7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

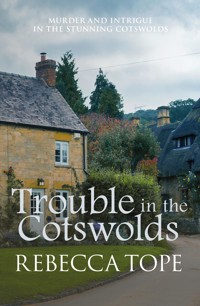

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Cotswold Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

Thea Osborne's latest house-sitting assignment is a little different to the rest. Along with her spaniel, Hepzie, Thea finds herself in the village of Chedworth. She is tasked with creating an inventory of Rita Wilshire's possessions, requested by her son, Richard Wilshire, after moving her into a care home. All goes to plan, until Thea and her fianc , Drew Slocombe, find Richard dead in a barn. When family members come knocking, Thea and Drew struggle to give them answers. The Wilshire family has its own past and, whilst Thea knows it is not really her business, she cannot help but become involved in the case. Was Richard's death suicide? Or something more sinister? When the clues lead them in circles, Thea's relationship with Drew is put to the test. But there is a crime to solve, and neither of them is willing to give up just yet.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 423

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Guilt in the Cotswolds

REBECCA TOPE

Dedicated to Pat and in fond memory of Beulah.Also with special thanks to Daphne Abbley for help with Chedworth topography

Contents

Author’s Note

As with other books in this series, the privately owned properties in the story are products of my imagination, with the exception of the large barn on the road to Yanworth. That does exist.

Prologue

Drew Slocombe was searching for a care home for the elderly on the outskirts of Stratford-upon-Avon, using a satnav for the first time. His daughter Stephanie, nine years old, had shamed him into it. His shame only increased as he realised how much easier it made the task than it would have been roaming the streets with the help of an inadequate map.

Mrs Rita Wilshire was waiting for him, along with her son Richard. Together they were to draw up a prepayment plan for Rita’s funeral. When the time came she was to have a grave in Drew’s burial ground near Broad Campden – assuming it was fully operational by then. Otherwise, she was content to rest in the Somerset field known as Peaceful Repose, where Drew had already buried close to seven hundred people in the years since Stephanie had been born.

It was early September and the sun was shining. At Richard’s suggestion, they settled on canvas chairs under a handsome cedar and conducted the business in the open air. ‘Rather as my funeral will be,’ smiled the old lady. ‘I do hope there’ll be fine weather for it.’

Drew responded warmly, pleased to have such a stalwart customer, who accepted the certainty of her own death while expressing a hope that it would not be unduly soon. ‘I would think I might last another five years,’ she had said at the start. ‘There isn’t a great deal wrong with me, apart from my legs.’

‘You’ll see your centenary,’ her son assured her, not quite so phlegmatic about the matter. Richard Wilshire struck Drew as a rather dull character, rendered uncomfortable by this deviation from the usual practice. Not so much the advance planning as the choice of an unorthodox manner of disposal. His mother insisted on a cardboard coffin and no religious input. As people so often did, she began to reminisce about previous funerals she had experienced. ‘My sister died very young. There was a great deal of pomp and circumstance, no expense spared. But she was just as dead in the end. Poor Dawn. She’d be ninety-six now. I still remember her birthday every year.’

Drew ran through the costings of the services he could provide, but counselled against fixing too many details at this stage. ‘Leave something for your son to do,’ he said. ‘Like deciding about music.’

‘I’ve always liked the idea of a lone Scottish piper,’ she said with a distant gleam in her eye. ‘But I wouldn’t insist on it.’

Richard Wilshire rolled his eyes, and gave her a gentle poke in protest. ‘I make no promises,’ he said. ‘Since we don’t possess a drop of Scottish blood between us.’

‘Irish, then. Or even an English one. I don’t see that our blood matters, anyhow. It’s just a lovely haunting image.’

The business concluded, Drew stayed a little while longer, because he was in no rush and he liked these people. Mrs Wilshire had only been in the home for a week or so, and was still intoxicated by the changes to her life. ‘I seem to get the prize for the most compos mentis,’ she laughed. ‘But there are two other excellent bridge players. I’ve only won two rubbers so far. My partner isn’t too hopeless, luckily. She was delighted when I arrived, and they could make up a table. We’re both improving considerably.’

‘It’s a lovely spot,’ said Drew, looking around. The town of Stratford was close by, but the home had generous grounds with several large trees and flower borders. ‘Where did you live before?’

‘In the Cotswolds. A village called Chedworth. I keep expecting to be overcome with homesickness, but so far everything’s far too pleasant here for that to worry me. I admit I miss some of my things, and it’s very strange knowing I no longer own the walls around me. I hadn’t appreciated how much ownership matters. Probably a very incorrect attitude these days, but there it is. And besides, the house is still there, and Richard would never sell it while I live. Would you, dear?’ There was a hint of challenge in her eye, thought Drew. Or perhaps something even darker, like a threat.

Richard sighed and shifted in his canvas chair. ‘Not unless we run out of cash, and then there won’t be any choice. This place isn’t cheap, you know.’

‘And the family isn’t poor. You’ll get the house eventually. I just couldn’t bear to think of other people in it while I live.’

Richard sighed again. It was clear to Drew that he thought the old lady was being unreasonable.

The subject changed, and Mrs Wilshire pointed out her room, on the ground floor with a window overlooking the lawn. ‘My pathetic legs qualified me for the ground floor,’ she said. ‘It’s not long now before I’ll be needing a wheelchair nearly all the time.’ She had made it to the garden seat with the aid of two sticks, at a very slow pace, the two men following attentively behind.

Shortly afterwards, Drew made his departure, with Richard Wilshire accompanying him to his car. ‘Back in a minute, Mum,’ he said.

‘No hurry, dear. I’m quite all right here. Thank you, Mr Slocombe. I don’t expect I’ll see you again, although that would be a pity. I very much enjoy your company.’

Drew nodded a rueful agreement. ‘Perhaps I’ll drop in on you one day,’ he said. ‘If I’m ever this way.’

‘Oh yes – do. I’m sure we could always find plenty to talk about.’

Richard waited until they were out of earshot, standing beside his big Honda four-wheel drive. He bent down and felt underneath the chassis, below the driver’s door. ‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘It’s a habit I’ve got into. I’ve lost so many car keys in my time. Now I just attach them like this.’ He showed Drew a small metal box that had somehow stuck magnetically to the car. ‘And I keep two spare sets at home for good measure.’ He pulled a self-deprecating face.

‘Seems like an excellent idea to me,’ said Drew. ‘So long as the magnet’s nice and strong.’

Richard then began to speak rapidly. ‘It was very good of you to come like this. I know you’re based in Somerset. This must be taking up virtually the whole of your day.’

‘No problem,’ Drew assured him.

‘The thing is, we’re such a small family, and so many of Mum’s friends have gone now, that it seemed to make sense to get all this settled. I just hope she hangs on until you’ve opened the new burial ground. She’d be so much happier close to her old home.’

‘Chedworth – is that right?’

Richard nodded. ‘You heard her. There’s a great big house standing empty, except it’s not actually empty at all. It’s still full of all her stuff. She could only bring a tiny fraction of it here with her. I need to find somebody to deal with it, I suppose. Though Mum seems to think it’s fine as it is. She’s a bit irrational where that side of things is concerned. There’s no way I can just get a clearance outfit to take it off our hands. I dread the day when we have to sell the house, but if she lives more than a year or so, we’ll have to, to pay for the home.’

‘So what would “dealing with it” actually entail?’ Already Drew was having an idea.

‘For a start, I need to know what’s there. It goes back more than half a century. I was born there, and as long as I can remember there’ve been wardrobes and chests stuffed with all kinds of clothes and linens and I don’t know what. Not to mention the attic, which has precious heirlooms, according to Mum. I can’t just leave it all, can I? Much as I might like to,’ he added in a low tone.

‘I might know someone who could help,’ said Drew. ‘If you’re interested.’

Chapter One

Thea was lost; lost and late. It was getting dark and the narrow lanes of Chedworth began to close in on her, the village seeming to come to an end only to start again a little further on. She should have paid better attention to the instructions, instead of blithely assuming she knew the area well enough by now to avoid any difficulty. It had become apparent in the past five minutes that there was both a Chedworth and a Lower Chedworth – which came as a big surprise. Small roads wandered off in all directions, including dramatic downward plunges. Richard Wilshire would be waiting impatiently for her in the stone house set on a small road that went nowhere, close to the church. He had ordained five o’clock as the required moment for her arrival. ‘Then we can settle you in for the night,’ he had said, with a laugh that had a trace of snigger in it. His instructions, taken down during a phone call, were scribbled on a scrap of paper beside her. ‘Next left after Hare and Hounds pub. Right at the Farm Shop – straight through Chedworth until Seven Tuns pub.’ No hint of distances or useful landmarks. She had met a T-junction soon after the right turn, of which there was no mention in the instructions. A defunct red telephone box beside the road had ‘Defibrillator’ blazoned across it, which made her smile. And then the road had carried on and on, around bends and up hills, passing the usual old stone houses with no lights on inside. Anyone, even the most unimaginative, could quite easily believe themselves to have slipped back a century in time. The existence of motorways, airports, bright lighting and high speed had all faded into a far-off realm. Here in this monochrome twilight world, it was easier to revert to a slower, simpler mode. As if to emphasise this, there were signs announcing ‘Twenty is Plenty for Chedworth’ in reference to the speed limit.

It was half past five in early October, which was still an hour short of the moment the sun sank over the edge of the world. But it was a cloudy day and there were trees and high banks and houses on all sides, closing out the lingering light. It felt later than it was. ‘Not sure I like the atmosphere here,’ she muttered to Hepzibah, her constant companion. The spaniel on the passenger seat gave her a liquid look of sympathy. But the houses were as lovely as those in most other Cotswold villages, some of them impressively old and weathered. As she hunted for the church, which surely ought to be on an elevation somewhere visible, she passed clusters of closely packed homes, with never a glimpse of a human being. Seconds later she found herself in virtually open country, with no buildings visible. This lasted only a short time before another typical house came into sight, followed by several more. The stop-start nature of the place was disorientating.

Chedworth, then, was nothing like Stanton or Daglingworth, Hampnett or Broad Campden – all of which she had come to know in the past year or so. All of which were also remarkably close by, many within walking distance. The way each settlement could acquire so distinct a character was a mystery.

Richard Wilshire was in his late fifties, a solid man of limited horizons. That much Thea had gleaned from information received from Drew Slocombe, her soon-to-be husband and acquaintance of Mr Wilshire. It was thanks to Drew that this commission existed in the first place.

‘He’s got an aged mother who’s just moved into a residential home,’ Drew had explained. ‘She heard about the natural burials, and came to me to arrange her funeral when the time comes.’ Drew had achieved the first stages of establishing a second burial ground in the heart of the Cotswolds, taking pre-planned customers, but so far only one grave lay there. In the process of funeral arranging, it had transpired that Old Mrs Wilshire was leaving behind a substantial house containing a lifetime’s possessions. Her son found himself unequal to the task of sorting these items into any meaningful categories. Young Mrs Wilshire – Daphne – no longer regarded the fate of her mother-in-law as relevant. She and Richard had separated five years previously and she was living with a man called Nick. ‘Are you keeping up?’ Drew had checked with Thea at this point.

‘Easily.’

‘Good, because there’s more.’ He went on to report that there was a daughter named Millie who was twenty-five and – according to her father – so completely appalled by the treatment of poor old Granny that she couldn’t bring herself to go near Chedworth ever again. ‘All of which explains why a certain Thea Osborne is sorely needed,’ he summarised. ‘It might not be exactly house-sitting as we know it, but it’s well within your capabilities.’

She had given him a look. ‘You’re telling me the job has expanded into that of house-sorter and house-clearer, as well. Which might include heavy lifting. Do I get paid extra?’

‘I left that to you to negotiate. I will, of course, come and help with anything heavy.’

Her reply was a familiar one. ‘How will you find the time to do that?’

‘I’ll manage it somehow,’ he said, as usual.

Drew and Thea had been together – emotionally if not logistically – for well over a year. The summer just ended had seen them spending more and more time as a family, with his two children rapidly accepting her as a fixture. Their wholehearted enthusiasm for her and her dog was almost unnerving. The first week of their school holidays that summer had been spent with Thea in a house-sit that had passed so idyllically she sometimes wondered if it had all been a dream. The four of them squatted in a large Cotswold house in Farmington in the most perfect weather with a pack of Siamese cats. On the last day, Drew had recklessly suggested marriage. In a surge of euphoria, Thea had accepted. Three months later, she was still uncertain as to whether it would ever actually happen.

The Seven Tuns pub occupied a site near another T-junction. Peering at the final words of her directions, Thea read, ‘Left, then follow road past church. House on left, easy parking.’ Not seeing the church, she drove blindly to the left, up a steep little road that showed virtually no sign of having changed since before cars were invented. Suddenly, the church was right beside her, and all became clear.

She finally knocked on the door at five-fifty. Richard Wilshire brushed aside her apologies for lateness and led her into the living room. ‘You come well recommended,’ he assured her. ‘Good in a crisis, they said about you. Ready for anything.’

She flinched at the they. Who else, other than Drew, had been talking? ‘It isn’t exactly what I’m usually asked to do,’ she reminded him. ‘There are professionals for this sort of thing. They take all the stuff in return for leaving a nice empty house.’

‘I don’t want that. This isn’t about clearing the house. We’re not disposing of anything other than absolute rubbish. First, I need an inventory.’ He gave an embarrassed laugh. ‘I lived here all my life, until I married, but I still have no idea what’s in some of the cupboards and boxes. It never really occurred to me to wonder. But now – well, I can’t leave it any longer.’

Thea attempted to look capable, sympathetic and responsible all at the same time.

‘Be warned,’ Mr Wilshire went on. ‘My mother lived here for seventy years and there are places that probably haven’t been touched for most of that time. How are you with spiders?’

‘Not great,’ she confessed. ‘But better than I used to be.’

‘The attic is the worst. Mum hasn’t managed the stairs for a few years now. I should have gone up there myself, but I never got around to it. Take a killer spray with you, if you like.’

‘No, no. I don’t like to kill the poor things. I’ll be all right if I’m forewarned. The dog sometimes catches them for me, if they’re really huge.’

They went on to discuss the procedure she was required to follow. ‘I don’t think there’ll be very much rubbish, but what there is can go straight into bin bags,’ he said. Then he suggested she set aside items of obvious value; sort through papers (important and otherwise), make a list of items that were broken but potentially useful, and another list of whatever she found in the unexamined cupboards and boxes. She wrote much of it down and asked several questions.

‘I understand Mr Slocombe’s going to join you at some point,’ he said.

She noted the formality with interest, having assumed the two men were on better terms than that. ‘He’ll try,’ she said. ‘It won’t be easy for him to get away if things are busy.’

‘I’ve prepared the main bedroom for you.’ His tone implied that this had been a tremendous achievement, for which she owed him much gratitude. ‘Turned the mattress over, so it ought to be okay.’

‘Thanks.’ Visions of an incontinent old woman sleeping on that mattress until a month or two ago made her uneasy. But it sounded as if all the other rooms were even less habitable.

‘Listen,’ he said with a tormented look, ‘I know it’ll be hard work, and I should be doing it myself. All this stuff – it doesn’t matter to me. I’m not sentimental about most of it. But there’s sure to be a few … triggers, if you know what I mean. Things I’ve forgotten, from when I was a kid. There was a time when I tried to get her to throw stuff away, but I gave up long ago. Since then I’ve just closed my eyes to it, and stuck to the routine maintenance business. You know – making sure the electrics are okay and the plumbing works. The house is in a mess, basically. It hasn’t been decorated for decades. I made her take up all the rugs, in case she tripped and fell. They’ll be up in the attic. But I know I could have done a lot more …’ He tailed off miserably.

Thea looked around the living room, where they were sitting together on a shabby old sofa with the dog between them. Richard Wilshire evidently saw no reason to protest at a spaniel on the upholstery. The wallpaper was faded. There were piles of magazines and books on a window seat, and a clutter of old-fashioned furniture on all sides. The curtains were dusty and the skirting boards grimy. ‘Didn’t she have a home help or something?’

He shook his head. ‘A girl came in once a week for a bit, but they fell out. My mother liked to think she could do it all herself. She never got the hang of the vacuum cleaner, though. Or the splendid new washing machine. She always loved the twin tub, but it died a couple of years ago. She’s stuck at about nineteen seventy, in a lot of ways.’

‘She washed clothes by hand?’

‘Mostly, yes. I supervised a big wash in the machine whenever I came over – sheets and bigger things. She always used an antique carpet sweeper. It does work surprisingly well.’ They both glanced down at the floor, which was quite acceptably clean.

There was something rather nice about it, Thea discovered. A little island of social history, ignoring such new-fangled developments as automatic washing machines. ‘I don’t suppose she has a computer?’ she said.

‘Oddly enough, she has. She had email almost from the start – must be twenty-five years or so now. She’s kept everything on discs, all these years. Most of them are obsolete, of course. She’s got a smart new laptop now. She’s determined to keep up with relatives and old friends. Apparently half the residents in the home have got mobiles and tablets and the latest gadgets.’

‘How old is she?’

‘Well over ninety.’ He sighed. ‘The home’s really nice, you know. But I still feel desperately guilty about it.’ His eyes grew shiny. ‘With the best will in the world, they can’t let her take more than a tiny fraction of her stuff. She’s going to be so lost without her things. She still has a very sharp mind.’ He rubbed his face. ‘Sometimes I think it’s kinder when the wits go first, although I suppose it isn’t. My mother’s legs have let her down in the last year or so. And her sense of balance isn’t what it was.’

‘Does she know you’ve got me sorting out the house?’

He grimaced. ‘I’m afraid I didn’t have the courage to tell her. She would want to be consulted about every single thing. I mean well, believe me. I know some people think I should wait until she … you know. But she’s never coming back here, so it seems silly to just mothball everything. Besides, we might need to sell up at short notice, although I hope not.’

‘So what’ll you do with it all?’

‘No idea. I’ll make a plan when I know exactly what there is. Nothing’s going to happen soon.’

‘You shouldn’t feel guilty,’ said Thea bracingly, aware that he was deeply unhappy. ‘She’ll have all her comforts there – all her meals provided. Warm. Safe. It must have lots of advantages.’

‘All true,’ he said. ‘And she mostly likes the place. But it’s such a huge change, and old people hate change.’

‘No escaping it, though. There’s nothing you can do about it.’

He gave her a look that startled her. It contained something close to dislike for a moment. Then he blinked and it was gone. ‘It was her own decision. I never pushed her into it. But people will think I did. “Packed his old mum off into a home” – that’s what they’ll be saying. They’ll assume I want to get my hands on the house. It’s worth a small fortune, even in this condition. And I don’t have to share it with anyone else.’ The last words carried additional emphasis. Again, they both looked around the room. There were pictures on the wall, a Victorian clock on the mantelpiece, a piece of china that Thea thought could be Moorcroft, on a small table. ‘But all that can wait,’ he finished.

She opted for a change of subject, asking which services were still connected, and which not. ‘No phone,’ he said. ‘But the power’s on, and there’s an immersion heater for hot water. I didn’t think it was worth getting the Aga started, although I’m afraid the kitchen does get cold without it. You can have a log fire in here – there are still some logs in the shed at the back. It’s very effective once it gets going. I hope it won’t feel like an abandoned house that nobody loves.’

‘It doesn’t,’ she assured him. ‘Not with all the furniture still here. You could probably let it out to holiday visitors,’ she mused. ‘They’d keep it alive, so to speak.’ She thought of Drew’s neglected property in Broad Campden, which would feel much colder and more cobwebby than this one.

‘Did you bring any food with you?’ he asked.

‘Not much. Milk, biscuits, tea bags and a couple of things to keep me and the dog going until I can buy something tomorrow. I thought there’d be a shop somewhere nearby.’

He frowned. ‘There’s the farm shop, that’s all. It has pies and things. Bread. And there’s the pub, of course. They’ll feed you. Oh, and the Roman villa has a cafe, which I suppose is open for a few more weeks yet.’

‘I’ll manage,’ she said airily. Food was seldom a high priority with her, although she was prone to sudden attacks of insatiable hunger when nothing else mattered but to eat something.

‘There are phone numbers on this list,’ he said. ‘You won’t need them, I’m sure, but I always think it’s good to have them. There’s my mother, my daughter and the usual plumbers and so forth. Just in case.’

‘Thanks,’ said Thea flatly. The same thing had happened in almost all her house-sitting jobs. People thought a phone number could solve all kinds of difficulties. And sometimes they were right, she had to admit.

The man pumped his arms, as if winding himself up. ‘Well, I have to go. I’ve got a visit to make. Then home, I suppose.’ He didn’t look particularly eager. ‘I’ve left my dogs shut in, and they’ll bark if nobody turns up. I think Millie said she’d be home tonight, but I’m not sure.’ He tailed off, looking vague and distracted.

‘Where do you live?’

‘Stratford – half a mile from my mother’s care home. It’s only about forty minutes away from here, if you need me. But I’m going to be snowed under with work for most of the week, so try to manage, okay? If you do need me, I could drop by on Monday, at a push. Oddly enough, I’m back here again tomorrow, but I won’t have a spare moment.’

‘What do you do, by way of work?’

‘Oh, I’m a vet.’

Thea thought of other vets she had dealt with in recent times, and tried to fit this one into the general stereotype. He had clean hands and tweedy clothes. But he didn’t strike her as particularly outdoorsy. She cocked her head, inviting more detail.

‘I work for DEFRA, mostly, testing cattle for TB. I’m officially part of a practice in Stratford, but these days I don’t do very much with them. There’s so much TB around now that it keeps me pretty busy.’ He shook his head and sighed. ‘Awful business. I have to go to farms and check their animals. I’m doing a follow-up visit in Yanworth tomorrow, before dashing over to Chipping Norton, and somewhere else I can’t remember for the moment.’

Thea could not suppress a grimace. ‘I bet you’re popular,’ she said with heavy irony. She gave him a considering look. His soft pink hands gave him a hint of vulnerability that could make him even harder to like or forgive if he landed some harassed farmer in trouble. ‘Only doing my job,’ he would plead, and they would fume helplessly rather than hitting him.

‘They hate me,’ he agreed. ‘With reason, sometimes. The test is notoriously inexact, so we destroy far too many healthy animals. Nothing more heartbreaking, and there’s nothing I can say to make it better. I seem to spend much of my time defending the indefensible.’

‘Do you have to travel much? I mean – do you have an area to cover?’

He nodded. ‘It’s mostly the whole of the Cotswolds. I’ve got it easy compared to some. Farmers round here aren’t half as curmudgeonly as in Yorkshire or Cumbria.’

‘It certainly doesn’t sound boring, anyway,’ she said, having always believed that the very worst fate that could befall a person – except for getting themselves killed as her husband had done – was to have a boring job. ‘And I’ll try not to bother you. I’ll have everything in nice piles and comprehensively listed for you by this time next week.’

‘Thanks. I really do appreciate it.’

He left her then. She and Hepzie watched him disappear into the darkness, and then closed the door. ‘Here we are again,’ said Thea. ‘Early start tomorrow, my girl.’

Chapter Two

Unusually, she had arrived on a Thursday. ‘It doesn’t matter to him what days you do,’ Drew had said. ‘And that means you can settle in and get started before I come over for the weekend. If I do,’ he added, holding up crossed fingers, ‘it’ll be down to Pandora.’

The name always made Thea smile. It belonged to a temporary assistant who was standing in for Maggs Cooper, because Maggs had recently produced a baby daughter. Pandora was fifty-three and immensely efficient. She had no difficulty with dead bodies, coffins, grieving families or unreasonable requests regarding the positioning of a grave. She was equally good with Drew’s children, and was infinitely available thanks to a recent divorce and her own two sons having left home. She had always lived in Dorset, the move to neighbouring Somerset a major midlife adventure.

The probability of having Drew to join her on the Saturday, albeit with his children, was a strong motivation for Thea to devote the whole of Friday to the house. She would not pause, she promised herself. Chedworth would go unexplored and Hepzibah unwalked. The dog could potter around the good-sized back garden and be thankful. Even with Drew, Stephanie and Timmy there, the work would have to continue, although they had agreed there must be a visit to Drew’s property in Broad Campden at some point.

During the magical summer interlude at Farmington a great many elements had fallen into place. Dilemmas and complications had resolved themselves almost effortlessly. ‘We’ll live in the Cotswolds,’ Thea had said. ‘I’ll sell my Witney house, and you can put Maggs in charge of Peaceful Repose. I’ll work for you full time and we’ll do good business.’

‘But Maggs is having a baby,’ he’d demurred.

‘So we wait until she’s ready to work again. It’ll take a year or so, anyway, to get everything organised.’

Since then, some of the earlier difficulties had re-emerged; not least the appalled reaction from Maggs herself. Pregnancy had done nothing for her temper, which had always been short. Her association with Drew went back to a time just after Stephanie was born and the natural burial ground established. He freely acknowledged that he could not have done it without her. He owed her an impossible debt of gratitude for the support she had given him on every level, and she was not afraid to remind him of it regularly. Thea had stepped into the middle of a relationship that sometimes seemed more intimate than a marriage.

Maggs’s reaction to Thea was itself an ongoing rollercoaster. At first ferociously protective, Maggs then opted to accept that Drew was at no risk after all. But she had come to see some of Thea’s shortcomings in recent months, with the reappearance of earlier misgivings. ‘You have to be gentle with him,’ she said at one point, with a worried look. ‘And instead you just expect him to be gentle with you.’

‘Can’t we be gentle with each other?’

‘I don’t know. Can you?’

Thea had gone away with a churning sensation in her stomach. When had she ever been gentle? she asked herself. She was so often impatient, intrusive, rude, reckless. Did she have to change her entire nature in order to be worthy of Drew Slocombe?

Drew himself didn’t appear to think so, which was obviously the main thing. He showed every sign of finding her funny, independent, capable and trustworthy. It was all in the eye of the beholder, anyway, she assured herself. The Drew that Maggs knew and loved was a subtly different person from the one Thea was intending to marry. He knew what he was doing, she supposed. Everything would be fine.

As had become her habit, she phoned him at eight-thirty, after the children were in bed. She shared her observations of Richard Wilshire, the house and the shadowy glimpses she’d so far managed of Chedworth. ‘First impressions?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know. There’s something elusive about it. I know I’ve said the same about other places, but this one really does have some strange levels. I mean – there are no levels. Everything pitches at an angle. And there are two Chedworths, which doesn’t help. It took ages to find the house.’

‘Which one’s got the Roman villa?’

‘Neither. That’s off to the north, the other side of some woods.’

‘I make that three, then,’ he laughed.

‘So it is. I have a feeling there’s loads of good history attached to the place, but I won’t have time to look any of it up. Tomorrow’s going to be full on, sorting all the stuff that’s here. I can’t decide whether to start at the top and work down, or the other way round. Basically, I just have to open it all up and list what’s here. But that’ll mean moving lots of boxes and making heaps everywhere. Then I’ll have to pack it all up again, with descriptions of the contents on the top of each box or whatever.’ As she spoke, she felt a glow of anticipation at a task that would be full of interest. Who knew what she might find?

‘I think you’ll have to start in the attic, won’t you? I can’t see it working otherwise.’

‘Why?’

‘Well, if you have to put similar things together, you’ll need to bring stuff down. Or have I got that wrong?’

‘I wasn’t planning to rearrange it. Just open everything up and see what’s what. What’s in the attic can stay in the attic. I was thinking I’d leave that for when you’re here to help.’

‘But all the most interesting stuff is likely to be up there.’

‘I know. But there are spiders in the attic as well. I thought if I made a commotion downstairs, and Hepzie rampaged a bit, they might all decide to move out, before I have to face them.’

‘I see. We should probably have thought of that sooner. A spider phobia rather disqualifies you for the job in hand, don’t you think?’

‘Certainly not. I’ll just go carefully, and shake everything before I start. I can cope as long as they’re not on me. It’ll be fun, I’m sure, once I get started. I never dreamt of turning it down just for that. I need the money.’

‘Yeah.’ He sighed. ‘We’ll have to talk about money at the weekend, if we get the chance.’

‘So you can come?’

‘As far as I know, yes. Pandora’s a treasure, you know. She even offered to come here and look after the kids all weekend, so I can come to you.’

Thea’s heart jumped. ‘Wow! And what did you say?’

‘I was so surprised, I didn’t say anything definite. In a way, it would be sensible. There’s a lot of overdue paperwork in the office that she could get on with at the same time. And if there’s a removal, she could easily get Den to help with that. She can call Harriet to babysit.’

‘Harriet’s the girl down the lane, right?’

‘Right. But the trouble is, I’d have to pay Pandora properly for such a commitment. And Den’s not keen on doing removals at the moment, with the baby so new. We’re on a tightrope, in more ways than one.’

‘When were you not? It’s been the same since I’ve known you.’

‘I know. But I really think I ought to bring the kids with me and keep Pandora on standby. I don’t have to pay her at all then, unless she gets called out.’

They chatted for a few more minutes, until Drew instructed her to have an early night and face her fears with fortitude the next morning. Before obeying, she did a circuit of the house – all but the attic – trying to formulate a plan of operation. There were three bedrooms on the first floor, as well as a bathroom and a small area that might once have been called a ‘dressing room’. It was piled high with cardboard boxes. When she peeped inside one, it seemed to be full of clothes.

Downstairs there was a large front living room, and two more rooms at the back. The kitchen ran along one side of the house, light and spacious, with a high ceiling and numerous built-in cupboards of a style long ago past. A back door led out to the garden, through a sort of porch. Another door led into an outside lavatory, which showed little sign of having been updated since the 1940s.

Involuntarily, she was acquiring a picture of the old lady who had spent such a large portion of her life in this house. The picture was coloured by personal experience, namely that her own widowed mother, in her seventies, was still occupying the family home. There had been six of them in it for a long time, but it was smaller than this handsome Cotswold property. The Wilshires had apparently only managed a single child, and he had duly grown up and left at a respectable age – probably not much later than twenty or thereabouts. There had been no reference to a Mr Wilshire Senior, and scarcely any evidence of him discovered so far. All of which led to a conclusion that the woman had remained here on her own as a widow for a considerable time, free to add clutter, pursue hobbies, with never any need to throw things away. It was in no way unusual. The land was full of similar scenarios. This was not the first instance that Thea had encountered, albeit with variations on the same theme.

This woman had a variety of interests, which were already apparent from the stacks of old magazines that toppled precariously in all the downstairs rooms. Historic houses and country living were not especially surprising. But pottery and medieval French history were more unexpected. There was also a small kiln at one end of the kitchen, with two shelves of dusty equipment close by: a cutting wire with wooden handles, a collection of spatulas and some plastic bottles containing coloured slip that proved to have dried up. No clay was to be seen, and no finished products, which made Thea think it had all been abandoned a long time ago.

Soon after ten, she took Hepzie outside for her routine toileting and then led the way upstairs. The bedroom was large and handsomely furnished with mahogany wardrobe, chest of drawers and dressing table. There was an oak chest, and the headboard on the big, high bed was a semicircle of painted wood that was like nothing she had seen before. However Richard had managed to turn the mattress without assistance, she did not know.

Hepzie jumped cheerfully up, despite the height, and Thea followed a few minutes later. She felt hesitant and oddly guilty. This was another woman’s private room, the bed her own personal space for countless years. She, Thea, was a usurper, with no real right to be there. Mrs Wilshire wasn’t dead. Instead she was in a kind of limbo, the twilight of her days, no longer the same autonomous person she had been, as she waited for the end. How would that feel, Thea wondered. Surely there must be resentment, sadness, resistance, and a craving for all the familiar things that this house contained. Could anyone truly possess the maturity to go willingly into that last phase, full of clean surfaces and excessively cheerful carers? If you still had your wits about you, didn’t that make it worse? Would you have to pretend that it was all all right?

It was a very comfortable bed. Soft and deep, it offered a haven from the world. A person might live in such a bed, strewing books and biscuits across its considerable expanse. In the past, people had ‘taken to their beds’ and never got out again. It would have to be a bed such as this, to make any sense. There was something deliciously Victorian about it, and Thea felt she ought to wear a long cotton nightdress with tucks and ruches, and a flannel nightcap.

People really should be allowed to take their own mattress into the residential home, she thought. It was such a central factor in one’s life. She remembered her father’s affection for the big marital bed he and her mother had bought when they were first married. Maureen Johnstone regularly told the story of how carefully her new husband had selected the mattress and how important it had always been to him. Mrs Wilshire might well have felt the same. Perhaps her Richard had been born in this bed – almost certainly he’d been conceived in it.

She and Drew, she decided, would buy themselves a top-quality new bed, as soon as they finally came to live together.

Friday morning was there in a flash, after a fabulously good sleep. The spaniel hadn’t moved a muscle all night, the sheets and blankets had moulded themselves to Thea’s body perfectly, and her dreams had been full of contentment.

There were significant differences to this commission from the usual. Primarily, there were no animals to care for. No delicate elderly dogs or stand-offish cats. No lonely donkey or disconcerting parrot. Nothing downstairs needing food, exercise or love. Another difference was that the actual owner of the house would not be returning to assess her performance. Richard Wilshire might qualify as a replacement, but he would not have the emotional connection that his mother would. What was more, when he came back, everything would have changed. His reaction was uncertain, but Thea was determined to do a good job and earn the fee she’d been promised.

‘To work!’ she announced aloud, sliding regretfully out of the hospitable bed. Its height meant that she almost had to jump off the side, being a short person. It was a moment of nostalgia, taking her back to childhood days when she had barely managed to climb on and off her parents’ handsome bed. She was liking it here, she realised. It was bringing philosophical thoughts that while not quite joyful, certainly weren’t unduly melancholy or worrying. Mrs Wilshire had gone willingly, after all, if her son could be believed.

It was eight o’clock, and she allowed herself and the dog half an hour before the sorting began. ‘Time for a little walk,’ she said.

The house stood on a paved road, which only went a little way before morphing into a footpath – no less than the renowned Macmillan Way. The path crossed a large open field and then disappeared into a stretch of woodland. Thea let the dog run loose in the field, which undulated dramatically, showing evidence of ancient agriculture. There were no sheep or other dogs, and Hepzie ranged contentedly, nose to the ground. ‘No time to explore the woods,’ said Thea. ‘That can wait for another day.’

As they turned back, she could see part of the village, with grey roofs and stone walls that were a weathered hue of a dark beige that was one of a wide spectrum of Cotswolds colours. In some villages they were much closer to yellow than they were here. Not only did age dictate the shade, but different quarries produced stone of different shades.

Chedworth was essentially an inward-looking place, she concluded. It was not on the way to anywhere, with no large roads within earshot. The A429 was a mile or so distant from the upper end of this long-drawn-out village. There was no enticement for tourists to come here either, with the Roman villa on a quite different road. Its railway had disappeared long ago, and the little River Churn was too small to attract any river-based activities. It offered nothing for visitors, other than a farm shop and the villa. The latter made no discernible impact on the village itself, as far as Thea could tell, although she did spot a faded iron sign at knee level, suggesting that by following the Macmillan footpath, it could readily be reached. She must not fail to go for a look at some point.

But work called, and she hustled the spaniel back and closed the front door behind them. Drew had assumed that the only rational way to proceed was to start with the attic and work downwards. Certainly, the attic contained the most mysterious items, not seen for ages. But they were also liable to be dirty, dusty, broken and spider-ridden. And wouldn’t it make sense to clear some space downstairs first, before bringing stuff down to create more clutter? Richard had asked her to remove any objects that were unarguably rubbish, giving little clue as to the quantity there might be. Even as he’d been speaking, she had resolved to err on the side of caution, consigning as little as possible to the ‘to be thrown away’ pile.

She had not anticipated the emotional consequences of the job, although the previous evening she had glimpsed something of the risk. The old lady’s life was disintegrating before her eyes, as its component parts were sorted, boxed, and then stored for an indefinite time. None of them would ever be used or enjoyed by their owner again. There was a violence to it, a premature tidying away of a woman who still lived. No wonder her son felt guilty. Thea herself was aware of similar stirrings.

But she was being paid to do it, and if she gave it up, then someone else would be brought in. It would be no more ethical or sensitive to leave the house to moths and damp and rats. Now the owner was gone, the things were so much flotsam.

She went into the smaller of the two rooms at the back of the house, which had perhaps once been a sort of study or music room. It contained a substantial old bureau with a glass-fronted bookcase above it. There was also an upright piano against one wall, and two indistinct oil paintings hanging either side of it. She must get going on the first list, making an inventory of each room as she tackled it. The piano, for a start, was easy to log. She found a notepad left by Richard, and wrote ‘Broadwood piano, mahogany. Fair condition.’ Then she opened the flap of the bureau, feeling a great reluctance to examine the contents. There had been moments, during other house-sits, where she had done a spot of unauthorised snooping – opening drawers and lifting lids. But now, when it was expected of her, there was a foolish resistance.

There was nothing unduly personal to be seen. The cubbyholes were all full and in good order. A lot of chequebooks with just the stubs remaining; expired savings books and three old passports; bank statements and insurance policies. The sort of things that Mrs Wilshire’s son or solicitor would perhaps need to sift through – and really not within Thea’s remit at all. She closed it again, and turned to an inspection of the contents of the bookcase. There were two rows of hardbacks with their dust jackets still intact. They all had The Book Club printed at the base of their spines, and were novels by people such as Frank Yerby and Nevil Shute. She pulled a few out, for no good reason. Thanks to the glass doors, they were free of dust and perfectly dry.

‘This isn’t what you should be doing,’ she muttered to herself. She wasn’t being useful, inspecting items that were already in plain sight and of no great interest or value. She should be in the attic, or one of the smaller bedrooms. She should be upending boxes and emptying the wardrobes. The day would pass with nothing achieved, at this rate.

So she went upstairs and entered the second largest bedroom. Here was a big ottoman with a hinged lid, full of carefully folded cotton sheets with lavender bags tucked into the folds. Pillowcases edged with lace. Embroidered tablecloths. A silk counterpane. Lovely things that would never be used by the Wilshires again, but which might find homes if sold by specialists to those who collected such items. The ottoman itself was impressive, upholstered in red velvet and lined with satin inside. Forgetting her instructions for a while, she simply indulged in the luxury of fingering the beautiful fabrics and imagining they were hers. They conjured a special kind of affluence, where quality was taken for granted, and no self-respecting lady would wear anything other than silk next to her skin. A time quite vanished now, of course. Personal items would be made of ivory and silver, largely handcrafted. Furnishings would be embroidered by wives and daughters with long evenings at their disposal. These days, if you were rich, you paid other people to make, choose and install all your possessions. You lived in vast empty monochrome rooms and thought only about how to accumulate more wealth.

With a sigh, she took up her notepad again and started a new page. The ottoman should be listed as a piece of furniture with a value, and then its contents carefully described. It took her over an hour. When done, she finally felt she had made some progress, moving to a wardrobe with a new sense of purpose.

Here were two fur coats, several outmoded suits and dresses, and a box holding a stiff canvas hat decorated with felt flowers. Again, it was safe to assume that Mrs Wilshire would not be wanting any of these garments again.

A yap from Hepzie, waiting on the landing outside the room, drew her attention. Next came a knock on the front door, which made Thea wonder if it was a repeat of a summons she had failed to hear the first time. There was a firmness to it that suggested impatience. She went down and pulled open the door.

Two people stood there, shoulder to shoulder, one of them disconcertingly recognisable.