9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

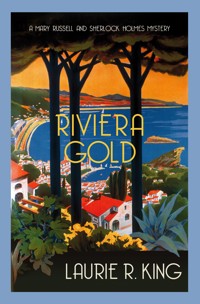

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Mary Russell & Sherlock Holmes

- Sprache: Englisch

Only hours after Holmes and Russell return from solving one riddle on the moor, another knocks on their front door.literally. It's a mystery that begins during the Great War, when Gabriel Hughenfort died amidst scandalous rumors that have haunted the family ever since. But it's not until Holmes and Russell arrive at Justice Hall, a home of unearthly perfection set in a garden modeled on Paradise, that they fully understand the irony echoed in the family motto, Justicia fortitudo mea est: "Righteousness is my strength."

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 652

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR LAURIER. KING

‘The Mary Russell series is the most sustained feat of imagination in mystery fiction today, and this is the best instalment yet’ Lee Child

‘These … are bestselling books because Laurie R. King captures the voice and character of Holmes as well as any of the thousand and more pastiches that have been written in imitation of Conan Doyle. But this is more than a mere copy. The narrative … is completely absorbing and motivates the reader to want to read the rest of the series’Historical Novels Review

‘Excellent … is completely absorbing and motivates the reader to want King never forgets the true spirit of Conan Doyle’Chicago Tribune

‘Outstanding examples of the Sherlock Holmes pastiche … the depiction of Holmes and the addition of his partner, Mary, is superbly done’Mystery Women

‘All [Laurie R. King books] without exception, leave me with a feeling of immense satisfaction at the quality of the story and the writing’It’s a Crime Blog

JUSTICE HALL

LAURIE R. KING

For my family

(YOU KNOW WHO YOU ARE)

Familia fortitudo mea est

Contents

EDITOR’S PREFACE

THIS VOLUME IS THE sixth chapter in the chronicles of Mary Russell and her partner, the near mythic (even, it would seem, in the 1920s) Sherlock Holmes. It comes chronologically after their 1923 adventure described in The Moor, but is linked with the characters from O Jerusalem, which took place in 1919.

I, Miss Russell’s literary agent and editor, had a certain amount of assistance in the preparation of this book, people who assisted in the task of ensuring that Miss Russell’s narrative did not stray too far from the path of historical truth. Ms Anabel Scott helped this poor Colonial to sort out the rules, regs, and terminology regarding the British aristocracy. Ms Tara Lengsfelder uncovered the paper written by Miss Russell on the boat to New York, running it to earth in an obscure American university journal from the spring of 1924. Mr Stuart Bennett, antiquarian bookseller extraordinaire, confirmed the titles of the books in the Justice Hall library.

Thanks to them all, and to nameless others, not the least of whom was the kind and anonymous soul who sent me Miss Russell’s manuscripts in the first place, for the benefit, and the puzzlement, of all.

LAURIE R. KING

Let justice roll down like the waters, and righteousness like an everflowing stream. – Amos 5:24

CHAPTER ONE

HOME, MY SOUL SIGHED. I stood on the worn flagstones and breathed in the many and varied fragrances of the old flint-walled cottage: Fresh beeswax and lavender told me that Mrs Hudson had indulged in an orgy of housecleaning in the freedom of our prolonged absence; the smoke from the wood fire seemed cleaner than the heavy peat-tinged air I’d been inhaling in recent weeks; the month-old pipe tobacco was a ghost of its usual self; and beneath it all the faint, dangerous, seductive tang of chemicals from the laboratory overhead.

And scones.

Holmes grumbled his way past, jostling me from my reverie. I stepped back out into the crisp, sea-scented afternoon to thank my farm manager, Patrick, for meeting us at the station, but he was already away down the drive, so I closed the heavy door, slid its two-hundred-year-old bolt, and leant my back against the wood with all the mingled relief and determination of a feudal lord shutting out an unruly mob.

Domus, my mind offered. Familia, my heart replied. Home.

‘Mrs Hudson!’ Holmes shouted from the main room. ‘We’re home.’ His unnecessary declaration (she knew we were coming; else why the fresh baking?) was accompanied by the characteristic thumps and cracks of possessions being shed onto any convenient surface, freshly polished or not. At the sound of her voice answering from the kitchen, I had to smile. How many times had I returned here, to that ritual exchange? Dozens: following an absence of two days in London when the only things shed were furled umbrella and silk hat, or after three months in Europe when two burly men had helped to haul inside our equipage, consisting of a trunk filled with mud-caked climbing equipment, three crates of costumes, many arcane and ancient volumes of worldly wisdom, and two-thirds of a motorcycle.

The only time I had come to this house with less than joy was the day when Holmes and my nineteen-year-old self had been acting out a play of alienation, and I could see in his haggard features the toll it was taking on him. Other than that time, to enter the house was to feel the touch of comforting hands. Home.

I caught up my discarded rucksack and followed Holmes through to the fire; to tea, and buttered scones, and welcome.

Hot tea and scalding baths, conversations with Mrs Hudson, and the accumulated post carried us to dinner: urgent enquiries from my solicitor regarding a property sale in California; a cheerful letter from Holmes’ old comrade-at-arms, Dr Watson, currently on holiday in Egypt; a demand from Scotland Yard for pieces of evidence in regard to a case over the summer. Over the dinner table, however, the momentum of normality came to its peak over Mrs Hudson’s fiery curry, faltered with the apple tart, and then receded, leaving us washed up in our chairs before the fire, listening to the silence.

I sighed to myself. Each time I managed to forget this phase – or not forget, exactly, just to hope the interim would be longer, the transition less of a jolt. Instead, the drear aftermath of a case came down with all the gentleness of a collapsing wall.

One would think that, following several taut, urgent weeks of considerable physical discomfort on Dartmoor, a person would sink into the undemanding Downland quiet with a bone-deep pleasure, wrapping indolence around her like a fur coat, welcoming a period of blank inertia, the gears of the mind allowed to move slowly, if at all. One would think.

Instead of which, every time we had come away from a case there had followed a period of bleak, hungry restlessness, characterised by shortness of temper, an inability to settle to a task, and the need for distraction – for which long, difficult walks or hard physical labour, experience taught me, were the only relief. And now, following not one but two back-to-back cases, with the client of the summer’s case long dead and that of the autumn now taken to his Dartmoor deathbed, this looked to be a grim time indeed. To this point, the worst such dark mood that I had experienced was that same joyless period just under five years before, when I was nineteen and we had returned from two months of glorious, exhilarating freedom wandering Palestine under the unwilling tutelage of a pair of infuriating Arabs, Ali and Mahmoud Hazr, only to return to an English winter, a foe after our skins, and a necessary pretence of emotional divorcement from Holmes. I am no potential suicide, but I will say that acting one at the time would not have proved difficult.

Hard work, as I say, helped; intense experiences helped, too: scalding baths, swims through an icy sea, spicy food (such as the curry Mrs Hudson had given us: How well she knew Holmes!), bright colours. My skin still tingled from the hot water, and I had donned a robe of brilliant crimson, but the coffee in my cup was suddenly insipid. I jumped up and went into the kitchen, coming back ten minutes later with two cups of steaming hot sludge that had caused Mrs Hudson to look askance, although she had said nothing. I put one cup beside Holmes’ brandy glass and settled down on a cushion in front of the fire with the other, wrapping both hands around it and breathing in the powerful fragrance.

‘What do you call this?’ Holmes asked sharply.

‘A weak imitation of Arab coffee,’ I told him. ‘Although I think Mahmoud used cardamom, and the closest Mrs Hudson had was cinnamon.’

He raised a thoughtful eyebrow at me, peered dubiously into the murky depths of the cup, and sipped tentatively. It was not the real thing, but it was strong and vivid on the palate, and for a moment the good English oak beams over our heads were replaced by the ghost of a goat’s hair tent, and the murmur of the flames seemed to hold the ebb and flow of a foreign tongue. New flavours, new dangers, and the sun of an ancient land, the land of my people; trials and a time of great personal discovery; our Bedu companions, Mahmoud the rock and Ali the flame. Odd, I thought, how the taciturn older brother had possessed such a subtle hand at the cook-fire, and had made such an art of the coffee ritual.

No, the dark substance in our cups was by no means the real thing, but both of us drank to the dregs, while images from the weeks in Palestine flickered through the edges of my mind: dawn over the Holy City and midnight in its labyrinthine bazaar; the ancient stones of the Western Wall and the great cavern quarry undermining the city’s northern quarter; Ali polishing the dust from his scarlet Egyptian boots; Mahmoud’s odd, slow smile of approval; Holmes’ bloody back when we rescued him from his tormentor; General Allenby and the well-suited Bentwiches and the fair head of T. E. Lawrence, and – and then Holmes rattled his newspaper and the images vanished. I fluffed my fingers through my drying hair and picked up my book. Silence reigned, but for the crackle of logs and the turn of pages. After a few minutes, I chuckled involuntarily. Holmes looked up, startled.

‘What on earth are you reading?’ he demanded.

‘It’s not the book, Holmes, it’s the situation. All you need is an aged retriever lying across your slippers, we’d be a portrait of family life. The artist could call it After a Long Day; he’d sell hundreds of copies.’

‘We’ve had a fair number of long days,’ he noted, although without complaint. ‘And I was just reflecting how very pleasant it was, to be without demands. For a short time,’ he added, as aware as I that the respite would be brief between easy fatigue and the onset of bleak boredom. I smiled at him.

‘It is nice, Holmes, I agree.’

‘I find myself particularly enjoying the delusory and fleeting impression that my wife spends any time at all seated at the feet of her husband. One might almost be led to think of the word “subservient”,’ he added, ‘seeing your position at the moment.’

‘Don’t push it, Holmes,’ I growled. ‘In a few more minutes my hair will be—’

My words and the moment were chopped short by the crash of a fist against the front door. The entire house seemed to shudder convulsively in reaction, and then Holmes sighed, called to Mrs Hudson that he would answer it, and leant over to deposit his newspaper on the table. However, I was already on my feet; it is one thing to relax in the presence of one’s husband and his long-time housekeeper, but quite another to have one’s neighbour or farm manager walk in and find one in dishabille upon the floor.

‘I’ll see who it is, Holmes,’ I said. He rose, maintaining the pipe in his hand as a clear message to our intruder that he had no intention of interrupting his evening’s rest, and tightening the belt of his smoking jacket with a gesture of securing defences, but he stayed where he was while I went to repel boarders at our door.

The intruder was neither a neighbour nor a lost and benighted Downs rambler, nor even Patrick come for assistance with an escaped cow or a chimney fire. It was a stranger dressed for Town, a thick-set, clean-shaven, unevenly swarthy figure in an ill-fitting and out-of-date city suit that exuded the odour of mothballs, wearing a stiff collar such as even Holmes no longer used and a brilliant emerald green necktie that had been sampled by moths. The hat on his head was an equally ancient bowler, and his right hand was in the process of extending itself to me – not to shake, but open-handed, as a plea. A thin scar travelled up the side of the man’s brown wrist to disappear under the frayed cuff of the shirt, a thin scar that caught at my gaze in a curious fashion.

‘You must help me,’ the stranger said. For some peculiar reason, my ears added a slight lisp to his pronunciation, which was not actually there.

‘I beg your pardon, sir,’ I began to say, and then my eyes went back to the darkness on his temple that in the shadowy doorway I had taken for hair oil. ‘You are hurt!’ I exclaimed, then turned to shout over my shoulder, ‘Holmes!’

‘You must come with me,’ the man demanded, his command as urgent as his fist on the wood had been. Then to my confusion he added a name I had not heard in nearly five years. ‘Amir,’ he murmured, and his shoulder drifted sideways, to prop itself against the door-frame.

I stared at him, moving to one side so the interior light might fall more brightly on his features. I knew that face: Beardless as it was, its missing front teeth restored, the hair at its sides conventionally trimmed, and framed by an incongruous suit and an impossible hat, it was nonetheless the face of a man with whom I had travelled in close proximity and uneasy intimacy for a number of weeks. I had worked with him; shed blood with him. I was, in fact, responsible for that narrow scar on his wrist.

‘Ali?’ I said in disbelief. ‘Ali Hazr?’ His mouth came open as if to speak, but instead he stumbled, as if the door frame had abruptly given way; his right hand fluttered up towards his belt, but before his fingers could reach his waistcoat, his eyes rolled back in his head, his knees turned to water, and fourteen and a half stone of utterly limp intruder collapsed forward into my arms.

CHAPTER TWO

THE MAN LYING BETWEEN the crisp white sheets of the guest bed was very like Ali Hazr, but also distinctly unlike the Arab ruffian Holmes and I had known. In fact, I had nearly convinced myself that our visitor was merely a stranger with a strong resemblance to the man – a brother, perhaps – when a jab from the doctor’s sewing needle brought him near to consciousness, and he growled a string of florid Arabic curses.

It was Ali, all right.

Before Holmes’ pet medical man had clipped the thread from his half-dozen stitches, the patient had lapsed back into the restless swoon that had gripped him from the moment he fell through our door. Seeing his tossing head and hearing the apparent gibberish from his lips, the doctor reached back into his satchel for a hypodermic needle. With that, Ali finally succumbed to oblivion.

I adjusted the pad of clean towelling underneath his bandaged scalp and followed the two men out of the room, leaving the door ajar.

Downstairs in the kitchen, Dr Amberley was scrubbing the blood from his hands and giving Holmes a set of unnecessary instructions.

‘I’d say his concussion is a mild one, but you’d best keep an eye on him, and if his pupils become uneven, or if he seems over-lethargic, telephone to me immediately. The dose of morphia I gave him was small, because of the concussion – it ought to wear off in three or four hours, although he may well sleep longer than that. I suppose you wish me to say nothing about this visitor of yours?’

‘I think not. At this point I have no idea why he’s here or what happened to him, and I’d not want to invite an attacker to join us. Although by the appearance of his overcoat, I should say this happened far from here.’

It was true. Ali’s incongruous city suit had been stiff with dried blood, his shirt collar saturated to the shoulders. Whatever had brought him here, desperation might well follow on his heels.

When the doctor had gone and Mrs Hudson was tut-tutting over the ruined clothing, Holmes picked up his hastily abandoned pipe, knocked it out, and began to tamp fresh tobacco into the bowl. I went through the house to secure the doors and windows and draw the curtains, just in case.

‘It has to be something to do with Mahmoud,’ I said when I came back. ‘Ali would not have come to England without him, and would not have come to us for help except if Mahmoud were in grave danger.’

‘It is difficult to imagine the one Hazr without the other,’ Holmes agreed. He got the pipe going, then resumed his three-week-old newspaper.

‘But, shouldn’t we do something? He may sleep for hours.’

‘What do you propose?’

‘We could telephone to Mycroft.’

He did lower the paper a fraction to consider the proposition, then shook his head.

‘My brother is in London, unless he’s left since this morning. If Ali wanted Mycroft, he’d have stopped there. He wanted us, which meant that either he thought we would not respond to a mere telegraph or telephone message, or secrecy was foremost. No, Ali came from Berkshire to see us, not to speak with Mycroft. We shall have to be patient.’

The unused portion of a return ticket in Ali’s pocket had revealed a journey from the farthest reaches of Berkshire, a rural station I’d never heard of called Arley Holt. It seemed likely that he had been injured during his journey’s break in London. It was also more than possible that the wound had been not accident, but active threat; something, after all, had prevented him from seeking medical attention when he disembarked in Eastbourne, miles from our door.

Ignorance is always frustrating, never more so than when accompanied by the feeling that it obscures the need for action. Holmes and I wore our patience like a pair of horsehair shirts, prickly and ill-fitting, and while we kept our eyes on the printed word, our ears were turned towards the stairs, eager for the slightest sleep-befuddled query.

It did not come. Mrs Hudson abandoned her scrubbing brush and retired to her quarters. The fire burnt low. Midnight approached, with no movement from the guest room.

Finally, Holmes rattled his paper shut with an air of finality and fixed me with a gaze. ‘And the cares that infest the day,’ he pronounced, ‘shall fold their tents like the Arabs, and as silently sleep away.’

We took ourselves to bed, but not to silent sleep; nor was the air filled with the music from the first part of his misquotation.

I had forgotten how emphatically Ali snored.

Two of us in the house slept little.

Morning came, the aroma of coffee trickled its way up the stairs, and still the Hazr snores rattled the windows. Not until after eight o’clock did they abruptly cease. Holmes and I looked at each other. Mrs Hudson came in from the kitchen, drying her hands on her apron and cocking her head at the ceiling.

‘Shall I make another breakfast, then?’ she asked.

‘Either that or send for the undertaker,’ I answered, but then a rattle of movement came from the bedstead over our heads, followed by the thump of feet hitting the floorboards. They stopped there, either through dizziness or because Ali noticed that he was more or less naked. Holmes folded his newspaper (he’d worked his way up to the previous week) and rose.

‘If you would like to make a pot of tea, Mrs Hudson, Russell will bring it up. I’ll find our guest a dressing gown. Give him a minute, Russell, to get his bearings.’

I was not certain whether Holmes was referring to the inevitable confusion following a head injury, or to the specific discomfort this man might feel after having tumbled into the arms of a woman he’d spent the better part of six weeks insulting, ignoring, and mistrusting. Our relationship had become considerably more jovial after I had come close to killing him a couple of times (accidents both, I hasten to say), but I might still not be the person Ali Hazr would have chosen to pick him up following a moment of vulnerability.

To be fair, I had to permit him to resume his mask of omnicompetence. Whatever had driven him to the extremity of seeking aid, it would only further complicate matters to begin with inequality. So I allowed Holmes to trot off upstairs without me. I did not even snatch the tray from Mrs Hudson’s hands, but meekly waited for her to rearrange the biscuits into an aesthetic design before I took up the refreshment and carried it upstairs.

Holmes had built up the fire in the guest room and was seated on the low bench at the foot of the bed. The room’s armchair held Ali, clad in a warm dressing gown and a pair of Holmes’ pyjama trousers that extended past his toes. He looked up at my entrance and watched me set the tray down on the small table by his side. I poured him a cup. He added milk (rather to my surprise, as Arab tea is taken black) and two sugars, then drank thirstily. I refilled his cup and pulled the footstool up to the other side of the fireplace. A quick glance at the pillow confirmed that he’d bled, but not profusely, and none of the stains looked fresh.

The second cup followed the first down his throat, and he set it onto the saucer with the barest tap. Ali glanced at me briefly, and away.

‘The English beverage,’ he commented, which might have sounded like disparagement had he not drunk it so greedily. I decided this was his version of thank you. His hand went to his scalp, exploring the surface of the bandage. ‘Someone has put in stitches.’

‘Six,’ Holmes told him. ‘One of our neighbours is a retired surgeon. And in case you are concerned, he knows well how to keep a confidence.’

‘Good. I … apologise for my state yesterday night. I do not remember too clearly, but I have the impression that my arrival was somewhat more … dramatic than I had intended.’

The drama of his arrival the previous evening, however, had been nowhere near as startling as the words he had just pronounced. And not only the words themselves (Ali Hazr, apologising?) but their delivery.

My first clear impression of Ali all those years before, seen by the light of a tiny oil lamp in a mud-brick hut near Jaffa, had been: Arab cut-throat. Glaring eyes and garish embroidery, knife as well as revolver decorating his belt, his very moustaches looking ferocious – from his flowered headdress to his red leather boots, Ali Hazr had been in that first moment what he remained the entire time: a Bedouin male, proud member of a haughty race, fiercely indisposed to tolerate anyone but Mahmoud, his brother in the deepest sense of the word. Touchy and arrogant, his hand reaching for his knife at the slightest provocation, in his attitude towards us Ali had veered between mortal threat and withering contempt. Passing the tests he and Mahmoud had set us, becoming a companion worthy of their trust, had been a profound source of pride that I had never acknowledged, even to Holmes. I had, in truth, been a different person when Ali and Mahmoud Hazr finished with me.

I looked at the man in the chair, and other than the colours of the tie draped over the bedstead, I could perceive little of that vivid personality now. His erect spine, and perhaps the darkness in his eyes, but the flash was missing from their depths, the aura of simmering violence well and truly damped down. With the gap in his front teeth bridged, even his oddly ominous lisp was gone, his once-heavy accent no more than a faint thickening of gutturals and a subtly non-English placement of the words on the tongue. Had Holmes not trained my ear, I might have thought our intruder merely an ordinary, tame English gentleman. Ali Hazr had shaved away far more than facial hair in transforming himself into this.

As I studied him, those black eyes glanced up at me again, and in that brief moment of contact I felt a spark in them, and read in his half-familiar mouth a distinct grimace. He knew what I was seeing – or rather, not seeing – and it was a face he was not happy about showing. His current appearance was no mere disguise.

‘I think I should introduce myself,’ he said. I had the impression he spoke through gritted teeth. ‘My name is Alistair Hughenfort. Alistair Gordon St John Hughenfort. Although even as a child, my family called me Ali.’

Holmes’ head jerked up and I, frankly, stared. Hughenfort? He must be joking. The Hughenfort name was a thing to conjure with, a noble name in the fullest sense of the word, one of a thin handful of the nation’s families that had actually stepped onto England’s shores at the side of William the Conqueror. Half the European wars had a Hughenfort leading some vital charge – and half the rebellions had a younger Hughenfort somewhere in there as well. But as an assumed name, it would have been like disguising himself as the Prince of Wales. It could only be the truth. Holmes shook off the historical details and went for the main issue.

‘And Mahmoud?’

Our guest sat up sharply, scarcely wincing as the urgency of his mission overrode his ailments. ‘He needs us. I need your help.’

This extraordinary confession passed straight over Holmes’ head. ‘I understood that to be so. My question was, what is Mahmoud’s name?’

The wounded ex-Arab braced himself, took a soft breath, then answered in an even voice. ‘The man you know as Mahmoud Hazr was born William Maurice Hughenfort.’ He waited, his eyes on Holmes, to see what we would make of the statement.

It meant nothing to me, but Holmes’ eyes assumed the faraway look that indicated a rapid search through his prodigiously stocked mental box rooms. ‘Maurice Hughenfort. Known as Lord Marsh. Younger son of the Duke of Beauville. Good Lord. I should have suspected that family immediately when I saw where your ticket was issued last night.’

‘I’m sorry?’ I asked. Was this something from his accumulation of newspapers, a recent event we had missed while slogging through the depths of Dartmoor?

But Holmes waved a dismissive hand in the direction of the laboratory. ‘Ancient history, Russell. He’ll be in Debrett’s. Unless …?’ He turned an eye to the man in the chair.

‘The entry is still there,’ Ali – Alistair? – confirmed. ‘Incomplete, but there.’

Curious, I went down to Holmes’ laboratory and took his Debrett’s from its resting place on a shelf between an assortment of labelled coal samples and a massive and outdated treatise on Bertillonism. I went back down the corridor, flipping over the pages until I came to the name Beauville. It began with a crest of typically unlikely looking creatures and a snarl of heraldic devices above a motto of equally unlikely Latin, Justitia fortitudo mea est.

The Duke of Beauville, the list began, with the name of the (then-present) Duke, Henry Thomas Michael. I skimmed over the long paragraph of fine print that followed, packed with descending titles, education, and honours: Earl of Calminster, Earl of Darlescote, baron of this and baron of the other, mayor of, secretary of, steward of, so on and so forth.

I turned the page to find the Family of Hughenfort entry, where the dates began in the eleventh century, although details of the early barons were both few and heavily mythologised. Words jumped out: knighted; liberal to his tenants and servants; high sheriff; chief justice; spirited debates in Parliament; battle of various places and service to king so and so and distinguished statesman. Baron gave way to earl and eventually, in the early eighteenth century, to duke.

Finally I saw the name Maurice, and I slowed to read the entry of his father’s generation:

Gerald Richard Adam, 5th Duke of Beauville, b. 14 May 1830, then the details of two marriages, with ‘issue’ given as:

1. Henry Thomas Michael, Earl of Calminster, b. 1859, m. 1888 to his cousin Sarah, dau. Rev William Malverson, has issue: Gabriel Adrian Thomas b. 1899.

2. William Maurice, b. 1876 (whereabouts unknown since 1900)

3. Lionel Gerald b. 1882

1. Phillida Anne b. 1893

I had to travel back up the lists to find Ali, but there he was, under a cousin of the fourth Duke’s: Alistair Gordon St John, b. 1881, Eton, Trinity. Badger Old Place, Arley Holt, Berks. And again that odd notice, whereabouts unknown, although in his case it was since 1902.

The two Hughenfort cousins had slipped beneath the ken of Debrett’s all-knowing eyes, into the king’s service in the Middle East. Quite an accomplishment for a pair of Hons. So why had they come back?

Further queries were interrupted by Mrs Hudson and another tray, and although the man I was trying to think of as Alistair was reluctant to break off his quest even to take on nourishment, Mrs Hudson stood over him until she was satisfied that he was not about to let the buttery eggs go untended. Holmes, seeing that our guest’s mouth was unavoidably occupied, stepped into the gap.

‘Before your time, Russell. There was a mild sensation in the newspapers concerning a vanished baronet. Somehow a rumour got around that he had boarded a ship for New York and never arrived. 1896 or ’97, as I recall.’

‘Seven,’ mumbled Alistair around his toast.

‘The family denied the rumours, claimed their second son was merely travelling in Russia, but when Debrett’s came out the following year it gave his address as “unknown”, and Burke’s followed. But – correct me if I am wrong – the son came home a few years later. For his father’s funeral?’ The bandage nodded. ‘When he disappeared again after that, no one could work up much interest.’

Ali washed the toast down with the last of his tea; he had eaten all the eggs and the tomato, but left the bacon and sausage untouched. ‘When I joined him in Palestine in 1902, my own family had learnt their lesson, and gave it out that we had mounted an expedition into the Himalayas and were not expected to return for years. I had my club forward letters, first to my home, and then later, when we became … associated with your brother Mycroft’s organisation, to his office. It disarmed suspicion.’

The idea of Ali Hazr, Arab cut-throat and clandestine agent for His Majesty’s government, as a clubman with noble blood in his veins made for an interesting picture. Holmes, however, returned to the question that had brooded over the house since the previous night.

‘In what trouble is Mahmoud?’

Our guest looked down at his hands with a faint smile. ‘It is good to hear my brother’s name spoken. It gives me hope.’ For one startling instant, Ali Hazr passed through the room, his hand creeping to the hilt of his wicked knife, ebony eyes flaring, the rhythm of a foreign tongue riding the English words. And then the ghost of a dramatic moustache faded, the swarthy skin became merely that of an outdoorsman, and we were looking again at Alistair Hughenfort.

‘Four months ago, we received news that his brother was dying. Henry. His older brother. The funeral was in September.’

A picture began to take form out of the fog of ignorance.

‘His older brother, the duke,’ Holmes said. Ali nodded; Holmes settled his back against the end of the bench and allowed his eyelids to droop shut, the better to listen. He suggested to Ali, ‘And the duke had no son.’

However, Ali shook his head. ‘Henry – the sixth Duke – did have a son. Gabriel. The boy enlisted on the day of his eighteenth birthday, in August 1917. He was killed fifty-one weeks later. Gabriel was engaged, but not married. Henry had no other children.’

‘Were there no other brothers?’

‘Lionel, six years younger than Mah – than Marsh, but he died before the War. And there is a sister, Phillida, from the old duke’s second wife. She is seventeen years younger than Marsh.’

Somehow, it was difficult to conceive of Mahmoud Hazr as one of a family of siblings going through the common lot of birth, teething pains, skinned knees, and all the other stages of human growth. I began to get an inkling of how absolute his own reinvention had been – more profound even than that of his relative Alistair. It was then the full picture hit me: Mahmoud Hazr, itinerant scribe for the illiterate Palestinian countryside, eyes and ears for General Edmund Allenby, the inadequately washed Bedouin who scratched his ribs and cursed his mules and roasted his coffee over a dried-dung fire in the dark confines of a goat’s-hair tent, was also the seventh Duke of Beauville: his embroidered robes replaced by ermine, that dark, knife-scarred face topped not by khufiyyah, but by coronet.

It was a lot to absorb.

Holmes, as usual, kept to the essentials. ‘I fail to see what I might be expected to do in this situation. If Mahmoud – if your cousin – Maurice – confound it! If Maurice Hughenfort feels it necessary to assume the duties that accompany his title, there is little I, or Russell, can do to dissuade him. If he does not so choose, he could always let the dukedom be in abeyance for his lifetime. Surely there must be another heir in the woodwork. Did the other brother, Lionel, have no heir?’

‘There are … complications. You will understand when you see him. Will you come?’

I had known it would come down to this. With the mud from the last outing still damp on my boots, we were about to set out again. I must have sighed, because Ali pulled himself up, his face going dark in a way I remembered well.

‘I ask you this—’ he began, but Holmes put up one hand, saving a proud man from having to plead.

‘We will of course come with you,’ he said. Then he opened an eye, and added, in Arabic, a phrase translating roughly, ‘One man’s hunger makes his brother weak.’ At the word ‘brother’, our guest froze; then he nodded, once, both as thanks and as acknowledgment of our right to claim that relationship.

Even I: I had, after all, been to all appearances a boy during the weeks in Palestine. I, too, might claim brotherhood to the formidable Mahmoud.

‘You have neglected to tell us what happened to you on the way to Sussex,’ Holmes pointed out, settling back into the bench.

‘What happened – oh, you mean this.’ Ali’s hand went to the gauze on his head. ‘Stupidity. This country makes a man soft. I imagined I was safe, and walked straight into a situation. It would never have happened in Palestine.’

Holmes abruptly abandoned his languid pose. ‘You were attacked? Robbed?’

I fully understood the note of incredulity in Holmes’ voice: It was hard to imagine a man with the lightning-fast responses of Ali Hazr falling victim to a common thief.

‘No. Caught up in a riot.’

‘In London?’

‘A small riot. A Guy Fawkes celebration, I suppose – I had forgotten entirely about Guy Fawkes – that joined with a group of unemployed workers and got out of hand.’ He saw our unwillingness to accept that truncated account, and reluctantly explained. ‘When I got into Paddington I had an hour before the Sussex train, so I walked to Victoria instead of taking a taxi or the underground. Just before the station I came up to a knot of men with a pile of wood, as if they were about to light a bonfire on the street. They objected to the police clearing them off; bricks were thrown, truncheons raised. I thought the disturbance was behind me, then something struck me – truncheon or cobblestone, who knows? – and knocked me into the street in the path of a lorry. I managed to roll out of its way, and half fell into the nearest doorway. A pawnshop, as it turned out, where a handful of others took refuge as well. They wanted to take me to a doctor’s surgery, but I could not risk missing the train.’

Riots in London? Ever since the War had ended, and especially in recent months, the unrest of common workers had steadily increased: Men who had spent four years in the trenches were ill-equipped to put up with dole queues. I had not known that open battle had broken out.

‘It was nothing,’ he insisted. ‘Carelessness and a headache. We must go now.’

The man was in no condition to travel. Indeed, once on his feet he swayed dangerously, and would have fallen but for Holmes’ hand on his shoulder, both supporting and holding him back.

‘If we left now,’ Holmes told him, ‘we should merely find ourselves decorating an ill-heated waiting room for several hours. There is no service we can do for the Duke of Beauville that cannot be better done by going prepared.’

The room went abruptly cold as Ali Hazr drew himself up, no sign of weakness in him, his eyes dark with threat and his right hand fumbling at the sash of his borrowed gown as if to draw steel. ‘You will not call him by that name,’ he commanded. Neither of us breathed, and I fought down the urge to retreat at this sudden appearance of Fury in dressing gown and bandage.

‘I see,’ Holmes replied mildly, although I doubted that he did, any more than I. However, he decided to let pass for the moment what was clearly a basket of snakes, and said only, ‘Perhaps you might allow Russell and me to pack our bags and take care of a few matters of urgent business. You rest here. I will enquire if Mrs Hudson can assemble you some clothing.’

We left him then, and although I half expected to hear the crash of his collapse onto the carpet, he must have succeeded in making his way to the bed. Only when we reached the main room, where Holmes dived into the heap of letters to extract those most pressing of reply, was I struck by the full scope of the undertaking: I was headed for the country house of a peer, no matter how unlikely a peer. We were full into the season of social weekend shoots, and Saturday loomed near. In something not far from horror, I turned to my husband.

‘Holmes! Whatever shall I do? I haven’t a thing to wear.’

CHAPTER THREE

IT WAS NOT STRICTLY accurate, of course, that I had nothing to wear. True, most of the garments hanging in my wardrobe were not exactly the thing for a country house Saturday-to-Monday, but I could pull together a sufficient number of quality garments (if in somewhat out-of-date styles and hem lengths) to remain presentable. I doubted that Mahmoud, even as the Duke of Beauville, would gather to his bosom the frothy cream of society.

Ten years earlier, my cry might have been more serious: Before wartime shortages had changed both fashion and social mores, even a three-day country house visit would have required a dozen changes of clothing, and more if one intended to venture out for a day’s shooting or to sit a horse. With the relaxed standards of 1923, however, I thought I might be allowed to appear in the same skirt from breakfast until it was time to dress for dinner. Thus, two or three suitcases instead of that same number of trunks.

I piled a selection of clothing on my bed and, since I knew she would repack them anyway as soon as my back was turned, left Mrs Hudson to it. I found Holmes just closing up his single case, which I knew would contain everything from evening wear to heavy boots.

‘You don’t imagine dinner will be white tie, do you, Holmes?’

‘If the possibility presents itself, we can have Mrs Hudson send a gown and your mother’s emeralds.’

‘I cannot imagine Mahmoud in white tie. But then, I can’t imagine Mahmoud in anything but Arab skirts and khufiyyah.’

‘The revelations have been thought-provoking,’ he agreed, surveying the contents of his travelling-razor case and then slipping it into the bag’s outer pocket. ‘Although you may remember, I said at the time they were not native Arabs.’

‘True, but I believe you identified their diphthongs as originating in Clapham.’

He raised his eyes from the trio of books he had taken up, and cocked one eyebrow at me. ‘Surely you understood that to be a jest.’

‘Oh, surely.’

He discarded two of the volumes and pushed the survivor in after the razors. ‘By the way, Russell, our guest seemed anxious that we wipe those names from our tongues. Our Arab guides are now, I take it, Alistair and Maurice. Or possibly “Marsh”.’

‘Not Mr Hughenfort and the Duke of Beauville – or would it be Lord Maurice? Or, not Maurice, what was his first given name? William? What is the proper form of address for a duke who is refusing his title, anyway?’

‘I believe the matter will be simplified when we are presented as old acquaintances.’

‘Well, if he’s changed as much in appearance as Ali has, it won’t be difficult to call him by another name. You do realise, by the way, what his name means?’

‘A pleasant irony, is it not?’

Maurice, which one might translate as ‘The Dark-Skinned One,’ has its origins in the word ‘Moor’. Maurice: The Arab.

Patrick brought the motor to our door in time for the afternoon train. We loaded our cases in the boot and settled an ill-looking Alistair into the back, well swathed in furs and with two heated bricks at his feet. At the station, we had to help him up into the train carriage – his bruises had now stiffened, and the blood loss he had sustained made him quite vulnerable to the cold November air. We retained the heaviest travelling rug and wrapped him in it against the inadequate heat of the compartment; he was asleep before the train pulled out of Eastbourne.

I nestled down into my own fur-lined coat and, while I watched Alistair Hughenfort sleep, meditated on that peculiar human drive, loyalty.

On entering Palestine in the closing days of 1918, Holmes and I had been pushed into the vehemently unwilling arms of two apparently Arab agents for the British government intelligence service – that is, Holmes’ elder brother, Mycroft. We had begun on a note – an entire chorus – of mistrust, resentment, and dislike, and only slowly had those abrasive feelings softened beneath the continuous rub of shared tribulation and danger. When I had proved that I would, if pushed to the extremity, kill to protect our band of four, Ali’s eyes had finally held a degree of respect. When later we demonstrated our willingness to die for each other, we were forever bound, like it or not.

Five years or fifty, when people have sweated, suffered, and shed blood together, there can be no hesitation: If one calls, the other responds. We had shared salt and bread, those staples of Bedu life; now it appeared that we were about to share our combined strength. My blood family had been dead for nine years; however, in the interim I had acquired a most singular pair of brothers.

Darkness fell outside the windows long before we reached the tiny village of Arley Holt. We were the only passengers to disembark – as far as I could see, we had been the last passengers on the entire train.

Nonetheless, a figure trotted out from the warmth of the station to meet us, bowling along on legs too small for his stocky body and talking a streak from out of his bristling ginger whiskers, his gravelly voice comprising a delicious admixture of highland Scots, East End London, and Berkshire.

‘There you are, Master Alistair, I was just going to spread my car rug out on a bench and stop the night here, meet the first train in the morning. Had a good trip did you? – I see you found your friends – no, miss, I’ll carry those, the good Lord blessed me with strong shoulders and I’m happy to use them – watch your step here, should’ve brought a torch I should’ve, daft of me – oi, stop a mo’,’ he cautioned sharply, realising in the darkness that one of us was moving very slowly indeed. ‘What’ve you done to yourself, young master? You’re hurt!’

I expected Alistair to dismiss the servant’s concern with a curt phrase – as Ali, he certainly would have – but he surprised me. ‘It’s nothing, Algy. I got bashed in Town yesterday and I’ve gone all stiff on the train. I’ll be fine after a night’s sleep.’

‘Blimey,’ Algy muttered. ‘Let you out of me sight and you get yoursel’ bashed, what will the Missus say, I can’t think. Here now, you pack yourselves good and snug in the back, that’ll warm you.’ He wrestled from the boot an enormous bearskin rug that swallowed Alistair, with plenty left to cover the passengers on either side of him.

Holmes, without asking, went around to the front of the old motor and yanked the starter handle for the driver. When the engine had coughed and sputtered its way to life and Holmes was back inside (where ‘snug’ was indeed the word, as well as being redolent of large carnivores), the driver turned in his seat.

‘Much obliged, sir, I’d’ve had a time getting ’er going in the cold. Name’s Algernon, Edmund Algernon.’ Ali roused himself enough to give the driver our names; Algernon touched his cap in response, then turned to shift the motorcar into motion.

The village died away in less than a minute; the night closed in. The tunnel of our headlamps revealed a well-kept track with hedgerows high on either side, so close that if I’d dropped the window I could have touched them without stretching, although our vehicle was narrow. Algernon kept up a running commentary, directed at his employer but with the occasional aside of explanation to us, concerning a flock of sheep, a neighbour’s rick fire, another neighbour’s newborn son, the relief when a villager’s illness was deemed not after all to be the dreaded influenza, and half a dozen other topics, all of them rural and thus commonplace to me – although again, not the sort of thing I would have associated with the silent figure at my side.

After what seemed a long time, our headlamps illuminated a crossroads. Algernon prepared to go to the left. Alistair spoke up.

‘Justice Hall, if you would, Algy.’

‘Ah,’ said our driver, allowing the motor to drift to a halt. ‘Well, you see, sir, Lady Phillida arrived today.’

The normally effusive Algy let the flat statement stand with no further embroidery; indeed, from his master’s reaction, none was needed.

‘Damn. She wasn’t due until Thursday. All right, home then.’

‘Home’ lay to the left. After a few minutes the hedgerows fell away, replaced by a brief stretch of wire fence, then stone walls, and finally a gate – not a grand ceremonial entrance, just something to keep out livestock. This was followed by half a mile of freshly laid gravel with centuries-old trees on either side, then another stonewall, with farm buildings, a heavily mulched herbaceous border, and a passage tunnelled through the ground floor of a long stone building. When we emerged, the headlamps played across a clear expanse of tidy, weed-free gravel as Algy pulled up to a stone building with high windows of ancient shape and numerous small panes. We came to a halt facing a wooden porch that was buried beneath a tangle of nearly bare rose vine.

The door at the back of the porch opened almost as soon as the handbrake was set, and out hurried Algernon’s female twin. Her voice was high and lacked the influence of Scotland and London, but it was every bit as free-flowing as our driver’s. I prayed that this was ‘the Missus’ Algernon had mentioned – a married Ali would be the final straw.

‘Oh, Mr Alistair, you must be fair frozen, it’s come so bitter out; let’s have you in by the fire now – why, whatever’s happened?’

These two had all the earmarks of old family retainers, riding a comfortable line between familiarity and servitude. In fact, for a moment I played with the idea that Algy and the Missus might be two more of Mycroft’s peculiarly talented agents, placed here with Ali in a meticulously choreographed act – down to the very name Algernon, which meant ‘The Whiskered One’ – but no, I decided reluctantly; they were both too idiosyncratically perfect for artifice. The Missus bossed and fussed Ali (who cursed his infirmity beneath his breath, in Arabic and English) through the porch and into the low, oak-panelled entrance vestibule, while Algernon, reassuring us that he’d bring our suitcases from the motor, pushed us in after them and closed the heavy, time-blackened door at our backs.

With her hand under Alistair’s arm (no mean feat, considering the ten-inch disparity in their height), the housekeeper led him into the adjoining room. A wave of warmth billowed out through the draught-excluding leather curtain, through which we gladly followed.

And there I stopped dead.

Had I been asked to place this man Alistair Hughenfort into an English setting, I might, after considerable thought, have described one of two extremes: It would either be the stark, bare surroundings of a man long accustomed to living within the limits of what a couple of mules can carry, or else ornate to the point of glut, both as overcompensation for the desert’s forced austerity and as a means of evoking the richly coloured clothing, drapes, and carpets of the Arabic palette.

Instead, Ali Hazr was at home in the most perfect Elizabethan great hall I’d ever seen. Not a nobleman’s hall – not huge, nor ornate, nor built to impress, just a room which for three hundred years had sheltered its family and dependents from the outside world’s storm and strife.

The room was perhaps fifty feet long, half that in width and height. The walls were of beautifully fitted limestone blocks, aged to dark honey near the roof beams and above the fireplace, paler near the floor and in the corners. The beams arched black high overhead, all but invisible in the dim light, and the high, manypaned windows above our heads were black and uncurtained. Electric lamps shed an oasis of light before the crackling fire, illuminating the lower edges of the tapestries that covered the stonework, hangings so dim with the patina of generations, they might well have disintegrated with cleaning.

On the hall’s end wall, opposite the wooden gallery under which I stood amazed, hung what after a moment’s study I decided was the head of a boar, bristling furiously over the room. The huge and weirdly distorted shadow it cast up the wall made the head look like some enormous prehistoric creature brought forward in time. Perhaps it actually was as large as it appeared: The tusks, their ivory darkened along with the stones, looked longer than my outstretched hand.

‘Shall I take your coat, ma’am?’ enquired a voice at my elbow. The Missus had settled Ali to her satisfaction, stripping him down to Holmes’ borrowed suit and propping his feet onto a cushioned rest, and she was now turning to his guests. Obediently, I took off my heavy coat and draped it over the one Holmes had lent Ali. The cold bit my shoulders, so I hastened down the room to join the men in front of the fire. Once there, I rather wished I’d kept my coat; warming one’s self before a head-high fireplace in a large room involves one roasted side and one chilled, and the impulse to revolve slowly in compensation.

‘Mrs Algernon,’ Alistair called. ‘Our guests might like a drink to keep out the cold.’

Mrs Algernon, having deposited our outer garments out of sight, had come back into the hall with her attention fixed on the bandage around her charge’s head. His request was intended, I thought, to deflect her interest more than to provide us refreshment; if so, it had the desired effect. After a brief hesitation, she turned and left the room again. Alistair – I could almost think of him by that name, given the setting – closed his eyes for a moment, then removed his feet from the settee.

‘Mrs Algernon will give us dinner shortly. Not as artful a meal as you would have got at Justice Hall, I grant you, but then again, the company won’t sour your digestion.’

Holmes sat down on one end of the sofa and took out his tobacco pouch. ‘You do not wish to encounter Lady Phillida?’

‘Marsh’s sister is not the problem, or not entirely. It’s Phillida’s husband, Sidney – known as ‘Spinach’ and just as likely to set your teeth on edge. They’ve been in Berlin, and weren’t due to return until the end of the week. Having them back … makes matters more difficult. No matter,’ he added, and gave a dismissive wave of the hand.

With that small gesture, Ali and Alistair came together before me for the first time. Had he been speaking Arabic, that final phrase would have been ma’alesh, the all-purpose verbal shrug that acknowledges how little control any of us have over our fates. Ma’alesh; no matter; never mind; what can one do but accept things as they are? Ma’alesh, your pot overturned in the fire; ma’alesh, your prize mare died; ma’alesh, you lost all your possessions and half your family. The word was the everyday essence of Islam – which itself, after all, means ‘submission’.

Clean-shaven and bare-headed, his former long, bead-flecked plaits with khufiyyah and agahl transformed into a head of cropped and thinning English hair, Ali’s ornate embroidered robes and high, crimson boots replaced by Holmes’ old suit and well-worn brogues, the ivory-handled knife and mother-of-pearl-handled Colt revolver he had invariably worn now seeming as unlikely as a feather boa on a rhinoceros, and carrying with him an odour not of cheap scent but of mothballs and damp wool – nonetheless, that powerful and exotic figure was still there, a ghostly presence beneath the ordinary English skin. Ma’alesh.

Mrs Algernon broke my reverie, bustling in with a tray laden with her idea of warming drinks. The fumes of the hot whisky reached us before she did, and although the tray also held the makings for tea, there were three full mugs of her steaming mixture. She set one mug down within arm’s reach of each of us; as soon as she had left the hall, Alistair put his back on the tray and poured himself a cup of tea. One thing that had not changed: Although the Bedu were not the most outwardly observant of Moslems, they did generally demur at pork and alcohol, and although I had once seen Ali eat bacon, I’d never seen either Ali or Mahmoud take strong drink. Alistair’s diet, it seemed, remained as it had been.

The hot whisky did the trick for two of us (although I couldn’t have sworn that the fumes did not affect the abstainer). Mrs Algernon came in before the cups were empty to say that dinner was ready when we wished, and although Holmes and I were impatient to hear more of the teeth-on-edge Sidney, Alistair obediently put down his teacup and forced himself to his feet, raising his weight more by willpower than by the strength of his muscles. His first steps were supported by the chair back, and Holmes and I exchanged a glance. The man was in no shape to be questioned.

The dining room, fortunately, was low of ceiling and therefore made positively cosy by its fire. It smelt heavenly – a heaven made not of subtle foreign spices and delicate sauces, but of earthy comfort and, oddly, childhood pleasures. I sat down to my plate and allowed Mrs Algernon to ladle out my soup. At the first spoonful, Alistair’s description of the cuisine was justified: Plain-looking, it tasted of root vegetables and peasant grains, herbs rather than spices, chicken rather than the beef tea it resembled.

Under the warmth of the room (and the fumes of the drink, perhaps) our host’s social instincts were aroused, and when the housekeeper had left, he came out with an unexpectedly chatty explanation of the substance in our bowls. ‘This is Mrs Algernon’s patented cure-all. For all the years I’ve known her, she’s kept a pot on the back of the cook stove and tosses in whatever she has at hand. It never goes cold, never goes empty. Somewhere in here are atomic particles of the beef from my twenty-first birthday, and the carrot I brought my mother in a bouquet when I was four, and for all I know, the duck served at my parents’ wedding breakfast.’

‘My grandmother did the same thing,’ I told him with a smile. ‘Her pot was always bubbling away – she’d give a bowl to tramps who came to the door, to workmen, to us when we were hungry.’ Which explained why the room’s odour had reminded me of childhood comforts.

‘I could never figure out why it doesn’t taste like the bottom of a dust bin,’ he remarked, sipping from his spoon. ‘Mrs Algernon says it’s because she seasons it with love. I suspect her of using brandy. It is, I have no doubt, massively unhygienic. If we all die in our beds tonight, you will know who is to blame.’

Holmes and I glanced at each other over our unhygienic but satisfying soup, and I could see the same thought in his mind: In removing himself from Palestine, our host had discovered not only a streak of garrulousness, but a sense of mild social humour as well; Ali’s Bedouin humour had tended to involve either bloodshed or heavy burlesque.

Mrs Algernon’s dinner was, as Alistair had said, simple but substantial, if showing signs of a hasty preparation. By the time the pudding course had been cleared, however, the remarkably genial man at the end of the table was fading fast, exhausted by his efforts at sociability. When he attempted to rise, intending to lead the way back into the hall for coffee, he leant hard on the table, then sat down again abruptly. Holmes leapt to his aid while I hurried to fetch Mrs Algernon; we caught up with the two men on the curving stone staircase, Holmes half carrying the younger man upwards. I took Alistair’s other arm, expecting him to throw me off, but he did not.

Mrs Algernon directed us into a wood-panelled chamber with a fire in the grate, a room lifted straight out of a Mediaeval manuscript. We deposited him on a bed not much younger than the house and left him to the scolding ministrations of his housekeeper.