7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

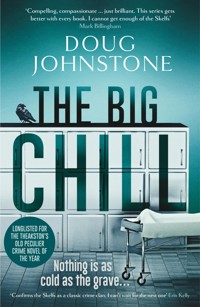

Running private-investigator and funeral-home businesses means trouble is never far away, and the Skelf women take on their most perplexing, chilling cases yet in Book Two of the darkly funny, devastatingly tense and addictive Skelfs series! ***Longlisted for Theakston's Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year*** 'Compelling, compassionate … just brilliant. This series gets better with every book. I cannot get enough of the Skelfs' Mark Billingham 'Brilliantly drawn and blackly comic' Herald Scotland 'Confirms the Skelfs as a classic crime clan. I can't wait for the next one' Erin Kelly 'I LOVE the Skelfs … The only problem with The Big Chill is that you'll devour it so fast you'll feel as bereft as one of the Skelfs' clients. Doug Johnstone has murdered sleep' Val McDermid ____________________ Haunted by their past, the Skelf women are hoping for a quieter life. But running both a funeral directors' and a private investigation business means trouble is never far away, and when a car crashes into the open grave at a funeral that matriarch Dorothy is conducting, she can't help looking into the dead driver's shadowy life. While Dorothy uncovers a dark truth at the heart of Edinburgh society, her daughter Jenny and granddaughter Hannah have their own struggles. Jenny's ex-husband Craig is making plans that could shatter the Skelf women's lives, and the increasingly obsessive Hannah has formed a friendship with an elderly professor that is fast turning deadly. But something even more sinister emerges when a drumming student of Dorothy's disappears and suspicion falls on her parents. The Skelf women find themselves sucked into an unbearable darkness – but could the real threat be to themselves? Following three women as they deal with the dead, help the living and find out who they are in the process, The Big Chill follows A Dark Matter, book one in the Skelfs series, which reboots the classic PI novel while asking the big existential questions, all with a big dose of pitch-black humour. ____________________ 'Exceptional … Johnstone seamlessly presents their stories with depth, elegance, and a delicate touch of wry humor as they get difficult jobs done with grace and kindness. This is a must for those seeking strong, authentic, intelligent female protagonists' Publishers Weekly 'Emotionally complex, richly layered and darkly funny. An addictive blend of Case Histories and Six Feet Under' Chris Brookmyre 'Johnstone's intuitive depiction of this trinity of resilient women is never less than flawless, in this tale punctuated by emotional depth and moments of dark humour...' Raven Crime Reads Praise for The Skelfs series ***Shortlisted for the McIlvanney Prize for Best Scottish Crime Book of the Year*** 'An engrossing and beautifully written tale that bears all the Doug Johnstone hallmarks in its warmth and darkly comic undertones' Herald Scotland 'Gripping and blackly humorous' Observer 'This dark but touching thriller makes for a thoroughly enjoyable slice of Edinburgh noir' Mary Paulson-Ellis 'This enjoyable mystery is also a touching and often funny portrayal of grief, as the three tough but tender main characters pick up the pieces and carry on: more, please' Guardian 'A tense ride strong, believable characters' Kerry Hudson, Big Issue 'They are all wonderful characters: flawed, funny, brave and well set up for a series. I wouldn't call him cosy, but there's warmth to Johnstone's writing' Sunday Times

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 417

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

i

Haunted by their past, the Skelf women are hoping for a quieter life. But running both a funeral director’s and a private investigation business means trouble is never far away, and when a car crashes into the open grave at a funeral that matriarch Dorothy is conducting, she can’t help looking into the dead driver’s shadowy life.

While Dorothy uncovers a dark truth at the heart of Edinburgh society, her daughter Jenny and granddaughter Hannah have their own struggles. Jenny’s ex-husband Craig is making plans that could shatter the Skelf women’s lives, and the increasingly obsessive Hannah has formed a friendship with an elderly professor that is fast turning deadly.

But something even more sinister emerges when a drumming student of Dorothy’s disappears and suspicion falls on her parents. The Skelf women find themselves sucked into an unbearable darkness – but could the real threat be to themselves?

Following three women as they deal with the dead, help the living and find out who they are in the process, The Big Chill follows A Dark Matter, book one in the Skelfs series, which reboots the classic PI novel while asking the big existential questions, all with a big dose of pitch-black humour.ii

iii

THE BIG CHILL

DOUG JOHNSTONE

v

This one is for Val, Mark, Chris, Stuart and Luca.

vi

CONTENTS

1

DOROTHY

Dorothy felt at home surrounded by dead people.

She breathed deeply as Archie drove the hearse through the cemetery gates and along the rutted path that ran round the edge of the small graveyard. Like most cemeteries in the city, Edinburgh Eastern was hidden from public view as much as possible, an anonymous entrance on Drum Terrace, high stone walls enclosing the space. One side was flanked by terraced flats, another by the back of the Aldi on Easter Road. Behind the opposite wall she could see the corrugated-iron roof of a trade wholesalers. Looming over the graves on the south side was Hibs’ stadium, more dirty corrugated iron, a grid of green support beams around the top like a crown.

They crawled round the cemetery, past a graffitied shed, then a skip full of rotten flower bouquets, cellophane shimmering with dew, ribbons flapping in the breeze. She wished the guys who ran this place were more considerate, mourners didn’t need to see the business side of death.

Dorothy had been in the funeral business for forty-five years, it was all she knew. She glanced round at Susan Blackie’s coffin in the back of the hearse, the family car following behind. She looked at Archie, deadpan face, shaved head, neat grey beard. She’d known him for a decade, considered him a friend as well as a colleague, but that had been tested by what happened six months ago. She had uncovered horrifying secrets in her family and the business, and they were still dealing with that. The one thing that gave her peace was this, looking after the dead.

They reached the open grave and pulled over. Dorothy eased out of the passenger seat, her seventy-year-old muscles letting her 2know that yoga wasn’t enough anymore. She stretched her back, angled her hips, small movements so as not to draw attention. A funeral director should be anonymous, if people noticed you, you weren’t doing your job properly.

Archie got out and opened the back of the hearse, removed the wreath from the coffin and placed it to the side. There was comfort in all of this, the correct way of doing things, deference in the way they moved. It was hard for young people, but the older you got the more natural it felt, creating the smallest ripples possible. Dorothy had had her share of ripples recently and she was happy to be back in still waters, helping others pay last respects.

The Blackie family emerged from their car as more family and friends coalesced around the grave. Very little was said, it was almost telepathic, a hand on a shoulder, a tilt of the head, the body language of grief.

Archie and the young driver from the other car rolled the coffin across the rollers and out of the hearse, enlisting the Blackie men to carry it to the grave. They laid it on the plastic grass next to the hole, a large mound of damp dirt to the side. It was rare these days to bury people rather than cremate them, even rarer for the whole ceremony to take place by the graveside. But Dorothy liked it, it was more honest, more connected than seeing a shrouded coffin sink inside a plinth in a cold chapel.

She stood with her hands clasped as the funeral party stood around the grave. She looked at some nearby gravestones, recent additions, engraving still sharp, lots of flowers and photographs. The Skelfs had buried some of these people and she wondered how the bereaved were coping. Were they dealing with it better than she was with Jim’s death? It was half a year now, and it was true what she’d told others for decades, the sharp pain did reduce, replaced by an aching throb. Background emotional noise that gave life a bittersweet edge.

The young Church of Scotland minister said a few quiet words to Gordon Blackie and his sons. They were working-class 3men, buttoned-up and stoic, there would be no wailing and gnashing of teeth today. Plus, Susan Blackie had suffered dementia for years so it felt like she’d left them a long time ago. Death was often a relief, though it was hard to admit that.

The minister began the familiar intonations of the ceremony. Susan’s life was remembered, our fragile nature in the face of the almighty was given a nod. The minister was in his twenties, floppy black fringe that he kept touching. Dorothy wondered how someone went into that profession fresh from school or college. But then she had entered the funeral business at the same age.

She looked around. The oak and beech trees were coming into leaf, the rejuvenation of spring. But there would be no rejuvenation for Susan Blackie. Nevertheless, Dorothy couldn’t help feeling something, a sense of rebirth, a chance to make the world new again.

The highest branches swayed in the breeze, pigeons and crows perched and watching. Dorothy heard the shush of Easter Road traffic mixed with the minister’s words. His voice didn’t have the gravitas for funerals yet, not enough experience. The Blackie men stared stony-faced at Susan’s coffin, as if they could lower it into the ground with sheer willpower.

Dorothy heard a police siren, faint but getting louder. She listened for the change in pitch, the Doppler effect Hannah had explained to her, when the source of the sound travelled away instead of towards you. But it didn’t change, the wailing just got louder, making the minister pause his eulogy.

There was an almighty metallic crash and Dorothy spun round to see the iron cemetery gates buckle and spring from their hinges, clatter into the stone pillars either side and collapse as an old white Nissan careened into the graveyard and pummelled along the gravel path on the south side, rising into the air over bumps and swerving between graves. It was moving at maybe fifty miles per hour, engine a high whine, as the siren got louder and a police car thundered through the cemetery gates in pursuit.4

The Nissan braked and swerved at the bend in the path, fishtailed into a headstone, which fell like a domino. The car straightened and sped up, the police car copying its trajectory round the bend, running onto the grass. The Nissan glanced off two more gravestones and ricocheted across the path, the gravestones tearing chunks from the front bumper, denting the driver’s door.

It was a hundred yards away from the hearse, the family car and Susan’s coffin. The Blackie party stood with eyes wide, Dorothy the same, the minister with his mouth open.

The hearse was blocking the path but the Nissan kept racing towards them, bouncing along, clattering against headstones and thumping over grassy mounds. The police car was behind, lights flashing, siren screaming.

The Nissan was almost at the hearse now as Dorothy felt someone pulling her, Archie was yanking her arm. She stumbled towards a large memorial stone just as the Nissan rushed past her, swerved away from the rear of the hearse, scattering mourners, the Blackie men jumping out of the way. The car clattered into the gravestone next to Susan’s coffin, bounced into the air, then its front end dipped and it landed with a sickening thud halfway in the empty grave, its rear end hanging in the air, wheels spinning.

The police car skidded to a halt a foot from the hearse and its siren stopped. The sudden quiet was disorienting, as Dorothy straightened and ran to the Nissan. She went past Susan’s coffin, which seemed unscathed, to the driver’s side of the car. She hauled at the crumpled door three, four times. Eventually it opened and she leaned in.

Behind the wheel was a dishevelled young man in dirty clothes, with longish hair and an untidy beard. He wasn’t wearing a seatbelt and there was no airbag. He had a long gash across his forehead, which was leaning against a crack in the windscreen. Blood poured from his ear. He was dead, Dorothy knew that look better than anyone. 5

She held the door open, staring at him, as a young police officer arrived behind her. He looked at the Nissan’s driver, eyes wide. He’d obviously not seen as many dead bodies as Dorothy. His face went pale.

Dorothy heard a noise from the back seat. She leaned in, heard the noise again, a whimper. She spotted him, a small border collie with one eye. The dog climbed forward from the back and licked the driver’s head wound, tasting its owner’s blood. It whined and shrank away.

Dorothy turned to the young cop, who was shaking.

‘What the hell?’ she said.

2

JENNY

‘Cheers.’

Jenny smiled at Liam as they both hit their drinks, a double Hendricks for her, a pint of Moretti for him. Maybe they should’ve been on champagne, given they were celebrating his divorce, but who pays pub champagne prices? Anyway, divorce is always melancholic, Jenny knew that well. Mingled with the relief was the admission of defeat. You weren’t good enough to make the marriage work, even if the other person was a piece of shit and you were well rid of them.

She looked around The King’s Wark. Ancient, rough stonework, large fireplace, mismatched wooden tables and chairs. Just a handful of drinkers this time of day, suits from Pacific Quay on early lunch.

‘So you’re young, free and single again,’ Jenny said, deadpan.

Liam pulled at the skin under his eyes. ‘I haven’t been young for years.’

‘You’re younger than me.’

He did look tired, the divorce had taken its toll over the last six months. But he was still handsome, those green eyes, the flecks of grey through his black hair. He still looked after himself.

He smiled. ‘That’s not hard.’

‘Hey.’ She faked outrage, punched his shoulder, felt the solid muscle.

She looked around the pub. ‘Nice touch, coming here.’

‘This is our place.’

It hadn’t been a conventional way to meet. Jenny was hired by Liam’s now ex-wife, Orla, to find evidence he was cheating. Jenny had just started working for her mum, helping out at both the 7Skelf’s funeral director’s and private investigator’s. She had no idea what she was doing, but she followed Liam to his artist’s studio round the corner, then sat in this pub watching him. Which is where she saw Orla’s failed sting attempt – she’d hired an escort to seduce him, to entrap him so that Orla could file for divorce. Jenny sprung a trap of her own, got evidence that Orla was fucking her gardener, which she presented to Liam. Again, right here in The King’s Wark.

It wasn’t the most auspicious start, but Jenny’s own marriage to Craig began with true love and wound up with her husband lying and cheating, so maybe this was better.

‘Thanks for everything,’ Liam said.

Jenny shook her head. ‘It was just a few pictures.’

‘I’m not talking about the evidence,’ he said. ‘I’m talking about us.’

Jenny looked away. It was embarrassing how open Liam was. Maybe because of his creative side he was in touch with stuff that Jenny and most of her generation kept hidden. She was raised to shrug and say ‘whatever’, hated direct emotional engagement. That’s what made her bad at the funeral business. She should be helping Mum right now, but she found it difficult to handle the emotions that spilled over at funerals. And anyway, Dorothy and Archie would have everything under control.

Liam took her hand and she resisted the urge to pull away. Ever since Craig, she struggled with this. Maybe she should go to therapy like Hannah, to help her cope. But therapy wasn’t in her DNA, the idea of talking to a stranger about the fucked-up things in her head made her teeth itch.

‘How’s Hannah?’ Liam said, as if reading her mind. Maybe it was obvious she was constantly worried about her daughter. Fuck, who wouldn’t be? Hannah’s dad had killed one of her best friends, and tried to kill Jenny and Dorothy too. When Larkin said your mum and dad fuck you up, did he have that crazy shit in mind?

Jenny sighed. ‘I don’t know.’ 8

‘She’ll be OK.’

‘I wish I had your confidence.’

‘I have plenty of confidence in your family, less in myself.’

‘God, I’m fed up telling you.’

‘It’s fine,’ Liam said, smiling. ‘We have confidence in each other, just not ourselves. That’s Gen X, right?’

He was so honest it was painful. How had the world not crushed this man already? Six months after finding out his marriage was a sham, he was here in the pub smiling and joking. When Jenny’s divorce came through ten years ago, she curled up in a ball at home for years afterwards. Craig moved on to a new woman, new family, new life. How do you square that shit away?

Liam took a drink and narrowed his eyes. He knew her already, what her moods were, when she was shrinking into herself.

‘Hannah and Dorothy will be fine,’ he said. ‘You’re the strongest women I’ve ever met. If anyone can handle things, it’s the Skelfs.’

Jenny drank and shook her head, felt the burn of the extra gin in her tonic. She needed that edge to hold on to. Hannah was seeing a counsellor, Dorothy seemed to have found peace in the funeral work. But where did that leave Jenny? A dead dad, a murderous ex-husband, no home of her own, working two jobs she couldn’t do very well. She looked around the pub and out of the window. It was a beautiful spring day and the Water of Leith was shimmering in the sun. She had a handsome, smart man with her, and she had her family.

She turned back to Liam and made a face. ‘So today is the first day of the rest of your life.’

Liam rolled his eyes. ‘Today is always the first day of the rest of your life. Until you die.’

‘Cheery.’

Liam raised his glass. ‘Cheers.’

They drank, and Liam put his glass down.

Jenny leaned in and kissed him, squeezed his hand on the table, tried to feel sexy, wanted. She pulled away and drank. 9

He smiled. ‘What was that for?’

‘Just a Happy Divorce kiss.’

He sipped his pint, keeping his eyes on her. ‘I should get divorced more often.’

‘I wouldn’t recommend it.’

They were comfortable with this level of flirting and banter. They’d been seeing each other for the last couple of months, ended up in bed a handful of times, but hadn’t discussed what this was yet. Jenny was scared that if they did it would vanish in a puff of smoke. They were both licking their wounds, for God’s sake. But Jenny wanted to be seen, still wanted to be a sexual being, wanted to turn him on. And he certainly turned her on.

She thought about what he’d said before, that today was always the first day of the rest of your life. She liked that. At least until you die. But she lived around death every day, bodies in the embalming room, the viewing rooms, the chapel. Deceased and bereaved everywhere you looked in a funeral home.

Jenny watched Liam drink, delicate movements, considered, unassuming. She suddenly wanted to take him home to bed.

‘Let’s get out of here,’ she said.

‘And do what?’

Jenny’s phone rang in her bag as she took a final swig of her gin. She fished it out. ‘Hey Mum, how was the funeral this morning?’

3

HANNAH

The counsellor’s office was annoyingly jaunty, bright yellow seats, a lurid green desk. Outside the window Hannah saw the Meadows, students soaking up sunshine on the grass, mums with little kids in the play park, tennis players thwacking balls across the courts. To the right was Bruntsfield Links and she could just make out the Skelf house beyond that. The irony of it, while undergoing counselling she could see the place she chased her dad covered in blood.

Out the other window of Rita’s corner office was George Square and the dome of McEwan Hall, where Hannah would graduate in a year’s time, maybe. Recent grades were not good. She could’ve taken a year out, given everything that happened, but she would’ve gone mad with nothing to keep her occupied.

‘What are you thinking about?’ Rita said.

Hannah turned. The counsellor was about the same age as her mum, purple hair chopped short, black frilly top, leggings, Doc boots, biker jacket on the back of her chair. Hannah wondered how she came to work for Edinburgh Uni, talking students through their crises. Most of them would be stressing over exams, depressed about breaking up with a boyfriend or girlfriend, confused about their sexuality. Hannah could trump that.

‘You mean apart from the fact my dad killed my friend, who was carrying his baby, then tried to kill my mum and gran?’ she said.

Rita gave her a look like a kicked puppy.

‘I’m sorry,’ Hannah said.

Rita held out her hands. ‘It’s what I’m here for. You’ve been through a lot. Anger is reasonable.’11

Hannah shook her head. ‘I’m not angry, that’s the thing, I’m just tired. So fucking tired.’

Rita nodded and crossed her legs. ‘Again, totally reasonable. I’d be tired. Anyone would be tired in your situation.’

Hannah’s girlfriend, Indy, had floated the idea of therapy or counselling a month after everything happened with Craig, when it was clear Hannah was struggling. Dorothy suggested a private shrink but Hannah refused. They cost a ton of money, and Hannah believed that talking to one person about your shit was the same as talking to anyone about it. Would a psychiatrist wave a magic wand and make it all go away? So here she was talking to an ageing rock chick who no doubt had a bunch of her own unresolved shit to deal with.

Hannah had never told Rita they had a view of the crime scene from her office window. Normally Hannah liked talking, she’d grown up connected to the world in a way Rita’s generation could never grasp. But she didn’t want to talk about this. What difference did it make? Mel was still dead, her dad was in prison, and everyone still carried the scars.

‘Have you heard of the many-worlds interpretation?’ she said.

Rita tilted her head. ‘No.’

‘But you know about Schrödinger’s cat?’

Rita frowned. ‘Something about a cat in a box that’s alive and dead at the same time.’

Hannah smiled. ‘Kind of. It’s quantum mechanics. On a subatomic level, a particle is in an indeterminate state until it’s observed. So what if you scale that up? Put a cat in a box with a flask of poison and a radioactive source. If the source decays, a quantum event, the flask breaks and the cat is poisoned. But until you open the box you don’t know whether the source has decayed, so the cat is both dead and alive.’

‘OK.’ Rita dragged the word out.

‘It’s a paradox, but there’s a way out of it.’

Rita waved a hand. 12

‘The many-worlds interpretation says that whenever you open the box, the universe splits, so in one universe the cat is dead, and in a parallel universe somewhere, the cat is still alive. That happens with every observation.’

‘Right.’

Hannah looked out of the window at her gran’s funeral home in the distance. Indy was working at reception there, waiting for Hannah to finish, waiting for her to move on with her life. Waiting for a snog.

Hannah turned to Rita who was fingering a big hoop earring. ‘So do you think, in a parallel dimension, Mel is still alive, about to have a baby, my half-sister?’

‘That’s an interesting way to look at it.’

Hannah sighed. ‘There’s a problem. Say you were inside the box instead of the cat. Then you would observe if the source decayed and the waveform collapses. You’d be dead. That’s quantum suicide. But the many-worlds interpretation goes the other way. Since you can only observe outcomes where you’re alive, by definition, then you stay in the universe where you keep surviving. Quantum immortality.’

Rita was frowning, lines across her forehead. ‘You’ve lost me.’

‘If you always end up in the universe where you survive, doesn’t that mean you can do anything you want?’

‘I don’t think that’s helpful.’

‘Maybe that’s what my dad thought,’ Hannah said. ‘Maybe he thought he could just do anything he liked and get away with it.’

Rita sighed. ‘It doesn’t take quantum physics for men to think they can get away with stuff.’

Hannah smiled. She imagined being a cat in a box, waiting to die. ‘And I’m half him, that’s the way genetics works.’

‘That’s not how life works.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘I’m nothing like my parents.’ Rita smiled as something occurred to her. ‘Let me tell you about my mother.’ 13

‘What?’

‘It’s a line from Bladerunner. Ever seen the original Bladerunner?’

Hannah shook her head. ‘Just the recent one.’

‘They catch a replicant and interview him, ask about his mother. He says “let me tell you about my mother” then shoots his interviewer under the desk.’

Hannah smiled and lifted her hands. ‘No gun.’

‘You’re not a replicant,’ Rita said.

‘But I don’t know that, they had implanted memories, right? If that’s true, can you erase some of mine?’

‘If you erase your memories, don’t you erase yourself?’

‘I don’t know.’

Rita smiled. ‘This is more like an ethics class than a counselling session. We’ve kind of gone off topic.’

‘Did the replicants have morals?’ Hannah said.

‘I think they were programmed into them.’

‘So they couldn’t do whatever they wanted.’

‘No more than any of us.’

Hannah shook her head as her phone rang.

‘Sorry,’ she said, pulling it from her pocket. ‘I’d better take this.’

She pressed reply. ‘Hey, Mum.’

‘Something’s happened,’ Jenny said down the line.

4

JENNY

Jenny handed cash to the taxi driver and stepped out. The sight of the house gave her a trill in her stomach, like always, throwing up childhood memories. A three-storey Victorian block with low additions to the side that housed the embalming room, body fridges, coffin workshop and garage for the hearse. The funeral business she’d escaped from decades ago, only to be sucked back in six months ago when her dad died. So she was living here again, haunted by memories, haunted by the thousands of dead who’d passed through the place.

She went in the side door and through to reception, where Indy was at the desk. Hannah’s beautiful girlfriend, just one of the strays Dorothy had accumulated at the funeral home over the years. She’d turned up four years ago to arrange her parents’ funeral, wound up helping out around the place, a natural at dealing with people, Hannah included. She’d dyed her hair again since Jenny last saw her, a green that set off her dark skin.

‘Archie told me what happened,’ Jenny said.

Indy shook her head. ‘Crazy.’

‘Where’s Mum?’

Indy nodded upstairs. ‘In the ops room. She’s fine.’

Jenny headed up. The ops room was where they ran the funeral and PI businesses, but it was also their kitchen and dining room, where she’d had countless family meals. She reached the doorway and saw Dorothy at the sink, spooning cat food into a bowl.

‘Mum, Archie called me, are you OK?’

Dorothy turned and smiled, placed the bowl at her feet with one hand touching her back.15

Jenny went in and stopped when she spotted the dog.

‘Who’s this?’

The collie snuffled at the food, then a couple of licks and it began eating. It looked up between bites as if the food might be taken away.

Dorothy crouched and tickled his ear. ‘I don’t know his name, no collar.’

‘Where did you find him?’

‘In the car.’

‘What?’

‘The accident this morning, you said Archie told you.’ Dorothy stood up and reached for a cupboard, took out two glasses and a half-empty bottle of Highland Park. ‘I need a drink.’

She poured two measures, handed one to Jenny, then sat at the table.

Jenny watched her movements, slow and careful. She hadn’t been the same since everything with Craig. He’d stabbed Jenny in this room, then beaten and choked Dorothy, who’d stabbed him in self-defence.

Jenny was left with a large scar on her belly and night terrors. Dorothy’s bruises took a long time to heal. Before, despite being seventy, she had energy, moved with grace. Now she was tentative, as if the world could really harm her, aware she wasn’t going to last forever. It broke Jenny’s heart to see her mum like this.

She sipped her whisky, pulled out a chair and sat, placed a hand on her mum’s. ‘What happened?’

‘Archie saved me,’ Dorothy said, looking out of the window.

Bruntsfield Links was putting its spring show on, the trees filling out and dancing in the breeze, a few souls sitting on the grass, happy to be through another winter. The ancient dead buried below were pushing up new grass, her dad’s ashes down there too amongst the plants and flowers, worms and bugs.

Jenny looked from the window to the two large whiteboards on the other wall. One for funerals, the other for PI cases. The 16funeral one was busy, half a dozen jobs on the slate, bodies in the fridges downstairs or waiting to be collected, or already embalmed and waiting for the final send-off. The PI work had been steady recently too, mostly marital stuff, which Jenny found she had a knack for since Liam.

Jenny turned to Dorothy. ‘He said there was a police car chase?’

Dorothy exhaled. ‘That’s right.’

‘In the graveyard?’

‘Yes.’

‘What the hell?’

‘That’s what I said.’

‘Are you OK?’

‘I’m fine, Archie pulled me out of the way. No one in the Blackie party was injured, including the deceased. But we’ve had to postpone the funeral, the grave is a crime scene.’

‘What were they thinking, chasing him into a cemetery?’

Dorothy took a drink. She never used to touch whisky before Jim died, it was always his drink, but she’d claimed it as her own since he was gone, maybe the taste was a memory.

‘The man in the car died,’ Dorothy said.

Jenny shook her head. ‘Why were they after him?’

‘Car was stolen, that’s all.’ She drank. ‘I think he was homeless. The car had a sleeping bag and an old backpack in it.’ Dorothy nodded at the collie. ‘And this guy.’

‘Why is he here?’

‘Where else could he go?’

‘The police should deal with him.’

Dorothy smiled. ‘The police officer was just a baby, poor thing. He was in shock. I had to make him do breathing exercises. Then I got the dog out of the car, put him in the hearse. The police don’t want to deal with a dog.’

‘But the dog might belong to someone.’

Dorothy nodded. ‘I’ve spoken to Thomas about it.’

This was her friend, a police inspector over at St Leonards. 17She’d helped him bury his wife a few years back, he’d helped her with PI cases since.

Dorothy drank again. ‘I’ll look after him until we find his home, if he has one.’

There was a hiss from the doorway and Jenny saw Schrödinger there, back arched, staring at the collie. The ginger cat was another of Dorothy’s strays, she attracted those who didn’t have anywhere else.

Hannah appeared in the doorway and scooped the cat into her arms. Schrödinger stayed alert, eyes on the intruder.

‘Gran, are you OK?’

Dorothy sighed. ‘I don’t need any fuss.’

Schrödinger squirmed from Hannah’s arms and landed on the rug. Jenny saw where they’d tried to clean up the blood from that night. The rug was red and patterned so the blood was easy to hide.

‘Who’s this guy?’ Hannah said, pointing at the collie.

Jenny looked at her daughter. Her black hair needed a wash and she looked tired. This had been hard on everyone, Hannah most of all.

Jenny took a sip of whisky. ‘He belonged to the guy driving the car.’

‘Belonged?’

Jenny glanced at Dorothy, who was staring out of the window again.

‘The driver died,’ Jenny said.

‘Holy shit.’ Hannah stroked the dog, Schrödinger hissing in the doorway.

‘Take it easy,’ Hannah said to the cat. She looked up. ‘So we’ve got this guy until we find his family?’

‘If he has one,’ Dorothy said.

Hannah checked for a collar, tickled under his chin.

‘He got a name?’

Jenny shook her head. 18

Hannah stood and thought, looked from the dog to the cat.

‘He can be Einstein,’ she said. ‘Einstein and Schrödinger never got on.’

Indy appeared at the doorway with a look. ‘Someone’s downstairs.’

‘A funeral?’ Dorothy said.

‘No.’

‘A case?’ Jenny said.

Indy shook her head and threw a look of apology around the room, landing on Hannah. ‘It’s your stepmum, Han, she wants to speak to all of you.’

For years Jenny had built up Fiona as a nemesis, the perky little blonde who lured her husband away. That was insane, of course, Craig was the one having an affair back then, and anyway, Jenny was lucky the way things turned out. She’d thought about Fiona in the last six months, how it would be for her, her husband in prison, a murderer, a cheat. Worse still, he and Jenny had been fooling around before all the craziness. They were all tricked by the same man, so Fiona wasn’t the enemy. But that still hung in Jenny’s mind, anxiety creeping up her spine at the thought of the woman downstairs.

‘Bring her up,’ Dorothy said, touching her forehead.

Hannah held the kitchen worktop, breathing deep, eyes closed.

Jenny heard footsteps, and there she was. Fiona was beautiful, same age as Jenny. She was small but expertly put together, both her figure and her smart suit, like a successful solicitor with an edge of sex appeal.

‘Come in,’ Dorothy said, waving a hand.

Fiona hesitated, looked at Hannah.

Hannah lived with Jenny after the divorce, but she’d spent weekends with Craig, Fiona and Sophia, her cute wee half-sister.

‘Hi, Han,’ she said.

‘Hey.’

Fiona looked around. ‘So this is where it happened?’ 19

She meant Craig’s face-off with the Skelf women.

‘The crime scene, one of them at least,’ Jenny said, then regretted it. Mel had died, fuck’s sake, this wasn’t a joke.

‘It can’t have been easy to come here,’ Dorothy said. ‘Would you like a drink?’

She waved the Highland Park in the air. Jenny wished her mum wasn’t so calm. It was irrational, but Jenny wanted to hold a grudge against someone, and Craig was in Saughton Prison, so Fiona would do.

Fiona nodded and entered like a deer into a clearing. Jenny imagined her in rifle crosshairs.

‘How’s Sophia?’ Hannah said.

Fiona scratched at her neck. ‘OK. She doesn’t understand, misses her dad.’

That made Jenny think, the ripples in all their lives.

Dorothy handed Fiona a whisky and she took a gulp. Jenny saw bags under her eyes, a nervous twitch in the corner of her mouth. She was thinner than Jenny had seen her looking on social media.

Fiona looked at the whiteboards, scribbles and scrawls, deaths to be negotiated, mysteries to be solved. She took another drink, stalling.

‘How are you all?’

‘The wounds have healed,’ Jenny said. Her hand went to her scarred stomach, touched the skin underneath her T-shirt.

‘I didn’t mean that,’ Fiona said.

‘Why are you here?’ Jenny said.

‘Jenny,’ Dorothy said.

It took Jenny back to being a kid, the reprimand in her mum’s voice, a shiver of shame up her neck.

‘This isn’t easy for anyone,’ Fiona said. ‘He refuses to sign the divorce papers, he’s still my fucking husband, think about that.’

Jenny thought about it. They both had daughters by the same bastard, they should be sisters-in-arms. But it wasn’t that easy.

Fiona took a drink. ‘I wanted to tell you in person. He’s 20changed his plea. From guilty to not guilty on the grounds of diminished responsibility.’

Hannah’s grip on the worktop tightened, she rocked back and forth. ‘Are you serious?’

‘He’s claiming he was crazy?’ Jenny said.

Fiona shook her head. ‘I couldn’t believe it when the solicitor told me.’

Hannah pushed herself away from the worktop and balled her hands.

‘But he admitted it,’ she said. ‘He admitted it all to the police.’

Fiona shrugged. ‘Says he wasn’t in his right mind. He’s pushing for a quick trial now too.’

Jenny couldn’t get her head around it. ‘After all this time? What’s he playing at?’

Dorothy had been silent through all this. ‘He can’t think he has a case.’

Fiona swallowed hard. ‘It’s not about that.’

‘Then what?’ Hannah said.

Fiona looked around the women. ‘He wants to see us in court. The solicitor thinks he’ll call us all as witnesses.’

‘But we’ll testify against him,’ Jenny said. ‘He must know that.’

Fiona downed the remains of her whisky, shivered from the hit.

‘He doesn’t care,’ she said. ‘He wants to punish us.’

5

DOROTHY

St Leonards police station was a bland modern brick block sitting amongst student flats in the Southside. Dorothy saw Salisbury Crags to the right, the cliffs leering over the southern part of the city. She went inside the station and waited at reception, but she’d barely sat down when Thomas appeared.

She was struck, as always, by how he carried himself – upright, confident but never arrogant. It couldn’t be easy, being a black man in a Scottish police force was as rare as hens’ teeth, but he walked as if he knew his place in the world.

‘Dorothy, are you OK?’ Still the trace of Swedish in his voice despite living here for twenty years. That was another reason she liked him, they were both immigrants in this strange country with its black humour and deep-fried food. Now they were both widowed, another thing in common.

He pulled her in for a hug, more than perfunctory, and she let herself be held, sank into it. Eventually she pulled away. ‘Don’t fuss.’

Thomas looked her in the eye. ‘I like fussing over you.’

He was fifteen years younger than her but there was something unspoken between them. Never acted upon, she’d been happily married until six months ago. Since then she’d felt untethered from her previous life. Maybe it was time to do some tethering. Who was she kidding? She was seventy years old, that stuff didn’t happen to women her age.

‘Come through,’ he said, holding the door.

They went up to his office, a better view of the Crags from here. It was kicking on for sunset, the sky was a bruise behind the blade 22of the cliffs, a few dots moving on the skyline, tourists up for the views.

Laid out on a table against the far wall were the joyrider’s belongings. The grubby sleeping bag and the rucksack, its contents alongside.

‘How’s the young officer?’ Dorothy said.

Thomas shook his head. ‘He’ll be OK.’

‘He was in shock.’

‘Understandable. But he was to blame too.’

‘Don’t be hard on him. He needs support.’

Thomas shrugged. ‘He’ll get it. But there will be an enquiry. He didn’t follow procedure.’

‘What happened?’

Thomas leaned against his desk. ‘He saw the car parked somewhere it shouldn’t have been. Ran the plates and realised it was stolen. When he approached the vehicle it took off, so he went after.’

‘Through a graveyard?’

Thomas rubbed at his forehead. ‘He’s only been with us a few months.’

‘Poor guy.’

‘Dorothy, he could’ve killed you, or anyone else at the funeral.’

‘He didn’t, though.’

‘Only through dumb luck.’ Thomas waved at the table of stuff. ‘And if he hadn’t kept after him, our joyrider would still be alive.’

Dorothy walked over to the table. The sleeping bag was filthy and ragged, the zip broken, a hole where the stuffing poked out. She ran a finger across it.

‘Do we know who he was?’

‘No ID in his possessions. We’ve compared his picture to local missing persons, no match.’

‘DNA?’

‘A sample is in the system, but if we don’t have him on file we won’t get a hit.’ 23

Dorothy looked at the rucksack. It was a decent brand but ancient, frayed around the zip, worn through at the corners, stains on the material. She looked over its contents, a filthy jumper, skanky boxer shorts and socks. Heroin works, syringe, belt, spoon, cotton wool, lighter. All used. An A6 notebook with puckered pages from water damage. A single photograph of him with a woman.

She picked it up. He looked younger, no beard, light-blue eyes. He wore a hoodie and crucifix, one ear pierced. The woman was the same age, early twenties, short blonde hair, sharp nose. They were up a hill, a view of Edinburgh and the Forth spread out behind them.

‘Arthur’s Seat?’ Dorothy said.

‘I think so.’

Dorothy flipped the picture over but there was nothing on the back.

‘You could put this out, see if the woman comes forward.’

Thomas nodded. ‘If the DNA doesn’t come through.’

‘He was homeless.’

‘Looks like it.’

‘So maybe check hostels and social care.’

Thomas took the picture and studied it. ‘We don’t have the resources, you know that.’

‘If he was a murder victim or suspect, you would.’

‘This wasn’t murder, it was an accident. A stupid, avoidable accident.’

Dorothy opened the notebook. A manic pencil scrawl. She narrowed her eyes and tried to read. Words about hate, conspiracy, the system keeping people down. It wasn’t sentences, just ramblings.

‘Can I take this?’

Thomas frowned. ‘One of our guys has been through it. He doesn’t think there’s anything to identify him.’

‘Still.’ 24

‘OK, but don’t lose it.’

Dorothy smiled. ‘And can I get a copy of the photograph?’

‘I’ll email it.’

‘Is his body at the City Mortuary?’

Thomas nodded. ‘Post-mortem is tomorrow. I’m not expecting much but toxicology might throw up something.’

‘Can I see him?’

Thomas still had the picture in his hand. He looked from it to Dorothy, sizing her up. ‘You know Graham Chapel down there, right?’

‘Of course.’

‘Tell him I said it was OK.’

‘Thank you.’

Thomas put the picture down then placed a hand on Dorothy’s elbow, his face softening. ‘What’s your interest in him?’

‘Are you serious? He literally crashed into my life.’ Dorothy touched the edge of the notebook. ‘We all come from somewhere. I want to know who he was.’

Thomas gave her elbow a rub then let go. ‘I get that. But remember last time you got your teeth into something like this. After Jim … passed. You can get carried away.’

She’d called in favours with Thomas to work out her dead husband’s secrets, only to realise they were worse than she could’ve imagined. And Thomas didn’t even know the whole story – only her girls and Archie knew what really happened.

‘That was different.’

‘Was it?’ Thomas said.

‘It was personal.’

‘And this isn’t?’ Thomas gave a sceptical smile. ‘He almost killed you.’

Dorothy looked at the photograph again.

‘I just want to know who he is.’

6

HANNAH

She stared at her laptop screen. She’d got the title, ‘Melanie Cheng Memorial’, and the cursor blinked at her from the next line. Anxiety swelled from her belly to her chest, and she breathed deeply and looked out of the window.

The view was out to the back of the flats, a patchwork of small lawns, a cluster of birch trees, and thirty other living-room and bedroom windows. She was reminded of that Hitchcock film Gran liked, imagined seeing a murder across the road. But all she could see was an old man bent over a stove, a young couple building Lego with their son, students staring at phones, their faces lit like figures in a Renaissance painting. Everyone getting on with life, the little disappointments and triumphs, the small gestures of comfort or annoyance, the incremental moments of time that accumulated into experience.

She felt stuck in comparison. For her, those moments weren’t accumulating, they were slipping away, one flash of panic to the next, one depressive slump bleeding into another, the constant anxiety. And this blank page in front of her wasn’t helping.

‘You don’t have to do it.’

Hannah turned to see Indy in the doorway, her face a balance of love and worry. Hannah felt her own twinges of love and worry. She was sick of feeling shit because of what happened, and Indy had been so supportive through everything. But it was crap that she had to be supportive, that Hannah needed nursing, when all she wanted to do was throw Indy onto the bed and kiss her, or go to the park and have a picnic, or sit in a café over brunch and taste each other’s food.26

‘I do,’ Hannah said, looking at the screen.

Indy came over and placed her hands on Hannah’s shoulders. ‘It’s too much stress.’

‘I want to do it. We’re supposed to celebrate Mel’s life and we were her best friends.’ Hannah put a hand on Indy’s. ‘How do you do it, how do you cope?’

‘You know it’s different. With me it’s just grief, with you it’s more complicated because of your dad.’

Hannah had done the reading, on top of the grief there was guilt that her dad had killed Mel. And survivor guilt too, that she was alive when her friend wasn’t. She was to blame, of course, because if she had never been friends with Mel then Craig wouldn’t have met her. But how far back do you go with cause and effect? She preferred the quantum world, where cause and effect were looser, time didn’t run at the same rate, where her friend was still alive and nursing her new baby.

Indy leaned down and kissed Hannah, and she felt a shiver. She was glad she still got that, despite everything, that she was still turned on by her girlfriend.

She pulled away eventually.

Indy pointed at the laptop. ‘Just speak from the heart. Whatever you say will be great.’

It’d taken six months for the physics department to get around to this memorial for Mel, and Hannah was surprised they’d done it at all. It was complicated by departmental politics for a start. If they did a memorial for Mel, did they need one for Peter too? Hannah presumed they didn’t want to go there, given he was having an affair with one of his students, was thrown out by his wife, suspended by the department, then hanged himself. That’s the kind of thing that gives a physics department a bad name.

But one of the elderly professors, Hugh Fowler, insisted that Melanie’s life should be honoured by the department. Hugh was that peculiar creature of science departments, a doddering old guy 27who’d spent his life in academia, a kindly geriatric who never seemed to work but never retired either.

Hugh had contacted Hannah after a tutorial one day and asked if she would come into the office. He wanted a memorial for Mel, would she speak at it? So here she was the night before, staring at a blank screen. And it was worse because Mel’s family was coming down to Kings Buildings tomorrow. Hannah didn’t need that pressure on top of everything else.

Her phone rang. It was a mobile number, not in her contacts. No one ever called her except Mum and Gran. Probably just some marketing thing, but something made her curious and she pressed reply.

‘Please don’t hang up.’

Blood rushed to her face and she couldn’t breathe. She struggled to swallow as panic snaked up her throat and into her mouth.

Indy frowned and gave her a look.

‘I need to explain,’ the man said. The man she’d known all her life, the man she’d last seen when she stood over him on Bruntsfield Links, as he bled out on the grass, admitted what he’d done, telling her he wanted to die. Her dad.

‘How dare you,’ Hannah said, her voice and hand shaking.

‘I wasn’t myself,’ Craig said.

‘You can’t call me. You don’t get to speak to me.’

She hung up. Tears in her eyes as she let out a shaky breath.

A look of realisation spread across Indy’s face. ‘No.’

Hannah looked wide-eyed.

‘You’re fucking kidding me,’ Indy said. ‘Babes.’

Hannah shook her head and tears dropped onto her laptop. She felt Indy embrace her, trying to comfort her.

‘How can he just call you from prison?’ she said.

Hannah couldn’t speak, the sound of his voice in her head, the sight of him on his knees in the dark, blood pouring from his chin and chest. She wished he’d died, all of this would be easier. 28

‘Why now?’ Indy said.

Hannah extricated herself from the hug, wiped at her face. ‘Maybe it’s the plea thing.’

‘Diminished responsibility is a joke.’

‘I know.’

Indy nodded at the phone, like a radioactive source glowing on the desk. ‘What did he say?’

‘He wanted to explain.’

‘What is there to explain?’

‘He said he wasn’t himself.’

Indy shook her head, angry now. ‘You need to tell the police and the lawyers.’

Hannah looked at Indy, the intensity of her girlfriend’s stare too much. She turned to look outside at all the people living their lives in the flats opposite, the crows in the trees, the vapour trail from a jet high in the darkening sky, a plane full of people escaping their lives for a moment.

‘Tell them what?’ she said.

7

DOROTHY

Dorothy sat behind the drum kit, her beautiful sunburst Gretsch, and tried to focus on the music through her headphones. It was early Biffy Clyro, full of sudden changes, dynamic bursts, odd time signatures. She wanted something to challenge her, something forceful too, nothing with too much feel. But it wasn’t working. She kept thinking about that poor kid in the driver’s seat, his cut forehead, blood, blank stare. No ID, few possessions, just a stolen car and a one-eyed dog.

She stumbled over a middle eight with lots of random stop-starts, her sticks clacking against each other. She never got back into the rhythm, unsure of herself. Behind the kit was usually a place she could be in control, but not today.

Where was Abi? She was already fifteen minutes late for her lesson. She loved drumming, never missed a lesson without sending a dozen WhatsApp messages of grovelling apology. Dorothy had fewer students since she’d taken over Jim’s work at the funeral business, but she’d kept on a handful, all girls, and she loved that. In her own small way she was a role model – an old Californian woman bashing her way round the toms, back to the hi-hats, into syncopated snare trills.