9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

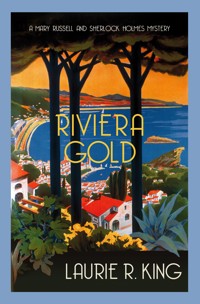

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Mary Russell & Sherlock Holmes

- Sprache: Englisch

1923. Mary Russell Holmes and her husband, the retired Sherlock Holmes, are enjoying summer on their Sussex estate when they are visited by Miss Dorothy Ruskin, an archeologist just returned from Palestine. She leaves in their protection an ancient manuscript which hints that Mary Magdalene was an apostle--an artifact certain to stir up a storm in the Christian establishment. When Ruskin is suddenly killed in a tragic accident, Russell and Holmes find themselves on the trail of a fiendishly clever murderer.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 434

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR LAURIE R. KING

‘The Mary Russell series is the most sustained feat of imagination in mystery fiction today, and this is the best instalment yet’ Lee Child

‘This series are bestselling books because Laurie R. King captures the voice and character of Holmes as well as any of the thousand and more pastiches that have been written in imitation of Conan Doyle. But this is more than a mere copy. The narrative … is completely absorbing and motivates the reader to want to read the rest of the series’ Historical Novels Review

‘Excellent … King never forgets the true spirit of Conan Doyle’ Chicago Tribune

‘Outstanding examples of the Sherlock Holmes pastiche … the depiction of Holmes and the addition of his partner, Mary, is superbly done’ Mystery Women

‘All [Laurie R King books] without exception, leave me with a feeling of immense satisfaction at the quality of the story and the writing’ It’s a Crime Blog

A LETTER OF MARY

LAURIE R. KING

For my brother Leahcim Drawde Nosdrahcir and his family From his sister Eiraul EEL

EDITOR’S PREFACE

THIS IS THE THIRD in a series of manuscripts taken from a trunk full of odds and ends that was sent to me a few years ago. The puzzle of its origin and why I was its recipient is far from solved. In fact, it becomes more mysterious with each manuscript I publish.

After the first of Mary Russell’s stories (The Beekeeper’s Apprentice) came out, I received a cryptic postcard that said merely: ‘More to follow.’ After the second (A Monstrous Regiment of Women), the following newspaper clipping arrived in the mail:

OXFORD PUNT FOUND IN LONDON

A group of Japanese businessmen on a river cruise yesterday caught and towed to Hampton Court a punt which police have determined originated at Folly Bridge in Oxford. In it were found clothing and a pair of glasses. The Thames Authority has no suggestion as yet how a punt could manoeuvre the locks and deeper stretches of river.

I rose to the challenge. A bit of research determined that the clipping was a filler in the London Times, dated three weeks before the book’s publication date. The subsequent phone calls to England cost me an arm and a leg, but eventually I discovered that the clothing (trousers, sensible shoes, and a blouse) was that of a tall, thin woman, and it had been found carefully folded on the cushions, with the glasses on top. There was no suicide note. The pole was in the boat (a punt is not rowed or motorised, I gather, but shoved along with a wooden pole). Downstream from Oxford, the river becomes too deep for the punter to reach the bottom.

I even found out that the police dusted the thing for prints, which sounded like a joke until my informant told me how much a wooden punt costs nowadays. With a vague idea that this might someday help me find where my trunk had come from, I asked for a set of the prints. It took a while to clear this with the higher authorities, but I did after some months receive a copy of the forensic report, which informed me that they had been made by two people, both with long, thin hands, one of them slightly bigger and thus probably male, the other with a scar across one of the pads. The scarred ones had been found on the glasses.

Interestingly enough, the fingerprints taken from the sides of the punt match those on a filthy clay pipe that was in the trunk with the manuscripts.

I should also mention that the inlaid box described in the following pages does exist, although when it reached me, there was no manuscript inside. It did hold a pair of black-lensed glasses, a dainty handkerchief embroidered with the letter M, and a key.

The key, I have been told, is to a safety-deposit box. There is absolutely no way of knowing where that box is.

– Laurie R. King

… I would terrify you by letters.

– THE SECOND LETTER OF PAUL TO THE CORINTHIANS 10:9

Contents

PART ONE

TUESDAY, 14 AUGUST 1923 – FRIDAY, 24 AUGUST 1923

A pen is certainly an excellent instrument to fix a man’s attention and to inflame his ambition.

– JOHN ADAMS

CHAPTER ONE

α

alpha

THE ENVELOPE SLAPPED DOWN onto the desk ten inches from my much-abused eyes, instantly obscuring the black lines of Hebrew letters that had begun to quiver an hour before. With the shock of the sudden change, my vision stuttered, attempted a valiant rally, then slid into complete rebellion and would not focus at all.

I leant back in my chair with an ill-stifled groan, peeled my wire-rimmed spectacles from my ears and dropped them onto the stack of notes, and sat for a long minute with the heels of both hands pressed into my eye sockets. The person who had so unceremoniously delivered this grubby interruption moved off across the room, where I heard him sort a series of envelopes chuk-chuk-chuk into the wastepaper basket, then stepped into the front hallway to drop a heavy envelope onto the table there (Mrs Hudson’s monthly letter from her son in Australia, I noted, two days early) before coming back to take up a position beside my desk, one shoulder dug into the bookshelf, eyes gazing, no doubt, out the window at the Downs rolling down to the Channel. I replaced the heels of my hands with the backs of my fingers, cool against the hectic flesh, and addressed my husband.

‘Do you know, Holmes, I had a great-uncle in Chicago whose promising medical career was cut short when he began to go blind over his books. It must be extremely frustrating to have one’s future betrayed by a tiny web of optical muscles. Though he did go on to make a fortune selling eggs and trousers to the gold miners,’ I added. ‘Whom is it from?’

‘Shall I read it to you, Russell, so as to save your optic muscles for the metheg and your beloved furtive patach?’ His solicitous words were spoilt by the sardonic, almost querulous edge to his voice. ‘Alas, I have become a mere secretary to my wife’s ambitions. Kindly do not snort, Russell. It is an unbecoming sound. Let me see.’ I felt his arm come across my desk, and I heard the letter whisper as it was plucked up. ‘The envelope is from the Hôtel Imperial in Paris, a name which contains distinct overtones of sagging mattresses and ominous nocturnal rustling noises in the wardrobe. It is addressed simply to Mary Russell, no title whatsoever. The hand is worthy of some attention. A woman’s writing, surely, though almost masculine in the way the fingers grasp the pen. The writer is obviously highly educated, a “professional woman”, to use the somewhat misleading modern phrase; I venture to say that this particular lady does not depend on her womanliness for a livelihood. Her t’s reveal her to be an impatient person, and there is passion in the sweeps of her uprights, yet her s’s and a’s speak of precision and the lower edge of each line is as exact as it is authoritative. She also either has great faith in the French and English postal systems or else is so self-assured as to consider the insurance of placing her name or room number on the envelope unnecessary. I leant towards the latter theory.’

As this analysis progressed, I recovered my glasses, the better to study my companion where he stood in the bright window, bent over the envelope like a jeweller with some rare uncut stone, and I was hit by one of those odd moments of analytical apartness, when one looks with a stranger’s eyes on something infinitely familiar. Physically, Sherlock Holmes had changed little since we had first met on these same Sussex Downs a bit more than eight years before. His hair was slightly thinner, certainly greyer, and his grey eyes had become even more deeply hooded, so that the resemblance to some far-seeing, sharp-beaked raptor was more marked than ever. No, his body had only exaggerated itself; the greatest changes were internal. The fierce passions that had driven him in his early years, years before I was even born, had subsided, and the agonies of frustration he had felt when without a challenge, frustration that had led him to needles filled with cocaine and morphia, were now in abeyance. Or so I had thought.

I watched him as his long fingers caressed the much-travelled envelope and his eyes drew significance from every smudge, every characteristic of paper and ink and stamp, and it occurred to me suddenly that Sherlock Holmes was bored.

The thought was not a happy one. No person, certainly no woman, likes to think that her marriage has lessened the happiness of her partner. I thrust the troublesome idea from me, reached up to rub a twinge from my right shoulder, and spoke with a shade more irritation than was called for.

‘My dear Holmes, this verges on deductio ad absurdum. Were you to open the envelope and identify the writer, it just might simplify matters.’

‘All in good time, Russell. I further note a partial set of grimy fingerprints along the back of the envelope, with a matching thumb print on the front. However, I believe we can discount them, as they have the familiar look of the hands of our very own postal-delivery boy, whose bicycle chain is in constant need of repair.’

‘Holmes, my furtive patachs await me. The letter?’

‘Patience is a necessary attribute of the detective’s make-up, Russell. And, I should have thought, the scholar’s. However, as you say.’ He turned away, and the sharp zip of a knife through cheap paper was followed by a dull thud as the knife was reintroduced into the frayed wood of the mantelpiece. There was a thin rustle. His voice sounded amused as he began to read. ‘“Dear Miss Russell”, it begins, dated four days ago.

Dear Miss Russell,

I trust you will not be offended by my form of address. I am aware that you have married, but I cannot bring myself to assign a woman her husband’s name unless I have been told that such is her desire. If you are offended, please forgive my unintentional faux pas.

You will perhaps remember me, Dorothy Ruskin, from your visit to Palestine several years ago. I have remained in that land since then, assisting at three preliminary digs until such time as I can arrange funding for my own excavations. I have been called back home for an interview by my potential sponsors, as well as to see my mother, who seems to be on her deathbed. There is a matter of some interest which I wish to lay before you while I am in England, and I would appreciate it if you would allow me to come and disturb your peace for a few hours. It would have to be on the 22nd or 23rd, as I return to Palestine directly when my business is completed. Please confirm the day and time by telegram at the address below.

I believe the matter to be of some interest and potentially considerable importance to your chosen field of study, or I would not be bothering you and your husband.

I remain, Most affectionately yours, Dorothy Ruskin

‘The address below is that of the Hôtel Imperial,’ Holmes added.

I took the letter from Holmes and quickly skimmed the singular hand that strode across the flimsy hotel paper. ‘A decent pen, though,’ I noted absently. ‘Shall we see her?’

‘We? My dear Russell, I am the husband of an emancipated woman who, although she may not yet vote in an election, is at least allowed to see her own friends without male chaperonage.’

‘Don’t be an ass, Holmes. She obviously wants to see both of us, or she would not have written that last sentence. We’ll have her for tea, then. Wednesday or Thursday?’

‘Wednesday is Mrs Hudson’s half day. Miss Ruskin might have a better tea if she came Thursday.’

‘Thank you, Holmes,’ I said with asperity. I admit that cooking is not my strong point, but I object to having my nose rubbed in the fact. ‘I’ll write to let her know either day is fine but that Thursday is slightly better. I wonder what she wants.’

‘Funding for an all-woman archaeological dig, I shouldn’t wonder. That would be popular with the British authorities and the Zionists, would it not? And think of the attraction it would have for the pilgrims and the tourists. It’s a wonder the Americans haven’t thought of it.’

‘Holmes, enough! Begone! I have work to do.’

‘Come for a walk.’

‘Not just now. Perhaps this evening I could take an hour off.’

‘By this evening, you will be bogged down to the axles in the prophet Isaiah’s mud and too irritable to make a decent walking companion. You’ve been rubbing your bad shoulder for the last forty minutes although it is a warm afternoon, which means you need to get out and breathe some fresh air. Come.’

He held out one long hand to me. I looked down at the cramped lines marching across the page, capped my pen, and allowed him to pull me to my feet.

We walked along the cliffs rather than descending the precipitous beach path, and listened to the gulls cry and the waves surge on the shingle below. The good salt air filled my lungs, cleared my head, and took the ache from my collarbone, and eventually my thoughts turned, not to the intricacies of Hebrew grammar but to the implications of the letter that lay on my desk.

‘What do you know of the archaeology of Palestine, Holmes?’

‘Other than what we discovered when we were there four and a half years ago – which trip, as I recall, was dominated by an extraordinary number of damp and hazardous underground chambers – almost nothing. I suspect that I shall know a great deal more before too much longer.’

‘You think there is something to Miss Ruskin’s letter, then?’

‘My dear Russell, I have not been a consulting detective for more than forty years for nothing. I can spot a case sniffing around my door even before it knows itself to be one. Despite what I said about allowing you to see her alone, your Miss Ruskin – yes, I know she is not yours, but she thinks she is – your Miss Ruskin wishes to present a puzzle to the partnership of Holmes and Russell, not merely to Mary Russell, a brilliant young star on the horizon of academic theology. Unless you think my standard degree of megalomania is becoming compounded by senility,’ he added politely.

‘Megalomania, perhaps; senility, never.’ I stood and watched a small fishing boat lying off shore, and I wondered what to do. The work was going slowly, and I could ill afford to take even half a day away from it. On the other hand, it would be a joy to spend some time with that peculiar old lady, whom I indeed remembered very well. Also, Holmes seemed interested. It would at least provide a distraction until I could decide what needed doing for him. ‘All right, we’ll have her here a day sooner, then, on the Wednesday. I’ll suggest the noon train. I’m certain Mrs Hudson can be persuaded to leave something for our tea, so we need not risk our visitor’s health. I also think I’ll go to town tomorrow and drop by the British Museum for a while. Will you come?’

‘Only if we can stay for the evening. They’re playing Tchaikovsky’s D at Covent Garden.’

‘And dinner at Simpson’s?’ I said lightly, ruthlessly ignoring the internal wail at the waste of time.

‘But of course.’

‘Will you go to the BM with me?’

‘Briefly, perhaps. I had a note from the owner of a rather bijou little gallery up the street, inviting me to view the canvas of that Spaniard, Picasso, that I retrieved for them last month. I should be interested to see it in its natural habitat, as it were, to determine if it makes any more sense there than it did in that warehouse on the docks where I found it. Although, frankly, I have my doubts.’

‘That’s fine, then,’ I said politely. Suddenly, Holmes was not at my side but blocking my way, his hands on my shoulders and his face inches from mine.

‘Admit it, Russell. You’ve been bored.’

His words so echoed my own analysis of his mental state that I could only gape at him.

‘You’ve been tucked into your books for a solid year now, ever since we came back from France. You might be able to convince yourself that you’re nothing but a scholar, Russell, but you can’t fool me. You’re as hungry as I am for something to do.’

Damn the man, he was right. He was wrong, too, of course – men have a powerful drive to simplify matters, and it would be convenient for him to dismiss the side of my life that did not involve him – but as soon as he said it, I could feel the hunger he was talking about, waking in me. I had in the past discovered the immense appeal of a life on the edge of things – walking a precipice, pitting oneself against a dangerous enemy, throwing one’s mind against an impenetrable puzzle.

The waking was brief, as I ruthlessly knocked the fantasy back into its hole. If Dorothy Ruskin had a puzzle, it was not likely to be anything but mild and elderly. I sighed, and then, realising that Holmes was still staring into my face, I had to laugh.

‘Holmes, we’re a pair of hopeless romantics,’ I said, and we turned and walked back to the cottage.

CHAPTER TWO

β

beta

SHORTLY BEFORE MIDDAY ON the appointed Wednesday, I drove my faithful Morris to the station to meet Miss Ruskin’s train. It was four and a half years since we had met near Jericho, and though I would have known her anywhere, she had changed. Her chopped-off hair was now completely white. She wore a pair of glasses, the lenses of which were so black as to seem opaque, and she favoured her right leg as she stepped down from the train. She did not see me at first, but stood peering about her, a large khaki canvas bag clutched in one hand. I crossed the platform towards her and corrected myself – some things had changed not at all. Her face was still burnt to brown leather by the desert sun, her posture still that of a soldier on parade, her clothing the same idiosyncratic variation on the early suffragist uniform of loose pantaloons, tailored shirt, jacket, and high boots that I had seen her wear in Palestine. The boots and clothing looked new, and somehow ineffably French, despite their lack of anything resembling fashion.

‘Good day, Miss Ruskin,’ I called out. ‘Welcome to Sussex.’

Her head spun around and the deep voice, accustomed to wide spaces and the command of native diggers, boomed out across the rustic station.

‘Miss Russell, is that you? Delighted to see you. Very good of you to have me at such short notice.’ She grasped my hand in her heavily calloused one. The top of her squashed hat barely reached my chin, but she dominated the entire area. I led her to the car, helped her climb in, started the engine, and enquired about her leg.

‘Oh, yes, most annoying. Fell into a trench when the props collapsed. Bad break, spent a month in Jerusalem flat on my back. Stupid luck. Right in the middle of the season, too. Wasted half the year’s dig. Use better wood now for the props.’ She laughed, short coughs of humour that made me grin in response.

‘I saw some of your finds in the British Museum recently,’ I told her. ‘That Hittite slab was magnificent, and of course the mosaic floor. How on earth did they make those amazing blues?’

She was pleased, and she launched off on a highly technical explanation of the art and craft of mosaics that went far above my head and lasted until I pulled into the circular drive in front of the cottage. Holmes heard the car and came to meet us. Our guest climbed awkwardly out and marched over to greet him, hand extended and talking all the while as we moved inside and through the house.

‘Mr Holmes, good to see you, as yourself this time, and in your own home. Though I do admit that you wear the djellaba better than most white men, and the skin dye was very good. You are looking remarkably well. How old are you? Rude question, I know, one of the advantages of getting old – people are forced to overlook rudeness. You are? Only a few years younger than I am, looks more like twenty. Maybe I should have married. A bit late now, don’t you think? Miss Russell – all right if I call you that? Or do you prefer Mrs Holmes? Miss Russell, then – d’you know, you’ve married one of the three sensible men I’ve ever met. Brains are wasted on most men – do nothing with their minds but play games and make money. Never see what’s in front of their noses, too busy making sweeping generalisations. What’s that? The other two? Oh, yes, one was a winemaker in Provence, tiny vineyard, a red wine to make you weep. The other’s dead now, an Arab sheikh with seven wives. Couldn’t write his name, but his children all went to university. Girls, too. I made him. Ha! Ha!’ The barking laugh bounced off the walls in the room and set the ears to ringing. We took our lunch outside, under the great copper beech.

During the meal, our guest regaled us with stories of archaeology in Palestine, which was just getting under way now in the post-war years. The British Mandate in Palestine was giving its approval to the beginnings of archaeology as a science and a discipline.

‘Shocking, it was, before the war. No sense of the way to do things. Had people out there rummaging about, destroying more than they found, native diggers coming in with these magnificent finds, no way of dating them or knowing where they came from. All that could be done with ’em was to stick ’em in a museum, prop up a card saying SOURCE: UNKNOWN; DATE: UNKNOWN. Utter waste.’

‘Didn’t Petrie say something about museums being morgues, or tombs?’ I asked.

‘Charnel houses,’ she corrected me. ‘He calls them “ghastly charnel houses of murdered evidence.” Isn’t that a fine phrase? Wish I’d written it.’ She repeated it, relishing the shape of the words in her mouth. ‘And during the war, my God! I spent those years doing nothing but stopping soldiers from using walls and statues for target practice! Incredible stupidity. Found one encampment using a Bronze Age well as their privy and rubbish tip. Course, the idiots didn’t realise their own water supply was connected to it. Should’ve told ’em, I know, but who am I to interfere in divine justice? Ha! Ha!’

‘Surely, though, most of the digs are more carefully run now,’ I suggested. ‘Even before the war, Reisner’s stratigraphic techniques were becoming more widely used. And doesn’t the Department of Antiquities keep an eye on things?’ My rapid tutorial at the hands of one of the British Museum’s more helpful experts at least enabled me to ask intelligent questions.

‘Oh, yes indeed, improving rapidly, things are. Of course, there’s no room for amateurs like myself now, though I’ll be allowed to make drawings and notes when I get back. There’s talk of opening the City of David, really exciting. But still, we get Bedouins wandering in with sacks of amazing things, pottery and bronze statuettes, last month a heart-stopping ivory carving, magnificent thing, part of a processional scene, completely worthless from a historical point of view, of course. He wouldn’t tell us where in the desert it came from, so it can’t be put in its proper archaeological setting. A pity. Oh, yes, that’s more or less why I’m here. Where’s my bag?’

I brought it from the sitting room, where she had casually dumped it on a table. She opened it and dug through various books, articles of clothing, and papers, finally coming out with a squarish object wrapped securely in an Arab man’s black-and-white head covering.

‘Here we are,’ she said with satisfaction as she displayed a small intricately carved and inlaid wooden box. She laid it in front of me, then bent to replace various objects into the bag.

‘I’d like you to look at this and tell me what you think. Already gave it to two so-called experts, both men of course, who each took one look and said it was a fake, couldn’t possibly be a first-century papyrus. I’m not so sure. Really I’m not. May be worthless, but thought of you when I wondered whom to give it to. Show it to whomever you like. Do what you can with it. Let me know what you think. Yes, yes, take a look. Any more tea in that pot, Mr Holmes?’

The box fit into one hand and opened smoothly. Inside was nestled, secure in a tissue bed, a small roll of papyrus, deeply discoloured at the top and bottom edges. I touched it delicately with my finger. The tissue rustled slightly.

‘Oh, it’s quite sturdy. I’ve had it unrolled, and the two “experts” didn’t coddle it any. One said it was a clever modern forgery, which is absurd, considering how I got it. The other said it was probably from a madwoman during the Crusades. Experts!’ She threw up her hands eloquently, eliciting a sympathetic laugh from Holmes. ‘At any rate, the experts deny it, so we amateurs can do as we please with it. It’s all yours. I started on it, but my eyes are no good now for fine work.’ She took off her dark glasses, and we saw the clouds that edged onto the brilliant blue of her eyes. ‘The doctors in Paris say it’s because of the sun, that if I wear these troublesome things and stay inside all the time, it’ll be five years before they have to operate. Told them there was no point in having the years if I couldn’t work, but, being men, they didn’t understand. Ah well, five years will get me going, if I can get the money to start my dig, and after that I’ll retire happy. Which has nothing to do with you, of course, but that’s why I’m giving you the manuscript.’

I took the delicate roll from its box and gently spread it out on the table. Holmes pinned the right end down with two fingers and I looked at the beginning, which, as the language was Greek, began at the upper left. The spiky script was neat, though the whole eighteen inches were badly stained and the edges deeply worn, in places obscuring the text. I bent over the first words, then paused. Odd; I could not be reading them correctly. I went back to the opening words, got the same results, and finally looked up at Miss Ruskin, perplexed. Her eyes were sparkling with mischief and amusement as she looked over the top of her cup at me.

‘You see why the experts denied it, then?’

‘That is obvious, but—’

‘But why do I doubt them?’

‘You couldn’t seriously think—’

‘Oh, but I do. It is not impossible. I agree it’s unlikely, but if you leave aside all preconceived notions of what leadership could have been in the first century, it’s not at all impossible. I’ve been poking my nose into manuscripts like this for half a century, and though it’s somewhat out of my period, I’m sorry, this does not smell like a recent forgery or a crusader’s wife’s dream.’

It finally got through to me that she was indeed serious. I stared at her, aghast and spluttering.

‘Would you two kindly let me in on this?’ interrupted Holmes with admirable patience. I turned to him.

‘Just look at how it starts, Holmes.’

‘You translate it, please. I have worked hard to forget what Greek I once knew.’

I looked at the treacherous words, mistrusting my eyes, but they remained the same. Stained and worn, they were, but legible.

‘It appears to be a letter,’ I said slowly, ‘from a woman named Mariam, or Mary. She refers to herself as an apostle of Joshua, or Jesus, the “Anointed One”, and it is addressed to her sister, in the town of Magdala.’

CHAPTER THREE

γ

gamma

HOLMES BUSIED HIMSELF WITH his pipe, his lips twitching slightly, his eyes sparkling like those of Miss Ruskin.

‘I see,’ was his only comment.

‘But it’s not possible—’ I began.

Miss Ruskin firmly cut me off. ‘It is quite possible. If you read your Greek Testament carefully, ignoring later exclusive definitions of the word apostle, it becomes obvious that Mary Magdalene was indeed an apostle, and in fact she was even sent (which is, after all, what the verb apostellein means) to the other – the male – apostles with the news of their Master’s resurrection. As late as the twelfth century, she was referred to as “the apostle to the apostles”. That she fades from view in the Greek Testament itself does not necessarily mean too much. If she remained in Jerusalem as a member of the church there, which after all was regarded as merely one more of Judaism’s odder sects, all trace of her could easily have disappeared with the city’s destruction in the year 70. If she were still alive then, she would have been an old woman, as she could hardly have been less than twenty when Jesus was put to death around the year 30 – but impossible? I would hesitate to use that word, Miss Russell, indeed I would.’

I drew several deep breaths and tried to compose my thoughts.

‘Miss Ruskin, if there is any chance that this is authentic, it has no place in my hands. I’m no expert in Greek or first-century documents. I’m not even a Christian.’

‘I told you, it’s already been seen by the two foremost experts in the field, and they have both rejected it. You want to send a copy to someone else, that’s fine. Send it to anyone you can think of. Publish it in The Times, if it makes you happy. But, keep the thing itself, would you? It’s mine, and I like the idea of your having it. If you don’t feel comfortable with it, lend it to the BM. They’ll throw it in a corner for a few centuries until it rots, I suppose, but perhaps some deserving student will uncover it and get a D Phil out of it. Meanwhile, play with it for a while, and as I said, let me know what you come up with. It’s yours now. I’ve done what I could for Mariam.’

I allowed the little conundrum to curl itself up and then placed it thoughtfully back into its box with the snug lid.

‘How did it come to you? And the box? That’s surely not first century?’

‘Heavens no. Renaissance Italian, from the style of inlay, but I’m no expert on modern stuff. The two came together, though I added the tissue paper to stop it from rattling about. Got it about four months ago, just before Easter. I was in Jerusalem – had just come back from a visit to Luxor, Howard Carter’s dig. Quite a find he’s got there, eh? Pity about Carnarvon, though. Any road, I had just been back a day or so when this old Bedouin came to my door with a bundle of odds and ends to sell. Couldn’t think why he came to me. They all know I don’t buy things like that, don’t like to encourage it. I told him so, and I was about to shut the door in his face when he said something about “Aurens”. That’s the name a lot of the Arabs call Ned Lawrence – you know, the Arab revolt Lawrence? Right, well, I knew him a bit when he was working at Carchemish before the war, at Woolley’s dig in Syria. Brilliant young man, Lawrence. Pity he got sidetracked into blowing things up, he could have done some fine work. Seems to have lost interest. Oh well, never too late, he’s still young. Where was I? Oh, right, the Bedouin. Turned out this Bedouin knew him then, too, and rode with him during the war, destroying bridges and railway lines and what not.

‘His English was not too great – this Bedouin’s, that is, not Lawrence’s, of course – but over numerous cups of coffee, with my Arabic and his English, it turned out that he’d been injured during the war and now was finding it difficult to get work. A lot of these people are being crowded out of their traditional way of life and have no real skills for the modern world. Sad, really. Seems that was his case. So, he was selling his possessions to buy food. Sounds like the standard hard-luck story to convince a gullible European to hand over some cash, but somehow the man didn’t strike me that way. Dignified, not begging. And his right hand was indeed scarred and nearly useless. Tragic, that, for an Arab, as you know. So I looked at his things.

‘Some of them were rubbish, but there were half a dozen beautiful things: three necklaces, a bracelet, two very old figurines. Told him I couldn’t afford what they were worth but that I’d take him to someone who could. At first, he thought I was just putting him off, couldn’t believe I was not trying to buy at a cut price, but the next day I took him to a couple of collectors and got them to give him every farthing of their value. Amounted to quite a bit, in the end. He was speechless, wanted to give me some of it, but I couldn’t take it, could I? I told him that if he wanted to repay me, he could promise never to be involved with digging up old things for sale. That’d be payment enough. He went off; I went back to my sketches for the dig.

‘About a month later, late one night, he appeared again at my door, on site this time, with another bag. Oh Lord, I thought, Not again! But he handed me the bag and said it was for me. There were two things in it. The first was a magnificent embroidered dress, which he said his wife had made for me. The other was this box. He told me it came from his mother, had been in the family for generations, since before the Prophet came. I knew it wasn’t that old, and he must have seen something on my face, because he took the box and opened it to show me the manuscript. That was what his family had owned for so long, not the box, he said, which had been his father’s. He told me, if I understood him right – he would insist on speaking English, though my Arabic’s better than his was – that it had been in a sort of pottery mould or figurine when he was a child. It broke when he was twelve, and the whole family was terrified that something awful would happen – sounds like a sort of household god, doesn’t it? They hadn’t known there was anything inside the figure. Nothing much happened, though, and after a while his father put the manuscript into a box he had been given by some European. It came to this man when his parents were killed during the war, and as he himself had no children, he and his wife decided to bring it to me. I tried to give it back to him, but he was deeply offended, so in the end I took it. Haven’t seen him since.’

The three of us sat contemplating the appealing little object that sat on the table amidst empty cups and the remains of the cheese tray. It was about six inches long, slightly less than that in depth, and about five in height, and the finely textured blonde wood of its thick sides and lid was intricately carved with a miniature frieze of animals and vegetation. A tiny palm tree arched over a lion the size of my thumbnail; its inlaid amber eyes twinkled haughtily in a shaft of sunlight. There was a chip out of one of the box’s corners, and two of the giraffe’s shiny jet spots were missing, but on the whole, it was remarkably free of blemish.

‘I think, Miss Ruskin, that the box alone is an overly valuable gift.’

‘I suppose it is of value, but it pleases me to give it to you. Can’t keep it – too many things disappear when one is on a dig – and can’t bring myself to sell it. It is yours.’

‘“Thank you” sounds inadequate, but if you wanted to be sure it has a good home, it has found one. I shall cherish it.’

An enigmatic smile played briefly over her lips, as at a secret joke, but she said, only, ‘That’s all I wanted.’

‘Shall we have a glass of wine to celebrate it? Holmes?’

He went off to the house, and I tore my eyes away from the beguiling present.

‘Can you stay for supper?’ I asked. ‘Your telegram didn’t say when you had to be back, and the housekeeper has left us a nice rabbit pie, so you wouldn’t have to face my cooking.’

‘No, I can’t. I’d like to, but I have to be back in London by nine – dinner with a new sponsor. Have to talk up the glory that was Jerusalem to the rich fool. Plenty of time for a glass of your wine, though, and a stroll over your hills.’ She sighed happily. ‘We used to come down to the coast every summer when I was a child. The air hasn’t changed a bit, or the light.’

We took our glasses and walked over the hills to the sea, and when we returned to the cottage, Holmes asked her if she wanted to see the beehives. She said yes, so he found her a bee hat and gloves and overalls, things he himself rarely used. She was at first nervous, then determined, and finally fascinated as he opened a hive and showed her the levels of occupation, the queen’s quarters, the neat texture of the honeycombs, the logical, ruthless social structure of the colony. She asked numerous intelligent questions, and she seemed both relieved and reluctant to see the internal workings disappear again behind their wooden walls.

‘Had a nasty experience with bees one time,’ she said abruptly, and pulled off the voluminous hat. ‘Lived in the country. My sister and I were close then, played lots of games. One was to leave coded messages, in the Greek alphabet sometimes, or little treasures – bits of food – inside this abandoned cistern. Must’ve been mediaeval,’ she reflected. ‘Storing root crops. We called it “Apocalypse”, had to lift the cover off, you see? Happy times. Golden summers. One day, my sister hid a chocolate bar in Apocalypse, went back for it the next day, and a swarm of bees had moved in. Both of us badly stung, terrified. Apocalypse filled in. Seemed like the closing of paradise.’

‘They were probably wasps,’ commented Holmes.

‘Do you think so? Good heavens, you may be right. Just think, all those years of hating bees, dispelled in an afternoon. Didn’t know you were an alienist, Mr Holmes, among your other skills.’ She chuckled.

We made our way back to the terrace, where I served a substantial tea while she entertained us with stories of the bureaucrats in Cairo during the war.

Finally, she stood up to go. She paused at the car and looked over the front of the cottage.

‘I can’t think when I’ve enjoyed an afternoon more.’ She sighed.

‘If you have another free day before you go, it would be a great pleasure to have you again,’ I suggested.

‘Oh, won’t be possible, I’m afraid.’ Her eyes were hidden again behind the black glasses, but her smile seemed somewhat wistful.

The drive into town was slowed by the number of farm vehicles about on a summer afternoon, but I had allowed plenty of time, and we talked easily about books and the uncluttered and unrecoverable pleasures of life as an Oxford undergraduate. Then she abruptly changed the topic.

‘I like your Mr Holmes. Very like Ned Lawrence, d’you know? Both of ’em positively quivering with passion, always under iron control, both stuffed full of ability and common sense and that backwards approach to a problem that marks a true genius, and at the same time this incongruous tendency to mystify, a compulsion almost to obfuscate and to conceal themselves behind an air of myth and mystery. Ned’s extravagances,’ she added thoughtfully, ‘are almost certainly due to his small stature and the domination of his mother and will bring him to a sticky end. He’ll never have the hands of your man, though.’

I was quite floored by this tumble of insight and information so placidly given, and I could only pluck feebly at the last phrase.

‘Hands?’ Was this some idiosyncratic equine reference to Holmes’ height?

‘Um. He has the most striking hands I’ve ever seen on a man. The first thing I noticed about him, back in Palestine. Strong, but more than that. Elegant. Nervous. No, not nervous exactly; acutely sensitive. Aristocratic working-class hands.’ She grimaced and waved away this uncharacteristic search among the nuances of adjectives. ‘Remember the Chinese ball?’

‘The Chinese—oh yes, the ivory puzzle.’ I did remember it, a carved ball of ivory so old, it was nearly yellow. It could only be opened by precise pressure at three different points simultaneously. She had handed the ball to Holmes, and he had held it lightly in the palm of his left hand, occasionally caressing it with the fingertips of the other. (Holmes, unlike myself, is right-handed.) The conversation had gone on; Holmes had talked with great animation about his travels in Tibet and the amazing feats of physical control he had witnessed amongst the lamas, and his tour through Mecca, while he occasionally reached down to touch the ball. The magician’s apprentice knows to watch the hands, though, and I was gratified to witness the gentle arrangement of thumb and two fingers that loosed the lock and sent the ball’s treasure, a lustrous black pearl, rolling gently into the palm of his hand.

‘So clever, those hands. It took me six months to figure out that ball, and he did it in twenty minutes. Oh, are we here, then?’ She sounded disappointed. ‘Thank you for the afternoon, and do enjoy Mariam. I’ll be interested to know what you think of her. Did I give you my address in Jerusalem? No? Oh, dash it – here comes the train. Where are those cards – in here somewhere.’ She thrust at me two handfuls of motley papers – a couple of handbills, some typescript, letters, sweet wrappers, telegram flimsies, notes scribbled on the corners of newspapers – as well as three journals, a book, and two glasses cases (one empty), before she emerged with a bent white cardboard rectangle. I poured the papers back into her bag, took the card, and helped her up into the carriage.

‘Good-bye, my dear Miss Russell. Come see me again in Palestine!’ She seemed on the edge of saying something else, but the whistle blew, the moment passed, and she contented herself with leaning forward and kissing my cheek. I stepped down from the train, and she was gone.

On the way home, I was in time to be greeted by a neighbour’s dairy herd being brought down the narrow lane for the night. I took the car out of gear to wait and looked down at my hands. Competent, practical hands, with large knuckles, square nails, rough cuticles, ink stains, and a dusting of freckles. The two outer fingers of the weaker right hand were slightly twisted, a thin white scar almost invisible at their base, near the palm, one remnant of the automobile accident that had taken the lives of my parents and my brother and had left me with a multitude of scars, visible and otherwise, following weeks in the hospital, further weeks in hypnotic psychotherapy, and years in the grip of guilt-inspired nightmares. The hands on the steering wheel were those of a student who farmed during the holidays, ordinary hands that could hold a pen or a hay fork with equal facility.

Holmes’ hands, however, were indeed extraordinary. Disembodied, they could as easily have belonged to an artist or surgeon, or a pianist. Or even a successful safe cracksman. As a young man, he had some considerable talent as a boxer, though the thought of putting those hands to such a use made me cringe. Fencing, yes – the nicks and cuts he had picked up left only scars – but to use those sensitive instruments as a means of pummelling another human being into insensibility seemed to me like using a Waterford vase to crack nuts. However, Holmes was never one to believe that any part of himself could be damaged by misuse, which only goes to show that even the most intelligent of men is capable of considerable feeblemindedness.

At any rate, his hands had survived unbroken. As Miss Ruskin had seen, his hands were direct extensions of his mind, the long, inquisitive fingers meandering about over surfaces, lightly touching a shelf or a shoe, until without apparent interference from his brain, they arrived at the key clue, the crux of the investigation. His bony hands were the outer manifestation of his inner self, whether they were probing a lock, tamping shreds of tobacco into his pipe, coaxing a complex theme from his Stradivarius, handling the reins of a fractious horse, or performing a delicate experiment in the laboratory. I had only to look at them to know the state of his mind, how an investigation or experiment was proceeding, and how he thought it might turn out. A person’s life is betrayed by the hands, in the calluses and marks and twists of skin and bone. The life of Sherlock Holmes lay in his long, strong, sensitive hands. It was a life that was dear to me.

I looked up, to find the road clear of all but a few gently steaming cowpats, and the farmer’s small son staring curiously at me over the gate. I put the car into gear and drove home.

CHAPTER FOUR

δ

delta

FOR SUCH A SHORT and apparently uneventful episode, the visit of this passionate amateur archaeologist left behind it a disconcerting emptiness. It took a deliberate and conscious effort to return to our normal work, I to my books, Holmes into a laboratory that emitted a variety of odours late into the night, most of them sulphurous, all of them foul. I indulged myself in an hour of deciphering Mariam’s letter before returning to the manly declarations of the prophet Isaiah, waved vaguely at Mrs Hudson’s greeting and later at her ‘Good night, Mary’, and worked until my vision failed around midnight. I closed my books and found myself looking at the box. Whose hands had so lovingly formed that zebra? I wondered. What Italian craftsman, so far from an obviously well-known and beloved African landscape, had carved this piece of perfection? I rested my eyes on it until they started to droop, then picked up the box and held it while I went through the house, checking the windows and doors. I then climbed the stairs.

Holmes did not look up from his workbench, just grunted when I mentioned the hour. I went down the hallway to the bath. He had not appeared when I returned. I put the box on the bedside table and turned off the lamp, then stood for some minutes in the wash of silver light from the moon, three days from full, and watched the ghostly Downs tumble in frozen motion to the sea. I left the curtains drawn back and took myself solitary to bed, and as I lay back onto the pillow, I realised that Holmes had not read the newspapers for at least three days.

The observation sounds trivial, a minor disturbance on the surface of our lives, but it was no less ominous than a stream’s roil that, to the experienced eye, shouts of the great boulder below. Marriage attunes a person to nuances in behaviour, the small vital signs that signal a person’s well-being. With Holmes, one of those indicators was his approach to the London papers.

In his earlier life, the daily papers had been absolutely essential to his work. Dr Watson’s accounts are as littered with references to the papers as their sitting room was with the actual product, and without the facts and speculations of the reporters and the personal messages of the agony columns, Holmes would have been deprived of a sense as important as touch or smell.

Now, however, his newspaper habits varied a great deal, depending on whether the case he was on concerned the politics of France, the movements of the art world, or the inner financial doings of the City. Or, indeed, if there was a case at all. He regularly drove the local newsagent to distraction, and vice versa. For weeks on end, Holmes was content with a single edition of one of the London papers, and the Sussex Express for Mrs Hudson. When he was on a case, however, he insisted on nothing less than every edition of every paper, as soon as it could reach him, and for days the normal serenity of our isolated home would be broken by the nearly continuous arrivals and departures of the newsagent’s boy, a compulsively garrulous lad with skin like a battlefield and a wall-piercing adenoidal voice.

During one of my absences the previous spring, Holmes had inexplicably changed from one of the more lurid popular papers to The Times, which to my mind has always been eminently suited to morning tea and a discreet scattering of toast crumbs. However, The Times is a morning paper, and it has to travel from London to Eastbourne, from that town to our village, and thence to us. It never reached us much before noon, and often considerably later, if the pimply-faced bicyclist had a puncture or encountered a friend.