7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

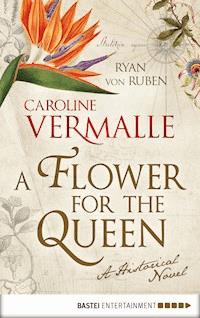

- Herausgeber: Bastei Lübbe

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

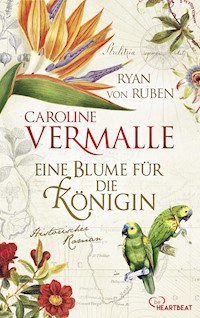

England, 1770. Young gardener Francis Masson is asked by the King to search for a rare orange blossom in South Africa. As his ship departs, Masson has no idea that he’s about to embark on the adventure of a lifetime. During his hunt for the mysterious flower, he doesn’t anticipate the untamed nature of the African continent, nor the subtle scheming of competing plant hunters. As he makes the acquaintance of eccentric botanist Carl Thunberg and his elegant accompaniment, Masson's fate once again takes an unexpected turn ...

A lively adventure novel set against the vibrant backdrop of the South African countryside

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 437

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

About this book

Title page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Epilogue

Afterword

England, 1770. Young gardener Francis Masson is asked by the King to search for a rare orange blossom in South Africa. As his ship departs, Mason has no idea that he’s about to embark on the adventure of a lifetime. During his hunt for the mysterious flower, he doesn’t anticipate the untamed nature of the African continent, nor the subtle scheming of competing plant hunters. As he makes the acquaintance of eccentric botanist Carl Thunberg and his elegant accompaniment, Masson’s fate once again takes an unexpected turn …

A lively adventure novel set against the vibrant backdrop of the South African countryside.

Caroline VermalleRyan von Ruben

A FLOWERFOR THEQUEEN

A Historical Novel

BASTEI ENTERTAINMENT

Digital original edition

Bastei Entertainment is an imprint of Bastei Lübbe AG

Copyright © 2014 by Bastei Lübbe AG, Schanzenstraße 6-20, 51063 Cologne, Germany

Written by Carolin Vermalle / Ryan van Ruben

Edited by Victoria Pepe

Project management: Steven Hensel

Cover design: Jeannine Schmelzer with illustrations © getty-images/DEA/G. CIGOLINI; © shutterstock: Sergey Mikhaylov | Rtimages | Hein Nouwens

E-book production: Urban SatzKonzept, Düsseldorf

ISBN 978-3-8387-5805-3

www.bastei-entertainment.com

FOR HEATHERAND RUSSEL

CHAPTER 1

CANADA, 21 NOVEMBER, 1805

“If I write one more obituary, I swear it will be the death of me,” said Jack Grant, the corners of his young, purple-lipped mouth turned downwards in a petulant frown.

The travelling coach and its team of horses rumbled and snorted in reply to the coachman’s whip, ripping a tear through the bleached silence of a November morning on the road from Montréalto Pointe-Claire.

The coachman, sunk down in his greatcoat, watched the road for potholes and signs of ice whilst his two passengers buried themselves in their blankets and mufflers, the interior of the coach offering scant protection from the Canadian winter outside.

Jack gazed across at his father, trying to measure his mood and wondering just how far he could press his point.

“All those lives filled with accomplishment! I cannot help but feel how short my own obituary will be unless I get started on something more worthwhile. I need a column, father.”

The older man did not react and continued reading from the documents that lay on his lap, pausing only to make careful, unhurried calculations with a stub of pencil in the margins of each page.

Finally, just as Jack began to think that perhaps his father had not heard, George Grant removed his spectacles, pinched the bridge of his nose and looked across at his son. He found it remarkable how little they resembled each other. George was short, stocky and as thick through the chest as he was broad across the shoulders. The parts of his face that were visible above an expansive but neatly trimmed beard looked to have been pounded and hammered into place on life’s forge. Jack, by contrast, was tall and thin and had a face that could have been cut from the most delicate crystal, as yet untarnished by even a hint of worry or facial hair. Whilst his father could occupy a space in almost complete stillness, Jack was constantly fidgeting, checking his lapel or straightening a cuff. As he examined his son, George couldn’t help but observe that everything about his son crackled with impatience.

“We have been through this before, Jack,” said George, “You need to experience the world before you can judge it. One has to crawl before one can—”

“But what experience is there to be gained by listing out the deeds of the dead? I need something that I can get my teeth into, something serious!” interrupted Jack.

“—walk,” continued George in a weary tone, ignoring the interruption. “Besides, there are not many things more serious than providing fitting epitaphs to those who have passed. It is fine, meaningful work, Jack.”

“Meaningful?” Jack almost choked on the word, “Day after day I reduce entire lives to a few lines, most of which nobody will even bother to read. Where’s the meaning in that? But with a column I would be free to give all those heroic acts the space and consideration they deserve.”

“Life is about more than great acts and heroic deeds, Jack.” A sudden jolt brought an end to the war of words between father and son and lifted both men out of their seats. Boxes of oranges and luggage stowed in the racks above fell about and onto them.

“What was that?” asked Jack, shaken.

George Grant rapped on the roof of the carriage, interrupting a string of muffled curses coming from the coachman’s seat, “Smithers!”

The coachman heaved on the reins and brought the team to a stop before jumping down from his seat. “A man on the road, sir. He threw himself in front of the horses, he did!”

“There!” cried Jack, turning in his seat to point out the rear window. A few yards back, at the side of the road, a phantom silhouette staggered and then fell from view, erased by the mist.

“Are the horses all right?” asked George Grant.

“Right enough to get us home, sir.”

“Well, then. Let’s get going. We’re already tardy, and Mrs Grant won’t be best pleased as it is.”

“Are we not going to help him?” protested Jack.

“Don’t be foolish, Jack. For all we know, he could be a highwayman. Besides, the weather is getting worse.” George Grant took a last look back into the mist before pronouncing his final words on the matter. “Let’s go.”

But before the coachman could release the brake, Jack had wrenched open the door and was clambering down onto the icy sludge.

“Highwaymen don’t throw themselves under horses. He’s clearly lost, more than likely injured, and now you’re going to condemn him to death!” He looked defiantly up at his father and then turned and marched back up the road to where the figure had vanished.

The two men left behind watched as Jack headed off into the mist and snow. “The ice storm will be fast upon us, sir,” Smithers said flatly. Without speaking, George looked up at the sky before letting out a heavy sigh and then freed the rifle from its mounting at the back of the carriage and climbed down onto the snow.

Jack had left the road and was trudging through knee-high snow, the hem of his greatcoat already sodden and dragging along behind him. He cried out with all the authority his nineteen years could muster:

“You, sir, are you injured?”

But the phantom had disappeared, swallowed by the cold and mist. The whinnying of the horses, impatient now that they had a nose for home, carried across the snow. It was the only sound to be heard above the rising hum of the north-east wind. Jack paused briefly to catch his breath and then continued on a ways down the side of the road, his enthusiasm waning with each crunching footfall. Suddenly, he halted.

George came up alongside and cast his eyes over what had given Jack cause to stop: drops of blood scattered across the snow.

George nodded to Jack, urging him on. Faced with real evidence of the stranger and with his own blood now cooled by the rising wind, Jack’s confident bluster had given way to fear and uncertainty. He hesitated.

George set his jaw in silent disapproval as he pushed past his son, following after the red and grey footsteps that led further from the road and into the tree line.

As they plunged on, all manner of strange objects began to appear, littering the snow: hessian bags, kid-leather pouches, wooden boxes of all sizes, scissors, a small spade and what looked to be a miniature spyglass fixed to some sort of brass contraption. Strangest of all was a rusty birdcage containing bright yellow flowers, each with four tendril-like petals.

The hum of the wind dropped for a moment and in its place a shallow rasping sound could be heard coming from a depression a few feet away. George Grant cocked his rifle, allowing the sound to carry before moving on. And then they saw him.

In a shallow ditch lay an old man. His cloak and dress suggested some degree of wealth, but even though they were wet with snow and blood, it was clear that their sheen was long gone. The elbows of his coat were patched and the wooden heels of his boots worn away. His breath escaped in short, wispy bursts.

“Sir, are you all right?” asked George, scanning the surrounds before looking back to the old man.

But save for the painful rasp of his breathing, the old man made no other sound. His fingertips, white with the onset of frostbite, were clasped around several worn, leather-bound journals held together by a strap secured with a lockable clasp.

“We should ride for help –”

“He doesn’t have that long.” This time Jack did not protest at being contradicted. “Here,” George said, taking charge, “take the rifle, and bring his things.” George lifted the old man over his shoulder with ease and made his way back to the carriage. Jack followed behind, gathering up the stranger’s possessions along the way.

“Smithers!” cried George as they neared the coach.

The coachman, barely hearing his name above the now gusting wind, engaged the break of the coach before jumping down to open the carriage door.

Once the old man was laid down across Jack’s seat, George removed the wet and blood-stained cloak and wrapped him in one of the blankets. With the old man installed, Jack then struggled onto the coach.

As pellets of frozen rain began to pelt the roof, the coach lurched forward and then gathered speed, the sound of the whip inaudible above the wind that now drove them towards home.

CHAPTER 2

At two storeys, the Grant house was large but not overbearing. With its shingle roof, whitewashed clapboard exterior and white-painted window frames, it was a decent if unexceptional example of the Georgian style that was favoured by the wealthy traders and merchants who chose to live in the rural surrounds of Montréal.

Inside, fires crackled in all the rooms. The warm tones of polished wooden tables, oak floorboards, flock wallpapers and upholstered chairs could not have been more different from the frozen, monochromatic landscape outside its windows.

Servants rushed with measured haste, sweeping, dusting and arranging anything that was not fixed down. At the centre of the bustle, Mary Grant moved like the eye of the storm, leaving not chaos and destruction in her wake, but order and a healthy dose of “just so”.

She was dressed in a midnight-blue housedress, her dark hair held in place under a starched bonnet that sheltered features that had once been fine and delicate, but which were now weathered by the long Canadian winters. If the youthful beauty that had encouraged so many eyes to look upon her had been lost, it had been subtly replaced by a forceful personality that was no less commanding.

“This storm had better not last much longer, or else our guests will be forced to stay at home,” she declared to no one in particular. Mary glanced out of the dining-room window while she carefully rolled out the antique lace runner. Then, turning to her son, she said, “Not the right time to play good Samaritan, Jack. Not the right time at all.”

“When is the right time then, Mother?” asked Jack, amused, as he stood warming himself by the fire.

“Anytime but the annual Parish Ladies Committee dinner!” countered Mary before looking back to her table and inspecting the shine on the silver..

“That’s the spirit,” remarked Jack wryly.

“George! George! Did you find out who he is?” Mary asked her husband as he struggled up the stairs from the basement kitchen holding a battered box of oranges.

“It’s all right, no need to worry,” he said, looking first at Mary and then pointedly at Jack. “He isn’t a highwayman. He’s been bandaged up and is by the fire. Jack, why don’t you leave your mother in peace and go sit with him?”

“No need,” said Jack. “Grandmother is there.”

“Oh, go on, Jack,” said Mary, pre-empting another battle between father and son. “You are no use to me here, and on your way you can take in some tea. It may help him to get his strength back.”

“Fine,” replied Jack.

“Interesting lesson here for you, Jack,” said George, gently laying a hand on his son’s shoulder as he passed by.

“Oh, and what would that be?” asked Jack, his voice thick.

“Consequences.”

Jack shrugged off his father’s hand and strode out of the room, his head tucked into his shoulders like a cork in a bottle, stopping up the frustration that was bursting to be let out.

Mary continued to adjust the place settings, carefully measuring the distance between the silverware. Without looking up she asked, “How seriously is he hurt?”

George paused, carefully weighing up his reply. “I know how much this evening means to you, but the old boy has had a bad knock and the weather is absolutely foul. You’ll find a way to manage, you always do.” He lifted an orange out of its box and held it out across the table as a peace offering.

Mary crossed her arms, her voice hardening. “I’m sorry too, George, but foul weather or not, we are expecting eight for dinner, four of whom will be staying overnight, and that doesn’t even allow for staff. There just isn’t room. He must be gone before this evening.”

“Very well.” George sighed and put the orange back in the box. After all this time, he should have known better. It would take more than a piece of fruit, even if it had cost him a small fortune, to placate Mary Grant.

“I am serious, George, call the doctor out and pay for a room at the inn if needs be, but he can’t—”

“Yes, dear,” George replied wearily. “He will be gone by this evening. I give you my word.”

CHAPTER 3

The irregular shadows cast by the flames of the fire played across the low ceiling of the summer kitchen. A boxy, single-storey side extension to the main house, it consisted of a rectangular room with a plain, pine floor, and unadorned, whitewashed walls. The three sash windows on two sides, which allowed cross breezes to cool the room in summer, were now closed tight against the cold outside, and the gaps between the sashes and their frames stuffed with rough cloth.

The summer kitchen had been brought into service to help with the preparations for the dinner and to accommodate the servants of those guests who were due to remain overnight. It was also ideally suited as an ad-hoc infirmary: with both the brick oven and the open hearth blazing, it was warm and yet far enough out of the way that the household could continue with its preparations for the evening’s events with only the minimum of disruption.

Bundled in blankets and with a bandage around his head, the old man was installed in front of the hearth on a rocking chair, turned towards the flames, drawing in their warmth like a fading flower turned to the sun. His face was possessed of deep furrows on his brow and a mouth that turned down slightly at the corners. Combined with the crows’ feet that spread from his eyes to his ears, the map of lines on his face suggested a life that had amassed equal time in the contemplation of serious thoughts as it had in the expression of joy, although the latter being communicated mainly through the eyes rather than the entire face. As he held his palms out to the fire, he flexed elegantly shaped fingers that were stained a light yellow at the fingertips from too many years spent handling tanner’s bark. His eyes were light green, as if washed out by years of exposure to the sun, and they darted cautiously from the fire to the figure that sat silently in a corner of the room.

On a stiff, high-backed chair, her face concealed beneath the shadow of her bonnet, an elderly woman sat embroidering beneath one of the windows.

“Good afternoon,” the old man said by way of greeting. But the woman seemed not to have heard. Without looking up, she remained focused instead on the work before her, her fingers nimbly avoiding the point of the needle that trailed a bright orange silken thread.

“Grandmamma is not deaf, she just doesn’t have anything left to say,” said Robert Grant, Jack’s nine-year old brother, who sat on his knees next to the fire, his hands clasped together in his lap. “That’s what mother tells us, anyway. Is it true that you were nearly dead but my brother saved you?” he asked, changing the subject as he inspected the array of objects that Jack had placed neatly on the floor beside the old man.

“Oh, yes,” said the old man, pulling his gaze away from the old woman and turning to the boy with a look of genuine embarrassment. “Your brother saved an old fool from himself. What a courageous young man … and your father. Oh, what an inconvenience my being here must be for your family.”

The old woman did not contradict him or raise her gaze from her needlework when he tried to get up. However, the rocking chair, layers of blankets and his lack of strength all conspired against him, forcing him to give in and let his bandaged head rest on the high back of the chair, the exertion leading to a fit of coughing.

“Young man, would it be too much to ask … my cloak …”

Robert obliged and, springing up from the floor, fetched the cloak from a stand next to the hearth where it had been hung to dry. The old man felt the lining nervously with his sore, red hands but failed to find what he was looking for.

“Hmm,” his tired gaze shifted from the coat to the floor around his chair. “I seem to have lost my spectacles. No matter. Have you seen a leather journal — I had it with me, but it also seems to …” A trace of panic entered his voice as he squinted first at the objects on the floor and then around the room.

Without hesitation, Robert made for a ragged canvas tote placed at the foot of the old man’s chair and retrieved the assemblage of leather-bound notebooks. “Is this what you were looking for? My father said you were holding it when they found you and that you wouldn’t let go.”

The old man reached under the blanket and produced a small key upon a chain. He inserted the key into a brass catch, releasing the clasp that secured the contents of the bundle. With the catch undone, it was clear that what at first had appeared to be several journals tied loosely together was, in fact, a single tome. In addition to the leather strap, the leather covers of the journals were stitched together, and the slight discrepancies in sizes, types of paper and signs of wear suggested that the collection had been built up incrementally over time.

The old man opened the journal from the back and after leafing through the last pages, which were entirely blank, he flipped towards the beginning of the journal, through the musty and wrinkled pages revealing highly detailed, annotated anatomical drawings of plants and flowers, each one a representation of a theoretically perfect specimen.

Robert leaned forward to get a better look, but at the same time keeping his feet planted at a respectful distance “I can read books that don’t have pictures in them, you know.”

A smile creased the old man’s wrinkled face when, upon stopping almost exactly halfway through the first book in the assembly, Robert saw that there was a page missing and that on the facing page next to the torn remnant, instead of a drawing, there was only a rust coloured watermark staining the page in the rough outline of a bird.

“What’s that?” asked Robert.

“Please don’t let my brother disturb you, sir,” said Jack, without looking up from where he had been preparing the tea on the sideboard against the wall furthest away from the fireplace. “How are you feeling? Do you have all your things?” Jack placed a tray down on a large bench table at the centre of the room and began pouring tea into the first of several porcelain cups.

“Oh, everything seems to be in order, thank you.”

“Robert, be a good lad and give this to Grandmamma.” At Jack’s request, Robert reluctantly did as he was told. The old lady did not touch her tea, but continued her needlework, as if lost in the detail of the pattern that was beginning to emerge within the frame.

“Can I offer you some tea or a biscuit, perhaps?” asked Jack as he began to pour more tea into a battered tin cup that he retrieved from a hook on the wall.

“Thank you, that would be most welcome,” replied the old man. “I’m afraid that we haven’t been properly introduced. My name is Francis Masson, and I am forever indebted to you, sir.” He tried again to rise to his feet to shake Jack’s hand, but the effort proved too much and he sank back into the chair with an apologetic smile.

The old lady’s cup and saucer clattered to the floor. Robert rushed across to help, picking up the pieces of broken chinaware as Jack did his best to ignore the commotion. “Jack Grant. It’s a pleasure to meet you, Mr Masson.” In place of a handshake, Jack handed the tea to the old man, who wrapped his hands around the cup, drawing as much warmth from it as he could. “Are you all right, Grandmother?” Jack asked in a slow and deliberate tone.

But she appeared not to have heard, and after Robert had wiped the spilled tea with a tow-cloth rag, Jack returned his gaze to the old man. “If you don’t mind my asking, Mr Masson, what were you doing out on this godforsaken road in the middle of such weather?”

“God did not forsake it, since He put your good self on my path, Mr Grant.” The old man closed his eyes as he brought the cup up to his nose and gently inhaled its scent. “I was looking for flowers, witch hazel to be precise.” He then sipped his tea carefully, his eyes still closed. “Oh, that is delicious. Ceylon, is it not?”

“I’m sorry, I don’t really know much about tea, Mr Masson, I’m more of a coffee man, myself.” Jack watched as the old man drank from the cup, each time closing his eyes and inhaling deeply before taking a sip, which he then swallowed carefully and deliberately.

“Well, your family must be worried about you, mustn’t they?” continued Jack. “The storm is just about over now. Smithers will drive you home when it is safe. Where do you live?”

“My family? Oh no, I … I live alone. I was due to sail for England, but the ship was delayed when the weather turned, and so I thought I would make one last foray.”

Just then, shafts of winter sunlight poured through the south-facing windows, signalling the end of the storm. The garden had been transformed into a world of crystals and stalactites, sparkling in the timid sun. Even the strongest of trees sagged under the weight of the ice that encased their leafless limbs.

“This ice storm. It’s quite something, isn’t it?” asked the old man. “It’s the first time I’ve seen one. This climate, though, the cold … I fear it is something I will never get used to.”

“Are you not from around here?”

“From England, well, originally I’m Scottish but His Majesty the King sent me here a few years ago.”

“Really?” asked Jack, the surprise in his voice making plain his scepticism. “In what capacity, may I ask?”

“I am, I was … his gardener. I suppose you could say that I came here to hunt. They are such elusive things, flowers, and this cold is much worse than I expected. I had become so used to the heat …” his voice trailed off as he slipped into reverie.

“My knowledge of geography is not what it ought to be,” said Jack, his patience beginning to wane, “But I don’t recall England having a particularly hot climate, and Scotland even less so.”

“Quite right.” Mr Masson drained the last of his tea. “But you see, I did most of my collecting in Africa.”

“Africa?” cried Robert, his eyes shining. “Did you see lions? Did you get to kill one?”

“Really, Robert!” Jack scoffed.

“It was very nearly the lion that killed me!” exclaimed the old man. “Please trust me when I tell you, young sir, that facing a lion is not something I would like to experience ever again.”

“Can you believe it, Jack?” cried Robert. Jack could not. “How big was it? How did you kill it? Did you use a gun or a spear?” Robert jumped up and ran around the room holding an imaginary rifle and making shooting noises.

“Now, Robert,” interrupted Jack, turning towards his brother and adopting the same stance and tone of voice he had seen his father use so many times before. “I am sure Mr Masson is too worn out to tell stories. Leave him be.”

“It’s is no trouble at all, Mr Grant, really,” the old man reassured him, before turning to Robert and saying in a hushed, conspiratorial tone, “In Africa, there were hippopotamuses too. Do you know what they are? Hippopotamus amphibius …”

With Robert’s mouth agape as the old man began to embark on a detailed description of the quadruped, Jack left the summer kitchen and walked through the reception room, across the main hall and then into the dining room, where he found his mother placing the final touches to a table set for the feast. She allowed herself a small, satisfied smile as she stepped back to admire her handiwork.

“Nice table, mother. I would say your best one yet.”

“Thank you, Jack. I thought you were looking after your guest?”

“Well, if you fancy hearing tall tales about lions and hippopotamuses, then be my guest. I am sure that Mr Francis Masson, servant to the King of England no less, would be only too pleased to oblige.” Jack looked beseechingly at his mother and pleaded, “I’ve done as you asked and looked after him, but I think I have had about as much as I can bear. Where’s Smithers? Is he ready to go yet?”

“You can’t send him out now, Jack. With all that ice on the road, it’s not safe.” George Grant said as he ambled in wearing a smoking jacket, whilst still perusing his ledger. “Besides, all this talk of lions sounds like just the thing for our readers at the Gazette. Maybe you can get the story out of him before our guests arrive, what do you think? You did say that you were tired of writing obituaries.”

“Fanciful tales of fantastic beasts was not exactly what I had in mind,” Jack retorted.

“Really, Jack, I am sure you are exaggerating,” Mary Grant said. “Lions, here in Canada? The poor man must really have had a knock. Perhaps I should see for myself.” She passed her eye over the table one last time and then made off in the direction of the summer kitchen, with Jack dragging his heels close behind.

***

Despite the mayhem of the afternoon, Mary could not help but smile at the sight that greeted her in the cheery warmth of the summer kitchen: Robert, wide-eyed and transfixed, sat atop an old wooden chest that he had dragged over, while the old man, with his worn leather book on his lap, had shrugged off his blanket and was describing incredible scenes with an energy and animation that belied his feeble condition. Mary hovered at the door, keeping out of sight and not wanting to break the spell.

“… and when you think they’re taking a bath, beware, they run underwater as fast as on land! Oh, and there was the time with the poison arrows … But wait, I must start with the beginning. Let’s see. It was in 1772. Good grief, is that really thirty-three years ago already? It is, isn’t it? How quickly time passes.”

Masson had not heard them come in and Jack joined his mother at the doorway and theatrically stifled a yawn. With a silent nod and a frown, she gestured for him to re-join, which he did, reluctantly.

Satisfied that the old man was not about to run stark raving mad through the house, upsetting all her careful preparations, Mary cast a final eye over the room before discreetly backing out and closing the door behind her.

Masson looked up at the sound of the door shutting and then across to the old woman, who still seemed in a world of her own. After only the briefest of pauses, he turned to Robert and, with a sad smile, began his tale.

“It was a hot summer’s day in London — I remember it like it was yesterday — and when I think that it all started because of a mistake.”

CHAPTER 4

MAY 1772, LONDON

There was no escape from the sun as it bore down mercilessly on Ian Boulton and James Simmons. The two men stood and waited at the end of Crane Court, a small cul-de-sac off Fleet Street that was home to the Royal Society. In front of the men was a small trestle table, which had been placed to one side of the main entrance so as not to impede the comings and goings of the Society’s illustrious members. Fixed onto the cast iron railings behind them was a small sign with the words “Botanical Expedition” carefully stencilled in black.

“Bad traffic for sure,” said Simmons, squinting at the sun from under his three-cornered hat. “They’ll come.”

“It is twenty-five minutes past ten already,” complained Boulton, as he snapped back the cover of his watch before putting it in to his pocket and pulling out a handkerchief. “Didn’t you say ten o’clock at the south door? Show me the advertisement again.” He pulled at the starched stock around his neck and wiped at his brow, being careful not to skew his wig as he examined the broadsheet that Simmons was hastily spreading over the table. The words had been ringed in pencil and as Boulton re-read it for the seventh time that morning he could not imagine how they could have made it any clearer that all applicants were to present themselves at the south door of the Royal Society no later than ten o’clock on the morning of the first of May. The advertisement ended with the words, “No submissions will be accepted beyond this date and time. All enquiries are to be addressed to Mr Boulton, secretary to Sir Joseph Banks.”

Boulton huffed in frustration as he finished reading. “But is it obvious that this is the south door?” he asked, worry creeping into his voice. “Perhaps you should have put up a bigger sign.”

“The sign is as per your instructions, sir, and if I may be so bold as to suggest that a gentleman proving incapable of locating the south door may, by definition, be unworthy for consideration. After all, if one is applying for the post of botanicalexplorer,then surely one should know one’s north from one’s south?” Simmons grinned at his own joke as he refolded the newspaper.

“And may I suggest to you, Simmons, that being in the post of my assistant, your function is to assist. You can be assured that should we return empty-handed, Sir Joseph will prove perfectly capable of showing us the door, and it will matter not one jot whether it is the south or the north one!”

In the distance, the Bow Bells sounded half past the hour. Boulton muttered an oath and watched helplessly as the pedestrians going about their business on Fleet Street all walked past the entrance to Crane Court without showing any interest whatsoever. His brow patting increased to a frenzy, threatening to dismount his wig entirely.

“Well, that’s that, Simmons. You don’t happen to have a relative with the requisite qualifications, do you?” Boulton asked, his tone almost hysterical.

“I’m afraid my lot are all gone to the colonies, sir. My wife’s family, however,” he snorted derisively, “showed remarkable navigational skills in finding their way into my house, but now seem unable to find their way out.”

Boulton stared down at his diminutive assistant, unable to understand how the wretched man could so brazenly fail to appreciate the seriousness of the predicament that they now faced. “Well, what do you propose I tell him? Hmm? And then there’s the Admiralty. And the King. Oh dear God.” Boulton was now sweating so profusely and in such a state of agitation that Simmons could not be sure whether it was perspiration or tears that cascaded down his cheeks.

“Hold on a minute, sir,” Simmons looked passed Boulton and to an approaching figure. “We may not be out of luck just yet.”

Boulton followed Simmons’ gaze and saw a man turn the corner into Crane Court from Fleet Street carrying a battered wooden container the size of a hatbox.

His eyes were verdant sparkles, at odds with the serious and unsmiling face in which they were set. He was not younger than thirty years of age and was strongly built, but he pulled and fidgeted at his clothes. Although they were neat and clean, they seemed to sit uncomfortably upon him, as if they were new or were seldom worn. He was clean-shaven, but his hair was long, bleached a lighter shade of brown by the same sun that had tanned his skin, and it had been hurriedly tied back into a ponytail. On top of his head was a three-cornered hat which, unlike the rest of his ensemble, was battered and worn.

He was tall and walked with his chest thrust out, but not in a way that was pompous or aggressive. His upright gait only implied a sense of certainty of purpose and direction that, when combined with his size and build, sent out a subtle message to others that it might be better to step aside rather than to block his path or hinder his progress.

But Boulton was in no mood for subtleties. He grabbed Simmons by the elbow and rushed straight towards the man who saw the pair coming and, sensing a confrontation, instinctively pulled the box towards his chest with his left arm in order to free his other.

He veered to the right so as to avoid them, but they changed course to match him and just as a collision seemed inevitable, Boulton beamed his most convincing smile and opened both arms expansively, effectively blocking the pavement. “We thought you would never come! Please do hurry, Sir Joseph is waiting.”

The man let the case drop to his side and replied with the faintest of Lowland lilts, “Sir Joseph Banks? Waiting for me?”

“Indeed,” said Boulton hurriedly, his smile widening to almost impossible proportions. “He’s with the Admiralty right now, deciding who will go on the expedition. We must hurry.”

“I’m afraid you’re mistaken,” the man said firmly. “I'm here to deliver seeds and a sample of Paeonia albiflora.” Boulton looked to Simmons, who simply shrugged.

“From China?” he said holding up the box by way of explanation. “They are for Mr Solander from Mr Aiton.”

“Seeds?” asked Boulton, caught between confusion and disappointment.

“Yes, seeds. My name is Francis Masson. I’m an under-gardener at the service of His Majesty the King at his gardens at Kew.”

“Seeds,” Boulton repeated emptily. “So … not an explorer, then.” His eyes started to lose focus.

But a smile had started to spread across Simmons’ feral face. “Did you say a gardener, sir?”

“Under-gardener, actually, I—” began Masson.

But Simmons cut him off, an edge of excitement creeping into his voice. “With, I am sure, an excellent knowledge of flowers?”

Simmons glanced sideways at Boulton, who started to nod enthusiastically. Simmons then reached up and, although barely able to place both hands on Masson’s broad shoulders, he looked the taller man square in the eye before asking, “Mr Masson, sir, you’re in good health, I trust?” He gave the man a firm slap on the shoulder as if to check.

“Well, yes,” Masson said, trying to shrug out of the smaller man’s surprisingly firm grasp. “But I’m afraid that I am late already, and Mr Aiton would be most displeased—”

“You know your north from your south?”

“Of course, but if you will just step aside,” replied Masson, beginning to lose patience.

“Then you, sir, are just the man we need! Isn’t that so, Mr Boulton?”

Boulton looked Masson up and then turned back to Simmons. A smile slowly replaced his frown and surprised by the certainty he suddenly felt, he could only utter a single word in reply:

“Absolutely.”

CHAPTER 5

With no time left to lose, Simmons and Bolton frogmarched a still-protesting Masson through the front door and down panelled corridors that smelled of tobacco and old books.

Sir Christopher Wren, Samuel Pepys, the Earl of Halifax, Isaac Newton — not a smile amongst the bunch of them as they peered mirthlessly down from beneath flowing wigs, captured for posterity on canvases that lined the walls of the corridors along which the three men now raced. Through the efforts of these men, the Society had claimed a place at the forefront of the enlightened world and as Masson was dragged beneath their eminent gazes, he couldn’t help but feel that the only emotion their unblinking stares conveyed was one of undisguised disdain.

But Boulton was in no mood for giving sightseeing tours or for appeasing the spirits of deceased fellows. Neither was he too concerned by the Society members who were still alive but were either too slow or too preoccupied with ruminations of greatness to mind their backs so that they were pushed aside as the trio scrambled to get to Sir Joseph’s rooms on the second floor.

“Flowers are the new gold, Mr Masson,” Boulton wheezed as his silver buckled shoes thumped up the solid oak treads. “Scientists want to study them, merchants want to trade them and no stately home can be considered complete without its own collection of exotics. We need bold men to search out these treasures, and Sir Joseph will reward you handsomely for your brave decision to volunteer.”

At the top of the stairs, Boulton tried, with the little breath he had left in his lungs, to prepare Masson for his interview. “Now, just remember,” he wheezed, “Sir Joseph is a man just like the rest of us. He breathes the same air and is as fond of a joke as the next man. So just answer whatever questions he has for you, and as long as you don’t ramble, stutter or hesitate, you will be fine. There is absolutely no need what so ever to be nervous. Is that clear, Mr MacMasterton?”

“It’s Masson, sir, Francis Masson,” corrected Simmons as Boulton wrapped twice on the large oak-panelled door.

Upon hearing a single, bellowed “Come!” from the other side of the door, Boulton pulled down on his waistcoat, loosened the stock around his neck and, with a silent appeal to the heavens, opened the double doors.

“No, wait,” whispered Masson, urgently trying to grab at Boulton’s arm, but it was too late.

They walked into a large, well-lit office. The sash windows were open on both sides, allowing what little breeze there was to cool the space. To prevent the numerous stacks of documents arrayed around the room from being scattered, fossilised crustacea, stuffed animals, multi-coloured crystals and many other strange and wonderful objects had been brought into service as paperweights.

At the centre of the room was Sir Joseph Banks: naturalist, explorer, knight of the realm and, at just thirty years of age, a legend in his own time.

Masson had heard how, upon meeting a person of great stature, people were often disappointed or surprised that the person was not as large in life as the reputation that preceded them. To Masson, however, Banks did not disappoint.

When Banks discovered that the HMS Endeavour would make a journey around the world to observe the path of Venus, he leveraged the full weight of his inherited fortune and family connections to obtain a place on the boat. When the First Lord of the Admiralty blocked his requests, he bypassed the navy and gained approval for his participation from the government instead. He also contributed to the expedition a sum more than double that provided by the King and one hundred times greater than the annual salary of the ship’s captain, James Cook.

Cook, who now stood slightly behind Banks, had the look of someone who was enjoying a comic play but could not laugh out loud. He was almost two decades older than Banks and was dressed in the uniform of a captain of the Royal Navy.

It might have been Cook who commanded the ship on a circumnavigation of the globe that lasted three-years, but on their triumphant return the previous summer, it was Banks who managed to steer a course through the fickle waters of public opinion and lay claim to the title of hero of the expedition.

Banks had taken with him the eminent botanist Daniel Solander, and together they found and brought back over three thousand plant specimens, most of which had never been formally described. Banks’s success had propelled England to the head of the botanical establishment, greatly increasing the importance of the gardens at Kew as well as adding enormously to the work done there. Although William Aiton was officially the director of the gardens, it was an open secret that Banks had made use of his newly formed friendship with the King to transform Kew from a King’s pleasure garden into a botanical repository. If it hadn’t been for Banks, Masson would very likely still be pruning box hedges rather than helping to catalogue the most diverse botanical collection in the world.

Whilst tall and of the same age, where Masson’s looks were unrefined and rough, Banks was remarkably handsome. Where Masson’s class and upbringing had taught him a reflex for deference, Banks deferred to no one, least of all Lord Sandwich, who stood opposite him. The corpulent First Lord of the Admiralty, who constantly dabbed at his forehead and upper lip with a silk handkerchief, was poured over the numerous technical drawings and plans that lay spread out on the desk between them.

Boulton cleared his throat. “My Lord, Sir Joseph, Captain Cook, may I intro—”

“Ah, Mr Boulton!” interrupted Banks. “Just in time! This must be our man.” Banks squared up from behind the table, addressing Masson directly. “Tell me, sir, do you travel light?”

Masson looked searchingly at Boulton for an answer, but the rotund assistant simply closed his eyes and continued to perspire.

“Well?” repeated Banks. “If you were to go on a rather long and arduous sea voyage, would you pack, you know, sparingly?” A wry smile had creased across Cook’s face, but the old Lord was either deaf or did not deign to react, choosing instead to continue poring over the documents before him.

“I … I suppose I would endeavour to, sir, yes,” answered Masson.

“Splendid!” roared Banks, so loudly that the old Lord next to him flinched.

So, not deaf then, thought Masson.

“Congratulations, the job is yours!” roared Banks before continuing in a voice thick with exaggerated ceremony. “Through this thorough examination, you have officially met the exceedingly taxing criteria for selection as set out by the Admiralty Board.”

The Old Lord had put down his magnifying glass with a pained look as Cook cupped his chin in his hand, visibly struggling to contain his laughter.

“On the basis of your ability to travel with the minimum of luggage,” Banks continued, “and on this basis only, you will now take part in this crucial and monumental voyage of discovery, sailing with Captain Cook to the Cape of Good Hope. You will then, at no small expense to myself, spend a few years in the Dutch colony at Cape Town, exploring wild and as yet unmapped territory. You will identify and collect thousands of plant species never before seen by science, in the process increasing the splendour and importance of our King’s Botanical Garden at Kew. In addition to helping to make us the envy of the world’s scientific community, your work will almost certainly help to secure new revenues for the Crown at a time when they are so clearly needed.”

“Excuse me, sir, but did you say the Cape of Good Hope?” Masson asked when Banks paused for breath, an edge of panic creeping into in his voice.

“That is quite enough, Sir Joseph,” blurted the old Lord, his practised look of annoyance beginning to make way for something much darker.

“Mr Boulton, no doubt,” continued Banks, ignoring both Masson and Lord Sandwich, “will have chosen you for your profound knowledge of the natural sciences, the excellence of your craft as a botanist and your proven record in foreign exploration. Such are the standards upon which I am willing to rest my reputation.” Masson looked to Boulton once again, trying to gain confirmation that this was some kind of practical joke. But all he saw was that Boulton appeared on the verge of fainting.

“For the Admiralty Board, however, all this pales into insignificance in comparison to this most extraordinary of talents, and which, in their vaulted estimation, I have found to be so wanting: the ability to travel light!”

“Really, Sir Joseph,” the old Lord huffed, picking up from where he was cut off. “This is an Admiralty expedition undertaken at considerable expense to the Crown and no small amount of risk. You were always our first choice as leader, particularly given your past success, but we simply cannot afford you. We are prepared to make the necessary modifications to the ship’s layout to allow for a reasonable amount of space for tools, equipment and personnel, but not when it requires the building of an additional upper deck!”

“If we are to bring back the world, we cannot bring it back in the carpenter’s storeroom, my Lord. But then I suppose you would need to be a man of science to understand,” Banks replied witheringly.

“A ‘personal orchestra comprising four musicians with room for luggage and instruments’,” Lord Sandwich began to read out loud from one of the documents on the desk. “‘Stowage and provisions for a dozen hunting hounds’?”

He paused, and then flung the paper onto the table. “It does not take a man of science to see that you do not wish to bring back the world so much as to take the world with you!”

“The ship did almost capsize in sea trials, Joseph,” Cook interjected in a kind and patient tone.

“And how many times did we almost capsize in the middle of the ocean on the Endeavour?” Banks shot back, sounding proud of the achievement and indignant at the same time.

“Yes, but that was in the middle of a typhoon over one of the deepest oceans on earth, not on a fine summer’s day in a gentle breeze, cruising the Thames at low tide.”

“You know the expedition is plagued with enough problems as it is,” Lord Sandwich continued in a voice that suggested the end of the matter was fast approaching. “Let’s just hope we will be able to leave next month as planned. I am sure that Mr Forster and his son will do a splendid job in your absence.”

Banks gave a last exasperated sigh in defeat as Lord Sandwich remained implacable.

“None the less, in recognition of your service and assistance so far, I am more than happy to provide passage to the Cape for …?” Lord Sandwich’s question hung in mid-air as he regarded Masson for the first time.

“Francis Masson, at your service, my Lord,” Masson replied, still stunned.

“Exactly. Well, I believe my business here is finished, and so I bid you all a good day. Sir Joseph, Captain Cook.” Lord Sandwich picked up his cane and hat and left.

Beaten, Banks walked to the window and waited, leaving the rest of the men to fidget in silence until, at last, Lord Sandwich’s carriage moved out of Crane Court before turning onto Fleet Street, the clattering of horses hooves and the sounds of the coachman’s encouragements clearly audible in the sullen quiet that had befallen the room. From the look on Bank’s face, Masson wondered if he wasn’t willing the carriage to explode and as desperate as Masson was to set the record straight, he judged that this would not be the right moment.

“Mr Boulton,” Banks said at last, redirecting his fury to his portly assistant, “Would you care to enlighten me as to the criteria by which you selected Mr Masson?”

“By elimination, sir.”

“Clearly. But on what basis did you eliminate the others?”

“On the basis that they failed to find their way to the interview, sir.” Boulton’s face had turned the same colour as his stock. Banks’s only visible reaction was a single raised eyebrow; Cook could only chuckle and shake his head.

Banks turned and walked over to examine Masson, as if trying to assign him to an appropriate scientific taxonomy. After circling twice, he looked Masson square in the face and asked, “Can you dissect a plant and collect its seeds?”

“If I may speak, sir,” Masson started, before pausing as Boulton coughed urgently. Masson turned to see a look of blind panic on Boulton’s face, and his resolve faltered. When he turned back, he found Banks looking at him expectantly.

“I can, sir.”

“Are you familiar with the methods of Linnaeus?”

“I am, sir.”

“Have you travelled a great deal?”

“Would that be within the British Isles or beyond, sir?”

“Beyond, naturally.”

“Not a great deal, sir. In fact, not at all.”

“Not at all …” Banks repeated, turning from Masson to Bolton, who braced himself for a verbal onslaught.

The room fell silent as Banks took a deep breath and then slowly exhaled.

“Were you really that much more experienced when you stepped aboard the Endeavour, Joseph?” asked Cook, interrupting the inquisition.

“No, I suppose not,” said Banks, relenting, as he turned to his friend and smiled at the memory.

“Very well, Mr Masson. It seems that you have had the good fortune to apply for a position that no one else wants, and so, in the absence of any suitable alternative, you will go.”

Boulton sighed with relief and cast his eyes heavenwards in silent gratitude and Simmons, who had positioned himself behind Boulton’s back in order to shield himself from any impending disaster, smiled broadly and gave Masson a sincere thumbs-up.

“But, sir,” Masson protested.