7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

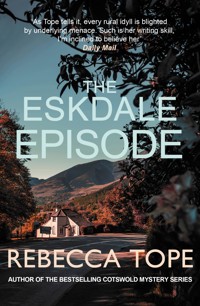

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Cotswold Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

In the wake of a series of unfortunate experiences in the Cotswolds, Thea Osborne, accompanied by her spaniel Hepzibah, is perhaps over-optimistic about the English summertime and the possibilities of her latest house-sitting assignment in the secluded village of Cranham. Despite the ease with which Thea's new job begins, looking after Harriet Young's reptiles, she soon finds a dark side to the characters she encounters. From the elderly Donny Davis to the enigmatic figure of Edwina, it soon becomes clear Harriet's beloved geckoes are not the only cold-blooded creatures at large in Cranham...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 439

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Deception in the Cotswolds

REBECCA TOPE

In fondest memory of Martha Grutchfield.

Contents

Title PageDedicationMapsAuthor’s NoteChapter OneChapter TwoChapter ThreeChapter FourChapter FiveChapter SixChapter SevenChapter EightChapter NineChapter TenChapter ElevenChapter TwelveChapter ThirteenChapter FourteenChapter FifteenChapter SixteenChapter SeventeenChapter EighteenChapter NineteenChapter TwentyBy Rebecca TopeCopyright

Author’s Note

As in other titles in this series, the story is set in a real Cotswold village. Cranham is much as described, including the pub, and the ‘mushroom yews’ in the churchyard. However, the Manor and other individual houses, as well as the people, are all products of my imagination.

Chapter One

Light was streaming into the entrance hall as Thea walked in. Her spaniel’s claws clicked on the polished wooden flooring, and the scent of beeswax brought with it associations of affluence and solid English stability. Hollywell Manor, in the village of Cranham, was to be their home for the next two weeks, and the weather seemed set fair. Cranham was – she hoped – an undiscovered gem of the western Cotswolds, and the house-sitting responsibilities a lot less onerous than usual. Despite a lurking sense of caution, Thea felt optimistic and light-hearted.

The month of June was about to begin, with all the usual mixed feelings that accompanied the start of an English summer. A cold wet June was a loss that could never quite be compensated for by July and August, however lovely they might turn out to be. A flaming heatwave in June, however, could bring with it a surge of Continental well-being, a pretence that real summers could happen, even here on the north-western corner of Europe where the Atlantic troughs habitually held sway through much of the year. Weather, thought Thea, became increasingly important the older you got. Or perhaps it was just her – spending so much time outdoors, often involved with livestock and at the mercy of the elements.

The Manor was approached up a steepish drive, the entrance to which had been difficult to locate in the confusing lanes. ‘There’s a Lodge,’ Harriet had told her, when she had made her preliminary visit a month earlier. ‘You can’t miss it.’ It wasn’t the property itself she missed, but the entire section of the village in which it sat. Twice she had failed to take the required turning, dismissing it as too insignificant to be the one she wanted.

But she got there eventually, to be welcomed by Harriet and given a comprehensive tour of the house and a list of her duties. The Manor, it turned out, was something of a fraud. Built of the ubiquitous honey-and-cream Cotswold stone, which had faded to an unpretentious pale yellowy-grey, it had never actually been the manor house in the parish. Harriet Young, the owner, had manifested some irritation at Thea’s questions as to its history. ‘Oh, I think it was built around 1860,’ she had said, with a challenging look that added, Isn’t that old enough for you? Harriet was American. To her, 1860 was pretty much as old as anything got. When Thea hurriedly expressed her profound and genuine admiration for the proportions, furnishings and situation, Harriet had been mollified. ‘It’s completely unchanged,’ she insisted. ‘No additions or alterations since the day it was built.’ She indicated the oak panelling, the boxed-in staircase, the first-floor gallery, all of which Thea thought wonderful. Outside, Harriet pointed out the impressive pair of wrought-iron gates at the foot of the long drive. ‘They were done by hand,’ she said proudly. ‘The letters from the owner to the blacksmith still exist.’

Thea had not, on that initial exploratory visit, properly calculated the size of the house, but it clearly had space for a large family with numerous servants. The fact that Harriet Young lived there alone was so outrageous that Thea found it almost funny.

But she was not entirely alone. There was a capacious cellar, which was home to dozens of creatures, living in tanks full of greenery and difficult to discover amongst the leaves and stems. ‘They’re geckoes,’ Harriet had explained. ‘I breed them for pets. You’d be surprised how many people keep them.’ She had fished out an example, and let it walk onto Thea’s hand. It clung with bulbous fingers, pressing coolly into her flesh, rolling prominent eyes at her. The light-brown skin was matt and rather beautiful.

‘Breed?’ she queried. ‘How?’

‘They lay eggs, which I take away and incubate for them. It’s an extremely precise science. Everything has to be just right. And of course, this climate’s completely wrong.’

Thea took a step back. ‘Whoa!’ she protested. ‘I’m not qualified for anything like that.’

Blithely, Harriet had assured her that it was easy, and there would be no recriminations if things went wrong. ‘But why,’ asked Thea, ‘don’t you get somebody who knows what they’re doing?’

Something in the woman’s face hinted at the answer. Her eyelids lowered, and she avoided Thea’s gaze. ‘Well, I’m not entirely orthodox,’ she admitted. ‘It’s still a bit of an experiment, you see. If I got involved in it professionally, I’d be in for a whole host of regulations and restrictions. As far as you’re concerned, they’re just a few pets living in the basement – OK?’

Thea had no qualms about regulations, but she still worried about letting the wretched creatures fall ill or die under her care. ‘Well …’ she had prevaricated, already knowing that the village, the house and the time of year would suffice to persuade her to take the commission ‘… so long as I won’t be liable for any disasters.’

‘You’re insured, are you?’

‘Absolutely not,’ laughed Thea. ‘I agree with you that the less paperwork the better, in all areas of life. Why – you don’t think I should be, do you?’

‘Not if you don’t. I’ll trust you if you’ll trust me. Nobody sues, whatever happens. Right?’ Harriet heaved a long sigh. ‘That’s one of the main reasons I left the States, you know. Everything you do runs the risk of some sort of litigation.’

‘It’s getting as bad here,’ Thea told her. ‘You’ll have to move to somewhere like Greece or Mongolia next.’

‘At least that’d suit the geckoes,’ Harriet had smiled. ‘Oh, and there’s Donny to consider as well,’ she’d plunged on. ‘You’ll need to understand about Donny.’

She had understood only too well – or thought she did. Donny was seventy-nine, and suffering from a distressing collection of ailments which prevented him from driving or walking very far. He lived in the former Lodge of Harriet’s large house, under the official care of his daughter, Jemima. ‘And he has a lady friend, Edwina,’ Harriet had added. ‘But she’s away at the moment. They’re very close friends, but she doesn’t live with him.’

Donny, it seemed, had developed the habit of visiting the Manor most afternoons as part of an exercise regime his womenfolk had ordained for him. It would be incumbent on Thea to make him a drink and let him talk for half an hour before launching him down the drive on his tottering journey home. ‘It is a bit restricting, I’m afraid,’ said Harriet.

Thea had found the balance of pros and cons rather more even after that particular disclosure. ‘Anything else?’ she had asked warily. ‘You don’t mind me bringing my dog, do you?’

‘Your dog is adorable,’ Harriet gushed. ‘It’ll all be fine, trust me. And I promise you the weather’s going to stay perfect the whole time you’re here.’

The well-designed house compensated for everything. Cleverly positioned on a south-west-facing slope, with views across one part of the village, including the square church tower and beyond to the sprawling beech woodland, it was exactly right in all particulars. Thick walls, with window seats in the main rooms as a result; old flagstones on the kitchen floor; good-quality carpets upstairs – she recognised that it had been built by an Arts and Crafts aficionado along medieval lines as far as the basic structure went. The overlaid Victorian elements gave it the best of both worlds, despite the concerns that purists might have as to its hybrid character. How on earth did Harriet afford it, Thea wondered, without having presumed to ask the question aloud. The American appeared to be in her fifties and without visible means of support, if she was at home every afternoon to receive Donny. Even if the Manor was a fake, it was still a property of very considerable value. And it was fabulously comfortable. The hot water worked effortlessly, which even in June was a high priority, and the sitting room was a joy to relax in. Hepzibah, the cocker spaniel, found a favoured corner on the two-seater sofa, moulting gently as she turned round to get herself more comfortable. ‘I can brush the hairs off on my last day,’ Thea told herself, ever mindful of the inevitable mess her dog caused in other people’s houses.

Harriet had gone to Lindisfarne for two weeks’ retreat. There was no conceivable reason to contact her, she insisted. In fact, she would like to place a total veto on doing so. ‘That’s another reason for hiring you,’ she said, obscurely. ‘If I’d gone through some stupid agency, they’d have forced me to leave a number.’

Thea closed her eyes in a silent prayer, and wondered again about such extraordinary levels of trustfulness.

The first afternoon was spent in assessing food supplies, examining a large-scale map of the area and pondering the possibilities of Cranham’s single pub. Routines were minimal where house-sitting was concerned, but this, her ninth commission, could hardly fail to fall into something like a familiar pattern. None of her friends or relations had undertaken to visit her, but she supposed she might tempt one or other to come over for an evening or weekend. She had been disappointed to realise that she had just missed the famous Coopers Hill cheese-rolling race, which had been a local tradition for centuries. Even though the authorities had tried to cancel it in recent years, because of the dangerously large crowds, some hundred of determined stalwarts kept it going. It had taken place the previous Monday and sounded like a highly entertaining day out, watching people of all ages launch themselves down a near-vertical grass slope.

But there were plenty of other attractions: Painswick was close by, an obvious destination for a long country walk. Slad, made famous by Laurie Lee, was further on, in the same direction but in another valley.

The dog itself forced certain absolutes into place. She had to be walked, preferably along pathways free from traffic and sensitive farmers. Woodland was ideal – something Cranham possessed in abundance. The settlement was in a deep natural bowl, far from busy thoroughfares, its little approach road continuing aimlessly on to join another road scarcely larger. The landscape altered rapidly to the north, where it swept upwards in a dramatic lift. Any sense of direction became unreliable in the village itself, where points of reference disappeared amongst high hedges and wooded hollows.

The evening was as long and golden as anyone could wish for. Harriet Young’s garden was disappointing by Cotswold standards, but it managed to provide a patch of healthy lawn, and a magnolia which had just dropped the last of its blooms. For herself, Thea would have planted a lot more shrubs and small trees to fill some of the oddly naked areas that made the house seem unduly exposed. A closer inspection revealed that substantial trees had been cut down in recent times, their stumps still visible. Inwardly tutting at the vandalism, she arranged herself comfortably along a hardwood bench, and let the slowly descending sun illuminate the book she was reading. Hepzie left the cosy sofa indoors and flopped contentedly onto the patch of shade beneath the bench cast by her mistress.

‘This is the life,’ said Thea.

Next morning, her first glimpse of the sky from her bed brought sharp disappointment. It was altogether the wrong colour: dove-grey when she had expected forget-me-not blue. A thick blanket of cloud spread from east to west without interruption. A sense of outraged betrayal gripped her, as she realised it wasn’t just cloudy, but actually raining in a fine drizzle that more closely suited February than June.

The geckoes in the cellar were invisible, as before. Thea checked the temperature gauge and humidity monitor, then she peered at the dozen or so eggs in the incubator. Harriet had said that there was a slight chance that one or two would hatch, but it was very unlikely. ‘Just leave them, if that happens,’ she instructed. ‘I don’t think they’ll want to go anywhere for a few days.’

The walls had been painted brilliant white, with a large mirror to catch all available light from the small window high in the south wall. It was the antithesis of a classic cellar with the expected cobwebs and shadowy corners, but it still carried the aura of isolation and strangeness that came with underground rooms. It was low-ceilinged, approached by a flight of stairs from the kitchen, and the floor was rough stone. A faint smell of drains was discernible. In the early years of the house’s history it would have been used to store wine, perhaps, and cheese. At first Thea had assumed it might also have housed the coal used to heat the many rooms, but she had found a more obvious coal-hole on the other side of the building during her initial explorations.

Breeding geckoes seemed a very peculiar activity, when she thought about it. The poor things had a dull existence in their restricted tanks. Harriet had manifested little affection for them – she had not given them little treats or cooed sweet nothings at them. If all the eggs hatched, surely they would earn far less than had been spent on refurbishing the cellar. How many hundreds would have to be sold in order to realise enough for even a modest income? Of course, people did pursue strange hobbies of this sort. Thea had encountered a number of weird pets since she began the house-sitting. One of the main reasons for employing her had almost always been to take care of livestock, indoors and out. A parrot, donkey, ponies, cats, dogs, rabbits – she had managed them all with varying degrees of success.

It was mid morning, and the drizzle persisted. The sun-filled bowl that had been Cranham the previous day was now a dark and unappealing trap. What would it be like in winter, wondered Thea. If the roads were icy, it would be hard to escape up the steep hills. If it snowed heavily, the whole place might disappear completely. Torrential rain must surely fill the main street with running water that would threaten many of the houses.

To make matters worse, it was a Sunday – a day when one might justifiably plan long rambles or lazy days in a sunny garden. Irritably, Thea made herself an early lunch and considered activating her laptop for some time-killing games of Scrabble with strangers from foreign lands. It was something she had been doing on and off for the past two years and more, and which maintained its sporadic appeal when life turned dull and aimless as it had that day. An hour or two passed with the help of the radio and the computer, but the sky showed no sign of lightening.

She saw the old man approaching some minutes before he reached the front door. His head, with its covering of floppy white hair, was unprotected from the rain, and he wore no jacket or raincoat. It was as if the weather made no impression on him at all.

‘You must be Donny,’ she greeted him, when he finally arrived. ‘I’m Thea Osborne and this is Hepzibah.’

‘Yes,’ he agreed with a nod. His shoulders were narrow and slumped, his legs spindly inside the cotton trousers. A constant tremor kept his whole body moving as if he were shivering in a cold wind. His eyes were a faded brown, peering through lids that seemed to lack the energy to open properly. Stubble covered much of the lower half of his face, suggesting four or five days without a shave. But there was a vitality to him that Thea recognised instantly. This was a man who made things happen, and didn’t wait for life to come to him. Wasn’t he here on a drizzly Sunday, ready to meet somebody new and take his chances with her, rather than huddling in his little house watching inanities on the television?

‘Cup of tea?’ she suggested.

‘Coffee,’ he corrected, with a hint of reproach, as if she should have known his preference. ‘Black, no sugar.’

He followed her into the kitchen and sat at the table watching as she hunted for a mug and teaspoon. ‘The blue one’s mine,’ he said, in his light piping voice.

She gave him a look. ‘Is instant all right?’

‘Perfectly, thank you.’

The kitchen had fewer modern gadgets than many Thea had experienced. Harriet Young was pleasantly normal in that respect, it seemed. A faintly grubby microwave sat on one counter, near a large wooden bread bin. The fridge-freezer was stuffed with anonymous bags and trays of assorted meat, bread, ice cream and vegetables. The top of it, too high for Thea to reach, was piled with dusty-looking cookery books and a fat half-used candle. Fruit for the geckoes was in a special plastic box, with some dried insects that looked like raisins.

‘Managing, then, are you?’ Donny asked.

‘So far. It’s not very difficult, really, although I’d banked on decent weather. I’m trying not to worry about the geckoes.’

‘Silly things,’ he smiled, his head quivering in the perpetual tremor. ‘Don’t know what she was thinking of.’

‘Oh well. They’re quite sweet, I suppose.’

He waved the topic away, and cautiously sipped the coffee, holding the mug tightly in both hands. It was a tense business, and Thea realised she should have made sure it wasn’t filled too close to the brim.

‘Never get old, not if you can help it,’ he said, having managed a swallow of the hot drink. ‘It’s a miserable business.’

‘Not much choice, is there?’ She sat down opposite him and tried to concentrate. Would she really get old one day, like this man? Like everybody, more or less. ‘I suppose it’s better than dying young.’

He shrugged. ‘My daughter died last year. She was forty-one.’

‘Oh gosh! I am sorry. My husband died three years ago. He was forty-two.’

He closed his eyes. ‘Forty-two,’ he murmured, as if it hurt. ‘That’s another one dying too young. Was he ill?’

‘No. Car accident. Was your daughter? Ill, I mean.’

‘Oh yes. Had a bad heart all her life. They did a transplant and she died.’

They did a transplant and she died. Thea heard a whole anguished story in that little sentence. ‘Right away?’ she asked, too horrified to mince her words.

‘Eighteen months after the operation,’ he said. ‘You should have seen her.’ Again he closed his eyes. ‘It should never have been allowed. They think they’re so clever, but there are things they never even stop to consider.’

How did we get into this so quickly? Thea wondered. It was as if Donny needed to unburden himself of this enormous trauma before they could settle into a normal discussion of the weather or the next general election.

‘Such as?’ she prompted.

His eyes opened fractionally wider, to reveal a rage undimmed by his own physical failings. ‘Such as, how is a person supposed to live with somebody else’s heart inside them? They just laughed it off as fanciful when she said she didn’t feel as if she was herself any more. She would hold herself …’ he clasped his own mottled hands over his chest ‘… and say she could feel the person’s life thumping away, trying to escape.’

‘Sounds a bit … well, oversensitive,’ Thea suggested with a smile. ‘Although I can see it must feel terribly strange, especially at first.’

‘That was her nature, taking everything hard. She’d always been like that.’

‘And I suppose she would have died young, without the new heart?’

‘So they told us.’

‘You didn’t believe them?’

‘She’d never have managed a baby, or climbed Mount Everest, or run a marathon. But if she looked after herself, and kept herself quiet, she’d have lived more than the time she did. And she’d have been easy in her mind. They break the ribs, you know, to get at the heart. For a woman …’ his eyes lost focus, filmed with tears ‘… well, she was dreadfully scarred. Like cutting up a piece of meat.’

Too much information, Thea thought, with a wince. But it was all true, as far as she understood the procedure, and it chimed with the occasional fleeting notions she had entertained on the subject. Could she ever be so utterly desperate to live that she would permit such drastic medical interference for herself? Did everybody cling to the hope of continuing life so passionately that they were willing to pay such a price when it came to the crunch?

‘I’ve made a living will,’ he said, conversationally. ‘So I won’t fall into their clutches.’

‘Oh?’ She had heard the phrase before without being entirely sure what it meant. ‘How does that work?’

‘They’re to leave me to die,’ he said fiercely. ‘That’s what it means.’

‘Oh,’ said Thea again, a jumble of conflicting thoughts all clashing together in her head. ‘But … I mean, are they allowed to do that?’

His bravado evaporated. ‘It depends,’ he said.

‘They mean well, you know,’ she said feebly. ‘Palliative care and all that. Lots of people say it’s really nice in a hospice, if you can get a place in one. Everybody being so honest and open, and making every minute count.’ She smiled tentatively. ‘That sort of thing.’

‘I’d never get a hospice bed. They give them all to people with cancer. That’s about the only thing I haven’t got. I’m just supposed to slowly crumble away, until I can’t control any of my bodily functions.’

He breathed heavily for a few seconds, and then drained the coffee with difficulty. Thea had no choice but to hear and understand what he was telling her. No platitudes would help him, nothing she could say would change the reality. Pity flooded through her, and a surging desire to help. She reached for his quivering hand. ‘Don’t think about it,’ she advised, earnestly. ‘I know it sounds pathetic, but you’re here now, chatting to me, and it’s OK this moment, isn’t it? That’s all that matters. You don’t know what’s going to happen. We can’t plan our own deaths, you know. You could drop down dead now, with a stroke or something, and all this worrying will have been for nothing.’ She smiled into his eyes. ‘And you look to me like a man who enjoys life.’

Again, the film of tears sluiced his eyes. ‘I knew you were a good ’un, soon as I saw you,’ he said faintly. ‘It’s a rare thing, for a woman to talk so frankly as you just have. I just wish Mimm would listen to me sometimes. She’s always in such a tizz, she can’t stop long enough to hear what I’m trying to say.’ He was mumbling, forcing the words through a wash of emotion.

‘Mimm?’

‘Jemima. My daughter,’ he elaborated, rubbing his midriff. ‘It’s not such a good day, today, to tell you the truth. Too many aches and pains.’ He fingered his stubbly chin. ‘And I ought to get myself a shave as soon as Weena comes back.’

Thea refrained from questioning this second odd name. Edwina! she remembered. His lady friend. ‘Doesn’t your daughter do it?’ she asked.

He snorted. ‘I won’t let her. Far too ham-fisted, she is. I’d lose half my skin.’

Thea winced in sympathy, hoping there was no requirement for her to volunteer to do it. Donny went on, ‘I miss Weena when she goes off. She’s always very good to me, even if we do have our disagreements. She means well, nobody can deny that.’

Hepzie, noticing her mistress’s solicitude, decided to join in. She approached the old man and pawed gently at his leg. He looked down and smiled at the large liquid eyes and floppy black ears. Automatically he reached down and fondled the soft head. ‘It might be different if I had a dog,’ he murmured. ‘Something to live for, that would be. You can’t let them down, can you?’

‘Have you ever had one?’

‘Once. We had a little Westie when we were first married. He got run over and my wife said she couldn’t bear another one, knowing it would die one day. Silly, really. Same with Mimm. She’s like her mother, though she won’t hear of it if I say so.’

Thea recognised a feeling of mutual understanding that went beyond the brief verbal exchanges on this first encounter. Rightly or wrongly, she thought she understood this old man, his wishes and fears, priorities and prejudices. She could hear a lot of his thoughts between the words, and even thought she grasped some of the essence of his daughter as well.

He sat quietly for a few minutes, mastering his emotions, then he gathered himself and got to his feet. ‘Thank you, my dear. I’ll be going now.’

He straightened slowly, and turned for the door. A final thought detained him. ‘But you’re not right altogether, for all that,’ he said, without meeting her eye. ‘One thing’s sure – I will end up dead. And I need to get the funeral sorted out. Mimm has some plan for putting me and Janet together in the churchyard, but I’m not sure that’s what I want. She won’t let me talk about it, you see.’ He gave her a searching look. ‘Have you any suggestions as to how I might go about fixing that?’

‘As a matter of fact, I have,’ she said. ‘I know the very man to help you.’ And she detained him on the threshold for another ten minutes while she explained all about her friend Drew Slocombe and his alternative burial ground.

Chapter Two

She phoned Drew soon after Donny had left, and explained the situation. ‘I’ve no idea how much time he’s got, or what he can afford. I only just met him this afternoon. But I thought you could maybe send a leaflet or something, and he could contact you,’ she said carefully.

‘But … will he want to be brought down here, away from where he lives?’

It had been over two months since she had heard his voice, but it was as if they’d been speaking every day. Dimly she noted that she had established an almost instant friendship with Drew, much as she had with Donny. It made her feel slightly complacent, the way she could simply take up the threads again, despite not having seen or spoken to Drew for so long. Preliminaries had been minimal – she could hear everything she needed to know in his easy response to her initial words.

‘What about the Broad Campden field? Is that going ahead?’

He sighed loudly. ‘Extremely slowly. Your man would have to live the best part of another year at this rate to stand any chance of a grave there. But at least it’s still under discussion, and I’ve completed a large mountain of paperwork for the planning committee.’

‘Oh. Well, I should think he might manage that. He’s still walking, and feeding himself. I don’t know what his prognosis is. I don’t even know what the matter is, except it looks like Parkinson’s.’

‘Poor chap. And you’ve only just met him, did you say?’

She gave a self-deprecating snort. ‘I know. Seems crazy, doesn’t it? But we just seemed to hit it off from the first moment. He had no intention of settling for small talk. Just plunged in with the serious stuff.’

‘He’s lucky.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, to find you. Nobody but you would have let him talk about his own grave after five minutes’ acquaintance.’

‘Rubbish. You would. And your Maggs person.’

‘That’s different. It’s our job.’

‘He wanted to talk about it. He asked if I could give him some help with his funeral, a minute before he left, and I told him what you did, in a fairly general sort of way. So where do we go from here?’

‘As it happens, I’m coming up on Tuesday, to see the legal people. I might be able to drop in and talk it over with him. Where are you?’

‘Cranham. It’s on the western edge of the Cotswolds, down a maze of little roads. Have you got a map? But let me check with him first and call you back. It’ll be this time tomorrow, I expect. He comes every afternoon, so we could easily fix something up for Tuesday.’

‘OK. I can probably find it. If this is to be the first customer in the new cemetery, it’s worth getting a bit lost.’

‘Good,’ she said vaguely, thinking it would be nice to see him again.

‘Thanks, Thea,’ he said warmly. ‘I appreciate you thinking of me.’

‘Don’t mention it,’ she said.

She took Hepzie around the village at five, when the drizzle finally gave up and a late sun emerged to brighten the evening. It shone warmly on the damp hedgerows and verges, creating a steamy humidity that felt quite foreign. She had no real feel for Cranham yet. The only resident she had met was poor old Donny. She passed quiet stone houses with flower-filled gardens and no signs of life. It was no different from many other Cotswold villages she had experienced in that respect. A few cars passed by, containing the first of the trickle of people coming home from a day out – some probably even worked on a Sunday. Once back, they seemed to disappear out of sight, regardless of the weather. Long summer evenings were no more effective at tempting them onto their front lawns than a November downpour would have been. Occasional voices floated from back gardens, where privacy was guaranteed by walls and fences and hedges.

But there were a few people in the woods when Thea and Hepzie turned off the road and passed the unusual community playground which the locals had evidently established for their children. This, she remembered, was the last weekend of the half-term holiday. School would begin again the next day, with whatever small snatches of freedom modern children enjoyed curtailed for another six or seven weeks. There were two girls sitting on top of a sturdy climbing frame, talking intensely, heads close together. A man with a large grey poodle approached her. He wore a blue Breton cap with a wide brim over his face, and a lilac-coloured shirt. He had shapely, fleshy lips, reminiscent of the figures in many a Pre-Raphaelite painting. The only gay in the village, flashed through Thea’s mind, and she gave him a warm smile, prompted largely by inner amusement at the inevitable reference. He smiled back, and stopped walking.

‘Nice little spaniel,’ he observed. The poodle was ignoring Hepzie completely, its sharp nose averted.

‘Thanks.’

They watched the dogs in silence for a moment, pausing before the inevitably continued conversation. The balance had been tipped the moment the man halted and spoke. And yet there remained the traditional British reluctance to engage with a stranger.

‘Haven’t seen you around before,’ he said.

‘No. I’m house-sitting for Harriet Young, at Hollywell.’ She waved towards the Manor.

‘Are you indeed? Well done you. Fabulous house, of course. Full of good things. I like good things. And hasn’t she got some kind of reptile in the cellar?’

Thea smiled again at the image of a massive iguana lurking in the shadows that the words evoked. ‘A few, yes. Only little ones.’

‘And you’ll have to suffer the miserable Donny Davis as well, I imagine?’

‘He drops in. I don’t find him at all miserable. I rather like him.’ She sounded stiff, even to her own ears.

‘People do, at first. He’ll soon drive you crazy with his self-pity.’ He raised his eyes to the sky. ‘Please let me die,’ he quoted, in Donny’s quavering tones. He looked hard at Thea then. ‘Why doesn’t he just find the guts to put an end to his misery, and do us all a favour, if he’s so adamant that he won’t let a doctor look at him?’

Thea was shocked. ‘He enjoys life too much, I suppose. It’s not so easy to just kill yourself because it might be convenient to your family. And I imagine he’s within his rights to stay away from doctors and hospitals after the dreadful time he had with his daughter.’

‘If you ask me, it’s a sign of dementia. And you’re wrong about dying – it’s as easy as pie. It’s staying alive that’s difficult.’ He gave her a straight look. ‘I should know.’

The man was in his late thirties, she estimated. Probably quite affluent and apparently in good health. He obviously had no idea what he was talking about, despite his claim. Her mouth felt full of arguments, jumbled assertions about fear of death, and essential human ambivalence, and a burning need to leave some sort of trace behind.

‘Oh,’ she challenged. ‘Why’s that, then?’

‘As it happens, I’m a doctor myself. Cardiovascular surgery, to be exact.’

Thea gulped back her astonishment. ‘Fancy that,’ she managed. ‘I would never have guessed. But I stick to my point. I still don’t think you understand about Donny. You probably have to be old and ill to have any hope of getting inside his head.’

He held her gaze. ‘But you’re neither, and you seem to be claiming some special insight.’

She quailed for a moment at his refusal to give way. ‘At least I’ve been listening to him,’ she blustered.

The man shrugged elaborately. ‘Well, I don’t mind telling you I head for the hills if I see him coming my way. Jasper and I know a few nooks and crannies in these woods, if we need to make an escape.’

‘I wouldn’t worry,’ she flashed, determined not to be intimidated by him. ‘Donny’s not very fast on his feet, after all. I wouldn’t think there’s much risk of him catching you.’

‘Ooh—’ even before he finished his remark, she had found herself registering this outrageous parody of Kenneth Williams ‘—listen to you! Here for five minutes and already knows all about it, am I right? Well, Madam House-sitter, you’ll learn. Come back to me in a week and tell me I was right. You will, you know. My name’s Philippe, by the way. What’s yours?’

She told him, but neglected to introduce her dog, as she normally would. This Philippe was quite frivolous enough for both of them, and if that made her seem stiff by comparison, then so be it.

‘Have fun, then, Thea Osborne,’ he said, and continued on his way.

She released the spaniel from the lead and wandered slowly along the woodland paths, one eye on the plumy white tail that bobbed amongst the holly and brambles beneath the big beech trees. Cranham was still quite unknown to her after a busy twenty-four hours. Part of her hoped to keep it that way, staying quietly at Hollywell Manor, making coffee for Donny and catching whatever sunshine there might be on offer. A year earlier she had been at Temple Guiting in a blazing hot spell, with Detective Superintendent Phil Hollis. Now a new Philip – she would have been happy to bet that was his original name before he Frenchified it – had crossed her path, albeit highly unlikely to find himself in anything like the same kind of relationship to her as Hollis had been. Now firmly in the past, she preferred not to think about him and the perverse way she had treated him. Since then, men had been in short supply in her life.

Except for Drew Slocombe, of course. And Drew didn’t really count.

The evening wound down slowly, still light at half past nine, albeit cloudy. The gecko eggs slumbered peacefully, their heedless parents marginally more active when Thea went to inspect them. She caught the quick movement of one, at the top of its tank, just before it froze halfway behind a large palmate leaf, the clever camouflage unsuccessful once she had seen it move. Where did geckoes come from, she wondered. How long did they live? She had blurry memories of reading about them sitting above windows inside houses in hot climes, waiting for flies to come their way. A sort of tropical version of Dickens’ cricket on the hearth; something people regarded as benign, even rather auspicious. But quite how it evolved from there to a British craze for owning them as pets was obscure. As far as she could see, they were singularly unrewarding.

She thought about Donny, bracketing him with the geckoes as another element of her responsibilities. Would he appreciate her introducing him to Drew, forcing him to confront the reality of his own grave? She acknowledged that the poodle-owning Philippe had already sown a few seeds of doubt, despite her indignation at his attitude. But she clung to the idea that arranging a meeting between Drew and Donny would be an interesting experiment for both men – even possibly therapeutic for Donny if Drew could manage to be as sensitive and understanding as she believed him to be. If the old man backed off, muttering that he really wasn’t quite ready for anything so concrete, then he might relax into enjoying the summer and forgetting about his bleak future.

Except he had already seemed pretty relaxed. Thea’s first impression of him as a man who relished life felt rock solid. She would never have charged him with self-pity, despite the terrible story about his daughter, and his own limitations, and Philippe’s unfeeling accusations. With difficulty she recalled what Harriet had told her. There was a lady friend called Edwina. Why hadn’t she, or the daughter, not helped to settle the matter of his funeral already? Did they refuse to discuss anything to do with death and dying, as many people did? Were they relentlessly, mindlessly, jolly when all the poor man wanted was to clarify the arrangements for something that was sure to happen eventually? Did they laugh it all away and change the subject? What did they think about the living will and its implication that Donny would wish to die at home, with their full cooperation? Had he perhaps gone so far as to appeal to them for assistance in committing suicide, when he felt the time had come, only to meet with frozen faces and a determined change of subject?

The questions came and went, the answers all pending further contact with the man himself. Thea found them absorbing, in a way she had not felt absorbed for some time past. Death had touched her many times in the last three years, until it seemed it was following her around, stalking her like a persistent admirer. Repeatedly she had promised herself that it would not happen again, only to be foiled. And now, here it was again in a different guise, intriguing in a new way. A man who both did and did not want to die, who did and did not want to live. It felt like being shown a window onto something rare and vital, where she might be able to contribute, thanks to her ability to face up to more reality than most people could.

She went to bed, eagerly looking forward to her next encounter with the sick old man.

Chapter Three

Next morning, she was awake at eight, after a solid nine hours’ sleep. Hepzie stirred lazily when her mistress threw back the light duvet and went to look out of the window. Her room was next to the main bedroom, both of them overlooking the front garden. The Manor boasted no fewer than five bedrooms, as well as an attic where servants had once slept.

Outside, a middle-aged woman was blithely cutting roses from the bushes which grew along the inside of the hedge. She carried an old-fashioned trug on her arm, and wore a long cotton skirt. ‘Good God, it’s a ghost,’ Thea muttered. The fact that the spaniel had given no hint of the invasion only fortified this idea. Boldly, she threw the window wide open.

‘Hey!’ she called. ‘What are you doing?’

The woman turned, too far away to see her face properly. She put up a hand to shield her eyes from the morning sun and squinted up at the window. ‘Hello,’ she said. ‘Sorry – I didn’t want to disturb you. It is rather early, I know.’

‘Does Harriet let you take her flowers?’

‘Of course. You didn’t think I was stealing them, did you?’

Not a ghost, Thea concluded, with a stab of disappointment. And apparently not a thief either. ‘Are they for the church?’ she asked, trying to inject some logic into the situation.

‘What? Oh no, of course not. Don’t be daft.’

‘Wait there,’ Thea ordered. ‘I’m coming down.’

She had not brought a dressing gown with her, but Harriet had thoughtfully provided one, which hung on the back of the door. It was pale blue and far too big, but she donned it anyway. Almost tripping on its trailing belt and the skittering spaniel, she got downstairs unscathed and flung open the front door. It was already warm, she noted, with satisfaction, all the clouds of the previous day quite dispelled.

‘So, who are you?’ she asked, trying to sound friendly.

‘Jemima Hobson. Daughter of Donny Davis. I gather he came to see you yesterday. Rather a cheek, if you ask me, but he seemed to think you didn’t mind.’

‘Oh! Pleased to meet you.’ She did not offer a hand to shake. There were roses and dressing gowns and a dog in the way. ‘No, I didn’t mind a bit. Do you live in Cranham?’

‘Actually, no. We’ve got a market garden place four or five miles away.’

‘But it’s so early,’ Thea groaned, brushing tangled hair out of her eyes.

‘Come on. It’s after eight. The sun’s been up since about five. I can’t bear to waste it this time of year. It all flies by so fast and you never know when we might be in for a month of rain.’ There was a restless, worried air to her, which echoed Donny’s remark about Jemima always being in a tizz.

‘True,’ said Thea, recognising her own thoughts of the past few days. She also remembered the people she had found herself amongst the previous June, and their similar habit of rising uncomfortably early. ‘I still think eight’s quite soon enough to get up.’

‘It may be for you – I have to fit so much in, I can’t lie around in bed. Dad sent me for the roses. Harriet won’t mind, I promise you.’

‘Is he up as well, then?’

‘Not yet, no. I generally go in about half past, to get his breakfast and help him get going. It’s not so bad this time of year, but in the winter he can take half an hour just to dress himself.’

‘Doesn’t he have somebody official – like a home help or something?’

Jemima Hobson gave her a look. ‘No, he doesn’t. He won’t consider it.’ She sighed impatiently, and then seemed to inwardly reproach herself. ‘You can see his point, I suppose. They’d send a different girl every time, who’d only want to get it all done as fast as possible and on to the next place. Even the cheerful ones are a pain in the backside. We had all that with my sister. I don’t think either of us could bear it all over again.’

‘He told me about your sister. I’m so sorry. It sounded awful.’

‘Yes, it was beastly. We miss her much more than we ever expected to, which probably sounds silly. I mean – you don’t think about it beforehand, do you? You can’t imagine what missing someone will be like.’

‘Right,’ said Thea, thinking about her dead husband and what a feeble phrase ‘missing him’ was when applied to the reality of the pain his loss caused. ‘I know exactly what you mean.’

‘Cecilia was seven years younger than me, and I adored her,’ said Jemima matter-of-factly. ‘From the first day she was born, I behaved as if she was mine. My mother had breast cancer in her early forties and was always tired and depressed, so I took the baby on. I hated going to school and leaving her. She was the centre of my life. And her bad heart just made it more important that I look after her properly.’

Thea had forgotten that she was standing outside in a voluminous blue dressing gown, talking to a woman she had never met before. She was hooked into the story of the Davis family, visualising how it must have been for them, wanting to know more. Here was the person who could answer some of the profound questions from the day before as well, if Thea could manage to phrase them tactfully.

‘It’s all so sad,’ she said, sincerely. ‘What happened to your mother?’

‘Nothing, really,’ Jemima grimaced. ‘She never quite got over the trauma and embarrassment and physical damage the cancer involved. She survived it physically, against the odds, and she’s still alive, but bit by bit she just got tireder and more depressed until it turned into senility, even though she’s not seventy-five yet. She just gave up when Cecilia died. She’s in a nursing home in Cirencester, more or less out of it. We don’t seem to have much time for her any more.’ She frowned. ‘That sounds bad, I suppose, but it’s the truth. Dad hardly even mentions her these days. She didn’t know me last time I visited. I’m not sure I can face going through that again, quite frankly.’

The story had lurched from sad to seriously lowering. Thea understood that Donny’s wife’s experience had been repeated in his younger daughter’s, in that they had both been subjected to extreme medical interventions designed to save their lives. The whole family must for years and years have been immersed in hospitals and medication and fear for the future. It happened to thousands of people, of course: the visits to the specialist a regular dramatic event in their lives, the repeated rounds of tests and X-rays and trials of the latest drugs. It became their sole topic of conversation, obsessively discussing symptoms in hushed voices. To their friends and neighbours they became ‘Sally with the bowel cancer’ or ‘Henry with the heart bypass’. Illness became a way of life, survival the sole goal, even if they did nothing more than sit in front of the telly all day.

She felt prompted to do something to lighten the mood before the whole day was spoilt.

‘There were just you two girls, then, were there?’

‘Oh, no. We’ve got a brother as well. He came between me and Cecilia. Silas, he’s called. He’s in Nigeria at the moment, doing something terribly noble with handicapped children.’

Thea grinned. She liked this busy restless woman. She liked the whole family, from what she’d learnt thus far – even the defeated mother and do-gooder brother. She liked their refusal to kowtow to the conventional norms of patienthood – especially where Donny was concerned. ‘Well, your father has a good spirit,’ she said unselfconsciously.

Jemima took a perfect yellow rose from the trug and sniffed it, her gaze on the Lodge two hundred yards away as if it was tugging at her. ‘That’s a nice way of putting it,’ she said thickly. ‘It takes a stranger to say something like that. To me he’s rather a nuisance most of the time.’

‘You’ve certainly got your hands full,’ Thea sympathised.

‘I’m not complaining. Families are prone to get complicated, after all. I’d rather have it like this than sit around all day with nothing to do. At least my own kids are behaving themselves, for the moment.’

‘You make me feel awfully lazy,’ Thea confessed. ‘But I did do something for your dad,’ she remembered. ‘I hope it wasn’t out of order, but I approached an alternative undertaker on his behalf. He said yesterday that he wanted to settle the details of his funeral, and did I know anybody, and as it happens—’ Belatedly she noticed the expression on Jemima Hobson’s face. ‘What? What’s the matter?’

‘Out of order isn’t even close,’ the woman snarled. ‘What in the world did you think you were doing? He doesn’t need to discuss his funeral, for God’s sake.’

‘Um …’ flailed Thea helplessly. ‘But he did say …’ Rapidly thinking back, she understood that she had been dreadfully precipitate. Donny had done little more than express a polite interest when Thea had told him about Drew. With shamefully little encouragement, she had gone flying to the phone moments after he’d left. Now it began to look as if she’d made a big mistake.

Jemima groaned aloud. ‘After all my efforts, you go and wreck everything on the first day you meet him. Didn’t it occur to you that things might not be as they seem on the surface? I can’t believe anybody could be so blunderingly insensitive as to do something like that. We all spend every waking moment trying to steer him away from anything morbid, for heaven’s sake.’

‘Wait a minute,’ Thea protested. ‘What’s so terrible about it? Drew’s utterly approachable and friendly. He’s not going to force anything onto Donny. We can cancel the whole thing if necessary.’ Besides, she wanted to add, there will have to be a funeral at some point.

‘Listen,’ Jemima said in a low hard voice. ‘We’re not happy with the way Dad’s been thinking. He’s started talking about assisted suicide and living wills. He’s scared stiff of ending up in hospital, dying slowly after weeks of being kept alive with tubes and machines and all that business. It’s getting to be an obsession with him. If you introduce some touchy-feely undertaker, who’ll tell him he can be reincarnated as a lovely cherry tree, he’ll just get worse. Don’t you see?’

Thea dug her heels in. ‘Not really. His attitude seems quite logical to me. But I admit I have been interfering where I shouldn’t. It never occurred to me it would cause trouble with his family.’

Jemima snorted. ‘You’ve been swayed by all the media hype and emotional appeals for changes to the law on suicide. It’s a million miles from the reality for actual individual people. If you ask me, it was better when suicide was illegal. People just had to put up with what fate dealt them in those days.’

‘I suppose you’re against divorce as well, for the same reasons?’

‘That’s a completely different issue, and you know it. I’m talking about all these idiots thinking they can have an easy painless death at the flick of a switch.’

‘I agree with you, more or less,’ Thea said, deflating much of the other woman’s animosity. ‘But I don’t agree that it helps to avoid the subject. Your father can cope with hearing your views, from what I’ve seen of him.’

‘He probably can. But I can’t. Have you ever talked to your own father about how and when he’ll die, and who’s going to help him?’

‘My father died last year. But no, we never had a conversation remotely like that.’

‘It’s as if an iron hand clutches your throat and stops the words coming out. You can think them, and practise saying them, but when it comes to the point, it just doesn’t happen. And I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s much better to keep everything superficial, take it a day at a time, and smell the flowers.’ She put the rose to her nose again to illustrate the point.

‘And that’s the general consensus in the family, is it?’

‘Not entirely. Edwina’s a bit of a problem. Dad got her to make some impossible promises, but I think he understands that she can’t hope to fulfil them.’

Until that moment Thea had forgotten the man in the woods – Philippe, the doctor who thought dying was easy. Had she stumbled into the midst of a whole community with passionate views about euthanasia? Was there some large factor in the argument that she had failed to grasp? Already she was losing sight of