5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Skelfs

- Sprache: Englisch

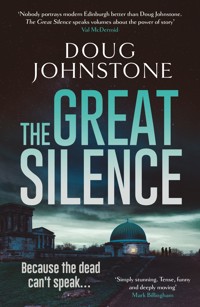

The discovery of a human foot in an Edinburgh park, the inexplicable circumstances of a dying woman, and the missing daughter of Jenny's violent ex-husband present the Skelf women with their most challenging – and deadly – cases yet… Book THREE in the addictive The Skelfs series! 'Simply stunning. Tense, funny and deeply moving' Mark Billingham 'If you loved Iain Banks, you'll devour the Skelfs series' Erin Kelly 'Nobody portrays modern Edinburgh better than Doug Johnstone. The Great Silence speaks volumes about the power of story' Val McDermid ______________ Keeping on top of the family funeral directors' and private-investigation businesses is no easy task for the Skelf women, and when matriarch Dorothy discovers a human foot while walking the dog, a perplexing case presents itself … with potentially deadly results. Daughter Jenny and grand-daughter Hannah have their hands full too: The mysterious circumstances of a dying woman lead them into an unexpected family drama, Hannah's new astrophysicist colleague claims he's receiving messages from outer space, and the Skelfs' teenaged lodger has yet another devastating experience. Nothing is clear as the women are immersed ever deeper in their most challenging cases yet. But when the daughter of Jenny's violent and fugitive ex-husband goes missing without trace and a wild animal is spotted roaming Edinburgh's parks, real danger presents itself, and all three Skelfs are in peril. Taut, dark, warmly funny and unafraid to ask big questions – of us all – The Great Silence is the much-anticipated third instalment in the addictive, unforgettable Skelfs series, and the stakes are higher than ever. ______________ 'This is their third outing and the stories get better each time … Told with a wry humour and affection, the novel underlines just how accomplished Johnstone has become' Daily Mail 'The power of this book lies in the warm personalities and dark humour of the Skelfs, and by the end readers will be just as interested in their relationships with each other as the mysteries they are trying to solve' Scotsman 'Remarkable' Sunday Times Crime Club STAR PICK 'Keeps you hungry from page to page. A crime reader can't ask anything more' The Sun 'Mysteries aplenty … a poignant reflection on grief and the potential for healing that lies within us all. A proper treat' Mary Paulson-Ellis 'A thrilling, atmospheric book, set in the dark streets of Edinburgh. That great city really came alive for me in this gripping tale. Move over Ian Rankin, Doug Johnstone is coming through!' Kate Rhodes 'An unstoppable, thrilling, bullet train of a book that cleverly weaves in family and intrigue, and has real emotional impact. I totally loved it' Helen Fields 'This enjoyable mystery is also a touching and often funny portrayal of grief ... more, please' Guardian 'Wonderful characters: flawed, funny and brave' Sunday Times 'Exceptional … a must for those seeking strong, authentic, intelligent female protagonists' Publishers Weekly The Skelfs series has been: ***Shortlisted for the McIlvanney Prize for Best Scottish Crime Book of the Year*** ***Longlisted for Theakston's Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year*** ***Shortlisted for Amazon Publishing Capital Crime Thriller of the Year***

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 420

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Keeping on top of the family funeral directors’ and private-investigation businesses is no easy task for the Skelf women, and when matriarch Dorothy discovers a human foot while walking the dog, a perplexing case presents itself … with potentially deadly results.

Daughter Jenny and grand-daughter Hannah have their hands full too, when the mysterious circumstances of a dying woman lead them into an unexpected family drama, Hannah’s new astrophysicist colleague claims he’s receiving messages from outer space, and the Skelfs’ teenaged lodger has yet another devastating experience.

Nothing is clear as the women are immersed ever deeper in their most challenging cases yet. But when the daughter of Jenny’s violent and fugitive ex-husband goes missing without trace and a wild animal is spotted roaming Edinburgh’s parks, real danger presents itself, and all three Skelfs are in peril.

Taut, dark, warmly funny and unafraid to ask big questions – of us all – The Great Silence is the much-anticipated third instalment in the addictive, unforgettable Skelfs series, and the stakes are higher than ever.

THE GREAT SILENCE

DOUG JOHNSTONE

This one is for Karen Sullivan, who gave the Skelf women a home.

CONTENTS

1

DOROTHY

She would never get used to picking up Einstein’s shit.

The collie squatted, back legs shivering, then scuffed the grass with its paws and wandered off across Bruntsfield Links, following an early-morning scent.

Dorothy got a poo bag from her pocket and pushed her hand into it. Her back ached as she bent to pick up the crap and she winced at the warmth of it through the bag. The smell came to her and she felt bile rise in her throat as she flipped the bag around and tied it shut.

She placed a hand to her spine as she straightened, rolled her neck, tried to ease the night-time knots. She used to do coffee and yoga first thing every day until the dog crashed into her life a year ago. Now Einstein licked her face to wake her at stupid o’clock, especially in the summer when the sun rose so early.

She looked around the park. The sun had come up an hour ago but it took a while to appear over Arthur’s Seat so the Links was still draped in a dawn haze. To her left, the occasional delivery van trundled along the road, while the paths through the park carried one or two early runners or dog walkers.

Einstein was nosing around a golden retriever near Whitehouse Loan, Goldie’s owner lagging behind, an elderly man whose name Dorothy had never learned. Part of her liked the camaraderie here on the Links, but another part of her shunned the social aspect.

‘Einstein,’ she called, feeling stupid. The name had been Hannah’s idea. They already had a cat called Schrödinger, and apparently the real Schrödinger and Einstein didn’t get along, so it made sense. Einstein padded along Leamington Walk, nose to the ground as he moved back and forth. Dorothy looked beyond him to the spire of Viewforth Church, then the Meadows spreading out, and beyond that Edinburgh Castle perched over the city, the Royal Mile trailing from it like the spine of a great sleeping dragon.

This was such an incredible city to be a part of, but it was easy to forget it as you went about everyday life. In Dorothy’s case that was burying the dead and consoling the bereaved in the funeral business based in her home right behind her. But this early-morning ritual, fresh air and open space, cut grass and oak and sycamore, the incredible views, this always reminded her how lucky she was.

Einstein stopped at a tree and lifted a leg, his movement slightly clumsy because of the missing eye. Dorothy turned to the house behind her. Three floors of black brick Victorian townhouse that the Skelf family had owned for a hundred years, running a funeral business and, more recently, a private investigator’s. Dorothy thought about how her life had changed over the last couple of years, from helping husband Jim with the funeral arrangements to taking over both businesses when he died, enlisting her daughter Jenny and granddaughter Hannah to help.

She imagined Jenny in bed on the first floor. She pictured Hannah asleep in her flat with Indy ten minutes’ walk round the Meadows. This was another of her morning rituals now, imagining the city sleeping while she was awake.

She looked at the top floor of the house, the studio where her beautiful drum kit was set up, Abi asleep on the futon there, one of her teenage students who’d needed a place to crash a year ago and hadn’t left. And she thought about Archie, her right-hand man in the funeral business, at home across town, about to embark on another day of building coffins, embalming the deceased, prepping bodies for viewing, all the little things that made dealing with a dead relative or friend a tiny bit easier when they’re done right. Dorothy thought about her own grief. Just because she was an expert with other people’s, didn’t mean she knew how to handle her own.

She realised she was still holding the black bag of Einstein’s shit, so she walked to the dog-waste bin and dropped it in. She looked for the dog, saw his black-and-white tail disappear into the pine trees at the corner. On the other side was Sam’s Coffee Box, the old, converted police box, and the public toilets. Einstein was always sniffing around, sometimes breaking into a run after a squirrel, or barking at a wood pigeon in the trees. She watched the copse for a while, didn’t see any movement.

‘Einstein.’

A bus rumbled along Bruntsfield Crescent. A decorator’s van drove past and she spotted two grammatical mistakes in their slogan.

Still no movement in the trees.

‘Einstein.’

She walked towards the pines, looked at the ground underneath, moss and needles. As she got nearer she saw more clearly between the tree trunks but couldn’t see the dog.

‘Einstein.’

She pictured him when she first met him, his worried face poking from the back seat of a crashed car, sniffing at his dead owner.

She felt something in her stomach, realised how much she’d come to love the dog and his early mornings and chasing games, the way he followed Schrödinger around the house trying to ingratiate himself, only making the cat more annoyed.

She was halfway to the trees when Einstein emerged, nodding his head in time with his trotting paws.

Dorothy felt relief, then something else. The dog had something in his mouth. Had he managed to catch a squirrel after all? Maybe a baby bird fallen from a nest. She was more used to Schrödinger bringing her little dead offerings.

As Einstein got closer she saw the colour, pale pink, some red, and she swallowed hard. The dog reached her, face eager, the object clamped in his jaws.

Dorothy felt bile in her stomach again.

‘Drop it,’ she said, pointing at the ground.

Einstein looked unsure, didn’t want to give up his prize.

‘Drop,’ Dorothy said, more sternly.

Einstein lowered his head and placed the object on the grass, looked up with his one eye for praise. Dorothy crouched down and touched his head absent-mindedly. ‘Good boy.’

She scratched the dog’s ear and stared at the object. It was damaged, a lot of chewing around one end, the skin grey, but there was no doubt.

It was a human foot.

2

JENNY

Sunshine shimmered on the Water of Leith as Jenny stood at the corner of The Shore and Commercial Street. She stared at the rippling water and felt warmth on her face, screwed her eyes shut and imagined vitamin D soaking into her skin and making her healthier.

She knew this part of Leith better than she ever used to. She came here when things got on top of her, when the itch of her ex-husband became too much. It was a year since he’d escaped from prison on the way to court, abducted her then-boyfriend Liam, then Jenny herself. He would’ve killed them both if it wasn’t for Hannah. What a thing, to owe your life to your daughter.

Today, like usual, Jenny began at the Malmaison Hotel, showing staff the picture of Craig, just in case he was hanging around. It would be crazy to do that, but everything he’d done in the last two years was crazy. He was out there somewhere. He had his passport, but the authorities had no trace of it being used. Maybe he stowed away on a Norwegian tanker or worked his way on a fishing boat to God knows where, or took the train south and snuck through the Channel Tunnel. There were a million ways he could be on the other side of the planet, but that seemed too easy for him. He told Jenny they had unfinished business and she believed it, that’s why she was here.

After Malmaison she’d worked her way up the bars and restaurants, Fishers, The Shore, The Ship on the Shore. She knew all the staff now, they greeted her by name, often had a gin and tonic ready. It started as a ritual, looking for Craig here, but had grown into something else, a way for her to feel part of a tenuous community of bar and restaurant workers, a way to soak up the harbour smells and salty air.

And it was a way to release the pressure of the funeral stuff. Two years since her dad died and she’d got involved in the family business, and she still wasn’t used to it. She wasn’t as adept at dealing with grief as her mum or Hannah’s girlfriend Indy. She answered phones and took details and sorted orders of service and flowers, celebrants and venues, but it crawled under her skin and put her on edge. She had no barrier between the grief of others and her own.

And now there was this morning’s fucking foot. Her mum had walked into the kitchen while Jenny was chewing toast and held up a poo bag. It was clear from the size and weight that it wasn’t one of Einstein’s craps. So now the Skelfs were finding human feet in the park. Jenny asked why the hell she didn’t leave it there, but Dorothy had spotted a fox and worried it might make off with it. So she’d phoned her pal Thomas at the police, who gave her a bollocking for moving the foot from where it was found, then said he was on his way with a forensic type and some uniformed officers for the crime scene.

Jenny watched two gulls diving for discarded chips down the road. It wasn’t even noon yet and she’d had three gin and tonics. That was obviously a mistake but one she was embracing. She walked into The King’s Wark, the ancient pub where she’d first spoken to Liam, employed as a PI by his suspicious wife to tail him. For a while it was their place, a running joke, but Liam was now Jenny’s ex, so who’s laughing?

She didn’t recognise the barmaid, short and strong-legged, ponytail and Polish accent. She ordered a G and T and showed her Craig’s picture on her phone, got a head shake. He was a ghost out there somewhere, waiting to haunt her again.

She glugged the gin and looked around. Mostly empty except for two middle-aged women in suits at a window starting early for lunch. Jenny wondered what it would be like to go to an office every day, swap banter around the water cooler, gossip about Debbie in accounts, what Nigel had done to his hair and when was he going to come out already. The truth was she’d never been one to join in, felt like an outsider her whole life. Or maybe that was just her way of justifying being friendless and living with her mum at the age of forty-six.

The door opened, letting in traffic noise and a slash of sunshine. Despite herself, Jenny looked up and felt a thud of hope in her chest, maybe it would be Liam. Stupid, but she couldn’t help it. She ended it with him last year because she was too dangerous to be around, but had regretted that as the months wore on and Craig stayed unfound. Liam still worked at Victoria Quay, still had an art studio around the corner, so it wasn’t a crazy idea he might pop in.

But of course it wasn’t him now, it was a third smart businesswoman come to join the other two, smiles and hugs, wine poured, people just being friends in a way Jenny found hard to fathom.

She sipped her drink and thought about calling Liam, like she had a hundred times, sitting here wishing her life away. Her phone buzzed, a message from the universe. She swallowed as she pulled it out, but it was just a reminder on her calendar: McEwan Hall, 12:00pm.

Shit, she’d totally forgotten, what a crap mum. She downed her gin and headed for the door, off to watch her daughter graduate.

3

HANNAH

She felt ludicrous in a flappy black graduation gown over the dark suit she’d borrowed from Indy. Being a student, Hannah didn’t have any smart clothes, but Indy needed respectable dress for dealing with the bereaved. Hannah scratched the label at her neck, felt the weight of the olive-green hood with white fake-fur trim. So much daft tradition attached to this, though at least nobody wore those ridiculous mortarboard hats.

The McEwan Hall was fizzing with energy, hundreds of graduating students in their subject’s colours, friends and family in the circle and balcony. Hannah gazed at the ornate domed ceiling, thin light drifting through high windows, a colossal pipe organ on stage up front. Students were parading across the stage at a clip, doffed on the head with an old cap then handed scroll tubes and ushered away. She looked at the balcony and saw Jenny, Dorothy and Indy beaming at her. She was doing this for them, really, she couldn’t care less about it all.

Soon it was her turn, shuffling out of the row, up on stage, heard her name read out. She managed not to trip during her ten seconds of fame, then back to her seat. A first in physics at Edinburgh was something, but she almost didn’t make it. She struggled through her third year because of everything with her dad, but when he went to ground she made a conscious decision to sort her shit out, not to let him dictate her life. So she’d knuckled down in her final year, revelled in relativity, quantum field theory and cosmology, spent her energy studying and revising, experimenting and writing. And here she was, one of the best in her year with a fully funded PhD in the astrophysics department.

The hall reverberated with applause. Hannah realised the ceremony was over and everyone was beaming. She looked at her course mates, felt kinship but nothing more, most of them avoided her because of the business with Craig, then there was the funeral home and PI work. She was not a normal student. She tapped the scroll tube with her fingers, she might not be a normal student but she was a good one.

The bigwigs paraded off stage and out the door, an old man at the front waving a staff with an ornate silver top. Hannah saw her family standing and clapping. She threw them a warm smile and waved her degree, then went out of the door blinking in the sunshine.

Sonder was busy for a lunchtime, mostly graduates and their families. At least she wasn’t the only one in a gown and hood. She and her gran were at one side of a booth by the window, Jenny and Indy across from them. The place was mint green and grey, busy spotlit open kitchen.

Hannah looked at the menu, fancy stuff at a tenner for a starter, twenty for a main. The menu had an explanation of the restaurant’s name: ‘Sonder: The realisation that each passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own.’ She swallowed in recognition, thought about what the other three women in the booth did for a living, coming into people’s lives at a terrible moment and treating their grief as if it was the most important thing in the world. Which it was.

She looked out of the window and saw a young man draped in blankets begging at the cash machine across the road. She wondered about his vivid and complex life, the bad decisions and life blows that led him to that place. Thought about how easy it would be to end up the same. Then inevitably she thought of her dad, hiding somewhere, guilty but free.

Indy clinked her glass with a knife. Dorothy had ordered champagne, and Hannah couldn’t remember if she’d ever drunk the stuff before.

Indy was beaming. ‘I’d like to say something.’

Hannah beamed back.

‘First of all, congratulations to this wonderful woman on getting a goddamn first for her physics.’ She locked eyes with Hannah, who felt her heart swell. ‘She’s worked so hard, she deserves it. It would’ve been so easy to say “fuck it” and take a year off, but Hannah you are so strong, stronger than you know, and I’m unbelievably proud to call you my girlfriend.’

Indy took Hannah’s hand across the table and looked round. ‘To Hannah.’

Hannah’s cheeks flushed, bubbles tickling her throat as the champagne went down.

Indy removed her hand. ‘There’s something else.’

She put her glass down. She was wearing a low-cut red dress with a large floral print, like a Georgia O’Keeffe thing, and best of all it had pockets. Hannah had no idea where Indy found these things. Indy tucked her dyed-green bob behind an ear and swallowed.

‘I just said I was so proud to call you my girlfriend,’ she said. ‘But I was hoping I could call you something else.’

She slid out of the booth and took something from her pocket. She got down on one knee and opened the ring box, held it towards Hannah, who felt dizzy. The ring was platinum, a small emerald in the centre, the mount carrying an interlinked Hindu pattern. Hannah stared at it and tried to get her mind to work.

‘Hannah, would you do me the incredible honour of being my wife?’

Hannah looked at her face, shining eyes, kind smile, and her eyes welled up. She was vaguely aware of Mum and Gran smiling in the booth, but there was only one person in her universe right now.

‘Of course,’ she said, pulling Indy to her feet and kissing her.

The Meadows was bursting with life as Hannah and Indy walked arm in arm around Melville Terrace. Or maybe that was just Hannah’s state of mind, or the daytime champagne she wasn’t used to. Indy squeezed her arm and laid her head on Hannah’s shoulder, and they bounced on their heels, dumbly in love.

She smelled barbecues across the road, saw folk playing with Frisbees, footballs, the thwack of balls at the tennis courts. Magpies flitting between trees, dogs sniffing scents, squirrels clinging to tree trunks.

They reached the corner of Argyle Place and Hannah looked at their flat. There would be a million things to sort for the wedding, but she wasn’t thinking about that, just trying to soak in every moment.

Indy opened the stairwell door, turned and kissed her long and hard against the wall. She kissed back.

‘Oof,’ Indy said. ‘I love you.’

‘Likewise, babes.’

Both said with laughs in their voices.

They walked up three flights of stairs, and Indy went to unlock the door but frowned. It was ajar already. Indy pushed and it swung open. As Indy went inside Hannah saw that the wood around the lock was splintered.

‘What is it?’ Hannah said.

Indy stood in the hallway. Hannah looked past her at the large sign draped across the back wall. ‘CONGRATULATIONS’ in a colourful font, three unnecessary exclamation marks at the end, a pattern of party balloons and streamers in the background.

Hannah felt the unfamiliar ring on her finger, turned it with her other hand, imagined champagne-blood fizzing to her fingertips.

Indy turned to Hannah, shaking her head.

‘I didn’t do this,’ she said, and Hannah knew straight away what that meant.

4

JENNY

Jenny followed Dorothy into the kitchen.

‘Christ, Mum, is that the foot?’

There was a poo bag in the middle of the kitchen table the size and shape of a foot.

‘Sorry,’ Dorothy said, scooping it up by the tied handles and swinging it over to the kitchen worktop. ‘I had to put it somewhere so the dog or cat didn’t get it.’

‘There are six body fridges downstairs.’

‘All full.’ Dorothy filled the kettle at the sink and switched it on.

Jenny looked at the two giant whiteboards on one wall of their kitchen-diner, one for funerals, the other for PI cases. The funeral one was full, lots of death work. The PI one was less busy, just an ongoing missing person and a possible unfaithful husband, their bread and butter these days.

The room filled with the whoosh of the kettle as Dorothy made tea and wiped the table where the foot had been with a wet cloth.

‘Nice health and safety,’ Jenny said as she went to the window, took in the view of Bruntsfield Links. Late afternoon and the park was full, families and students, tourists getting some unexpected sun. Her dad’s ashes were scattered out there and she liked to think his spirit had soaked into the grass, although she didn’t believe in any of that. But then she thought the same thing every time she looked out of this window, wasn’t that a kind of belief? Working in funerals had made her realise that truth didn’t matter much in the face of faith. The private-investigator stuff was more about truth, but she wasn’t convinced that knowing the truth helped.

Schrödinger skulked in, avoided her as usual, then stretched out in a sliver of sunlight on an armchair. The cat still had the wiry frame and disdain of his street-cat roots. Einstein followed the cat into the room, sniffed up at the foot in a bag on the worktop, then wagged his tail at Schrödinger, who ignored him. It was pathetic, really, but they both seemed to get something out of the relationship, otherwise why do it?

‘I can’t believe my daughter is getting married,’ Jenny said, turning to her mum.

Dorothy was smiling. ‘I know, our little Hannah.’

Jenny was a long way from mushy about marriage, one failed attempt with a fucking murderer made sure of that, but Hannah and Indy were rock solid, so much stronger than anything she’d had, a fact that gave her a twinge of regret.

Dorothy placed mugs of tea on the table and sat down. ‘Do you remember how your dad used to sit her on his shoulders in the garden when she was little? Bounce up and down, trying to reach the wood pigeons in the trees. I thought it would kill him.’

She trailed off. Grief never died, it lay dormant then surprised you with painful waves at random times. Playing with his granddaughter didn’t kill him but a heart attack did.

‘She’s lucky to have Indy,’ Jenny said.

She was thrilled for Hannah, but her own marriage had failed and now she’d turned her back on a guy she might’ve had a second chance with. Dorothy’s marriage of fifty years was over, but at least she was back in the game with Thomas. Jenny had met him in the kitchen on a few early mornings recently, so he was staying over.

Dorothy sipped her tea. ‘We’re all lucky to have each other.’

A statement so obvious it didn’t need a reply, but it was good to hear the truth.

Jenny got her tea and nodded at the bag on the worktop. ‘What about the foot?’

‘Thomas got delayed, he’ll be here soon.’

‘What do you think?’

‘Nothing yet.’

‘So it’s just a human foot that turned up in the park?’

Dorothy shrugged.

Jenny sipped tea. ‘Is it male or female?’

‘I’m no expert, but I think it’s a woman’s, large though.’

Jenny stared at the bag, pictured it jumping off the counter and walking out of the house. A door banged downstairs, footsteps. Jenny imagined a second foot bounding up two stairs at a time to find its partner.

Hannah burst through the door, Indy behind, their faces tripping them.

‘Dad’s back,’ Hannah said.

Jenny swallowed and felt sick.

Dorothy straightened her shoulders. ‘What?’

Hannah told them about the break-in, the graduation sign, looked at Indy for reassurance, but it felt to Jenny like the volume had been turned down in the room, replaced by a ringing that turned into a roar. She felt suddenly hyper-aware of the dust motes falling in the strip of sunlight, the low-throb purr Schrödinger was making in his throat, the swish of Einstein’s tail on the floorboards.

‘Are you sure it was him?’ Dorothy said.

But who else would break into her flat on graduation day and put up a banner to let her know he was thinking of her, to let her know she was never safe, to throw an icy dart into her heart when she thought she was clear of him.

Hannah ran out of steam, Indy standing to the side now as if Craig’s bullshit had put distance between them.

Dorothy nodded. ‘You should move in here, just for a while. To be safe.’

Hannah turned to Jenny. ‘Mum, you haven’t said anything.’

Jenny shook her head. All her own bullshit was getting in the way, she had to make this as logical as possible. She hadn’t in the past and that was one of the reasons Craig was still out there.

‘We need to tell the police, obviously. Have you done that?’

Indy shook her head. ‘We came straight here.’

Makes sense, the Skelfs were the support network, the comfort through all this shit.

Dorothy stood up. ‘Thomas is on his way here anyway, to look at the foot.’

Hannah frowned. ‘What foot?’

Dorothy nodded at the bag on the counter just as the downstairs doorbell rang. ‘That’ll be him now.’ She picked up the bag and headed for the door.

5

DOROTHY

Thomas kissed her cheek at reception then introduced her to Emilia from forensics. Emilia was pretty, slight build, blonde ponytail, mid-thirties, and Dorothy had a flash of envy at her youth.

Dorothy took Thomas’s hand. ‘Listen, Hannah’s upstairs, she says Craig broke into her flat.’

‘Is she OK?’

‘She’s fine, just a little shaken. She wasn’t in at the time. Can you speak to her?’

‘Sure.’

Dorothy looked up the stairs, then at the bag hanging from her hand.

‘Maybe give her a few minutes to calm down, she’s not going anywhere. We should do the foot first.’

‘Is that it?’ Thomas said looking at the bag.

Dorothy nodded to the back of the building. ‘Let’s go to the embalming room.’

She led them to the separate part of the Skelf premises. Out front were lilies and oak furniture, viewing rooms and the chapel, plush carpet and boxes of tissues. Down the corridor and through the door was the business side, embalming room and body fridges, the coffin workshop and storage, gurneys corralled outside the garage where the hearse and body van were parked.

Dorothy felt the cold of the air con as she entered the embalming room, saw Archie over the body of Mrs Raven, an elderly client who passed peacefully in her sleep after a very short spell with cancer. Dorothy wished all their clients met death so benignly, but the truth was very different. So many painful, drawn out and undignified ways to go – dementia, motor neurone, Parkinson’s – it was hard not to wish for a sharp and simple end.

Archie looked up from Mrs Raven and nodded. The embalming pump was throbbing away, pushing artificial life into her veins. Mrs Raven was only five years older than Dorothy, which made her swallow.

‘Can you join us?’ Dorothy said.

Archie checked the pump gauges then met them at the other metallic body table. He was the same age as Jenny but seemed older, bald, a full but neat beard, stocky and reserved. He seemed to have coped well with his own mother dying last year. It hadn’t exacerbated his Cotard’s Syndrome, he’d been balanced and engaged thanks to the meds and Dorothy was thankful for that. He was the vital engine room of the business and she couldn’t do without him.

Dorothy put the bag on the table. It seemed too small. She glanced at the table’s drainage slats, thought about fluids draining away. She looked at the six body fridges, each with a magnetic whiteboard on the door carrying the details of the person inside. It was a business, of course, but more than that.

Emilia opened a small case and pulled on blue nitrile gloves, untied the bag and pushed the sides of it down to reveal the foot. Dorothy caught a whiff of a cheap scent, recognised it as the stuff they sprayed on the bags to hide the shit stink. There was no smell from the foot except for a slight grassy earthiness.

Emilia looked at the row of body fridges.

‘Before you say anything,’ Archie said, ‘it’s not one of ours.’

The first thing they’d done when Archie came into work was check all the bodies in the fridges, just in case. Archie had assured her it wasn’t possible, and of course he was right.

Dorothy glanced at Mrs Raven’s bare feet, smaller but wider than the one on their table. She looked back at their foot, saw that the second toe was longer than the big one. Wasn’t that supposed to mean something? It was a left foot, and Dorothy wondered for the hundredth time that day where the right one was.

Emilia picked it up, fingertips pressed against the heel and toes, and turned it over in her hands.

‘Female, size seven, I think. From the skin elasticity I’d say elderly. We can get a clearer idea after tests back at the lab.’

She ran a finger along the sole and Dorothy felt her toes cramp as the ball of her own foot twitched away from an imagined touch. She wondered if Archie felt this when he dealt with the hundreds of corpses that pass through this room.

Emilia ran another hand over the top of the foot, across the bridge towards the ankle. ‘It’s been embalmed.’

‘Interesting,’ Thomas said.

‘Is it?’ Dorothy said.

‘Well, that has implications.’

‘Like that it’s not murder.’

‘Not necessarily.’ Thomas ran a finger along his chin.

Dorothy watched him and felt a trill in her stomach. He was handsome and trim for a man in his fifties, buzz cut and salt-and-pepper beard. He had a hard-earned confidence from years being a Swedish black man in the Scottish police, but he wore that confidence lightly. She thought about his hands running along her bare arm in bed, down her side, across her bum and down her thigh. She’d asked him out for a kind-of date a year ago and they took it slow. They were both widowed, had known each other’s partners, her husband of fifty years, his wife of thirty. Those ghosts haunted them all the way, but the trick was to make peace with your ghost, don’t let it tell you who to kiss or touch or make love to. She and Thomas had been sleeping together for a few months. It began as the simple pleasure of a man touching her body, a solid presence in her bed, then more, much more. He felt like home to her now. She’d allowed herself to be loved and opened up to him. Love wasn’t grand gestures and fireworks moments, it was walking to the bakery together, sharing breakfast in the morning, lifting a stray hair from the other person’s pullover without a second thought.

‘It doesn’t make much sense if she was murdered, for her then to be embalmed,’ Emilia said.

Thomas nodded at Dorothy. ‘Finding a foot in Bruntsfield Links doesn’t make much sense.’

Dorothy smiled. ‘True.’

Forensics were out there checking, but Dorothy had already looked where Einstein emerged from the trees, there wasn’t anything there, just a small clump of trees, a coffee box and a public toilet.

Dorothy heard a rhythmic thump and crack from the top of the house and she checked her watch. Emilia looked at her, the other two had been around long enough to know.

‘It’s Abi,’ Dorothy said. ‘Practising drums. She lives with us.’

Emilia looked confused but Dorothy shrugged, it was too much to explain. The drums rumbled in the background, Abi was letting off steam.

‘Can I?’ Archie said, holding his hands out, still in his blue gloves.

Emilia checked with Thomas then handed the foot over.

Archie pushed at the bridge then the arch, separated the toes and ran his hands around the heel. ‘It’s a shit job.’

‘What?’ Emilia said.

‘It’s a terrible embalming job. If my loved one came back like this I’d ask for a refund. Not drained properly, cheap fluid, shoddy workmanship.’

Thomas narrowed his eyes. ‘Could you identify where it was done?’

Archie sucked his teeth. ‘I can ask around.’

Emilia took the foot back. ‘Obviously we’ll get a DNA sample back at the lab. Plus maybe we can get an idea of what killed her.’

Archie looked at Thomas, then Dorothy, then back at the foot.

‘Well, of course there are the bite marks.’ He reached out and touched the ragged ankle, loose flaps of skin, pale bone sticking out from the spongy flesh. ‘This looks like it’s been chewed.’

‘By what?’ Thomas said.

Dorothy shook her head. ‘I didn’t see Einstein at it.’

Archie shrugged. ‘Then it must’ve been something else.’

‘Or someone else,’ Emilia said.

6

HANNAH

It was a half-hour walk past the big houses of The Grange and Blackford then up the hill to the Royal Observatory. Hannah felt sick at the thought of her home being violated by Dad. She didn’t know when she and Indy would be able to go back, she was just lucky Gran could take them in. When would this shit ever end? And they weren’t even safe at the Skelf house, Craig knew that place well, all the women in his life huddled together in fear. No, she couldn’t think like that. She had this appointment to go to and she needed life to be normal. She was an engaged woman, for God’s sake, she should be happy.

She walked up the grassy path around the edge of Blackford Hill, surrounded by gorse and willow, bees zigzagging from one to the other, dogs trotting after scents in the undergrowth. She thought of Einstein with a foot in his mouth. What kind of crazy shit was Dorothy involved in now?

The sun beat down and Hannah had damp patches under her arms as she reached the cluster of buildings at the campus. The hexagonal green turret of the observatory towered over the spread of different-era buildings, gateposts with ornate lamps flanking the entrance. She’d been here before in her final undergrad year for courses on early cosmology and astrobiology. She turned left towards the Higgs Centre for Innovation. It was a new building, space-aged stone and glass curves, open-plan rotunda mirroring the observatory. Edinburgh Uni had capitalised on Peter Higgs winning the Nobel, building this in collaboration with businesses and renaming the theoretical physics department down the road after Higgs too.

José Ramírez was waiting for her at reception and gave her a warm handshake. He was short and solid, thick black hair and beard, standard-issue science postgrad fashion, checked shirt, worn jeans and Converse.

‘Hannah Skelf?’ he said. ‘Let me show you round.’ His Spanish accent was thick and rolling.

He was amiable as he guided her through a handful of buildings, from the futuristic Higgs site to the Victorian observatory, plus more prosaic PhD offices where she nodded and smiled at a bunch of people. This visit was a courtesy, her PhD was a done deal. Normally the astrophysics department interviewed potential candidates but she had a first-class honours, was at the university already and was already committed to joining the exoplanet research group. They used cutting-edge data from NASA’s Kepler missions to categorise planets found around other stars, defining their characteristics to establish which were earthlike. It was a growing field with thousands of new planets, and there was even an open-sourced crowd-science project, NASA had freed up tons of data for people to search on their own.

José was talking about that now, the Planet Hunters TESS project.

‘It stands for Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite,’ he said, lisping his sibilants.

He was hunched forward at the café table, playing with his empty disposable cup.

‘I’ve detected eight possible planets myself already,’ he said.

The view out of the window behind him was distracting, a wide stretch of Blackford Hill, grassy moorland crisscrossed with dog-walking paths, then beyond that the Braids and the foot of the Pentlands. It was like there was no city at all.

‘So that’s in your spare time,’ Hannah said.

‘I know, it’s geeky,’ he said. ‘To have a hobby so similar to our work here.’

‘I think it’s cool.’

He smiled. ‘Then you’ll fit right in.’

She was used to the dorky undercurrent of physics, and it got dorkier as you got deeper in, but she embraced that.

‘I think I will.’

It was nice to sit and talk about exoplanets, not think about Dad.

José picked at the edge of his cup, placing little shards in a neat pile. ‘So you’re definitely going to take the offer?’

Hannah imagined sitting here every day, taking a break from number-crunching, from trying to find planets out there where life could exist, life that could be just like us or so utterly different we couldn’t get our heads around it. She thought of all the different kinds of intelligence on earth we couldn’t communicate with – dolphins, ants, trees – a billion flora and fauna that were still a mystery to humans. How could we hope to talk to life out in the universe? But we had to try, the trying was the thing.

She realised she hadn’t answered. ‘Yes, I am.’

José nodded, picked more pieces off his cup, placed them on the table. His smile faded and he dropped his head. ‘I have something to ask you.’

Hannah waited. Gulls hung in the wind outside and she imagined being out there with them, the breeze on her face, the buttery smell of the gorse.

‘You are a Skelf, like the funeral people?’

Hannah smiled and nodded. They got funeral work all sorts of ways, but mostly word of mouth.

José lifted his head and held her gaze. ‘And a private investigator?’

Hannah was still getting used to that, even after a couple of years of finding out people’s secrets. ‘That’s right.’

‘Maybe I have a case for you? Is that how you say it, a case?’

Hannah looked at him. He had typical Spanish charm, open and friendly in a way that seemed natural. He had hazel eyes, thick fingers, a fine haze of hair on the back of his hands.

‘What kind of case?’ she said.

He nodded and looked around, like he was checking no one could overhear.

‘I think someone is … the word is “gaslighting” me.’

Hannah was surprised, gaslighting a white man in his twenties? ‘How do you mean?’

José looked sheepish. ‘I have been getting messages.’

‘What kind of messages?’

José shook his head. ‘I don’t want to say details until you take the case.’

‘What do the messages say?’

‘I’m not sure.’

Hannah touched her ear. ‘I don’t understand.’

José swallowed and seemed to decide something. ‘The messages seem to be from … out there.’ He raised his chin and indicated out of the window.

Hannah didn’t say anything.

José looked down at his hands. His cup was decimated now, just a pile of stacked pieces. ‘Like, not from earth.’

Oh boy. An astrophysics postgrad who thought he was being gaslighted by aliens. Hannah pressed her lips together.

José ran a hand through his hair. ‘I know, I know. I don’t believe the messages, I know they cannot be real.’

‘So what do you want me to do?’

‘I want you to prove they’re fake,’ José said. ‘I want you to find out who is messing with me. Whoever it is, they know what they’re doing.’

‘Who would do such a thing?’ Hannah said.

‘That’s what I want to know,’ José said. ‘Will you take the case?’

Hannah looked out of the window, the gulls were gone. She thought about her dad out there, sending her messages to wind her up. Never letting her settle.

‘I’ll take it,’ she said.

7

JENNY

When Jenny thought of Cramond she pictured the tidal island, the boat club, waterside properties, summer walks with ice cream. But Cramond Vale was none of that. Jenny drove the van down the street of blocky sixties houses and stubby brown tenements with poky windows. She parked outside number twenty-three, went up and rang the bell.

Sophia answered with a rice cake in her fist. Her blonde hair was tied back in a tight pony, giving her an air of primness. Jenny tried to remember how old Hannah’s half-sister was now, eight? She wore a burgundy polo shirt with a school logo on the chest, an ancient sailing boat.

‘Hi, do you remember me?’ Jenny said.

Jenny spent some time with Fiona a year ago when it kicked off with their mutual ex. That was in Fiona and Craig’s old place, an expensive Stockbridge townhouse. Now Fiona and Sophia were living with Fiona’s mum, Sophia bounced out of private school.

Sophia nodded and chewed her rice cake. ‘You made Mum cry.’

‘That’s not strictly true.’ Jenny wanted to say that Sophia’s dad made her mum cry. ‘Is she in?’

Sophia nodded behind her. ‘Through the back.’

The girl disappeared into a side room and picked up her phone. Did eight-year-olds have phones now? Jenny went to the kitchen where Fiona was sitting at a small folding table with a laptop and a glass of Rioja, half-empty bottle alongside. She was smaller than Jenny in every dimension, slim, short, compact, like a pocket-sized version. They were the same age but Fiona had always looked after herself more, but it was a year since they met face to face and there was something ragged about Fiona’s edges, like she’d never recovered. Fiona had the same high pony, sharp features, smart outfit, but there was an air of tension, or maybe Jenny was just projecting.

Jenny tapped a knuckle on the open door. ‘Hi.’

Fiona looked up, nodded to a vacant chair, resignation on her face. ‘So he’s resurfaced.’

Jenny had spoken to her on the phone, talked through Hannah’s thing at the flat. She sat down as Fiona took another wine glass from a cupboard, filled it and slid it over. The table was cheap seventies wood covered in ring marks.

‘We think so,’ Jenny said.

Fiona cleared her throat and took a drink. ‘What do the police think?’

‘They haven’t really looked into it yet,’ Jenny said. ‘They checked over the house, but they don’t have the manpower for more.’

Fiona nodded, looked around the kitchen. ‘This place got broken into a few years ago. Mum was asleep upstairs. They took all the electronics, cash, car key. Broke the glass in the back door.’ Fiona looked at the door to the small garden. ‘The police did fuck all. The crime-prevention officer told her to get an alarm and security light, build a higher fence, make the place less of a target than next door.’

Jenny nodded and sipped wine. Fiona looked around as if imagining a burglar creeping through the house, helping himself.

‘You’re sure it was Craig?’

‘Who else would break into Hannah’s place on graduation day and put up a congratulations banner?’

Fiona shrugged. ‘An obsessed student or lecturer?’

Jenny bit her lip. ‘Hannah couldn’t think of anyone.’

‘But it could be.’

‘It’s possible. But you know Craig, it was him.’

Fiona took a drink. ‘Yeah, it was fucking him.’ She shook her head. ‘I stupidly thought he might leave us alone. Might just disappear, live a quiet life somewhere.’

‘That’s not really his style.’

‘No.’

They both had daughters by the man, both knew him too well. They’d been taken in by his charm, his confidence, his way of making you feel like the most important woman in the world.

Fiona pointed at her laptop. ‘This was so obvious, I can’t believe I never thought of it.’

Jenny shook her head. ‘We didn’t know for sure he was still around, did we? He could’ve gone to Thailand or Venezuela.’

‘He’s still here.’ Fiona looked out of the window again at the seven-foot fence at the bottom of the garden, vertical wooden slats, razor wire across the top.

‘He has this address,’ Fiona said, waving a hand around. ‘He knows where you live too.’

Jenny thought of the Skelf house, a beacon on the edge of Bruntsfield Links. Come and get me, it said, come find the Skelfs and fuck us up.

‘Exactly.’

Fiona tapped the laptop screen. ‘So you think one of our former clients is helping him?’

Jenny shrugged. ‘We know he’s been living in or close to Edinburgh for a year undetected. How is that possible? I routinely check hostels and homeless shelters, nothing. His credit cards haven’t been used and his bank balance is untouched. He has to be getting help from someone. He must be able to get food and stay warm. How can he do that?’

Fiona sucked some more Rioja down. She’d always been a daytime drinker but this seemed more than that. Sophia came in, took a packet of rice cakes from a cupboard and left.

‘How’s she coping?’ Jenny said.

‘They’re so resilient. She missed her pals at the academy to begin with, but she’s made new friends at Cramond. I still haven’t told her the truth about him. But I did tell her he was never coming back, and it looks like he’s made a fucking liar of me again.’

‘We’re not to blame here.’

Fiona waved her hands in the air. ‘I know, it’s him, not us, blah, blah, blah, but fucking hell it feels shit.’

‘It does.’

Silence in the kitchen, sparrows chirping in a tree outside, sunshine lancing through the branches onto the grass.

Fiona swivelled the laptop to face Jenny, and she saw a spreadsheet full of names and numbers.

‘I’ve got a few candidates,’ Fiona said. ‘Three of our former clients who liked Craig a lot, who might be arsehole enough to help him out despite everything. They each have the resources to help him stay invisible.’

She finished her wine with a flourish, clunked the glass on the table and stabbed a finger at the laptop screen. ‘Let’s go ask them.’

8

DOROTHY

She was the oldest person in Sneaky Pete’s by forty years. It was a tiny dive venue on Cowgate full of kids and, Dorothy was glad to see, a large percentage of young women, no doubt because of the bill. The audience were dressed the same as indie kids through the ages, DIY jackets and tops, mismatched trousers and bright boots.

Dorothy sipped her whisky and looked round. It wasn’t much bigger than her kitchen, scruffy bar to one side with beautiful hipster bar staff. She was between an exposed brick pillar and the mixing desk, which was just a tattooed woman with a laptop on a stand. Two walls were covered in black-and-white murals, one saying ‘Dance Yrself Clean’ in huge letters, which Dorothy was pleased she recognised as an LCD Soundsystem song title. Having young drum students pass through her house for the last forty years had some advantages, she was a million times more up to date with music than others her age.