Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

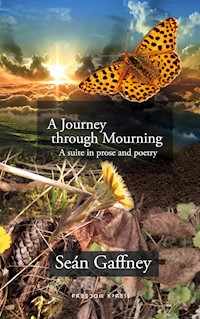

In Seán Gaffney's fifth suite of poems he is presenting a mixture of prose and poetry in a strong and touching celebration of his son, Dara Gaffney, who at the age of fourteen was diagnosed with leukemia. Only a few months later Dara died from his disease. What is taking place here is an essential part of Seán's life, where he holds Dara within himself during the mourning process that simultaneously is a life process, in a recurring dialogue each year at Dara's birth and death days. A life journey with mourning as both a driving force and an emotional landscape.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 96

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

PART I 1986 – 2008

A Journey through Mourning

PART II 2008 – 2011

Still on my way

PART III 2011 – 2021

Your Presence

Introduction

As I have grown older my health issues have also grown both in quantity and potential seriousness – in a word, my mortality. One of the many consequences of this insight was that a year would come when I would no longer be alive to write a poem in celebration of my dead son’s birth nor in acknowledgement of his death. Both would come and go unremarked.

So I decided to gather together what was available to me of what I had written over the years with Dara in mind and publish it in a book. This book.

Some of my writing has disappeared due to my technological ignorance and/or incompetence, in moving from PC to MAC and laptop to desktop and from one apartment to another a number of times in terms of hard copies.

So what you read here is what I had available to publish up to and including 2021.

Warmly,

Seán Gaffney

Stockholm, August 2021

PART I

1986 - 2008

A Journey through Mourning

In memory of my son, Dara Gaffney

May 9, 1972 – August 9, 1986

(Originally published 2008 - see references)

Allow me to begin with some extracts from the interview by Belinda Harris, published in the British Gestalt Journal (Gaffney, 2008), which started me off on the reflections described in this article:

Belinda: I’ll start with a personal question, Seán. What brought you to Gestalt therapy? Why gestalt for you, at whatever point in your life it was?

Seán: There are probably two answers, or one answer embedded in the other. Mm. In fact, I first clearly understood and publicly acknowledged their connection only a few days ago, at Charlie Bowman’s pre-conference workshop on the history of Gestalt therapy, which included our own histories as practitioners. So my answer begins in my earlier life, when before my 18th birthday I entered a Cistercian monastery and felt completely at home. I really, really felt it. But before my two year novice period was up my novice master, Father Ambrose, called me and said ‘I’ve been thinking a lot about you, brother, and you don’t belong here. You’re a teacher, a communicator. If you really want to be a priest be a preacher but the contemplative life is just a waste of your talents.’

I have described this experience in the first issue of Inner Sense (Gaffney 2007). It has become more and more formative for me as I look back on my life, and now more clearly connected to the topic of this article: a journey through mourning and the meaning of a life…

Seán: Anyway, to get back to answering your question about what brought me to Gestalt therapy: the second and more formal, rational answer would be: In 1986 my youngest son died of leukaemia. He went very, very quickly, exactly two months and one week from diagnosis to death…

And later in the interview:

My dead son is involved here somewhere in another, more directly influential way. One of the things I did as a consequence of that period around his death and his mother’s obvious painful grieving was to decide’ ‘I’m going to become a better person. I probably wasn’t the best father in the world; I probably favoured his big brother more. I clearly wasn’t a good support to my wife. I’ve got to be a better person. I need to do something to be a better person’. When I graduated from the Gestalt Academy of Scandinavia and the group of us were sitting there I said, ‘Thanks to my son, I promised myself to be a better person, and thanks to these four or five years I believe I’m becoming one”

So let me now, after a brief detour into the safer territory of quoted references, go straight to the point: shortly after the fourteenth birthday of my youngest of two sons, he became ill, with very diffuse symptoms. I took him to our local clinic, where the diagnosis was an infection of some sort, with prescribed antibiotics and a week’s rest. He appreciated the week off school, though did not seem to be getting over his symptoms of tiredness, mild though diffuse pain, and a general listlessness. Despite his prescribed freedom with no school and no homework, he showed little interest in TV or videos.

On June 1, 1986, he had severe pain, mainly in his stomach. His mother – a social worker student and a part-time assistant nurse – took him to the emergency ward at our local hospital, where she herself worked. I was away, teaching. My wife phoned me that evening to say that Dara had been immediately transferred to the cancer ward of the Children’s Hospital, which, she knew, was the leukaemia ward.

I returned immediately and went to visit him. He was clearly unwell and in pain. My wife was very concerned, using her experience in the hospital and conversations with the nursing staff . I was…well, optimistic is the wrong word. Maybe re-assured that he was in a good hospital and with my belief that treatment worked.

Two days later, my wife and I had a meeting with his doctor, a soft-spoken and gentle man originally from northern Africa. He declared the diagnosis – acute myelocetic leukaemia – and spoke of the chemotherapy treatment that would start immediately and continue for about two or up to three months. If the cancer was arrested then, it would be time to maybe start looking at such interventions as a bone marrow transplant and he would need to start taking samples to establish who would be a suitable donor, probably our oldest son. He was clear about the statistics: 60% chance of improvement, 40% chance of moving into a terminal condition. For this particular form of leukaemia, the average for Sweden (population 8.5 million) was four cases per year.

My son was in the leukaemia ward on the eighth floor of the children’s hospital. The ninth floor had been adapted for parents and relatives to spend nights there in order to be near their children. My wife and I took a room there so that one of us at least would always be around, day and night, using a shift system on weekdays, and staying there for most of the weekend. My wife and I re-arranged our work schedules so that we could attend to both our sons.

Reflecting back to this period, I am now more aware than I was then of the differences in how my wife and I heard and interpreted the information we regularly received. For her, the doctor was preparing us for the worst. For me, he was keeping us informed of progress without making any promises. She became more and more withdrawn, at times impossible to reach in any way that I knew how. We became more distanced from each other, sometimes only meeting briefly as we took over from each other at the hospital. The few hours we might be at home with our other son, we did the practical things together that had to be done and otherwise kept our exchanges to a social minimum.

As we moved through July, it was becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish between the impact of his leukaemia and the impact of the chemotherapy on Dara’s condition. His immune system was degraded by the treatment and he was susceptible to heavy colds, sudden fevers, exhaustion, complete loss of appetite, and days which he slept through from one to the next.

By the end of July, a mere two months after admission to the hospital, his condition was worsening on a daily basis. All talk of a bone marrow transplant was now out of the question. The personnel moved an extra bed into Dara’s room so that my wife and I could choose to sleep there with him in his room. I slept there the three last nights of his short life. My wife was working nights during this time, dropped in to see him during the night, and slept at home during the daytime.

When I awoke on the morning August 9, 1986, Dara was asleep, breathing shallowly and his whole body burning hot with fever. There was an intern on duty that morning and I asked him to check on my son and tell me what was happening. He asked me where my wife was. I told him that she was at home, sleeping.

“I think you better call her, and get her here” he said. I did, and she came. We were at our son’s bedside when he died, early that afternoon.

Our eldest boy, Naoise, was on his way back from Ireland that same day. Because of very strained relations between my wife and my family in Dublin, none of us had been back to Ireland since coming to Sweden, 11 years earlier. Naoise was a dedicated scout and troop leader, and, the previous year, his troop had planned a study visit to Ireland in the first week of August, ending this very day. I had earlier phoned a close friend of mine and told him of the situation. With an amazing effort and great ingenuity, he had traced Naoise to the harbour where he was waiting to board the ferry. With the help of the ferry personnel and scout leaders, Naoise was put in a taxi and was on his way to Dublin Airport with a flight booked by my friend back to Stockholm where he would be met and brought straight to the hospital.

His brother died while all this was happening. The ward staff arranged for Dara’s body to be brought to the hospital chapel so that Naoise could say his farewell when he arrived later that evening.

(Months later, Naoise told me that he had spoken with Dara about the trip to Ireland and his own willingness to stay in Sweden. I was amazed and moved to hear that Dara had spoken of possibly dying, and that he did not want to deprive his brother of a trip that was so important to him. If he went, and Dara died, then Naoise would anyway have been back to Ireland and met their cousins, whom Dara did not remember – he was two years old when we moved to Sweden. If he didn’t go, and Dara died, then this would always be between them…)

As is common in Sweden and a shock to me, the funeral was to be some 10 days later. My wife reminded me of a christening we had attended at the Catholic church in central Stockholm, where we had both been impressed by the priest, a German Jesuit whose name I got from the father of the christened child. I phoned the church and found myself speaking with Pater Peter Hornung for almost an hour. I could feel and sense his care, gentleness and warmth.