9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

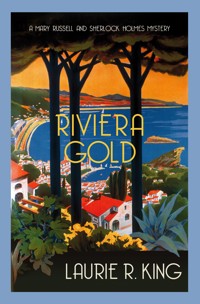

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Mary Russell & Sherlock Holmes

- Sprache: Englisch

It's summertime on the Riviera, where the Jazz Age is busily reinventing the holiday delights of warm days on golden sand and cool nights on terraces and dance floors. Just up the coast lies a more traditional pleasure ground: Monte Carlo, where fortunes are won, lost, stolen, and hidden away. So when Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes happen across the C te d'Azur in this summer of 1925, they find themselves pulled between the young and the old, hot sun and cool jazz, new friendships and old loyalties, childlike pleasures and very grownup sins...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 493

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

3

RIVIERA GOLD

LAURIE R. KING

5

To all the grey-haired ladies out there, filled with wisdom and mischief And yes – to some of the men

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Why had i never considered the possibility that an arms dealer might wield actual arms?

I’d probably assumed that a man who dealt in deadly munitions was only dangerous in the abstract and large-scale – like a battlefield commander incapable of euthanising the family pet.

No: naturally a person like this would have a gun to hand. And no ordinary old weapon, but the sleekest, most modern of automatic pistols. Not that the model made any difference at this range, not when it was pointed directly at my heart.

A child could not miss.

A moment of cold silence washed over me, followed by an absurd tumble of questions. Would it hurt? Yes, it was bound to hurt – but would my mind register the pain, or even the muzzle flash, before 8flickering out? Did the man have any idea who I was? Could he know that pulling the trigger would bring down the wrath of the British government? Did he have any clue that the young woman before him was wife and partner to none other than Sherlock Holmes? Was he really prepared to ruin this spectacular carpet?

—and then I wrenched my thoughts away from idiocy and my eyes off the mesmerising black circle, looking past it into the old monster’s dead eyes.

I cleared my throat. ‘I wonder if we might have a little talk? Preferably before you shoot me.’

CHAPTER ONE

Mrs Hudson: a conversation

April, 1877 – London

The warm air smelt of honey.

The air outside had been sharp with the usual London stinks of horse dung and coal smoke and rain, making the Duke’s townhouse a welcoming refuge. Granted, by the end of the night the pleasure would be reversed, with exhausted, footsore dancers stumbling away from the smell of sweat and the stifling miasma of women’s perfumes and men’s hair oil. But for now, drifting from portico to cloakroom, hallway to the ballroom itself, all was promise and sparkle and the sweet aroma of beeswax candles.

Clarissa, whose escort was bent in some confusion over her dance card, caught the apricot colour of silk in a slice of mirror and took a half-step forward to admire the dress. It was new and expensive – very à la mode, the result of many hours of poring over sketches with the 10dressmaker. The fashion for a long, well-corseted torso suited her, and the lightly bustled train at the back emphasised a woman’s front in a way that would have been judged indecent just a few years ago. The nakedness of her shoulders, front and back, was both innocent and tantalising, and the curve of her hips would, she had learnt, tempt a dance partner’s hands into a drift downward as the evening progressed and the golden candles began to gutter and wink out, one by one.

She reminded herself to be wary of men who had shed their gloves – and not only because of the stains their palms left on silk.

Her thoughts were interrupted by a figure in black, coming towards her in the looking glass. She turned, pleased that here was one acquaintance who might turn into a friend – an actual friend, rather than a useful name or camouflage. (It helped that she was married, and therefore out of the competition.) ‘Dear thing, I was wondering if you’d come. Though how you manage to look so festive and delicious in black, I cannot know.’

The two exchanged near-kisses, and the newcomer shook her head in appreciation of Clarissa’s apricot silk. ‘Speaking of delicious! Oh, I do look forward to getting out of mourning and being permitted to dance again.’

‘When you do, the rest of us will have to work twice as hard to be noticed.’

‘That is not something you need to worry about, my dear Miss Hudson. So what mischief have you got up to, since I saw you last?’

‘Mischief? Me?’

The two laughed, and then Clarissa’s gentleman claimed his dance, and they were away.

The two young women met up again over supper, when Clarissa’s favoured partner and the other woman’s rather boring husband parked 11them in seats, presented them with full glasses, then went off to load plates with tempting morsels.

Clarissa tried to cool her face with a fan the same colour as her dress. ‘A night this warm, I’m a bit envious of your getting to sit at the sidelines. My face must be horrid and red.’

‘Just nicely pink. I’m impressed that you haven’t yet lost bits of your train to some careless set of shoes.’

‘I was stepped on twice, but neither time fatally.’

‘Trains are not the most practical things for the dance floor. So tell me, before the men come back, is there anyone you’re hoping for an introduction to?’

Clarissa Hudson eyed her possible, would-be friend, wondering just how much the woman knew, or had guessed. A married acquaintance could be an asset, since the rules binding women’s behaviour were relaxed the moment a ring went on. She’d even seen some of them smoking! But this one, married or not, was both new to London and an amateur in the sport of playing men. It was hard to judge how far her amusement would go before it turned suddenly to shock – or disdain. Either could be fatal to someone in Clarissa’s position.

Still, even the most innocent of girls would be forgiven a degree of curiosity towards the opposite sex. After all, wasn’t that what the season was for? And she was twenty years old: at the height of her powers when it came to feminine games. ‘I don’t suppose you know that tall gentleman with the striking eyes, speaking with the Earl of Shrewsbury?’ The man was older than they, perhaps thirty, and impeccably clothed from his gleaming blonde head to his polished black shoes. There was an air of vitality about him that promised, at the very least, an interesting conversation.

Plus, everything about him spoke of money.

‘You mean Zedzed? We haven’t been formally introduced, but 12from what I hear, I’m not sure he’s someone you need to know.’

‘Why ever not? And surely that’s not his actual name?’

‘No, it’s from all the zeds in his name – he’s Russian, or was it Greek?’

‘How exotic. But why mustn’t I meet him?’

‘He has some rather dubious antecedents. An embezzlement trial, among other things, a few years ago.’

‘He couldn’t be too bad of an egg, not if the Duchess invited him.’

It was the sort of remark a naive young thing would make – but then, naive was the role Clarissa Hudson was playing these days. Her friend-to-be gave a little shrug.

‘If you think so. I’m pretty sure my husband knows the Earl – I’ll have him bring the two men over for an introduction. Once he’s finished deciding whether I want salmon mayonnaise or chicken.’

While the woman in mourning craned her head in hopes of catching her husband’s eye, Clarissa gazed over her fan at the Earl and his companion. Mr ‘Zedzed’ was really quite good-looking. She was not in the least surprised when he felt her scrutiny and turned those intense, pale eyes on her. But she was surprised at her own reaction.

A shiver ran down her spine.

Other girls would interpret this as a shiver of delight. Other girls would raise their fans and turn to a nearby friend and giggle, taking that physical reaction as the first sign of love.

Clarissa Hudson knew better. Oh, she was well practised at teasing behind a fan, at pretending innocence, at making use of the cloud of nearby girls to tantalise a male – but she also knew that the intensity of that return gaze was a danger sign. Turn away. Easier quarry lay elsewhere.

She sat, pinned by those pale and speculative eyes. The stuffy air closed in around her, cloying and heavy, until she forced her hand to 13reach out for the other woman’s arm, to tell her not to bother asking for that introduction …

Too late.

After that night, Clarissa Hudson was never quite as fond of the odour of honey. 14

VENICE AND THE RIVIERA

May to July, 1925

16

CHAPTER TWO

Venice had been … unexpected.

Not that it didn’t meet my every anticipation. Venice proved every bit as colourful and warm and entertaining as one might wish, taking my memories of past times and piling on a myriad of piquant experiences that would continue to amuse, on into my old age. Venice had been Cole Porter and moonlit adventures, an island of mad women and a community of sun-maddened expatriates. The place had awakened in me a bizarre gusto for cabaret dances, harmless flirtations, and lethargy – all of which I would have sworn impossible mere weeks earlier.

Of course, the serene city on the lagoon was also, in this modern era of 1925, Mussolini’s Blackshirts and age-old corruption – threats that we had brought with us – and a startling revenge that Holmes and I could never have shaped on our own. 18

As I say: unexpected.

Had it not been for the Honourable Terrence Shields-McClintock, a new and almost instantaneous friend, I expect I would have stepped away from the society of Lido sun-worshippers without a thought, grateful to escape back into my normal world.

(Not that my normal world existed any more. Nothing awaited me in my Sussex home but solitude and the hum of beehives in the orchard. Holmes was off on some unlikely task – yes, that is The Holmes, Sherlock Holmes, my teacher-turned-partner-then-husband – while our housekeeper, Mrs Hudson, the very heart of the home, was … Oh, Mrs Hudson. Beloved and comforting presence, gone away, perhaps for ever.)

As we lounged on the Venice Lido one day in early July, the Hon. Terry had interrupted these sad and pointless thoughts. ‘You need to come sailing with us. Truly.’

I adjusted my sunhat against the rays. ‘Terry, I’ve spent the past two weeks in a series of increasingly odd watery excursions, from gondolas to speedboats—’

‘Stolen speedboats.’

‘—borrowed speedboats to – God help me – skis on top of water. If I don’t go back to the mainland soon, what form of transport might be next? Saddling a gargantuan seahorse? Donning artificial gills? In any event, why would anyone revert to an outmoded form of transport that takes weeks to arrive at a place one can reach by train in a day?’

‘Because you’ll never get the chance again, not on a sweet boat like the Stella Maris.’

‘I’ll probably never get the chance to enjoy frostbite on Everest or being eaten alive by dingoes in the outback, either. Yet somehow I manage to live with the knowledge.’

‘She’s a stunning piece of work, is the Stella. Far too good for her owner.’ 19

‘Who is going as well.’ I’d met the man. Digby Bertram Wellington-Johnes (‘Call me DB – all the gels do!’) was such a stage version of English colonel, from hearty laugh to veined nose to long-out-of-date slang, that I kept waiting for him to give himself away by a wink. The most interesting thing about him was why on earth he’d decided to buy a sailing boat rather than a country house with a hunt nearby. A story he’d started twice in my presence and had never got to the end of.

‘Oh, he’s not a bad sort. A smidge dull, granted.’

‘A smidge? The man makes a dishrag seem exciting.’

‘Well, yes. But there’ll be great food. And you do like the others, and the Italian coastline is just smashing, and there’s loads of interestin’ ports along the way.’

‘Terry, I get seasick.’

‘So we’ll put you up at the prow. Or you can work the rigging, that’ll take your stomach’s mind off things.’

‘Crews never let guests do any of the actual work.’

‘This crew does – I know the captain, he’s happy to shout orders at anyone.’

‘Really?’ Hard, mindless labour did sound more appealing than watching waves go past. (Or listening to an empty house creak and settle.)

‘I posalutely guarantee it. And when we get there, you’ll be just shockingly fit and brown, so burstin’ with human kindness that you could lose it all in Monte and just smile as the croupier hauls away all your lovely lolly. That’s the voice of experience, don’t you know?’

One key word in the deluge reached out and tugged at my ear. ‘Did you say Monte? As in Monte Carlo?’

‘Didn’t I say? We’re headed for the Riviera.’

‘You didn’t, no.’

‘Well, we are – or DB is, at any rate. And yes, it’s the very same 20Monte. Den of iniquity, the principality of pauperdom, city of suicides. Then again, it’s also where Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes has set up. And the Princess Charlotte’s a charming girl.’

‘Who?’

‘Heir to the throne? She and her husband run the place while her father the Prince is off in France. They’ve got the bit in their teeth, going to bring Monaco into the modern age.’

‘You don’t say.’

For a man whose intellectual achievements consisted of memorised poetry, the Hon. Terry could be remarkably perceptive when it came to people. Something in my response betrayed my weakening, and he was on it in a flash. ‘Aha – Monte Carlo, so Mrs Russell has a secret vice! Do we have to keep you from the tables?’

‘I doubt it. I’ve never seen the appeal in setting fire to a lot of banknotes. No, it’s that I have a … friend, who may be living there.’

‘Oh, jolly good! Any friend of yours is bound to be a ripping gal. She is a gal?’

‘She was once.’

‘So it’s settled. Yes? You’ll come a-sailin’ with us?’

He might have been a spaniel begging for a thrown stick. Still, I had to admit it was tempting. As he’d said, how often does one meet the opportunity to circumnavigate Italy on a spectacularly lovely sailing yacht? The dullness of our stage-colonel host would be counteracted by the surprisingly amiable company of the Hon. Terry and his friends. And if the weather turned, if the company palled, if seasickness, rich food, or the steady diet of lotos gave me indigestion, there would be any number of ports along the way that would provide an escape home.

‘Oh, all—’

He did not let me finish, merely shouted in glee and threw his 21arms around me, so impetuous a gesture that it brought with it a flash of my long-dead brother.

And so I had said goodbye to my husband and set off on the Stella Maris with the Hon. Terry and friends; twenty-two days of education in the subtle interactions of canvas and rope, tide chart and compass. I spent my days learning the language of wind in the sails and water in the seas, while scrambling to carry out orders. I spent my nights shovelling down huge servings of delicious food, then falling into my bunk to sleep like the dead. My hands blistered and went hard, my skin burnt and went brown, while I learnt about pulling in partnership, the proper way to throw my weight around, and just how deadly a gust of wind could be. When we were under sail, I was never entirely free of seasickness, but I did find that when I was busy enough, or exhausted enough, I could ignore it.

One night when we were halfway up the Tyrrhenian, with Sicily behind us and the outline of Sardinia yet to appear, it came to me that I had been quietly learning other lessons as well, from this man with no more intellect than a retriever. The Hon. Terry was teaching me about friendship.

I had no family, other than the one I had made through Holmes. My few friends were from university, since I’d somehow never found the time to create more. But on board the Stella Maris, distracted by aching muscles and thirst and hunger, the bursts of shared laughter and effortless camaraderie opened my heart.

In turn, I found I was ever more impatient for the end of the voyage – or rather, for the person I hoped to find there.

It was ten years since the cool, wartime morning in 1915 when I stumbled across Mr Sherlock Holmes on the Sussex Downs. Ten years since the afternoon I’d met the woman who would become my surrogate grandmother. Mrs Hudson called herself a housekeeper, but from that first day, she was so much more.

In all the decade that had followed, all those long years when I 22came to know her worn hands, ageing face, and greying hair better than I knew my own, I never suspected that the heart beating under those old-lady dresses and old-fashioned aprons might belong elsewhere. Never suspected that she had been anything but a landlady-turned-housekeeper – until the past May, when a case brought to light a colourful, even shocking history. The history of a woman named, not Clara Hudson, but Clarissa. A history that came to claim her, and drove my Mrs Hudson from her home.

The thought of losing her had been more than I could bear. I pleaded to know where she was going, how she would get along, what she would possibly do without us. Her reply was less an answer than a vague observation – but as a straw, I would continue to grasp it until it crumbled.

It had been night. The motorcar that would take her away had been idling at the front door, and Mrs Hudson had paused in the act of pulling a pair of travelling gloves over those work-rough hands to consider my question. When she’d looked up, she had not looked at me, who loved her, nor at Sherlock Holmes, who had lived with her for more years than I had been alive. She had not even run her eyes over the doorway that she had polished, swept, and walked through for the past twenty years. Instead, straight of spine and with no sign of hesitation, she had lifted her head to gaze resolutely out into the darkness.

‘Do you know,’ she’d said thoughtfully, ‘I’ve always been fond of Monte Carlo.’

CHAPTER THREE

Twenty-two days after making our way out of the Venice lagoon, the Stella Maris was sailing, not alongside a coastline, but towards one. I was every bit as trim and brown as Terry had promised. Also, perpetually hungry, always thirsty, and profoundly tired of an endlessly moving deck beneath my feet.

Tired, too, of some of my fellow passengers – not Terry’s friends, but those of our host, DB. As a group, their humour was heavy-handed, their conversation patronising, and they proudly demonstrated their wit by using quotes that were either stale, or inapt, or simply wrong.

Such as DB’s proclamation now, as we drew near the Riviera coast: ‘And in the afternoon they came to a land where it was always afternoon.’

Terry and I winced, as if we’d heard an ill-tuned piano. I waited for Terry to continue the quote – with words Tennyson had actually written. 24

‘All round the coast the languid air did swoon, breathing like one that hath a weary dream,’ he dutifully supplied.

‘Wrong time of the month for a full-faced moon, though,’ I noted. This, too, was part of the ritual, the two of us joining forces in the subtle mocking of ignorance.

It was probably a good thing we planned to disembark soon, before our mockery grew shameless. I gave DB a smile that I hoped looked friendly rather than apologetic, and went below to shove the last things into my valise. Terry followed, standing with his shoulder propped against the doorway.

‘So, have you thought about stopping with us for a bit?’ he asked.

I pushed my unruly hair out of my eyes, wondering where I had put my scissors. ‘Terry, you must be truly sick of me.’

‘Mary Russell, I don’t know what I’ll do when you leave! Who else understands my jokes?’

I put on a puzzled expression. ‘Terry, have you been making jokes?’

‘Har har.’

‘Your friends laugh. More than I do, really.’

‘Patrice laughs when he knows it’s supposed to be a joke, and Luca laughs because he doesn’t want to admit he missed it in English. Oh, do come along, just for a couple of days. It’ll be a new experience to talk to people without watching their heads bobble with the waves.’

‘Oh, I couldn’t. The people you’re staying with will be plenty crowded with the four of you.’

‘No, we’re at a hotel.’

‘Really? What kind of Riviera establishment is open in midsummer?’

‘Most of ’em do close – this one did, until a couple years ago. But the more guests they can pull in, the better the chance they’ll keep it open next year.’

‘Why on earth would they want to?’ 25

I got to my knees to check under the bunk for stray pens and wayward stockings, half listening as Terry prattled about a note that caught up with him in our last port, from a friend extolling the virtues of summer holidays on the Cap d’Antibes. It seemed that the hotel there, which for its thirty-some-year history had indeed sensibly closed its shutters for the summer season, was recently talked into staying open by a handful of mad Americans with deep pockets and a perverse affection for broiling under the sun. They paid well, but considering the hotel’s plenitude of rooms, it would help, as Terry said, to round up a few more paying guests.

So: extend my leisure holiday, or return to empty Sussex?

First, the obvious question. ‘Who else is coming?’

‘Luca, Patrice, and Solange,’ he said promptly. His sailing friends – but none of DB’s abrasive guests. Luca was a pleasant young man Terry had taken up with in Venice. Patrice was a friend from Terry’s university days, and Solange, his wife. The five of us had contrived to give the slip to the Stella’s other passengers in nearly every port we’d visited.

I laughed. ‘Then yes, I’d love to join you in a half-deserted, baking-hot, off-season hotel. Though just for a day or two. I do have a life to return to.’

‘Books,’ he said dismissively. ‘Rot your brain.’

Terry knew nothing about my other life – the real one, with Sherlock Holmes. In Venice, people had known my husband as ‘Mr Russell’, amateur violinist, in a bohemian sort of marriage to a much younger and somewhat idiosyncratic bluestocking. Which were not difficult roles to play, since we were both precisely (if not exclusively) that.

One night on the Stella Maris, under the spell of moon and friendship and more than a little alcohol, I had come near to blurting out the truth. Solange had been reading a detective story, and the others began proposing alternative solutions to the mystery. The name Holmes was on 26the very tip of my tongue – until Terry said something jolly that made me actually picture him in an investigation: stepping in the footprints, pocketing a vital clue, and refusing to believe that one of his friends could do anything so dashed unsporting as commit murder.

At that, I remembered the threat of endless prying discussions about the mythic, near-fictional character Sherlock Holmes, and firmly shut my mouth.

But despite the mild effort of keeping up the act, spending a day or two on the French coast was not a bad idea. If nothing else, it being a land of Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, and Ligurians meant that it would provide any number of aqueducts, amphitheatres, rural museums, and quaint villages for me to visit. It would give my muscles time to recuperate, and give me a chance to let Holmes know where I was. And yes, to see what I could do about locating Mrs Hudson in the nearby principality of Monaco.

Of course, it was always possible that the straw I was so eagerly grasping at was a complete delusion. That the word ‘fond’ had been not a hint, but a vague reflection, or even a deliberate ruse. That our housekeeper with the racy history had in the end gone to another place altogether.

The Stella Maris was headed to Cannes, a few miles along the coast, but the captain put in first to the more workaday harbour at Antibes, to take on fresh provisions for lunch. This was convenient for us – doubly so, because enough fishing boats were out at sea that we were given a berth at the docks rather than having to be tendered ashore. As usual, the boards underfoot seemed to sway more than the boat had, so I paused to make a nonchalant survey of the view while my equilibrium ceased its spinning and grabbing at non-existent walls.

The view was worth admiring. To the south, a piece of rocky land 27extended out into the appropriately azure water. Along the eastern horizon lay the long line of the Alpes Maritimes, while north of the harbour stood the high, stark walls of a castle. The town itself was a typical Mediterranean jumble of red-tiled roofs, smelling of dust and fish.

Terry paused beside me to study the rocky promontory south of town. ‘That might be the Cap d’Antibes.’

‘Didn’t you say there was a beach?’

‘P’raps it’s on the other side.’ He turned his sunglasses at the waterfront road. ‘You see anything that looks like a hotel car?’

The hotel car proved to be two ancient taxis with five good tyres and a pair of unbroken headlamps between them. Those who were staying on the Stella Maris thought this was hilarious, but the affection between DB and Terry, a bit strained during recent days, returned as we took our leave. They waved us off, we waved them good sailing, and we piled into the taxis as the drivers, cigarettes hanging from their lips, tossed the last bags and valises in on top of our sweating bodies, strapped Terry’s new and peculiar-looking skis onto the roof, and ground their motors into gear.

We stopped three times along the way: the first time to let Luca out to be sick (the previous night had been a raucous one on board); the second time while a small boy herded some goats across the road; and the third time for what remained in Luca’s stomach.

The promontory we had seen from the harbour was indeed the Cap, although the larger part of it was hidden from view. The Hôtel du Cap proved to be on its far side, set in a cultivated pine forest overlooking the Mediterranean. A palm-lined entrance drive led to an establishment both large and grand – more luxurious than I had expected.

During the winter, I had no doubt that its halls would ring with the accents of those escaping the cold of the European north and the American east. Now, in the sweltering heat of midsummer, the voices 28inside the doors were a mere echo of its high-season glory. Luca, for one, welcomed the relatively cool silence, and was quickly ushered away to our rooms, as were our bags. The skis did cause the porter momentary puzzlement – not only were they strangely wide, but July was not the usual time for hotel guests to take a jaunt up into the Alps. However, any luxury hotel is accustomed to the peculiarities of guests, so the man merely checked that Terry did not wish to keep the skis in his room, and took them away.

When the lobby was empty again, Terry suggested we take a look at the sea. The four of us wandered through the grounds to the centre of the summer merrymaking, and looked down.

‘Good heavens,’ I said.

The hotel was on top of a cliff, but it had embraced its rocky setting – and got around its lack of a beach – by gouging a large swimming bath into the cliff itself. Above the pool stretched a brilliant white pavilion with arches and shades, stairs leading down to the open sea below. Halfway along the stairs lay the pool and its terrace, the geometric edges making for an odd contrast with the organic stone, although the people below – be they splashing, drinking, or lounging on poolside chaises, fully exposed to the beating sun or sheltering under the striped umbrellas – seemed untroubled by the unnatural symmetry. For those who wanted actually to swim, diving boards thrust out into the open sea, where floating platforms were decorated with lounging figures.

The hotel was where Edwardian formality lay. Outside, it was all Twenties.

Solange declared her intention to don her bathing costume and join them. Patrice amiably agreed to accompany his wife (they were newly wed, so he tended to be amiable about most of her demands). To my surprise, Terry was less enthusiastic, merely telling his friends that he’d see them in the bar later. 29

When they had trotted off to chivvy the maids into digging their costumes from the trunks, he turned to me. ‘Fancy a walk?’

‘Absolutely. Though I may need a hat.’

I had lost five hats on the way from Venice, since the wind on board a ship will pluck off all but the most robustly anchored headgear. Here it was not only dead calm, but uncomfortably hot, without a breath stirring the leaves.

‘You might want a towel, too,’ he said. ‘In case we find that beach.’

So I fetched my surviving hat, and a towel. Also a large silk Venetian scarf under which I could shelter, a flask of water to stave off dehydration, and – need I say it? – a book.

CHAPTER FOUR

The cap d’antibes may once have been a place of thistles and desolation, but at some point in the past century this wilderness had been claimed by the rich. As a result, villas had sprouted, tropical gardens were coaxed into existence, and narrow lanes were lined with the gates of winter homes. The afternoon was quiet, the sun baking our shoulders until we dropped down onto the northern slope, and even then, the path Terry and I described wove back and forth to take advantage of any overhanging trees.

Fortunately, there was little traffic.

In the end, we came to a beach, a pale gold crescent of sand between a low stone wall and the blue waters of a little bay. Where the right-hand point of the crescent faded into trees, some skiffs were tied. Closer to hand was a cafe – but it was shut for the season. 31

‘Perhaps,’ I suggested as we sidled into a patch of shade, ‘three in the afternoon is no time to linger under the Riviera sun.’

There was one person in sight: a man dressed in baggy linen trousers, a striped French jersey, and cloth espadrilles. His head was bound with what looked like a large bandage, although I thought it was probably a way to keep the sun off his scalp.

He was wielding a rake, shifting washed-up seaweed towards the far end of the beach.

Not that the solitary labourer was the only evidence of life. Further along the sand – the nice, well-raked sand – were indications that people had not only been here, but planned to return: a festive blue-striped changing tent, half a dozen leaning beach umbrellas, some sand-covered bamboo mats, a picnic basket. A pile of inner tubes, water wings, the bloated shape of a blow-up rubber horse, half a dozen buckets and some small shovels testified to a family. Either that, or the raking gentleman planned to top his pristine surface with a sandcastle.

Terry studied the signs of civilisation, then ran his eyes along the rest of the beach. All the way down to the groundskeeper, the sand was clear. After his bent figure, a strip of seaweed had been left by the receding tide. I made a small wager with myself as to what Terry would do …

And won.

‘Let’s get you settled,’ he said, ‘and I’ll have a word with that chap. He might know when people will show up again. And anyway, seems a bit rude to take advantage of his work without giving him a tip.’

‘Terry,’ I said, ‘you are a very nice man.’ It was hard to see beneath the dark lenses and hat brim, but I could tell he was blushing.

I spread my towel on a bit of the sand, arranged the scarf as a personal tent, took a swallow of already warm water, and opened my 32book. Tiny waves lapped. Seagulls bickered. I watched the pantomime drama unfold down the way.

Terry had set off under the assumption that the man in the headcloth was a groundskeeper, hired to clear the sand each day. I noted that this work would be less Sisyphean here on the placid Mediterranean than on an English beach, where a day’s tides may rise and fall twenty feet.

The man with the rake turned at Terry’s approach. Terry stopped to ask a question about the missing family, one hand sketching a gesture towards the tent and mats. The stranger replied. There was an exchange of some kind, then Terry’s posture went straight as he registered surprise. A moment later, the two men were shaking hands, and the other fellow leant on his rake handle while Terry assumed his familiar happy-retriever stance.

So: not a hired groundskeeper, but an off-season resident of one of the villas. Most probably the one that Terry had been told to look up, by a mutual friend.

It was a cycle I had witnessed at least a dozen times since meeting the Hon. Terry, the easy shift from stranger to chum through shared interests, friends, boarding school, or some distant blood relationship.

I took another swallow of water and turned a page. From time to time, I glanced at my companions. The man with the rake resumed his labours, Terry keeping him entertained with talk. The band of sea-wrack grew shorter, the conversation more animated. When the two men turned to come back up the now-spotless beach, they walked as brothers.

I tucked in my bookmark and stood to meet my inadvertent host. Terry trotted forward in his eagerness.

‘Mary, this is the very chap I was ordered to hunt down here! Ain’t that a sign it was meant to be? Gerald, this is Mrs Mary Russell, a friend from Venice. Mary, meet Gerald Murphy, an artist and a gentleman.’ 33

I knew him for an American even before he spoke, from the way he pulled the brief headcover from his thinning hair and extended his hand.

‘Russell? And you’ve been in Venice – say, I think I know your husband. Doesn’t he play the violin?’

‘That he does,’ I said in surprise. Not many people in the world thought of Sherlock Holmes as a musician.

‘Then I met him last month at Cole’s place – Cole Porter?’

‘Oh, of course! Very pleased to meet you, Mr Murphy.’

‘Please, call me Gerald. Your husband and Cole spent days putting together music for a “do” at Cole’s palazzo. And Terry here says he crashed that party, but what with half the people in masks and drink flowing like the canal outside, I have no clue if we actually met. Sara and I were still pretty high when we left Venice the next morning,’ he added with a laugh.

My relief at this close call made my greeting effusive. ‘Oh yes, that was quite a night! And thank you for sharing this lovely patch of sand with us. Though I’m afraid the next tide will bring your labours to naught.’

‘It’s not our beach, we just camp out here. As for the seaweed, raking’s a kind of meditation. The first clear-up of the season is a job, but after that it’s like shaving, or cleaning your brushes after a session. The world is fresh and clean, water meeting sand, a blank canvas ready for life.’

Murphy was a likeable sort, friendly and confident without feeling in the least pushy. His smile was easy, his accent was Boston modified by an Ivy League education – Yale? – and some years in Paris.

‘You’re an artist, then?’

‘I paint a little.’

I found myself smiling back at him as I gestured at the empty mats behind me. ‘It looks as if your colleagues on the canvas of life have abandoned you, at present.’ 34

‘The children rest in the afternoon. Some of the grown-ups, too, for that matter. They’ll all be back when the sun is lower. In the meantime, can I offer you two some shade and a drink? Warm, I’m afraid, but better than sea water.’

Terry and I gathered our things and followed our host to his empty encampment, where we sheltered gratefully beneath the striped umbrellas and accepted, with a degree less enthusiasm, beakers of tepid sherry from a half-empty bottle he took from the picnic basket.

The drink was just as disgusting as one might imagine, although Terry manfully slugged his down. Murphy seemed not to notice the temperature, but sipped his as he embarked on the required circuit of small talk that served to identify one’s place in the world and how – not if – the two of us might be related. And indeed, eventually (though not that day) he and I did discover that we were distant and much-removed cousins, linked by various people who infested America’s tightly knit society from Boston to Philadelphia.

That afternoon, however, I mostly sat and counted the waves while the two men performed the ritual, exclaiming at a series of links and overlaps in their worlds. They then moved to interests, seeking out common ground. Terry – who compensated for his sickly childhood with an adult passion for adventure and speed – told the dubious American about our adventures in waterskiing, how he and I had introduced the sport to the Lido set, using a pair of standard Alpine skis, and how he was looking forward to trying out the wider blades he’d had made in Venice. Murphy, intrigued, said he had a friend with a speedboat who might like to learn.

It then being Murphy’s turn, he proceeded to tell his two politely uncomprehending English guests about the growing enthusiasm of artists and writers for the South of France during the summer. We nodded, mopping the sweat from our faces, and drank some water. 35

At last, the two men settled on their common interest in fast machinery, burbling happily along about speedboats and the requirements for pulling skis, racing cars and the recently reintroduced Monte Carlo Rally, and seaplanes and the thrill of the Schneider Trophy, scheduled for another run in October.

Thinking that I ought to contribute in some minor way to the exchange, I asked about said trophy – and then had to do nothing but nod and make noises for a good twenty minutes, as the two told me all about this race for seaplanes that had begun up the coast in Monaco before the war, only to be won and taken away to Italy, followed by Britain, and now the United States.

‘Hmm,’ I said. ‘Really? Imagine that!’ An aeroplane flew over, too high to see if it had pontoons. The tide continued to recede, the line of shadow from the hill behind us crept across the sand – and eventually, we heard voices.

Murphy’s face lit up and he scrambled to his feet.

‘Here we are,’ he declared, as a caravan of people spilt out onto the sand, separating into two directions as they did so. Half a dozen small, noisy individuals with sun-bleached hair raced directly down to the water, trailed by a young girl in daringly short trousers and an older woman wearing a rich blue dress and wide-brimmed hat. The others came towards us – apart from one slim young man wearing clothes ill-suited to an afternoon on the sand. This one called something at the back of the two nannies, lifted his hat in our direction, and turned to leave.

The glimpse offered by that brief salute was of a striking, even beautiful young man. His features were as perfect as a Hellenistic sculpture, with olive skin, curly hair, and startling green eyes that seemed to glow from within. I wanted him to join us – a sentiment that Gerald Murphy clearly shared. 36

Gerald cupped his hands to call across the intervening sand. ‘Niko – come and meet some new friends!’

But the figure merely sketched an apologetic gesture to the world at large, as an indication that his presence was required elsewhere, then tipped his hat again with a graceful bow and walked away.

Gerald chuckled. ‘He never joins us on the beach. I don’t know if he doesn’t like sand, or just doesn’t want to spoil his shoes. Course, he might be busy – some people do actually earn a living.’

‘Who was that?’ I asked.

‘Greek guy named Niko Cassavetes. He’s a friend of – well, everyone, I suppose. Really nice, incredibly helpful to newcomers along the coast. He even managed to put together a fireworks display for us Yanks – but of course, the moon was so bright on the Fourth, he talked us into waiting till Bastille Day. Really impressed the locals – I think the whole population of Antibes was lined up at the harbour that night. Except for some of you Brits. Anyway, you’re sure to meet Niko, sooner or later.’

The others had continued down the beach in an attitude of triumphal procession, many of them carrying some kind of basket or crate. At their lead was a woman of quiet dignity, wearing a long dress of such timeless fabric and design it might almost be called folkloric.

‘I thought for a minute Niko might actually join us,’ Gerald told her, relieving her of a fabric-draped straw basket.

‘He said he had an appointment, but he also has a new pair of shiny shoes, which may have been more to the point. Hello,’ she said, aiming a welcome at Terry and me.

‘This is my wife, Sara,’ Murphy told us. ‘Sara, this is Mrs Russell and Terry McClintock. Terry’s the fellow Didi was talking about – remember her cousin, the Honourable? Turns out they were at that bash Cole and Linda put on last month in Venice, the “Come as your Hero” one, 37though we’re pretty sure we didn’t meet. Oh, but Mrs Russell’s husband was Cole’s partner, the guy with the violin!’

‘Oh yes!’ Sara exclaimed. ‘Cole loved that. Great to meet you at last, Mrs Russell.’

‘And I should thank you, for allowing us to share in your shade.’

‘She was polite over the warm wine I handed her,’ Murphy told his wife. ‘But she’ll be glad for a cold one to replace it.’

Sara then held out her hand to Terry. ‘A pleasure to meet you, er, Sir Terry?’

‘Oh f’reavens sake, I’m no more honourable than the next man. Call me Terry.’

Sara Murphy was a natural beauty with a direct, compelling gaze and a tawny mop of hair, as inviting as the warm sea waters. ‘And Mrs Russell – welcome to our gipsy camp.’

A man would fall in love with this woman, I thought, and fling himself at her feet. I was not unaware of the impulse, myself. ‘Call me Mary,’ I urged, and was rewarded by a smile like a blessing.

Baskets were opened, drinks poured, fruit and biscuits distributed, gay toasts made to friends old and new. The people around us were, if not as stunning as the elusive Niko, nonetheless an extraordinarily handsome group, golden with the sun and eager to absorb Terry and me into their midst. Most were American, and most were a good ten years younger than Gerald and Sara.

Rapid-fire introductions were made, to Rafe and Zelda and John and Olga and a couple of others whose names flew past me, comprising a novelist, a dancer, two artists, an actress filming in Nice, and her lover collected along the way. Sand was shaken from straw mats and travelling rugs, seats were taken, drinks poured – for a couple of the newcomers, conspicuously not their first of the day, or even their fifth. The actress had her male escort cover her with coconut oil, then pushed 38down the straps of her bathing costume so as not to have unsightly pale lines, and arranged herself on a mat to bake. Down the beach, the two nannies folded the children’s discarded garments into neat piles and stood chatting, backs to the adults and eyes on what seemed like a large number of small splashing bodies.

Sara was explaining to Terry and me how they came to be here – and yes, the Murphys were indeed those mad Americans who had coaxed the Hôtel du Cap into remaining open during the quiet months, two years earlier.

‘Paris is so awful in the summer, don’t you think? But Antibes – this place is just paradise. All we have to do is talk our friends into coming down to visit, which hasn’t proved too hard – the Train Bleu is such a treat – leave Paris at dinner and have lunch in Antibes. And now that Gerald and I have our own house – we’ve just finished the renovations, praise be! – we can even offer people a place to stay, or work. You’ll come to dinner tonight, both of you.’

‘That’s a lovely offer, Mrs Murphy—’ Terry started.

‘Sara. None of us are formal here.’

‘A smashing offer, but I promised my friends that I’d join them for dinner, back at the hotel.’

‘Bring them along! We adore new people, and there’s plenty of food. Unless they’re horrible and boring, that is.’ Her smile let us know that she refused to believe either of us could have anything to do with such a creature as a boring human being.

‘No, all three of them could charm the monocle off Joe Chamberlain. Couldn’t they, Mary?’

I nodded. ‘Having spent the past weeks living in one another’s pockets, I cannot say I was ever bored.’ Shocked, perhaps, and often baffled, but not bored.

That led to a question of how Terry and I came to appear on the 39beach together, which led to the Stella Maris, then back to Venice and the Porters and another set of mutual friends and distant cousins. As before, I was happy to let Terry take the lead with this recitation, since my own history, unless tightly edited, would inevitably lead to those same Sherlock Holmes discussions I had thus far managed to avoid. The conversation followed the track of waterskiing, then motorcars, and splintered into two or three separate groups.

Three of the gathering – Zelda, Olga, and the lover – were talking about dancing, although the desultory pattern of their talk suggested that the two women were tired of each other. The actress and Terry debated recent films. Two of the men argued about art – a sculptor who was not dressed for the beach and clearly found sand in his shoes irritating, and a young painter who rarely got to finish a sentence. Sara lay paging through a tattered copy of Mrs Beeton and making notes. She and her husband participated in all three discussions, tossing in the odd remark and directing things away from troubled waters.

I allowed Murphy – Gerald – to fill my glass again, and ate a biscuit as I watched the antics of the six happy children.

Sara Murphy noticed the direction of my eyes. ‘Do you have children, Mary?’

‘My husband has a grown son and a granddaughter we see whenever we’re in Paris.’ I blinked in surprise. It was not a reply I usually gave, even to friends, since it invariably led to the further question of whether I wanted children, and why I did not have them, neither of which were easy to answer.

Fortunately, either Sara was more sensitive than most, or she had learnt that it is better to let a person walk through a conversational door than try and drag them through it. ‘How sensible of you – a ready-made family without the teething and toilet training.’

I laughed, and she went back to her Household Management. My 40gaze wandered down again to the splashing figures, without whom the little cove would have seemed strangely empty.

What would it have been like to have had a childhood of bare limbs and sun-warmed sand? I wondered. My own memories were of scratchy woollen bathing costumes, compulsory parasols, and being dragged off to shelter the moment the sun grew high. Unlike those golden bodies, flailing and chattering and pausing to examine some bit of aquatic wildlife. Paradise, indeed … and I would not think about the fact that the biblical inhabitants of Eden soon met a snake.

One of the smaller children, young enough to be uncertain on her feet, sat down hard in the water and began to wail. The nannies took this as a signal to gather the three youngest charges, retrieve the piled garments, and make their way to the adult gathering and the snacks that lay at hand. Near the mats, the children split up – a boy of about five with sun-bleached hair to Sara, a girl slightly younger claiming Zelda, while the other child, of uncertain sex, stayed with the young woman in the short trousers.

Small hands were brushed off and filled with biscuits, small hats untied and removed, then all three round little bodies were plunked down inside the striped tent where the slim young nanny took out a picture book. The older woman, tasked with keeping her eye on the remaining children, settled onto a beach chair facing the water. Gerald took her a glass of wine and shifted one of the umbrellas so she was out of the sun. She murmured a thanks, and took a deep swallow from the glass before working its base into the sand.

The groups had shifted: sculptor and actress now discussed a film, Sara was chatting with Olga about a recipe, Zelda was flirting with Terry. Gerald and I talked about sailing boats for a minute, then he turned to the stray lover to ask about Cannes, leaving me free to think my thoughts. After a minute, I tried settling down 41into the travelling rug, wriggling my shoulder blades to create a comfortable hollow in the sand. My legs were in the sun, but the umbrella shaded me from the waist up. I found that if I rested my glass on my stomach, I could take a sip by merely raising my head.

I was, in short, indulging that unexpected taste for lethargy.

The older nanny’s dress, I thought drowsily, was quite a pretty colour – the blue of the deeper waters off the coast. I wondered what its neckline looked like. (She had her back to me.) Something about her was vaguely familiar. The set of her shoulders. Perhaps I’d seen her earlier, among the chairs at the hotel’s pool?

As if she’d heard the thought, the woman seemed to take a deep breath. Her manicured fingers rose to untie and pull off the sunhat, revealing the back of an attractive haircut, unabashedly grey but fashionably modern. She took another sip of wine, returned the glass to the sand, and braced her hands on the arms of her chair. I thought she was going to walk down and speak with the older children. Instead, her shoulders turned as she swivelled in her chair. Her face came into view.

And my glass flew into the air.

Mrs Hudson.

CHAPTER FIVE

Mrs Hudson: a conversation

Eleven weeks earlier

The lady of the house opened the door herself, and swept onto the sun-washed street to embrace her long-awaited guest. ‘Clarissa Hudson, oh my darling thing! I never thought this day would arrive – come in, you must be exhausted. Mathilde, dear, have the driver carry her things in, then we’ll take tea in the garden. We’ve put you in your usual room, Clarissa, the one with the harbour view. Oh, it’s so good to see you. When I got your cable last week I danced for joy – positively skipped across the carpet, didn’t I, Mathilde? Though on the telephone you did sound just a touch down. My, what a delightful frock, it does marvellous things for your eyes. Paris, yes?’

‘Where else? Ah, bonjour, Mathilde, ça va? You’re looking well.’

‘Merci, madame.’

‘Come in, Clarissa, she’ll take care of it. It’s lovely in the garden at 43this hour – the last roses are still blooming. But perhaps you’d like to freshen up first?’

‘I’m fine, thanks.’

‘Are you? Really?’

‘I think I will be. Though you’re right – when you reached me in Paris, I was at something of a low point. I was actually thinking about going back and facing the music. But you convinced me that old and grey though I am, it may not yet be time to fade away. So I came.’

‘And I am so pleased. I hope the train was not too distressing?’

‘It was perfectly comfortable. I’m glad you suggested the Train Bleu – not only convenient, but filled with the most entertaining people.’

‘Americans, yes? Quite mad, all of them, but they can be charming. Here, take this chair, the view will soothe your spirits.’

‘My spirits are already much soothed by being here.’

‘How long have we been anticipating this day?’

‘Do you know, I think we talked about living in Monaco the very first winter I knew you. Forty-nine years ago.’

‘Forty-nine? Impossible! I refuse to believe it was longer ago than last summer.’

‘Says the white-haired lady.’

‘And you, Clarissa – you had your hair cut off!’

‘I’m not used to it yet, I keep reaching up to adjust my pins. I haven’t had short hair since I was a child.’

‘It’s terribly chic. That’s from Paris, too?’

‘I had to convince the coiffeur that I wanted the same cut as the young woman beside me. He tried to talk me into a marcel wave, and couldn’t believe I wanted it bobbed.’

‘It’s just as well you didn’t ask for an Eton crop, he’d have fainted dead away.’44

‘No doubt. As it was, he charged me a ridiculous amount. In fact, I went through a great deal of money in Paris, altogether.’

‘New hair, new frock – a totally new you.’

‘I even replaced all my undergarments.’

‘A solid investment. There’s nothing like new lingerie to boost a woman’s self-esteem. And you’re here now, so your room, my kitchen, Mathilde’s car – my clothes, even, should any of them fit you – are yours for as long as you like.’

‘Thank you, dear, but I mustn’t abuse your hospitality. I’d like to set up on my own, as soon as possible.’

‘I’ve been asking around, as you suggested on the telephone – though what you said was very mysterious.’

‘One doesn’t like to go into detail with the exchange listening in.’

‘I know – it’s so bad here in little Monaco, no sooner do you hang up the earpiece than the doorbell rings with someone who’s heard the news.’

‘I figured that would be the case. And I’ll go into details later, when you and I are quite alone.’

‘We’re alone here. There’s only Mathilde, and she’s well accustomed to secrets.’

‘There’s no hurry, merely something I wanted you to think about, in case you have a friend who knows something about money. Not a banker, necessarily, but someone who—’

‘Ah, tea! Mathilde, I see you managed to get some of those adorable little macarons from Madame Renault – clever girl.’

‘My, look at that spectacular tea tray. Mathilde, you are an artist. How did you guess that I haven’t had a decent cup of English tea since I left Sussex eight days ago?’

‘Thank you, Mathilde, we’ll pour, you go on and hang up Clarissa’s things before they are crushed beyond salvation. Clarissa, dear, is anything locked? Do you want to give her the keys?’45

‘Oh, there’s just the one little valise that’s locked, never mind that, it’s mostly papers and a book. Nothing that needs hanging. Thank you, Mathilde.’

‘Here, I’ll be mother – I hope you don’t mind India tea. What were we talking about? Oh yes, bankers. I may have just the man.’

‘Another time. Let me just enjoy sitting still and being with you.’

‘Indeed, plenty of time to talk business when you’ve had a rest. But you’re not needing to arrange a loan, are you? You did say you had a little money, yes?’

‘I have plenty to get me started, thanks. Just not enough to keep me going – not in Monaco.’

‘It is an expensive sort of place.’

‘There’s a rather intriguing possibility that I want to talk to you about – or I suppose, four of them. But that’s terribly complicated and we both need to have our wits about us when I explain.’