7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

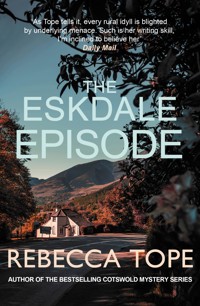

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Cotswold Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

When Thea Osborne agrees at the last minute to house-sit for Oliver Meadows as a favour to her mother, she expects a few days of peace with her spaniel, Hepzie. Uncomfortable with the news of her mother's sudden involvement with an old flame, and Thea herself unsure of how to deal with her feelings for Drew Slocombe, she hopes that some time alone in the historic town of Winchcombe will help to clear her head. But, as usual, Thea quickly finds herself at the centre of a dark mystery when she discovers a dead body in the gardens of the house.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 430

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Shadows in the Cotswolds

REBECCA TOPE

Dedicated to my long-suffering offspring-in-law – Andrea and Gareth

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Maps

Author’s Note

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Epilogue

Copyright

Author's Note

The layout of Winchcombe is very much as described in this story, but some liberties have been taken with the lower end of Vineyard Street, Castle Street and the former Silk Mill building, for which I hope I will be forgiven. The main house and all the characters are products of my imagination.

Prologue

‘Thea? Hello? It’s me.’

‘Yes, Mum, I know. Where are you? It’s an awful line.’

‘I’m in the churchyard, so I can’t shout. I know it’s dreadful of me to be using a phone here, but I wanted to talk to you.’

‘Dad’s grave?’ Thea could visualise the whole scene. ‘Have they put the stone up?’

‘That’s why I’m phoning. They did it last week – at last. You’d think they could have made the effort to get it done in time for the anniversary. As it is, they’re a month late.’

‘I can’t come and see it yet, I’m afraid.’

‘Why can’t you? What are you doing?’

The answer was too complicated for a breathy mobile conversation. ‘I’m busy,’ was all she said. Her mother would give her the benefit of any doubt, accepting her second daughter’s unpredictable lifestyle with a reasonably good grace. The knowledge that the truth was a long way from the claimed busyness made Thea feel guilty. In reality, she had very little to do for the foreseeable future. She was in fact busy being bored and depressed, with none of the traditional September sense of bracing new beginnings. The onset of autumn was not something she anticipated with any relish at all.

‘Phone me again when you get home and we’ll have a proper talk,’ she said. ‘And see if you can make your phone take a photo of the headstone. Then you can send it to me.’

Her mother snorted. ‘I can do that quite easily,’ she said. ‘Damien showed me how, ages ago.’

The second phone call came at seven that evening, after a perfect picture of her father’s memorial had come through. Its tardiness could not really be blamed on the stonemasons: the family had taken months to decide on the wording. Her father had been dead a year, and everybody still felt the loss in their own distinctive ways.

‘Me again,’ chirped her mother. ‘Did you get the photo?’

‘It’s lovely. Dad would have been very impressed.’

‘You really must go and see it. Are you off on one of your house-sitting jaunts again? It’s been a while now, hasn’t it?’

‘Five weeks. It’s not unusual to have that sort of gap. But actually – no, there’s nothing in the diary until November. I’m busy with stuff here.’

‘Decorating?’ came the hopeful reply. ‘Not before time. You neglect that poor little house.’

‘More the garden, really. I decided to give it a facelift. It’s a huge project.’

‘You know, darling, I think you need to consider finding a more reliable job. I don’t want to interfere, but really, this house-sitting isn’t going to go on for ever, is it?’

‘It suits me.’

‘I can’t imagine why. But listen … I wasn’t sure whether I should tell you this, but I do know a man in Winchcombe who’s wanting somebody to mind his house for a fortnight. Starting this weekend.’

A man in Winchcombe sounded like something her mother would never in a million years be acquainted with. ‘Who is he?’

‘Oh, that’s a long story. He’s called Meadows. Oliver Meadows.’ She said the name in a tone of familiarity, as if it had been coming to her lips daily for decades.

‘I’ve never heard of him,’ said Thea crossly. Her mother ought not to be having male friends without her knowledge. It went against the natural order of things.

‘I really know his brother, not him. Fraser, he’s called. He got in touch with me a while ago, on the email. He found me on Facebook.’ Her mother giggled complacently. ‘We had lots of nice chats, and I told him about you, and he said his brother needed a house-sitter. I wasn’t going to ask you, but somehow …’

Your tongue ran ahead of your brain, as usual, Thea thought. ‘It sounds very peculiar,’ she prevaricated, already bewildered as to which brother was which. Did she want to spend a fortnight in Winchcombe at three days’ notice? She looked to her spaniel for enlightenment. Hepzie was managing their boredom considerably better than her mistress was, and gave a small contented tail-wag.

‘It’s not in the least peculiar,’ sniffed her mother. ‘The man has a big wild garden full of birds, apparently, and wants somebody to keep up the food supplies for them. And fend off cats and things that might kill them, I suppose. He’s a photographer, so it’s not just a hobby. He does pictures of the birds for books.’

‘I hardly know Winchcombe.’ In her imagination it was a large town, very different from the little villages she normally frequented. She remembered something ecclesiastical in its history, and glimpses of medieval streets of heart-stopping beauty.

‘It’s lovely. Sudeley Castle is right there. Surely you’ve been to it? At least the gardens.’

‘I fear not. Are you sure he wants somebody at such short notice? What would he have done if you hadn’t said anything to me?’

‘I have no idea. Asked a neighbour, cut short his holiday, left the birds to fend for themselves – I don’t know. But he’s happy to pay the usual rate, and it seems as if you’re interested – despite being so busy,’ she finished sarcastically. ‘Let me give you his phone number. There’s a chance he’s already found somebody else, of course.’

Chapter One

Oliver Meadows had not found anybody else, and after a disconcertingly brief telephone conversation with him, Thea wended her way across the uplands of the eastern Cotswolds and through the heart of the region towards Winchcombe in the west, on the following Saturday morning. The weather was bright and balmy, the roads uncluttered, and the long undulations of the final miles brought to mind the endless unpredictability of the area. She was on the little road from Guiting Power that led crookedly past Sudeley Farm and then instantly into the heart of Winchcombe, which was nowhere near as large as she’d imagined, and even more beautiful.

The road narrowed impossibly as she approached the junction with the town’s main street, forcing traffic to be patient and polite as drivers took their turn to negotiate the junction. It was a steep hill up to the high street, and there was space for only one vehicle at a time, with high old buildings crowding in on either side. One was a big pub, the White Hart, she noticed. A large black car was waiting to turn down into the street, which would be impossible until Thea got out of the way. The potential for genuine logjam was plain; all it would take was one impatient driver, or a learner stalling their car on the hill. But everyone seemed cheerfully content to give way and wait for things to sort themselves out. Thea turned left, wondering just how forbearing the drivers would have been if she’d tried to go the other way. She crawled along, hoping she’d remembered Oliver’s directions accurately. The town square (which was in fact a long thin rectangle) was full of parked cars, and a white van was obstructing the way ahead. This gave Thea time to look round and try to get a feel for the place – a first impression that she knew from past experience would colour her reaction to Winchcombe from that point on.

To her right was a long featureless wall and a generous pavement. The wall reminded her of the way Snowshill Manor sat invisibly in the heart of the village behind a similar stone barrier. But here in Winchcombe there was merely the ghost of an abbey that had once been of immense importance. That much she knew from her history. Now it looked to be nothing more than a park with large trees and uninviting gates. The eye was drawn back to the buildings and relative bustle on the opposite side. As she manoeuvred around the white van, she saw Vineyard Street a short way to the left, with a sign to Sudeley Castle. That was her destination and she turned down it with a feeling of relief that at least the first hurdle had been overcome. Getting lost in the Cotswolds lanes was a perpetual faint anxiety, although in reality it had very seldom happened. The local authority was blessedly generous with signs, which helped a lot.

Vineyard Street was wide and probably lovely, if she had been able to see past the throngs of cars packed on either side. There were also trees concealing the detail of the houses. A few yards ahead was a stone bridge, just as Oliver had said, and she accomplished the final approach without mishap.

It was far from customary for Thea to feel uneasy as she approached a new house-sitting commission. And yet here she was, her head swarming with worries. The instructions told her to turn left into a disused farmyard. The house, named Thistledown, was to be found beyond the yard, with its own short track and minimal parking area. That much had come easily, but she was still tense. It had all happened too quickly, with no time to get into the right mood. Normally she had weeks or months in which to prepare for a house-sit. She would consult maps and history books and plan some walks and visits. The fact that events all too often sent such plans into oblivion was neither here nor there.

She had, for the first time, agreed to do the job without her usual preliminary visit, which she knew was risky. She was relying on her mother’s recommendation, which felt anything but solid. The tenuous link with another Meadows, whose role in her mother’s life she still did not remotely understand, was perplexing. ‘But who is he?’ she had demanded.

‘He was a boyfriend of mine, before I met your father,’ came the unsatisfactory reply.

‘But Mum – that must have been fifty years ago,’ Thea had protested.

‘Yes. Isn’t life strange? He remembers all sorts of things that I have absolutely no recollection of.’

‘And vice versa, I expect.’

‘What? Oh, I’m not sure about that. His memory seems to be a great deal better than mine.’

There was a shadow of embarrassment in the whole situation. Mothers ought not to discover long-forgotten boyfriends. It was hard to see how any good could come of it.

‘Where does he live?’

‘He’s staying with his daughter at the moment, because he’s just come back from Australia. He went there when he was thirty-five, and now he’s decided he wants to spend his final years in England.’

‘Isn’t the daughter Australian, then? Why is she here?’

Her mother had sighed noisily. ‘Why so many questions? If you must know, the wife brought the child back here, after ten years of marriage. Fraser stayed in Perth, because he liked it there and had a good job. He married again, but that wife died after only a year. So now he wants to get to know his grandchildren. Is that clear enough for you?’

Thea thought of her mother’s handsome Oxfordshire house, where she lived alone, and wondered whether this Fraser might have unwholesome designs on it. The idea of her father being replaced in the bed and chair and garden shed gave her a sharp pang. ‘Has Damien met him?’ she asked. Her brother was now the acknowledged head of the family, to whose judgements his mother and sisters all deferred.

‘He has, actually,’ said her mother shortly. ‘And you’re soon to meet his brother, aren’t you?’

She met Oliver Meadows for precisely thirty-five minutes before he departed on his urgent business. He gave her no indication as to what that business might be, and offered no contact details. Thea inwardly sighed – too many people thought it was permissable to simply disappear into the blue, and leave their long-suffering house-sitter to deal with all the unforeseen events that very often transpired the moment their backs were turned.

‘It’s quite simple,’ he said. ‘You just have to maintain the feeding programme for the birds. I’ve written it all down here, look. And I’ve made a list of places you might like to go and see.’

Instead of reading the notes, she looked at him. He was tall and slightly stooped, aged somewhere in his mid seventies, with calm, slow movements. His gaze seemed to be focused at a considerable distance, so she never felt that he saw her at all. He did, however, see her dog. Somehow, nobody had told him about the dog. ‘That’s a dog,’ he said, when she walked up to his door with the spaniel at her heels.

‘I’m afraid it is. I always bring her with me. I assumed my mother would have told you.’

‘Does it chase birds?’

It was an awkward question. The dog was a cocker spaniel, so called because they had been bred from medieval times to pursue and catch woodcock. And woodcock were birds. Hepzibah, however, had seldom displayed very much of a genetic tendency to plunge aggressively into whatever habitat the modern version of woodcock frequented. She did, however, enjoy a hearty pursuit of waterfowl. She would sometimes dive into icy waters in futile efforts to catch a mallard or moorhen. ‘Oh no,’ Thea said. ‘She’s not the least bit interested in birds.’

‘Do you give me your solemn assurance of that?’

Experience suggested that it really was best to be honest, if at all possible. ‘She’s not entirely perfect with ducks,’ she confessed. ‘But otherwise, I can promise you she’ll be no trouble at all.’

‘Ducks,’ said the man thoughtfully. ‘There aren’t any ducks. I have been thinking of putting in a small lake, but it never happened. Perhaps when I get back …’

A small lake sounded ambitious. ‘How many acres are there?’ Thea asked.

‘Four and a half. I planted all the trees myself, twenty-five years ago. It was just open ground before that.’

‘Wow!’

They were standing on a small raised patio, a few steps up from the house, looking eastwards across a densely wooded area. Apparently, the birds were in amongst the trees, which were predominately silver birch, willow, and fir – fast-growing species that gave shelter to wildlife where none had been before. ‘Come and look,’ said Oliver Meadows, with a swift glance at his watch.

The property was situated immediately to the south of Winchcombe’s main street and roughly north of the grand edifice of Sudeley Castle. A little river bordered it on one side, and a generous swathe of allotments had been established just beyond the water course. The whole area was busy on this sunny Saturday, with visitors to Sudeley’s parklands, as well as the patchwork gardens dense with beans, cabbages and pumpkins. Both sides of the road were lined with parked cars, which Thea had been forced to negotiate as she located the approach to Oliver’s house. ‘There is a better way, from the back, but it’s too complicated to explain,’ he said impatiently.

The tour of the acres was rapid and bewildering. In the middle of the woodland, quite invisible from outside, was a large hide, built from logs and thatched with bracken. Inside it had a cupboard full of peanuts, fat balls, mealworms and other food enjoyed by birds; a table; two high stools; a shelf containing binoculars and notebooks; and a large poster displaying all the finches that could be found in Britain. There was also an expensive-looking remote-controlled video camera positioned in the middle of the long viewing slit, which could swivel left and right to track birds as they visited the extensive feeding station ten feet away.

‘There’s no power out here,’ Oliver explained. ‘The camera runs on batteries. They have to be replaced every morning. So does the SD card.’

‘Is it going all the time?’

‘Ideally, yes. I don’t want to miss anything, but I can’t sit here the entire time.’

‘Of course not,’ said Thea, feeling relieved that she wasn’t expected to do so.

‘I understand that your mother would like to come and see the set-up while I’m away. I have no objection to that, so long as you take responsibility for her.’

The idea struck Thea as mildly comical, but she was careful to keep a straight face. ‘Let me show you the routines,’ he went on relentlessly, with another glance at his watch.

He took her outside and demonstrated the numerous tables, hooks, water bowls, and wire contraptions all intended to hold food for the birds. ‘Squirrels are a huge problem, of course,’ he sighed. ‘They can open almost anything, given time.’

‘I hope I don’t have to shoot them,’ she joked.

‘No, but there is a catapult in the hide, which you’re welcome to use. It does take a lot of practice, unfortunately.’

She wisely refrained from telling him that her spaniel was more than ready to chase a squirrel, given the chance. She had yet to succeed in catching one.

He led her down a little path to a sudden area of open ground, thronged with long grass and spikes of various meadow plants, long since gone to seed and stripped. It looked like almost half an acre in size. Thea could see a rickety gate at the far side. ‘This forms the boundary of my property,’ he said. ‘You can get out over there, on foot, and turn left to get into town. You come out in Castle Street, which leads into the high street. It’s a short, easy walk, if you want to pop out for some shopping.’

The tour was over in no time, and Thea suspected that they were both feeling decidedly nervous as Oliver scrambled into his car. ‘I’m sorry this has all been such a rush,’ he said. ‘If it’s any consolation, I would far rather not be going, but I haven’t any choice. The exact day of my return is uncertain, I’m afraid. It could be any time next week – but not longer than that. Your mother knows my brother, of course. If you need any help, he might be slightly better than nothing.’ He pulled a rueful face. ‘Although I suggest you do your best not to need him.’

‘I’ll be fine,’ she breezed. After all, she thought, how difficult can it be to feed the birds? Any eight-year-old could do it.

In reality, the instructions had been deplorably sketchy. She wasn’t precisely sure how to operate the camera, for one thing. Oliver had embarked on a hurried elucidation of how it worked, but then interrupted himself at the sight of a goldfinch swinging on one of the feeders. ‘Hey – she hasn’t been here for over a week!’ he rejoiced. ‘I was worrying.’ He lapsed into an enchanted silence as he watched the gaudy little bird.

‘The camera?’ Thea prompted.

‘It’s not really difficult. Don’t bother with the panning, but if you could change the cards and batteries … and label the cards with the date, maybe? I hate to miss anything, you see.’ He was whispering, his eyes firmly on the finch. ‘It is rather important,’ he added. ‘The records will lose all their purpose if there’s two weeks missing, do you see?’

‘Oh yes,’ she asserted bravely.

As a final thought, he tried to assure her that it was going to be rather a treat. ‘You can go out any time you like, of course. There’s a lot to see around here. Winchcombe has more history than almost anywhere, right here on the doorstep. And then there’s Hailes Abbey and Belas Knap and all that …’ He smiled encouragingly at her, and started the engine. As he drove off, Thea found herself struggling to feel glad to be there, with new places to explore and bird species to learn. It was easy, she insisted to herself, and there were bound to be distractions.

But the hurried arrangements began to strike her as unsettlingly irresponsible as she tried to find her way around the house, and resolve such urgent issues as what she would eat and where she would sleep. ‘Spare room, everything should be self-explanatory,’ Oliver Meadows had said carelessly, without even taking her upstairs. Although accustomed to a certain lack of formality in many of her house-sitting commissions, she found this one the most casual to date. All the man cared about were his birds, it seemed. She could neglect the house completely, so long as the feeders were full and the camera doing its job.

Why had she agreed to do it, she asked herself, as she looked round at the dusty interior? The house faced south-west, with trees to the north and east, and a downhill slope to the south. It was shaded from the sun that morning, and as far as Thea could tell, would not get very much light at any time. The windows were small in the old stone walls, and the interior felt chilly. There was no actual garden with a lawn to sit on or a sun-filled summerhouse. The patio was bare of furniture, containing nothing more than two large plant pots in which grew a bay tree and a fig, neither looking particularly robust.

The kitchen offered basic facilities in the form of a gas cooker, fridge and microwave, as well as electric kettle and toaster. It was almost as ascetic as self-catering holiday cottages used to be, with added dust on many of the surfaces.

She felt unreasonably lonely and abandoned. She had not wanted another commission, as she had tried to explain to her mother. She had been busy being bored, she admitted to herself. Bored and rather depressed, thanks to events over the summer. She was forty-four and single, with no clear idea of her future and a growing suspicion that she was not making the best of her life.

And she had no idea at all what, if anything, she should do about Drew.

Chapter Two

She was forced to go out to Winchcombe high street in order to buy some food for herself and her dog. The path at the rear of the property struck her as somewhat uninviting and vague, so she walked up Vineyard Street and out into the centre of the town, with Hepzie on the lead. She turned right and recognised the rectangular Square, dominated by a bank and a pub called the Plaisterers Arms. There was no immediate sign of a food shop, and she braced herself for the discovery that she would have to drive out to a supermarket somewhere to get bread and milk and cheese. There was, however, a butcher, which seemed to be a good start.

With sausages and bacon in her bag, she continued her exploration. Passing a small museum, she turned left into another street of shops, and paused to admire some of the window displays. As in many small Cotswold towns, there were clothes, expensive furniture, jewellery and antiques – lots and lots of antiques – to be found, and after a couple of minutes, a well-stocked Co-op which fulfilled all her basic needs and much more besides. She gave the town a mental gold star and began the return walk in a much improved frame of mind. The buildings were old and solid and lovely, with an assured sense of permanence that she found consoling. The settlement had existed for a thousand years and more, with occasional violence and trauma making its mark on history, but in essence a calmly prosperous spot, confident of its place in the scheme of things. Larger than Blockley or Chipping Campden, Winchcombe still hardly qualified as a full-sized town. Shreds of historical facts about the abbey and St Kenelm surfaced, thanks to a previous house-sit in nearby Temple Guiting, and a deepening fascination with the past. This had once been a very important place, she remembered, ten centuries ago. The abbey had been destroyed and its stone used to build Sudeley Castle and parts of the imposing St Michael’s Church. The inn had been host to countless pilgrims, and probably millions of Cotswold sheep had passed through the main street, from the Middle Ages until the nineteenth century.

These disparate facts came effortlessly to mind, almost as if she could read them in the stones. Ubiquitous helpful plaques added further information, as she strolled the length of the main street. She tied the dog to the iron gate of the church and popped in for a look, spending much of the time in front of a fabulously old embroidered altarpiece that claimed to have been wrought by Catherine of Aragon, no less. A man approached her and started telling her random facts about the building. ‘Have you seen the gargoyles?’ he asked.

‘Um … no, I don’t think so,’ she said vaguely.

‘Well, when you leave, go across the street and look up,’ he ordered her. ‘They’re really something.’

And they were. She wondered how she could have failed to notice them before she went in. She wished she had binoculars or a telephoto lens with which to inspect them more closely. Two large ones sprang from the corners of the big church porch, grotesque figures with big faces. She moved a few yards for a better view, and found the right-hand figure to be truly ghastly in its lifelike appearance. It had bulging eyes and bared teeth, with arms that appeared to be straining to push the creature out of the constraining stone and into the freedom of the open air. It had wings and a muscular chest. She stared helplessly at it, glad of her long sight that enabled her to pick out more and more detail. Furrowed brow; a suggestion of dog-like ears; a great misshapen nose. How terrifying it must have seemed, down the centuries, to anybody pausing long enough for a really good look. It would haunt the nightmares of children, and savage the conscience of a sinner. But she found herself almost liking the beast, and wishing it could succeed in releasing itself from the centuries of entrapment in the high stone wall of the church porch. It would flap cumbersomely around her head, miraculously using the small wings to keep its heavy stone body aloft …

Stop it! she ordered herself silently. Thisis ridiculous. But the gargoyle had already endeared her to Winchcombe, by adding something magical and medieval to the atmosphere.

For good measure, she gave the second gargoyle a look as well. This was more human, with a beard and a resigned expression. Deep-sunken eyes suggested sorrow, or perhaps a cosmic knowledge of the great weight of misery that was everybody’s due. ‘Thanks very much,’ Thea muttered to it and began to walk towards the town centre. The long wall of the church was adorned with more hideous faces, higher up and harder to see. One had his tongue out, and another wore a hat. Probably modelled on real people, Thea concluded.

The weather remained benign, and it was good to be in the open air. Idly, she turned back towards the Meadows house, and after dropping the bags in the hall, went out again and kept on going, heading for the large gateway into Sudeley Park. She could see dogs and children ahead, and the sense of being part of a typical English weekend was irresistible.

The way was bordered with trees, some of them immensely ancient and toweringly high. Beech, chestnut, and one or two exotic specimens she was unable to name. The sense of permanency was familiar to her. She and her former boyfriend, Phil Hollis, had noted the same feeling in Temple Guiting, something over a year before. However much the traffic might increase and people come to rely on electronic gadgetry, these trees and the houses they protected felt as if they would last for ever. The park was freely available to any who wished to feel grass beneath their feet and let their dogs run loose. Whilst a small cynical voice might suggest that all these common people were only here on sufferance, provided they behaved themselves, that was not the overall impression. Here and there a gate might be locked or a ‘Private’ sign forbid entrance, but the space was ample enough to be experienced as expansively generous.

Thea let the spaniel off the lead, and watched as she zigzagged off the path and onto the grass between the trees. An exuberant young dog on a lead held by a young woman approached, and duly abased itself before the matronly older dog. It was yellow and soft and, impossibly endearing, it squirmed and yapped in the hope of persuading Hepzibah to play. ‘What a sweet little thing!’ Thea exclaimed. ‘A golden retriever, right?’

The woman smiled, and said, ‘Right. She’s five months old.’ Thea dimly perceived a person in her early thirties, wearing a long cotton cardigan and leggings. The cardigan was a light tan colour and looked expensive. There was a halo of very fair hair above an unremarkable face. The dog was considerably more interesting and appealing than its owner.

‘She’s adorable,’ laughed Thea, bending to fondle the grinning creature. The hair was impossibly soft, the body warm and energetic. Hepzie showed a coolly polite interest, plainly perplexed as to what the attraction might be.

Thea’s spirits had been raised by the encounter, her hand still warm from the puppy’s coat. The sheer delight in life that puppies displayed always melted her heart. How wonderful the world would be if people could acquire the same approach. She smiled to herself at the absurdity of the notion. After all, even dogs had their share of pain and misery, fear and neurosis.

She thought back over the year since her father had died, during which she had undertaken several house-sitting jobs, four of them involving deeply unpleasant behaviour on the part of various people. There had been very little cause for celebration during that time. The loss of her father in itself had been a great sadness. A decent, affectionate man, he should have enjoyed at least another decade of life. Rapidly following on from his death, there had been a turbulent episode involving her sister Emily, and then, six months or so later, she had met Drew Slocombe.

And Drew Slocombe was a major part of the reason for her restless, bored, depressed, worried condition. They had become friends and partners in confronting three instances of violent death. They had found themselves in harmony, at the same time as knowing they had to maintain a proper distance between them. Because until six or seven weeks ago, Drew had had a wife.

And with Karen’s death, more than his family life had fallen apart.

It was no longer possible to phone him, or send emails or texts or even letters. His profound grief had removed him from her completely, much to Thea’s own surprise. He had phoned her to give the news, in a deceptively calm voice, and for fifteen seconds it had felt as if it could be overcome without too much difficulty. They had nothing to feel guilty about; they were balanced adults already well along the way towards a mature relationship. Drew was good and kind and funny and conscientious. He had two children and a business based entirely on principle. She approved completely of everything about him, and believed he felt the same towards her. Only after those first heady seconds did she understand that it was an infinitely great distance from being so simple.

It was silly and sad and complicated. She herself had been abruptly bereaved at a point where she had assumed she’d be married to Carl for another forty years. Drew had been amply forewarned – Karen had been ill for years. On the one hand, Thea knew that if another man had shown interest in her, barely two months after Carl died, she would not even have recognised him as human, in the midst of her stunned and anguished grief. On the other hand, she and Drew had already laid the foundations before Karen died. They had been funny together, and devious in their strategies for exposing miscreants. She had met his children and shared in some moments of danger and disaster.

And now she could not even phone or text or write to him, because all she could truthfully say was that she urgently wanted to be there for him. And she could not say that because Maggs and Stephanie and his mother-in-law and the entire female population of North Staverton were all in total agreement that this could not be allowed. He did not need Thea, they said – a rapacious and irresponsible house-sitter who consistently managed to find herself embroiled in murky murder and mayhem. No, they agreed, Drew was much, much better off without her.

So she phoned her mother instead.

‘Maureen Johnstone,’ came the reply, impressively brisk and businesslike.

‘Hello again, Mum. It’s me. I’m in Winchcombe. Thanks to you.’

‘Oh, Thea … yes. Good. Is it nice?’

‘It’s sunny, at least. Listen – have you ever actually met Oliver Meadows?’

‘No, I told you. It’s his brother who I knew. Fraser. I thought I explained.’

‘I suppose you did – sort of. But it all seems rather odd. Were you at school with the brother or something?’

‘No, no. I knew him in London, in the early sixties. He lived in Notting Hill Gate and I had a bedsit in Bayswater. He took me to Crufts.’

‘Crufts. Isn’t that in Birmingham?’

‘It is now. It used to be at Olympia. I only went that one time. I remember the poor dogs were all terribly hot.’

‘And somehow he’s found you again, after all this time. Did you say it was Facebook? I didn’t know you were on there.’

‘Well, I am. It’s great fun. I use it to keep track of Emily’s boys, mainly. You’d be amazed the things they say. I feel I know all their sins.’

‘What a modern granny! The whole thing makes me feel weak.’

‘You’re old before your time. I always said that. You were a dreadfully sensible child.’

‘And I never made a fuss about food; yes, I know, Mum. There are some people now who might tell you that’s all changed. I don’t think I was very sensible in Lower Slaughter last year, for a start.’

Her mother groaned. ‘Don’t talk about that awful time. You did your best. If only Emily …’

‘Okay.’ Thea headed her off. The topic of Emily and the events in Lower Slaughter was a taboo area within the family. After a year, it was still too raw for casual mention. ‘Oliver Meadows said you might be here with me for some of the time. Is that right? Where did he get that idea?’

‘I’m sure I told you. Fraser suggested it. He says the house is big enough for us all for a few days, and he’d like to explore the area. That’d be all right, wouldn’t it?’

‘There are only three bedrooms. One’s Oliver’s and I’m in another.’ The appalling notion of her mother and the rediscovered boyfriend sharing a bed in the third room rendered her dumb for a few moments. The woman was in her seventies, for heaven’s sake. She had sagging wrinkled skin and mottled legs. Such thoughts were probably proscribed by the demands of anti-ageism, but they were insistent, for all that.

‘Whatever are you thinking?’ her mother demanded, with a scandalised laugh. ‘Fraser can use his brother’s room, of course.’

‘Are they Scottish?’ Thea asked, registering the name for the first time.

‘What? No, I don’t think so. His accent is perfectly English. They grew up in the East End. He went to the LSE and did that PPE thing they were all doing then. Although, actually, he was a bit ahead of the crowd. Wasn’t it 1968 when all that was so fashionable?’

‘I don’t know, Mum.’ She was struggling to keep up. LSE was the London School of Economics, but she was still puzzling over PPE. ‘What’s PPE?’

‘Politics, philosophy and economics. I always thought it sounded terribly dry, but he seemed to think it was something to be proud of. He’d only just graduated when I met him.’

‘Did he have a job?’

‘Not that I can recall. He seemed to be around in the daytime a lot. I think he might have worked in a cinema – that little one in Hampstead, maybe. I can’t remember the name, but it was where they all went. It showed unusual foreign films.’

‘It all sounds like the Dark Ages to me.’

‘Yes … it does to me sometimes, as well. He seems to remember it all far better than I do. Strange as it might sound, it looks as if I made a lot more of an impression on him than he did on me. He says I was his first love and he’s never forgotten me.’

‘But you’ve forgotten him?’

‘I remember some things. He was very young and innocent. I was a bit older than him. But he did know London and showed me around. I know we did a Jack the Ripper tour, looking at all the places where the murders happened. I don’t think I’ve ever been to the East End since then.’

‘I hope you didn’t break his heart.’

‘So do I, but I have a nasty feeling I did. And it feels much worse that I can’t really remember him. I mean – he must be so hurt. Although obviously I try not to let it be too obvious.’

‘Did you keep a diary? Wouldn’t that jog your memory?’

‘I did, actually. But it just says things like “Fraser phoned again” and “Fraser here in eve” which doesn’t help much. I get the impression he was rather clingy and I had to be cruel to get rid of him. I met your father all at that same time, and wanted to be available for him. I get odd flashes of memory, but nowhere near a coherent picture.’

Thea wanted to ask Did you sleep with him? but couldn’t. Who in the world could ask their mother such a question? The answers that might come spilling out were too awful to contemplate. What if Damien, born ten months after her parents’ wedding, was somehow the offspring of this Fraser, for example? The contiguity sounded uncomfortably close. What if her mother had conferred one final sexual favour on the wretched rejected boy, a few weeks into her marriage? It struck Thea as all too dreadfully possible, as she rummaged for impressions of the promiscuous nineteen sixties. Didn’t they all sleep with everybody in those distant days?

‘And what does he want from you now? Some sort of atonement? Does he seem angry with you?’

‘Reproachful, a bit. It’s hard to explain, but I think there’s a natural human wish to relive the past. It gets stronger as you get older. It’s some kind of unfinished business for him and he thinks it should be for me as well. He wants to talk about his family and what happened after I stopped seeing him. There was another brother, quite a bit older, who took on the family business from their father. He’s been talking about that a lot lately.’

‘What was it? The business, I mean?’

Her mother laughed again. ‘You won’t believe it when I tell you. And I had no idea at the time. I’m convinced he never said a word about it.’

‘Come on, Mum. What was it?’

‘Undertakers. The Meadows family are undertakers.’

Chapter Three

But Drew’s an undertaker, she wanted to shout, as if this was a huge and unacceptable coincidence. Other people couldn’t be undertakers; that wasn’t fair. What if her mother had married Fraser, and he had gone into the family business instead of escaping to Australia? Maureen Johnstone would have been Maureen Meadows and her children would have grown up amongst coffins and pallbearers. The randomness of life, with its insistent alternative realities, was frightening.

But her mother did not know about Drew. Thea had never once mentioned his existence to her, although her daughter Jessica had met him. Jess would not have gossiped to her grandmother about him, she felt sure. She would not have known what to say, picking up on the ambivalence that Thea herself felt. For the first time, Thea understood that Jessica’s reaction to her love life was very much the same as Thea was now experiencing about her own mother. The generations repeated the pattern without even realising it. Their fathers were dead in both cases, and the painful resentful loyalty that a daughter inevitably maintained ensured that there could never be a fully acceptable replacement. Of such rigidity small tragedies were made, as well as large sacrifices. Because Drew’s young Stephanie and Timmy would be prone to exactly the same jealous adherence to the memory of their mother. The dead cast deep shadows, and there was no avoiding them.

‘So when do you think you might come?’ she asked.

‘We thought tomorrow. Late morning, probably. We can go out for lunch.’

‘Provided we don’t have to have a Sunday roast,’ Thea warned. She had eaten too many tasteless thin slices of unidentifiable meat covered in glutinous gravy to willingly risk it again. ‘I’ve yet to find a pub that makes a decent job of it.’

‘You never used to be so fussy. I blame Carl,’ said her mother lightly. It was true – Thea’s husband had been exacting in his gourmet standards. The meat had to be locally reared and killed, and the gravy made from its juices, with not a grain of Bisto. And he preferred it in chunks, not slices.

‘It’s not fussy,’ she objected. ‘It’s wanting them to serve something worth eating.’

‘We can have a salad in a garden somewhere, preferably by a river. I’m sure you can come up with the ideal spot.’

‘I’m sure I can,’ said Thea confidently. Then she had a thought. ‘But surely Fraser knows Winchcombe? He must visit his brother sometimes.’

‘He’s only been twice. Oliver is very reclusive, you see. He doesn’t encourage visitors.’

‘But he does know how to get here?’

‘Oh, yes. There’ll be no difficulty with that. He’s brilliant at that sort of thing.’

She came to the conclusion that she was more pleased than otherwise that her mother would be joining her, as the afternoon slowly waned. It was only three o’clock, and there were two hours at least before she needed to go and check Oliver’s birds. She picked up the notes he had left, and saw the lines: ‘Cleeve Common is worth a visit, for the views. Drive to Postlip Hall (left turn off the Cheltenham Road that runs past the church and out of town), park just off the road and walk up the track.’

The light outside was likely to be ideal for views, she judged. A thin layer of cloud would ensure there were no stark shadows, but a clear uniform visibility was almost guaranteed.

‘Come on, then,’ she told the spaniel. ‘Let’s start as we mean to go on. It might be raining for the rest of our time here.’

She turned left at the top of Vineyard Street and passed the church. The street was lined on both sides with an extraordinary collection of houses. No two were the same, as far as she could tell. She couldn’t recall another place, whether in the Cotswolds or anywhere else, that offered such a dazzling variety of styles, materials and sizes. It must be an architectural historian’s dream.

There was a left turn within a mile or so, and she glimpsed a sign including the words ‘Postlip Mills’ and she turned down it, assuming it was where Oliver meant. But there was nowhere to park, and it looked incongruously industrial. Notices directed deliveries and other official business matters, and the road dived rapidly downhill. ‘This isn’t right,’ she told Hepzie. ‘It’s some kind of factory, I think.’

Nervous of being stopped and interrogated, she hurriedly turned the car and went back to the main road. A second turning quickly came into view, with a sign announcing ‘Postlip Hall’.

‘Aha!’ she breathed, and turned left again.

Immediately she found a fingerpost pointing up a track to ‘Cleeve Common’. It was, apparently, half a mile distant. She and the dog could be up and back within forty-five minutes, quite easily.

They set off, the spaniel running free. The way was steep and stony, and Thea found herself considering the possibility that it had once been a significant road, bordered as it was with old stone walls. Somewhere there was a hall, invisible behind the trees on her right. Overhead, the branches met to form a green tunnel, and the path snaked enticingly upwards, renewing the sense of incipient magic that had begun with the gargoyle.

The half mile took ten minutes and left her breathless. A gate marked the sudden emergence onto the common. Hepzie had wriggled through its bars before Thea managed to open it. Ahead was an expanse of scrubby grass, and an abrupt hill boasting a scattering of vegetation that might have been gorse. There was a sign, headed ‘Cleeve Hill Common’, so badly stained with mildew that she could barely read the depressing list of regulations it contained.

She walked on, turning back every few yards in the hope of a good view of Winchcombe without having to go all the way to the top of the hill in front of her. There were trees in the way at first, but finally she got what she wanted, with the solid square-towered church clearly to be seen.

The town, evidently, was on reasonably level ground, with a considerable escarpment behind it, which after some difficulty she concluded had to be to the east, despite the fact that Winchcombe lay on the very western edge of the Cotswolds. It was not in a bowl, like Blockley or Cranham; instead it had been arranged in the valley caused by the river that she had already realised must have been important, from the number of times the word ‘mill’ appeared on street names.

The church stood protectively above the jumbled houses, like a shepherd with his sheep, she fancied. The colours were muted greens and greys, and from such a distance it was easy to perceive houses and trees as much the same in terms of their harmonious place in the picture. The town was inconspicuous, unassuming. It made no brash claims, and in the overcast light there were no unnatural flashes of sunshine on glass or metal.

It gave her an overview that she was pleased to have. However important Winchcombe might have been in the past, it was now a tucked-away little town, with no major roads passing through, no claims to power. It was clean and tidy and timeless, and it sold antiques. The woods were full of birds, and the houses were all quite effortlessly individual.

‘We like Winchcombe,’ she told the dog, which had come to her side after nosing idly in some clumps of long grass.

Later, she took the dog to the bird hide and sat watching a selection of finches picking delicately at the sunflower hearts on their feeding station. She could recognise chaffinches, both male and female, quite easily, and waited in the hope of seeing the colourful goldfinch again. Instead there were a dozen or more blue tits, and something that could only be a greenfinch. A slender little brown bird flitted amongst the branches that was neither a wren nor a sparrow, and brought Thea to an agony of self-reproach at her ignorance. The birds were certainly very entertaining, as they followed a complex dance from tree to table and back again, the little tits so quick and acrobatic amongst the bigger species. According to Oliver’s poster there should also be bullfinches and siskins, and possibly even hawfinches and redpolls. She began to grasp how exciting it could be to lure the rarer species into your garden, with the right kind of food and a careful lack of disturbance. She noticed that there were at least three distinct sorts of tits, where she had initially bundled them all under the single heading of blue tit. Hepzie lay peacefully on the rough earth floor, as her mistress indulged her new interest.

It would be even better, she guessed, in the early morning. Birds were at their most lively at dawn – weren’t they? There had to be a great many more species out there in the trees; some preferring fat and others seeking seeds. Where were the robins and wrens; thrushes and sparrows? As she mentally listed all the birds she could recall, there was a flurry at the seed table and a flash of red. When she looked properly, there was a sharp-beaked visitor with a comical red skullcap. Anybody could see it was a woodpecker, but Thea was sure she had never seen one so close up before.

It was plainly very nervous, darting rapid glances at the busy blue tits, as well as swivelling to check its back. It was almost too frightened to snatch a sunflower heart, but it remained long enough for a comprehensive inspection. Its front was a soft-looking beige, with a splash of red near the tail. The red was more suited to something much more exotic – like a parrot. Far from the more muted orangey-red of the robin, it was pure scarlet and thus surprisingly exciting. Even without the red, its black and white back was dramatic. ‘Ah,’ she breathed happily. ‘What a beauty!’

As well as the finch poster, Oliver had left a large colourful Birds of Britain book on the table in the hide. When the woodpecker had gone, she looked it up, and readily identified the ‘greater spotted’ variety. The thrill persisted for many minutes; the glimpse of the wild creature had been an unearned privilege that made her feel honoured and awakened to a world she so often forgot. Then she flipped through a section depicting small brown birds, and concluded the answer to that mystery was a willow warbler. She wasn’t at all sure she had ever heard of a willow warbler before, and certainly had had no idea what it looked like.

And she should not forget this world of British wildlife, because Carl, her husband, had been an environmentalist, fully aware of the birds of Britain, as well as the badgers and foxes and otters. She had walked with him and seen larks and swallows galore in the open fields, and coots and cormorants in the Essex marshes where they had holidayed. But they had not spent time crouched in a woodland hide watching these little things in such numbers and taking time to admire the soft breast feathers of a woodpecker.