4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Olympia Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

An abridged History of Capital Punishment, with additional bits about torture thrown in, potentially from another of Dr. George Ryley Scott's treatises. We're still sorting it out, but you can guess at the contents, and there are a few pictures, though no footnotes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

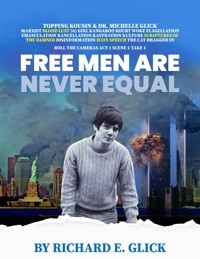

A History of Torture and Death

Anonymous

This page copyright © 2007 Olympia Press.

http://www.olympiapress.com

CHAPTER I. THE PRINCIPLES AND AIMS OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

CHAPTER II. MURDER AND ITS CAUSATION

CHAPTER III. THE CRAZE FOR JUDICIAL KILLING

CHAPTER IV. THE RISE AND DEVELOPMENT OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

CHAPTER V. CAPITAL PUNISHMENT TO-DAY

CHAPTER VI. THE WAR ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

CHAPTER VII. THE STATE'S RESPONSIBILITY FOR CRIME

CHAPTER VIII. THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE QUESTION OF INSANITY

CHAPTER IX. THE REPERCUSSIONS AND EFFECTS OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT ON SOCIETY AND THE INDIVIDUAL

CHAPTER X. AWAITING THE DAY OF DOOM

CHAPTER XI. THE EXECUTIONER

CHAPTER XII. CRUCIFIXION, PRESSING TO DEATH, DRAWING AND QUARTERING, BREAKING ON THE WHEEL, STRANGLING, “DEATH BY THE THOUSAND CUTS", SELF-EXECUTION BY HARA-KIRI, AND SHOOTING TO DEATH

CHAPTER XIII. DECAPITATION

Published by

Ben's Books Limited

102 Parkway London N.W.I Reprinted by

Colonna Press Ltd.

Queensway Hemel Hempstead

PART ONE. HISTORICAL AND SOCIOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

CHAPTER I. THE PRINCIPLES AND AIMS OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

I. The Concept of Vengeance IN all savage and primitive society the death penalty is purely retaliatory. Its origin lies in man's natural desire to return blow for blow, injury for injury, as expressed in the Biblical concept of an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. Blood-revenge is restricted in its conception. For practical purposes, this is an essential feature. There are numerous variations and modifications, but each extension or amplification is cumulatively dangerous. Thus, the consequences are potentially terrifying where every relative of the murdered person, whenever opportunity occurs, exacts vengeance on every relative of the murderer. In this manner arose those blood feuds which were pursued with such inhuman ferocity among certain savage tribes and in some so-called civilized countries. The concept of blood-revenge was a marked feature of Mosaic law. From a reading of the Second Book of Samuel, it is evident that, at one time, blood-revenge combined the utmost degree of savagery with an extremely embracive familial scope, but afterwards restrictive laws were introduced with the express object of preventing an itch for the gratification of personal revenge developing into an embracive family feud. According to the laws of Israel, where homicide was committed, the murdered person's nearest relative made himself the sole arbiter of guilt. Trial there was none. The law allowed such a relative to constitute himself judge, jury and executioner all rolled into one. So far as this god-given right to vengeance was concerned, it mattered little what particular type of homicide was involved. The fact of killing was enough to justify retaliation in kind. Thus, whether accidental or purposeful, the penalty was the same. There was, however, one way and one way only in which anyone guilty of accidental homicide might escape the consequences of this campaign of vengeance: he could seek the protection afforded by a “city of refuge”. Here and there, throughout the country, were to be found these “cities of refuge", and once within the purlieus of any one of them, proof of willful murder must be provided by the seeker of blood-revenge before he could justify his claim to exact vengeance. Thus: “But if any man hate his neighbour, and lie in wait for him, and smite him mortally that he die, and fleeth into one of these cities: then the elders of his city shall send and fetch him thence, and deliver him into the hand of the avenger of blood, that he may die. Thine eye shall not pity him, but thou shalt put away the guilt of innocent blood from Israel, that it may go well with thee.” The abolition of these “cities of refuge” and of all other, similar sanctuaries did not see the coincident abolition of the horrible custom of blood-revenge. It became essential, therefore, for tribes and families to take other measures for self-preservation, and these took the form of protective alliances. These compacts survived among primitive races throughout many centuries of the Christian era. Apropos of this, Dr. Thomson, in says: “These family treaties of alliance offensive and defensive, are intended to answer the same purpose that the ancient sanctuaries and 'cities of refuge' did; and they do it. When a man fleeing for life arrives among his allies, he is safe, so far as their utmost power to defend him can go; and they are to pass him on to more distant retreats if necessary. For this purpose, these compacts are extended all over the land.... Again: our friend says, in justification, that without these treaties of alliance they could not exist at all in this region of lawless Moslems, Metawelies, and Arabs. It is one of the cruel features of the that if the real murderer cannot be reached, the avengers of blood have a right to kill any other member of the family, then any relation, no matter how remote, and, finally, any member of this blood confederation. The weak would hence be entirely at the mercy of the strong, were it not for these alliances; and most of all—would the few Christians in Belad Besharah fall victims to the fierce non-Christian clans around them. This is their apology for such compacts, and it is difficult to convince them that this—as they believe—their only means of safety, is immoral. If you tell them that they should make the government their refuge, and appeal at once to the Pasha, they merely smile at your ignorance of the actual state of the country, and not without reason. Even in Lebanon, which the Allied Powers have undertaken to look after, I have known, not one, but many horrible tragedies. Several of my intimate acquaintances have literally been cut to pieces by the infuriated avengers of blood, and in some instances, these poor victims had no possible implication with the original murder, and only a remote connection with the clan involved in it. Were it not for these confederations, there would be no safety in such emergencies, and they do actually furnish an important check to the murderous designs of 'avengers'. I once inquired of a friend if he were not afraid to go into a certain neighbourhood where a murder had been committed by one of his confederation. 'Oh no', he replied, 'our aileh (confederation) can number twelve hundred guns, and our enemies dare not touch me; and, besides, the matter is to be made up by our paying a ransom.' This is the ordinary mode of settling such questions.” II. IT is natural that this somewhat primitive concept of the punishment of murder and injury by a species of personal or private revenge on the part of the relatives, should devolve into an act of retribution instituted on behalf of these relatives by the governing power. In these circumstances, says Sumner, “injuries became crimes and revenge became punishment.” In its early stages, at any rate, any action by the State was purely retaliatory: it embraced no idea other than that of vengeance. As the people begin to realize the possibilities of the exercise by the State, or in other words, by themselves as an executive body, of tins privilege of retaliatory punishment in contradistinction to the narrower one of personal blood-revenge, there opens up the prospect of preventive action in a much wider sense than is possible with any individualistically-motivated idea of vengeance. Thus they extend and develop a system of State punishment, or in other words a penal system. The people realize that in assuming the responsibility for exacting revenge by punishing any individual guilty of an offence against another member of society, they are providing self-protection against potential injury. In this way, they carry a system of revenge to its ultimate triumph: that is, consciously or unconsciously, they turn it into a system of deterrence. Despite the formation of penal codes, it must be kept well in mind that early law-makers still looked upon the crime of murder (or, indeed, any other crime involving serious injury) as being one for which revenge was due to the sufferer or his relatives. The idea as such, and divorced from personal revenge, did not enter into the matter. It was still a case of revenge or retaliation demanded by the injured party, whose right to this revenge was recognized by the State. The real difference between this retributive action by the State and the old system of blood-revenge, lay in the fact that no longer was the nearest kinsman allowed to fulfil the triple role of judge, jury and executioner, or indeed any role at all beyond that of formulating his for revenge. The State took over these powers and specified what form of revenge should be exacted or what type of restitution should be made. It is important to remember that in the early days of civilization there were no prisons. Detention as a form of punishment or deterrence was unthought of. The doctrines of and restitution were universally upheld and applied. A system of fines was instituted. These fines varied according to the nature of the injury to be placated. Often a fine, payable to the murdered person's relatives, was a possible alternative to the punishment of death. The Anglo-Saxons and Danes, according to Baring Gould, had an elaborate system of fines. Says this authority: “Capital punishments were sanctioned, but in all cases an opportunity was offered for the substitution of a fine. Thus, by the law of King Ina, if a thief were caught, he was sentenced to death, but his life could be redeemed by pecuniary satisfaction being made to the persons robbed. So (lie fine inflicted on a murderer was regulated according to the sum at which the life of the murdered party was valued; thus, if a man slew a freeman, he had to make compensation to the amount of 100 shillings, but for the murder of a thrall a much less sum was demanded. If a freeman slew his thrall, he paid a nominal fine to the king for a breach of the peace; but if a slave killed his master, the doctrine of blood for blood was carried into effect, as the thrall had no personal property to pay in compensation for his crime.” It was not until the time of Henry the Second that English law began to uphold the doctrine of crime being more than a personal affair between the guilty party on the one hand and the injured party on the other, but as something to be recognized as a wrong committed against the nation. This realization was not without dangerous implications. For it opened up possibilities for persecution and tyranny on a mammoth scale. Once the State's right to exact vengeance on behalf of its citizens was accepted and approved, the way for the exercise of such tyranny and persecution was clear. This is evidenced by the manner in which subscribers to rival religions, on the ground of being guilty of heresy, were subjected to continuous and unremitting persecution. To this end, crimes were manufactured irrespective of the possibility of their commission. We have an illustration of this in the wholesale persecution of the witches in the seventeenth century. How warped the mind of a learned judge of the day could be, is evidenced in the directions to the jury, given by Sir Matthew Hale, in connection with the trial of Rose Cullender and others at Bury St. Edmunds on March 10th, 1662. The famous jurist told the jury “they had two things to enquire after. First, whether or no these children were bewitched. Secondly, whether the prisoners at the bar were guilty of it That there were such creatures as witches", continued Sir Matthew, “he made no doubt at all; for, first, the Scriptures had affirmed so much. Secondly, the wisdom of all nations had provided laws against such persons, which is an argument of their confidence of such a crime. And such hath been the judgment of this kingdom, as appears by that Act of Parliament which hath provided punishment proportionable to the quality of the offence; and desired them strictly to observe their evidence; and desired the great God of heaven to direct their hearts in this weighty thing they had in hand; for to condemn the innocent, and to let the guilty go free, were both an abomination to the Lord.” The belief in the mythical and apocryphal crime of witchcraft was bad enough in itself; the means that were adopted to prove the practice of the crime by those charged with it, were even worse. Witch-finders, as they were called, were prevalent in every European country, including Britain, and their methods, upheld and justified by the judges and theologians of the day, were of a character to make what passed for justice stink to high heaven. The following account, culled from the commentary, attributed to Voltaire, appended to the 1799 edition of Beccaria's Essay, is sufficiently revealing. “In the year 1748, in the bishopric of Wurtsburg, an old woman was convicted of witchcraft and burnt. This was an extraordinary phenomenon in the present century. But how incredible it seems, that a people, who boasted of their reformation, and of having trampled superstition under their feet, and who flattered themselves that they had brought their reason to perfection; is it not wonderful, I say, that such a people should have believed in witchcraft; should have burnt old women accused of this crime, and that above a hundred years after the pretended reformation of their reason? In the year 1652, a country woman, named Michelle Chaudron, of the little territory of Geneva, met the Devil on her way from the city. The Devil gave her a kiss, received her homage, and imprinted on her upper lip, and on her right breast, the mark which he is wont to bestow upon his favourites. This seal of the Devil is a little sign upon the skin, which renders it insensible, as we are assured by all the demonographical civilians of those times. The Devil ordered Michelle Chaudron to bewitch two young girls. She obeyed her master punctually. The parents of the two girls accused her of dealing with the Devil. The girls being confronted with the criminal, declared, that they felt a continual prickling in some parts of their bodies, and that they were possessed. Physicians were called, at least men that passed for physicians in those days. They visited the girls. They sought for the seal of the Devil on the body of Michelle, which seal is called, in the verbal process, the Into one of these marks they plunged a long needle, which was already no small torture. Blood issued from the wound, and Michelle, testified by her cries that the part was not insensible. The judges, not finding sufficient proof that Michelle Chaudron was a witch, ordered her to be tortured, which infallibly produced the proof they wanted. The poor wretch, overcome by torment, confessed, at last, every thing they desired. The physicians sought again for the Satanical mark, and found it in a little black spot on one of her thighs. Into this, they plunged their needle. The poor creature, exhausted and almost expiring with the pain of the torture, was insensible to the needle, and did not cry out She was instantly condemned to be burnt; but the world beginning at this time to be a little more civilized, she was previously strangled. At this period, every tribunal in Europe resounded with such judgments, and fire and faggot were universally employed against witchcraft as well as heresy.” III. WITH the transference of homicide from its ancient status as a mere personal affair between two parties, or the respective relatives of these two parties, into a question of the State dealing out justice, the whole aspect of criminal law changed. What had been no more than the regulation and limitation of private quarrels, became a system of State-dispensed justice that eliminated altogether the feud element Moreover, the people as a whole became concerned in what had hitherto been looked upon as personal quarrels between individuals, and quickly the position developed until the interests of those immediately affected by the crimes became of little importance compared with the concern of society as a body in criminal prophylaxis. The State, having adopted the role of avenger, evolved a scheme of dispensing justice, according to its lights, in which the views and interests of the three parties concerned—criminal, victim, and the State;—played their parts in inverse order, the State occupying a role of outstanding importance. In this way, there was evolved a penal system featuring three clearly defined aims, to wit: (a) the prevention of a repetition of the offence by the murderer, and its imitation by another person or persons; (b) the provision of a punishment befitting the crime, in accordance with the ancient theory of and (c) the indemnification of the deity, of society, and of the relatives of the murdered person by a specifically devised form of atonement. These various objectives were, it was contended, achievable in one way and one way only, by the judgment of death. As deterrence ranked higher and higher in importance, the State extended the range of capital punishment by adding crime after crime to the list of offences for which it was deemed to be a fitting penalty. The original demand of an eye for an eye developed into a claim for the culprit's life to satisfy the theft of a shilling or the cutting down of a tree. Torture before, and degradation after, were added to the punishment of death. No means was deemed too foul, too savage, or too inhuman, if it were thought to prove an effective deterrent. Not until well towards the close of-die eighteenth century was it realized that this doctrine was unjustifiable. Blackstone, the great English jurist, writing on this very point, said: “For though the end of punishment is to deter men from offending, it never can follow from thence that it is lawful to deter them at any rate and by any means; since there may be unlawful methods of enforcing obedience even to the justest laws.” Penological reform started with the repeal of torture as an additional punishment; and continued with the repeal of capital punishment for petty crimes, eventually leaving murder as the most outstanding of the few crimes involving the death penalty. Murder, it is contended, ranks as crime for which society must demand the judgment of death; this demand, it is held, is in accord with justice; with necessity, as envisaged in the safety of the public; and with the policy of atonement. Recent trends, generally speaking, are in the direction of a realization that punishment is justifiable only on the grounds of deterrence. Charles Bradlaugh's contention that “punishment which is mere revenge is itself a crime” is incontrovertible. All the same, these concepts are mainly idealistic. Retaliation still ranks high in the average man's notion of justice; the revenge motif is still embodied in penal law, and-therefore cannot be dismissed as wholly unimportant, or considered to be a completely negligible factor in present-day criminology. In any modernistic consideration of crime, as a result of concentration on the problem of the murderer, the case for the victim's relatives is in danger of playing a minor role or of being overlooked altogether. In twentieth-century penology the question of deterrence on the one hand and of reformation on the other are apt to override and eclipse all other considerations. In particular the original aim of capital punishment is totally lost sight of. Any examination, along historical principles, of this original aim and of the State's mandate gives rise to the question of how far has modern society departed from this basic mandate in neglecting to carry out the principle of Or to put it another way, how far are the relatives of the murderer's victim justified in considering they have a right to demand, as their just due, vengeance in the form of a life for a life? It must ever be remembered that whatever arguments may be advanced by humanitarians and those versed in penological science, with regard to the objects of punishment, vengeance is all important, ousting and drowning in its clamorous insistence every other objective; and, because of this, with some justification, the claim is urgable that in the making of this concession and that, particularly in relation to the question of responsibility, the sex and the age of the criminal, and other factors (that to the injured parties have little or no weight), all of which involve, either partially or wholly, a rescinding of the vengeance motif, the State is guilty of failing to carry out its obligations to the victim's relatives. On the other hand, arising out of this argument is the question of how far is the State justified in asking or compelling a body of officials to act, in the most cold-blooded way possible, as dispensers of a form of vengeance that is out of tune with civilization as now constituted but is called for by these relatives of the victim and such other members of society as support the principle of Although the original right and privilege (now lost sight of) granted to the murdered person's nearest relative to act as judge, jury, and executioner, cannot be tolerated in the modern State, there would appear to be something in the contention, conceivably presentable, that, in a State which upholds capital punishment, the office of executioner should be the privilege, or rank as the duty, of the relative who is insistent in demanding that such a form of retribution be carried out. In consequence of the elimination of vengeance (as an ideological concept at any rate) from punishment, these points of view have received little or no attention, but in considering the problems concerned in the reform of the existing system of capital punishment they merit careful examination, especially in relation to the system of granting reprieves. In any event, the claims of the victim's relatives would appear to underline the need for the fullest publicity being given to the why reprieves are granted. It may well be, however, that adequate consideration of these very points might do much towards bringing about a changed outlook on the part of these injured relatives. The question of what would you feel like if your wife, or husband, or sister, happened to be the murderer's victim?—a question so triumphantly propounded by the upholder of capital punishment to the abolitionist—is a tacit admission of the validity of a cry for vengeance which, in these days (and this is the crux of the matter), is, and can be, rarely satisfied. In any modern State where, with the full approval of society (apparently even of those who are insistent in the demand for capital punishment being retained and the old principle of being applied), only murderers of specific and selected types are punished or punishable, and where homicide in many of its commonest forms is not even a criminal offence, the illogicality of any argument in favour of the death penalty based on the vengeance motif must be apparent to the individual of mature intelligence. When this illogicality is and realized, and when it is also realized that the certainty of punishment in the form of a protracted indeterminate term of imprisonment is far more desirable than the risk of the murderer going free, the whole multifaceted problem will appear in a different light. As matters now stand, for the very reasons already given, the injured relatives are, sometimes completely and more often partially, dissatisfied with the treatment which the murderer receives at the hands of the State. Mixed up with all tins is the fearful responsibility of the State for the crimes it elects to punish (see Chapter VII), a responsibility it cannot evade by a mere matter of terminology. There is a possibility that some day it will be realized how futile is the effort to abolish a crime by a method, of which the outstanding feature, despite every attempt at justification and every form of apologia, is that its basic character is precisely the same as the crime itself. Little more than a century ago, the pickpockets, while a thousand of their fellow-citizens gazed at the spectacle of a thief swinging on the gallows, took the opportunity to ply their craft; to-day, while the government, to the accompaniment of the hurrahs of its supporters, kills off this type of murderer and that, a dozen other types emulate the act of the State, and under one name and another, kill with comparative impunity. “What is truth?” said Pontius Pilate, and would not wait for an answer. And had Pontius Pilate lived to-day, well might he have asked, “What is murder?”

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!