms with their grief, and the demands of the business threaten to overwhelm them, secrets from the past emerge, which change everything… A compelling, tense and shocking thriller and a darkly funny and warm portrait of a family in turmoil, A Dark Matter introduces a cast of unforgettable characters, marking the start of an addictive new series. _________________ 'A fiendish mystery that is also deeply moving and laced with suitably dark humour … set to be one of the books of the year' Mark Billingham 'Emotionally complex, richly layered and darkly funny. An addictive blend of Case Histories and Six Feet Under' Chris Brookmyre 'This dark but touching thriller makes for a thoroughly enjoyable slice of Edinburgh noir' Mary Paulson-Ellis 'This enjoyable mystery is also a touching and often funny portrayal of grief, as the three tough but tender main characters pick up the pieces and carry on: more, please' Guardian 'A tense ride … strong, believable characters' Kerry Hudson, Big Issue 'They are all wonderful characters: flawed, funny, brave — and well set up for a series. I wouldn't call him cosy, but there's warmth to Johnstone's writing' Sunday Times

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 462

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

iii

A DARK MATTER

DOUG JOHNSTONE

v

This one is for Chris Brookmyre, who has more faith in me than I have in myself.

vi

CONTENTS

1

JENNY

Her dad took much longer to burn than she expected.

Jenny watched the deep flames lick his body, curl around his chest and crotch, whisper in his ear. His thin hair crisped then turned to smoke, grey sinewy strands reaching into the mottled sky. A sprig of juniper in his hand caught alight and threw out blue sparks, and Jenny smelt the scent, reminding her of gin. The spruce and pine logs packed around Jim’s body were blazing bright and hard. The fire had destroyed his suit already and his skin was tightening around the bones as moisture evaporated from his body.

But still, it seemed to take a long time.

The funeral pyre wasn’t much more than a makeshift, oversized barbecue, two rows of concrete breezeblocks with a metal grill suspended between them. Underneath was a long silver tray borrowed from the embalming room, which they would use to gather his remains once the pieces were small enough to fall through the grate. Archie had been working on the pyre in the garden ever since Dorothy announced what her husband’s last wishes were.

It was contrary, Jenny had to admit. Her dad spent forty-five years orchestrating the funerals of thousands of people, arranging music and flowers, orders of service, funeral cars and sermons. Making sure every detail was right for the bereaved, ensuring all rival factions got what they wanted and the deceased was sent off in style. And yet his own funeral was the opposite. A pyre in their back garden, no speeches, no sermons, no friends or flowers or ceremony, just the five of them standing next to the throbbing heat of an illegal fire.2

Jenny looked away from the flames to the others standing around the fire. Her mum stood at the head of the pyre. A dancing mote of ash landed on her flowery yellow dress and she flicked at it with a bright fingernail. She brushed a strand of wavy grey hair from her forehead and lifted her face to the flames, eyes closed, like she was sunbathing.

Next to Dorothy, Hannah and Indy had their arms linked together, Hannah leaning her head on her girlfriend’s shoulder. They were so striking together, Hannah’s pale features and long, black hair the opposite of Indy’s brown skin and blue bob. Jenny wondered what was going through her daughter’s mind as her grandpa’s remains went up in smoke. It still seemed crazy to Jenny that she had a grown-up daughter in a relationship.

The flames were higher now, black smoke stretching into the air. The smell of pine and spruce made Jenny think of Christmas. Dorothy had placed bunches of herbs on the corpse before they began, and now bay and sage came to Jenny’s nose, mingling with the smell of burnt flesh to remind her of Sunday roast dinners.

She looked to the far end of the pyre, beyond Jim’s melting feet, and exchanged a look with Archie. He was busying himself with the logistics of the process, peering underneath, checking that the grate was holding up to the weight and temperatures, using a long pair of tongs to replace a fallen log by Jim’s shin. Jenny saw an iron poker and rake on the grass behind him, for sifting through the ashes once the flames had died.

Archie was short and thick, a heavy brown beard and shaved head, the way he moved suggesting something of a Tolkien character. He was the same age as Jenny but seemed older. He’d been Jim and Dorothy’s right-hand man for ten years, but it felt like he’d always been here. Archie was one of Dorothy’s strays, she had a habit of taking in lost souls, becoming an anchor in their lives. He had appeared one day to arrange his mother’s funeral. Over the next month he was often seen at cemeteries and cremations, crashing the funerals of strangers, trying to feel connected. At one 3in Craigmillar Castle Park, Dorothy approached him with a proposition, and within two weeks he was driving the hearse in a suit, changing into overalls to hammer together coffins, eventually taking over the embalming under Jim’s training. And Dorothy stuck by him when the details about his condition came to light. She sought a second opinion, kept an eye on his medication and therapy sessions, and trusted him around the place, which went a long way to saving his life.

The same went for Indy, another stray who pitched up three years ago to bury her Hindu parents, dentists killed in a car accident, leaving behind a rudderless daughter. But Dorothy saw something in her, and a month later she was answering phones, gathering information from clients and sorting admin. Now she was training to become a funeral director in her own right. Meanwhile she had slipped her way into Hannah’s heart and persuaded her to move into the flat she’d been left by her mum and dad, ten minutes’ walk away on Argyle Place.

Jenny stared at her dad as he charred and shrivelled, his essence mingling with the flames and smoke, dissipating into the universe. Part of her couldn’t believe she would never hear his dumb jokes again, that terrible vampire accent he put on sometimes to talk about death. The way he would wink at her, his little girl, during services, at the most inappropriate moments, making her cover her mouth and leave the room she’d sneaked into, because death was fascinating to kids.

But that fascination waned, being brought up around funerals began to take its toll. As a teenager she distanced herself, left home as soon as she could, studied journalism, worked, fell in love with Craig, had Hannah, divorced Craig, all the time staying away from death as much as possible.

But now death was back in her life.

She looked around. Tall oaks and pines lined the far wall of the garden, blocking the neighbours’ view. Over to her left was the open garage with the silver hearse parked inside, next to the workshop 4and embalming room. Those rooms adjoined the main house behind her, the large, three-storey Victorian sprawl that had been the Skelf family home for a hundred years. It had doubled as a funeral director’s for all that time, and a private investigator’s for the last decade, the businesses taking up the ground floor, the family living on the two floors above.

There was a rustle in the bushes to Jenny’s right and Schrödinger padded out from the foliage. The most recent of Dorothy’s strays, Schrödinger was a ginger tabby with the wiry body of a street cat and a supreme air of confidence. The name was Hannah’s idea and it stuck. As he got closer, Jenny saw something in his mouth. A bird, flashes of red, white and black on the face, yellow under the wing. A goldfinch.

Schrödinger never usually came near Jenny, she was a stranger round here, but he walked past the others and placed the finch at her feet. The cat glanced at the fire enveloping Jim’s body, sucking the energy from him, then wandered back into the bushes.

Jenny looked down at the goldfinch, blood smeared across the puncture wounds on its chest and throat.

Another dead body to dispose of.

She scooped it up in her hand and threw it onto the pyre, watching as its feathers burst into flames. She wiped the bird’s blood on her jeans and breathed deeply.

2

JENNY

Dorothy raised her glass. ‘To Jim.’

The three women clinked tumblers and sipped Highland Park. Jenny felt the burn as it went down. Any half-decent gin was her usual drink, but Dad loved whisky and this was for him. She placed her glass on the kitchen table and ran a finger over the grain of the oak, thought about the thousands of meals she’d eaten here as a kid.

Dorothy took a gulp of whisky and played with a clay dish in the middle of the table, something Hannah made at primary school with the yin and yang symbols on it. She made it for Dorothy, even back then interested in her gran’s worldview, the balance and connectedness of the world. The dish had a used-up tea-light in it, and Jenny thought of her dad in the garden, smouldering away as they sat here. She took another drink.

Archie was still down there tending the fire. When he’d begun using the poker on Jim’s body the three women had adjourned upstairs to the kitchen, Indy slipping off to look after reception. The same front desk dealt with both funeral and investigator businesses, different numbers to call but they came through to the same phone.

Jenny looked round the large open-plan kitchen. They were at the old table next to the functional kitchen stuff – cooker, fridge-freezer, cupboards – running along two walls. The adjacent wall was taken up by two large bay windows looking out over Bruntsfield Links. From here Jenny could see the crenellations of Edinburgh Castle ahead and the dome of Arthur’s Seat to the right. In between was the tree-lined park, a stream of students and 6school pupils crisscrossing from Bruntsfield to Marchmont and back the other way.

The final wall of the room had large whiteboards from waist to head height. One had ‘FD’ in thick letters across the top, the other ‘PI’. The kitchen doubled as the ops room, from which both businesses had been run for the last decade, since Jim surprised everyone by announcing he intended to expand out of the death industry into private investigations. Maybe it didn’t surprise everyone, Dorothy didn’t bat an eye, but Jenny struggled to get her head around it, and Jim evaded any questions from her.

The funeral whiteboard was the busier of the two at the moment. Four names were written in black marker under ‘FD’ – Gina O’Donnell, John Duggan, Arthur Ford and Ursula Bonetti – all in Dorothy’s neat hand. Beneath the names were various details for each. Where the body was to be picked up and whether it had been done yet, so one said RIE for the hospital at Little France, another read Marie Curie for the hospice in Frogston, the third was the city mortuary. The mortuary meant the police were involved and a post mortem had been done. Jenny was surprised that she remembered all this, despite never being involved in the business and not having lived here for twenty-five years.

Under each body’s pick-up information were the time, date and venue for the funeral, a spread of churches, cemeteries and crematoriums across the city. Warriston Crematorium for one, Morningside Cemetery for another. There were other shorthand acronyms for each service, how many cars were needed, who the celebrant was, what type of service. On the wall next to the whiteboard was a large map of Edinburgh covered in different coloured pins. A map of the dead of the city. Jenny imagined the pattern that would emerge if you joined all the dots together.

In comparison the PI board was pretty empty. It was less regimented too, a bit like those boards in police dramas but without the pictures of mutilated women with red lines to serial killers or terrorist suspects. Instead there was a name at the top, Jacob 7Glassman, with another name, Susan Raymond, written underneath. Then some scribbles in Jim’s handwriting that Jenny couldn’t decipher. She stared at the writing, a thread connecting her dad to a world that was trundling on without him. Outside the window, school kids were kicking a football around, an old woman walked her sausage dog, two cyclists in Lycra zipped along the path to the Meadows, none of them aware of the man crumbling to ashes in the garden downstairs. The only dad she would ever have.

‘I can’t believe Grandpa’s dead,’ Hannah said. She held her tumbler to her chest. Not much of a drinker, something Jenny was happy about. Such a different attitude to alcohol now in Scotland. As a teenager, Jenny was sneaking half-bottles out onto the Links to drink with her mates, Dorothy and Jim oblivious. It had left her with a legacy of drink in her veins. Not a problem, she wouldn’t call it that, but alcohol was background radiation in her life, a trace of it in everything.

She finished her Highland Park and poured another for her and Dorothy.

‘I know,’ she said.

Dorothy breathed in through her nose and out through her mouth, a considered movement from decades of yoga.

‘He had a good life,’ she said, a hint of her Californian accent still there after all these years.

‘I’m not ready for him to go,’ Jenny said.

Dorothy leaned back and her chair creaked. ‘There’s nothing we can do.’

Jenny shook her head and sipped her whisky.

‘What was that all about, anyway?’ she said, angling her glass towards the door.

‘What?’ Dorothy said.

‘The human barbecue downstairs.’

Dorothy shrugged. ‘It’s what he wanted. He was sick of the formal stuff, the ceremony of it.’8

Hannah frowned. ‘But he always said people needed the rules and structure to give them closure.’

‘Maybe he thought we didn’t need that,’ Dorothy said.

Jenny wanted to kick her chair back and scream out of the window, lift her tumbler and smash it against the funeral board, splatter whisky over those other deaths. She sat still.

‘But it was illegal,’ she said. She knew enough about the funeral business to know that burning a body in your back garden was not OK.

‘No one will know,’ Dorothy said. ‘Or care.’

‘You think?’ Jenny said. She hated how she sounded, like the bratty teenager she once was, sitting at this same table, moaning that Dorothy and Jim wouldn’t let her go to some all-night rave at Ingliston with two thirty-year-old men she barely knew. Here she was, a forty-five-year-old divorcee with a grown-up daughter, and she still felt like a brat. Maybe it was Dad’s funeral bringing it all to the surface, or maybe it was simply being back in this house of death.

‘I know this is hard on you,’ Dorothy said. ‘Both of you.’

Jenny felt ashamed. This was Dorothy’s husband of fifty years she was saying goodbye to, they had all lost a massive part of their lives. It wasn’t a competition.

‘And for you, Mum,’ she said, reaching her hand across the table.

Dorothy chewed the inside of her cheek and took Jenny’s hand. Her skin was still soft at the age of seventy. She seemed much younger than that, and always had a look on her face, even now, suggesting she was at peace with the world.

Hannah put her hand on top of Jenny’s and Dorothy’s, which made it feel like they were a gang about to execute a heist. They each pulled away just as the doorbell rang downstairs.

Dorothy sighed and pushed back her chair, but Hannah put a hand out to stop her.

‘Indy can handle it,’ she said. ‘You know that.’

Dorothy hesitated then nodded.

Hannah was so in love it made Jenny’s heart swell. Jenny had 9only felt the overwhelming power of love like that once before, with Craig. And, well.

She heard muffled conversation downstairs, then steady footsteps and a tap on the open kitchen door.

‘Dad, you came.’ Hannah jumped up with a scrape of her chair and ran over to Craig standing in the doorway. He held a bunch of red lilies and had a demure expression. Hannah put her arms around him and squeezed, and he hugged her back.

‘Hi, Angel,’ he said.

Hannah released him and he looked towards the table and nodded. ‘Jen.’

‘Craig.’

He walked into the room, offering the lilies. ‘These are for you, Dorothy, I’m sorry about Jim. Hannah told me and I wanted to pay my respects. He was a good man.’

He glanced at Jenny and she rolled her eyes. Damn it, he still looked good. He never seemed to thicken around the middle like most guys his age, and the flecks of grey through his hair made him look better somehow. Maybe being a dad again to little Sophia was keeping him young, or maybe it was the sex with Fiona, the blonde dynamo who was now the second Mrs McNamara. That was the most annoying thing, that he’d cheated on Jenny with someone the same age, a diminutive Reese Witherspoon type, go-getting and ambitious.

Enough. She resisted the urge to say something sarcastic. It was ten years ago and he’d always been a good dad to Hannah. None of which made it easier.

‘They’re beautiful,’ Dorothy said, accepting the flowers and a kiss on the cheek. She fetched a vase from a cupboard. ‘Stay for a drink.’

Craig looked at Jenny. ‘I don’t want to impose.’

Dorothy poured water into the vase and arranged the lilies. Jenny could smell the flowers, powerful and musky. Lilies always struck her as masculine.10

‘Stay, Dad,’ Hannah said.

Craig looked at Jenny with his eyebrows raised, waiting for her to say OK.

She swept a magnanimous hand across the table. ‘Sit.’

When he first told Jenny he was having an affair and leaving her, it almost killed her trying to stay civil in front of Hannah. But she was damned if she was going to let hate and bitterness eat her up, and she didn’t want all that toxic shit infecting her daughter. As the years went by it became easier, much to Jenny’s surprise. You could get used to anything, it seemed. But she still had to bite her tongue, stop herself becoming the vicious harpy, the wronged woman. Of course, that let him off the hook.

Dorothy put the lilies on the table then got a whisky tumbler from the cupboard and poured Craig a drink.

‘So when’s the funeral?’ Craig said, sipping.

Hannah frowned. ‘We just did it.’

‘When?’

‘Now, in the back garden.’

Craig look confused. ‘Wait, that’s the smoke over the house?’

Hannah nodded. ‘Just us, no service.’

‘Are you allowed to cremate folk here?’

Hannah shook her head as Dorothy sat down and refilled her glass.

Jenny’s phone vibrated in her pocket and she pulled it out. Kenny from The Standard. He never called. Always email, a quick back and forth about her column, then copy submitted on deadline.

She stood up and walked towards the door. ‘I need to take this.’

She pressed reply in the hallway. ‘Kenny.’

‘Hi, Jenny.’ His tone of voice was not good.

‘Copy’s not due for a couple of days.’

She walked to her childhood bedroom, now redecorated as a minimalist guest room, pine bed, stripped floorboards, narrow shelf holding the overspill from Dorothy’s book collection.11

She heard a sigh down the line. ‘There’s no easy way to say this, we’re cancelling your column.’

‘What?’

‘You know what it’s like here, Marie Celeste meets the Titanic. The numbers don’t add up.’

She wasn’t surprised but she wasn’t prepared either. Everyone she knew who’d started as a journalist at the same time as her had wangled an exit strategy, gone into PR like Craig, or teaching or consulting, or even politics. A career in journalism was death by a thousand cuts, and here was the final knife in her guts.

‘When?’

‘Immediately.’

‘Kenny, I need this, it’s the only regular gig I have left, you know that.’

She fingered a book on the shelf, pulled it out. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. She remembered seeing it around the house growing up, a flower blooming from a spanner on the front cover. She’d never read it.

‘I’m sorry,’ Kenny said.

‘I can’t pay the rent as it is.’

‘Not that it’s any consolation, but I’m getting the bullet soon as well.’

‘You’re right,’ Jenny said. ‘That’s no consolation.’

She walked to the window and looked out at the back garden. Archie was tending the pyre, which had reduced to a low pile of smouldering remains. Black and white and grey, ash and bone, Archie raking round the edges, dust sifting onto the body tray below. Jenny saw charred blobs where Dad’s shoes had been and wondered about his feet. Size eleven and thin, the second toe longer than the big one, something she and Hannah both inherited.

‘We’re slashing across the paper,’ Kenny said.

‘Freelancers first.’

‘You know how it is.’12

No contracts, easy to terminate at zero cost. Just shift the work of filling pages in-house, make the subs who are left write the columns and reviews and everything else, and if they don’t like it some bright wee sod from journalism school will do it for nothing to get their name in the paper.

Out of the window Jenny saw Schrödinger stalking along the hedge line, his eye on a woodpigeon roosting in a bush. He leapt for it, but the bird fluttered to the top of the hedge and looked down at him. Schrödinger was nonplussed, life was all a game.

‘Let me know if there’s anything I can do,’ Kenny said.

‘OK.’

‘I have to go. Stay in touch, yeah?’

Jenny ended the call. She was still holding that book, the flower and the spanner, one transforming into the other as if it was that easy to change your life. Maybe if she read the book she could come up with another way to live, another way to see the world.

She returned the book to the shelf and went back to the kitchen. The three of them were sitting around the table sighing like people do after someone says something funny but poignant. Jenny always seemed to miss the joke. They lifted their drinks in unison as if hearing a telepathic message that Jenny was deaf to.

Craig looked at Dorothy.

‘But what about the businesses?’ he said, as if continuing a conversation.

Dorothy smiled. ‘I have Archie and Indy.’

‘Indy’s training to become a funeral director,’ Hannah said, beaming with pride.

‘That’s great,’ Craig said. He lifted his glass and pointed at the two whiteboards on the wall. ‘But there’s a lot to do. Jim was…’ Maybe he didn’t want to remind the women of their loss.

Dorothy nodded, acknowledging Craig’s diplomacy, then gazed into her glass, swilled the Highland Park, watched as it clung to the sides then slipped down.

Jenny knew what was coming, she’d expected it since she got 13the news about Dad. She was surprised it hadn’t been mentioned earlier, but here it was, she was ready.

Dorothy took a sip, stared at her glass. ‘I thought maybe Jenny could help out. Stay for a bit, keep me company.’ Now she looked up. ‘Just for a while.’

Jenny thought about the phone call, her overdue rent, that stupid book with the flower on it. She could smell lily pollen and whisky and she thought about never seeing her dad again.

‘Sure.’

3

HANNAH

Hannah took Indy’s hand as they walked through the front garden. She glanced back at the first-floor window knowing Gran would be there. She smiled and waved then turned away. It felt weird leaving her alone, but Mum was just nipping to her flat across town in Portobello to pick up a few things and coming straight back. It was good they’d be spending time together, they needed each other right now. Everyone needs someone. She leaned over and kissed Indy on the cheek.

‘What’s that for?’

‘Can’t I kiss my girlfriend’s beautiful face?’

Indy mimed being sick, fingers down her throat.

‘Piss off,’ Hannah laughed.

They went past the gateposts at the end of the drive and Hannah smiled at the address carved into the stonework, 0 Greenhill Gardens. Number zero, just one of the things that marked this place as special. She asked Dorothy and Jenny about it when she was younger, but Gran just shook her head as if it was a cosmic joke, and Jenny shrugged like it never occurred to her that it was odd. Hannah did some research and it turned out their house was added to the street later than others, by an eccentric brewery owner in the late 1800s. In those days you could make up your own address, but instead of creating a new street name Mr Bartholomew plumped for number zero on the street already there, right next to the existing number one. Posties had been confused ever since.

Something about it appealed to Hannah’s mind. Zero was hard to define mathematically and asking about it led into philosophical 15territory, which she loved. She was studying metaphysics as an optional course, and sometimes popped into lectures on category theory, the maths of maths, to get her brain fried. That abstract space, the way matrices, theories and equations interlinked, the way they mapped out a universe you could superimpose on the real world, she was into it.

‘What are you smiling about?’ Indy said.

They were round the corner and into the park. The web of paths was full of students and workies heading home after lectures and the office. Hannah loved that everyone lived cheek by jowl here, she felt part of something.

‘Just happy to be alive,’ she said.

‘Oh my God.’

‘Which one?’

A running joke, Indy a lapsed Hindu.

The truth was Hannah really was happy to be alive, despite just watching her grandpa being cremated. Maybe because of that. Dorothy once told her that some people got horny at funerals, determined to get on with the business of living in the face of death. Hannah could relate.

They crossed Whitehouse Loan onto the north part of Bruntsfield Links where the pitch and putt was. The undulations of the ground always made Hannah think of the ancient burial site under the surface. She wondered how many of the kids and parents knocking golf balls around realised there were hundreds of seventeenth-century plague victims buried below. Another layer of existence beneath reality.

They cut round the top of the Links to Marchmont then onto Melville Drive. The sun was still high this early in autumn, and the light through the chestnut trees strobed across her eyes. She looked at Indy’s face as it dappled between light and shade. In fourth year at school Hannah briefly dated an epileptic boy who had to cross the road when low sunlight flickered through railings. She wondered about that loss of control, reactions in the brain 16making you who you are. Depression, anxiety, love, hate, anger. She thought about neurons firing, particles shifting state, quarks changing their distributions.

She caught the smell of charcoal and burgers from barbecues across the road. The Meadows were full of students exploiting the last warm days before the country shut down for winter. Frisbees, football, in the distance some girls playing quidditch. Harry Potter was before her time, she preferred The Hunger Games, stronger women for a start. But you couldn’t exactly play Hunger Games in the park.

They reached the flat and bounded up to the top floor. Indy opened the door and they fell inside. Hannah worried that she was supposed to feel down because of Grandpa, but she felt full of possibility. Jim wouldn’t want her to mope around, even though she missed him. And maybe Dorothy was right, maybe death makes you horny.

She grabbed Indy’s waist and spun her round, kissed her, stared at those brown eyes. ‘Love you, babes.’

Indy looked at her sideways. ‘What’s got into you?’

Hannah kissed her again, long and deep, eased her against the wall.

Indy pulled back. ‘Just a minute.’ She called out. ‘Mel?’

They waited for a reply.

‘She must still be at King’s Buildings,’ Hannah said. Though she knew lectures were over for the day, and it wasn’t like Mel to head to the pub afterwards, like some of their classmates. Hannah had skipped lectures on special relativity and quantum field theory this afternoon, Mel saying she would let her know if she missed anything.

Hannah went to kiss Indy again and Indy responded, then a phone rang. It came from Mel’s room.

‘Leave it,’ Indy said, her hand on Hannah’s back.

Hannah frowned. Classes were over. Mel was super-reliable and organised, and never went anywhere without her phone.

Hannah unpeeled herself from Indy and went to Mel’s door, 17knocked twice. Waited. The phone kept ringing. She pushed the door open. Everything seemed normal, the single bed made, the desk neat with piles of notes and textbooks, Mel’s photo montage on the wall, pictures of her with friends and family.

The phone was on the desk, still ringing.

‘Mum’ flashed on the screen.

Hannah felt Indy at the doorway behind her as she picked up the phone and answered.

‘Hi, Mrs C, Hannah here.’

‘I told you before, call me Yu. What have you done with my daughter?’ Her voice was bubbly, strong Canton accent, but there was an edge.

‘I don’t know, me and Indy were out all day and just got in. I found her phone in her room.’

‘I’ll kill her,’ Yu said, in a tone that meant she would do the opposite. ‘She was supposed to meet her father and me for lunch. It’s my birthday.’

‘Happy Birthday.’

‘Thanks, dear, but I wanted to spend it with my daughter.’

Melanie never missed appointments and she would never, ever miss her mum’s birthday.

‘I’m sorry,’ Hannah said, trying to keep her voice light. ‘When I see Mel, I’ll tell her she’s in trouble.’

‘You have no idea where she might be?’

Hannah looked out of Mel’s window. Her room faced onto Argyle Place, but you could still see a swathe of the Meadows, a sliver of Salisbury Crags in the distance. ‘We had classes this afternoon. I wasn’t there, it was my grandpa’s funeral.’

‘Oh, baby, I’m sorry.’

‘It’s OK. But I know Mel was going to lectures. She probably just got caught up with something at uni.’

That was no excuse at all. The classes were in the afternoon, nothing to do with lunch, but Hannah couldn’t think what else to say.18

‘OK, dear,’ Yu said. There was hesitation down the line. ‘You get her to call me as soon as she gets home, understand?’

‘I will,’ Hannah said. ‘Bye.’

She hung up and turned to Indy, raised her eyebrows.

Indy stepped into the room. ‘I heard.’

She walked to where Hannah was standing, staring at the home screen of Mel’s phone, a picture of her with Xander from their year, the two of them dressed up for a Valentine’s Day dinner. Hannah remembered helping Mel decide what to wear that night.

‘Something’s wrong,’ Hannah said.

4

DOROTHY

Dorothy stood in the embalming room and stared at what was left of Jim. An outdoor funeral pyre doesn’t reach the temperature of a cremation oven, a couple of hundred degrees lower, so his remains were chunkier than they usually got back from crematoriums. Also, crems sift the remaining bone fragments and pulverise them in a cremulator, so the bereaved get a nice pile of grey sand for scattering.

In comparison, the bone fragments and dust in front of her were real. And it was dust, not ashes, that was a misnomer. She was thankful that the fire hadn’t left any large bones for her to deal with, nothing longer than a few inches amongst the dirt. She imagined lifting an intact skull from the pile, addressing it like Hamlet. Or one of Jim’s femurs, waving it around like a cavewoman.

She looked up from the table. It was too bright for this, but it was a workplace after all, Archie needed plenty of light. Apart from Jim on the table, the place was spotless, Archie always made sure of that. The six body-fridges along one wall hummed, the names and details of the dead inside written on magnetic cards stuck to the front of each fridge. Arthur Ford, five foot eleven, viewing required, embalming needed, no jewellery, removed from the Western General. It tied in with the whiteboard upstairs, and for a moment Dorothy had a flash of the business as a single giant organism.

She turned back to Jim’s remains. Picked up a four-inch shard of white bone. It was as light as balsa wood but solid, all the organic content and moisture vaporised. She held it up to the 20light, turned it in her fingers. It had one straight edge and one gently curved, and was wider at one end than the other with a round indentation at the wide end, like it might’ve been a socket for a ball joint. The narrow end was sharp, and she pushed her thumb against it, felt the pain. She kept pushing until it broke the skin, watched as a droplet of her blood spread along the tip of the bone, darkening it. She sucked her thumb and put the bone in the pocket of her cardigan.

She thought of all the atoms from Jim’s body now floating in the sky across Edinburgh, rising into the upper reaches of the atmosphere. She thought of other atoms from his pyre dropping onto the soil in their garden, their neighbours’ gardens. She thought of the atoms in the brush Archie used to tidy up, the atoms stuck in her own hair, on her clothes, her shoes, in her nose and ears and throat. She licked her pinkie finger and dipped it in the dust on the tray, then sucked it.

He tasted of bonfires and dirt. All that was left of fifty years together. She breathed deeply and looked at the embalming table alongside, bottles of chemicals and pumps lined up on the far workstation, razors, scissors, creams and sprays, the collapsible gurney they brought the bodies in on. Collecting bodies was a two-person job, Jim and Archie for years. Now someone else would have to step in, maybe her. She’d done the funeral arranging together with Jim for years but she hadn’t got as involved with the body side of the business. She was good at logistics, good with people, had worked for the company part-time on and off her whole life, while raising Jenny at the same time. Indy could step up, she was training to be a funeral director anyway, she was small but strong, tough in a way none of the Skelfs were. Dorothy saw it in her the moment they met, same with Archie. All part of their extended surrogate family. A family that had now lost its heart.

She left the room, switching the light out on her husband, the ashen taste of him still on her tongue, his sharp bone with her blood on it nestled in her pocket.21

She sat at the desk in the small office and frowned, paperwork scattered in front of her. She took a sip of whisky and sucked her teeth. She’d been drinking too much all week, since she found Jim on the bathroom floor, eyes open, pyjama trousers at his ankles.

She picked up the bank statement again, adjusted her glasses, and compared it to another piece of paper. She needed more light in here, or better glasses. She thought about Jim’s eyeballs, evaporated into nothing. She looked at an open book of accounts and squinted as she ran her finger down the page. Something didn’t add up.

Jim always handled the business side of things, Dorothy was hopeless with numbers. Hannah got her love of maths from him. Maybe Dorothy was misunderstanding it, but there seemed to be money missing. Not a big lump sum gone wandering, but a steady amount leaving the business account for months. No, years. Into a sort code and account number she didn’t recognise, with no reference name. She shuffled papers, looked again, took another hit of Highland Park. The whisky wasn’t helping.

She sighed. Maybe she was overlooking something simple, something that would explain the five hundred pounds coming out of their account every month for years. She must know about this, Jim would’ve told her. Because if he didn’t tell her, that meant it was a secret, and she couldn’t cope with that. She needed to speak to someone but the person she always spoke to when something was wrong was Jim.

She searched amongst the papers on the table and found her old Nokia, thumbed through the handful of contacts and stopped at Thomas. She looked at his name for a few seconds then called, pushing her glasses onto the top of her head. She drank whisky and sat back in her chair, then pinched the bridge of her nose and listened to the ringing.22

‘Hello?’

‘Hi, Thomas, it’s Dorothy.’

‘It’s a little late.’ He sounded sleepy. ‘Are you OK?’

She glanced at the clock on the wall, 1 a.m. ‘Did I wake you?’

‘What’s up?’

They’d been friends for five years, since he came to her yoga class. He’d attracted everyone’s attention, any man at a yoga class gets attention, especially a tall black man with an accent drifting between Scotland and Sweden. When the women discovered he was a police officer it was too much. Dorothy liked him straight away, he was softer than the Scottish men she knew, despite being a cop. Two months after that first class she bumped into him on Chambers Street and they went for coffee. It felt good to be talking with a man who wasn’t her husband. Nothing more than that.

Then two years ago Thomas’s wife Morag died suddenly. A heart attack while riding her bike through Southside traffic, she hit the kerb and bounced into a parked van. The Skelfs did the funeral. Wasn’t too much of a reconstruction job, would’ve been much worse if she’d fallen into an oncoming vehicle. Thomas and Morag didn’t have kids and all his family were in Sweden, so Dorothy helped out and they became close. Jim knew they met for coffee and maybe he thought it was strange but he never said anything.

Thomas’s grief gradually subsided, a scenario Dorothy had seen a hundred times before. She wondered about her own grief. It was so individual for each person, she knew that well from the business. After the initial shock of finding Jim she’d wallowed for days. Arranging the pyre had focused her, but it also made her kind of numb. Again, she’d seen that so often with clients. She wondered when the waves would hit, how bad they would be, how deep she would go. But she would survive, everyone did, and the pain would reduce with time. That was almost as unbearable, the knowledge that the grief, along with her memories of Jim, would fade.

‘Jim’s dead,’ she said.23

‘Oh, Dorothy.’

She rubbed at her forehead. ‘Heart attack.’

The words hung between them, giving them a link to each other, both their partners killed the same way.

‘I’m so sorry,’ Thomas said.

‘It happened a week ago,’ Dorothy said, swirling the whisky in her glass. ‘During the night, while he was on the toilet. I found him in the morning. Where’s the dignity in that?’

She hadn’t told anyone the details of how she found him. She’d removed his piss-stained pyjama trousers and put them in the wash basket. Grabbed a new pair from the chest of drawers and pulled them up his legs, then dragged him into the bedroom and heaved him onto the bed. He’d been dead for hours, skin cold, a feeling she was used to in this business. She lay down and held him for half an hour, tried to clear her mind. She didn’t phone a doctor for another hour, because once she did that, Jim wasn’t hers anymore, his death was everyone’s. She wanted to keep it to herself as long as she could.

‘A week ago?’ Thomas said.

There was a slight reprimand in his tone. Why hadn’t she told him sooner? He could’ve helped.

But how could he?

‘We cremated him today.’

‘If you’d told me, I would’ve come.’

‘We didn’t tell anyone.’

She heard him shift his weight and wondered if he still used the same side of the bed as when Morag was alive. She hadn’t spread herself out in the last week, to use Jim’s side of the bed seemed an insult to him.

‘If there’s anything I can do,’ Thomas said.

Dorothy lowered her glasses to her eyes and stared at the paperwork on the desk.

‘There is a way you can help,’ she said, lifting a bank statement. ‘I want you to look into something for me.’

5

HANNAH

Hannah was properly worried. She stood in Mel’s room feeling like an intruder. It was dark outside now, the sodium lights from the street making the room feel seedy. She ran a finger along a bookshelf, opened a drawer of the desk and found stationery, not much else.

She’d checked all Mel’s social media, once earlier this evening, then again twenty minutes ago. No activity. She’d called round all their friends and no one had seen Mel today. As far as Hannah could work out, she was the last one to speak to Mel, at breakfast. There was a full day of classes, fluid dynamics labs in the morning, two lectures and a tutorial in the afternoon, and Mel wasn’t at any of them. And she had specifically said she would take notes for Hannah.

Hannah had called Xander first, who said he hadn’t seen her since lunchtime yesterday. He was an astrophysicist, a subject even more complex than the stuff Hannah and Mel were studying. She tried to think what she knew about him. He was in the Quantum Club with Hannah, Mel and a few others, and his parents had something to do with the military and lived abroad.

She called a few other names in Mel’s phone, but no one had heard from her. That included her brother Vic who worked at the Fruitmarket Gallery in town. He was close to his sister and said he’d spoken to her yesterday, just small talk about her meeting their folks for lunch. He was shocked when he learned Mel hadn’t turned up.

Hannah posted on the third-year physics undergrad message board, asked if anyone had seen her, tried to keep it low key. She 25checked Mel’s WhatsApp and text messages, nothing that would raise an eyebrow.

She went over this morning’s breakfast in her mind. She hadn’t exactly been focused, thinking about Jim’s cremation. Had Mel seemed a bit off, a little nervous or anxious? Maybe Hannah was superimposing her current frame of mind onto her memories.

She looked at the time on Mel’s phone, almost 2 a.m.

Indy was behind her now in the room. ‘What are you thinking?’

Hannah shook her head, pulled out her own phone and dialled 101. She shared a look with Indy as she waited for them to pick up.

‘Hello,’ she said. ‘I’d like to report a missing person.’

6

JENNY

Jenny felt the edges of the single mattress under her with her hands and was confused for a moment, then she remembered and opened her eyes. She was glad the room had been redecorated since her childhood, it gave her a little distance. It would’ve been too much to be back here as a middle-aged woman in the same bed she lay in as a teenager, thinking of Kurt Cobain and touching herself.

But there were still one or two reminders. The creaky floorboard next to the bed had never been fixed, and the noise it made as she stood up was overpoweringly nostalgic, sending her hurtling back through the decades to when she was a child. On the wall next to the door she could see the dent in the plaster where she’d punched it several times, furious that Susan Wilson was going out with Andy Shepherd, even though Susan knew Jenny liked him. And in the bottom corner of the window her initials were still scraped into the glass, as clear as if they were tattooed on her chest.

Being back here, Christ. Mum needed her but Jenny wasn’t kidding herself this was temporary. At forty-five years old Jenny had nowhere to live, no assets, no job, no marriage. She might as well be here, where better to end your days than in a funeral home?

She looked at the open suitcase on the floor, her clothes spilling out in a mess. The rest of her belongings were in a handful of boxes in the storeroom downstairs. Archie had helped her do a moonlight flit from the Portobello flat last night. Packing up all her stuff had taken a depressingly short time, and she left the crappy furniture as part payment for her rent arrears.27

She couldn’t fathom how it had come to this. Twenty years ago, when they started renting that place on Bellfield Street, she was married, pregnant and in love. She and Craig were skint, both freelance journos, her doing cultural commentary, him covering politics. There was no chance of getting on the housing ladder with no steady income, but they’d presumed things would look up. Instead the journalism industry collapsed, Craig left her, only then starting to make money in PR with the business he set up with Fiona.

Dorothy and Jim had offered to take Jenny and Hannah in. Jim especially was incensed at Craig leaving, furious at the idea of any man betraying his family. He, more than Dorothy, tried to cajole Jenny and Hannah back into the fold, long play sessions and ice creams with his granddaughter, late-night phone conversations with Jenny, pleading with her to come home. But something about that rankled her. The idea she couldn’t provide for her daughter. Which was stupid pride, looking back. Plus she didn’t want Hannah growing up around dead bodies, the way she had. So she redoubled her freelancing efforts, busted herself trying to pay rent, perhaps at the expense of her relationship with Hannah. Maybe it was the wrong decision, one of the millions of wrong life decisions that had brought her back to the Skelf house.

She imagined the thousands of bodies that had passed through this place, pictured them rising from graveyards across the city, hordes of zombies marching towards Greenhill Gardens to reclaim their links to the living. Maybe she was doing that too, trying to get her father back, reconnect with Mum.

She pulled on a dressing gown from her open suitcase and padded through to the kitchen. Schrödinger was perched on a battered leather chair by one of the windows, face turned to the sun glinting through the trees. He didn’t acknowledge her. Jenny grabbed a mug, poured some coffee and water into Dorothy’s large stovetop pot. She could only ever be bothered with instant at home so this Columbian roast would blow her head off.28

She walked to the window.

‘Hey, cat.’

Nothing. She stroked the nape of his neck. ‘Look, we need to get along, I’m going to be here for a while.’

Schrödinger stretched away to the other side of the chair, his claws digging into the leather.

‘Fuck you,’ Jenny said.

‘Who are you swearing at?’ Dorothy came through the door looking surprisingly fresh-faced.

‘Your cat,’ she said. ‘He hates me.’

‘He responds well to being sworn at, just like humans.’

Jenny smiled and returned to the stove, started making coffee. ‘Want one?’

Dorothy shook her head. ‘I’m going out, meeting a friend.’

‘Who?’

Dorothy stopped. She was wearing loose cotton trousers and a maroon silk blouse, open at the neck. They both suited her, she always knew how to dress well. Jenny was envious, her elegant mother gliding through life. Her calm air gave the impression that nothing fazed her. Jenny couldn’t understand why she didn’t seem more upset about her dad.

Dorothy put her hands on her hips. ‘Thomas Olsson.’

Jenny had heard his name mentioned before but never met him, a Swedish cop friend of Dorothy’s. The Skelfs had buried his wife, and Indy said he was a bit of a silver fox.

‘You’re off to meet a handsome widower the day after cremating your husband?’

Dorothy raised her eyebrows at Jenny’s tone. ‘I can do whatever I want.’

‘Just like you did in eighty-seven.’

Dorothy froze. Eighty-seven was shorthand for what came to be regarded within the family as ‘Dorothy’s episode’. A solo trip to visit her mum in Pismo Beach, supposedly for two weeks, turned into almost two months. Jim and a hormonal Jenny were 29left in Scotland wondering what the hell was going on. Turned out Dorothy was hooking up with an old school flame, recently divorced, the pair of them trying to grab on to their disappearing youth one last time. In the end, Jim had to fly to California to talk Dorothy into coming back. Jenny never really understood how, but her mum and dad managed to put it behind them. Jim forgave Dorothy and she was clearly full of remorse, but Jenny never properly got over it. A germ of an idea about the possibility of betrayal and deceit sprouted in her mind, then years later, when Hannah was almost the same age as she had been, Craig went and did the same thing, only much worse. That reopened the wound, made it hard to accept her mum’s comfort and support through her own separation and divorce. And now this, Jim’s burnt remains downstairs on a slab, and Dorothy dressed nice and heading out to meet an eligible widower.

‘Don’t you dare,’ Dorothy said. ‘You have no right to bring that up.’

‘Whatever you say.’

‘Your dad was the love of my life. What happened back then was a mistake, one I’ve always regretted. And to bring it up now, my God.’

Jenny held out her hands. ‘OK.’

‘I don’t need permission to live.’

‘Fine.’

The coffee pot burbled on the stove as Schrödinger wandered over to Dorothy and ran his tail round her legs. She stroked him and pointed at the doorway.

‘I need you to cover the front desk for a while,’ she said. ‘It’s Indy’s day off.’

Jenny felt a bubble of anxiety rise inside her as she poured the coffee. ‘I don’t know what to do.’

‘Just answer the phone if it rings and take down details. You’ve seen me do it often enough.’

‘Not recently.’30

‘You’ll be fine.’ Dorothy lifted her cardigan from the back of a chair and put it on. Jenny smelt the smoke on it from yesterday, imagined her dad’s spirit in the wool.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘Are you OK?’

‘No,’ Dorothy said, not unkindly. ‘Neither of us is OK, and I don’t expect we will be for a long time. But we need to carry on, don’t we?’

‘Do we?’

Dorothy took Jenny’s hand. ‘What else can we do?’

The phone rang.

Jenny was in the embalming room staring at the pile of dust that was her dad when she heard the ringing from reception. She wasn’t sure how long she’d been standing there, could’ve been seconds or weeks.

She walked through to reception. Such a contrast to the embalming room, here were plush carpets, carved oak fixtures, bouquets of flowers in a corner waiting for the next service. Egg and dart cornicing around the ceiling, a stylish desk with a laptop and telephone. From reception she could see the whole customer side of the business on the ground floor – the small chapel to the left, the arranging room to the right, and the three viewing rooms along the back.

She sat in the chair and stared at the phone, then picked it up.

‘Hello, Skelf’s?’ She remembered not to say funeral director or private investigator, because it could be either.

Sniffling down the line.

‘It’s OK, take your time.’ Jenny pictured her mum saying the same thing thousands of times over the years.

‘It’s my William.’

Jenny heard her mum’s voice in her head. Just be there, you don’t 31have to say anything. People want to feel connected to someone, to anything.

More sniffing. ‘I need to arrange his funeral.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that.’

The woman burst out crying and Jenny felt helpless. If they’d been in the same room she could’ve offered a tissue or patted her hand. Or given her a bear hug like she needed herself, maybe share some tears, break out the single malt and drown their sorrows together. How fucked up was it to be sitting the day after your dad’s funeral listening to the worst moment of someone else’s life?

‘What’s your name?’ Jenny said.

A while before she answered. ‘Mary. William and Mary Baxter.’

As if they were still a couple, as if she hadn’t just had her soul ripped out. Jenny heard Mary breathe and try to regain control.

‘It’s OK,’ she said. It wasn’t OK, it was a stupid thing to say, nothing was ever going to be OK again. ‘Tell me about William.’

So Mary did. She talked about her dead husband, how they met at the dancing on Lothian Road in the 1950s, he’d been in the navy, dashing in his uniform, seen the hydrogen bomb tests over Christmas Island in the Pacific but lived a long life despite that, worked at Ferranti building cockpit instrument panels for fighter planes, raised four children, one of whom was dead already. That made her pause. Jenny couldn’t bear it, she wasn’t cut out for this, didn’t have what Dorothy and Jim had, or Indy. She kept thinking about her own dad in a heap on a metal tray in the room through the back.