7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

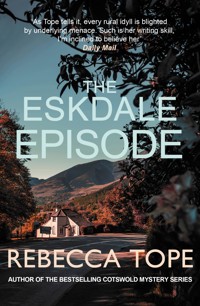

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Cotswold Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

Thea Osborne and her loyal spaniel Hepzie are still pursuing their occupation as house-sitters, despite the disastrous incidents of the past. At the moment they are staying in the late Greta Simmonds' house, which is currently between ownership. But when a body is discovered in a nearby field, Thea finds herself embroiled in a murder investigation once again. After befriending undertaker Drew Slocombe, she soon finds she's aligned herself with the police's only suspect. Believing him to be innocent, Thea works together with Drew to clear his name, although it slowly dawns on them that in a village simmering with secrets, a means and a motive could be laid at anybody's door.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 424

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

A Grave in the Cotswolds

REBECCA TOPE

Allison & Busby Limited

13 Charlotte Mews

London W1T 4EJ

www.allisonandbusby.com

Copyright © 2010 by REBECCA TOPE

First published in hardback by Allison & Busby Ltd in 2010.

This ebook edition first published in 2010.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Digital conversion by Pindar NZ.

All characters and events in this publication other than those clearly in the public domain are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent buyer.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-7490-0935-9

Available from

ALLISON & BUSBY

In the Cotswold series

A Cotswold Killing

A Cotswold Ordeal

Death in the Cotswolds

A Cotswold Mystery

Blood in the Cotswolds

Slaughter in the Cotswolds

Fear in the Cotswolds

Deception in the Cotswolds

Other titles

The Sting of Death

A Market for Murder

Grave Concerns

REBECCA TOPE lives on a smallholding in Herefordshire, with a full complement of livestock, but manages to travel the world and enjoy civilisation from time to time as well. Most of her varied experiences and activities find their way into her books, sooner or later. Her own cocker spaniel, Beulah, is the model for Hepzibah, but is unfortunately ageing much more rapidly.

www.rebeccatope.com

For Judy Buck-Glenn

in gratitude for your interest and encouragement

Author’s Note

As in all the other Cotswolds titles, the setting is in a real village. But as before, the actual buildings and people in the story are imaginary. Furthermore, the personnel on the Gloucestershire County Council have been wholly invented for the purposes of this fiction. Drew Slocombe’s Somerset home, however, is in an invented village, surrounded by other invented places, making the interface between real and imagined impossible to follow on a map.

Chapter One

The roads grew increasingly narrow and undulating, the closer I got to the village of Broad Campden. The strange intimacy of travelling with a dead woman in the back of the car joined with the timeless effect of the towering trees and long stone walls, the combination making me quite light-headed. I found myself muttering out loud, addressing my silent passenger in none-too-friendly terms.

‘What a place to bring me,’ I accused her. ‘Why couldn’t we have stayed in Somerset and done the business there?’ I groped once again for the map beside me, checking that I really did have to take the right turn shortly before the town of Chipping Campden. Yes – right, and then right again after passing through a small village, and then left into a small sloping field on the edge of a wood. Three cars awaited me, and I greeted their occupants with due dignity, straightening my tie. It was windy, the trees tossing loudly overhead.

Broad Campden was a mile or two away from Chipping Campden, in the middle of the Cotswolds. It was a region I hardly knew at all, the road map on the passenger seat a vital part of my equipment as I transported the dead woman in her cardboard coffin to her place of rest. Cardboard had been selected after an exhaustive discussion about the coffin, a year before. ‘Willow,’ she had said, to begin with. ‘I hear there are lovely willow coffins available.’

‘There are,’ I had agreed, ‘but they’re extremely expensive.’

When I told her the price, she gulped. ‘And that’s with only a modest mark-up,’ I added. She had not questioned my integrity; it was my own sensitivity to the practices of some undertakers that led to my saying what I did.

I really had not expected to be handling Greta Simmonds’ funeral so soon. She had seemed to be in good health when I met her, and I had wondered why she was so intent on arranging and paying for her own funeral at the relatively tender age of sixty. Childless, retired, and passionately committed to all things Green, she was a type that I recognised. We had got along well, and I was sorry when her family contacted me to say she had died.

The funeral had come at a bad moment, and I was in no mood for the task that particular week. It was going to take all my most conscientious efforts to conduct things as they should be conducted, for a number of reasons. It was sixty miles from home, for one thing, and poor Karen, my wife, wasn’t happy about being left on her own with our children. I took no pleasure from driving, and had little anticipation of a warm reception from the family. The dead woman had been emphatic about wanting me to dispose of her body according to sound ecological principles, while admitting that her relatives were unlikely to be very cooperative about it. I had been visited by her sister and nephew, who had stiffly agreed to the day and time for the burial, casting their eyes to the ceiling and sighing heavily as they did so. Now they were gathered, along with another nephew and a handful of friends, in the windy little field, where Mrs Greta Simmonds was to be interred.

The great majority of the funerals I conducted were in the land at the side of my house in Somerset. I had been running Peaceful Repose Natural Burials with my partner, Maggs Cooper, for nearly five years, building a quiet reputation for reliability, sensitivity and frankness. I told people how they could reduce costs, how they were still permitted under the law to opt for a range of alternative burials, and I invited them to take control of the process as much as they wished. As a result, Maggs and I earned an embarrassingly small income, but made a lot of friends.

Greta Simmonds had been unusual in several ways: her insistence on the precise position of her grave, in this obscure corner of the Cotswolds; her comparatively early age; her wry acceptance of the need for a minimum depth for the grave in order to safeguard her from scavengers. ‘You know,’ she had said, with a little tilt of her head, ‘I’m not sure I would mind if some hungry vixen took part of me home for her cubs. What’s the difference between that and providing nourishment for a lot of fat pink worms?’

I had been careful to retreat from that line of conversation. People were almost never as sanguine about their own dying as they might appear on the surface. I had diverted her to the question of timing. ‘Statistically,’ I said, ‘you are quite likely to live another thirty-five years. You need to be sure that your money is safe, and the funeral costs secured, however far in the future it might be.’

Her smile suggested that she knew something I didn’t. ‘I don’t think we need worry about that,’ she said. ‘We don’t make old bones in this family.’

As any undertaker would, I had inwardly permitted myself to hope she was at least more right than I was. With risibly low interest rates, and every prospect of rising costs and changes in regulation, the sooner I could gain access to her cash the better. But I squashed the thought. I liked this woman far too much to wish an early death on her.

She had paid for it all, up front, quite content to trust me with her money, thrusting the carefully drawn-up agreement into a large shoulder bag.

That had been fifteen months earlier and now she was dead. I was shocked when her sister, Judith Talbot, telephoned me with the news, and harassed by the implications. Maggs had been on holiday at the time, with Den, her husband. They’d gone to Syria, of all places, and I had a nagging worry that I might never see them again. I had to arrange the Cotswold burial for the day after they came back, dropping everything into Maggs’s lap only hours after she crawled off an overnight flight from Damascus. But we both knew this was the way it went. She made no complaint, helping me to slide Mrs Simmonds’ coffin into the back of the vehicle and waving me off with a good grace.

To our disappointment, natural burials hadn’t caught on as well as I’d hoped when Karen, Maggs and I began the business. If anything, it had gone backwards – we’d had fewer customers over the past twelve months than in the year we started. It was galling in a number of ways, not least financial. If it weren’t for the compensation package we got when Karen was shot, we’d have had to wind everything up and do something else. Even the stalwart Maggs’s meagre salary would have been unaffordable.

All of which meant, of course, that I was in no position to turn away work, even if I had not been obligated by my agreement with Mrs Simmonds. Maggs assured me she could watch out for Karen, as well as keeping everything going in the office. She’d done it plenty of times before, after all. And I could do the funeral on my own, since three somewhat reluctant pall-bearers had been dragooned into helping out when it came to the actual burial. It was a far cry from the days when I worked for a mainstream undertaker, with no fewer than five members of staff always in attendance.

The dead woman’s two nephews and brother-in-law helped me to carry her to the grave in a corner of a field that she told me had been hers for decades. I had, with some difficulty, arranged for the necessary digging to be performed that morning, by a man from Blockley, who still dug graves for some local undertakers. He had promised to return as soon as the funeral was over, to fill it in again. I deftly arranged the pulley ropes around the coffin, and we lowered it in without mishap. There was no vicar or other officiant. Mrs Talbot, sister of the deceased, produced a sheet of paper and read a poem by Sylvia Plath which Mrs Simmonds herself had chosen. I hadn’t heard it before, and forgot it as soon as it was over – but it was a relief not to have to endure the ubiquitous lines by Henry Scott Holland which claim that the person in the grave isn’t really dead, but just in the next room. That had never worked for me.

I was unsure of Mrs Talbot. She showed very little sign of distress at the loss of the person she must have known for her entire life, longer than anybody else, in fact. She stood straight-backed and British, reading the poem with no trace of a regional accent, wearing a well-cut dark-blue suit and expensive shoes. Her elder son, Charles, kept close, flicking frequent glances her way, as if needing to follow her lead. Mr Talbot was silent, detached, as if wondering quite why he was there at all.

And then a little surprise sent ripples through the modest assembly. The younger son, still in his teens, cleared his throat, and moved a few inches closer to the open grave. ‘Auntie Greta,’ he began, looking directly down at the coffin, ‘I’ve got a message from Carrie for you. She says she wishes she could have been here, and she’s going to miss you a lot. We both are. You’ve been the best auntie anybody could ever have. You were the bravest, funniest, cleverest person in our whole family…’ here he glanced defiantly at his parents and brother, ‘and it’s a bastard that you went and died, when we still need you. But you’ve got what you always wanted, and that’s a good thing. Rest in peace.’ He choked out the last words, and retreated to the edge of the group, turning his back on us all.

A long silence followed. I waited for the mother to go to her unhappy boy, in vain. The father was equally unresponsive. I almost went to give him a hug myself, but resisted. After a minute or so, a small woman I had not managed to place in the general scheme of things strolled calmly to the lad and laid a hand lightly on his arm. I couldn’t see the look they exchanged, but it seemed to be right.

The funeral was over. I filled in the minimal paperwork required by the law. Mrs Talbot – Judith – came up to me, looking relieved. ‘Thank you, Mr Slocombe,’ she said formally. ‘I think we’ve satisfied my sister’s wishes, haven’t we?’ As I had seen before, when she and Charles had come to my office, there was irritation lurking just below the surface. She had actually said, on that occasion, ‘When my mother died, we had a cremation. For myself, I think that’s by far the most sensible option. But I’m afraid Greta hated it. That’s why we’ve got all this carry-on now.’

‘It’s what she wanted, Mum,’ Charles had said, more than once. Until the funeral I had not met the husband or the younger son. Nor the two middle-aged couples whose names I didn’t know, and who seemed to find the whole experience altogether fascinating. One wife kept nudging her husband and whispering. Nor did I know the pretty woman who had gone to console Jeremy Talbot. Throughout the burial, she had hung back, giving the impression she thought she ought not to be there.

The wind blew fiercely from the east, and I hoped I wouldn’t have a long wait for the gravedigger to arrive, it being unthinkable to leave an open grave unattended. To my relief, I glimpsed a man in heavy boots, leaning on the gate, when we began to straggle back to our cars. He was with two young people, who I took to be idle onlookers, curious as to what was taking place in this quiet corner. Having checked with Mrs Talbot that there was nothing more she required of me, I approached the gravedigger, exchanged a few words, and paid him in cash.

Behind me a voice spoke. ‘Er…would it be OK if I helped?’ he said.

I turned to see that Mrs Simmonds’ younger nephew was addressing the gravedigger. ‘It’d be good if I could see her covered up,’ he continued. ‘And my brother, if he wants to.’

The gravedigger nodded understanding. ‘There’s a spare spade in the van,’ he said easily, as if this was no new experience. He gave me a quick wink, full of a wisdom and tolerance that made me think he would be exactly the companion young Jeremy needed.

I had some doubt as to whether Charles Talbot would be similarly moved to assist in the filling of the grave, though. He had not looked to me like a man who could abide to get his hands dirty. Then I wondered how Jeremy would get away, if he stayed behind while his family all departed. My little flock of mourners still felt like my responsibility while any of them remained in the vicinity of the grave.

‘How are you getting home?’ I asked Jeremy.

‘On the bike,’ he said, as if this was obvious. He indicated a blue racing bicycle, leaning against an oak tree, on the verge outside the field gate.

I smiled, and waved him a final farewell, turning to go straight home again. And I would have done, if it hadn’t been for the small woman standing slightly apart from the others, watching my face so intently. I smiled, pleased to have a chance to learn more about her.

‘That was very…different,’ she said, holding out a hand. ‘I’m Thea Osborne. I was looking after Mrs Simmonds’ house when she died. I feel sort of involved, although I’m not really.’

I took her hand self-consciously. People were not always comfortable shaking hands with an undertaker. They expected something bloodless, perhaps faintly redolent of formaldehyde. Thea Osborne did not appear to have any qualms. ‘Did you not know her at all?’ I asked.

‘No, not really. I only met her once, when she gave me my instructions about the house. Then she went off to Somerset and died.’ She shook her head ruefully. ‘That’s never happened to me before.’ She spoke as if a lot of other things had happened, and this was something new to add to a collection. Here, I thought, was a woman who had seen things that many others had not. A woman like Maggs, who could confront the truth without flinching. A rare creature. Then she added an extraordinary remark: ‘At least she wasn’t murdered.’

I laughed. ‘Why – do you often encounter people who’ve been murdered?’

‘Actually, yes. It happens rather often. Partly because my…um…former boyfriend, I suppose you’d call him, is in the police. So are my daughter and my brother-in-law. And there’s something about house-sitting that skews the balance of the status quo.’

‘Oh?’

‘I mean…it creates opportunities, leaves a vacuum, changes the pattern in a community.’ She shook her head. ‘I’m not really as fey as that sounds. And it might not even be true. Every murder has its own set of motives, after all.’

‘Well,’ I echoed her own words, ‘at least Mrs Simmonds wasn’t murdered. It wasn’t even much of a coincidence that she’d prearranged her funeral with me, and then died twenty-five miles from my house. She was visiting her former home, apparently. I assume those are friends of hers, from the place she lived before she came back here.’ I tilted my head discreetly towards the two couples who had been amongst the mourners. They were looking back at the new grave, quietly talking.

‘No, they’re locals,’ Thea told me. ‘But I agree it’s a very thin turnout. I’m glad I came.’

‘There’s not usually a crowd at these natural burials,’ I said. ‘They tend to be rather discreet.’

‘So you knew her?’ she said.

‘No better than you. She came into my office a year and a bit ago, and made arrangements to be buried here, where she lived as a child. I didn’t realise it was now her full-time home.’

‘She inherited it ten or fifteen years ago, apparently, when her mother died, and let it out for a while. That was when she was in some kind of cooperative place in Somerset. Which I suppose you knew.’

‘They call it co-housing. Horrible word.’

‘Indeed. Odd, don’t you think, that she left it? People generally expect to stay for ever when they join something like that.’

‘Ructions,’ I shrugged. ‘It can’t be easy to get along together in that sort of set-up.’

‘Well, she seemed nice enough. Unusual. Interesting.’

We were scattering stray comments back and forth, the wind making us uncomfortable. Skirts were whipping around female legs, which I suspected would normally be encased in trousers of some kind. ‘After all, not many people plan their own funeral when they’re only sixty – especially not a funeral like this.’

‘I had the impression of someone rather, well, forceful. I made some joke, if I remember rightly, about her living another thirty years or more.’

‘She seemed quite healthy to me,’ Thea agreed. ‘But perhaps she wasn’t. Perhaps she knew this was likely to happen.’

‘According to the certificate, she died of an occlusion.’

Thea Osborne blinked. ‘I don’t know what that is.’

‘A blockage, basically. Generally impossible to predict. Very quick.’

‘Oh. So she approached you because she wanted a woodland burial, and fixed up all the details – is that right? That weird coffin, for a start. Don’t you have to make some special application to use something like that?’

I smiled. ‘Actually no, hardly at all. You don’t really want to know the whole story, do you?’

‘Not if you can’t be bothered to tell me.’

She meant it literally – not in a nasty way, but giving me permission to save my breath, if that’s what I preferred. I saw her looking around at the people in the field. She had the air of a person slowly coming to understand that her role was over, the last line delivered, and all that remained was to leave.

The Talbots had begun to get into their somewhat elderly BMW, apart from the boy nephew who was hanging back as if wanting time alone. I wondered fleetingly about his bike and where he would go on it. The family lived miles away, somewhere the far side of Oxford. Was he intending to cycle the whole way? I watched the family for a moment. ‘Who’s Carrie – do you know?’ I asked Thea.

‘What?’

‘The boy said something about Carrie, in his little speech.’

‘Must be a girlfriend, I suppose.’

‘And why isn’t she here?’

She looked at me with a parody of patient understanding. ‘I don’t know,’ she said.

‘Sorry. I wasn’t really asking you. Just wondering. It’s funny the way families get to you, in this business. You want to figure all the relationships out, and understand the patterns. Loose ends niggle at me.’

‘I know what you mean,’ she said. ‘I’m the same, but in my case, it’s just idle curiosity. I really should get myself a life, one of these days.’

I had no answer for that, other than a string of inappropriate questions that I would have liked to ask her. Like, was she married? Where did she live? Why was she doing house-sitting, of all things? Instead, I stuck firmly to the matter in hand. ‘Is there a get-together somewhere?’ I asked, thinking I would have heard if this was the case. Mourners were moving off slowly, apparently with nowhere definite to go. Nobody had said anything about adjournment to a local hostelry, or glanced at watches as if due somewhere.

‘Doesn’t look like it. How sad.’

It was time for me to go. The melancholy little funeral had given me scant satisfaction – the woman had died too soon, with only the teenaged nephew showing any sense of loss. Every death should be important; the survivors should acknowledge that the pattern had changed. The permanent hole left by the deceased should be given its due recognition. In this case, I sensed surprised relief amongst the relatives, except for Jeremy, and an almost careless reaction from the middle-aged couples in attendance, who were purportedly local friends. Nowhere could I see evidence that Greta Simmonds’ death caused much more than a momentary pain to most of the people who knew her.

‘Oh, look!’ said Thea suddenly, as I started to walk away from her.

I turned, following her pointing finger to a tree that stood at the edge of the field. Four big magpies were lined up along a bare branch, staring down at the grave.

‘Four means a parcel or something like that,’ said Thea.

‘Pardon?’

‘“One for a wish, two for a kiss. Three for a letter, four better.” I always thought that meant a parcel.’

I smiled at her naïvety. Magpies were scavengers, and already they had detected the presence of decomposing flesh. I tried to catch the eye of the gravedigger, who would be well aware of the need to proceed quickly with his duties. ‘Maybe somebody’s going to win the lottery,’ I said carelessly.

I walked to the gate, where my vehicle was parked on a wide grass verge. I still sometimes called it a hearse in my own mind, but in reality it was a large estate car, with the rear seats removable to leave space for a coffin. Standing beside it was the young couple who had been chatting to the gravedigger, the woman sideways to me, the man behind her with a hand resting on her shoulder. She was light-skinned, in her early twenties. He was tall and black and a few years older. They were talking about my car.

‘Is this your motor?’ asked the man, unsmilingly.

I admitted ownership readily enough.

‘Are you aware that three of the tyres are illegal, and the road tax expired over two weeks ago?’ asked the girl.

They weren’t in uniform. It did not occur to me that they were police officers, so I laughed. ‘The disc’s in the post,’ I said easily. ‘And the MOT is due next week. I’ll sort it all out then.’

‘Not good enough, I’m afraid, sir,’ said the man. ‘Might I see your licence and insurance documents?’

The penny dropped. ‘Good Lord, are you police?’ I asked.

‘That’s right, sir. PC Jessica Osborne, and Detective Sergeant Paul Middleman.’

‘Osborne?’ I had automatically filed away the name of the small woman I had been chatting to at the graveside. It’s a habit with undertakers – people’s names acquire considerable importance in my line of work.

‘Right.’ The girl gave me no encouragement.

‘There’s a lady called Osborne over there,’ I continued, pointing into the field.

‘She’s my mother,’ said PC Jessica.

Chapter Two

Thea Osborne argued strenuously on my behalf, but her daughter stood her ground. ‘I do not believe the law says he can’t drive home,’ said Thea. ‘That’s idiotic.’

The girl sighed melodramatically. ‘If he lived just a few miles away, it would be different. But no way can I let him go sixty miles on those tyres. They’re bald, Mum. They could cause a serious accident.’

Both women looked at me, with very different expressions: the mother with exasperated sympathy, and the daughter with officious scorn. There was little similarity between them anyway – Jessica stood three or four inches above Thea, and was nowhere near as pretty. I was still wrestling with the fact that Thea was old enough to be the mother of this strapping PC – she must have been twelve when she had her, I thought. Or maybe she was a stepmother, or adopted the girl as an older child, when she was still in her twenties.

I repeated my feeble defence. ‘I knew they were a bit dodgy, but I was waiting for the MOT. I haven’t had them all that long. I thought they must have a bit of life left in them.’

‘And the tax?’ queried Jessica.

‘I applied for it on the computer, four days ago. It’ll arrive on Monday, I expect.’

‘You were two weeks late applying, then?’

‘I suppose so. They give you a fortnight’s leeway, don’t they?’

She rolled her eyes. ‘Mr Slocombe, sir, that is a complete myth. Besides, today is the sixteenth of March. Your tax ran out on the twenty-eighth of February. By any reckoning, you are overdue. As well as that, the usual procedure is to have the MOT test before renewing the tax.’

‘Yes, yes, I admit everything,’ I pleaded. ‘But please let me go home. My wife’s not well. She’ll need me to be there this evening.’ I was over-egging it, almost starting to enjoy the whole episode. There was something pleasingly ludicrous about an undertaker being given a rap for an illegal motor. I could see that Thea was aware of some of this – that she felt, like me, that such details were beside the point. A woman had died and been buried, there were wars going on and whole populations starving. The minutiae of vehicle regulations counted for little in the larger scheme of things.

‘Besides,’ Thea persisted, ‘you’re not in uniform. Doesn’t that mean you’re not entitled to throw your weight around like this?’

‘Don’t be stupid.’ Jessica was clearly losing any cool she’d retained till then. ‘If I observe a felony taking place, whether in uniform or not, it’s my duty to confront it.’

‘Bollocks,’ said Thea, earning herself my eternal affection. ‘You just enjoy the effect it has on people.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said the daughter, inflating her bosom with dignity and turning back to me. ‘But the law’s the law.’

‘So, what must I do?’ I enquired humbly.

‘Kwik-Fit will still be open – you can go and get new tyres, and be on your way in an hour or so,’ said the girl briskly.

And it’ll cost me money I didn’t have, I calculated gloomily. The credit card could stand it, just, but I’d vowed to myself not to use it again until the end of the month. The business survived only by virtue of a constant juggling act with the finances, and although I had been able to access Mrs Simmonds’ carefully secured money, things were still very tight.

‘Right,’ I said with a sigh. ‘Where’s the nearest one, then?’

They didn’t know. They weren’t local. Jessica and her boyfriend had invited themselves over to join Thea for a meal in Chipping Campden, all three of them staying in Mrs Simmonds’ house (which I thought slightly dubious, but it seemed they felt perfectly justified) overnight, before departing to their respective homes next day. ‘Or we might even leave it till Sunday, if the weather improves,’ said Thea, happy to share their plans with me. Her daughter rolled her eyes again, obviously thinking I had no need to be told about their personal arrangements.

I was uneasy, even agitated. Money trouble always sent me into a spin, and I also had the worry of Karen and the children expecting me home. Plus there was my usual reluctance to finally detach myself from the person just interred. Normally, this was accomplished quite gradually and painlessly, because they were buried in the field behind my house, and I could stroll around the graves every day and commune with them as much as I liked. This time, I believed I would never come back to this remote little village, never revisit my one-time client, to check that all was well with her. Daft, I know, but there’s something about the dead that makes it difficult to abandon them completely. I liked to know I’d done a good job; that nothing had disturbed their resting place. I worried for Mrs Simmonds’ remains left alone in this corner of land, with careless relatives and uncomprehending neighbours, and the constant niggling worry about foxes and dogs that came from the shallower graves employed for ecological reasons. Mrs S might have earned my respect when she said she quite liked the idea of an arm or leg being taken away by a vixen as a hearty supper for a nest of fox cubs, but I had no intention of letting such a thing happen.

I was also annoyed – as anybody would have been – with the young police officer, who I could not help feeling had been showing off for the benefit of her boyfriend, if not her mother. The detective beau further confused me by appearing sympathetic towards my predicament, whilst studiously remaining silent. Where Thea was rapidly becoming a confirmed ally, he seemed, if not quite on my side, then far from impressed by the eager Jessica. The criss-crossing currents of emotion and motivation made me feel tired. The cold wind kept blowing, with a few drops of rain in it, hitting the side of my face. All the mourners had gone, leaving us, a motley foursome, to bid a final farewell to Mrs Simmonds.

‘Oh, for heaven’s sake,’ burst out Thea, after a moment or two of silence. ‘You started this, you sort him out.’ She was addressing her daughter. ‘Find out where he can get some tyres, and show him how to get there. The whole thing is completely ridiculous, and you know it.’ She gazed impatiently at the sky, as if appealing for celestial witnesses. ‘Since when did the police become so hopelessly sidetracked by stupid little details like car tyres? No wonder you get so little respect from the public. This is a prime example of where it’s all gone wrong.’

Detective Paul cleared his throat warningly, and his eyes widened. He was big, and muscular, filling the blue rugby shirt he wore with bulges that could only come from serious physical power. I imagined him felling a runaway criminal with a forceful tackle that showed no concern for subsequent cuts and bruises.

Jessica’s bosom heaved again, and she clenched her lips tightly together, before managing to speak. ‘Mr Slocombe, it’s up to you what you choose to do next. I’m going to file a report to say I cautioned you about the condition of your vehicle and the failure to show a valid tax disc. If you report to a police station within forty-eight hours, with proof that the tyres have been replaced, that will be enough. No further action will be taken. Do you understand?’

She was polite and calm. I nodded weakly, feeling I’d had a reprieve from a prison sentence. ‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘Do you want me to sign anything?’

‘That won’t be necessary.’

‘Well, goodbye then,’ I said, looking hard at Thea Osborne, wondering if I had caused a major family rift, and whether there was anything I could do to mend it. ‘Thank you very much. I mean – it was nice to meet you. I’m sorry if I’ve made you late.’

‘It was a very nice funeral,’ said Thea gently. ‘Dignified but human. Just the sort of thing I’d like to have myself.’

‘Oh, God, Mother,’ groaned Jessica. ‘Don’t start on that now.’

Somehow they appeared to have evened things up, to have established a balance between them that was free from animosity. I smiled carefully.

It was close to two o’clock, the burial having begun at twelve-thirty, and somehow the subsequent business having occupied nearly an hour. Nobody had had any lunch, especially me, and my stomach was complaining. The grave was already being discreetly filled in again by the efficient local man, assisted by young Jeremy, and there was absolutely no further reason to stay.

‘I’d better get on, then,’ I said. ‘I’ve kept you for ages, haven’t I? I’m so sorry. You must be hungry by now.’

Nobody replied, but Thea met my eye with a little nod of understanding that seemed close to an apology for her daughter. I went back to my delinquent vehicle and climbed in. There was a Mars bar in the glove compartment, and I retrieved it and tore off the paper before trying to start the engine. All I needed was the overzealous police constable to get me for eating while driving. According to Maggs, that was one of the latest batch of misdemeanours you could be stopped for.

The country lanes were confusing, and I forgot to check the map before finally setting off. All I knew was that I needed to head south, and my sense of direction was just about reliable enough to ensure I got that much right. I remembered passing through Stow-on-the-Wold on the way up, so hoped to find a sign directing me back that way, once I’d reached a more major road.

All of a sudden I felt any sense of urgency fall away. Karen was quite capable of collecting the kids from school and giving them their tea. Maggs would handle any phone calls or visits to the office. It was Friday, and although my life hardly followed the normal working pattern, there was still the general air of relaxation, if only because we could forget about school uniforms and packed lunches for a couple of days.

It was over three years since Karen had come home from hospital, pale and fearful after being shot in the head at close range. Nothing vital had been destroyed, and at first the doctors had assured us that her periods of blankness and problems with eating and sleeping were the result of trauma, rather than physical damage. The very fact of her still being alive had carried us through several euphoric weeks. And she did slowly get better, although the lack of appetite persisted and the resultant loss of weight alarmed me. She had always had lovely creamy shoulders and neck, well padded for a child’s head to rest on. She had been strong and nurturing, a perfect wife and mother. The new Karen was very different, her efforts to play the same role as before often painful to observe. I watched her self-assessments, whereby she calculated how much energy she had that day, and where the priorities should lie. She tackled everything head-on, from some deep sense of obligation, but there was no joy in her. It took me a long time to see that the euphoria had been all mine, and that my wife was no longer sure about the purpose of being alive.

The only answer she could find to that question lay in the children. Stephanie and Timothy, who had been four and three at the time of her injury, needed her irrefutably.

I decided to stop at a pub for a sandwich and drink before joining the M5 and pressing on home, if I could find one still serving food at that time in the afternoon. A detour on a whim down a small road leading to a village, the name of which I never noticed, took me to a plain-looking hostelry, which offered me a choice of ham or cheese in white or brown. I drank a large quantity of very expensive apple juice, and hoped I could reach home before my bladder started to bother me.

The motorway was busy, it being a Friday afternoon, but nowhere near as bad as it would have been a year or two earlier, before failed businesses, high-priced fuel and general economic gloom took so much commercial traffic off the roads. No longer did people head in their thousands for the South-West the moment a nice weekend was promised. Admittedly, this rush had never really gone mad until after Easter, but given the reduction in lorry movements, and the near disappearance of small vans dashing hither and yon on mysterious business, the traffic kept moving very nicely.

Home beckoned strongly on the final stretch. The children would greet me like Irish setters, as if I’d been away for months. Karen would smile and tell me about her day. Maggs would wait in the background, and then fill me in on any developments. I had never seen myself as a patriarch, but nonetheless, there was a pleasing sense of being absorbed into a world of women and children, all focused on me. The hunter coming home, the returning warrior, the breadwinner with his sack of sustaining goodies over his shoulder.

And so it proved, with only minor deviations. Karen had a headache, which was not unusual, but pained me to witness. Her hair, once thick and tawny, had thinned and faded after the removal of much of it in the hospital. Her suffering head throbbed almost visibly, the crease in her brow suggestive of a heavy weight crushing her crown. Stephanie had lost another tooth, the resulting gap somehow ghastly in my once-perfect little daughter. She and I had enjoyed a close bond from the outset, when Karen returned to teaching and I was setting up the business. My little toddler girl would play calmly in the office while people came to discuss burials. Looking back it felt like an idyll in every respect.

Timothy had been in trouble at school – again. He could never explain his sudden bouts of violence against other children, but we assumed it could only be a legacy of Karen’s injury, an inchoate rage against the loss of the trouble-free life we had known in his first years. When I suggested that it might simply be that he was too young to be confined to a classroom and expected to conform to the rules of an institution, no matter how benign, Karen defended the system, from her standing as one-time professional teacher.

I went to my office, to find out how my weary colleague had fared. Maggs had nothing to report, which in itself was a disappointment. She smiled determinedly, and asked about my trip to the Cotswolds.

‘I got into trouble with the police,’ I said, anticipating her reaction.

She eyed me attentively, her brown face slightly tilted. ‘Speeding?’ she guessed.

‘Nope. I wasn’t even in the car at the time.’

‘Tyres,’ she nodded, pleased with her cleverness. ‘I knew they weren’t legal.’

‘Right. And tax. It was a policewoman, at the funeral. Sort of. Her mother was actually there first, and she came along later, for some reason. With a detective boyfriend.’

‘Bummer,’ said Maggs carelessly. Like me, she had a healthy disregard for life’s trivialities. The small stuff passed us by where other people seemed to find it desperate. They would fight over who did the washing-up, or whether the toothpaste was in the right configuration. We chose instead to focus on the larger issues of grief at the utter finality that came with death; the future condition of the planet; the obligations we had shouldered in our work and our relationships. Maggs and Karen and I had been a forceful trio when we founded Peaceful Repose, carrying all before us. If Karen and I had grown tireder and older since then, Maggs continued just as before, an indispensable inspiration and support. Even now, after twenty-something hours with no sleep, she was reliably focused.

‘It’s daft, though,’ I persisted. ‘When the city centres are impassable and the youth of today are feral monsters, why waste time on model citizens like me?’

‘Forget about it,’ she advised. ‘And have a nice weekend. I’ll see you on Monday.’

‘Yes…you too,’ I said, never doubting that I would indeed see her on Monday.

I went back to take over from Karen. She had put some potatoes on to boil, but done little else towards preparing us a meal. ‘Chops?’ I suggested, looking in the freezer.

‘If you like.’

‘I’ll turn the spuds off for a bit, then, or they’ll be done too soon.’

‘OK.’

I flew around the kitchen, thinking about the food. I could gather some mint from the garden, and fish some frozen runner beans out for the veg. It was simple, basic stuff, which Karen could have done standing on her head before she was injured. Now she so easily lost focus, so that peeling and boiling potatoes could seem to her all that was required for a family meal. We had often sat down to unadorned pasta, or a large quantity of grilled bacon with nothing to go with it. I had quickly learnt to have instant sauces, frozen peas, tins of beans and sweetcorn and soup stacked in the cupboards ready to add to Karen’s partial meals. I had also acquired a microwave oven, despite a strong resistance to that sort of cooking. Karen and I had been united in choosing a simple lifestyle, with slow cooking, home-grown vegetables, minimal use of technology. It went with the ethos of the business, after all. But much of that had changed over the past three years. The world itself was in deep confusion over the demands of the environment, the global recession, the price of oil – the word ecological had begun to seem old-fashioned, along with alternative and even organic. My children were catching up with the digital age, while Karen and I struggled to cling to the ideology that had been so important to us.

After the meal, I put the children to bed. They shared a room, and I read them a story sitting on the edge of Stephanie’s bed. It was a chapter of TheJenius by Dick King-Smith, an old favourite of my daughter’s. But I noticed that it was Timmy who listened more intently, laughing at the witticisms, his eyes fixed on my face as I read.

‘What are we going to do tomorrow?’ Stephanie asked me as I tucked her in.

‘I don’t know. What do you want to do?’

‘Go swimming!’ shouted Timmy.

Stephanie and I both groaned theatrically. Timmy’s passion for water was inexplicable to us both. Trips to the local swimming pool were strictly limited to times when it was inescapably Timmy’s turn to choose what we did. Karen carefully monitored the fairness of such decisions.

‘Not your turn,’ said Stephanie emphatically.

‘Yes it is.’

‘We went swimming last weekend,’ I said. ‘And you lost your rucksack – remember?’

It was chastening to see how his face fell. ‘Oh, Tim,’ I said. ‘Don’t worry. It’s the holidays next week – we’ll go swimming three times, I promise.’

‘Daddy!’ protested Stephanie. ‘That’s too much.’

‘Maggs can take me,’ my little boy suggested. ‘She likes swimming.’

It wasn’t true. Maggs had no more fondness for the noisy, chlorine-imbued atmosphere of the local baths than I did. But she liked Timmy, and put herself out for him as she had never done for his sister. Maggs, more than anybody, had noticed how badly Timmy had been cheated by the injury to his mother, and had swiftly, unobtrusively, done her best to fill the gap. The bond between them was seldom openly acknowledged by any of us. It was simply taken for granted as one element in our lives.

‘Don’t bank on it, Tim,’ I cautioned. ‘She’s only just got back from holiday, and she’ll have a lot to do. I think we’ll just have a lazy weekend. We could go for a walk and see if we can find catkins and sticky buds.’

Neither child manifested any enthusiasm for my suggestion.

Chapter Three

It was nine-thirty on Saturday morning when a sharp rap sounded on the front door. We almost didn’t hear it because Timothy was shouting and Stephanie had the TV on far too loud.

A policeman stood there, and I sighed impatiently. ‘For heaven’s sake,’ I snapped. ‘Give me a chance.’

‘Mr Slocombe?’ he asked calmly.

‘Yes, yes. Look, I’ll get the tyres replaced today, OK? There’s no need for all this harassment.’

‘Sir, this is not about tyres. It concerns a burial in Gloucestershire yesterday. I understand that you were responsible for it.’

‘What? Yes. Mrs Simmonds. So what?’

‘There has been a complaint, sir. From the council. They contacted the police with a view to pressing charges.’

My impatience escalated. This was familiar territory. ‘The burial was entirely legal,’ I told him. ‘The council has no jurisdiction over what was done. Believe me, I know my rights on this. It’s my business, after all.’

‘The council owns the land, sir. You have committed a trespass.’ His face relaxed a little as he heard his own words. ‘Quite an unusual trespass at that,’ he added.

My mind was racing. ‘But it’s too late,’ I protested. ‘You can’t just move a grave once it’s been established. There’s nothing to be done now.’ I suspected that I knew the law on this matter better than this officer did. ‘There’d have to be an application to the Home Office for exhumation. Nobody does that lightly.’ Indeed, such a procedure was the stuff of nightmares – literally. It was one of my greatest dreads.

‘We need you to explain that to the man from the council,’ he agreed. ‘He might listen to you.’ His expression suggested that this was unlikely, and I sighed.

‘So I’m not under arrest, then?’

‘Trespass is not a criminal offence, sir. But the…well, delicate nature of this case means we would prefer for you to come and talk it through with Mr Maynard, face-to-face. Get the whole matter settled quietly.’

A suspicion struck me. ‘He wants us to pay for it – is that what you’re saying? He’ll leave the grave undisturbed if we pay some sort of rent for the land?’

‘Not for me to say, sir.’

I was inwardly cursing myself from the moment of the revelation that the land had not belonged to Mrs Simmonds. It had not occurred to me to ask for proof of ownership, which seemed idiotically sloppy, in retrospect, although Mrs Simmonds had clearly said the field was hers. She had deceived me, I realised, with a sickening sense of having been betrayed. If she had admitted that there was the slightest chance of local council involvement, I would have refused to accede to her wishes. The first rule of one-off natural burials in anything other than a cemetery or churchyard was – Don’t Tell The Council. Don’t ask their permission, don’t casually phone them to check that it’s all right with them. Leave them out of it. Generally speaking, burials fell under the jurisdiction of the Parks and Recreation Department, often headed by an earnest little jobsworth who would seize this deviation from the usual run of daily paperwork with relish. Mythical regulations about waterways and notifiable diseases would surface and proliferate until any chance of conducting the proposed burial vanished under the weight of obfuscation. There would have to be specialist reports on the density of the soil, the potential consequences for rare moths or molluscs, the appalling difficulties involved in parking eight or ten vehicles on the roadside for the funeral, delaying everything so drastically that the proposal could only be abandoned.

And the law was, in effect, on our side. Once the burial was accomplished, it was pretty well permanent. Retrospective complaints could safely be ignored. Usually. The fact that this land was unconsecrated meant an exhumation could be more readily carried out than if the grave had been in a churchyard, although it would still be a serious procedure, with any amount of paperwork. I became aware of a dawning collection of doubts. I had made a mistake, a gaffe, and was already quailing inwardly at the potential consequences.

The police did not drive me to Broad Campden in a locked car with a stout female officer beside me. They let me go by myself, in a car with expired road tax and bald tyres. The man on my doorstep insisted I had to go and hear what Mr Maynard had to say. ‘He said he’d meet you by the grave at eleven-thirty. I think that gives you plenty of time, doesn’t it?’

‘Can’t I just phone him?’ I pleaded.

‘Sorry.’ He shook his head.

‘It’s Saturday. Why isn’t he at home planting potatoes?’

A shrug suggested that I was wasting time for both of us. ‘All right,’ I conceded, as if I had a choice. ‘Let me go and tell my wife.’

Karen took it serenely. ‘What a pain,’ she said. ‘When will you be back?’

I visualised the tedious drive, an hour and a half each way. ‘Hard to say,’ I replied. ‘But definitely long before dark.’ Darkness fell at about seven, the equinox less than a week away.